Features

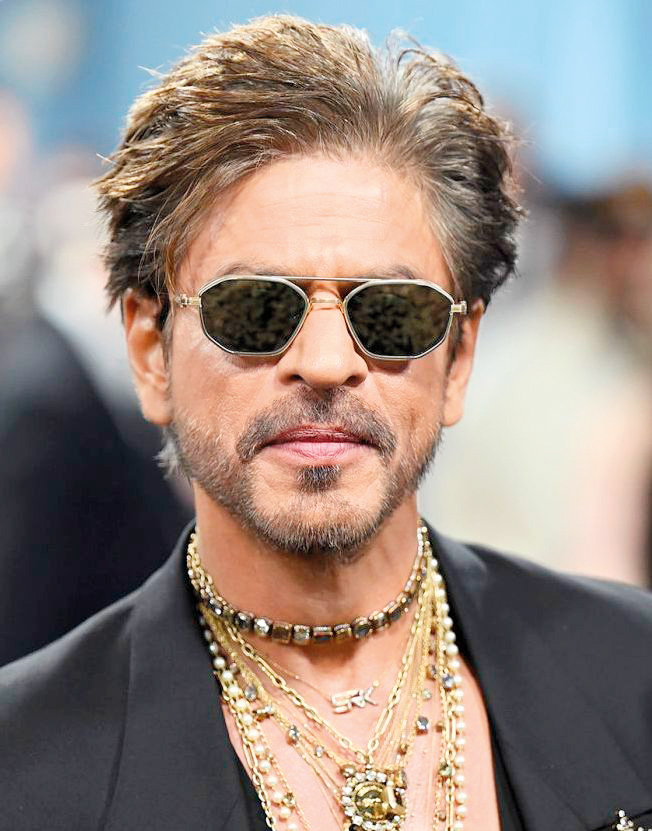

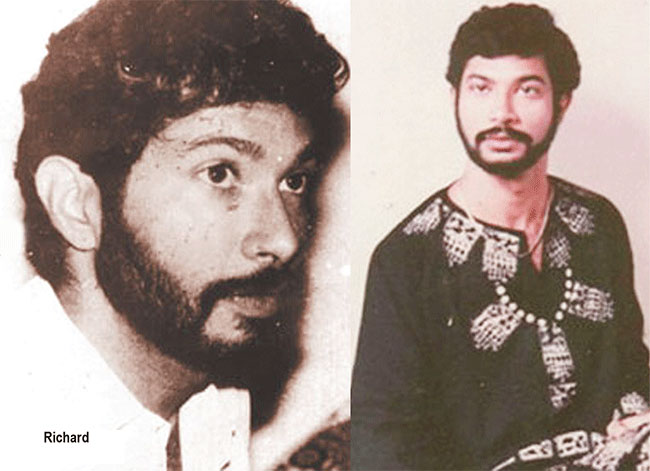

Richard: 32 years later

By Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

It is 32 years today since the body of Richard de Zoysa was washed ashore, after his abduction by government forces. This is a significant date for now he has been dead for longer than he lived. He was just a few weeks short his 32nd birthday when he was killed by government forces. Though this seems an absurd anniversary to think about, I had long thought of it as the time when he would fade further and further into the past, and memory too would begin to die. Thankfully that has not happened and the years of friendship with him are still vivid in my mind.

Richard was the best of companions when I returned from Oxford, and he understood immediately what education should be, at a time when it was being reduced to rote learning. Ashley Halpe still did a great job at Peradeniya but the universities in general were fading, and schools were a mess except where there were exceptional teachers such as at Ladies College. But elsewhere it was rote learning and the taking down of notes, even dictated ones.

