Features

London Exhibition of Universal Adult Franchise

In 1981 occurred an anniversary — fifty years after the 1931 constitutional change through which Ceylon was awarded universal adult suffrage. This was deemed an anniversary which richly deserved appropriate celebration. J R handed the matter over to Premadasa, and he in turn asked me to coordinate it. This meant making arrangements for a national celebration on an appropriate scale and an exhibition of the Sri Lankan heritage, both in London and Washington.

We needed a suitable partner in London to mount the exhibition which would make an impact, and the Commonwealth Institute in Kensington offered the logical choice. James Porter, the director of the Institute at that time gave his total support and the London Exhibition which lasted one month, was a great success. It was opened by Her Majesty, the Queen, who spent over an hour going through the exhibits, and a number of members of the British Cabinet and our own Cabinet paid visit. Premadasa joined the Queen in a very impressive ceremony conducted at the Commonwealth Institute building. Porter became a great friend and, in his letters, would retell how well the Sri Lanka exhibition had gone and been received. The Tara, the eighth-century priceless we borrowed from the London Museum, was the prime exhibit and we added to its public attraction by placing a cobra hi bit inside the glass box, which contained the goddess. It was immensely popular. Sri Lanka got a great deal of positive publicity. The picture -“the Avalokateswara Bodhisatwa” which we used as the ikon for the exhibition became a favoured symbol of Sri Lanka for years to come.

But just before leaving for London came a bombshell. J R said we could only take the replicas of the priceless art exhibits, we had catalogued, to London. Not the real things. The quiet and demure Elina Jayewardene, J R’s wife had been asking questions at the breakfast table and J R had promised an answer next morning. “What if the ship sank?” “What if the plane crashed?” “What if they were stolen?” We went to Ward Place that evening and pleaded with Mrs Jayewardene that the originals of most of the items had to be sent, otherwise the exhibition would be a flop. I said that I would take full responsibility for bringing back safely each and every piece. It was quite an undertaking but the only way to overcome the crisis. She finally relented but it was a close call.

The exhibition which was opened with great ceremony on the 19th of July by the Queen was an outstanding success. The one discordant note was the commotion made by a group of Tamil expatriates outside on Kensington High Street who waved placards denouncing the fake democracy in Sri Lanka. The High Commission tried to counter this by referring to our ability to change governments virtually every five years. This was the proof, if any were needed, of a vibrant democracy at work.

The 1983 Pogrom

In July 1983, there occurred the worst exhibition of communal violence that the country had witnessed. Those of us who lived through this period and saw some of it will never be able to erase from our minds the horrible acts inflicted on innocent people and the fear that engulfed thousands.

I was called upon to play a special role in restoring essential services island-wide. J R summoned me to his office on Wednesday afternoon of that fateful week as the rioting — which in Colombo was entirely one-sided — continued unabated. The burning and looting had started, after the news spread of the death of 13 soldiers caught in an ambush in Tinneveli on Friday night. The mass funeral was scheduled for Sunday afternoon at Kanatte cemetery and the mood turned ugly. As he spoke about appointing me commissioner-general of essential services with wide powers to stop the violence and restore normalcy, rampaging mobs were on the streets, pulling Tamil people out of vehicles and assaulting them and where there was resistance and the locking of doors, setting fire to the vehicles themselves with people inside them. It was chaotic, the mobs appeared to have gone mad and Colombo was burning.

Since the president had appointed me it was my duty to keep him informed of progress and to get directions on other lines of action that I might take. Premadasa, under whom I served as secretary, also assumed he had a hand in my work as commissioner-general and once or twice called in at the Royal College Head Quarters of the CGES to see how things were going. He did not seem to want to change anything but clearly wished to be seen as someone who was responsible too for the early restoration of essential services. He changed nothing of what I was doing and once he knew that the work was going on speedily, hardly intervened at all. So, the two jobs were separate and, in a sense, I now had two masters to serve.

