Features

Irrepressible Julia Margaret Cameron at peace in Bogawantalawa

By GEORGE BRAINE

Some years ago, my sister, BIL, and I drove to the Dimbula area, visiting Anglican churches and graveyards looking for evidence of our ancestors. At the quaint St. Mary’s church, Bogawantalawa, we found the grave of my grand uncle, Frank Wyndham Becher Braine, who died on March 9, 1879, at only 11 months. We may have been the first family members to visit his grave in more than a 100 years.

That graveyard is also the resting place of a husband and wife, Charles Hay and Julia Margaret Cameron. Julia, during and after her lifetime, has been described as “indefatigable”, “a centripetal force”, “a bully”, “queenly”, “a one-woman empire”, “infernal”, “hot to handle”, “omnipresent”, “a tigress”. She was “impatient and restive”, for whom “a single lifetime wasn’t enough”. Who was this remarkable Victorian?

Julia was born in Calcutta, in 1815, one of seven daughters of James Pattle of the Indian Civil Service. They belonged to the Anglo-Indian upper class, and were all sent to France – their mother Adeline Marie was of the French aristocracy – for their education. The sisters were well accomplished and known for their “charm, wit, and beauty”, and “unconventional behaviour and dress”: they conversed among themselves in Hindustani, even in England. They served curry. They all married well, four spouses being fellow Anglo-Indians in the civil service and military.

Julia lived at various times in England, France, back in India, South Africa, in India again, on the Isle of Wight, and finally in Ceylon. Travel to Cape Town in 1835 was for her health, after recovering from serious illnesses. Charles Hay Cameron, a distinguished legal scholar from Calcutta, was also in Cape Town, perhaps after a severe bout of malaria. They met, and married back in Calcutta in 1838. Charles was 20 years her senior. Together, they raised 11 children, five of their own and the rest adopted.

Julia’s introduction to London’s artistic and cultural milieu came in 1845, at her sister Sara Prinsep’s residence in Kensington. Sara conducted a salon at home where poets, artists, writers and philosophers such as Tennyson, Rossetti, the Brownings, Longfellow, Trollope, Darwin, Thackeray, Henry Taylor, du Maurier and Leighton were regular attendees. Julia’s “hero worship” of these luminaries began at that time.

“Dimbola”

In 1860, the Camerons moved to the Isle of Wight, to a home named “Dimbola”, obviously after Dimbula in Ceylon, where Charles Cameron had invested in vast coffee and rubber plantations. He had served on the Colebrooke-Cameron Commission (appointed in 1833) to assess the administration of Ceylon and make recommendations for administrative, financial, economic, and judicial reform. The poet Henry Taylor, a close friend of Julia, wrote that Charles had “a passionate love for the island [and] he never ceased to yearn after the island as his place of abode”.

Incidentally, an English planter, named Herbert Brett, known to my family, named his British home “Yakvilla”. He had once been the manager of Yakwila Estate, near Pannala in the NWP.

“Dimbola” had been purchased because it was next door to Tennyson’s home, and a private gate connected the two properties. Better known as Alfred Lord Tennyson, he had become Britain’s Poet Laureate by then. Julia and the poet addressed each other by their first names. When he refused to be vaccinated against smallpox, Julia supposedly went to his home and yelled at him: “You’re a coward, Alfred, a coward!”

Soon, the Cameron and Tennyson families began entertaining well-known visitors to the Poet Laureate with music, poetry readings, and amateur plays, creating an artistic ambience similar to that seen earlier at Sara Princep’s home in Kensington. in keeping with Julia’s personality, the activities could be indefatigable. “Mrs. Cameron seemed to be omnipresent—organising happy things, summoning one person and another, ordering all the day and long into the night, for of an evening came impromptu plays and waltzes in the wooden ballroom, and young partners dancing under the stars”, wrote Anne Thackeray, the novelist’s daughter. Even Julia’s generosity could be overwhelming. Henry Taylor expressed this best: “she keeps showering upon us her ‘barbaric pearls and gold,’—India shawls, turquoise bracelets, inlaid portfolios, ivory elephants”.