I have written extensively about Richard, our friendship, as well as his political development, but today I will confine myself to the programmes we did together, which would never have happened without his enthusiasm and his skill at bringing literature alive. This was contributed from the start, in my first effort to introduce a different approach to literature. That was ‘The Romantic Dilemma’ on the Ladies College stage, illustrating the differences between the older and the younger Romantic poets, read by youngsters whom he brought to me and trained in the nuances we wanted. This was followed by a discussion of different approaches to ‘Romeo and Juliet’ a text at the time, in which we showed how Juliet could be decisive or forlorn, Lady Capulet harsh or helpless, Mercutio lively or despairing.

On my radio programmes,,he read the poetry I talked about, roping in Yolande Abeywira and Jeanne Pinto, older ladies who adored him. We extended such programmes to the British Council when I started working there, and though the first such programme, ‘Flights of Fancy’, presenting a range of poetry about birds, drew only a small audience, it was incredibly well received and attendance grew and grew over the next few months.

He and Yolande went with me to training colleges where we got the students to think about their texts, most interestingly through different approaches to ‘Macbeth’ which was the text at the College at Penideniya. The journeys, too, were great fun, the three of us talking and laughing all the way up and down. We would prepare the different approaches in the car, for I knew I could trust them to get across the nuances I wanted. And they did this even on the day we got carried away and talked, so that it was only through my argument at the College itself that they knew what was wanted.

By the end of 1984, my first year at the British Council, I became more ambitious, inspired after Geraldine McEwan had performed her One-Woman Jane Austen show in November 1984. So early in the following year, I devised a One Man show for Richard, based on some of the novels of Charles Dickens.

Richard was quite magnificient in perfomance, catching the different nuances in six extracts, tragic, comic, pathetic, pompous. I selected music for the different extracts which caught the mood, ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ for Mr Podsnap extolling the virtues of England, sentimental Elgar for the death of Steerforth which was perhaps the most impressive piece in the show. We toured this round the country, including to Batticaloa, and had a marvelous time, looking up old students there.

This was such a success that the following year I put together something based on Kipling, poems and stories. Richard was lyrical in ‘The Way through the Woods’, ridiculous as the butterflies in ‘The Butterfly who Stamped’, rousing in ‘Gunga Din’. That, too, was taken all over the country and we loved the evenings together after the performances were over.

In Galle we stayed at the Sun and Sea Hotel in Unawatuna where Richard and his stage manager Varuna Karunatilleke were joined by Aruni Devaraja and her sister for a lovely holiday, when we explored Madol Doowa of Martin Wickremesinghe fame.

The following year, Richard directed a production of ‘The Merchant of Venice’ with a talented young cast, including Ranmali Pathirana, who now worked with me at the Council, as Portia. I had, however, come back from my round the world trip to find Richard had taken on one of his young protégés and his girlfriend for two minor parts, and they could not act at all. I was highly critical and, though Richard was a bit upset, he replaced them, getting the experienced Kumar Mirchandani to play Lancelot Gobbo, which led to a romance with Ranmali and their getting married.

That too, was great fun, and, in addition to several shows in Colombo, it was performed in Kandy where students of the Penideniya Training College attended, so we could have a discussion on the play there afterwards. And the highlight was taking it to the Pasdunrata College of Education after which David Woolger the Council consultant there, hosted dinner at his house in Wadduwa which had a swimming pool in which the youngsters frolicked.

But then things began to change. Steve de la Zylwa produced ‘Accidental Death of an Anarchist’ in the Council Hall and I recall Richard reflecting that Shakespeare was comparatively precious, given the trauma the country was undergoing. He felt he should have been more in touch with new socio-political trends and sometimes I feel that that contributed to his increasing politicisation in the next couple of years.

When the following year I went to his father’s house at Hendala for his 30th birthday, I met his latest find, a boy called Dahanayake, through whom and indeed more his brother Richard got involved with the JVP.

And then I saw less of him, for he was getting more involved in politics, the story of which he was to tell me in some detail at the end of 1989, when he spent several nights at home under worrying circumstances. He had been led to this through the students he spent more and more time with, Dahanayake, whom he had met through the elder brother I saw at Hendala, and Madura.