I had now to see J R often and in action at moments of crisis. I could not but be impressed with his ability to remain calm excepting in the most difficult circumstances. One such was the second attack on the Tamil remand prisoners in Welikada jail on the 24th of July 1983. We were all at the Army Headquarters on Lower Lake Road when the news came in about the attack. The first which had occurred a day or two earlier, had resulted in the bludgeoning to death of around 30 remand prisoners including Kuttimani. Kuttimani had said somewhere that he was happy to be living at this time so that he could see the birth of Eelam with his own eyes. It was said that the enraged prisoners who had attacked the group of remand prisoners—among whom was Kuttimani—were so angry that they had claimed after the event that they had taken out the eyes of Kuttimani.

The Truth Commission in its report of September 2002 referred to the incidents at the Welikada Prison on the 25 and 26th of July 1983 as some of the most agonising moments of challenge to the nation’s collective conscience. Fifty-two political prisoners, some them in remand, some only under detention, were done to death by other inmates of the prison at that time. According to eye witness accounts, the Tamil prisoners taken in under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) were held in wards which were broken into by around 400 other prisoners armed with clubs.

C T Jansz, who was the acting commissioner of prisons informed J R at a meeting at which I was present at the army headquarters on the afternoon of 27 July that a further 15 had been killed. The first attack on 25 July had resulted in the death of 35 and of those killed on 25 July was Kuttimani alias K Yogachandran.

J R was trembling with rage when informed that the army guard on duty at the gate of the prisons had not intervened, in spite of his instructions after the first attack. The government had to hear much adverse comment on this murder of persons who were under state protection.

A further challenge was that the government did not take any worthwhile action against those responsible for the incidents.

The news of the second attack was personally brought to J R by C T Jansz, the commissioner of prisons, who was visibly shaken at the turn of events, and confessed that the prison guards had been no match for the assault on the high security area which housed those who remained after the first attack. Around 10 remand prisoners were done to death again and J R was angry, that in spite of his earlier orders that security should be enhanced the deed was not done.

On an earlier occasion after my first round of the Colombo city on being appointed as commissioner general, I reported back to J R at his Ward Place residence and mentioned that the situation was terrible with homes being attacked and cars being set on fire. I actually asked him whether he would like to go around the city and look at the burning buildings. I began to make a point that since the police and the armed services did not appear to be over- zealous in dealing with the looters, he might consider asking India for some help with commandos or paratroopers to save the persons under threat. I casually dropped in the thought that in 1915 the then government had to bring in some Sikhs and Punjabis to stop the Sinhala and Muslim riots. J R of course knew all about the history but shrugged it off and explained to me coolly saying – when a great wind blew with gale force it was unstoppable and all you could do was bend with the wind but that the wind would not go on forever. But when it ceased, the trees that bent would come back to normal. I was amazed at the metaphor but realized that this was the wisdom of a very pragmatic and an experienced politician.

Before I could even organise myself, and while in office on Black Friday, I was to be a personal witness to the fear that gripped Colomboites as a rumour spread that Tamil militants had been seen on a balcony of a Pettah toy-shop. I have never seen such a quick exodus of people from their offices as on this morning when everyone rushed for the bus, leaving even handbags and slippers behind in a mad scramble. Coincidentally, Narasimha Rao – the foreign minister of India – was in town conferring with J R on the help that India could give to contain the emergency. That Friday as I moved slowly home along Duplication Road, the prime minister’s office also having closed early, at the Vajira Road intersection, a frenzied mob, bare-bodied and with sarongs tucked-up, brandishing swords and clubs, ran upwards towards Galle Road, the Hindu kovil at Bambalapitiya being their target. I shuddered at what fate awaited the pusari and his family and my own impotence at the time.

At 3.00 pm the long-awaited curfew was announced but it did not deter a small group of drunken rowdies from shouting, a few hours later, as they stood at the top of de Fonseka Place, where I lived, as to whether there were Tamils still living down the street. I decided that I had to confront them and, in spite of Damayanthi warning me to come back, I went out to meet them. The more sober among them produced a sheet of paper on which the numbers of some houses were written. I said I was sure they had all left already but they were not convinced. Seeing that I appeared to have some authority, although I had no security of any kind at the time, and had changed into my sarong and banian, they reluctantly turned away, muttering vile imprecations and questioning my patriotic sensibilities. In fact, as it turned out, my friends, especially the retired bank executive Ladd Mahesan, who lived a few doors away and would greet me with a bow of his head as he passed by each morning on his way to play tennis, were already relatively safe from physical attack in the hastily set-up welfare camp at the Wellawatte Hindu College a few miles away.

