Features

Probably most brilliant officer the Army ever had

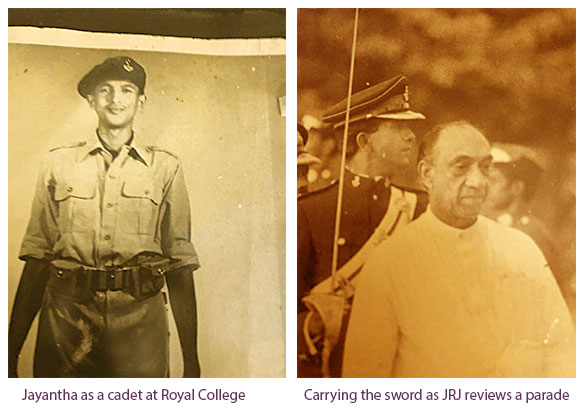

Lt Col PVJ (Jayantha) de Silva, SL Light Infantry (1941-2023):

Maj. Gen. (Retd.) Lalin Fernando

“Do not stand at my grave and cry; I am not there; I did not die”

Late Lt Col PVJ (Jayantha) de Silva, Sri Lanka Light Infantry, (the oldest regiment in the Army – raised in 1881), served in the SL Army from 1964 to 1987.He sadly passed away in Australia after a fall just short of his 80th birthday.

He was probably the most brilliant officer the Army ever had; some say even a genius. He was also an unwavering, staunch, stubborn patriot as he was unforgiving of those, military or political who faltered. I admired him. He was my very good friend.

Educated at Royal College where he was prefect and Cadet Sergeant, he was also a national basketball player. He was in the first intake of five officer cadets to the Pakistan Military Academy in Kakul in 1964. He, showing extraordinary leadership potential to prove himself among Pakistani cadets from the famed martial races of Punjabis, Pathans and Baluchis being appointed Battalion Junior Under Officer in his final term. He was the first and only one from Ceylon (SL) to be so appointed on the regular long course of two and a half years (It is now a two-year course).

He came third (of over 200 cadets) in the order of merit. The others in the Ceylon intake of five included Srilal Weerasuriya, later General and Army Commander. He later graduated from the Indian Staff College, Wellington, being recommended for Operations and Training, the plum posting for the best achievers. He was excellent in the field and on the staff.

I came across some of his Light Infantry soldiers in Talaimannar on a search operation when on Anti Illicit Immigration duties in the late 1960s. They spoke with pride of their lean, six-foot-tall whipcord strong, platoon commander’s successes. Clearly, he had looked after their every need as indeed the regimental motto “Ich Dien” (I serve) expected him to do – to serve his men. Many senior officers in a politicized army do not understand the motto believing ‘I serve’ means serve politicians!

Jayantha’s extraordinary feats were many and legendary. When the Russians gifted 82 mm mortars after the 1971 JVP Insurgency, Jayantha was the leader of the army infantry team of officers and sergeants chosen to be instructed on the weapon. The Russians took the whole of the first day to introduce the new weapon in the belief that the locals had to learn from scratch probably unaware we were well trained on the British three-inch mortars albeit of WW 2 origin.

At the end of the first day Jayantha asked the bemused Russians to take the next day off. He asked the infantry team to assemble at the Panaluwa range the next morning. The team was taught everything about the weapon including how to fire it by Jayantha. The following morning the Russians were taken to the firing range instead of the weapon training area. The sections of the team then demonstrated the dismantling and assembling of the mortar.

The Russians were next taken to the field firing range where the mortar bombs (shells) were fired. The planned six-week course was over! That was PVJ.

When his SLLI commanding officer Lt Col (later Major General) HV (Henry) Athukorale wanted a regimental museum, he created one almost overnight. He was entrusted with revising the Regimental Standing Orders. When Military Assistant (MA) to the Commander of the Army, Lt Gen Denis Perera, he produced the most comprehensive Army Dress Regulations. All in quick time.

I remember Jayantha as the first ever MA to an Army Commander (Maj Gen Denis Perera) accompanying the Commander on the first of the Army Commander’s bi-annual Inspection team at HQ Task Force One at Pallaly (Jaffna). In the evening at the Officers’ Mess the mood was convivial with the gift of two bottles of whiskey from the Commander helping; but Jayantha was missing.

The next morning as the Commander and his staff left for the airport the Minutes of the inspection, accurate and critical with action to be taken, would be in my hands. This speed of response upset some commanding officers (who complained). They were used to ambling along previously. Now their command deficiencies were pinpointed. The Army was in a resurgent era.

