Features

Godfrey Gunatilleke’s three-volume autobiography: a monumental work

by Rajiva Wijesinha

Godfrey Gunatilleke’s autobiography, Chaos and Pattern, is an astonishingly impressive work, a veritable tour de force. It would have been remarkable from any one of any age, but that it should have been written by someone in his late nineties, from memory without recourse to a diary, makes it the more extraordinary. It is true that he began work on it thirty years ago and more, but to have persevered over the years and finally tied it together is a mark of an outstanding character.

It is an autobiography in that it tells the story of his life. The whole book, presented to all those who attended its launch last month, is divided into three parts, the first dealing with his childhood and university days, the second with his working life in government departments, the third with his reincarnation as the head of the first major think tank in the country, the Marga Institute, when he also established himself as a leading social activist.

The book is also a comprehensive account of human relationships, relationships in the family, the one in which he was born and the one that was established through his marriage, relationships between family members including in-laws, relationships with his peers who contributed to and benefited from his intellectual development, and relationships with colleagues at work including those who were involved in his social activism. These relationships are expounded in detail, analyzed in depth, and set within the framework of a committed morality that is nevertheless constantly seeking refinement, in the light of both human emotion and human weakness.

It is an illuminating account of social changes in the near century through which he has lived, examining the different political perspectives that dominated thinking in different spheres, shifting attitudes to class and caste, changing work ethics, and the decline in moral commitment on the part of politicians and bureaucrats and their hangers on. Godfrey, whose social and intellectual standing was considerable at the time I first came across him in the early eighties, through the work of the Marga Institute, came from a middle class family which he places at the lower end of that social class. His father was a notary who cut himself off to a large extent from his own family, to some extent because they had prevented his marriage to his first love.

After an arranged marriage which ended in separation, he married his original love, who had four children, while they also looked after his oldest son. Godfrey describes a difficult man who was nevertheless a supportive father, and half way through the book, in talking about his death, he engages in a retrospective account which tries to make up for any criticism he had engaged in earlier. The very positive sense of closure is typical of the quest for truth, as Trollope said was his priority in his autobiography, combined with the personal warmth that Godfrey extends to all except the very few people he finds beyond the pale.

Then in the second volume, Godfrey talks about his working life, just over 25 years in the Civil Service. He had after university worked briefly in the Income Tax Department, but that did not stretch him. The Civil Service did, and this volume recounts in great detail the way he threw himself into his work, beginning with a cadetship that took him to Jaffna and then into the Prime Minister’s office, a sure sign of someone recognized early on as a potential highflyer.

The Prime Minister then was D S Senanayake, and the early pages of the book cover the departure from government of S W R D Bandaranaike, and then Senanayake’s sudden death. The book deals with detachment with the succession of his son Dudley, though the climate of intrigue that accompanied this comes through, as does the tensions that arose because of strange political developments in the ensuing two decades: the succession as Prime Minister of Dahanayake when Bandaranaike was assassinated, the attempted coup of 1962, the hostility between Dudley Senanayake and J R Jayewardene during the UNP government of the latter part of that decade, and the insurrection of 1971.

Godfrey is particular interesting in his dissection of the shifts in the left movement, from the idealism of the Trotskyists he had admired in his university days, through the coalition with the SLFP, to the rise of a new left in the form of the JVP. He also introduces an element that has not received much attention, the different approaches of the LSSP and the CP in Mrs Bandaranaike’s 1970 government, the latter still pursuing revolutionary changes while the LSSP was more inclined to compromise.

This was particularly true with regard to foreign aid, a fascinating topic then as now, since a nation needs this for development but has to ensure that spreading the benefits of development equitably is not stymied by the manner in which aid is obtained. Interestingly, Godfrey notes the difference between Jayewardene and Esmond Wickremesinghe, and the less doctrinaire approach of Dudley Senanayake; though he also records Jayewardene’s presumably pragmatic approaches to the Bandaranaike government whereas Senanayake wanted to stay aloof. Godfrey worked essentially in just three areas during his career, in lands and then in industries and finally in planning.

A running theme through the book is the manner in which long term plans are subverted by changes of regime. He notes too the relatively comprehensive approach to government of Bandaranaike which was beyond Dahanayake, though he does pay tribute to Mrs Bandaranaike’s qualities of leadership. Godfrey is indeed positive about almost all the Ministers he worked with, though he looks at shifting perspectives that led to the increasing personal influence with regard to professional concerns. He is highly critical of only one Minister, Philip Gunawardena, whom in his gentle fashion he presents as something of a bully.

