Features

Policies call for coordination in power sector

by Neville Ladduwahetty

The material presented below relates to the policies explored by successive governments to meet the rising demands for water and electric power. Consequently, the policies adopted are with the intention of either increasing demands for water and power generation capacities, directly or indirectly, as a byproduct of another policy. They are presented as contradictions herein as the objective achieved by implementing one policy contradicts directly or impacts negatively on the objectives of another policy. For instance, new projects are pursued at considerable cost without expanding existing facilities to meet near identical power generation capabilities. Another instance is that water demands in one region are met at the cost of impacting negatively on existing power generation capacities.

Addressed below are three projects that expand on the above general claims:

1. Calling for bids to build, operate and transfer a new 350MW Liquid Nitrogen Gas (LNG) plant in Kerawalapitiya at a cost to the government’s Renewable Energy Programme.

2. Building new plants without expanding capacities at Victoria and Kotmale.

3. To transfer water to the Northern Province by transferring water from Randenigala to Moragahakanda at a loss of power generation at Randenigala and impacting negatively on the supply of water to the left and right banks of the Mahaweli at Minipe.

350 MW LNG PLANT at KERAWALAPITIYA

The most recent contradiction in the Power Sector is the Framework Agreement signed by the Government of Sri Lanka with New Fortress Energy (NFE), an American energy-based Company on September 17, 2021, to introduce LNG as the source to generate electric power. Since this is a fossil fuel it would be a set-back to the government’s own programme for Renewable Energy.

According to a press release issued by New Fortress Energy on September 21, 2021, and reported by NEW YORK–(BUSINESS WIRE) “The Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (GOSL) jointly announced today that they have executed a definitive agreement for New Fortress’ investment in West Coast Power Limited (WCP), the owner of the 310 MW Yugadanavi Power Plant, based in Colombo, along with the rights to develop a new LNG Terminal off the coast of Colombo, the capital city. As part of the transaction, New Fortress will have gas supply rights to the Kerawalapitiya Power Complex, where 310 MW of power is operational today and an additional 700 MW scheduled to be built, of which 350 MW is scheduled to be operational by 2023”.

This means that as a result of the deal with NFE the total power generating complex at Kerawalapitiya would consist of the existing 310 MW plant, the 350 MW plant expected to be completed in 2023, and another new 350 MW plant to be built latter, thus making a total of 1010 MW of power generation. Furthermore, all these plants would be operating on LNG. In order to make all three plants operational, NFE has retained the right to develop a new LNG Terminal and as reported, with exclusive rights to supply LNG for a period of five years with the provision to renew supplies for a further 10 years.

Leaving aside the merits and demerits of the deal with NFE, there is a need to understand the overall status relating to the power sector. With implementation of the deal with NFE, what Sri Lanka would end up would be a 1010 MW LNG plant at Kerawalapitiya, 900 MW of a coal-fired plant at Norochcholai and a commitment to increase Renewable Energy (RE). Therefore, instead of expanding the capacities at Kerawalapitiya to 1010 MW, the deal with NFE from the perspective of Sri Lanka’s national interests, particularly from an environmental point of view, should be to convert the existing coal-fired plant at Norochcholai to LNG along with the LNG Terminal from Kerawalapitiya to Norochcholai. Such a shift of focus from Kerawalapitiya to Norochcholai would not affect progress on the RE Programme. Furthermore, converting from coal to LNG would significantly improve the quality of the environment in and around Norochcholai.

EXPANDING CAPACITIES AT VICTORIA AND KOTMALE

Another contradiction is the policy of the government to call for bids to set up a new 350 MW LNG plant at Kerawalapitiya without expanding the capacities of existing plants. A glaring example of this is that the recommendations proposed in a “Feasibility Study for Expansion of Victoria Hydropower Station”, dated June 2009, undertaken for the Ministry of Power and Energy on behalf of Japan International corporation Agency (JICA), have not been explored.

Section 6.1 of this report states: “The expansion of the Victoria Hydropower Station is composed of a headrace tunnel, a surge tank, penstock(s) and a powerhouse. The water intake was already constructed for the purpose of future expansion of the hydropower facility during the construction of the existing Victoria dam…One possible option of expansion plan is simply to place these components nearby the existing hydropower facility…referred to as ‘Basic Option’” (p. 29). Although the Report presents two other options, what is recommended is “to place an expansion powerhouse nearby the existing powerhouse facility.”

