Features

Proposed Amendment to Antiquities Ordinance – a boost to destruction of antiquities

By Kalyananda Tiranagama

Executive Director

Lawyers for Human Rights and Development

It has been reported that the Ministry of Justice is moving to amend the Antiquities Ordinance, repealing the provisions therein preventing the courts from releasing persons charged with or accused of offences under the Antiquities Ordinance on bail. Under the proposed amendment, the Magistrate’s Court is to be given power to release such persons on bail. This proposal is made in the guise of a measure to reduce prison congestion.

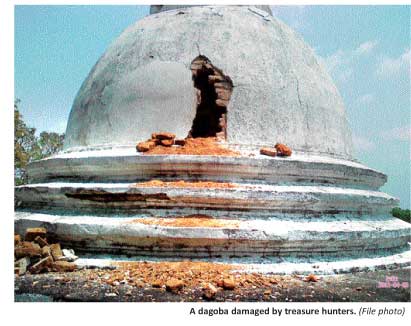

Theft of antiquities, demolition of the Buddha statues and causing damage to archeological sites by treasure hunters and the willful destruction and damage of antiquities and archeological sites by interested parties have become serious problems that need to be urgently addressed with deterrent action.

As reported in the media, from 1977 to 1994 the Police received 242 complaints of theft, damage and destruction of antiquities; from 1995 to 2001, the number of complaints the Police received was 424. There is a sharp increase in the number of incidents reported in the recent past. In 2019, the Archaeological Department received 630 complaints of incidents where antiquities were either damaged or destroyed. During the first nine months of 2020, 430 such incidents were reported to the Archeological Department.

The Antiquities (Amendment) Act No. 24 of 1998 was enacted by Parliament with a view to preventing the incidents of theft of antiquities and willful destruction and damage of antiquities and archeological sites. This Act introduced three new provisions enhancing the penalties for offences under the Ordinance and requiring the offenders to be kept in custody without bail till the conclusion of the trial.

S.15A. Any person committing theft of an antiquity in the possession of any other person shall be guilty of an offence –

S.15B. Any person willfully destroying, injuring, defacing or tampering with an antiquity or willfully damaging any part of it shall be guilty of an offence –

S. 32. Any person who commits a breach of (a) any provision of S. 21 (commencing or carrying out any work of restoration, repair, alteration or addition in connection with any protected monument except upon a permit issued by the Commissioner General of Archeology), or (b) any regulation made under S. 24 shall be guilty of an offence – punishable on conviction after summary trial before a Magistrate with a fine not exceeding Rs. 50,000 or with imprisonment for a term not less than two years and not more than 5 years or with both such fine and imprisonment. Same penalty has been laid down for all offences under the Act.

S. 15C. Notwithstanding anything to the contrary in the Code of Criminal Procedure Act or any other written law, no person charged with or accused of an offence under the Antiquities Ordinance shall be released on bail.

The penalties laid down in the Act for these serious offences are hardly adequate to have a deterrent effect on the culprits. The Court has the option of imposing a fine instead of a jail sentence. The maximum fine that can be imposed is Rs. 50,000. Quite often a fine of a lower amount is imposed. It is very seldom that a sentence of imprisonment is imposed on an offender in these cases.

Only the provision that a person charged with or accused of an offence under the Antiquities Ordinance cannot be released on bail by any Court has some deterrent effect on the offenders. They have to remain in custody for a few weeks or a few months till they are charged in the case. Once they are charged, in most cases they plead guilty and pay a fine and walk away.

In response to certain media reviews critical of this move to amend the law enabling Magistrates to release the suspects on bail when they are produced in Court as something detrimental to the protection of our archeological heritage, Chief Legal Advisor to the Ministry of Justice, Mr. U. R. de Silva, P. C. has issued an explanation justifying the Justice Ministry decision to relax the law, enabling the Magistrates to release the offenders on bail. According to his explanation:

a.

