Features

Reviewing Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy

By Neville ladduwahetty

I t is reported that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has tasked the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute (LKI) “with reviewing Sri Lanka’s foreign policy and making recommendations on the structure of the island’s diplomatic apparatus” (The Sunday Morning, October 30, 2022). According to the Executive Director Dr. D. L. Mendis of the LKI, “once the consultations are completed, recommendations on a new foreign policy will be presented to the President and later to Parliament (Ibid). Continuing, Dr. Mendis stated: “Sri Lanka comes first. But we have to also be mindful of our neighbourhood. As a result, our relations should be a bit better with countries in the region, especially India. The Indians also expect us to take that into consideration. The recent Yuan Wang 5 vessel visit is an example.” (Ibid).

The report cited above was followed soon after by a report in the Daily News of October 31, citing the full text of a speech delivered by the Prime Minister, Dinesh Gunawardena at the Convocation of the Bandaranaike International Diplomatic Training Institute (BIDTI). The text of PM’s speech states: “Sri Lanka’s foreign policy is based on neutrality in international affairs and we extend a hand of friendship to every country. But this neutrality should not be taken as a weakness. It is merely a detached neutrality in regional or international power games. Though neutral, we will not allow anybody to use our soil against a third country. In such attempts we zealously safeguard our sovereignty”. The policy of “Neutrality” adopted by Sri Lanka and stated by the PM would in no uncertain terms serve Sri Lanka’s interests better in the background of increasing Great Power Rivalries in and around Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean with the formation of the strategic security alliance of the United States, India, Japan and Australia known as the Quad on the one hand, and China on the other. The fact that the policy of “Neutrality” is backed by the codified provisions in the “Hague Convention (V) Respecting the Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers and Persons in Case of War on Land”, entered into force January 26, 1910 would add strength to “zealously safeguard” Sri Lanka’s sovereignty as evidenced by the Articles of the Convention cited below. The Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers Article 1.

The territory of neutral Powers is inviolable. Art. 2. Belligerents are forbidden to move troops or convoys of either munitions of war or supplies across the territory of a neutral Power. Art. 3. Belligerents are likewise forbidden to: (a) Erect on the territory of a neutral Power a wireless telegraphy station or other apparatus for the purpose of communicating with belligerent forces on land or sea; (b) Use any installation of this kind established by them before the war on the territory of a neutral Power for purely military purposes, and which has not been opened for the service of public messages. Art. 4. Corps of combatants cannot be formed nor recruiting agencies opened on the territory of a neutral Power to assist the belligerents. Art. 5. A neutral Power must not allow any of the acts referred to in Articles 2 to 4 to occur on its territory. It is not called upon to punish acts in violation of its neutrality unless the said acts have been committed on its own territory. Art. 6. The responsibility of a neutral Power is not engaged by the fact of persons crossing the frontier separately to offer their services to one of the belligerents. Art. 7. A neutral Power is not called upon to prevent the export or transport, on behalf of one or other of the belligerents, of arms, munitions of war, or, in general, of anything which can be of use to an army or a fleet. Art. 8. A neutral Power is not called upon to forbid or restrict the use on behalf of the belligerents of telegraph or telephone cables or of wireless telegraphy apparatus belonging to it or to companies or private individuals. Art. 9. Every measure of restriction or prohibition taken by a neutral Power in regard to the matters referred to in Articles 7 and 8 must be impartially applied by it to both belligerents. A neutral Power must see to the same obligation being observed by companies or private individuals owning telegraph or telephone cables or wireless telegraphy apparatus. Art. 10. The fact of a neutral Power resisting, even by force, attempts to violate its neutrality cannot be regarded as a hostile act. In the context of today’s technological advances some of the provisions in the Articles cited above have lost their relevance.