In the Section under Conclusions and Recommendations, the Report states: “Based on the results in (5) above, the Project is to connect the existing intake for the expansion and a new powerhouse to be located next to the existing powerhouse with a waterway parallel to the existing waterway. Water for generation of 140 m3/s is to be taken at the existing intake for the expansion and led through the headrace tunnel and penstock to the surface type powerhouse. The installed capacity is 228 MW with 2 units, and 716 GWh of annual energy are obtained with the existing and expansion power facilities (210 MW and 228 MW). Power generated is evacuated to the CEB grid through the existing transmission lines” (Ibid, p.4).

The material presented above clearly demonstrates that a real opportunity exists to double the capacity at Victoria using a resource that is not only the cleanest and cheapest resource to generate power but also one that allows these freely available resources to be wasted without making full use of their potential. It is indeed a serious omission to pursue new power generation units such as at Kerawalapitiya without expanding capacities at existing power generation units such as at Victoria.

TRANSFER of WATER to the NORTH

Yet another contradiction is the construction of the Upper Elahera Canal to transfer water from Moragahakanda to the Iranamadu Tank in the Northern Province. To achieve such an objective, it is necessary to transfer a considerable volume of water from Randenigala which is below the Victoria Hydropower Scheme back to Moragahakanda and in the process, to not only lose the power generating capacity at Randenigala but also to drastically affect the current supply of water to the right and left banks of the Mahaweli at Minipe.

There are several Reports addressing this issue of supplying much needed water to the North Central Province (NCP) and the Northern Province (NP). The concept of diverting water from the South to the North are central to a majority of the Reports because their studies have revealed that current arrangements do not have the capacity to deliver water to the NCP and the NP.

For instance, Paragraph 21 (p. 343) of the Report dated December 2014 prepared for the Ministry Irrigation and Water Resources Management by Technical Assistance Consultant on behalf of the ADB states: “The study has shown an increase in the diversion capacity at Moragahakanda to 974 MCM annually, required for the Upper Elahera Canal (UEC) and NCP canals addition to 617 MCM to the Elehera Minneriya Yoda Ela. The supplemental diversions from Kalu Ganga (772 MCM) Bowatenna (496 MCM) reservoirs and its own watershed (344 MCM) are adequate to cater the water demands under UEC.”

The conclusion that “adequate” water exists to deliver 974 MCM to the UEC and through it to the North Central and Northern Provinces depends on the availability of 772 MCM through the Kalu Ganga. Since arrangements to deliver the 772 MCM currently DO NOT exist, what is available is the water diverted from Bowatenna, namely 496 MCM and the 344 MCM in the existing catchments, making a total of 840 MCM minus the 617 MCM needed for the ancient five tanks from the Elahera Yoda Ela.

Therefore, what possibly could be transferred by the Upper Elahera Canal is 223 MCM. This is less than the 281 MCM intended to be transferred to Mannakkattiya-Eruwewa-Mahakandarawa (155 MCM) and 126 MCM to Huruluwewa according to paragraph 151 in the Report titled “Environment Impact Assessment Report” prepared for the Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources Management” by the Mahaweli Consultancy Bureau (Pvt) Ltd. in December 2014.

In an independent study carried out by SMEC International (Pvt) Ltd for the World Bank titled “Updated Mahaweli Water Resources Development Plan”, dated November 2013 states in Appendix 5 Table 5.1, p.9 that the Downstream Release from Bowatenne as 651 MCM, the catchment inflow into Moragahakanda as 313 MCM and the release to the five ancient tanks from the Elahera-Minneriya Yoda Ela as 573 MCM. Therefore, water available for transfer to Upper Elahera Canal is 651+313= 964 MCM less 573 MCM, which is 391 MCM. Thus, the quantity of water in excess of what is needed for Mannakkattiya-Eruwewa-Mahakandarawa (155 MCM) and 126 MCM to Huruluwewa) is 110 MCM. Thus, this report confirms the findings of the previous report that there is insufficient water to meet water demands to the areas beyond Anuradhapura to the NCP and the NP.

The conclusions that could be objectively reached from the analysis of data in both reports is that as long as no arrangements exist to transfer water from Randenigala to Moragahakanda the quantities of water available are NOT sufficient to meet the demands of the NCP and the NP.

The proposal therefore is to transfer water from Randenigala augmented by water from Hasalaka Oya and Heen Ganga along the way together with water in 128 sq. km of the Kalu Ganga catchment (say76 MCM) to meet the demands for water in the NCP and NP. Since the water demands in these two small tanks are 75 and 56 MCM respectively, Randenigala would need to divert 772MCM less (76+75+56) which is 565 MCM annually. Diverting 565 MCM of water from Randenigala, which is equal to the active capacity of the reservoir would have a serious impact not only on power generation but also on the amount of water available for diversion to the right and left banks of the Mahaweli at Minipe. Therefore, diverting water to Moragahakanda from Randenigala is NOT an option. Diverting water to the NCP and NP at the expense of power generation and water availability to the East of Sri Lanka is a clear instance of contradictory policies that have been actively pursued by successive governments.

CONCLUSION

What is evident from a review of the projects cited above is that they are conceived and conceptualized in isolation without taking a holistic view at the planning stage and taking into account the impact of either ongoing projects or projects that are planned to be implemented. The three topics reviewed are, the New Fortress Energy(NFE) proposal to increase the power generation capacity at Kerawalapitiya, not capitalizing the capabilities to nearly double the generating capacity at Victoria and the delivery of water to the North.

For instance, the CEB had called for international bids to install a 350 MW LNG plant at Kerawalapitiya. Prior to the closing of bids, the government entered into a Framework Agreement with NFE to build two 350 MW LNG plants alongside the existing 300 MW plant at Kerawalapitiya together with a Floating Storage Regasification Unit (FSRU) to handle the LNG. The generating capacity at Kerawalapitiya would then be 1010 MW. In the meantime, the existing 900 MW coal fired at Norocholai would continue to belch pollutants associated with coal-fire power units. Therefore, the intended project should be redefined to convert the plant at Norochcholai to LNG and for the FSRU that was to be built at Kaeawalapitiya to be moved to Norochcholai. In addition, the needed increase in power generation should be met by doubling the capacity at Victoria as suggested in a Report to the Ministry of Power and Energy prepared by Japan International Cooperation Agency with any shortcomings being provided by Renewable Energy.

With regard to delivery of water to the North, the data presented above clearly demonstrates that as long as current levels of diversion from Bowatenna continue and water from its own catchments prevail, the quantities of water at Moragahakanda are insufficient to meet the demands in the NCP and NP. The ONLY way water demands of the NCP and NP could be met through the Upper Elahera Canal is by transferring nearly 565 MCM, which is equal to the active capacity of Randenigala Reservoir to Moragahakanda. The impact of transferring such a significant amount of water would not only be to curtail power generation but also to impact seriously on availability of water to fulfill the needs on the right and left banks of the Mahaweli at Minipe. This is a clear example of the policy of Mahaweli water to the North contradicting the policy of power generation and supply of water for agriculture.

These hard realities are known only to a few. Consequently, the expectation that water would eventually reach the North is so real that the general belief is that water to the North from the South is what would unify Sri Lanka. Therefore, it is imperative that measures are adopted to correct these misplaced perceptions and for alternative strategies to be developed to meet the demands for water in the NCP and the NP with the participations of the people concerned.

It is hoped that the material presented above would alert governments and project planners to take a holistic perspective when projects are conceptualized and not take compartmentalized approaches as demonstrated by the few examples cited above.

Features

Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part I

Sri Lanka’s survival and independence have historically depended on accurately identifying foreign policy priorities, selecting viable strategies as a small island state, and advancing them with prudence. This requires an objective assessment of the shifting geopolitical landscape through a distinctly Sri Lankan strategic lens. Consequently, foreign policy has been central to Sri Lanka’s statecraft, warranted by its pivotal location in the Indian Ocean—adjacent to South Asia yet separated by a narrow stretch of water.

Amid pivotal geopolitical transformations in motion across South Asia, in the Indian Ocean, and beyond, the formulation and implementation of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy has never been more critical to its national security. Despite the pressing need for a cohesive policy framework, Sri Lanka’s foreign policy, over the past few decades, has struggled to effectively respond to the challenges posed by shifting geopolitical dynamics. This article examines the evolution of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy and its inconsistencies amid shifting geopolitical dynamics since the end of the Cold War.

First

, the article examines geopolitical shifts in three key spaces—South Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the global arena—since the end of the Cold War, from Sri Lanka’s strategic perspective. Building on this, second, it analyses Sri Lanka’s foreign policy responses, emphasising its role as a key instrument of statecraft. Third, it explores the link between Sri Lanka’s foreign policy dilemmas during this period and the ongoing crisis of the post-colonial state. Finally, the article concludes that while geopolitical constraints persist, Sri Lanka’s ability to adopt a more proactive foreign policy depends on internal political and economic reforms that strengthen democracy and inclusivity.

Shifting South Asian Strategic Dynamics

Geopolitical concerns in South Asia—Sri Lanka’s immediate sphere—take precedence, as the country is inherently tied to the Indo-centric South Asian socio-cultural milieu. Sri Lanka’s foreign policy has long faced challenges in navigating its relationship with India, conditioned by a perceived disparity in power capabilities between the two countries. This dynamic has made the ‘India factor’ a persistent consideration in Sri Lanka’s strategic thinking. As Ivor Jennings observed in 1951, ‘India thus appears as a friendly but potentially dangerous neighbour, to whom one must be polite but a little distant’ (Jennings, 1951, 113).The importance of managing the ‘India Factor’ in Sri Lankan foreign policy has grown further with India’s advancements in military strength, economic development, and the knowledge industry, positioning it as a rising global great power on Sri Lanka’s doorstep.

India’s Strategic Rise

Over the past three decades, South Asia’s geopolitical landscape has undergone a profound transformation, driven by India’s strategic rise as a global great power. Barry Buzan (2002:2) foresees this shift within the South Asian regional system as a transition from asymmetric bipolarity to India-centric unipolarity. India’s continuous military advancements have elevated it to the fourth position in the Global Firepower (GFP) index, highlighting its formidable conventional war-making capabilities across land, sea, and air (Global Firepower, 2024). It currently lays claims to being the world’s third-largest military, the fourth-largest Air Force, and the fifth-largest Navy.

India consistently ranks among the fastest-growing major economies, often surpassing the global average. According to Forbes India, India is projected to be the world’s fifth-largest economy in 2025, with a real GDP growth rate of 6.5% (Forbes, January 10, 2025). India’s strategic ascendance is increasingly driven by its advancements in the knowledge industry. The country is actively embracing the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) and emerging as the Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) hub of South Asia. However, India’s rise has a paradoxical impact on its neighbours. On one hand, it offers them an opportunity to integrate into a rapidly expanding economic engine. On the other, it heightens concerns over India’s dominance, leaving them feeling increasingly overshadowed by the regional giant.

Despite significant geo-strategic transformations, the longstanding antagonism and strategic rivalry between India and Pakistan have persisted into the new millennium, continuing to shape South Asia’s security landscape. Born in 1947 amid mutual hostility, the two countries remained locked in a multi-dimensional conflict encompassing territorial disputes, power equilibrium, threat perceptions, accusations of interference in each other’s domestic affairs, and divergent foreign policy approaches. The acquisition of nuclear weapons by both countries in 1998 added a new dimension to their rivalry.

The SAARC process has been a notable casualty of the enduring Indo-Pakistani rivalry. Since India’s boycott of the Islamabad Summit in response to the 2016 Uri attack in Kashmir, the SAARC process has remained in limbo. Countries like Sri Lanka, which seek to maintain equally amicable relations with both India and Pakistan, often find themselves in awkward positions due to the ongoing rivalry between them. One of the key challenges for Sri Lanka’s foreign policy is maintaining strong relations with Pakistan while ensuring its ties with India remain unaffected. India now actively promotes regional cooperation bodies in South Asia, excluding Pakistan, favouring broader frameworks such as BIMSTEC. While Sri Lanka can benefit greatly from engaging with these regional initiatives, it must carefully navigate its involvement to avoid inadvertently aligning with India’s efforts to contain Pakistan. Maintaining this balance will require sharp diplomatic acumen.

India’s expansive naval strategy, especially its development of onshore naval infrastructure, has positioned Sri Lanka within its maritime sphere of influence. As part of the Maritime Infrastructure Perspective Plan (MIPP) launched in 2015 to enhance operational readiness and surveillance capabilities, India is developing an alternative nuclear submarine base for the Eastern Command under Project Varsha (Deccan Chronicle, 22.11.2016). This base is located in Rambilli village, 50 km southwest of Visakhapatnam and 1,200 km from Colombo (Chang, 2024). Additionally, INS Dega, the naval air base at Visakhapatnam, is being expanded to accommodate Vikrant’s MiG-29K and Tejas fighter aircraft.

Another key strategic development in India’s ascent that warrants serious attention in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy formulation is India’s progress in missile delivery systems (ICBMs and SLBMs) and nuclear-powered submarines. In 1998, India made it clear that its future nuclear deterrence would be based on a nuclear triad consisting of land-based Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and strategic bombers (Rehman, 2015). Since then, India has steadily advanced in this direction. The expansion of India’s missile delivery systems, including ICBMs and SLBMs, serves as a reminder that Sri Lanka exists under the strategic shadow of a major global power.

The development of India’s nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) accelerated after 2016. The first in this class, INS Arihant (S2), was commissioned in August 2016, followed by the launch of INS Arighat in November 2021. Designed for strategic deterrence, INS Arighat is equipped to carry the Sagarika K-4 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), with a range of 3,500 kilometers, as well as the K-5, a long-range SLBM capable of reaching 5,000 kilometers. The submarine is based at INS Varsha (Deb, 2021).