All those who are arrested and produced in Court by the Police are not treasure hunters. Abusing the law, the Police arrest and charge innocent people. As an example, he cites how the Police produce drug addicts in Courts as drug traffickers, preventing them from being released on bail by the Magistrates.

It is no secret that the Police have heavily contributed to the congestion in prisons by producing in Courts many drug addicts as drug traffickers, abusing the law and thus preventing them from being released on bail by the Magistrates. The Attorney General is also aware of this. That is why the Attorney General, following the Mahara Prison riot, stated that he had instructed the Inspector General of Police several times to consider filing cases under S. 78(5) of the Poisons, Opium and Dangerous Drugs (Amendment) Act instead of S. 54 (a), which has been the usual practice, in order to reduce prison congestion.

Why doesn’t the Ministry of Justice propose to amend the Poisons, Opium and Dangerous Drugs Act, enabling Magistrates to grant bail to persons arrested with small quantities of drugs instead of keeping them in custody for years without bail, in the same manner it proposes to amend the Antiquities Ordinance?

If the Police abuse the law by arresting and producing in Courts innocent people as treasure hunters and keep them in custody without bail, why can’t the AG and the IGP direct them to strictly comply with the law and take action against the police officers who abuse the law?

b.

This is a state of affairs totally different from what the legislature expected.

It is an erroneous statement. Parliament enacted this law in 1998 specifically for the purpose of protecting antiquities by taking stern action against those who damage or destroy them. S. 15C clearly states that whatever the other laws may state, no person charged with or accused of an offence under the Antiquities Ordinance shall be released on bail.

c.

As the Immigrants and Emigrants Act has been amended enabling Courts to release suspects on bail, it is a grave mistake not to amend the Antiquities Ordinance enabling Courts to grant bail.

This is also not a correct statement. The Immigrants and Emigrants Act was amended by Act No. 31 of 2006 to grant relief to hundreds of suspects held in custody being unable to obtain bail due to the Supreme Court Judgment given in 2006 in Thilanga Sumathipala case (Attorney General & others vs. Thilanga Sumathipala – (2006) 2 SLR 126) depriving the Court of Appeal of its jurisdiction to grant bail.

This Act made provision for release on bail of all persons held in remand without bail on the date on which this Act came into operation due to the Supreme Court Judgment in the Thilanga Sumathipala case.

This Amendment Act did not grant power to the Magistrate’s Courts to release on bail all suspects held in custody in respect of all offences under the Immigrants and Emigrants Act. Under this Amendment, a Magistrate can grant bail only for an offence in respect of which there is no express provision made for granting bail. – S. 47A (2) Where there is an express provision for granting bail, a Magistrate cannot grant bail in respect of such offences.

Only a High Court can grant bail to a person accused of an offence under S. 45C of the Act upon proof of exceptional circumstances.

S. 47 (1) of the Act states that, notwithstanding anything in any other law, the offences mentioned therein shall be non-bailable and no person accused of such an offence shall in any circumstances be admitted to bail.

d.

Whenever any digging is done anywhere the Police have the habit of arresting persons and producing them in Court as suspects under the Antiquities Ordinance. They have to languish in custody for months till the certificate is produced showing that it is not a place coming under the Antiquities Ordinance.

The Antiquities Ordinance clearly states what are the offences coming under it. Instead of amending the law enabling Magistrates to release the offenders committing all kinds offences under the Ordinance on bail at the time they are produced in Court, there are many things that can be done to prevent the Police from acting arbitrarily abusing the law.

The Police cannot arbitrarily arrest people and produce them in Court for digging any land; If they do so a complaint can be made against the Police to the Supreme Court or the Human Rights Commission for violation of fundamental rights.

The Attorney General can direct the Police not to arrest and prosecute without ascertaining from the Archeological Department whether it is a site with antiquities.

The Court can promptly call for the certificate from the Archeological Department.

e. Another sorry state of affairs is that, though the place where the digging was done is not a place coming under the Antiquities Ordinance, the Police file action on the opinion of the Commissioner General of Archaeology that charges can be brought if it appears that the digging has been done in search of antiquities.

No such action can be filed under the law. It is an arbitrary action taken totally contrary to law. One cannot understand why the Bar Association of Sri Lanka and the lawyers appearing in these cases remain silent without challenging the legality of such actions.

f. As they cannot obtain bail, in many of these cases suspects plead guilty for an offence which they have not committed and pay the fine of Rs. 50,000 getting their image tarnished. Having understood this practical reality, the Ministry of Justice has taken action to address this issue.

This is a strange story. Why should a person plead guilty for an offence which he has not committed? How can a lawyer advise his client to plead guilty to an offence which he has never committed?

What are these cases in which the innocent people have pleaded guilty for offences which they have never committed and paid fines of Rs. 50,000 tarnishing their images? Before which Courts? Can the Ministry of Justice issue a list of these cases?

Why should they pay Rs. 50,000 in each of these cases? Rs. 50,000 is the maximum fine a Court can impose for any of these offences. As laid down in the Act, the penalty is a fine not exceeding Rs. 50,000. The Court has the discretion to impose a lesser fine. Depending on the circumstances of the case it may be a fine of Rs. 10,000, 20,000 or 25,000.

All these are false premises.

Archeological sites and antiquities in a country are the national historical heritage of the people of the country. Not only the present generation, but all the future generations also have an equal right to them. Destruction of archeological sites and antiquities will result in the destruction of the historical national heritage of the people of the country. It may be a deliberate attempt at turning the history of the country upside down by erasing historical evidence. It is worse than any act of destruction of environment.

If any forest is destroyed it can re-forested. But if an antiquity or an archeological site is destroyed it can never be restored to its previous condition. Bamian Buddha Statues destroyed by Talaiban in Afghanistan is a clear example. A replica may be erected in its place, but it has no historical or archeological value. Any change, alteration, removal or addition of parts in an antiquity or an archeological site will result in the diminution of its archeological value. That is why even commencing or carrying out any work of restoration, repair, alteration or addition in connection with any protected monument without a permit issued by the Commissioner General of Archeology has been made an offence punishable under the law and all offences under the Antiquities Ordinance have been made unbailable by any Court of law.

Frequently our media, both print and electronic, disclose incidents of destruction of antiquities and archeological sites throughout the country. Many of these incidents reported from the Northern and Eastern Provinces, are not acts of treasure hunters, but deliberate and planned acts of destruction of archeological sites by interested parties. Though hundreds of such incidents are reported, very seldom legal action is taken against the culprits due to lack of adequate resources in the Archeological Department and lethargy or insensitivity of the officials.

In the face of the threats currently posed, antiquities and archeological sites remain survived even to this extent due to the provision in S. 15C of the Ordinance that no person charged with or accused of an offence under the Antiquities Ordinance shall be released on bail by any Court. Even the Court of Appeal has no jurisdiction to release such a person on bail. If the Antiquities Ordinance is amended as proposed by the Ministry of Justice granting jurisdiction to Magistrate’s Courts to release on bail offenders charged with offences under the Antiquities Ordinance, any offender who has deliberately destroyed any priceless antiquity or archeological site will be able to obtain bail and go home on the day he was produced in Court itself. This will amount to giving an open license for the destruction of archeological heritage of our people. As the maximum fine that can be imposed is Rs. 50,000, any offender can pay the fine and get the license. By paying the fine he can get away after destroying any antiquity.

The Chief Legal Advisor to the Ministry of Justice has suggested to increase the penalties for the offence while granting jurisdiction to Magistrate’s Courts to release offenders on bail. If the offenders can get bail from the Magistrate’s Court when they are produced in Court, even if the amount of fine that can be imposed for the offence is increased to Rs. 500,000, that will not have any deterrent effect in preventing deliberate and planned activities of destruction of archeological sites in the North – East and other areas in the country.

