Features

Greedflation, employment and poverty

The Sri Lankan cabinet has approved a significant 40% increase in the minimum wage, aimed at assisting workers struggling with the high cost of living amidst an ongoing economic recovery from a severe financial crisis that began in early 2022. This crisis, triggered by a sharp decline in foreign exchange reserves, resulted in notable inflation, currency devaluation, and a default on foreign debt. The minimum wage will escalate from 12,500 rupees ($42) to 17,500 rupees, with the added objective of supporting those in poverty.

The Sri Lankan cabinet has approved a significant 40% increase in the minimum wage, aimed at assisting workers struggling with the high cost of living amidst an ongoing economic recovery from a severe financial crisis that began in early 2022. This crisis, triggered by a sharp decline in foreign exchange reserves, resulted in notable inflation, currency devaluation, and a default on foreign debt. The minimum wage will escalate from 12,500 rupees ($42) to 17,500 rupees, with the added objective of supporting those in poverty.

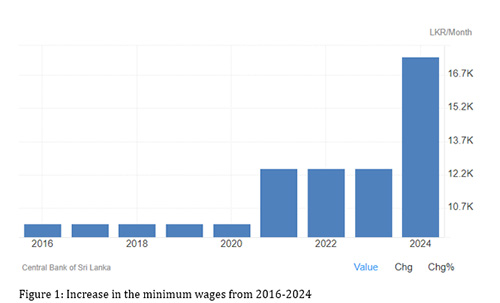

According to the National Minimum Wage of Workers Act (No. 03 of 2016), the current minimum national salary stands at Rs. 12,500/-. A subcommittee, composed of representatives from trade unions and small to medium-sized businesses, recommended raising this minimum salary to Rs. 17,500/-. The Cabinet of Ministers has sanctioned the proposal to elevate the national minimum salary by Rs. 5,000/-, from Rs. 12,500/- to Rs. 17,500/- (Figure 1). Amendments to the Act are anticipated to implement this change, with the aim of increasing the daily minimum wage from Rs. 500/- to Rs. 700/-. (See Figure 1)

Labour Department statistics show that the monthly average minimum wage in the public sector was at Rs. 34,550 at the end of 2021.

Vajira Ellepola, the Director General of the Employers’ Federation of Ceylon, noted that the increase in the minimum wage didn’t necessarily translate to a rise in the basic salary for many private sector employees. This was because most private sector basic salaries already exceeded the minimum wage threshold.

For instance, if the current minimum wage is Rs. 12,500 and an employee’s basic salary is Rs. 20,000, a rise in the minimum wage to Rs. 17,500 may not automatically lead to a proportional increase in that employee’s basic salary.

According to the Central Bank, the Non-Performing Loan (NPL) ratio in the Household sector has been steadily rising due to the constrained ability of households to repay debts. By June 2023, the NPL ratio for households had increased to 17.7%, a significant jump from the previous year’s 14.1%. The Central Bank’s Financial Stability Review for 2023 highlighted that the proportion of non-arrears loans in the Household sector has been decreasing since early 2022, while arrears loans have been increasing, indicating a continuous decline in credit quality, likely to persist if adverse economic conditions persist.

State Minister of Finance Shehan Semasinghe had mentioned that 22% of the estimated 6.2 million household units had fallen into debt due to the economic crisis. Among these units, 24.3% were urban, 20.9% rural, and 42.8% estate households. He further noted that 60.5% of household units experienced a decrease in income, while 90% saw an increase in expenses due to the economic downturn.

Greedflation

Inflation may not be the only factor increasing the price of consumer goods. There is a noticeable trend where competing manufacturers are raising their prices at varying rates, not just in comparison to each other but also in contrast to the inflation rate.

Greedflation is the concept suggesting that the pursuit of higher corporate profits is adding to the problem of high inflation. This notion has shifted from being a less common viewpoint to becoming widely discussed in Europe and the US over the past year. Similarly, there is ongoing debate about this issue in Australia.