But if the main subject of this second volume of Chaos and Pattern is Godfrey’s work as a Civil Servant, it also encompasses the seminal social changes that took place during the first two decades after independence. Chief amongst these was the development of ethnic conflict and increasing violence. This sprang from the determination to make Sinhala the only official language, though Godfrey does note how the UNP repudiated the pledge of Sir John Kotelawala, then Prime Minister, to give Sinhala and Tamil parity of status.

He records how violence developed, and the way in which many Civil Servants helped to defuse tensions, though he also relates how one Civil Servant who was under pressure permitted premature shooting which led to tragic deaths. The failure of government to deal firmly with the problem is also noted, and how the Governor General Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, with solid support from the forces, brought the situation under control.

But the animosities roused were to linger, and these were exacerbated by the determination of the UNP, then under J R Jayewardene, to stymie Bandaranake’s efforts at compromise. Godfrey also notes the brain drain that began in these years, with one of his guiding lights, Dick Hensman, deciding to leave, though he then came back. He had established Community, a journal which looked at social and political issues, and attracted distinguished writers including Godfrey himself.

And after Hensman left for the second time, Godfrey began his own journal, which he called Marga, a precursor to the think tank he then set up.Side by side with the narrative of social changes is, as in the first volume, Godfrey’s account of relations within his family. This includes the story of how he and his wife Bella fell out with her family, over an incident that might have seemed trivial, had it not seemed to both of them a mark of bad faith. Their sense of what constituted obligations was acute and though in time matters settled down, the earlier camaraderie never returned.

The family unit however continued immensely satisfying and fulfilling. And though there were the occasional disagreements between husband and wife, there is an enduring spirit of devotion, which can be quite lyrical as in the description of the trip to America they went on together through the Eisenhower Fellowship Godfrey received at the beginning of 1970. He manages too to convey the sense of intellectual excitement he felt at dealing with careful analysis of new ideas, related to his particular interests at the time, not only planning, but the role of foreign capital in ensuring development.

As Dick Hensman was Godfrey’s guru for the intellectual analysis he engaged in over the years, so his guru for his professional work was Gamani Corea, who had been the main spirit behind planning for development from the fifties on. But with political changes his plans were never followed through, and to this perhaps can be traced Godfrey’s decision to leave the Civil Service soon after the change of government in 1970. But he did wait until the Five Year Plan he had been working on was completed, even though he knew by then that it would not have the impact originally envisaged.

The last volume of the autobiography looks at his life and work after he resigned from the Civil Service, in the early seventies. He did this to set up the Marga Institute, which was the first private think tank of its kind, the only one for a couple of decades, and immensely influential in that period. It was through Marga that I first met him, in the eighties, when its Legal section organized several seminars with regard to the perversion of his own constitution that J R Jayewardene was engaged in.

These however ceased when J R became more autocratic, and at the time I thought Godfrey had been pusillanimous in drawing in his horns. I recall Radhika Coomaraswamy, who left the Marga legal section to work at the International Centre for Ethnic Studies, which was set up by Neelan Tiruchelvam (who had presided over the Marga Legal Section), telling me that Godfrey had got worried when Lalith Athulathmudali asked to see the Marga articles of association.

And later she told me that, when Godfrey had been horrified at J R’s decision to have a referendum, he had been called to a meeting and emerged white and shaking, as she put it, at the claim J R had made about the threat of violence by the opposition over the Presidential election.I have dwelt on this because these shortcomings with regard to trying to check the excesses of the government in the early eighties had contributed to my early diffidence about Godfrey, and I fear that these aspects are skated over in the book.

This was the only area in the autobiography which I found disappointing, though I have also realized that in terms of the larger picture it is understandable that he did not want to break his links with government. So too he and his associates, in the Citizens’ Committee for National Harmony, set up after the excesses of the attacks on Tamils soon after the Jayewardene government came to power, were mealy-mouthed about attributing responsibility to the government for the ethnic violence of 1983. But Godfrey does acknowledge in the book that perhaps he should have been more incisive, given the evidence he had, in particular something I did not know before, that Lalith Athulathmudali had talked beforehand about the Tamils living outside the North and East having to be taught a lesson.

Godfrey tries in his analyses to be balanced, which is a quality to be respected, but I feel that it should not lead to indulgence of those beyond the pale. I noted earlier his critique of Philip Gunawardena, alone of the Ministers with whom he worked, and I wish he had applied the save incisiveness to J R Jayewardene. The nearest he comes to exposing the man’s monumental hypocrisy is when he comments, on Jayewardene’s claim that he had protected the SLFP and ‘kept the old leadership, including Mrs Bandaranaike, in control of the party’, that he ‘could not but marvel at the way in which actions, which were being condemned by his opponents as gross violations of democratic norms, were presented as interventions designed to uphold and protect democracy’.

That failure to grasp the nettle, to refrain from affirming that the driving of Mrs Bandaranaike out of politics and the referendum with the jailing of the most effective campaigner against it, were gross violations, is why I think that I was not entirely wrong in finding the Godfrey of the eighties a disappointment.

But if he seemed complaisant in the early eighties with regard to the horrendous attacks on democracy and on Tamils perpetrated by J R Jayewardene, that should not take away from the man’s great achievements, which are presented in waves as it seems in the last few chapters of the book.

For while I was concerned then about the measures taken to in effect destroy our country, Marga was not only working on legal issues, but was concerned with development, which was Godfrey’s primary concern. And his account of what was done with regard to health issues, and the care of children, are fascinating, and make it clear perhaps why he was so wary of confronting government. For the enormous respect in which he, and through him Marga, were held internationally, meant that he could engage in studies, not only in Sri Lanka but also in the region, which required cooperation with government agencies. This may not have been possible had Jayewardene turned against him and forbidden government involvement in these studies, which was what Felix Dias Bandaranaike had tried to do in the early seventies.

These accounts figure late in the book, for much of the middle is taken up with the ethnic conflict, and the efforts Godfrey made to promote consensus and reform. He worked with other agencies on this, and I was pleased at the credit he gave to the Centre for Society and Religion, headed by Fr Tissa Balasuriya, whose social commitment he found admirable, as I did too in my interactions with him.

If this is the most significant subject in this section of the autobiography, there is also much about elections, and Godfrey’s seminal role in setting up PAFFREL, the country’s principal agency for monitoring of elections. Interestingly he notes the efforts he and many of his associates made to ensure that elections were indeed held in 1988, when Jayewardene was trying to wriggle out of them as he had done in 1982. He records though his surprise that Fr Tissa too thought the time was not ripe for these though, as we all know now, those elections were what brought the country back to life, just as the elections last year, despite Ranil Wickremesinghe’s efforts to wriggle out of them, are what has restored a sense of hope when despair was mounting as it did in the late eighties.

After his full account, with detailed reflections on questions of development, and also personal relations, of the first seventy years of his life, Godfrey says comparatively little about the next quarter century. But he does refer to his break with many of his more doctrinaire associates who, through the Friday Forum, joined with local and international elements which sought to punish the Rajapaksa government and its military forces for having dealt successfully with the Tigers. Godfrey was large enough to register his realization that the Tigers were intransigent – just as earlier he had, while criticizing the intransigence of government, noted the contribution to violence of Tamil militant groups – and describes his Third Narrative which tried to set down a balanced account of what had taken place in 2009.

That balance I found admirable, and it explains why Marga had such an impact on this country and on international agencies, whereas all successors here have tended to fall in line with the agendas of their funders. It is sad then to think, in reading this thought-provoking account of a life well spent, with its record of constant searching for justification, that we shall not look upon his like again.

Features

Are we witnessing end of globalisation? What’s at stake for Sri Lanka?

Globalisation can be understood as relations between countries, and it fosters a greater relationship between countries that involve the movement of goods, services, information, technology, money, and human beings between countries. These relationships transcend economic, cultural, political, and social contexts.

Globalisation in the modern world today is a significant shift from the past. Globalisation in the modern world today is a state in which the world becomes interconnected and interdependent. This change occurs due to better technology, transport, communication, and foreign trade.

Trade routes have joined areas for centuries. The Silk Road and colonial sea trade routes are the best examples. But today, nobody can match the speed and scope of globalization.

Globalisation began to modernise after World War II. During this time, countries came to understand that they had to work together. They wanted to have economic cooperation and peace so that they would not fight any more. These significant institutions united countries for political and economic purposes and advantages. They allow free movement of products, services, and capital between countries. It encourages cooperation all over the world.

The second half of the 20th century saw fabulous technological advances. These advances sped up globalisation. The internet changed everything. It changed the way people communicate, share information, and do business. Traveling became faster and more efficient. Products and humans travel from one continent to another in record time. Companies can now do business globally. They outsource jobs, get access to global markets, and use global supply chains. This was the dawn of multinational firms and a global economy.

Flow of information is one of the characteristic features of the current age of globalisation. The internet allows news, ideas, and culture to be shared in real-time. Societies are experiencing unprecedented cultural interconnectedness. This has led to controversy over cultural sameness and dissimilation of local cultures. For example, the same is observed within countries too. In countries such as Sri Lanka the language differences between districts have become a non-issue, and the western province’s language has paved the way for others to emulate. Globalisation has allowed millions of individuals to lift themselves out of poverty, especially in Asia and Latin America. It does this by creating new employment opportunities and expanding markets. It has also increased economic inequalities, though. Wealth flows to those who possess technology and capital. Poor workers and communities are unable to compete regionally or internationally. Some countries have seen political backlash. In these countries, some people feel left behind by the benefits of globalisation.

Modern globalisation has a lot to do with environmental concerns. More production, transportation, and consumption have destroyed the planet. These are pollution, deforestation, and climate change. Global issues need global solutions. That is why international cooperation is essential in solving environmental problems. The Paris Climate Agreement is one such international effort to cooperate. There are constant debates regarding justice and responsibility between poor and rich countries.

Modern-day globalisation deeply influences our daily lives in many ways. It has opened up possibilities for economic growth, innovation, and cultural exchange. However, it also carries with it dire consequences like inequality, environmental destruction, and displacement of culture. The future of globalisation will be determined by the way we handle its impact. We have to see to it that its benefits are distributed evenly across all societies.

Tariffs are globalising-era import taxes. Governments levy them to protect domestic firms from foreign competition. But employed ruthlessly and as retaliation like today, and they can trigger trade wars. Such battles, especially between big economies such as the U.S. and China, can skew trade. They can destabilise markets and challenge the new era of globalisation. Tariff wars will slow or shift globalisation but won’t bury it.

Globalisation is not just a product of dismantling trade barriers. It is the product of enormous forces like technology, communications, and economic integration in markets across the globe. Tariffs can limit trade between countries or markets. They cannot undo the fact that most economies in the world today are interdependent. Firms, consumers, and governments depend on coordination across borders. They collaborate on energy, finance, manufacturing, and information technologies.

However, the effects of tariff wars should not be downplayed. Excessive tariffs among dominant nations compromise international supply chains. This also raises the cost for consumers and creates uncertainty for investors. The 2018 U.S.–China trade war created billions of dollars’ worth of tariffs. It also lowered the two countries’ trade. Industries such as agriculture, electronics, and automotive manufacturing lost money. These wars can harm international trade confidence. They also discourage higher economic integration.

There are some nations that are facing challenges. They are, therefore, diversifying trade blocs. Others are creating domestic industries. Some are also shifting to regional economic blocks. This may result in more fragmented globalisation. Global supply chains can become short and local. The COVID-19 pandemic and tariff tensions forced countries to re-examine the use of foreign suppliers. They began to stress self-sufficiency in vital sectors. These are medicine, technology, and food production.

Despite these trends, globalisation is not robust. The global economy can withstand crises. It does so due to innovation, new trade relations, and digitalisation. E-commerce, teleworking, and online communication link people and businesses across the globe. Sometimes these links are even stronger than before. Countries need to come together in order to combat challenges like climate change, pandemics, and cybersecurity. This is happening even as economic tensions rise.

Tariff wars can disrupt trade and create tensions.

However, they will not be likely to end globalisation, but instead, they reshape it. They might change its structure, create new partnerships, and help countries find a balance between openness and security. The globalization forces are strong and complex. They can be slowed down or reorganized, but not readily undone. The future of globalisation will depend on how countries strike their economic interests. They must also recognise their interdependence on each other in our globalised world. The world economy has a tendency to change during crises.

It does this through innovating, policy reform, building strong institutions, and changing economic behavior. But they also stimulate innovative and pragmatic responses by governments, companies, and citizens. The world economy has shown that it can heal, change, and change after crises like financial downturns, pandemics, and geo-political conflicts. One of the more notable examples of economic adjustment occurred in the 2008 global financial crisis. The crisis started when the housing market in the U.S. collapsed. The big banks collapsed, and then the effects spilled over to the world. This led to recessions, very high unemployment levels, and a drop in consumer confidence. In response, central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank acted very quickly. They cut interest rates to near zero. They also started large-scale quantitative easing. Governments spent stimulus money in their economies. They assisted in bailing out banks and introduced tax-tight financial regulations. These actions stabilised markets and ultimately restored economic growth. The crisis also led to new financial watchdog mechanisms. One example is the Financial Stability Board, which has the objective of avoiding such collapses in the future. The COVID-19 pandemic created a unique crisis.

It reached health systems and economies globally. In 2020, the world suddenly stopped. Lockdowns and supply chain disruptions followed. This led to a sharp fall in GDP in almost all countries. Sri Lanka experienced it acutely. However, the world economy has adapted at a breathtaking speed. Remote work and online shopping flourished, driven by digital technology. Firms transitioned to new formats like contactless offerings, delivery platforms, and remote platforms. Governments rolled out massive stimulus packages to businesses and employees. Central banks infused liquidity to support financial systems. International cooperation on vaccine development and distribution also helped accelerate economic recovery. By 2021 and 2022, various economies were quicker to recover than expected, though unevenly by region. Another outstanding one is the manner in which economies adapted to geostrategic struggles:

The war of 2022 between Ukraine and Russia ravaged across world markets of food and energy, with special impact on Europe and the Global South.

European nations moved swiftly to abandon Russian natural gas. European nations also looked around for other sources of energy and increased usage of renewables. While shock caused inflation as well as supply shortages to a peak first, markets began to shift ultimately. And world grain markets looked elsewhere and established new channels of commerce. Such changes show the ways that economies can change under stress, even if ancient structures are upended. Climate change is demanding long-term change in the world economy.

The climate crisis isn’t a sudden crisis, like war or pandemic. But it’s pushing nations and businesses to make big changes. Green technologies are on the rise. Electric vehicles, solar and wind power, and carbon capture are the best examples. These technologies are indicative of how economies address environment crises. Financial institutions and banks are now embracing sustainable investing guidelines. Countries are uniting in a low-carbon future under the terms of the Paris Climate Accord. Technology is leading economic resilience.

The digital economy is going stratospheric—AI, cloud computing, and e-commerce are the jetpack! These technologies enable companies to be agile and resilient. Consider the pandemic and the financial crisis, for instance. Technology businesses did not just survive; they flew like eagles. They gave us remote work tools, digital payments, and virtual conversations, allowing us to stay connected when it was most important. These innovations have irreversibly shifted the terrain of worldwide business and work. The global economy’s history is marked by crises and its capacity to adapt and transform in response. The global economy proves strong during financial crises, pandemics, conflicts, and climate issues. Resilience shines through innovation, teamwork, and strategic adjustments. Though challenges linger and vulnerabilities remain, we’re not without hope.

Learning from crises helps us fortify and adapt our systems. This adaptability signals a promising evolution for the global economy amid future uncertainties.

The current trade war, especially between the United States and China, is reshaping globalization. It may lead to a new form of it. These tensions do not terminate globalization. Instead, they push it to evolve into a more complex and regional form. The new model includes economic factors. It also includes political, technological, and security factors. This leads to a world that remains interconnected but in more cautious, selective, and fragmented ways.

Trade wars tend to begin when countries want to protect their industries.

They might want to lower trade deficits. They also respond to unfairness, including intellectual property theft or state subsidies. The ongoing trade war between China and the U.S. has seen massive tariffs, export quotas, and increasing geopolitical tensions. This is a sharp departure from the post-Cold War era, which saw more free and open trade. Now, companies and governments prepare for everything. Safety and national interests are their concerns. This change is reflective of a trend that some experts call “de-risking” or “strategic decoupling.” One of the most obvious signs of this new course is the reorganization of global supply chains.

Many global companies want to diversify away from relying on one country. They especially want to decouple from China for manufacturing and raw materials. They diversify production by investing in different regions. It is called “China plus one.” It means relocating operations to locations like Vietnam, India, and Mexico. This relocation takes global supply chains from centralized to more regionalized and redundant networks. These networks prepare for future shocks. Moreover, technology and digital infrastructure have an increasing role in this new globalization.

Trade tensions are an indication of the strategic value of semiconductors, telecommunications, and artificial intelligence. Nations are realizing that technology is a national security issue. Therefore, they have invested in their local capabilities and restricted foreign technologies’ access. The U.S., for example, has put export restrictions on high-end microchips and blocked some Chinese technology companies from accessing its market. China and other nations have increased efforts in developing independent ecosystems for technologies. This has given rise to parallel technology realms. This could result in a “bifurcated” global economy with different standards and systems. The current trade war is also strengthening the advent of regional trading blocs.

Global trade agencies like the World Trade Organization are getting weakened. This is owing to the fact that the world’s major nations are competing with one another. Hence, the nations are currently opting for regional agreements to develop economic cooperation. Discuss the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in Asia. And let’s not forget the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). Collectively, these agreements represent a new era of globalization. It’s no longer a free-for-all; rather, it’s a strategic web spun with trusted partners and regional ambitions resulting in ‘islands’ or ‘regions’ of globalization. The new model of globalization creates greater independence and security for some but presents issues.

The countries that previously prospered from the exportation of goods and involvement in the global market may face greater challenges. As protectionism rises and competition becomes greater, customers may pay more. Economic inefficiencies are a likely reason. Additionally, the disintegration of international institutions may stop countries from agreeing on important issues. Problems like global warming, pandemics, and economic downturns can become harder to resolve. The current trade war will not end globalization, but it is reshaping it. We see a new type of globalization that is fragmented, regional, and strategic in character. Countries are still interdependent, but such economic dependency is underpinned by trust, security, and competition. Globalization is changing, so we must balance these changes with the imperatives of cooperation in our globalized world.

New types of globalization include regional trade blocs, reshaping supply chains, tech decoupling, and growing geopolitical tensions.

For Sri Lanka, the changes have far-reaching consequences.

Being a small nation strategically located, Sri Lanka relies on trade, tourism, and foreign investment. Globalization is, however, more fragmented and politicized and security-oriented. This offers opportunities and challenges for Sri Lanka. To survive, the country must reform its economic policies. It must diversify relationships and maneuver the rival interests of global powers with caution.

One of the most immediate effects of the new globalization is realigning global supply chains.

Multinationals want to wean themselves from China. They want to shift production elsewhere. Sri Lanka can be a new hub for light manufacturing, logistics, and services. Being located on key shipping routes in the Indian Ocean means that it is a vital node in global ocean trade. Sri Lanka can lure more foreign investment by improving its infrastructure, bolstering digital strength, and upgrading the regulations. This would help firms to open up business. This would create employment as well as improve export-led growth. But the shift towards regionalism in global trade also poses danger.

The rest of the countries outside these alignments might be left out as major economies create closed trading blocs. Examples include the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and bilateral agreements like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. Sri Lanka is not part of most of the world’s biggest trade blocs, limiting its access to large markets and preferential trade conditions. Exclusion could make exports less competitive. It could also reduce the nation’s appeal as an international production base. To fulfill this, Sri Lanka must pursue trade agreements with regional powers like India and ASEAN nations in order to keep up with shifting trade networks. One key feature of the new era of globalization is a focus on ‘technological sovereignty’.

This includes the rise of alternative digital ecosystems, especially between China and the US. Sri Lanka must manage the tech divide wisely. Countries are closing doors to other people’s technologies and creating their own networks. Cyber security, digital infrastructure, and data governance require investments. Sri Lanka also needs to balance embracing new technology while preserving its digital sovereignty. Dependence on technology from a single country could yield dangers, as digital tools will be the main movers in the realms of governance, finance, and communication. Geopolitical competition, especially in the Indo-Pacific, also affects Sri Lanka’s economic and strategic location.

The island’s location has drawn China and India and Western nations. China’s involvement in Sri Lankan infrastructure projects, such as the Hambantota Port and the Colombo Port City, has yielded economic advantage as well as concerns regarding debt dependence and strategic control. Meanwhile, India and its allies have expressed interest in balancing Chinese power in the region. This is a sensitive balance that Sri Lanka has to exercise strategic diplomacy to reap foreign investment without being entangled in great power rivalry or compromising sovereignty. In addition, economic resilience in the face of global shocks—such as the COVID-19 pandemic, energy shocks, and food crises—has emerged as a top priority in the new era of globalization.

The recent economic slump in Sri Lanka, marked by a sovereign default, foreign exchange crises, and inflation, underscored the country’s vulnerability to global shocks. These events underscore the need for greater economic diversification, sound fiscal management, and long-term development. Sri Lanka must build stronger domestic industries, shift to clean energies, and transform regional supply systems that are less vulnerable to shocks from the outside. Generally speaking, therefore, the new patterns of globalization present Sri Lanka with a risk-laden world of possibility too.

While transforming global patterns of trade and investments creates new doors to economic growth, it steers the country towards more aggressive competition, geopolitical tensions, and internal vulnerabilities. To thrive in this fast-evolving world, Sri Lanka must adopt an assertive strategy of regional integration, technological resilience, strategic diplomacy, and inclusive economic reform. On the way, it can transform foreign uncertainty into a platform for sustainable and sovereign development.

by Professor Amarasiri de Silva

Features

Fever in children

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey),

DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK),

FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Fever is a common symptom of a variety of diseases in children. At the outset, it is very important to clearly understand that it is only a symptom and not a disease in its own right. When the body temperature is elevated above the normal level of around 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit (F) or 37 degrees Celsius (C), the condition is referred to as fever. It is a significant accompanying symptom of a plethora of childhood diseases. All children would get a fever at some time or another in their lives, and in the vast majority of cases, this is due to rather mild illnesses, and they are completely back to normal within a few days. Some may have a rather low-grade fever, while others may have quite a high fever. However, in certain situations, fever may be an important indication of an underlying serious problem. The significance depends entirely on the circumstances under which this occurrence is seen.

Irrespective of the actual underlying reason for the fever, the basic mechanism of causation of fever is the temporary resetting of the temperature-regulating thermostat of the brain to a higher level. The consequences are that the heat generated within the body is not effectively dissipated. It is merely a body response to a harmful agent and is a very important defence mechanism. Turning up the core temperature is the body’s way of fighting the germs that cause infections and making the body a less comfortable place for them. However, less commonly, it is also a manifestation of other inflammatory disorders in children. The significance of fever in such situations is a little bit different to that which is seen as a response to an infection.

The part of the human brain that controls body temperature is not fully developed in young children. This means that a child’s temperature may rise and fall very quickly and the child is also more sensitive to the temperature of his or her surroundings. Although parents often worry and get terribly scared with the child developing fever, it does not cause any harm by itself. It is a good thing in the sense that it is often the body’s way of fighting off infection.

It is quite important to note that the actual level of the temperature is not always a good guide to how ill the child is. A simple cold or other viral infection can sometimes cause a high fever in the region of 102 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit or 39 to 40 degrees Celsius. However, this does not always indicate a serious problem. It is also true to say that some more sinister infections could sometimes cause a much lower rise in the body temperature. Because fevers may rise and fall, a child with a fever might experience chills and shivering as the body tries to generate additional heat as the body temperature begins to rise. This may be followed by sweating as the body releases extra heat when the temperature starts to drop. Children with fever often breathe faster than usual and generally have a higher heart rate. However, fever accompanied by obvious difficulties in breathing, especially if the breathing problems persist even at times the temperature is normal is of significance and requires urgent medical evaluation of the situation. Generally, in the case of children, the way they act is far more important than the reading on the thermometer, and most of the time, the exact level of a child’s temperature is not particularly important, unless it is persistently very high.

Although many fevers need just simple remedies, under certain conditions the symptom of fever needs rather urgent medical attention. This is the case in babies younger than three months. Same is true even in a bigger child if the fever is accompanied by uncontrollable crying or pain in the neck with a severe headache. Marked coughing and or difficulty in breathing coupled with fever needs to be medically sorted out. Fever combined with pain and difficulty in passing urine, significant tummy pains or marked vomiting and diarrhoea too would need medical attention. Reddish rashes and bluish spots on the skin with fever also need to be seen by a doctor. The illness is probably not serious if a child with a history of fever is still interested in playing, is eating and drinking well, is alert and smiling, has a normal skin colour and looks well when his or her temperature comes down. However, even with rather low levels of fever, under certain conditions, medical attention should be sought. In situations such as when the child seems to be too ill to eat and drink, has persistent vomiting or diarrhoea, has signs of dehydration, has specific complaints like a sore throat or an earache or when fever is complicated by some other chronic illness, it is prudent for him or her to be seen by a qualified doctor.

One could take several steps to bring down a fever. It is very useful to remove most of the clothes and keep under a fan to facilitate heat loss from the body. If there is no fan available, one could try fanning with a newspaper. A very effective way of bringing down a temperature is to sponge the body with a towel soaked in water. The water must be at room temperature or a bit higher. One should not use ice or iced water on the body. Ice will lead to contraction of the blood vessels of the skin and the purpose would be lost as more heat will be conserved within the body. There is no evidence that ice on the head helps to bring down the fever or to prevent a convulsion. If a medicine is to be used, paracetamol is probably as good as any other drug, but the correct dosage according to the instructions on the container should be used for optimal benefit. The best way of calculating the appropriate dose is by using the body weight. It is very important to stress that aspirin and aspirin-containing medications should not be used in children, merely to bring down a fever.

A child with fever loses a considerable amount of fluid from the body, particularly due to sweating. It is beneficial to ensure that the child drinks plenty of fluids. A good index of the adequacy of fluid intake is the passing of normal amounts of urine. A reduced solid food intake would not matter that much just for a couple of days of fever, but in prolonged fevers adequate nutrition too becomes quite important. A child with a high temperature also needs rest and sleep. They do not have to be in bed all day if they feel like playing, but they must have the opportunity to lie down. Sick children are often tired and bad-tempered. They sleep a lot, and when they are awake, they want their parents around all the time. Perhaps it is quite useful to spoil them a little bit when they are ill and to read to them, play with them or just spend time with them. It is best to keep a child with a fever home and not send him or her to school or child care. Most doctors would agree that in simple fevers, it is quite satisfactory for the child to return to school or child care when the temperature has been normal for over 24 hours.

Trying to get the temperature down would make the child more comfortable. However, it is not essential to get it down to normal and to keep it there scrupulously. Parents often worry that either the fever simply refuses to abate or springs up again after a couple of hours. It must be realised that certain fevers have to run their course and will not come down to normal in a hurry, despite whatever measures that are undertaken. This is particularly true of viral fevers. Some parents are terribly worried at the slightest elevation of the temperature and go running to doctors looking for a “magic cure” for the fever. Many fevers do not need urgent medical attention and one could watch it for a few days and see how it progresses. Yet for all that, if there are some worrying signs then it is advisable to seek advice from a qualified doctor.

It is a familiar occurrence that many people believe that a high fever is quite dangerous. Fever by itself has no major long-lasting effects. If one appreciates that high fever is just a symptom and that it is only a reaction of the body to something untoward going on, then it is easy to consider it to be just like any other symptom of a disease. Some are also under the misconception that a high fever could cause a convulsion. This is not always the case, and a convulsion would occur only in those children who have the constitutional tendency to get them. Convulsions are not always related to high fever, and in those who are susceptible, even moderate and sometimes mild fever could trigger a convulsion. High fever does not lead to lasting brain damage in its own right either. Fever is sometimes an indication of a significant infection, but in those circumstances, the primary disease itself is the real problem. In situations where medical help is desirable, what is most important is the way a fever is sorted out and some kind of a diagnosis being made as to the real cause of the fever. The crucial component of the treatment of a fever caused by an underlying problem is the treatment of the root cause.

Features

Robbers and Wreckers

To quarrel with them is a loss of face

To have their friendship is a sad disgrace

Those lines by Bharavi were written after the fourth century A.D. when Sanskrit was already a purely literary language.

We have had the spectacle of a reporter in DC asking Donald Trump whether he regrets his lying all the time every day of his life. And, Trump responded “What did you say?” and one could see that such a possibility had never occurred to him: he was genuinely baffled.

The question here and now is whether such a thought has ever come to Anura Kumara Dissanayake and Harini Amarasuriya, both obedient servants of the US and India. For example, the prathigna given by Amarasuriya as she was sworn in by AKD as Prime Minister in a Cabinet of three. That their doings are in line with the desires of Ranil Wickremesinghe (and maybe the “aspirations” of their buddies) would translate also to the cover up of his bringing in Arjuna Mahendran, the son of a Chairman of the UNP, to trash the Central Bank and execute Ranil’s bond scam.

In the matters of managing our economy and respecting our age-old culture this lot have shown us glimpses of the lunatic self-applause that define Trump’s doings. As phrased by a commentator in the U K Guardian a few days ago Trump’s endeavours “weren’t about Making America Wealthy Again. This was much more primal. Sticking it to all the people who had laughed at him over the years. His bankruptcies. His hair. His orangeness. His stupidity. Sticking it to all those who had taken him to court and won. Now he was the most powerful person in the world. He had the whole world watching as he messed it up. He could do what he liked.”. It’s quite obvious that the last is how AKD, HA, Yapa and the top tier of those most culpable have read their horoscopes: they do not expect to be held accountable

“The U.S.’s new tariff policy reflects a broader shift away from globalisation and towards economic nationalism and national balance sheet economic model approach”. So wrote a self-styled Business Cycle Economist last week. That is the kind of delusion that ‘growth-friendly’ market theory such ‘economists’ are trained to shove down the throats of politicians possessed of just about the bit of wit required to enrich themselves in tandem with the IMF and those entrepreneurs it supports.

At this point we should note also that Trump’s new wave of tariffs was harshest on Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka––all, coincidentally, in addition to their strategic importance for war-mongers, Buddhist countries.

How closely those who call the shots among the power-wielders here follow Trump is seen in their response or lack of one to the earthquake that has devastated Myanmar and Thailand a week ago. The USA has been salivating over the riches of Myanmar for a long time, confident that Aung Suu Kyi would deliver them on a platter. That no doubt was the object of the aragalaya here and seems within reach for India now.

For months now, from 2022 at least, there have been markers that showed who was running the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (so calling themselves) and what their agenda was with respect to our country and her people. An early eruption that showed their hand was that aragalaya‘. It was designed to ensure a regime change that would place, let us for convenience say, Adani in charge. It involved, as a first step, getting Gotabhaya out of the presidency. That it was so was also shown two years ago in the London Review of Books by Pankaj Misra in an essay titled “The BIG CON” on Modi’s India. In which Gotabhaya and Adani are mentioned and the above object specified.

Misra’s latest work has been on “The World After Gaza” – a reference not without its applications not only to Modi’s support for Adani in Haifa, but to the ridiculous and altogether culpable gestures of friendship towards the US-Israeli led coalition of criminals shown by Ranil Wickremasinghe and associated Colombians who succeeded him. Haifa is the largest port in that segment of occupied Palestine and the Trump group also has had a stake in it.

I shall pause here with the concluding lines of Bharavi’s quatrain.

One of sterling judgment realizes

What fools are worth and foolish ones despises.

by Gamini Seneviratne

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoColombo Coffee wins coveted management awards

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDaraz Sri Lanka ushers in the New Year with 4.4 Avurudu Wasi Pro Max – Sri Lanka’s biggest online Avurudu sale

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoStarlink in the Global South

-

Business7 days ago

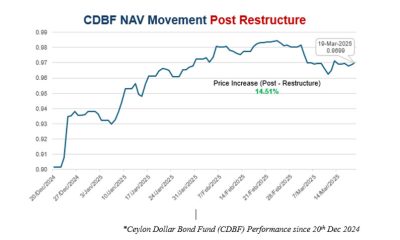

Business7 days agoNew SL Sovereign Bonds win foreign investor confidence

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part III

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoModi’s Sri Lanka Sojourn

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoInequality is killing the Middle Class

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part I