Despite this, sufficient provisions exist to justify any country that adopts a policy of Neutrality to “zealously” protect its sovereignty and territorial integrity. Neutrality in relation to India If the foreign policy of Sri Lanka is Neutral, its conduct in its relations with other countries has to reflect its core value of impartiality. This means Sri Lanka cannot afford to have special relations with some to the exclusivity of others. For instance, the common perception in Sri Lanka is that both geography and history of Sri Lanka and India are so closely knit together that its relations with India must necessarily be different to that with any other State. However, this perception that is founded on history and geography is based on an India that was so vastly different to what India is today. The past relations and bonds that Sri Lanka developed was with an India that consisted of several princely States.

While some of them had a profound influence in molding the culture and heritage of Sri Lanka, with the “gift” of Buddhism from one of these States to Sri Lanka, other States in the South of the subcontinent repeatedly plundered, vandalized and laid waste what was cherished by Sri Lanka. The India that the world sees today was crafted under British Colonial Rule when the entire Indian subcontinent was unified and eventually partitioned at an unimaginable human cost in the process of granting independence to India and Pakistan. It is in such a context that Sri Lanka has to fashion its policy of Neutrality, and not on a past that does not exist today. While Sri Lanka’s security and territorial integrity in the past was dependent on the ambitions of Empires in the Indian subcontinent, by a quirk of fate and circumstance, the security and territorial integrity of today’s India depends on the security and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka. For instance, IF the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka were to separate from the rest of Sri Lanka, as attempted by the LTTE, the support of Tamil Nadu that was given so willingly on grounds of common kinship would have contributed immeasurably towards furthering Tamil Nadu’s own separatist ambitions; a process that would encourage other Southern States to eventually follow suit, with serious consequences on India’s existing territorial integrity, without which its aspiration to be recognized as a global power would have been dented.

It was to prevent such an outcome that India undertook a military mission to defeat the LTTE. Having failed, much to its embarrassment, all India could do was to come up instead with devolution of power to the Provinces in Sri Lanka under the 13th Amendment; a position from which India would not budge because of the unintended consequences that could follow. The common belief is that the choice of Province as the unit of devolution had more to do with appeasing Tamil Nadu instead of devolution to Districts that would have assured Sri Lanka’s territorial integrity and through it assured India’s territorial integrity too. The lesson to be learnt is that both India and Sri Lanka have to adopt policies that assure each other’s territorial integrity because it is in each other’s own self-interests to do so.

Viewed from the perspective presented above it is in India’s selfinterest to help Sri Lanka overcome its current debt crisis. Whatever contribution India has made towards this effort is to ensure that Sri Lanka gets over this crisis, because if Sri Lanka fails, other global powers are bound to exploit the situation at a serious cost to India’s self-interests. This means that any help extended to Sri Lanka is in the pursuit of India’s own self-interest. The important review process that the LKI is tasked to engage in, should develop a fresh perspective in respect of relations with India that is in keeping with current global developments, instead of being influenced by a past that has ceased to exist. Such a perspective should acknowledge that India’s aspirations to become a global power depends on its territorial integrity being intact.

This means axiomatically, that India makes sure that Sri Lanka’s territorial integrity stays intact too. This endeavour should make the relationship between India and Sri Lanka as equal partners engaged in the joint task of ensuring each other’s territorial integrity and not as a big brother or sister of Sri Lanka as believed by some. Sri Lanka’s policy of Neutrality must underscore this sense of reality. Practice of a neutral foreign policy How does a policy of Neutrality manifest itself in practice? First, it means a country that adopts a policy of Neutrality “extend a hand friendship to every country” as stated by the PM at the BIDTI Convocation. Second, such a country cannot be partial to any country over any other or others. Thirdly it must promote and live by the rule of law. This means, a Neutral country cannot pick and choose countries to parcel out infrastructure projects, as for instance to hand over the East Container Terminal to India and Japan and consider offering the West Container Terminal to The Adani Group of India along with a Solar Power Project in Mannar and/or Trincomalee.