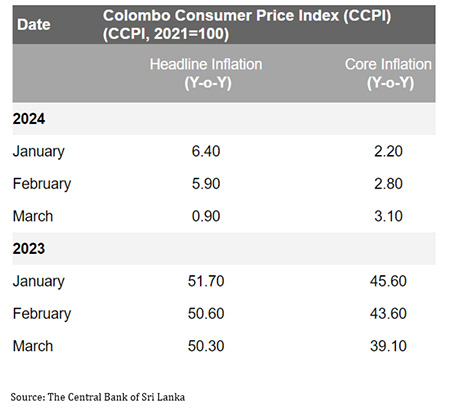

As households struggle with the increasing cost of living, certain large companies are generating record profits. Inflation is cooling in Sri Lanka. The most recent data showed the Headline inflation of March 2024 is 0.9 percent, down significantly from last March 50.3 (Table 1)

Not only are manufacturers adjusting their prices, but various entities throughout the supply chain—including shipping/transporting companies, wholesalers, and retailers—are also updating their pricing strategies accordingly.

While the yearly change in prices has decreased, the overall prices remain elevated due to previous increases. For instance, a carton of 10 large eggs still costs Rs650.00. This demonstrates that low-income households will continue to struggle with the already heightened cost of living. Hence, it is imperative that any increase in the minimum wage is supplemented with additional support measures, rather than being seen as a sole solution.

The true indicator for reducing inflation, according to some economists, is unfortunately tied to increasing unemployment. Now we’re facing the challenging reality that to curb inflation, we need to raise the unemployment rate.

Employment and minimum wages

Some people do not perceive a minimum wage as beneficial. One economic perspective suggests that minimum wages can hinder job creation by causing employers to avoid hiring more expensive labor while enticing more individuals to enter the job market.

Nobel laureate economist George Stigler expressed this viewpoint in 1976, stating that good economists typically do not support protectionist programs or minimum wage laws. However, other economists, such as David Card and Alan Krueger, have contested this notion. Their empirical studies in the 1990s found that increasing the minimum wage does not necessarily result in fewer jobs. Despite this, not all economists agree with Card and Krueger. David Neumark and William Wascher examined the evidence and argued that minimum wages do diminish employment opportunities for less skilled workers, particularly those directly impacted by the minimum wage. Consequently, there is no definitive academic consensus on minimum wages, and there is limited agreement on the conclusions drawn from the research literature.

Poverty and minimum wages

In Sri Lanka, the question arises whether minimum wage policies effectively alleviate poverty. However, research findings on this matter have been conflicting. A 2012 study conducted in New Zealand concluded that minimum wages do not necessarily lift people out of poverty. Similarly, an analysis using Irish data suggested that minimum wages might not be an effective tool for addressing poverty, describing them as “a blunt instrument.” Conversely, a 2021 study in the United States discovered significant positive employment outcomes for single mothers with young children, indicating that minimum wages could serve as a means to reduce child poverty. This issue holds particular significance in Sri Lanka due to the high prevalence of poverty among certain demographic groups.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the approval of a substantial 40% increase in the minimum wage by the Sri Lankan cabinet reflects efforts to alleviate the strain on workers facing the challenges of a recovering economy from a severe financial crisis. Triggered by a sharp decline in foreign exchange reserves, this crisis led to significant inflation, currency devaluation, and a default on foreign debt. The minimum wage rise from 12,500 rupees ($42) to 17,500 rupees aims to support those in poverty, but it may not proportionally affect all sectors due to existing salary structures.

However, the increase in minimum wage alone may not be sufficient to address the overarching issue of inflation. A broader approach, encompassing additional support measures, is necessary to mitigate the impact of the rising cost of living on low-income households. This is particularly crucial considering the steady increase in non-performing loans in the household sector, indicating ongoing financial strain. Furthermore, discussions around “greedflation” highlight the role of corporate profit expansion in exacerbating inflation, further underscoring the need for comprehensive policy responses.

In navigating these economic challenges, it is imperative to consider the interconnected nature of various factors, such as employment, poverty alleviation, and interest rates. While minimum wage policies may have differing effects on employment and poverty reduction, there is no definitive consensus, highlighting the complexity of the issue. Additionally, the management of interest rates and their impact on investors further underscores the need for careful consideration and coordination of monetary policies.

Ultimately, addressing these economic challenges requires a holistic approach that considers the diverse needs of different sectors of society and balances economic growth with social welfare objectives. It is essential for policymakers to remain vigilant and responsive to evolving economic conditions to ensure sustainable and inclusive development.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT University, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

Trump’s Venezuela gamble: Why markets yawned while the world order trembled

The world’s most powerful military swoops into Venezuela, in the dead of night, captures a sitting President, and spirits him away to face drug trafficking charges in New York. The entire operation, complete with at least 40 casualties, was announced by President Trump as ‘extraordinary’ and ‘brilliant.’ You’d think global financial markets would panic. Oil prices would spike. Stock markets would crash. Instead, something strange happened: almost nothing.