At the Non-Aligned Conference held in Colombo, about 100 heads of state or government, attended. They had each to be given a Guard of Honour at Katunayake whatever time they arrived. Their arrivals were within a short intervals of each other. Jayantha was Deputy to Brig TI Weeratunge (later Army Commander). Brig Weeratunge had time on his hands as Jayantha had organized rehearsals, timings and dress inspections with passion. The ceremonials were outstanding.

The VVIPs arriving included Mrs. Indira Gandhi, Sadat, Makarios (Cyprus), Hafiz al Assad and the eccentric Libyan leader Gaddafi. Marshal Tito arrived in his yacht in the Colombo harbour.

As Commandant of the Combat Training School in Ampara he revamped it entirely. Everything from theory lessons, conduct of field tactical exercises and Standard Operating Procedures were in writing. His successors had only to follow them.

While SL was laboring to match the terrorists early lead in technology, it was to Jayantha that the Army Commander turned to build SL’s first indigenous Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) with a V shaped hull. It proved to be far superior against mines to the imported, much acclaimed South African APC. He did so with a team of technicians from the Electrical and Mechanical Engineers at their Colombo workshop. And he was just an infantry officer.

Had Jayantha remained in the Army instead of emigrating, he would have worked wonders with technology but he had no far thinking Gen Sundarji (brilliant Indian Chief of Army Staff and the only infantry officer to command the First Indian Armoured Division too) or any brass hat to back him in an unsophisticated army given to sycophancy and later even commanded by one who gifted weapons and ammo to the terrorists.

He could have given the Army a lead in AI too. Instead, his inputs were apparently in the Australian Defence Industry. He was last heard providing (unsolicited?) detailed inputs for Australia’s indigenous aircraft carrier. While Sundarji wrote “Blind Men of Hindustan” as his treatise on Indian Nuclear Policy was not too well received, Jayantha wrote a new Constitution for SL that he insisted I read to know how to resolve our problems. I was tactful in responding.

Jayantha had a Kodak camera with which he recorded many events in camp and on training. I requested him to photograph my wedding and gave him a roll of film. He gave me a whole lot of super wedding photos and returned the film as he was wont to do. When years later he found his camera outdated, he searched for the newfangled parts needed to upgrade it. He could not find any. Jayantha then manufactured them and soon had a camera that was uptodate.

He then sent the drawings of his work to many camera companies. Only Kodak responded. They asked whether he had registered for copyrights. He said no. Kodak asked whether they could come to an agreement about producing the parts. He told them there was no need for an agreement and they could just have it. They asked whether they could use his name. He said it was unnecessary as both knew who did the work!

I first met Jayantha when he was an officer cadet in 1964.I was on a Regimental Signals Officer’s course at Rawalpindi. He would come with four other cadets including Srilal Weerasuriya (later General and Commander of the Army) and stay in my officers’ mess quarters during the rare training breaks. They would each bring their bed rolls and lay it out in the sitting room so they had no problem about sleeping.

They also joined four officers (Capts Kamal Fernando and WM Weerasuriya, Lt SJ Weerasena and me to form a ‘Ceylon Army’ cricket team to play GHQ Pakistan. The five cadets were not very impressive cricketers. We were loaned two Pakistani officers who were not any better. We lost. They had a national player who had just played against the MCC. He scored a century.

The next time we met was in mid-1968 was when we were both appointed Instructors for the first ever Officer Cadets course held in SL at the Officer Cadet School (now the SL Military Academy) at the Army Training Center (ATC) Diyatalawa. We replaced the two instructors who had been there during the first term. This was a most rewarding posting ever as we were in charge of not just new officer cadets but of the promise of the army’s future. This intake, initially of 12, was incomparable.

We were very fortunate that Lt Col (later General and Commander of the Army from the first Ceylon Intake at Sandhurst Denis Perera was first the Deputy (to Col Lyn Wicramasuriya) and then Commandant of the ATC. He ensured that the cadets wanted in nothing. Maj MD Fernando was the Chief Instructor (CI).

We soon discovered that instructor sergeants and sergeant major whose duties were respectively drill and weapons, had been allowed to impose themselves on the cadets in their free time and in the cadets’ mess. A hurried meeting on the first day itself laid down the ground rules. The other rank instructors were told that the accommodation and cadets mess were not in their province and to desist from going there as everything there was the responsibility of Officer instructors alone.