India has significantly advanced its missile delivery systems, improving both their range and precision. In 2021, it successfully tested the Agni-5, a nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missile with a range of 5,000 kilometers. On March 11, 2024, India joined the ranks of global powers possessing Multiple Independently Targetable Re-entry Vehicle (MIRV) technology (The Hindu, January 4, 2022). These advancements elevate the Bay of Bengal as a pivotal arena in the naval competition between India and China, carrying profound political and strategic implications for Sri Lanka, which seeks to maintain equally friendly relations with both countries.

Further, India’s remarkable strides in space research have cemented its status as a global power. A defining moment in this journey was the historic lunar landing on 23 August 2023, when Chandrayaan-3 successfully deployed two robotic marvels: the Vikram lander and its companion rover, Pragyan. They made a graceful touchdown in the Moon’s southern polar region, making India the fourth nation to achieve a successful lunar landing. This milestone has further reinforced India’s position as an emerging great power, enhancing its credentials to assert itself more confidently in South Asian, Indian Ocean, and global power dynamics.

India envisions a stable and secure South Asia as essential to its emergence as a great power in the Indian Ocean and global strategic arenas. However, it does not consider Pakistan to be a part of this stability that it seeks. Accordingly, when India launched the ‘Neighbourhood First Policy’ in 2008 to strengthen regional ties, Pakistan was excluded. India’s ‘Neighbourhood First Policy’ gained renewed momentum after 2015 under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. His approach to South Asia is embedded in a broader narrative emphasising the deep-rooted cultural, economic, and social exchanges between India and other South Asian countries over centuries. India’s promotion of heritage tourism, particularly the ‘Ramayana Trail’ in Sri Lanka, should be viewed through this strategic lens as part of its broader strategic narrative.

Evolving Indian Ocean Geo-political Dynamics

The Indian Ocean constitutes the next geopolitical frame for Sri Lanka’s foreign policy. The Indian Ocean is a huge bay bordered by the Afro-Asian landmass and Australia on three sides and the South Asian peninsula extends into the Indian Ocean basin centrally. Situated at the southern tip of South Asia, Sri Lanka extends strategically into the heart of the Indian Ocean, shaping its geopolitical significance and strategic imperatives for maintaining sovereignty. Historically, Sri Lanka has often been caught in the power struggles of extra-regional actors in the Indian Ocean, repeatedly at the expense of its independence.

Sri Lanka’s leadership at the time of independence was acutely aware of the strategic significance of the Indian Ocean for the nation’s survival. The first Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake, who was also the Minister of Defence and External Affair, stated in Parliament that: “We are in a dangerous position, because we are on one of the strategic highways of the world. The country that captures Ceylon would dominate the Indian Ocean. Nor is it only a question of protecting ourselves against invasion and air attack. If we have no imports for three months, we would starve, and we have therefore to protect our sea and air communications” (Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, House of Representative. Vol. I, 1 December 1947, c. 444)

As naval competition between superpowers during the Cold War extended to the Indian Ocean, following the British naval withdrawal in the late 1960s, Sri Lanka, under Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike, played a key diplomatic role in keeping the region free from extra-regional naval rivalry by mobilising the countries that were members of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). In 1971, Sri Lanka sponsored a proposal at the UN General Assembly to establish the Indian Ocean as a Peace Zone (IOPZ). While the initiative initially gained traction, it stalled at the committee stage and ultimately lost momentum.

The maritime security architecture of the Indian Ocean entered a new phase after the end of the Cold War. The United States became the single superpower in the Indian Ocean with an ocean-wide naval presence bolstered by the fully fledged Diego Garcia base. Correspondingly, the regional strategic linkages that evolved in the context of the Cold War were eventually dismantled, giving way to new strategic relationships. Additionally, three key developments with profound implications for Sri Lanka should be noted: India’s projection of political and naval power into the deeper Indian Ocean, China’s rapid economic and military rise in the region, and the entry of other extra-regional powers into Indian Ocean politics. Although Sri Lanka adopted a broader strategic perspective and a more proactive foreign policy in the 1970s, its approach to geopolitical developments in the Indian Ocean in the post-Cold War era became increasingly shaped by domestic challenges—particularly countering the LTTE threat and addressing post-war exigencies.

India’s Expanding Naval Diplomatic Role in the Indian Ocean

Parallel to its strategic rise, India has intensified its engagement in the broader strategic landscape of the Indian Ocean with renewed vigor. This expansion extends beyond its traditional focus on the South Asian strategic theatre, reflecting a more assertive and multidimensional approach to regional security, economic connectivity, and maritime diplomacy. India’s active participation in multilateral security frameworks, infrastructure investments in critical maritime hubs and strategic alignments with major global powers signify its role in the changing naval security architecture of the Indian Ocean. India’s shifting strategic posture in the Indian Ocean is reflected in the 2015 strategy document Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy. It broadens the definition of India’s maritime neighbors beyond those sharing maritime boundaries to include all nations within the Indian Ocean region (Ensuring Secure Seas, p. 23).

In 2015, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched his signature Indian Ocean diplomacy initiative, Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) to foster trust and transparency, uphold international maritime norms, respect mutual interests, resolve disputes peacefully, and enhance maritime cooperation. Strategic engagement with the littoral states in the Indian Ocean region, especially Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Seychelles, and Mauritius and Madagascar has emerged as a key component of India’s Indian Ocean naval diplomacy.

The Seychelles archipelago, located approximately 600 miles east of the Diego Garcia base, holds particular significance in India’s maritime strategy. During Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s official visit to Seychelles in March 2015, India and Seychelles signed four agreements. A key strategic outcome of the visit was Seychelles’ agreement to lease Assumption Island, one of its 115 islands, to India—a move that reinforced Seychelles’ alignment with India’s broader naval diplomacy in the Indian Ocean

Similarly, Mauritius holds a central position in India’s naval diplomacy in the Indian Ocean. During Prime Minister Modi’s visit to Mauritius in March 2015, India signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Mauritius to establish a new base on North Agalega Island, a 12-kilometer-long and 1.5-kilometer-wide Island. The base is crucial for air and surface maritime patrols in the southwest Indian Ocean. It will also serve as an intelligence outpost. In September 2016, defense and security cooperation between India and Mauritius deepened alongside the signing of the ‘Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Partnership Agreement’ (CECPA).

India’s expanding strategic interests across the Indian Ocean are reflected in its growing economic, educational, and defense collaborations with Madagascar. In 2007, India established its first overseas listening post in northern Madagascar to monitor shipping activities and intercept marine communications in the Indian Ocean. This initiative provided India with a naval foothold near South Africa and key sea-lanes in the southwestern Indian Ocean. The significance of India’s defense ties with Madagascar is further highlighted by Madagascar’s participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As a crucial hub along the Maritime Silk Road connecting Africa, Madagascar’s strategic importance is underscored in the broader geopolitical landscape.

Another element of India’s expanding naval diplomacy in the Indian Ocean is its participation in both unilateral and multilateral anti-piracy operations. India’s commitment to regional security was reinforced in 2008 when it established a ‘Strategic Partnership’ with Oman, securing berthing and replenishment facilities for its navy, along with a strategically significant listening post in the Western Indian Ocean. India’s naval presence in the Arabian Gulf gains additional significance amid reports of a new Chinese naval base in Djibouti and recent submarine deployments. Successful anti-piracy missions in the western Indian Ocean underscore India’s growing influence in the region’s evolving naval security architecture.

India increasingly views its vast Diaspora as a soft power tool to bolster its status as an Indian Ocean power. In June 2014, it launched the Mausam project to reinforce its cultural ties across the region, showcasing its heritage, traditions, and contributions to global arts, literature, cinema, yoga, and cuisine. This initiative complements India’s expanding naval diplomacy and strategic presence in the Indian Ocean. Over the years, it has established listening facilities, airfields, and port infrastructure in key locations such as northern Madagascar, Agaléga Island (Mauritius), and Assumption Island (Seychelles). This has led India Today to ask: “Could this mark the emergence of an Indian ‘String of Flowers’ to counter China’s ‘String of Pearls’?” (The be continued)

by Gamini Keerawella

Features

Greener Pastures, Mental Health and Deception in Marriage:

Exploring Sunethra Rajakarunanayake’s Visachakayo

Sunethra Rajakarunanayake’s Sinhala novel Visachakayo (published in 2023) is a thriller in its own sense due to its daring exploration of social themes that modern Sinhala writers fail to touch. To me, the novel is a mosaic that explores pressing issues that middle-class Sri Lankans go through in the 21st Century. The narrative is seen from the perspective of Akshara, a Tamil girl whom the reader first meets in an infamous ‘Visa Queue’ to get her passport to go to England.

Akshara lives with her grandmother ‘Ammamma’ and her aunt ‘Periyamma’ (the younger sister of her mother). Both Ammamma and Periyamma look after her in the absence of her mother, Chinthamani who passed away a long time ago. Akshara’s father lives in Jaffna, with the kids of the second marriage. Later, we are told that Akshara’s father had to marry the second wife due to the loss of his wife’s first husband, who was an LTTE cadre. The second marriage of men seems to be a common theme in the novel due to their commitments to the family as an act of duty and honour.

The most iconic character in the novel is Preethiraj, ‘the man with a big heart’ who functions as a father figure to the other characters in the novel. It is through Preethiraj’s memory that the reader becomes aware of sociological themes in the novel: displacement and immigration, the institution of marriage and mental health issues. Preethiraj (fondly known as Preethi) is the son of Pushpawathi, the second wife of Akshara’s grandfather. Preethi goes to Royal College, but he has to relocate to Jaffna in 1958. Preethi endures social injustice in both public and private spheres. His studious sister, a medical student, labels him as a ‘lunatic’, while his mother condemns him as the ‘odd one’.

The novel intersects between the three themes: immigration and displacement, mental health issues and the institution of marriage. Almost all the characters have to go through displacement, suffer from intricacies of love laws and marriage rules like in The God of Small Things by Arundathi Roy. The writer offers a nuanced analysis of these three themes. For example, take mental health issues. The novel portrays a spectrum of mental health issues, such as schizophrenia, psychosis, Othello Syndrome, depression, autism and even malingering. At times, the representation of such ailments is extremely sarcastic:

“Hm… Canadian citizenship is an easy solution to secure those opportunities. However, unless I am asked to intervene, I will not meddle with their affairs. The son of one of my friends was introduced to a pretty girl. They liked her, not because of her money, but because of her looks and her ability to play the piano. But later, they discovered she has schizophrenia. Now their son follows whatever she says to save the marriage. My friend says she has lost her son” (p.20).

“Those opportunities” refer to material wealth including money and property in Colombo. Here, Rajakarunanayake does not fail to capture the extreme materialism and consumerism. However, in general, her representation of human follies is extremely humane.

The title ‘Visachakayo’ is another interesting coinage that reflects the plight of Sri Lankans who migrate to the ‘global north’ in search of greener pastures. Akshara’s friend, Subhani, who has migrated to England, explains that the term ‘Visachaya’ captures the in-between status of immigrants who are waiting for PR in a foreign country. Subhani mockingly says that they are equal to beggars who beg for visas. Subhani’s coinage and other accounts of Sri Lankan immigrants in England, the novel shows how difficult it is for an immigrant from the ‘global south’ to fight for a living in a country like England where immigrants come to resolve their financial struggles back home.

The novel is an eye-opener in many ways. First, it is an attempt to bridge the gap caused by the Sinhala-Tamil ethnic strife. It is also a cultural mosaic that captures both the joys and sorrows of Sinhala, Tamil and Burgher families in Sri Lanka. The novel also delves into mental health issues, categorically tied to marriage, a daring task even for a seasoned writer. However, Rajakarunanayake’s writing style compels the reader to adopt a more humane and empathetic approach towards individuals grappling with mental health challenges at various stages of their lives. The linguistic technique of using ‘ne’ tag at the end of sentences creates a conversational tone, making the narrative as if it is a conversation between a therapist and a patient. Her writing style also resembles that of Sri Lankan and Indian diasporic writers, a style that is used when writing about the motherland in exile, of which food becomes a critical trope in the narrative that unites the characters who live in exile.

Rajakarunanayake has done a commendable job in the representation of social issues, making this novel a must-read for anyone who is interested in researching social dynamics of contemporary Sri Lanka. It soon needs to be translated into English which will offer a unique experience to Sri Lankan English and international readers. A good book is something that affects the reader. Visachakayo has this quality, and it makes the reader revisit the past, reflect on the present and anticipate the future with hope for humanity just as Preethi does regardless of hardships he endured in the theatre of life.

By C. M. Arsakulasuriya

Features

A strategy for Mahaweli authority to meet future challenges amidst moves to close it down

The potential available in lands under Mahaweli Project, which cover about one third of farming areas of the Dry Zone, could easily help the country become self-sufficient in healthy foods, provided it is managed properly. However, at present, the main focus of the Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka (MASL) is mainly on Operation & Maintenance of Canal network feeding the farms. Main purpose of the Mahaweli Restructuring & Rehabilitation Project (MRRP) funded by the World Bank in 2000 was to diversify that objective to cover enhancement of agriculture aspects also. System H Irrigation Systems covering about 20,000 Hectares commanded under Kalawewa Tank located in the Anuradhapura District was used as a pilot area to initiate this effort. However, only the Canal Rehabilitation component of the MRRP was attended because of the government policy at that time. Restructuring component is still awaiting to be completed. Only, a strategy called Water Quota was introduced under the MRRP to initiate the restructuring component. However, the management restructuring required addressing the agriculture component expected under MRRP is still not attended.