J R invested me with enormous power as commissioner-general of essential services. I had the power to requisition buildings, aircraft, ships, trucks, trains and even people. He allotted a sum of Rs 50 Million, which was a big sum in those days, to get on with the job; to try and work towards normalcy, as soon as possible. I had to set up an organisation from scratch. As a headquarters, I chose Royal College, since all schools were closed and the students had been given an extended holiday. I converted a part of the college into an office and had a staff of five personally chosen top administrators to assist me as commissioners within two days. I offered them interesting work and highly enhanced salaries. Their first job was to choose ten others – from executives to drivers – to handle their separate portfolios. I had worked with my top team before in difficult situations and they, each and everyone of them, did an outstanding job.

They were Manel Abeysekera, a friend from the foreign service, S Sivanandan, my deputy when I was GA at Galle and Ampara, Yasasiri Gunawardena, My assistant at Galle. I chose Wing Commander Raja Wickremasinghe to organise air evacuation for those who wanted to fly to the east or to the north and soon he had a little domestic air service going with two Dakotas in hand. Wilfred Jayasuriya, the former director of commerce and writer, provided the media and communication support.

We had enormous help from the civil society and recognised NGOs like Sarvodaya, Red Barma, LEADS, SEDEC, the Red Cross, and many others who took over the delivery and distribution of food at the welfare camps and helped with providing medical attention. At the time we had virtually no international agencies who could be asked to help and sadly no disaster relief preparedness, machinery, or financial reserves. It had to be for many months a purely local initiative sustained by volunteer effort and commitment.

In a few days after the initial attacks on people and homes in Colombo and the suburbs, the refugee population swelled to over a 125,000 in the city alone. We had soon sixty welfare camps ranging from the large ones at Kotahena Church, Thurstan College and the Ratmalana Hindu College to little ones catering to 10 to 12 families. Each of them had to be provided with the basic facilities of food, water and sanitation. For security we had to depend on the police and army.

I tried as far as humanly possible to visit all of these centres and to re-assure the victims of assault and the pillage of their possessions, that the state had not forgotten them and would work to restore whatever was possible of their loss and most importantly their dignity. At the airport hangar in Ratmalana which was converted into a huge welfare camp I found a friend Jolly Somasunderam, a senior public servant whose home had been broken into and who had fled with his family in the nick of time. I offered to take him back home but he preferred the relative safety of the camp until things returned to normal. His stoic refusal to despair and run away to another country, and his faith in the healing process which the passing of time would bring was very reassuring. As a Tamil he had been through this before. I found another man in the hangar, close to tears and he begged of me to find his wife and daughter who had been separated from him as they fled their home one night. He had heard that they might be in the St Lawrence Church in Wellawatte. I said, ‘Lets try’ and took him in my car to the Church where indeed they were. Years later I ran into him at a seminar on conflict resolution and tears of joy ran down his face at the recollection of the incident. (To be continued)

(Excerpted from Rendering unto Caesar, autobiography of Bradman Weerakoon)

Features

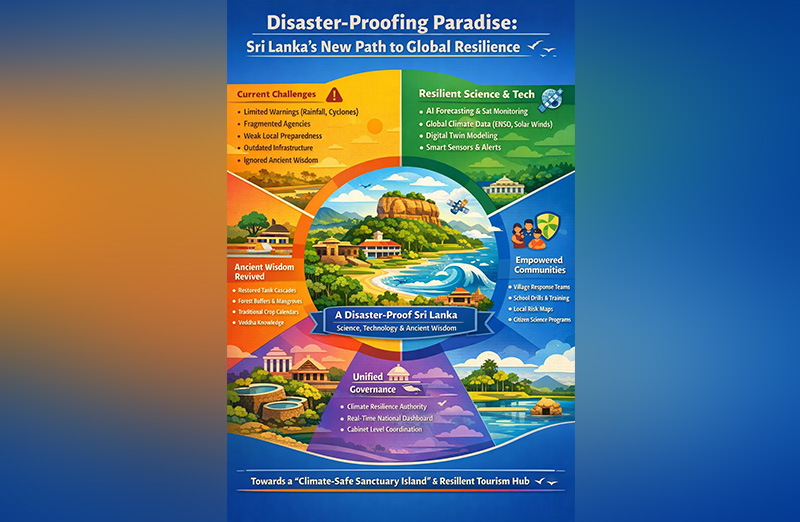

Disaster-proofing paradise: Sri Lanka’s new path to global resilience

iyadasa Advisor to the Ministry of Science & Technology and a Board of Directors of Sri Lanka Atomic Energy Regulatory Council A value chain management consultant to www.vivonta.lk

As climate shocks multiply worldwide from unseasonal droughts and flash floods to cyclones that now carry unpredictable fury Sri Lanka, long known for its lush biodiversity and heritage, stands at a crossroads. We can either remain locked in a reactive cycle of warnings and recovery, or boldly transform into the world’s first disaster-proof tropical nation — a secure haven for citizens and a trusted destination for global travelers.

The Presidential declaration to transition within one year from a limited, rainfall-and-cyclone-dependent warning system to a full-spectrum, science-enabled resilience model is not only historic — it’s urgent. This policy shift marks the beginning of a new era: one where nature, technology, ancient wisdom, and community preparedness work in harmony to protect every Sri Lankan village and every visiting tourist.

The Current System’s Fatal Gaps

Today, Sri Lanka’s disaster management system is dangerously underpowered for the accelerating climate era. Our primary reliance is on monsoon rainfall tracking and cyclone alerts — helpful, but inadequate in the face of multi-hazard threats such as flash floods, landslides, droughts, lightning storms, and urban inundation.

Institutions are fragmented; responsibilities crisscross between agencies, often with unclear mandates and slow decision cycles. Community-level preparedness is minimal — nearly half of households lack basic knowledge on what to do when a disaster strikes. Infrastructure in key regions is outdated, with urban drains, tank sluices, and bunds built for rainfall patterns of the 1960s, not today’s intense cloudbursts or sea-level rise.

Critically, Sri Lanka is not yet integrated with global planetary systems — solar winds, El Niño cycles, Indian Ocean Dipole shifts — despite clear evidence that these invisible climate forces shape our rainfall, storm intensity, and drought rhythms. Worse, we have lost touch with our ancestral systems of environmental management — from tank cascades to forest sanctuaries — that sustained this island for over two millennia.

This system, in short, is outdated, siloed, and reactive. And it must change.

A New Vision for Disaster-Proof Sri Lanka

Under the new policy shift, Sri Lanka will adopt a complete resilience architecture that transforms climate disaster prevention into a national development strategy. This system rests on five interlinked pillars:

Science and Predictive Intelligence

We will move beyond surface-level forecasting. A new national climate intelligence platform will integrate:

AI-driven pattern recognition of rainfall and flood events

Global data from solar activity, ocean oscillations (ENSO, MJO, IOD)

High-resolution digital twins of floodplains and cities

Real-time satellite feeds on cyclone trajectory and ocean heat

The adverse impacts of global warming—such as sea-level rise, the proliferation of pests and diseases affecting human health and food production, and the change of functionality of chlorophyll—must be systematically captured, rigorously analysed, and addressed through proactive, advance decision-making.

This fusion of local and global data will allow days to weeks of anticipatory action, rather than hours of late alerts.

Advanced Technology and Early Warning Infrastructure

Cell-broadcast alerts in all three national languages, expanded weather radar, flood-sensing drones, and tsunami-resilient siren networks will be deployed. Community-level sensors in key river basins and tanks will monitor and report in real-time. Infrastructure projects will now embed climate-risk metrics — from cyclone-proof buildings to sea-level-ready roads.

Governance Overhaul

A new centralised authority — Sri Lanka Climate & Earth Systems Resilience Authority — will consolidate environmental, meteorological, Geological, hydrological, and disaster functions. It will report directly to the Cabinet with a real-time national dashboard. District Disaster Units will be upgraded with GN-level digital coordination. Climate literacy will be declared a national priority.

People Power and Community Preparedness

We will train 25,000 village-level disaster wardens and first responders. Schools will run annual drills for floods, cyclones, tsunamis and landslides. Every community will map its local hazard zones and co-create its own resilience plan. A national climate citizenship programme will reward youth and civil organisations contributing to early warning systems, reforestation (riverbank, slopy land and catchment areas) , or tech solutions.

Reviving Ancient Ecological Wisdom

Sri Lanka’s ancestors engineered tank cascades that regulated floods, stored water, and cooled microclimates. Forest belts protected valleys; sacred groves were biodiversity reservoirs. This policy revives those systems:

Restoring 10,000 hectares of tank ecosystems

Conserving coastal mangroves and reintroducing stone spillways

Integrating traditional seasonal calendars with AI forecasts

Recognising Vedda knowledge of climate shifts as part of national risk strategy

Our past and future must align, or both will be lost.

A Global Destination for Resilient Tourism

Climate-conscious travelers increasingly seek safe, secure, and sustainable destinations. Under this policy, Sri Lanka will position itself as the world’s first “climate-safe sanctuary island” — a place where:

Resorts are cyclone- and tsunami-resilient

Tourists receive live hazard updates via mobile apps

World Heritage Sites are protected by environmental buffers

Visitors can witness tank restoration, ancient climate engineering, and modern AI in action

Sri Lanka will invite scientists, startups, and resilience investors to join our innovation ecosystem — building eco-tourism that’s disaster-proof by design.

Resilience as a National Identity

This shift is not just about floods or cyclones. It is about redefining our identity. To be Sri Lankan must mean to live in harmony with nature and to be ready for its changes. Our ancestors did it. The science now supports it. The time has come.

Let us turn Sri Lanka into the world’s first climate-resilient heritage island — where ancient wisdom meets cutting-edge science, and every citizen stands protected under one shield: a disaster-proof nation.

Features

The minstrel monk and Rafiki the old mandrill in The Lion King – I

Why is national identity so important for a people? AI provides us with an answer worth understanding critically (Caveat: Even AI wisdom should be subjected to the Buddha’s advice to the young Kalamas):

‘A strong sense of identity is crucial for a people as it fosters belonging, builds self-worth, guides behaviour, and provides resilience, allowing individuals to feel connected, make meaningful choices aligned with their values, and maintain mental well-being even amidst societal changes or challenges, acting as a foundation for individual and collective strength. It defines “who we are” culturally and personally, driving shared narratives, pride, political action, and healthier relationships by grounding people in common values, traditions, and a sense of purpose.’

Ethnic Sinhalese who form about 75% of the Sri Lankan population have such a unique identity secured by the binding medium of their Buddhist faith. It is significant that 93% of them still remain Buddhist (according to 2024 statistics/wikipedia), professing Theravada Buddhism, after four and a half centuries of coercive Christianising European occupation that ended in 1948. The Sinhalese are a unique ancient island people with a 2500 year long recorded history, their own language and country, and their deeply evolved Buddhist cultural identity.

Buddhism can be defined, rather paradoxically, as a non-religious religion, an eminently practical ethical-philosophy based on mind cultivation, wisdom and universal compassion. It is an ethico-spiritual value system that prioritises human reason and unaided (i.e., unassisted by any divine or supernatural intervention) escape from suffering through self-realisation. Sri Lanka’s benignly dominant Buddhist socio-cultural background naturally allows unrestricted freedom of religion, belief or non-belief for all its citizens, and makes the country a safe spiritual haven for them. The island’s Buddha Sasana (Dispensation of the Buddha) is the inalienable civilisational treasure that our ancestors of two and a half millennia have bequeathed to us. It is this enduring basis of our identity as a nation which bestows on us the personal and societal benefits of inestimable value mentioned in the AI summary given at the beginning of this essay.

It was this inherent national identity that the Sri Lankan contestant at the 72nd Miss World 2025 pageant held in Hyderabad, India, in May last year, Anudi Gunasekera, proudly showcased before the world, during her initial self-introduction. She started off with a verse from the Dhammapada (a Pali Buddhist text), which she explained as meaning “Refrain from all evil and cultivate good”. She declared, “And I believe that’s my purpose in life”. Anudi also mentioned that Sri Lanka had gone through a lot “from conflicts to natural disasters, pandemics, economic crises….”, adding, “and yet, my people remain hopeful, strong, and resilient….”.

“Ayubowan! I am Anudi Gunasekera from Sri Lanka. It is with immense pride that I represent my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka.

“I come from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka’s first capital, and UNESCO World Heritage site, with its history and its legacy of sacred monuments and stupas…….”.

The “inspiring words” that Anudi quoted are from the Dhammapada (Verse 183), which runs, in English translation: “To avoid all evil/To cultivate good/and to cleanse one’s mind -/this is the teaching of the Buddhas”. That verse is so significant because it defines the basic ‘teaching of the Buddhas’ (i.e., Buddha Sasana; this is how Walpole Rahula Thera defines Buddha Sasana in his celebrated introduction to Buddhism ‘What the Buddha Taught’ first published in1959).

Twenty-five year old Anudi Gunasekera is an alumna of the University of Kelaniya, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in International Studies. She is planning to do a Master’s in the same field. Her ambition is to join the foreign service in Sri Lanka. Gen Z’er Anudi is already actively engaged in social service. The Saheli Foundation is her own initiative launched to address period poverty (i.e., lack of access to proper sanitation facilities, hygiene and health education, etc.) especially among women and post-puberty girls of low-income classes in rural and urban Sri Lanka.

Young Anudi is primarily inspired by her patriotic devotion to ‘my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka’. In post-independence Sri Lanka, thousands of young men and women of her age have constantly dedicated themselves, oftentimes making the supreme sacrifice, motivated by a sense of national identity, by the thought ‘This is our beloved Motherland, these are our beloved people’.

The rescue and recovery of Sri Lanka from the evil aftermath of a decade of subversive ‘Aragalaya’ mayhem is waiting to be achieved, in every sphere of national engagement, including, for example, economics, communications, culture and politics, by the enlightened Anudi Gunasekeras and their male counterparts of the Gen Z, but not by the demented old stragglers lingering in the political arena listening to the unnerving rattle of “Time’s winged chariot hurrying near”, nor by the baila blaring monks at propaganda rallies.

Politically active monks (Buddhist bhikkhus) are only a handful out of the Maha Sangha (the general body of Buddhist bhikkhus) in Sri Lanka, who numbered just over 42,000 in 2024. The vast majority of monks spend their time quietly attending to their monastic duties. Buddhism upholds social and emotional virtues such as universal compassion, empathy, tolerance and forgiveness that protect a society from the evils of tribalism, religious bigotry and death-dealing religious piety.

Not all monks who express or promote political opinions should be censured. I choose to condemn only those few monks who abuse the yellow robe as a shield in their narrow partisan politics. I cannot bring myself to disapprove of the many socially active monks, who are articulating the genuine problems that the Buddha Sasana is facing today. The two bhikkhus who are the most despised monks in the commercial media these days are Galaboda-aththe Gnanasara and Ampitiye Sumanaratana Theras. They have a problem with their mood swings. They have long been whistleblowers trying to raise awareness respectively, about spreading religious fundamentalism, especially, violent Islamic Jihadism, in the country and about the vandalising of the Buddhist archaeological heritage sites of the north and east provinces. The two middle-aged monks (Gnanasara and Sumanaratana) belong to this respectable category. Though they are relentlessly attacked in the social media or hardly given any positive coverage of the service they are doing, they do nothing more than try to persuade the rulers to take appropriate action to resolve those problems while not trespassing on the rights of people of other faiths.

These monks have to rely on lay political leaders to do the needful, without themselves taking part in sectarian politics in the manner of ordinary members of the secular society. Their generally demonised social image is due, in my opinion, to three main reasons among others: 1) spreading misinformation and disinformation about them by those who do not like what they are saying and doing, 2) their own lack of verbal restraint, and 3) their being virtually abandoned to the wolves by the temporal and spiritual authorities.

(To be continued)

By Rohana R. Wasala ✍️

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result of this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoEnvironmentalists warn Sri Lanka’s ecological safeguards are failing

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDigambaram draws a broad brush canvas of SL’s existing political situation