Another instance on similar lines was to offer the Hambantota Harbour first to the United States, then to India and finally to China. The practice instead, should be for Sri Lanka to prepare relevant project proposals and call for Expressions of Interest for evaluation and selecting the offer that best suits Sri Lanka’s interests. This means unsolicited proposals have no place in the scheme of a Neutral country. The tendency of Sri Lanka to be influenced by the security concerns of India should have rational and meaningful limits. For instance, objecting to the award of a solar power project to a Chinese Company on the basis of Asian Development Bank procedures by India on grounds of security, should not have been entertained if Sri Lanka is to assert its independence, because no concrete reasons had been presented for India’s objections similar to the decision taken in regard to Yuan Wang 5 of China. As a Neutral State, Sri Lanka has every right to comply with the provisions relating to the “Rights and Duties of a Neutral State” cited above when it comes to addressing requests from other countries.

The exercise of a Neutral policy in a manner that is credible means the ability to act independently. To exercise that independence, Sri Lanka has to be economically independent. Such economic independence comes with food and energy security. Sri Lanka has to focus on these two areas if its Neutrality is not to be compromised. Conclusion The statement by the Prime Minister Dinesh Gunawardena on the occasion of the Convocation of Bandaranaike International Diplomatic Training Institute that “Sri Lanka’s foreign policy is based on Neutrality, is bold and courageous because he has dared to charter a new direction from the long held policy of Non-Alignment.

He has done right by Sri Lanka to recognize the altered geopolitical architecture and adopted a policy to guide Sri Lanka’s relations with the rest of the world in a manner that enables Sri Lanka to accommodate the rivalries developing in an around Sri Lanka made intense by the strategic location destined on the People of Sri Lanka. Unlike the specificity of the policy of Neutrality, the lack of specificity of the former policy of NonAlignment was perhaps the reason for the directionless and lackadaisical performance of the Foreign Ministry and its “diplomatic apparatus” that caused its performance to depend entirely on the leadership given by the Foreign Minister in how Sri Lanka conducted its foreign relations. This was most evident in Sri Lanka’s performance in Geneva. This new beginning means a new direction as to how Sri Lanka and its governments conduct themselves in a manner that makes the policy of neutrality alive as far as its relations with the rest of the world are concerned. If the policy of Neutrality is practiced as recommended above, there is a strong possibility that Sri Lanka would emerge from the crisis that is affecting all the countries without exception, with minimum cost to its image and its dignity.

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

Features

Egg white scene …

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

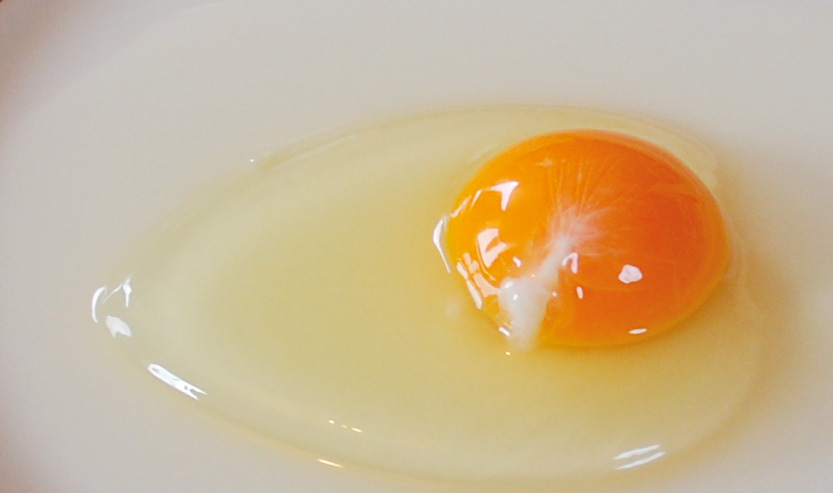

Thought of starting this week with egg white.