If this amendment proposed by the Ministry of Justice is brought about that will seal the fate of all our unprotected antiquities and archeological sites. It will wide open the gates for destruction of our invaluable antiquities and archeological sites.as happened in the case of Devanagala, Kuragala and Vijithapura. No museum, antiquity or archeological site will remain safe thereafter.

It is an unshirkable duty and responsibility of the Government to protect this national heritage of our people for the posterity. It can be done not by relaxation of the laws enacted for the purpose protecting them, but by further strengthening the law against this destruction. If a mandatory minimum jail sentence coupled with a fine, such as imprisonment for a term not less than two years and not more than 5 years and a fine not less than Rs. 50,000, is laid down for the offences of theft of an antiquity and willfully destroying, injuring, damaging, defacing or tampering with an antiquity then the penalty may have a deterrent effect on persons prone to commit this type of offences. Persons committing these anti-national crimes must be kept in custody without bail till the conclusion of the trial as in the case of offences under the Prevention of Terrorism Act.

Features

Lasting solutions require consensus

Problems and solutions in plural societies like Sri Lanka’s which have deep rooted ethnic, religious and linguistic cleavages require a consciously inclusive approach. A major challenge for any government in Sri Lanka is to correctly identify the problems faced by different groups with strong identities and find solutions to them. The durability of democratic systems in divided societies depends less on electoral victories than on institutionalised inclusion, consultation, and negotiated compromise. When problems are defined only through the lens of a single political formation, even one that enjoys a large electoral mandate, such as obtained by the NPP government, the policy prescriptions derived from that diagnosis will likely overlook the experiences of communities that may remain outside the ruling party. The result could end up being resistance to those policies, uneven implementation and eventual political backlash.

A recent survey done by the National Peace Council (NPC), in Jaffna, in the North, at a focus group discussion for young people on citizen perception in the electoral process, revealed interesting developments. The results of the NPC micro survey support the findings of the national survey by Verite Research that found that government approval rating stood at 65 percent in early February 2026. A majority of the respondents in Jaffna affirm that they feel safer and more fairly treated than in the past. There is a clear improving trend to be seen in some areas, but not in all. This survey of predominantly young and educated respondents shows 78 percent saying livelihood has improved and an equal percentage feeling safe in daily life. 75 percent express satisfaction with the new government and 64 percent believe the state treats their language and culture fairly. These are not insignificant gains in a region that bore the brunt of three decades of war.

Yet the same survey reveals deep reservations that temper this optimism. Only 25 percent are satisfied with the handling of past issues. An equal percentage see no change in land and military related concerns. Most strikingly, almost 90 percent are worried about land being taken without consent for religious purposes. A significant number are uncertain whether the future will be better. These negative sentiments cannot be brushed aside as marginal. They point to unresolved structural questions relating to land rights, demilitarisation, accountability and the locus of political power. If these issues are not addressed sooner rather than later, the current stability may prove fragile. This suggests the need to build consensus with other parties to ensure long-term stability and legitimacy, and the need for partnership to address national issues.

NPP Absence

National or local level problems solving is unlikely to be successful in the longer term if it only proceeds from the thinking of one group of people even if they are the most enlightened. Problem solving requires the engagement of those from different ethno-religious, caste and political backgrounds to get a diversity of ideas and possible solutions. It does not mean getting corrupted or having to give up the good for the worse. It means testing ideas in the public sphere. Legitimacy flows not merely from winning elections but from the quality of public reasoning that precedes decision-making. The experience of successful post-conflict societies shows that long term peace and development are built through dialogue platforms where civil society organisations, political actors, business communities, and local representatives jointly define problems before negotiating policy responses.