This was a clean break from what had been going on when directly enlisted officers were trained and NCOs ran the roost after close of the days play. Warrant Officer Ahmath (Armoured Corps) was an excellent Wing Sergeant Major.

The cadets had been told to start digging a well at the top of the hill overlooking the Halangode Wewa! This was stopped on the first day itself. The foundation, standards, customs and traditions were set initially by the officer instructors. They were handed down inviolate by Intake One who by the time Intake Two and a volunteer force intake of young officers arrived, had matured enough to govern and set the pattern for the succeeding intakes. The term Beast Billet (for first termers) came into vogue then. Bullying and ragging were not allowed as Intake One had set the standard.

The first three intakes had the founder commander of the Commandos and two Army Commanders including SL’s only Field Marshal and a rifle shooting Olympian who twice contested!

Field training exercises were talked about long after they ended. The first initiative exercise was held in the Passara hills with planters being ‘friendly collaborators’ of ‘cadet saboteurs’, then in Ampara in a tropical thunderstorm at night that made the cadets think the exercise would be called off. It wasn’t. The two instructors accompanied each ‘sabotage’ patrol across flooded paddies and raging torrents near the airport. The third was in Trincomalee.

Conventional warfare exercises were held on Fox Hill, in Gurutalawa and Horton Plains. Jungle training was carried out in the South Eastern jungles off Kuda Oya by the British Far East Jungle Warfare School Malaya-trained Capt (later Major General) Wijaya Wimalaratne and Warrant Officer Jayasinghe, both from Gemunu Watch.

On parade Warrant Officer Dayananda, (Armoured Corps) trained at the Brigade of Guards Drill Depot Pirbright, UK) never failed to say after each rehearsal for the Commissioning parade that every officer must try to match Jayantha’s sword drill standard – that included the parade commander- me!

The rugby team with a galaxy of schoolboy players in Intake Three won the Clifford Cup C Division the first time it entered.

Jayantha had the very best leadership characteristics starting from unshakable integrity, physical and moral courage, in depth knowledge of his profession including its technical side, initiative, was lightning fast in taking decisions and implementing them. He was fair and just in all his dealings. He was straight, unafraid to speak his mind but not haughty or arrogant, pleasant mannered and adaptive, lean and hard, highly motivated and disciplined. He never spoke of race or religion in the best traditions of the Army. He was first class at everything he had to do in the Army except for playing cricket. He was a true friend and loyal.

He had little patience, never gossiped, was firm, hardly merciful, was uncompromising and not very flexible. When asked by a retired Army commander visiting Australia why he did not want to meet him (the former commander), he said simply ‘You saluted the terrorists’ (during the 2001-3 phony Norwegian sponsored peace initiative).

The question must then be asked why an outstanding mid ranking officer whose early promise blossomed throughout his career abruptly decided to quit the army and migrate to Australia as a Lt Col, when achieving the highest command rank was a probability. Clearly in SL it was not. I cannot think of any army other than SL’s where such an exceptional officer would have been allowed to go without an effort to retain him. Was there an exit interview? I doubt it as at that time the army had lost a lot of its confidence and a few army commanders had openly said the war could not be won, shamelessly contradicting their own appointments.

One had secretly followed treacherous orders and arranged weapons and ammo plus cash in dollars and cement to be given to the LTTE on the treasonable orders of a Commander-in Chief!

As for career planning it appeared that was in the hands of politicians. Shocking debacles followed. Thousands died. No senior commander was punished. Many were promoted. Sadly, it appeared that the deaths of thousands of soldiers and young officers mattered less than the need to protect the guilty Generals.

A guilty conscience pervaded the upper ranks. They did not in many cases serve their men. By 2006 the lessons were well learned, the surviving fighting elements had been to hell and back for decades They were ready to finish it off. They did so with a political leadership that for once made sure the Army and the forces in general lacked nothing to win the conflict.

Jayantha had not been given command of his battalion despite being the most outstanding mid ranking officer not only in his regiment but also in the army to deserve it. When asked, two former Army Commanders, one his intake mate to the Pakistan Military Academy and the other who he had trained, thought it was due to the fact that Jayantha’s last two bosses as Army Commanders (1981-88) made prolific use of his amazing grasp of technology for the army rather than release him to command his regiment, the vital starting point of higher command. This could have happened only in the SL Army as any career plan had to give command of one’s own regiment the highest priority.

It is probable that in many other armies a similar talent would have seen the incumbent given a double promotion straight to Brigadier. All this was not to be. In my humble opinion, had Jayantha stayed on he would have made the best and most effective and successful Army commander albeit in his time, after Gen Denis Perera.