Propose Strategy

Total length of the canal network which needs seasonal maintenance is about 1,000 Km in a typical large-scale irrigation project such as Kalawewa. Main role of the Resident Project Managers (RPM) appointed to manage such projects should be to enhance the food production jointly with the Farmer Organizations. Therefore, the abbreviation used for RPM should be redefined as Resident Production Manager. The role of a Production Manager is not limited to maintenance of canal networks as adapted presently. In the current production phase, Irrigation projects should be perceived as a Food Producing “Factory” – where water is the main raw material. Farmers as the owners of the factory, play the role of the labour force of the factory. The Production Manager’s focus should be to maximize food production, deviating from Rice Only Mode, to cater the market needs earning profits for the farmers who are the owners of the “factory”. Canal systems within the project area which need regular maintenance are just “Belts” conveying raw materials (water) in a Typical Factory.

Required Management Shift

In order to implement the above management concept, there is a need for a paradigm shift in managing large scale irrigation projects. In the new approach, the main purpose of managing irrigation systems is to deliver water to the farm gate at the right time in the right quantity. It is a big challenge to operate a canal network about 1000 KM long feeding about 20,000 Hectare in a typical Irrigation System such as Kalawewa.

It is also very pathetic to observe that main clients of irrigation projects (farmers providing labor force) are now dying of various diseases caused by indiscriminate use of agrochemicals. Therefore, there is a need to minimize the damages caused to the ecosystems where these food production factories are located. Therefore, the management objectives should also be focused on producing multiple types of organically grown crops, profitably without polluting the soil and groundwater aquifers causing diseases like Kidney Failures.

Proposed Management Structure

Existing management staff should either be trained or new recruitments having Production Engineering background, should be made. Water should be perceived as the most limited input, which needs to be managed profitably jointly with the farming community. Each Production Manager could be allocated a Fixed Volume of water annually, and their performance could be measured in terms of $s earned for the country per Unit Volume of water, while economically upgrading a healthy lifestyle of the farmers by using climate smart agriculture.

In addition to the government salary, the production management staff should also be compensated in the form of incentives, calculated in proportion to income generated by them from their management areas. It should be a Win-Win situation for both farmers as well as officers responsible for managing the food production factory. Operation of the Main Canal to cater flexible needs of each factory is the main responsibility of the Resident Production Manager. In other countries, the term used to measure their performance is $ earned per gallon of water to the country, without damaging the ecosystem.

Recent Efforts

Mahaweli Authority introduced some of the concepts explained in this note during 2000 to 2006, under MRRP. It was done by operating the Distributary canals feeding each block as elongated Village Tanks. It was known as the Bulk Water Allocation (BWA) strategy. Recently an attempt was made to digitize the same concept, by independently arranging funds from ICTA / World Bank. In that project, called Eazy Water, a SMS communication system was introduced, so that they can order water from the Main Reservoir by sending a SMS, when they need rather; than depend on time tables decided by authorities as normally practiced.

Though the BWA was practiced successfully until 2015, the new generation of managers did not continue it beyond 2015.

Conclusion

The recent Cabinet decision to close down the MASL should prompt the MASL officers to reactivate the BWA approach again. Farmer Organisations at the distributary canal level responsible for managing canal networks covering about 400 Hectares can be registered as farmer cooperatives. For example, there are about 50 farmer cooperatives in a typical irrigation project such as Kalawewa. This transformation should be a gradual process which would take at least two years. I am sure the World Bank would definitely fund this project during the transition period because it is a continuation of the MRRP to address the restructuring component which was not attended by them in 2000 because of government policy at that time. System H could be used as a pilot demonstration area. Guidelines introduced under the MRRP could be used as tools to manage the main canal. World Bank funded Agribusiness Value Chain Support with CSIAP (Climate Smart Irrigated Agriculture Project) under the Ministry of Agriculture which is presently in progress could also provide necessary guidelines to initiate this project.

by Eng. Mahinda Panapitiya

Engineer who worked for Mahaweli Project since its inception

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoColombo Coffee wins coveted management awards

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoStarlink in the Global South

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDaraz Sri Lanka ushers in the New Year with 4.4 Avurudu Wasi Pro Max – Sri Lanka’s biggest online Avurudu sale

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoStrengthening SDG integration into provincial planning and development process

-

Business3 days ago

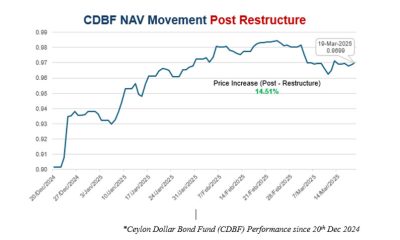

Business3 days agoNew SL Sovereign Bonds win foreign investor confidence

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTo play or not to play is Richmond’s decision

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoModi’s Sri Lanka Sojourn

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoNew Zealand under 85kg rugby team set for historic tour of Sri Lanka