As a civil society organisation, the National Peace Council engages in a variety of public activities that focus on awareness and relationship building across communities. Participants in those activities include community leaders, religious clergy, local level government officials and grassroots political party representatives. However, along with other civil society organisations, NPC has been finding it difficult to get the participation of members of the NPP at those events. The excuse given for the absence of ruling party members is that they are too busy as they are involved in a plenitude of activities. The question is whether the ruling party members have too much on their plate or whether it is due to a reluctance to work with others.

The general belief is that those from the ruling party need to get special permission from the party hierarchy for activities organised by groups not under their control. The reluctance of the ruling party to permit its members to join the activities of other organisations may be the concern that they will get ideas that are different from those held by the party leadership. The concern may be that these different ideas will either corrupt the ruling party members or cause dissent within the ranks of the ruling party. But lasting reform in a plural society requires precisely this exposure. If 90 percent of surveyed youth in Jaffna are worried about land issues, then engaging them, rather than shielding party representatives from uncomfortable conversations, is essential for accurate problem identification.

North Star

The Leader of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), Prof Tissa Vitarana, who passed away last week, gave the example for national level problem solving. As a government minister he took on the challenge the protracted ethnic conflict that led to three decades of war. He set his mind on the solution and engaged with all but never veered from his conviction about what the solution would be. This was the North Star to him, said his son to me at his funeral, the direction to which the Compass (Malimawa) pointed at all times. Prof Vitarana held the view that in a diverse and plural society there was a need to devolve power and share power in a structured way between the majority community and minority communities. His example illustrates that engagement does not require ideological capitulation. It requires clarity of purpose combined with openness to dialogue.

The ethnic and religious peace that prevails today owes much to the efforts of people like Prof Vitarana and other like-minded persons and groups which, for many years, engaged as underdogs with those who were more powerful. The commitment to equality of citizenship, non-racism, non-extremism and non-discrimination, upheld by the present government, comes from this foundation. But the NPC survey suggests that symbolic recognition and improved daily safety are not enough. Respondents prioritise personal safety, truth regarding missing persons, return of land, language use and reduction of military involvement. They are also asking for jobs after graduation, local economic opportunity, protection of property rights, and tangible improvements that allow them to remain in Jaffna rather than migrate.

If solutions are to be lasting they cannot be unilaterally imposed by one party on the others. Lasting solutions cannot be unilateral solutions. They must emerge from a shared diagnosis of the country’s deepest problems and from a willingness to address the negative sentiments that persist beneath the surface of cautious optimism. Only then can progress be secured against reversal and anchored in the consent of the wider polity. Engaging with the opposition can help mitigate the hyper-confrontational and divisive political culture of the past. This means that the ruling party needs to consider not only how to protect its existing members by cloistering them from those who think differently but also expand its vision and membership by convincing others to join them in problem solving at multiple levels. This requires engagement and not avoidance or withdrawal.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Unpacking public responses to educational reforms

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

Two broad reactions

The reactions to the proposed reforms can be broadly categorised into ‘pro’ and ‘anti’. I will discuss the latter first. Most of the backlash against the reforms seems to be directed at the issue of a gay dating site, accidentally being linked to the Grade 6 English module. While the importance of rigour cannot be overstated in such a process, the sheer volume of the energies concentrated on this is also indicative of how hopelessly homophobic our society is, especially its educators, including those in trade unions. These dispositions are a crucial part of the reason why educational reforms are needed in the first place. If only there was a fraction of the interest in ‘keeping up with the rest of the world’ in terms of IT, skills, and so on, in this area as well!

Then there is the opposition mounted by teachers’ trade unions and others about the process of the reforms not being very democratic, which I (and many others in higher education, as evidenced by a recent statement, available at https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/ ) fully agree with. But I earnestly hope the conversation is not usurped by those wanting to promote heteronormativity, further entrenching bigotry only education itself can save us from. With this important qualification, I, too, believe the government should open up the reform process to the public, rather than just ‘informing’ them of it.