On a personal note, I remember going with my family to Kandy for the Perahera. Jayantha who was the senior staff officer in Central, Command made all the arrangements for our stay. At night he saw that only my elder daughter and I were going out as my wife would stay with our two-year old second daughter. He immediately said he would look after the baby and asked for instructions. On our return about midnight, we saw Jayantha with a pen light torch reading a book having prepared and given the baby her milk on time. In his spare time Jayantha coached the Trinity College basketball team.

When Jayantha left SL, the Army lost her most talented officer, his friends lost a wonderful and close friend. His death in Australia came as a shock to all. The saddest part was that we in SL were sure he would outlive all of us even as most of us had not seen him for nearly 35 years; but he never forgot SL, the Army and us and kept our morale up during the darkest days of the conflict with his unrelenting confidence in final victory.

He will be much missed by all who knew him. May his stay in Samsara be short. He leaves his wife Chintha, daughter Piyumali and son Suresh.

Note

Intake one had the head prefects of Royal, S Thomas’, Kingswood and St John’s, Jaffna, the cricket captain of Ananda and Combined Schools, national rifle firing pool member (and twice future Olympian), three public school athletes, a Nalanda cricketer, vice-captain Royal College rugby, one Royal College rowing team member and a soldier entry who was a national rugby player.

Features

Crucial test for religious and ethnic harmony in Bangladesh

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

The apprehensions are mainly on the part of religious and ethnic minorities. The parliamentary poll of February 12th is expected to bring into existence a government headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Islamist oriented Jamaat-e-Islami party and this is where the rub is. If these parties win, will it be a case of Bangladesh sliding in the direction of a theocracy or a state where majoritarian chauvinism thrives?

Chief of the Jamaat, Shafiqur Rahman, who was interviewed by sections of the international media recently said that there is no need for minority groups in Bangladesh to have the above fears. He assured, essentially, that the state that will come into being will be equable and inclusive. May it be so, is likely to be the wish of those who cherish a tension-free Bangladesh.

The party that could have posed a challenge to the above parties, the Awami League Party of former Prime Minister Hasina Wased, is out of the running on account of a suspension that was imposed on it by the authorities and the mentioned majoritarian-oriented parties are expected to have it easy at the polls.

A positive that has emerged against the backdrop of the poll is that most ordinary people in Bangladesh, be they Muslim or Hindu, are for communal and religious harmony and it is hoped that this sentiment will strongly prevail, going ahead. Interestingly, most of them were of the view, when interviewed, that it was the politicians who sowed the seeds of discord in the country and this viewpoint is widely shared by publics all over the region in respect of the politicians of their countries.

Some sections of the Jamaat party were of the view that matters with regard to the orientation of governance are best left to the incoming parliament to decide on but such opinions will be cold comfort for minority groups. If the parliamentary majority comes to consist of hard line Islamists, for instance, there is nothing to prevent the country from going in for theocratic governance. Consequently, minority group fears over their safety and protection cannot be prevented from spreading.

Therefore, we come back to the question of just and fair governance and whether Bangladesh’s future rulers could ensure these essential conditions of democratic rule. The latter, it is hoped, will be sufficiently perceptive to ascertain that a Bangladesh rife with religious and ethnic tensions, and therefore unstable, would not be in the interests of Bangladesh and those of the region’s countries.

Unfortunately, politicians region-wide fall for the lure of ethnic, religious and linguistic chauvinism. This happens even in the case of politicians who claim to be democratic in orientation. This fate even befell Bangladesh’s Awami League Party, which claims to be democratic and socialist in general outlook.

We have it on the authority of Taslima Nasrin in her ground-breaking novel, ‘Lajja’, that the Awami Party was not of any substantial help to Bangladesh’s Hindus, for example, when violence was unleashed on them by sections of the majority community. In fact some elements in the Awami Party were found to be siding with the Hindus’ murderous persecutors. Such are the temptations of hard line majoritarianism.

In Sri Lanka’s past numerous have been the occasions when even self-professed Leftists and their parties have conveniently fallen in line with Southern nationalist groups with self-interest in mind. The present NPP government in Sri Lanka has been waxing lyrical about fostering national reconciliation and harmony but it is yet to prove its worthiness on this score in practice. The NPP government remains untested material.

As a first step towards national reconciliation it is hoped that Sri Lanka’s present rulers would learn the Tamil language and address the people of the North and East of the country in Tamil and not Sinhala, which most Tamil-speaking people do not understand. We earnestly await official language reforms which afford to Tamil the dignity it deserves.