Photography

A turning point in Julia’s life came in 1863, when she was already 48. Charles was in Ceylon, and Julia was bored. A daughter gifted her a camera to keep her “amused”. A clumsy affair in those early days of photography, it consisted of two wooden boxes, bound in brass, one of which slid inside the other, with a single focus lens. The timber tripod was unwieldy. Images were recorded on a heavy, rectangular glass plate measuring 11 x 9 inches.

Julia took to photography with her usual energy and enthusiasm, converting a chicken coop to a studio. If the camera was clumsy, the process of photo development was even more complicated and challenging, with the use of chemicals – collodion, silver nitrate, potassium cyanide, gold chloride (even egg white was used) – and the need to work quickly. Julia’s hands and clothes are said to have become black and brown with the chemicals. The process was riven with trial and error.

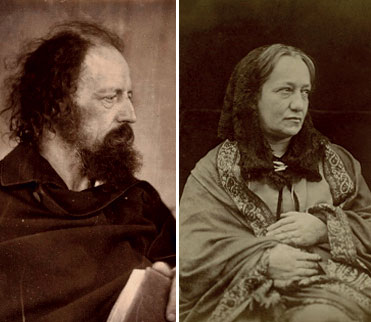

Julia managed to coerce illustrious visitors to Tennyson’s home to pose for her. They included Longfellow, Trollope, Darwin, John Herschel, Robert Browning, the painter George Watts, Thackeray, Carlyle, and Lewis Carrol, and Tennyson, of course. Her photograph of Tennyson is shown on this page. The men were photographed in pensive moods, intended to capture their “genius”. She also photographed women for their beauty, and children as “innocent, kind, and noble”, a prevailing Victorian notion.

Posing for a portrait was no easy task: the subject had to be within eight feet of the camera, and had to remain still for around 10 minutes. Julia chose not to use head supports. Here is a vivid description of a photographic session with Julia: “The studio, I remember, was very untidy and very uncomfortable. Mrs. Cameron put a crown on my head and posed me as the heroic queen. … The exposure began. A minute went over and I felt as if I must scream, another minute and the sensation was as if my eyes were coming out of my head … a fifth—but here I utterly broke down …” No wonder Tennyson called Julia’s sitters “victims”.

Showing sound business acumen, Julia copyrighted, published, exhibited and marketed her work. Harper’s Weekly, writing on a London exhibition in 1870, noted that “many art critics to go into raptures over [Julia’s] work as something beyond the range of ordinary photographic achievement”.

For the sake of brevity, I have focused on her portraits. She also photographed individuals and groups of people depicting allegories, religion, and literature; illustrations for Tennyson’s Idylls of the King being especially noteworthy. In Ceylon, her subjects were mainly ordinary people and plantation workers. Her career wasn’t long – only 12 years – and despite criticism of her work for technical imperfections and the numerous challenges she faced, Julia produced about 900 photographs. An incredible feat.

To Ceylon

From the early 1840s, Charles had bought up sprawling extents of land at Ceylon at bargain prices, and the 1850s and 60s were the best years for coffee. But in addition to being absentee landlords, the Camerons faced other problems: extremes of weather, a shortage of labour, transporting the coffee to Colombo on poor roads, incompetent managers, and the devastating coffee blight.

Charles was in poor health – “receiving visitors in his bedroom or walking about the garden reciting Homer and Virgil” – and had not worked since 1848, and the expenses of supporting a large family and their lifestyle at “Dimbola” had forced the Camerons to borrow heavily. In 1864, Charles admitted to being virtually “penniless”.