It is unclear both as to why the process had to be behind closed doors, as well as why the government seems to be in a hurry to push the reforms through. Considering other recent developments, like the continued extension of emergency rule, tabling of the Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), and proposing a new Authority for the protection of the Central Highlands (as is famously known, Authorities directly come under the Executive, and, therefore, further strengthen the Presidency; a reasonable question would be as to why the existing apparatus cannot be strengthened for this purpose), this appears especially suspect.

Further, according to the Secretary to the MOE Nalaka Kaluwewa: “The full framework for the [education] reforms was already in place [when the Dissanayake government took office]” (https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2025/08/12/wxua-a12.html, citing The Morning, July 29). Given the ideological inclinations of the former Wickremesinghe government and the IMF negotiations taking place at the time, the continuation of education reforms, initiated in such a context with very little modification, leaves little doubt as to their intent: to facilitate the churning out of cheap labour for the global market (with very little cushioning from external shocks and reproducing global inequalities), while raising enough revenue in the process to service debt.

This process privileges STEM subjects, which are “considered to contribute to higher levels of ‘employability’ among their graduates … With their emphasis on transferable skills and demonstrable competency levels, STEM subjects provide tools that are well suited for the abstraction of labour required by capitalism, particularly at the global level where comparability across a wide array of labour markets matters more than ever before” (my own previous piece in this column on 29 October 2024). Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) subjects are deprioritised as a result. However, the wisdom of an education policy that is solely focused on responding to the global market has been questioned in this column and elsewhere, both because the global market has no reason to prioritise our needs as well as because such an orientation comes at the cost of a strategy for improving the conditions within Sri Lanka, in all sectors. This is why we need a more emancipatory vision for education geared towards building a fairer society domestically where the fruits of prosperity are enjoyed by all.

The second broad reaction to the reforms is to earnestly embrace them. The reasons behind this need to be taken seriously, although it echoes the mantra of the global market. According to one parent participating in a protest against the halting of the reform process: “The world is moving forward with new inventions and technology, but here in Sri Lanka, our children are still burdened with outdated methods. Opposition politicians send their children to international schools or abroad, while ours depend on free education. Stopping these reforms is the lowest act I’ve seen as a mother” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). While it is worth mentioning that it is not only the opposition, nor in fact only politicians, who send their children to international schools and abroad, the point holds. Updating the curriculum to reflect the changing needs of a society will invariably strengthen the case for free education. However, as mentioned before, if not combined with a vision for harnessing education’s emancipatory potential for the country, such a move would simply translate into one of integrating Sri Lanka to the world market to produce cheap labour for the colonial and neocolonial masters.

According to another parent in a similar protest: “Our children were excited about lighter schoolbags and a better future. Now they are left in despair” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). Again, a valid concern, but one that seems to be completely buying into the rhetoric of the government. As many pieces in this column have already shown, even though the structure of assessments will shift from exam-heavy to more interim forms of assessment (which is very welcome), the number of modules/subjects will actually increase, pushing a greater, not lesser, workload on students.

A file photo of a satyagraha against education reforms

What kind of education?

The ‘pro’ reactions outlined above stem from valid concerns, and, therefore, need to be taken seriously. Relatedly, we have to keep in mind that opening the process up to public engagement will not necessarily result in some of the outcomes, those particularly in the HSS academic community, would like to see, such as increasing the HSS component in the syllabus, changing weightages assigned to such subjects, reintroducing them to the basket of mandatory subjects, etc., because of the increasing traction of STEM subjects as a surer way to lock in a good future income.

Academics do have a role to play here, though: 1) actively engage with various groups of people to understand their rationales behind supporting or opposing the reforms; 2) reflect on how such preferences are constituted, and what they in turn contribute towards constituting (including the global and local patterns of accumulation and structures of oppression they perpetuate); 3) bring these reflections back into further conversations, enabling a mutually conditioning exchange; 4) collectively work out a plan for reforming education based on the above, preferably in an arrangement that directly informs policy. A reform process informed by such a dialectical exchange, and a system of education based on the results of these reflections, will have greater substantive value while also responding to the changing times.