An acid test awaits Bangladesh as well on the nation-building front. Not only must all forms of chauvinism be shunned by the incoming rulers but a secular, truly democratic Bangladesh awaits being licked into shape. All identity barriers among people need to be abolished and it is this process that is referred to as nation-building.

On the foreign policy frontier, a task of foremost importance for Bangladesh is the need to build bridges of amity with India. If pragmatism is to rule the roost in foreign policy formulation, Bangladesh would place priority to the overcoming of this challenge. The repatriation to Bangladesh of ex-Prime Minister Hasina could emerge as a steep hurdle to bilateral accord but sagacious diplomacy must be used by Bangladesh to get over the problem.

A reply to N.A. de S. Amaratunga

A response has been penned by N.A. de S. Amaratunga (please see p5 of ‘The Island’ of February 6th) to a previous column by me on ‘ India shaping-up as a Swing State’, published in this newspaper on January 29th , but I remain firmly convinced that India remains a foremost democracy and a Swing State in the making.

If the countries of South Asia are to effectively manage ‘murderous terrorism’, particularly of the separatist kind, then they would do well to adopt to the best of their ability a system of government that provides for power decentralization from the centre to the provinces or periphery, as the case may be. This system has stood India in good stead and ought to prove effective in all other states that have fears of disintegration.

Moreover, power decentralization ensures that all communities within a country enjoy some self-governing rights within an overall unitary governance framework. Such power-sharing is a hallmark of democratic governance.

Features

Celebrating Valentine’s Day …

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Merlina Fernando (Singer)

Yes, it’s a special day for lovers all over the world and it’s even more special to me because 14th February is the birthday of my husband Suresh, who’s the lead guitarist of my band Mission.

We have planned to celebrate Valentine’s Day and his Birthday together and it will be a wonderful night as always.

We will be having our fans and close friends, on that night, with their loved ones at Highso – City Max hotel Dubai, from 9.00 pm onwards.

Lorensz Francke (Elvis Tribute Artiste)

On Valentine’s Day I will be performing a live concert at a Wealthy Senior Home for Men and Women, and their families will be attending, as well.

I will be performing live with romantic, iconic love songs and my song list would include ‘Can’t Help falling in Love’, ‘Love Me Tender’, ‘Burning Love’, ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’, ‘The Wonder of You’ and ‘’It’s Now or Never’ to name a few.

To make Valentine’s Day extra special I will give the Home folks red satin scarfs.

Emma Shanaya (Singer)

I plan on spending the day of love with my girls, especially my best friend. I don’t have a romantic Valentine this year but I am thrilled to spend it with the girl that loves me through and through. I’ll be in Colombo and look forward to go to a cute cafe and spend some quality time with my childhood best friend Zulha.

JAYASRI

Emma-and-Maneeka

This Valentine’s Day the band JAYASRI we will be really busy; in the morning we will be landing in Sri Lanka, after our Oman Tour; then in the afternoon we are invited as Chief Guests at our Maris Stella College Sports Meet, Negombo, and late night we will be with LineOne band live in Karandeniya Open Air Down South. Everywhere we will be sharing LOVE with the mass crowds.

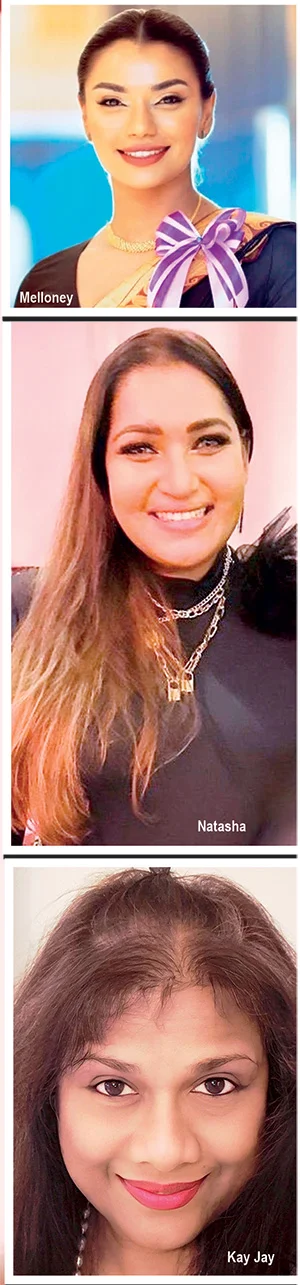

Kay Jay (Singer)

I will stay at home and cook a lovely meal for lunch, watch some movies, together with Sanjaya, and, maybe we go out for dinner and have a lovely time. Come to think of it, every day is Valentine’s Day for me with Sanjaya Alles.