Charles was keen to move to Ceylon, but Julia was not. Attempting to change her mind, he wrote her a moving, lyrical description of his “Swiss cottage” bungalow and the surrounding plantations in Ceylon. In Ceylon, the cost of living would be cheaper, and he was confident that his health would improve. Later, Julia wrote that Charles’ passion for his Ceylon properties had “weakened his love for England”. Lord Overstone, their main creditor, was pressuring them to sell Rathoongodde (Rahathungoda), their plantation in the Deltota area managed by son Ewen.

Finally, Julia gave in partly because four of their sons were already in Ceylon. Charles’ health is said to have magically improved. In 1875, when she was 60 years old and Charles was 80, they left “Dimbola” for Ceylon, taking a maid, a cow, Julia’s photographic equipment, and two coffins, packed with china and glass. Henry Taylor noted that they had departed for Ceylon “to live and die” there, and that Charles had “never ceased to yearn after the island as his place of abode”.

Their son, Hardinge, the Governor’s private secretary, owned a bungalow on the river at Kalutara, on the western coast. Julia and Charles divided their time in Ceylon between Kalutara and their plantations in the hill country. Julia soon fell under Ceylon’s spell, writing that “the glorious beauty of the scenery — the primitive simplicity of the inhabitants and the charms of the climate all make me love Ceylon more and more”.

When the botanical painter Marianne North visited the Camerons at Kalutara, Julia went into a “fever of excitement” at having found a European subject. She dressed North up “in flowing draperies of cashmere wool” (despite the intense heat), with “spiky coconut branches running into [her] head” to be photographed. A remarkable photo taken by Julia shows North standing at her easel on the spacious verandah of the Kalutara house, with a bare-bodied “native” holding a clay pot over his shoulder.

Julia must have been busy during this period, because North noted that “the walls of the room were covered with magnificent photographs; others were tumbling about the tables, chairs, and floors”. But, only about 30 photographs from Julia’s Ceylon period have survived. The architect Ismeth Raheem, who has conducted extensive research on Julia, has stated that some photographs given to the Colombo Museum appear to be lost. No surprise there.

After a six month visit to England, Julia developed a dangerous chill (pneumonia?) upon her return to Ceylon. She died on 26 January 1879 at Glencairn Estate. Charles and four of her sons were with her. Her coffin was drawn by white bulls and also carried by plantation workers to St. Mary’s.

Back to the Braines

My great, great grandfather, Charles Joseph Braine, arrived in Ceylon in 1862, as the manager of Ceylon Company, which I believe is the predecessor of Ceylon Tea Plantations Company. By 1880, he is listed as the first owner of Abbotsleigh Estate in Hatton. (In contrast with Charles Cameron and Herbert Brett, who named their homes in England after plantations in Ceylon, Charles Joseph named his plantation in Ceylon after his property, Abbotsleigh, in England.)

The Camerons arrived in Ceylon in 1875. British planters, away from home and often stationed in remote plantations, socialised mainly at two locations: their clubs, and at church. I have no doubt that Charles Joseph Braine and the Camerons had met at the club, perhaps even during Charles’ previous visits to his plantations, and at church.

St. Mary’s Church, Bogawantalawa, was dedicated in 1877. Although Charles Cameron wasn’t religious and did not attend church, Julia did, traveling perhaps on horseback or bullock cart like the families of fellow planters. The Camerons gifted three stained glass windows to St. Mary’s, and that is obviously where Julia worshipped and wished to be buried.

Charles Joseph’s son, Charles Frederick Braine (my great grandfather) arrived in Ceylon in 1869, at 19 years of age, six years before the Camerons did, and worked at Meddecombra Estate in the Dimbula area. Later, he was the manager of the vast Wanarajah Estate. He, too, may have met Charles and later Julia Cameron. Braine must have worshipped at St. Mary’s, because, as I stated at the beginning of this article, his infant son was buried at St. Mary’s churchyard in March, 1879, only two months after Julia was buried there.

My grandfather, Charles Stanley, was born in Ceylon in 1874, and, as a child, is likely have met the Camerons, or at least Julia, at church. He had an angelic appearance in early photographs, and I like to imagine Julia tousling his hair! Hence, although no records exist, three generations of my ancestors are likely to have been acquainted with the Camerons, and perhaps worshipped alongside her at St. Mary’s.

The legacy of the Camerons

Julia Margaret Cameron is acknowledged now as one of the most important portraitists of the 19th century. Her work has been exhibited in important galleries and museums in the UK, the USA, Japan, and elsewhere. The photographer Stephen White, who calls Julia a “revered figure” in the history of photography, wrote in 2020 that an album of Julia’s photographs was valued at £3 million. Each of her prints are said to be worth about $50,000.

The Cameron home on the Isle of Wight, “Dimbola”, is now owned by the Julia Margaret Cameron Trust, and consists of a museum and galleries. It has a growing permanent collection of Julia’s photographs, and is dedicated to her life and work.

When I visited St. Mary’s Church in 2012, looking for evidence of my ancestors, the churchyard was covered in weeds. Stephen White, who visited St. Mary’s Church in 2017, lamented that the grave of “a woman whose photographs still stirred thousands with their beauty, and whose name was spoken with reverence by lovers of photography around Europe and the States” could be so “forlorn … unattended [and] unadorned”.

A photograph of the grave that accompanies his article indeed shows a neglected gravesite, the curb cracked. The more recent photo shown here, from the Thuppahi’s blog, shows a better maintained grave. Ismeth Raheem wrote that the house on Glencairn Estate where Julia died had been demolished in 2021.

While Julia is the better known of the Camerons, Charles made a lasting impact on Ceylon as a member of the Colebrooke-Cameron Commission, which, among other contributions, provided a uniform code of justice for the island. His on and off association with Ceylon was much longer, about 50 years at the time he died. A romantic at heart, he loved Ceylon with a passion.Recently, Ismeth Raheem and Dr. Martin Pieris have brought out a short film, “From the Isle of Wight to Ceylon”, based on substantial research on Julia’s life. Finally, in Sri Lanka, Julia Margaret Cameron appears to be receiving the recognition she fully deserves.

Features

Disaster-proofing paradise: Sri Lanka’s new path to global resilience

iyadasa Advisor to the Ministry of Science & Technology and a Board of Directors of Sri Lanka Atomic Energy Regulatory Council A value chain management consultant to www.vivonta.lk

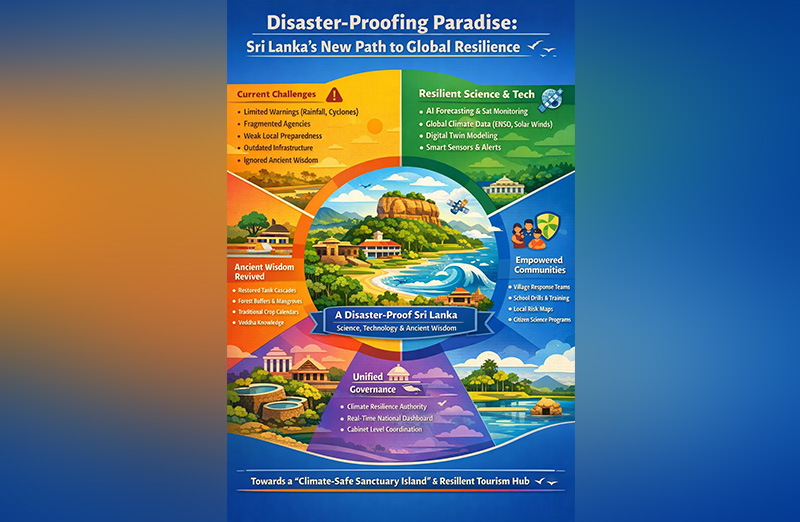

As climate shocks multiply worldwide from unseasonal droughts and flash floods to cyclones that now carry unpredictable fury Sri Lanka, long known for its lush biodiversity and heritage, stands at a crossroads. We can either remain locked in a reactive cycle of warnings and recovery, or boldly transform into the world’s first disaster-proof tropical nation — a secure haven for citizens and a trusted destination for global travelers.

The Presidential declaration to transition within one year from a limited, rainfall-and-cyclone-dependent warning system to a full-spectrum, science-enabled resilience model is not only historic — it’s urgent. This policy shift marks the beginning of a new era: one where nature, technology, ancient wisdom, and community preparedness work in harmony to protect every Sri Lankan village and every visiting tourist.

The Current System’s Fatal Gaps

Today, Sri Lanka’s disaster management system is dangerously underpowered for the accelerating climate era. Our primary reliance is on monsoon rainfall tracking and cyclone alerts — helpful, but inadequate in the face of multi-hazard threats such as flash floods, landslides, droughts, lightning storms, and urban inundation.

Institutions are fragmented; responsibilities crisscross between agencies, often with unclear mandates and slow decision cycles. Community-level preparedness is minimal — nearly half of households lack basic knowledge on what to do when a disaster strikes. Infrastructure in key regions is outdated, with urban drains, tank sluices, and bunds built for rainfall patterns of the 1960s, not today’s intense cloudbursts or sea-level rise.

Critically, Sri Lanka is not yet integrated with global planetary systems — solar winds, El Niño cycles, Indian Ocean Dipole shifts — despite clear evidence that these invisible climate forces shape our rainfall, storm intensity, and drought rhythms. Worse, we have lost touch with our ancestral systems of environmental management — from tank cascades to forest sanctuaries — that sustained this island for over two millennia.

This system, in short, is outdated, siloed, and reactive. And it must change.

A New Vision for Disaster-Proof Sri Lanka

Under the new policy shift, Sri Lanka will adopt a complete resilience architecture that transforms climate disaster prevention into a national development strategy. This system rests on five interlinked pillars:

Science and Predictive Intelligence

We will move beyond surface-level forecasting. A new national climate intelligence platform will integrate:

AI-driven pattern recognition of rainfall and flood events

Global data from solar activity, ocean oscillations (ENSO, MJO, IOD)

High-resolution digital twins of floodplains and cities

Real-time satellite feeds on cyclone trajectory and ocean heat

The adverse impacts of global warming—such as sea-level rise, the proliferation of pests and diseases affecting human health and food production, and the change of functionality of chlorophyll—must be systematically captured, rigorously analysed, and addressed through proactive, advance decision-making.

This fusion of local and global data will allow days to weeks of anticipatory action, rather than hours of late alerts.

Advanced Technology and Early Warning Infrastructure

Cell-broadcast alerts in all three national languages, expanded weather radar, flood-sensing drones, and tsunami-resilient siren networks will be deployed. Community-level sensors in key river basins and tanks will monitor and report in real-time. Infrastructure projects will now embed climate-risk metrics — from cyclone-proof buildings to sea-level-ready roads.

Governance Overhaul

A new centralised authority — Sri Lanka Climate & Earth Systems Resilience Authority — will consolidate environmental, meteorological, Geological, hydrological, and disaster functions. It will report directly to the Cabinet with a real-time national dashboard. District Disaster Units will be upgraded with GN-level digital coordination. Climate literacy will be declared a national priority.

People Power and Community Preparedness

We will train 25,000 village-level disaster wardens and first responders. Schools will run annual drills for floods, cyclones, tsunamis and landslides. Every community will map its local hazard zones and co-create its own resilience plan. A national climate citizenship programme will reward youth and civil organisations contributing to early warning systems, reforestation (riverbank, slopy land and catchment areas) , or tech solutions.

Reviving Ancient Ecological Wisdom

Sri Lanka’s ancestors engineered tank cascades that regulated floods, stored water, and cooled microclimates. Forest belts protected valleys; sacred groves were biodiversity reservoirs. This policy revives those systems:

Restoring 10,000 hectares of tank ecosystems

Conserving coastal mangroves and reintroducing stone spillways

Integrating traditional seasonal calendars with AI forecasts

Recognising Vedda knowledge of climate shifts as part of national risk strategy

Our past and future must align, or both will be lost.

A Global Destination for Resilient Tourism

Climate-conscious travelers increasingly seek safe, secure, and sustainable destinations. Under this policy, Sri Lanka will position itself as the world’s first “climate-safe sanctuary island” — a place where:

Resorts are cyclone- and tsunami-resilient

Tourists receive live hazard updates via mobile apps

World Heritage Sites are protected by environmental buffers

Visitors can witness tank restoration, ancient climate engineering, and modern AI in action

Sri Lanka will invite scientists, startups, and resilience investors to join our innovation ecosystem — building eco-tourism that’s disaster-proof by design.

Resilience as a National Identity

This shift is not just about floods or cyclones. It is about redefining our identity. To be Sri Lankan must mean to live in harmony with nature and to be ready for its changes. Our ancestors did it. The science now supports it. The time has come.

Let us turn Sri Lanka into the world’s first climate-resilient heritage island — where ancient wisdom meets cutting-edge science, and every citizen stands protected under one shield: a disaster-proof nation.

Features

The minstrel monk and Rafiki the old mandrill in The Lion King – I

Why is national identity so important for a people? AI provides us with an answer worth understanding critically (Caveat: Even AI wisdom should be subjected to the Buddha’s advice to the young Kalamas):

‘A strong sense of identity is crucial for a people as it fosters belonging, builds self-worth, guides behaviour, and provides resilience, allowing individuals to feel connected, make meaningful choices aligned with their values, and maintain mental well-being even amidst societal changes or challenges, acting as a foundation for individual and collective strength. It defines “who we are” culturally and personally, driving shared narratives, pride, political action, and healthier relationships by grounding people in common values, traditions, and a sense of purpose.’

Ethnic Sinhalese who form about 75% of the Sri Lankan population have such a unique identity secured by the binding medium of their Buddhist faith. It is significant that 93% of them still remain Buddhist (according to 2024 statistics/wikipedia), professing Theravada Buddhism, after four and a half centuries of coercive Christianising European occupation that ended in 1948. The Sinhalese are a unique ancient island people with a 2500 year long recorded history, their own language and country, and their deeply evolved Buddhist cultural identity.

Buddhism can be defined, rather paradoxically, as a non-religious religion, an eminently practical ethical-philosophy based on mind cultivation, wisdom and universal compassion. It is an ethico-spiritual value system that prioritises human reason and unaided (i.e., unassisted by any divine or supernatural intervention) escape from suffering through self-realisation. Sri Lanka’s benignly dominant Buddhist socio-cultural background naturally allows unrestricted freedom of religion, belief or non-belief for all its citizens, and makes the country a safe spiritual haven for them. The island’s Buddha Sasana (Dispensation of the Buddha) is the inalienable civilisational treasure that our ancestors of two and a half millennia have bequeathed to us. It is this enduring basis of our identity as a nation which bestows on us the personal and societal benefits of inestimable value mentioned in the AI summary given at the beginning of this essay.

It was this inherent national identity that the Sri Lankan contestant at the 72nd Miss World 2025 pageant held in Hyderabad, India, in May last year, Anudi Gunasekera, proudly showcased before the world, during her initial self-introduction. She started off with a verse from the Dhammapada (a Pali Buddhist text), which she explained as meaning “Refrain from all evil and cultivate good”. She declared, “And I believe that’s my purpose in life”. Anudi also mentioned that Sri Lanka had gone through a lot “from conflicts to natural disasters, pandemics, economic crises….”, adding, “and yet, my people remain hopeful, strong, and resilient….”.

“Ayubowan! I am Anudi Gunasekera from Sri Lanka. It is with immense pride that I represent my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka.

“I come from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka’s first capital, and UNESCO World Heritage site, with its history and its legacy of sacred monuments and stupas…….”.

The “inspiring words” that Anudi quoted are from the Dhammapada (Verse 183), which runs, in English translation: “To avoid all evil/To cultivate good/and to cleanse one’s mind -/this is the teaching of the Buddhas”. That verse is so significant because it defines the basic ‘teaching of the Buddhas’ (i.e., Buddha Sasana; this is how Walpole Rahula Thera defines Buddha Sasana in his celebrated introduction to Buddhism ‘What the Buddha Taught’ first published in1959).

Twenty-five year old Anudi Gunasekera is an alumna of the University of Kelaniya, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in International Studies. She is planning to do a Master’s in the same field. Her ambition is to join the foreign service in Sri Lanka. Gen Z’er Anudi is already actively engaged in social service. The Saheli Foundation is her own initiative launched to address period poverty (i.e., lack of access to proper sanitation facilities, hygiene and health education, etc.) especially among women and post-puberty girls of low-income classes in rural and urban Sri Lanka.

Young Anudi is primarily inspired by her patriotic devotion to ‘my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka’. In post-independence Sri Lanka, thousands of young men and women of her age have constantly dedicated themselves, oftentimes making the supreme sacrifice, motivated by a sense of national identity, by the thought ‘This is our beloved Motherland, these are our beloved people’.

The rescue and recovery of Sri Lanka from the evil aftermath of a decade of subversive ‘Aragalaya’ mayhem is waiting to be achieved, in every sphere of national engagement, including, for example, economics, communications, culture and politics, by the enlightened Anudi Gunasekeras and their male counterparts of the Gen Z, but not by the demented old stragglers lingering in the political arena listening to the unnerving rattle of “Time’s winged chariot hurrying near”, nor by the baila blaring monks at propaganda rallies.

Politically active monks (Buddhist bhikkhus) are only a handful out of the Maha Sangha (the general body of Buddhist bhikkhus) in Sri Lanka, who numbered just over 42,000 in 2024. The vast majority of monks spend their time quietly attending to their monastic duties. Buddhism upholds social and emotional virtues such as universal compassion, empathy, tolerance and forgiveness that protect a society from the evils of tribalism, religious bigotry and death-dealing religious piety.

Not all monks who express or promote political opinions should be censured. I choose to condemn only those few monks who abuse the yellow robe as a shield in their narrow partisan politics. I cannot bring myself to disapprove of the many socially active monks, who are articulating the genuine problems that the Buddha Sasana is facing today. The two bhikkhus who are the most despised monks in the commercial media these days are Galaboda-aththe Gnanasara and Ampitiye Sumanaratana Theras. They have a problem with their mood swings. They have long been whistleblowers trying to raise awareness respectively, about spreading religious fundamentalism, especially, violent Islamic Jihadism, in the country and about the vandalising of the Buddhist archaeological heritage sites of the north and east provinces. The two middle-aged monks (Gnanasara and Sumanaratana) belong to this respectable category. Though they are relentlessly attacked in the social media or hardly given any positive coverage of the service they are doing, they do nothing more than try to persuade the rulers to take appropriate action to resolve those problems while not trespassing on the rights of people of other faiths.

These monks have to rely on lay political leaders to do the needful, without themselves taking part in sectarian politics in the manner of ordinary members of the secular society. Their generally demonised social image is due, in my opinion, to three main reasons among others: 1) spreading misinformation and disinformation about them by those who do not like what they are saying and doing, 2) their own lack of verbal restraint, and 3) their being virtually abandoned to the wolves by the temporal and spiritual authorities.

(To be continued)

By Rohana R. Wasala ✍️

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoEnvironmentalists warn Sri Lanka’s ecological safeguards are failing

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoDigambaram draws a broad brush canvas of SL’s existing political situation

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance