Features

Jaishankar means Victory of Lord Shiva! – Part II

By Austin Fernando

(Former High Commissioner of Sri Lanka in India)

(Continuied from yesterday)

Development and relationships

Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena and his Indian counterpart Dr. S. Jaishankar considered developing mutual relationships concerning existing projects, e. g. the East Container Terminal (ECT) and the Trincomalee Petroleum Tanks.

The Indians have observed increasing involvement of the Chinese in the Colombo and Hambantota ports; in Colombo through the Colombo International Container Terminals Ltd – (CICT), a joint venture between China Merchants Port Holdings Company Ltd., and the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA). The main stakeholders of South Asia Gateway Terminal – (SAGT) are A.P. Moller Group and John Keells Holdings PLC. The CICT Transshipment business has been there since 2013 with the Chinese owning 85% of its shares; the SAGT has been operational with 10 partners since 1999, with 85% ownership. Therefore, it is only natural that the Indians seek the same terms as China and the private sector.

Transshipment and ‘Sale’ of ECT

India accounts for 66% of Colombo’s transshipment; it is projected to become the world’s fifth-biggest economy. Hence, Sri Lanka’s transshipment business may heavily depend on India. The argument being peddled in some quarters that a possible Indian policy decision to avoid Colombo could deal a crippling blow to Sri Lanka’s transshipment business has been rejected by the protesting trade unions, which insist that vital decisions in this regard are taken by shipping companies, and not governments. I believe the unions are right to a considerable extent on this score.

The transshipment business involves a complex integrated network of industrialists, shippers, ports, and a market that demands fast, timely, secured goods transfer at competitive prices, and, most of all, sustainability. For these reasons, reputed foreign shipping companies engaging with the SLPA, is welcome. As it happens elsewhere, it could be a joint venture (JV). The ‘sale’ of any physical assets is out of the question because the term ‘sale’ triggers protests.

Perhaps, the fact that Adani is an Indian venture might have ignited protests. The Indians may be questioning why such protests were absent when the CICT (with 85% shares against the proposed 51% for Adani) and the SAGT similarly partnered with the SLPA. Of course, the term ‘sale’ was not used then. Secondly, the Indians may be wondering why there was no hostile reaction to questionable actions benefitting the Chinese, e.g., the alienation of extremely valuable land for the Chinese, and permission for Chinese submarines to be berthed at the CICT, allegedly at a risk to the country’s sovereignty. Thirdly, due to other geopolitical contradictions, India may be suspecting that anti-Indian competitive business interests find expression through protesters, despite claims to the contrary. Fourthly, the Indians are concerned about not an only port-related business but also politics, defence, security, and self-respect.

Sri Lanka must strive to strengthen economic ties with India, whose economy is expanding fast. Therefore, transshipment networking should be re-evaluated in that context. Transshipment competitors such as Singapore, Malaysia, Dubai, Oman, Abu Dhabi, etc. have gone into overdrive in developing their ports. If Sri Lanka does not do likewise to remain competitive by developing its ports, it will lose.

As for the importance of upgrading ports, one can look at Abu Dhabi’s Khalifa Port. It handled around 2.5 million 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs) of cargo in 2018 and expects to increase the volume to 8 million-plus TEUs by 2023, by the addition of more ship-to-shore cranes and deeper berths. The investment of $ 1.1 billion comes from the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC). Another example is the Port of Salalah benefitting from over USD 800 million in investment expecting to handle over 5 million TEUs. Therefore, the Sri Lankan government must look for lessons on suitable partner/s.

Terminal operations are complex even in India. Although most Indian ports are state-owned, individual terminals are operated by large private companies such as DP World, AP Moller Terminals, and PSA International. Sri Lankans are demanding that ports be managed by the state when competitors are opening doors to foreign and local private partners. Given the generally poor performance of our state-owned ventures, the demand for state involvement in operating in a highly competitive environment must be gladdening the hearts of private competitors elsewhere and even here.

To understand the advantages of integrated terminal management I quote Rohan Masakorala. Having explained how shipping partners negotiate and undertake sharing assets, he has said:

“Therefore, it is proven beyond doubt that irrespective of the country’s wealth and the size of the shipping line, they do partner with competing lines for logical reasons as networks, provide better business models and solutions than working in isolation.”

We are not a large goods producer or shipowner. We must depend on ‘partnering with competing lines for logical reasons,’ utilizing favorable logistics networks, providing “better business models and solutions than working in isolation.” Thus, the challenge before Dr. Jaishankar may be to find a mutually agreeable business model. Probably, the managerial structures may be of some help, but They should have been transparently negotiated with all stakeholders.

Protesting India or JV concept?

Are the ongoing protests against India, or the proposed ECT deal? Or are they due to domestic political frustration or an attempt by the mainstream/social media to embarrass the government? Or are they to finally withdraw and show the hierarchy was reasonable? Is it to force withdrawal and antagonize India to make China to be the saviour from other economic problems? So many complications! Whatever, the protests are huge even to change stances.

Some of those who protested then are now ministers who have realized the need to address realities of development, geopolitics, diplomacy, neighbourly relations, other anticipated economic and political favours, etc; they support President Gotabaya Rajapaksa on the ECT issue. Similarly, some of those who were in the Yahapalana administration supporting the ECT deal is now in the Opposition, protesting the Indian involvement. They have forgotten that their government initiated this project with the Indians. The protesters need to take cognizance of the un-explained truth of mutuality as mentioned by Dr. Jaishankar.

Facing issues for solving

For decisions, clarity is needed on issues. There are six major issues”.

The first is the conceptual agreement of developing the terminals with foreign involvement. The Chandrika Kumaratunga and Mahinda Rajapaksa governments by establishing the SAGT and the CICT respectively accepted it. The incumbent President has realized this, but the circumstances have changed.

Chronologically, the Yahapalana government had only a terminal in mind when the MOU-2017 was signed. In 2018, President Sirisena insisted that the ECT be developed by the SLPA as currently demanded by Unions. He was for foreign participation in developing the West Container Terminal (WCT). In 2019, a Memorandum of Cooperation (MOC) was signed after President Sirisena’s discussions with PMs Modi and Abe for ECT development by an Indian and Japanese operational JV. About a fortnight back President Gotabaya Rajapaksa preferred developing WCT by the SLPA and ECT by Indians. The latest is the Unions accepting external investment in WCT, and the government developing the ECT. (The Island February 1st, 2021). Note the sea changes the wavering state policy on this issue has undergone during the last years and even within a fortnight.

The WCT was on offer in 2018 and the Indians refused. Will they change their stance now? It is too early for the Indians to respond to the latter. If they have stronger bargaining chips, they will remain tight-lipped with a view to winning finally. Anyhow, in inter-state business, if such a change happens, parties discuss and agree before making public statements. In a way, Sri Lanka, which withdrawn from the UNHRC resolution as publicised, withdrawal from a MOC will be no issue. It will depend on the chip in Indian hands.

Still do do not be surprised if the Indians strictly demand implementing the MoC.

The second is the operational mechanism. The CICT is operated by a Chinese company. At the SAGT, the mechanism involves international and local private operators. Therefore, according to the precedent, the agreed mechanism is foreign private operators with the SLPA. But now, is it Adani Group or a different company or other like above Abu Dhabi ports? Or is it an SLPA-Private Sector Project? Could it be Adani’s allied domestic private sector? Many equations are possible.

The third is the selection process. Adani Group is the nominee of India. How Gautham Adani’s company was selected is unknown. If the CITC or the SAGT partners were selected by established procurement procedures, the precedent must be followed. One may recall that Minister Arjuna Ranatunga informed the Cabinet before 2017- MSC that the ‘new operator should be selected following the established Procurement Guidelines.’ Recently, Minister Namal Rajapaksa has also spoken of procedures. These must be discussed across the table because there could be exceptions to procedures.

The fourth is the ownership of the ECT project. The Presidential Media Unit (PMU) Statement and PM Rajapaksa’s statement in Parliament said: “No selling, no leasing of ECT’. But the PMU statement signified an “investment project that has 51% ownership by the government” and the remainder by Adani and other stakeholders. The term ‘51% ownership’ unfortunately but logically makes Adani and others the ‘owner of 49%.”

However, in the aforesaid MOC these percentages are for a “Terminal Operations Company,” meant for the “explicit purpose of providing the equipment and systems necessary for the development of the ECT and managing the ECT.” This difference between ‘ownership’ and the operational company’s objectives clear doubts, but this fact has not been highlighted, fertilizing suspicions.

Ownership is the legal relationship between a person and an object. Therefore, the protestors harp against giving ‘part-ownership’ to Adani, because SLPA owns the whole ECT now. The protestors understand “ownership” as an outcome of a ‘selling’ process. As damage controlling, the President repeated about a JV, with SLPA participation with Adani’s, and others as stakeholders. It is the reality matching the MOC. But the explanation came one week after the PMU statement. By then protestors have socially marketed ‘selling ECT.’

The fifth issue is the influencers/motivators. How views against the President’s wishes are being expressed smack of a move to keep the Indians away. Clearing such doubts is difficult when efforts are organized concertedly.

Sixthly, the happenings unrelated to the ECT could muddy the waters. The destruction of the Jaffna University memorial, Indian fishermen’s deaths, and the Cabinet decision to establish Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems in Nainathivu, Delft, and Analathivu islands through a Chinese contractor (upon international competitive bidding) are three such issues. The last is an extremely security-sensitive issue for India although it was presumably not a favor done to the Chinese by Sri Lanka. The Indians have previously vehemently protested the berthing of Chinese submarines in Colombo and the Chinese housing projects in the North. The Indian protests will be diplomatic and subtle. Nevertheless, their repercussions could override the ECT issues and may influence other bilateral and multilateral matters.

Way forward amidst contradictions

The need is to develop the ECT. Sri Lankan governments are known for policy changes and contradictions; Indians are different. Just see the aforesaid policy contradictions. Even the ECT protesters have double standards. When the CICT with ‘85% foreign ownership’ was established, there were no grudges. When the government announced its decision to form a JV with Adani and others, having 49% shares, therein to run the ECT all hell broke loose!

It is necessary to stop bickering if it is development that we seek. The country must prioritize the economy, neighborhood relations, private sector involvement, foreign investment promotion, diplomacy, security, financing, other personal and political issues.

Although decisions on the Sri Lankan ports must be economic, in this complex world, they are invariably influenced by other factors. I hope the government will strike a balance and select the best option. Sri Lankan must not enslave itself to other countries. It must negotiate for the best profitable and sustainable solutions, be it with China, India, or the US or with large shipping companies undertaking port development. The government must maintain transparency in negotiating the terms of port development. A move to sell a state asset or any move that can be construed as such is sure to lead to negative responses. Concurrently, let the protesters engage with the government and work toward developing the Colombo Port.

As it is, DR Jaishankar’s victory has not yet come about completely. There are roadblocks on his path. The Indian silence is deceptive. However, the Indian responses may not be restricted to shipping. When responses deceptively happen, the consequences could be hurting. Dr. Jaishankar knows Kautilyan deception and would have learned from Sun Tzu when he was the Indian Ambassador in China. Hence the need for Sri Lanka to tread cautiously.

Reciprocation of relationships

Nevertheless, the professional diplomat that he is, Minister Jaishankar highlighted the grand mutual relationship with Sri Lanka, the “trust, interest, respect, and sensitivity.” Perhaps, Indian critics could question this mutuality having seen the protests.

During the Yahapalana regime, mutuality on the part of India was diminishing, although India does not publicly admit it. This for example was reflected in the budgetary allocations for the neighborhood in Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s budget, where only INR 250 crore was provided for Sri Lanka out of INR 8,415 crore total, while countries like Bhutan, Nepal, Mauritius, the Maldives received much more. The reason may be the security considerations of India. India further expanded a package for the Maldives (August 13th, 2020), that included a $100 million grant and a $400 million new line of credit, for the Greater Malé Connectivity Project, expressing extra neighborly attachment.

Concurrently, requests for a $ 1 billion financial lifeline swap and nearly $ 1 billion debt moratorium made by President and PM Rajapaksas from PM Modi are delayed for months, irrespectively of the much-flaunted mutuality. Sri Lanka should read these signs carefully and understand the message.

Minister Gunawardena (understandably) did not mention competition that may arise from the seaport Projects at Vizhinjam in Kerala, and Nicobar, owned by Indians. Both did not bother about PM Modi’s declaration: “There is a proposal to build a transshipment port at Great Nicobar at a cost of about Rs. 10,000 crores. Large ships can dock once this port is ready” (The Times of India -Business- of August 10th, 2020). Mark the words, “transshipment port!” These ports will invariably compete with Colombo’s ETC in the future, and India may through Nicobar aim to become the transshipment hub, being in proximity to the busy east-west shipping routes. This points to the need for developing the ECT fast and making it competitive.

For sustainability and safety in this competitive business, it will be necessary to be cautious if joint ventures are to be formed, especially by reaching an agreement on time frames, exit clauses, investment programming, senior managerial positioning, arbitration in Sri Lanka, etc. For these the active participation of the SLPA, which has expertise is mandatory. Unfortunately, nothing is heard about such moves. One hears only the voice of the protesting Unions.

Security aspects of relationships

Dr. Jaishankar mentioned maritime security and safety but did not make specific mention of Quad or Indo-Pacific interventions or China. What we must understand about the Indian attitude towards security is that India expects us to be India-centric as could be seen from the following statement by Shri Avatar Singh Bhasin on Indian security relationships:

“There could be no running away from the fact that small states in the region fell in India’s security perimeter and therefore must not follow policies that would impinge on her security concerns in the area. They should not seek to invite outside power(s). If any one of them needed any assistance it should look to India. India’s attitude and relationship with her immediate neighbors depended on their appreciation of India’s regional security concerns; they would serve as buffer states in the event of an extra-regional threat and not proxies of the outside powers…”

The proxy need not be only China; even if it is the US, India will be perturbed, if lines are crossed. Therefore, Minister Jaishankar’s security concerns must be viewed concerning the aforesaid criteria. Dr. Jaishankar subscribes to these. About his visit, the Indian Television had this to say: “An important focus of his visit will be the Chinese presence in the Hambantota harbor on a 99-year lease. It is an understanding between China and Sri Lanka that they will not undertake any military venture there. So, India will take the help of Sri Lanka to ensure that Chinese military or Chinese hegemony don’t come to this region.” This is the Indian attitude.

India’s position always remains the same: “Do not be a proxy of the Chinese, be a buffer state! Do not allow the Indian Ocean to be the Chinese Ocean!” However, considering the proximity, long relations, the possibility for political displacements, regional economics, etc. Sri Lanka will think of the advantage of being with the Indians, of course, without being a buffer. To what extent other motivations—financial, economic development, diplomatic, security, etc.—would work is also important especially when Sri Lanka is haunted by international interventions like the one at the UNHRC. It is not easy to gain the required balance.

Conclusion

Indo-Lanka relations were highlighted by both Ministers. The impending global situations after COVID 19 and the complexities arising due to geopolitics and developments will compel Sri Lanka to work with the world powers. In that respect, even if the past is forgotten the present and future will make it imperative that we maintain friendly relations with everyone, especially with India and China, latter expected to be the future number one economy. This is the reason why Sri Lanka should pay attention to the purpose of Dr. Jaishankar’s recent visit and maintain balance.

Overall, the Indian Foreign Minister visited Sri Lankan not to lose, but to prove that he was ‘Jai Shankar.’ Whether he departed on January 7th, 2021 with expected goodies, officially satisfied to celebrate his 66th birthday the following day, are secrets and will be known in days to come.

Finally, it will be mutually beneficial for both Sri Lanka and India to make compromises and strengthen their relations instead of being obdurate.

Features

Ranking public services with AI — A roadmap to reviving institutions like SriLankan Airlines

Efficacy measures an organisation’s capacity to achieve its mission and intended outcomes under planned or optimal conditions. It differs from efficiency, which focuses on achieving objectives with minimal resources, and effectiveness, which evaluates results in real-world conditions. Today, modern AI tools, using publicly available data, enable objective assessment of the efficacy of Sri Lanka’s government institutions.

Among key public bodies, the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka emerges as the most efficacious, outperforming the Department of Inland Revenue, Sri Lanka Customs, the Election Commission, and Parliament. In the financial and regulatory sector, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) ranks highest, ahead of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Public Utilities Commission, the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission, the Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the Sri Lanka Standards Institution.

Among state-owned enterprises, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) leads in efficacy, followed by Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank. Other institutions assessed included the State Pharmaceuticals Corporation, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board, the Ceylon Electricity Board, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and the Sri Lanka Transport Board. At the lower end of the spectrum were Lanka Sathosa and Sri Lankan Airlines, highlighting a critical challenge for the national economy.

Sri Lankan Airlines, consistently ranked at the bottom, has long been a financial drain. Despite successive governments’ reform attempts, sustainable solutions remain elusive.

Globally, the most profitable airlines operate as highly integrated, technology-enabled ecosystems rather than as fragmented departments. Operations, finance, fleet management, route planning, engineering, marketing, and customer service are closely coordinated, sharing real-time data to maximise efficiency, safety, and profitability.

The challenge for Sri Lankan Airlines is structural. Its operations are fragmented, overly hierarchical, and poorly aligned. Simply replacing the CEO or senior leadership will not address these deep-seated weaknesses. What the airline needs is a cohesive, integrated organisational ecosystem that leverages technology for cross-functional planning and real-time decision-making.

The government must urgently consider restructuring Sri Lankan Airlines to encourage:

=Joint planning across operational divisions

=Data-driven, evidence-based decision-making

=Continuous cross-functional consultation

=Collaborative strategic decisions on route rationalisation, fleet renewal, partnerships, and cost management, rather than exclusive top-down mandates

Sustainable reform requires systemic change. Without modernised organisational structures, stronger accountability, and aligned incentives across divisions, financial recovery will remain out of reach. An integrated, performance-oriented model offers the most realistic path to operational efficiency and long-term viability.

Reforming loss-making institutions like Sri Lankan Airlines is not merely a matter of leadership change — it is a structural overhaul essential to ensuring these entities contribute productively to the national economy rather than remain perpetual burdens.

By Chula Goonasekera – Citizen Analyst

Features

Why Pi Day?

International Day of Mathematics falls tomorrow

The approximate value of Pi (π) is 3.14 in mathematics. Therefore, the day 14 March is celebrated as the Pi Day. In 2019, UNESCO proclaimed 14 March as the International Day of Mathematics.

Ancient Babylonians and Egyptians figured out that the circumference of a circle is slightly more than three times its diameter. But they could not come up with an exact value for this ratio although they knew that it is a constant. This constant was later named as π which is a letter in the Greek alphabet.

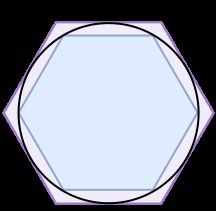

It was the Greek mathematician Archimedes (250 BC) who was able to find an upper bound and a lower bound for this constant. He drew a circle of diameter one unit and drew hexagons inside and outside the circle such that the sides of each hexagon touch the sides of the circle. In mathematics the circle passing through all vertices of a polygon is called a ‘circumcircle’ and the largest circle that fits inside a polygon tangent to all its sides is called an ‘incircle’. The total length of the smaller hexagon then becomes the lower bound of π and the length of the hexagon outside the circle is the upper bound. He realised that by increasing the number of sides of the polygon can make the bounds get closer to the value of Pi and increased the number of sides to 12,24,48 and 60. He argued that by increasing the number of sides will ultimately result in obtaining the original circle, thereby laying the foundation for the theory of limits. He ended up with the lower bound as 22/7 and the upper bound 223/71. He could not continue his research as his hometown Syracuse was invaded by Romans and was killed by one of the soldiers. His last words were ‘do not disturb my circles’, perhaps a reference to his continuing efforts to find the value of π to a greater accuracy.

Archimedes can be considered as the father of geometry. His contributions revolutionised geometry and his methods anticipated integral calculus. He invented the pulley and the hydraulic screw for drawing water from a well. He also discovered the law of hydrostatics. He formulated the law of levers which states that a smaller weight placed farther from a pivot can balance a much heavier weight closer to it. He famously said “Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the earth”.

Mathematicians have found many expressions for π as a sum of infinite series that converge to its value. One such famous series is the Leibniz Series found in 1674 by the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, which is given below.

π = 4 ( 1 – 1/3 + 1/5 – 1/7 + 1/9 – ………….)

The Indian mathematical genius Ramanujan came up with a magnificent formula in 1910. The short form of the formula is as follows.

π = 9801/(1103 √8)

For practical applications an approximation is sufficient. Even NASA uses only the approximation 3.141592653589793 for its interplanetary navigation calculations.

It is not just an interesting and curious number. It is used for calculations in navigation, encryption, space exploration, video game development and even in medicine. As π is fundamental to spherical geometry, it is at the heart of positioning systems in GPS navigations. It also contributes significantly to cybersecurity. As it is an irrational number it is an excellent foundation for generating randomness required in encryption and securing communications. In the medical field, it helps to calculate blood flow rates and pressure differentials. In diagnostic tools such as CT scans and MRI, pi is an important component in mathematical algorithms and signal processing techniques.

This elegant, never-ending number demonstrates how mathematics transforms into practical applications that shape our world. The possibilities of what it can do are infinite as the number itself. It has become a symbol of beauty and complexity in mathematics. “It matters little who first arrives at an idea, rather what is significant is how far that idea can go.” said Sophie Germain.

Mathematics fans are intrigued by this irrational number and attempt to calculate it as far as they can. In March 2022, Emma Haruka Iwao of Japan calculated it to 100 trillion decimal places in Google Cloud. It had taken 157 days. The Guinness World Record for reciting the number from memory is held by Rajveer Meena of India for 70000 decimal places over 10 hours.

Happy Pi Day!

The author is a senior examiner of the International Baccalaureate in the UK and an educational consultant at the Overseas School of Colombo.

by R N A de Silva

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoHeat Index at ‘Caution Level’ in the Sabaragamuwa province and, Colombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Hambanthota and Monaragala districts

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe final voyage of the Iranian warship sunk by the US