Maneka Liyanage (Beauty Tips)

On this special day, I celebrate love by spending meaningful time with the people I cherish. I prepare food with love and share meals together, because food made with love brings hearts closer. I enjoy my leisure time with them — talking, laughing, sharing stories, understanding each other, and creating beautiful memories. My wish for this Valentine’s Day is a world without fighting — a world where we love one another like our own beloved, where we do not hurt others, even through a single word or action. Let us choose kindness, patience, and understanding in everything we do.

Janaka Palapathwala (Singer)

Janaka

Valentine’s Day should not be the only day we speak about love.

From the moment we are born into this world, we seek love, first through the very drop of our mother’s milk, then through the boundless care of our Mother and Father, and the embrace of family.

Love is everywhere. All living beings, even plants, respond in affection when they are loved.

As we grow, we learn to love, and to be loved. One day, that love inspires us to build a new family of our own.

Love has no beginning and no end. It flows through every stage of life, timeless, endless, and eternal.

Natasha Rathnayake (Singer)

We don’t have any special plans for Valentine’s Day. When you’ve been in love with the same person for over 25 years, you realise that love isn’t a performance reserved for one calendar date. My husband and I have never been big on public displays, or grand gestures, on 14th February. Our love is expressed quietly and consistently, in ordinary, uncelebrated moments.

With time, you learn that love isn’t about proving anything to the world or buying into a commercialised idea of romance—flowers that wilt, sweets that spike blood sugar, and gifts that impress briefly but add little real value. In today’s society, marketing often pushes the idea that love is proven by how much money you spend, and that buying things is treated as a sign of commitment.

Real love doesn’t need reminders or price tags. It lives in showing up every day, choosing each other on unromantic days, and nurturing the relationship intentionally and without an audience.

This isn’t a judgment on those who enjoy celebrating Valentine’s Day. It’s simply a personal choice.

Melloney Dassanayake (Miss Universe Sri Lanka 2024)

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I’m incredibly blessed because, for me, every day feels like Valentine’s Day. My special person makes sure of that through the smallest gestures, the quiet moments, and the simple reminders that love lives in the details. He shows me that it’s the little things that count, and that love doesn’t need grand stages to feel extraordinary. This Valentine’s Day, perfection would be something intimate and meaningful: a cozy picnic in our home garden, surrounded by nature, laughter, and warmth, followed by an abstract drawing session where we let our creativity flow freely. To me, that’s what love is – simple, soulful, expressive, and deeply personal. When love is real, every ordinary moment becomes magical.

Noshin De Silva (Actress)

Valentine’s Day is one of my favourite holidays! I love the décor, the hearts everywhere, the pinks and reds, heart-shaped chocolates, and roses all around. But honestly, I believe every day can be Valentine’s Day.

It doesn’t have to be just about romantic love. It’s a chance to celebrate love in all its forms with friends, family, or even by taking a little time for yourself.

Whether you’re spending the day with someone special or enjoying your own company, it’s a reminder to appreciate meaningful connections, show kindness, and lead with love every day.

And yes, I’m fully on theme this year with heart nail art and heart mehendi design!

Wishing everyone a very happy Valentine’s Day, but, remember, love yourself first, and don’t forget to treat yourself.

Sending my love to all of you.

Features

Banana and Aloe Vera

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

This nutrient-rich blend acts as an antioxidant-packed anti-ageing treatment that also doubles as a nourishing, shiny hair mask.

* Face Masks for Glowing Skin:

Mix 01 ripe banana with 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel and apply this mixture to the face. Massage for a few minutes, leave for 15-20 minutes, and then rinse off for a glowing complexion.

* Acne and Soothing Mask:

Mix 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel with 1/2 a mashed banana and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply this mixture to clean skin to calm inflammation, reduce redness, and hydrate dry, sensitive skin. Leave for 15-20 minutes, and rinse with warm water.

* Hair Treatment for Shine:

Mix 01 fresh ripe banana with 03 tablespoons of fresh aloe vera gel and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply from scalp to ends, massage for 10-15 minutes and then let it dry for maximum absorption. Rinse thoroughly with cool water for soft, shiny, and frizz-free hair.

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoGREAT 2025–2030: Sri Lanka’s Green ambition meets a grid reality check