The world’s most powerful military swoops into Venezuela, in the dead of night, captures a sitting President, and spirits him away to face drug trafficking charges in New York. The entire operation, complete with at least 40 casualties, was announced by President Trump as ‘extraordinary’ and ‘brilliant.’ You’d think global financial markets would panic. Oil prices would spike. Stock markets would crash. Instead, something strange happened: almost nothing.

Oil prices barely budged, rising less than 2% before settling back. Stock markets actually rallied. The US dollar remained steady. It was as if the world’s financial markets collectively shrugged at what might be the most brazen American military intervention since the 1989 invasion of Panama.

But beneath this calm surface, something far more significant is unfolding, a fundamental reshaping of global power dynamics that could define the next several decades. The story of Trump’s Venezuela intervention isn’t really about Venezuela at all. It’s about oil, money, China, and the slow-motion collapse of the international order we’ve lived under since World War II. (Figure 1)

The Oil Paradox

Venezuela sits on the world’s largest proven oil reserves, more than Saudi Arabia, more than Russia. We’re talking about 303 billion barrels. This should be one of the wealthiest nations on Earth. Instead, it’s an economic catastrophe. Venezuela’s oil production has collapsed from 3.5 million barrels per day in the late 1990s to less than one million today, barely 1% of global supply (Figure 1). Years of corruption, mismanagement, and US sanctions have turned treasure into rubble. The infrastructure is so degraded that even if you handed the country to ExxonMobil tomorrow, it would take a decade and hundreds of billions of dollars to fix.

This explains why oil markets barely reacted. Traders looked at Venezuela’s production numbers and basically said: “What’s there to disrupt?” Meanwhile, the world is drowning in oil. The global market has a surplus of nearly four million barrels per day. American production alone hit record levels above 13.8 million barrels daily. Venezuela’s contribution simply doesn’t move the needle anymore (Figure 1).

But here’s where it gets interesting. Trump isn’t just removing a dictator. He’s explicitly taking control of Venezuela’s oil. In his own words, the country will “turn over” 30 to 50 million barrels, with proceeds controlled by him personally “to ensure it is used to benefit the people of Venezuela and the United States.” American oil companies, he promised, would “spend billions of dollars” to rebuild the infrastructure.

This isn’t subtle. One energy policy expert put it bluntly: “Trump’s focus on Venezuelan oil grants credence to those who argue that US foreign policy has always been about resource extraction.”

The Real Winners: Defence and Energy

While oil markets stayed calm, defence stocks went wild. BAE Systems jumped 4.4%, Germany’s Rheinmetall surged 6.1%. These companies see what others might miss, this isn’t a one-off. If Trump launches military operations to remove leaders he doesn’t like, there will be more.

Energy stocks told a similar story. Chevron, the only U.S. oil major currently authorised to operate in Venezuela, surged 10% in pre-market trading. ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, and oil services companies posted solid gains. Investors are betting on lucrative reconstruction contracts. Think Iraq after 2003, but potentially bigger.

The catch? History suggests they might be overly optimistic. Iraq’s oil sector was supposed to bounce right back after Saddam Hussein fell. Twenty years later, it still hasn’t reached its potential. Afghanistan received hundreds of billions in reconstruction spending, most of which disappeared. Venezuela shares the same warning signs: destroyed infrastructure, unclear property rights, volatile security, and deep social divisions.

China’s Venezuela Problem

Here’s where the story gets geopolitically explosive. China has loaned Venezuela over $60 billion, since 2007, making Venezuela China’s biggest debtor in Latin America. How was Venezuela supposed to pay this back? With oil. About 80% of Venezuelan oil exports were going to China, often at discounted rates, to service this debt.

Now Trump controls those oil flows. Venezuelan oil will now go “through legitimate and authorised channels consistent with US law.” Translation: China’s oil supply just got cut off, and good luck getting repaid on those $60 billion in loans.

This isn’t just about one country’s debt. It’s a demonstration of American power that China cannot match. Despite decades of economic investment and diplomatic support, China couldn’t prevent the United States from taking over. For other countries considering Chinese loans and partnerships, the lesson is clear: when push comes to shove, Beijing can’t protect you from Washington.

But there’s a darker flip side. Every time the United States weaponizes the dollar system, using control over oil sales, bank transactions, and trade flows as a weapon, it gives countries like China more reason to build alternatives. China has been developing its own international payment system for years. Each American strong-arm tactic makes that project look smarter to countries that fear they might be next.

The Rules Are for Little People

Perhaps the most significant aspect of this episode isn’t economic, it’s legal and political. The United States launched a military operation, captured a President, and announced it would “run” that country indefinitely. There was no United Nations authorisation. No congressional vote. No meaningful consultation with allies.

The UK’s Prime Minister emphasised “international law” while waiting for details. European leaders expressed discomfort. Latin American countries split along ideological lines, with Colombia’s President comparing Trump to Hitler. But nobody actually did anything. Russia and China condemned the action as illegal but couldn’t, or wouldn’t, help. The UN Security Council didn’t even meet, because everyone knows the US would just veto any resolution.

This is what scholars call the erosion of the “rules-based international order.” For decades after World War II, there was at least a pretense that international law mattered, that sovereignty meant something. Powerful nations bent those rules when convenient, but they tried to maintain appearances.

Trump isn’t even pretending. And that creates a problem: if the United States doesn’t follow international law, why should Russia in Ukraine? Why should China regarding Taiwan? Why should anyone?

What About the Venezuelan People?

Lost in all the analysis are the actual people of Venezuela. They’ve suffered immensely. Inflation is 682%, the highest in the world. Nearly eight million Venezuelans have fled. Those who remain often work multiple jobs just to survive, and their cupboards are still bare. The monthly minimum wage is literally 40 cents.

Many Venezuelans welcomed Maduro’s removal. He was a brutal dictator whose catastrophic policies destroyed the country. But they’re deeply uncertain about what comes next. As one Caracas resident put it: “What we don’t know is whether the change is for better or for worse. We’re in a state of uncertainty.”

Trump’s explicit focus on oil control, his decision to work with Maduro’s own Vice President, rather than democratic opposition leaders, and his promise that American companies will “spend billions”, all of this raises uncomfortable questions. Is this about helping Venezuelans, or helping American oil companies?

The Bigger Picture

Financial markets reacted calmly because the immediate economic impacts are limited. Venezuela’s oil production is already tiny. The country’s bonds were already in default. The direct market effects are manageable. But markets might miss the forest for the trees.

This intervention represents something bigger: a fundamental shift in how powerful nations behave. The post-Cold War era, with its optimistic talk of international cooperation and rules-based order, was definitively over. We’re entering a new age of imperial power politics.

In this new world, military force is back on the table. Economic leverage will be used more aggressively. Alliance relationships will become more transactional. Countries will increasingly have to choose sides between competing power blocs, because the middle ground is disappearing.

The United States might win in the short term, seizing control of Venezuela’s oil, demonstrating military reach, showing China the limits of its influence. But the long-term consequences remain uncertain. Every country watching is drawing conclusions about what it means for them. Some will decide they need to align more closely with Washington to stay safe. Others will conclude they need to build alternatives to American-dominated systems to stay independent.

History will judge whether Trump’s Venezuela gambit was brilliant strategy or reckless overreach. What we can say now is that the comfortable assumptions of the past three decades, that might not be right, that international law matters, that economic interdependence prevents conflict, no longer hold.

Financial markets may have yawned at Venezuela. But they might want to wake up. The world just changed, and the bill for that change hasn’t come due yet. When it does, it won’t be measured in oil barrels or bond prices. It will be measured in the kind of world we all have to live in, and whether it’s more stable and prosperous, or more dangerous and divided.

That’s a question worth losing sleep over.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Living among psychopaths

Bob (not his real name) who worked in a large business organisation was full of new ideas. He went out of his way to help his colleagues in difficulties. His work attracted the attention of his superiors and they gave him a free hand to do his work. After some time, Bob started harassing his female colleagues. He used to knock against them in order to kick up a row. Soon he became a nuisance to the entire staff. When the female colleagues made a complaint to the management a disciplinary inquiry was conducted. Bob put up a weak defence saying that he had no intention to cause any harm to the females on the staff. However, he was found guilty of harassing the female colleagues. Accordingly his services were terminated.

Those who conducted the disciplinary inquiry concluded that Bob was a psychopath. According to psychologists, a psychopath is a person who has a serious and permanent mental illness that makes him behave in a violent or criminal way. Psychologists believe that one per cent of the people are psychopaths who have no conscience. You may have come across such people in films and novels. The film The Silence of the Lambs portrayed a serial killer who enjoyed tormenting his innocent victims. Apart from such fictional characters, there are many psychopaths in big and small organisations and in society as well. In a reported case Dr Ahmad Suradji admitted to killing more than 40 innocent women and girls. There is something fascinating and also chilling about such people.

People without a conscience are not a new breed. Even ancient Greek philosophers spoke of ‘men without moral reason.’ Later medical professionals said people without conscience were suffering from moral insanity. However, all serial killers and rapists are not psychopaths. Sometimes a man would kill another person under grave and sudden provocation. If you see your wife sleeping with another man, you will kill one or both of them. A world-renowned psychopathy authority Dr Robert Hare says, “Psychopaths can be found everywhere in society.” He developed a method to define and diagnose psychopathy. Today it is used as the international gold standard for the assessment of psychopathy.

No conscience

According to modern research, even normal people are likely to commit murder or rape in certain circumstances. However, unlike normal people, psychopaths have no conscience when they commit serious crimes. In fact, they tend to enjoy such brutal activities. There is no general consensus whether there are degrees of psychopathy. According to Harvard University Professor Martha Stout, conscience is like a left arm, either you have one or you don’t. Anyway psychopathy may exist in degrees varying from very mild to severe. If you feel remorse after committing a crime, you are not a psychopath. Generally psychopaths are indifferent to, or even enjoy, the torment they cause to others.

In modern society it is very difficult to identify psychopaths because most of them are good workers. They also show signs of empathy and know how to win friends and influence people. The sheen may rub off at any given moment. They know how to get away with what they do. What they are really doing is sizing up their prey. Sometimes a person may become a psychopath when he does not get parental love. Those who live alone are also likely to end up as psychopaths.

Recent studies show that genetics matters in producing a psychopath. Adele Forth, a psychology professor at Carleton University in Canada, says callousness is at least partly inherited. Some psychopaths torture innocent people for the thrill of doing so. Even cruelty to animals is an act indulged in by psychopaths. You have to be aware of the fact that there are people without conscience in society. Sometimes, with patience, you might be able to change their behaviour. But on most occasions they tend to stay that way forever.

Charming people

We still do not know whether science has developed an antidote to psychopathy. Therefore remember that you might meet a psychopath at some point in your life. For now, beware of charming people who seem to be more interesting than others. Sometimes they look charismatic and sexy. Be wary of people who flatter you excessively. The more you get to know a psychopath, the more you will understand their motives. They are capable of telling you white lies about their age, education, profession or wealth. Psychopaths enjoy dramatic lying for its own sake. If your alarm bells ring, keep away from them.

According to the Psychiatric Diagnostic Manual, the behaviour of a psychopath is termed as antisocial personality disorder. Today it is also known as sociopath. No matter the name, its hallmarks are deceit and a reckless disregard for others. A psychopath’s consistent irresponsibility begets no remorse – only indifference to the emotional pain others may suffer. For a psychopath other people are always ‘things’ to be duped, used and discarded.

Psychopathy, the incapacity to feel empathy or compassion of any sort or the least twinge of conscience, is one of the more perplexing of emotional defects. The heart of the psychopath’s coldness seems to lie in their inability to make anything more than the shallowest of emotional connections.

Absence of empathy is found in husbands who beat up their wives or threaten them with violence. Such men are far more likely to be violent outside the marriage as well. They get into bar fights and battling with co-workers. The danger is that psychopaths lack concern about future punishment for what they do. As they themselves do not feel fear, they have no empathy or compassion for the fear and pain of their victims.

karunaratners@gmail.com

By R.S. Karunaratne

Features

Rebuilding the country requires consultation

A positive feature of the government that is emerging is its responsiveness to public opinion. The manner in which it has been responding to the furore over the Grade 6 English Reader, in which a weblink to a gay dating site was inserted, has been constructive. Government leaders have taken pains to explain the mishap and reassure everyone concerned that it was not meant to be there and would be removed. They have been meeting religious prelates, educationists and community leaders. In a context where public trust in institutions has been badly eroded over many years, such responsiveness matters. It signals that the government sees itself as accountable to society, including to parents, teachers, and those concerned about the values transmitted through the school system.

This incident also appears to have strengthened unity within the government. The attempt by some opposition politicians and gender misogynists to pin responsibility for this lapse on Prime Minister Dr Harini Amarasuriya, who is also the Minister of Education, has prompted other senior members of the government to come to her defence. This is contrary to speculation that the powerful JVP component of the government is unhappy with the prime minister. More importantly, it demonstrates an understanding within the government that individual ministers should not be scapegoated for systemic shortcomings. Effective governance depends on collective responsibility and solidarity within the leadership, especially during moments of public controversy.

The continuing important role of the prime minister in the government is evident in her meetings with international dignitaries and also in addressing the general public. Last week she chaired the inaugural meeting of the Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah. The composition of the task force once again reflects the responsiveness of the government to public opinion. Unlike previous mechanisms set up by governments, which were either all male or without ethnic minority representation, this one includes both, and also includes civil society representation. Decision-making bodies in which there is diversity are more likely to command public legitimacy.

Task Force

The Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka overlooks eight committees to manage different aspects of the recovery, each headed by a sector minister. These committees will focus on Needs Assessment, Restoration of Public Infrastructure, Housing, Local Economies and Livelihoods, Social Infrastructure, Finance and Funding, Data and Information Systems, and Public Communication. This structure appears comprehensive and well designed. However, experience from post-disaster reconstruction in countries such as Indonesia and Sri Lanka after the 2004 tsunami suggests that institutional design alone does not guarantee success. What matters equally is how far these committees engage with those on the ground and remain open to feedback that may complicate, slow down, or even challenge initial plans.

An option that the task force might wish to consider is to develop a linkage with civil society groups with expertise in the areas that the task force is expected to work. The CSO Collective for Emergency Relief has set up several committees that could be linked to the committees supervised by the task force. Such linkages would not weaken the government’s authority but strengthen it by grounding policy in lived realities. Recent findings emphasise the idea of “co-production”, where state and society jointly shape solutions in which sustainable outcomes often emerge when communities are treated not as passive beneficiaries but as partners in problem-solving.

Cyclone Ditwah destroyed more than physical infrastructure. It also destroyed communities. Some were swallowed by landslides and floods, while many others will need to be moved from their homes as they live in areas vulnerable to future disasters. The trauma of displacement is not merely material but social and psychological. Moving communities to new locations requires careful planning. It is not simply a matter of providing people with houses. They need to be relocated to locations and in a manner that permits communities to live together and to have livelihoods. This will require consultation with those who are displaced. Post-disaster evaluations have acknowledged that relocation schemes imposed without community consent often fail, leading to abandonment of new settlements or the emergence of new forms of marginalisation. Even today, abandoned tsunami housing is to be seen in various places that were affected by the 2004 tsunami.

Malaiyaha Tamils

The large-scale reconstruction that needs to take place in parts of the country most severely affected by Cyclone Ditwah also brings an opportunity to deal with the special problems of the Malaiyaha Tamil population. These are people of recent Indian origin who were unjustly treated at the time of Independence and denied rights of citizenship such as land ownership and the vote. This has been a festering problem and a blot on the conscience of the country. The need to resettle people living in those parts of the hill country which are vulnerable to landslides is an opportunity to do justice by the Malaiyaha Tamil community. Technocratic solutions such as high-rise apartments or English-style townhouses that have or are being contemplated may be cost-effective, but may also be culturally inappropriate and socially disruptive. The task is not simply to build houses but to rebuild communities.

The resettlement of people who have lost their homes and communities requires consultation with them. In the same manner, the education reform programme, of which the textbook controversy is only a small part, too needs to be discussed with concerned stakeholders including school teachers and university faculty. Opening up for discussion does not mean giving up one’s own position or values. Rather, it means recognising that better solutions emerge when different perspectives are heard and negotiated. Consultation takes time and can be frustrating, particularly in contexts of crisis where pressure for quick results is intense. However, solutions developed with stakeholder participation are more resilient and less costly in the long run.

Rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah, addressing historical injustices faced by the Malaiyaha Tamil community, advancing education reform, changing the electoral system to hold provincial elections without further delay and other challenges facing the government, including national reconciliation, all require dialogue across differences and patience with disagreement. Opening up for discussion is not to give up on one’s own position or values, but to listen, to learn, and to arrive at solutions that have wider acceptance. Consultation needs to be treated as an investment in sustainability and legitimacy and not as an obstacle to rapid decisionmaking. Addressing the problems together, especially engagement with affected parties and those who work with them, offers the best chance of rebuilding not only physical infrastructure but also trust between the government and people in the year ahead.

by Jehan Perera

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

News3 days ago

News3 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II