The latter was an enormously talented actor and dominated the production Scott Richards put on after a workshop which brought these boys together with the more sophisticated youngsters who had been the staple of such workshops, including Richard’s Josephians from an earlier incarnation. I was very impressed by these new finds, and when Richard asked if one of them, Prasanna Liyanage, could work for me as a CAT in the Cultural Affairs Trainee programme I had started with Mrinali Thalgodapitiya – I agreed at once.

He was very good and when his stint was over I asked Richard if Madura would like to take over. But Richard told me that, after much thought, Madura had refused, on the grounds that entering into that world would cut him off from his roots.

It was a forceful decision, for a boy still in his teens, to take. Richard had explained to me, how these scholarship boys had felt alienated at Royal, which was still dominated by an elite, with not much effort made to integrate them and ensure that both groups benefited from the strengths of the other – something I had tried to do with the Advanced Senior Secondary English Teaching (ASSET) course I had started at the time.

Madura and a couple of the others went on to deep involvement with the JVP, and when Madura was abducted, never to be heard of again, the net began to close on Richard as well. What was happening became clear after his last performance at the Council, when he called after he had left to ask if I had noticed a strange man in the audience. It was his tail, he said, and he wanted to spend the night at home for safety, which he did twice more in the next couple of weeks.

But I will not dwell here on what happened afterwards. Instead, as befits this celebration, I will talk about that last performance, which we put on to celebrate Robert Browning on the centenary of his death. Though by then he was out of fashion, I felt he was a wonderful writer, and was delighted that Regi Siriwardena thought the same and was willing to talk about him. But we told him to be brief, and the bulk of the programme was readings by Richard of the poetry.

It was a glorious performance, capturing the excitement of ‘How they brought the good news from Ghent to Aix’ with its galloping anapaests, lugubrious in ‘Bishop Blougram’s Apology’ which I told him to model on our good friend Suresh Thambipillai, chilling in ‘My Last Duchess’. At the end Lakshmi de Silva, who had been at the first performance we had put on together at the Council, said to me fervently that it was the type of evening that made her glad to be alive.

I was not here when, two months later, he was abducted and killed. That is a small blessing for I remember not that horror but rather the ebullience of his stage presence, which he replicated also in our long conversations. My sister once said she wished she could eavesdrop when she heard me laughing uproariously when I was talking to him on the phone. That is what remains, joy rather than sadness, the exuberance of a commitment to life.

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

Features

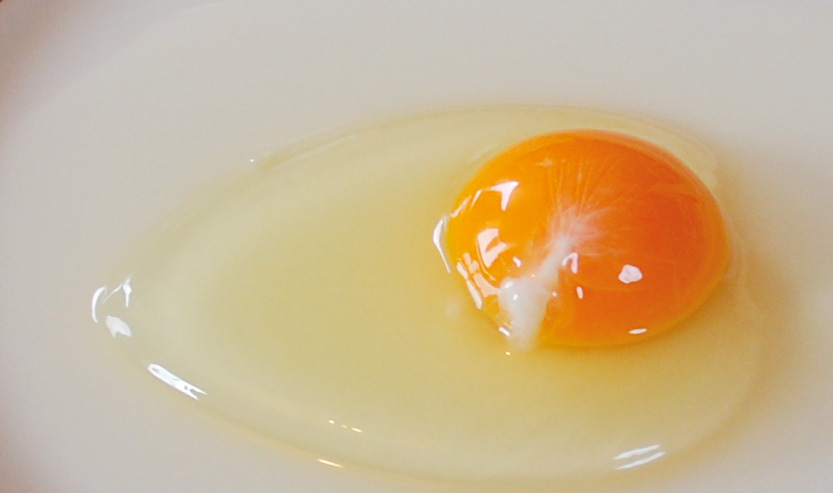

Egg white scene …

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Thought of starting this week with egg white.

Yes, eggs are brimming with nutrients beneficial for your overall health and wellness, but did you know that eggs, especially the whites, are excellent for your complexion?

OK, if you have no idea about how to use egg whites for your face, read on.

Egg White, Lemon, Honey:

Separate the yolk from the egg white and add about a teaspoon of freshly squeezed lemon juice and about one and a half teaspoons of organic honey. Whisk all the ingredients together until they are mixed well.

Apply this mixture to your face and allow it to rest for about 15 minutes before cleansing your face with a gentle face wash.

Don’t forget to apply your favourite moisturiser, after using this face mask, to help seal in all the goodness.

Egg White, Avocado:

In a clean mixing bowl, start by mashing the avocado, until it turns into a soft, lump-free paste, and then add the whites of one egg, a teaspoon of yoghurt and mix everything together until it looks like a creamy paste.

Apply this mixture all over your face and neck area, and leave it on for about 20 to 30 minutes before washing it off with cold water and a gentle face wash.

Egg White, Cucumber, Yoghurt:

In a bowl, add one egg white, one teaspoon each of yoghurt, fresh cucumber juice and organic honey. Mix all the ingredients together until it forms a thick paste.

Apply this paste all over your face and neck area and leave it on for at least 20 minutes and then gently rinse off this face mask with lukewarm water and immediately follow it up with a gentle and nourishing moisturiser.

Egg White, Aloe Vera, Castor Oil:

To the egg white, add about a teaspoon each of aloe vera gel and castor oil and then mix all the ingredients together and apply it all over your face and neck area in a thin, even layer.

Leave it on for about 20 minutes and wash it off with a gentle face wash and some cold water. Follow it up with your favourite moisturiser.

Features

Confusion cropping up with Ne-Yo in the spotlight

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

At an official press conference, held at a five-star venue, in Colombo, it was indicated that the gathering marked a defining moment for Sri Lanka’s entertainment industry as international R&B powerhouse and three-time Grammy Award winner Ne-Yo prepares to take the stage in Colombo this December.

What’s more, the occasion was graced by the presence of Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs of Sri Lanka, and Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe, Deputy Minister of Tourism, alongside distinguished dignitaries, sponsors, and members of the media.

According to reports, the concert had received the official endorsement of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau, recognising it as a flagship initiative in developing the country’s concert economy by attracting fans, and media, from all over South Asia.

However, I had that strange feeling that this concert would not become a reality, keeping in mind what happened to Nick Carter’s Colombo concert – cancelled at the very last moment.

Carter issued a video message announcing he had to return to the USA due to “unforeseen circumstances” and a “family emergency”.

Though “unforeseen circumstances” was the official reason provided by Carter and the local organisers, there was speculation that low ticket sales may also have been a factor in the cancellation.

Well, “Unforeseen Circumstances” has cropped up again!

In a brief statement, via social media, the organisers of the Ne-Yo concert said the decision was taken due to “unforeseen circumstances and factors beyond their control.”

Ne-Yo, too, subsequently made an announcement, citing “Unforeseen circumstances.”

The public has a right to know what these “unforeseen circumstances” are, and who is to be blamed – the organisers or Ne-Yo!

Ne-Yo’s management certainly need to come out with the truth.

However, those who are aware of some of the happenings in the setup here put it down to poor ticket sales, mentioning that the tickets for the concert, and a meet-and-greet event, were exorbitantly high, considering that Ne-Yo is not a current mega star.

We also had a cancellation coming our way from Shah Rukh Khan, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka for the City of Dreams resort launch, and then this was received: “Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal reasons beyond his control, Mr. Khan is no longer able to attend.”

Referring to this kind of mess up, a leading showbiz personality said that it will only make people reluctant to buy their tickets, online.

“Tickets will go mostly at the gate and it will be very bad for the industry,” he added.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRethinking post-disaster urban planning: Lessons from Peradeniya

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAre we reading the sky wrong?