Yes, eggs are brimming with nutrients beneficial for your overall health and wellness, but did you know that eggs, especially the whites, are excellent for your complexion?

OK, if you have no idea about how to use egg whites for your face, read on.

Egg White, Lemon, Honey:

Separate the yolk from the egg white and add about a teaspoon of freshly squeezed lemon juice and about one and a half teaspoons of organic honey. Whisk all the ingredients together until they are mixed well.

Apply this mixture to your face and allow it to rest for about 15 minutes before cleansing your face with a gentle face wash.

Don’t forget to apply your favourite moisturiser, after using this face mask, to help seal in all the goodness.

Egg White, Avocado:

In a clean mixing bowl, start by mashing the avocado, until it turns into a soft, lump-free paste, and then add the whites of one egg, a teaspoon of yoghurt and mix everything together until it looks like a creamy paste.

Apply this mixture all over your face and neck area, and leave it on for about 20 to 30 minutes before washing it off with cold water and a gentle face wash.

Egg White, Cucumber, Yoghurt:

In a bowl, add one egg white, one teaspoon each of yoghurt, fresh cucumber juice and organic honey. Mix all the ingredients together until it forms a thick paste.

Apply this paste all over your face and neck area and leave it on for at least 20 minutes and then gently rinse off this face mask with lukewarm water and immediately follow it up with a gentle and nourishing moisturiser.

Egg White, Aloe Vera, Castor Oil:

To the egg white, add about a teaspoon each of aloe vera gel and castor oil and then mix all the ingredients together and apply it all over your face and neck area in a thin, even layer.

Leave it on for about 20 minutes and wash it off with a gentle face wash and some cold water. Follow it up with your favourite moisturiser.

Features

Confusion cropping up with Ne-Yo in the spotlight

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

At an official press conference, held at a five-star venue, in Colombo, it was indicated that the gathering marked a defining moment for Sri Lanka’s entertainment industry as international R&B powerhouse and three-time Grammy Award winner Ne-Yo prepares to take the stage in Colombo this December.

What’s more, the occasion was graced by the presence of Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs of Sri Lanka, and Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe, Deputy Minister of Tourism, alongside distinguished dignitaries, sponsors, and members of the media.

According to reports, the concert had received the official endorsement of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau, recognising it as a flagship initiative in developing the country’s concert economy by attracting fans, and media, from all over South Asia.

However, I had that strange feeling that this concert would not become a reality, keeping in mind what happened to Nick Carter’s Colombo concert – cancelled at the very last moment.

Carter issued a video message announcing he had to return to the USA due to “unforeseen circumstances” and a “family emergency”.

Though “unforeseen circumstances” was the official reason provided by Carter and the local organisers, there was speculation that low ticket sales may also have been a factor in the cancellation.

Well, “Unforeseen Circumstances” has cropped up again!

In a brief statement, via social media, the organisers of the Ne-Yo concert said the decision was taken due to “unforeseen circumstances and factors beyond their control.”

Ne-Yo, too, subsequently made an announcement, citing “Unforeseen circumstances.”

The public has a right to know what these “unforeseen circumstances” are, and who is to be blamed – the organisers or Ne-Yo!

Ne-Yo’s management certainly need to come out with the truth.

However, those who are aware of some of the happenings in the setup here put it down to poor ticket sales, mentioning that the tickets for the concert, and a meet-and-greet event, were exorbitantly high, considering that Ne-Yo is not a current mega star.

We also had a cancellation coming our way from Shah Rukh Khan, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka for the City of Dreams resort launch, and then this was received: “Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal reasons beyond his control, Mr. Khan is no longer able to attend.”

Referring to this kind of mess up, a leading showbiz personality said that it will only make people reluctant to buy their tickets, online.

“Tickets will go mostly at the gate and it will be very bad for the industry,” he added.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRethinking post-disaster urban planning: Lessons from Peradeniya

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAre we reading the sky wrong?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo