Features

Lowering the brow : The films of H.D. Premaratne

By Uditha Devapriya

The face of Sri Lankan films changed in the 1970s. This was due to a number of reasons. Arguably, the most important of them would be the rise of the Sinhala Buddhist rural petty bourgeoisie. Initially represented as side characters, they eventually became protagonists and antagonists in the films which featured them. Lester James Peries’s Golu Hadawatha and Akkara Paha broke ground, in that sense, by casting this milieu in films that not only performed well at the box-office, but also won awards, internationally.

These were decades of expansion in the university system and the public sector. The SLFP’s historic win in 1956 had secured for the Sinhala middle-class a place in the sun: that spilt over to the country’s cultural and social landscape. It was in this interregnum, between the Bandaranaike and the Jayewardene years, that pulp fiction became established in Sri Lanka, despite the opposition and resistance it provoked from the establishment. After Gunadasa Amarasekara and Siri Gunasinghe, the likes of Karunasena Jayalath gained a foothold. These developments and shifts soon extended to other art forms.

Thus it was in this interval, between the social transformation of the Bandaranaike years and the liberalisation of the cultural industries in the Jayewardene years – two processes which liberated and contributed to a decline in artistic and cultural activity – that I locate H. D. Premaratne. Together with Vasantha Obeyesekere, Premaratne redrew the frontiers of artistic and commercial cinema. This rift had emerged with the films of Lester Peries: while applauded by critics, they very often failed at the box-office. No mass culture / high culture dichotomy had prevailed before: Sinhala films, from their inception in 1947, were made to please popular audiences. Peries’s films thus heralded a radical shift in the way Sri Lankans viewed and thought about the cinema. Dharmasena Pathiraja, a critic of Peries’s work, tried, a generation later, to realise the political potential of the medium.

H. D. Premaratne emerged at this juncture. Having worked as an assistant, he made his first film, Sikuruliya (1975), around the time Pathiraja was making Ahas Gawwa. The second or so film to be shot in Cinemascope, Sikuruliya tried to achieve some kind of a compromise or balance between the demands of popular and commercial cinema. If Premaratne was, in his later years, conferred with the title of the father of the middle cinema in Sri Lanka, it is not because other directors didn’t try to chart middle ground in the Sinhala film, but because no other director succeeded in that endeavour the way he did. Sikuruliya, in that respect, is the spiritual successor to works like Dahasak Sithuvili and Hanthane Kathawa, which combined song and dance sequences with a simple naturalism of style. But the directors of these films did not replicate their initial successes. Premaratne did, again and again.

In Apeksha (1978), Premaratne tried to combine a conventional romance with class politics. There is a scene where the protagonist, played by Amarasiri Kalansooriya, poses as the rich paramour of Malini Fonseka to her father, played by the stern Felix Premawardhana. The sequence where Kalansooriya is revealed as an imposter, and then kicked out of the house, reveals the director’s class sympathies very clearly. Yet what is fascinating about Apeksha is not its class politics, but rather the way the director enmeshes them with tropes borrowed from the mainstream cinema: the hero/villain dichotomy, the triumph of good over evil, the final fight between hero and villain, and the reconciliation of the woman to the man, and the man to the father of his lover. These were years of unrest, and in depicting the conflict between rich and poor, Premaratne tries to capture that unrest.

To be sure, Premaratne does not entirely succeed in his enterprise. This is to be expected: the limitations imposed by the popular cinema tend to cripple any attempt at a political statement. Here it is interesting to compare Premaratne’s film with what his contemporary Vasantha Obeyesekere was doing at the time. Apeksha came a year before Palangetiyo, which, after Dadayama (1984), goes down as Obeyesekere’s finest work. In Palagetiyo, the director employs the tropes of the commercial cinema in several fantasy sequences: the protagonist, played by Dhammi Fonseka, is addicted to romantic fiction, and imagines a life of ease and comfort with her lover, who works under her father. By contrast, Diyamanthi (1976), also by Obeyesekere, depicts a group of teenagers who while away the time, make friends with a rich heiress (Malini Fonseka), and unravel a diamond heist.

There is a sequence in Diyamanthi which reveals the director’s attitude to the politics of rebellion: the protagonist, played by Vijaya Kumaratunga, is evicted by his landlady, played by Rathnavali Kekunawela. He is without a job. Given his credentials – he has a Bachelor of Arts, a qualification associated then as now with lack of employability – he faces a bleak future. Yet what Kumaratunga’s character does is to take his Bachelor of Arts and toss it into a trashcan nearby. Here Obeyesekere epitomises the freewheeling optimism of the youth, yet also sidesteps their growing frustrations. The contrasts with Palangetiyo and Dadayama are very clear: while Diyamanthi remains hopeful about the future, these two films suggest optimism, only to subvert it. Dadayama, in particular, has its heroine dream about marriage life with her lover, only for her to fall into one calamity after another.