Two important prerequisites for this kind of endeavour to succeed are that first, academics participate, irrespective of whether they publicly endorsed this government or not, and second, that the government responds with humility and accountability, without denial and shifting the blame on to individuals. While we cannot help the second, we can start with the first.

Conclusion

For a government that came into power riding the wave of ‘system change’, it is perhaps more important than for any other government that these reforms are done for the right reasons, not to mention following the right methods (of consultation and deliberation). For instance, developing soft skills or incorporating vocational education to the curriculum could be done either in a way that reproduces Sri Lanka’s marginality in the global economic order (which is ‘system preservation’), or lays the groundwork to develop a workforce first and foremost for the country, limited as this approach may be. An inextricable concern is what is denoted by ‘the country’ here: a few affluent groups, a majority ethno-religious category, or everyone living here? How we define ‘the country’ will centrally influence how education policy (among others) will be formulated, just as much as the quality of education influences how we – students, teachers, parents, policymakers, bureaucrats, ‘experts’ – think about such categories. That is precisely why more thought should go to education policymaking than perhaps any other sector.

(Hasini Lecamwasam is attached to the Department of Political Science, University of Peradeniya).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

Features

Chef’s daughter cooking up a storm…

Don Sherman was quite a popular figure in the entertainment scene but now he is better known as the Singing Chef and that’s because he turns out some yummy dishes at his restaurant, in Rajagiriya.

Don Sherman was quite a popular figure in the entertainment scene but now he is better known as the Singing Chef and that’s because he turns out some yummy dishes at his restaurant, in Rajagiriya.

However, now the spotlight is gradually focusing on his daughter Emma Shanaya who has turned out to be a very talented singer.

In fact, we have spotlighted her in The Island a couple of times and she is in the limelight, once gain.

When Emma released her debut music video, titled ‘You Made Me Feel,’ the feedback was very encouraging and at that point in time she said “I only want to keep doing bigger and greater things and ‘You Made Me Feel’ is the very first step to a long journey.”

Emma, who resides in Melbourne, Australia, is in Sri Lanka, at the moment, and has released her very first Sinhala single.

“I’m back in Sri Lanka with a brand new single and this time it’s a Sinhalese song … yes, my debut Sinhala song ‘Sanasum Mawana’ (Bloom like a Flower).

“This song is very special to me as I wrote the lyrics in English and then got it translated and re-written by my mother, and my amazing and very talented producer Thilina Boralessa. Thilina also composed the music, and mix and master of the track.”

Emma went on to say that instead of a love song, or a young romance, she wanted to give the Sri Lankan audience a debut song with some meaning and substance that will portray her, not only as an artiste, but as the person she is.

Says Emma: “‘Sanasum Mawana’ is about life, love and the essence of a woman. This song is for the special woman in your life, whether it be your mother, sister, friend, daughter or partner. I personally dedicate this song to my mother. I wouldn’t be where I am right now if it weren’t for her.”

On Friday, 30th January, ‘Sanasum Mawana’ went live on YouTube and all streaming platforms, and just before it went live, she went on to say, they had a wonderful and intimate launch event at her father’s institute/ restaurant, the ‘Don Sherman Institute’ in Rajagiriya.

It was an evening of celebration, good food and great vibes and the event was also an introduction to Emma Shanaya the person and artiste.

Emma also mentioned that she is Sri Lanka for an extended period – a “work holiday”.

“I would like to expand my creativity in Sri Lanka and see the opportunities the island has in store for me. I look forward to singing, modelling, and acting opportunities, and to work with some wonderful people.

“Thank you to everyone that is by my side, supporting me on this new and exciting journey. I can’t wait to bring you more and continue to bloom like a flower.”

-

Life style3 days ago

Life style3 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Midweek Review7 days ago

Midweek Review7 days agoA question of national pride

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka: