Features

On a day like this 35 years ago INTAKE 20 was Commissioned

by Nilakshan Perera

On a day like this on Jan 18, 1985, some 35 years ago, there was a call for brave patriotic youth to come forward to lead soldiers to safeguard the Nation. A total of 1,039 applicants responded. After six interviews, young blood from leading schools who excelled in sports and extracurricular activities among others both at school and national level were selected. It was a unique achievement and indeed a tremendous honour for the selected 35 to gather at Army Headquarters.

After saying goodbye to our families, and knowing we had taken our first steps to embark on our chosen career, we knew that the future was not going to be a bed of roses but we were ready to take on this challenge. All 35 selected were turning their backs on cushy, white collar jobs in air-conditioned offices. They had answered the call from their hearts.

These cadets, promising future officers, were seated in an Army bus while their baggage in trunks was loaded into an Army 1210 Tata truck. We left Army HQ by 1730 hrs heading for Diyatalawa. It was around 0110 hrs next day when our journey came to an end near the Polo Grounds at Diyatalawa. This is the only natural playground in Sri Lanka used for rugby, soccer, and athletics with an adjoining golf course. It is also used as a small airfield for light aircraft. We were told the engine of the bus had overheated and the radiator was boiling and ordered by Staff Sgt Dharmasena of the Artillery Regiment and Sgt Piyasdasa of Gemunu Watch to debus as it would go no further.

To our surprise neither the bus nor the truck could be started. We assumed that this may have been due to continuous driving without a break for over six hours. Even though we were dressed in suits as we got off the bus, the temperature of 6-7o C virtually froze us in our tracks. No sooner we alighted from the bus we were asked to run to a place called Pandama, (Torch) which was the unique symbol of the Military Academy – a burning torch fixed atop a lamp-post. This eternal flame symbolizes life, dedication, and regenerative power.

By this time all of us were shivering as we doubled past the main gate of the Sri Lanka Military Academy. We had fleeting glimpses of the parade ground that was shining with frosty dew. Beyond the ground we saw a huge Makara Thorana (Dragon Arch) past which newly commissioned young officers would march. Just as we reached the ‘Pandama’, the bus and the truck which were supposedly stalled, arrived miraculously! It was only when we were asked to unload our baggage that we realized that there was nothing wrong with the vehicles. They had only wanted us to enter the Military Academy on the double – a long-established tradition.

The full moon was shining brightly in a clear sky as it was a Poya day. We could see the surrounding area more clearly now. We were taken to a place called Beast Billet, which was to be our new “home” where our sleeping accommodation was located. There was a smart Warrant Officer (WO) who showed us the green bush and grass covered area adjoining the billet. He ordered us in a commanding tone to clean and have it neat and tidy next day (a Poya holiday) as he didn’t want to see any reptiles on the ground. He then asked us to go to sleep.

The next morning after breakfast we were asked to get into our PT kit. Sgt Piyadasa took us to Q (Quartermaster’s) stores and drew us tools such as mammoties, knives, grass cutters etc. to tidy the green area. Later in the evening the same Warrant Officer ordered us to be ready in full suit next morning as he was going to take us on our ‘camp tour’ .

This Warrant Officer 1 was Chandra Abeykoon, who had just returned from a Drill Instructor’s Training course at the Guards Depot at Pirbright in UK. His boots were polished to a mirror shine and his uniform was impeccable.

Next morning, we were dressed in full suit again and taken to Army QM stores. We were issued various items, such as mess tin, water bottle, cup and plate, ground sheet, boots, canvas shoes, blankets, beret, etc. We were asked to pack all these items into a duffle bag called ‘Ali Kakula’, as it resembled the leg of an elephant. We were then taken on the double on our ‘camp tour’ by WO1 Abeykoon, Staff Sgt Dharmasena, Sgt Piyadasa, Sgt Wijeratne and PTI Cpl Mendis. We were shown the boundaries of the Military Academy and the out of bounds areas, recreational grounds, cinema hall, polo grounds, Halangoda Lake, White Gate (a small white gate leading to the officers’ mess of the Gemunu Watch at the top of a hill above the polo grounds. The whole tour was done on the double, and that was how we moved for the next six months – no walking. We had to be alert and keen. Everywhere we went we had to go on the double, sometimes doing forward rolls (a rolling mode of moving) too.

Our Chief Instructor was Maj Nihal Marambe of the Armoured Corps and our first Course Commander was Major Gamini Balasuriya, also of the Armoured Corps, and later Capt Rohan Induruwa from Sinha Regiment,

Our billet was called Beast Billet. As the name implies, we were fondly taken for beasts. There was no relaxing and we were always on the move from one task to another. Our only consolation was to receive an occasional letter from home. From the Beast Billet we could clearly see three railway stations on mist free nights. These were Idalgasshinna, Haputale and Diyatalawa. We often imagined that we were seated in the train and going home on vacation and a few of us sometimes became emotional. We waited to hear the train approaching through the hills of Idalgasshinna. Early in the morning when we getting ready for PT, we could see it moving slowly like several boxes of matches coupled together and we knew that letters for us would be by delivered by afternoon. The same way our letters home would be carried in the night mail train leaving Diyatalawa every evening at 1940 hrs.

It was a part of the Duty Orderly Cadet’s tasks to collect the daily mail from the office and to hand over any mail that was to be posted. All of us were delighted to receive a letter or two from home. While those of us who got mail were rejuvenated, the few who didn’t were dejected. Getting letters was one of the few joys of life we enjoyed at that time.

We were taken for physical training, drill and weapon training, map reading, field craft, and tactics during morning sessions. In the afternoon we were taught leadership, military law, current affairs and English. We were taught Tamil by a civilian teacher from Bandarawela, our only civilian teacher, and we were very relaxed and enjoyed his lessons. We had plenty of recreational facilities and games in the evening.

During the next few weeks, we were transformed from raw young men into tough military personnel and made ready to face the future. We never dreamed of a good, cozy night’s sleep in the cool of Diyatalawa because we never knew what would come next. No two nights were the same. Soon we were well prepared for whatever came, sometimes even being mocked at or ostracized.

At the end of six months we had passed our Drill and PT tests. These included several changing parades in front of Senior Intake 18A and later Intake 19, before we could go out. They checked our attire – blazer, slacks, shirt, tie, belt, shoes, and socks to ensure they matched. We were properly shaved and generally well groomed. We flocked to Bandarawela Town like homing pigeons. Some of us were at restaurants, some went to tailor shops and few went to Cyril Studio to have their photos taken. And then all of us made a beeline to the Bandarawela Post Office to make telephone calls home and to friends. There were no pay phones then in the Academy, Mobile phones, WhatsApp, Viber, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram etc. were not even in the lexicon. Wherever we went we had to walk in step and in pairs. We never knew who would report wrongdoings to SLMA. The whole town knew we were cadets from the Academy.

To our great delight we soon got to share rooms with a batch mate. We had our first seven-day vacation after passing the drill and PT test. However, during this vacation each of us had to research material for our Leadership Presentations of famous political, military, and historical figures. We were expected to be ready with view files, photographs, scripts, slides, and booklets. We had to soldier through endless pages to gather the necessary information. There was no Google those days and it was a nightmare to prepare and make presentations to the instructor officers in a series of repeated sessions lasting till midnight. But the knowledge gained and efforts made were invaluable later in our lives.

Intake 19 passed out in November 1985 and we now became the Senior Intake. We were assigned individual rooms. There was Lady Intake 3, SSC (Short Service Commission) Intake 5,6,7,8 with Intake 22 & 23. There were seven Service Cadets from KDA who after completing their three and half year University degree cum military training joined us for their final term.

By this time Intake 20 was under the watchful eyes of new Course Commander Capt Jayavi Fernando from Gajaba Regiment, an amazing military man who had achieved many firsts in his career. History records he always placed his boundless talents at the service of the Army whenever duty called. He never dodged a responsibility, never refused to take on a hard task if it had to be done. What he believed, he believed with heart and soul. In brief, he was a patriotic and distinguished military officer, a natural leader, and an affectionate brother to all servicemen. He was loved and admired by all his superiors, colleagues and subordinates. His premature retirement as Colonel on Oct 31, 1998 was a great blow to the Army.

We were taken for firing practice including night firing to the Firing Range on various occasions as it was a part and parcel of our training. During our moves by truck to the firing range and at the Cadets’ Mess after dinner we used to sing popular Sinhala songs songs like Ae NeelaWara Peerala by Dhanapala Udawatte & ThilineLesin by Three Sisters and Asoka Mal by MS Fernando.

We went on field exercises to the landmark Foxhill area for Exercises Seetha Sulang and Grave Digger at Gurutalawa and to Ambewela for Frozen Trout living in trenches on the last exercise for six days with leeches for company and misty continuous drizzling and unpredictably cold weather. We then had Exercise Wanabambara in the dense jungles off Wellawaya for 14 days. Then Exercise God King in Kataragama. During Exercise Scorpion we practiced enforcing curfews in Welimada/Keppettipola area and searching for and detecting mock insurgents.

Our parents were invited on Parents’ Day in February for a full day program to observe their sons’ progress and development in their budding military careers.

With lot of endurance and enthusiasm we ran nine miles three times with our rifle, full water bottle (from which we could not take even a sip) and 20 kgs kit in our battle order packs along the Bandarawela/Welimada Road crossing the bridge and passing Bandarawela town, Kahagolla, and the Ceylon Volunteer Force camp to the Academy Gym.

The Intake 20 boxing meet was held on April 11, 1986, at the gymnasium. We were matched according to our weights and boxed each other with gusto. It is no friendly Charlie Charlie game; we were told to draw blood from our opponent. All Officer Instructors of SLMA, Capt Rohan Jayasinghe, Capt Jagath Rambukpotha, Capt Aruna Wijenayake, and Lt Mahesh Senanayake acted as judges. Commandant Col Rohan de S Daluwatte was the Chief Guest.

On Vesak Poya night, after dinner some trainee teachers from Bandarawela performed Bhakthi Gee for us at the Cadets’ Mess. Soon after they left a few of us sought permission from the Course Officer to go out to see the Vesak decorations. We didn’t get that permission but the whole Intake was made to circle the Cadet’s Mess singing Bhakthi Gee, This went on non-stop for three or four hours. No one ever after requested permission to go out to see Vesak illuminations!

In May we were taken on Unit visits. We were all stationed at Kotelawala Defence Academy for eight days during which we visited all unit HQs in Colombo and Panagoda. On our return, we were given motorcycle riding lessons at Polo grounds in the mornings as we prepared for the Commissioning Parade on May 31.

Four years after Intake 16 we were greatly honoured to have an Under Officer appointed from our batch. That was Wipula Seneviratne, as he came first in the order of merit. For our Commissioning Parade Gen Denis Perera, the first Commandant of Army Training Center and former Army Commander, took the salute.

After Commissioning as 2nd Lieutenants, we were taken to Maduru Oya for further Infantry training and then went on to our respective Units.

2/Lt Wipula Seneviratne and 2/Lt Prasanna Perera, the first two in our intake were selected to go to the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, in UK for further training. It was another unique achievement for Intake 20 as these two were the first to go to Sandhurst after a lapse of several years.

During this time, all our batch mates were in the thick of military operations in the North or the East. With deep sorrow and highest gratitude, we recall the names of our beloved batch mates who made the supreme sacrifice in defending Mother Lanka for future generations.

They were Lt Sanath Samarakoon GW (27/08/1986 Nillaweli), Lt Ananda De Silva SLA (07/10/1987-Mannar), Capt Wipula Seneviratne SLA (15/04/1988 Athurugiriya), Maj Prasanna Liyanagoda VIR (30/07/1990 – Mannar), Maj Devamiththa Dissanayake GW (01/05/1991 -Trincomalee), Lt Col B C K L Silva SLLI (13/09/1995 – Plane Crash/Kandana), Lt Col Shantha Jayaweera SLLI (17/11/1995 Jaffna) Maj Srinath Wickramasinghe SLLI (26/12/2007 Tsunami/Thelwatte), — Maj Ravi Dissanayake SLASC (20/07/2018 – Military Hospital.

When we look back, we could say with humility and pride that we served as soldiers and fought for our country with utmost dedication and commitment, in the jungles, plains, hills and valleys. We had seen our comrades lay down their lives, suffered setbacks and finally achieved victory under extremely challenging conditions.

As Intake 20 celebrated their 35th anniversary on 31 May as Commissioned Officers, let me salute all our dear batchmates who have laid down their lives for our future generations. May your journey in Samsara be short, May you all finally attain Supreme bliss of Nibbana and Rest in Peace eternal.

And best wishes to all my batch mates in their future endeavors

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

Features

Egg white scene …

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

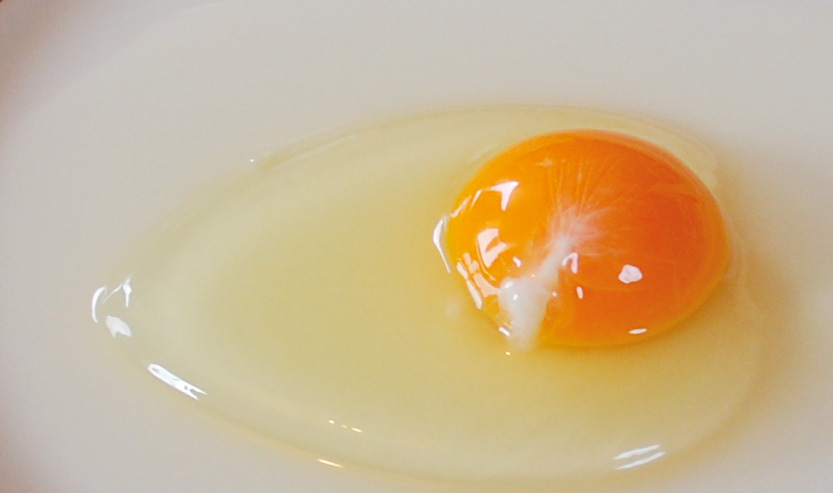

Thought of starting this week with egg white.

Yes, eggs are brimming with nutrients beneficial for your overall health and wellness, but did you know that eggs, especially the whites, are excellent for your complexion?

OK, if you have no idea about how to use egg whites for your face, read on.

Egg White, Lemon, Honey:

Separate the yolk from the egg white and add about a teaspoon of freshly squeezed lemon juice and about one and a half teaspoons of organic honey. Whisk all the ingredients together until they are mixed well.

Apply this mixture to your face and allow it to rest for about 15 minutes before cleansing your face with a gentle face wash.

Don’t forget to apply your favourite moisturiser, after using this face mask, to help seal in all the goodness.

Egg White, Avocado:

In a clean mixing bowl, start by mashing the avocado, until it turns into a soft, lump-free paste, and then add the whites of one egg, a teaspoon of yoghurt and mix everything together until it looks like a creamy paste.

Apply this mixture all over your face and neck area, and leave it on for about 20 to 30 minutes before washing it off with cold water and a gentle face wash.

Egg White, Cucumber, Yoghurt:

In a bowl, add one egg white, one teaspoon each of yoghurt, fresh cucumber juice and organic honey. Mix all the ingredients together until it forms a thick paste.

Apply this paste all over your face and neck area and leave it on for at least 20 minutes and then gently rinse off this face mask with lukewarm water and immediately follow it up with a gentle and nourishing moisturiser.

Egg White, Aloe Vera, Castor Oil:

To the egg white, add about a teaspoon each of aloe vera gel and castor oil and then mix all the ingredients together and apply it all over your face and neck area in a thin, even layer.

Leave it on for about 20 minutes and wash it off with a gentle face wash and some cold water. Follow it up with your favourite moisturiser.

Features

Confusion cropping up with Ne-Yo in the spotlight

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

At an official press conference, held at a five-star venue, in Colombo, it was indicated that the gathering marked a defining moment for Sri Lanka’s entertainment industry as international R&B powerhouse and three-time Grammy Award winner Ne-Yo prepares to take the stage in Colombo this December.

What’s more, the occasion was graced by the presence of Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs of Sri Lanka, and Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe, Deputy Minister of Tourism, alongside distinguished dignitaries, sponsors, and members of the media.

According to reports, the concert had received the official endorsement of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau, recognising it as a flagship initiative in developing the country’s concert economy by attracting fans, and media, from all over South Asia.

However, I had that strange feeling that this concert would not become a reality, keeping in mind what happened to Nick Carter’s Colombo concert – cancelled at the very last moment.

Carter issued a video message announcing he had to return to the USA due to “unforeseen circumstances” and a “family emergency”.

Though “unforeseen circumstances” was the official reason provided by Carter and the local organisers, there was speculation that low ticket sales may also have been a factor in the cancellation.

Well, “Unforeseen Circumstances” has cropped up again!

In a brief statement, via social media, the organisers of the Ne-Yo concert said the decision was taken due to “unforeseen circumstances and factors beyond their control.”

Ne-Yo, too, subsequently made an announcement, citing “Unforeseen circumstances.”

The public has a right to know what these “unforeseen circumstances” are, and who is to be blamed – the organisers or Ne-Yo!

Ne-Yo’s management certainly need to come out with the truth.

However, those who are aware of some of the happenings in the setup here put it down to poor ticket sales, mentioning that the tickets for the concert, and a meet-and-greet event, were exorbitantly high, considering that Ne-Yo is not a current mega star.

We also had a cancellation coming our way from Shah Rukh Khan, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka for the City of Dreams resort launch, and then this was received: “Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal reasons beyond his control, Mr. Khan is no longer able to attend.”

Referring to this kind of mess up, a leading showbiz personality said that it will only make people reluctant to buy their tickets, online.

“Tickets will go mostly at the gate and it will be very bad for the industry,” he added.

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRethinking post-disaster urban planning: Lessons from Peradeniya

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoAre we reading the sky wrong?