Obeyesekere’s politics were centre left; Pathiraja’s were radically left. Obeyesekere’s later slide down into obscurantism, epitomised by Maruthaya (1995), pushed him away from the politics of middle period films like Dadayama and Kadapathaka Chaya (1989). Premaratne, in comparison, became increasingly commercialist in his outlook, though this did not cripple his attempts at achieving a fusion between the popular and the artistic. This fusion does not always result in artistic works: too often the commercial, mainstream aspects of his stories prevail over their political orientation. A good example here would be Parithyagaya (1980). On the surface, it’s an indictment of a cultural practice, the diga or the dowry system, which penalises poor families searching for a suitor for their daughter. The theme is handled well, and at the end, when the police come to arrest the protagonist, who robbed a store to raise money for his sister’s wedding, we feel the injustice of it all acutely.

Yet Premaratne’s concern for the downtrodden underlies a somewhat regressive outlook. In her critique of Parithgayaga (“’Parithyagaya’ – Who sacrifices what and for whom?’, Lanka Guardian, August 15, 1988, 24), Sunila Abeysekera argues that the protagonists of the story do not actively protest the dowry system, but rather acquiesce in its workings. The heroine’s brother does not question the dowry; rather, he goes on to raise it himself. The heroine’s suitor, a schoolmaster played by Tony Ranasinghe, also sidesteps the wider implications of the diga system: he merely suggests that his family want the best for him, and it would be unfair by them to ignore what they want for him. The characters who pass for villains in the story – the schoolmaster’s mother particularly – are caricatured, yet this caricaturing fails to overcome “the silent and passive acquiescence” of their victims.

I would, of course, take such critiques with a pinch of salt: as Sumitra Peries has told me regarding criticism of her own films, critics tend to assume that characters in a particular situation and context should behave in this way or that, without realising that the conditions of their existence push them to accept practices which contemporary society may consider traditionalist, regressive. But Abeysekera’s criticism should not be sidestepped either, if at all because it reveals the limits of Premaratne’s beliefs. For me those limits are epitomised, more than any other work, by Deveni Gamana (1982) and Visidela (1997): the first offers a critique of the practice of checking a woman’s virginity on her first night, the latter presents a troubled village at the time of the second JVP insurrection. Both are overwhelmed by the tropes of popular films: the woman in Deveni Gamana, rejected by her lover and his family, returns to him, while the hero of Visidela kills the man who raped his sister.

Nevertheless, Premaratne’s achievements cannot be ignored. Like Roger Corman, he never lost a cent on his films. Unlike Vasantha Obeyesekere, he did not slide into obscurantism: this is as much a testament to his artistic outlook as it is to the limitations of his politics. I think he overreached himself in his last work, Kinihiriya Mal (2001), which combines rather well a critique of Free Trade Zones and of an economic system which condemns women to prostitution, but then upends it all by drawing stereotypes of a “good” village girl (Vasanthi Chathurani) and a “bad” city girl (Sangeetha Weeraratne). “Reality,” Malinda Seneviratne wrote in his (mostly negative) review of the film, “isn’t so stark.” Perhaps not so in real life. But the reality that Premaratne occupied was different, markedly. Again, that is a testament to his outlook, as much as it is to the limitations of that outlook.

(The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com)

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

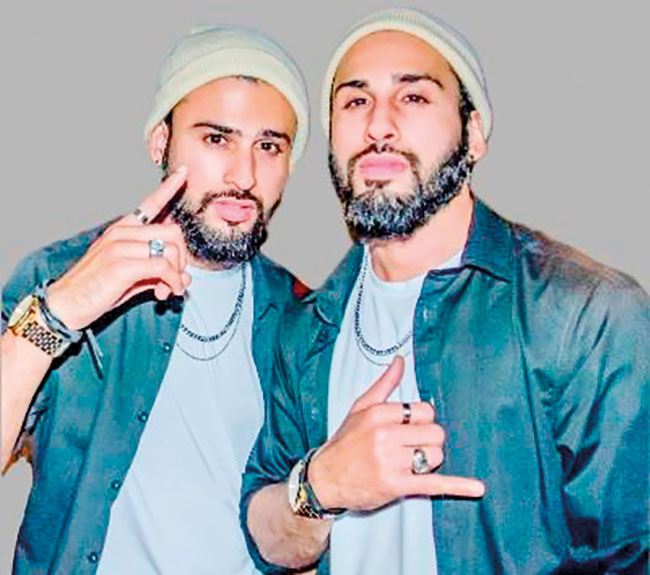

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

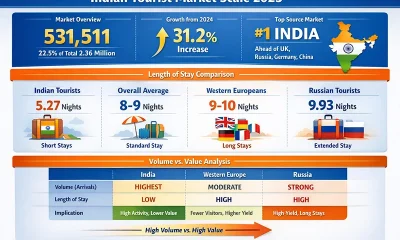

Features7 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoFuture must be won

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans