Features

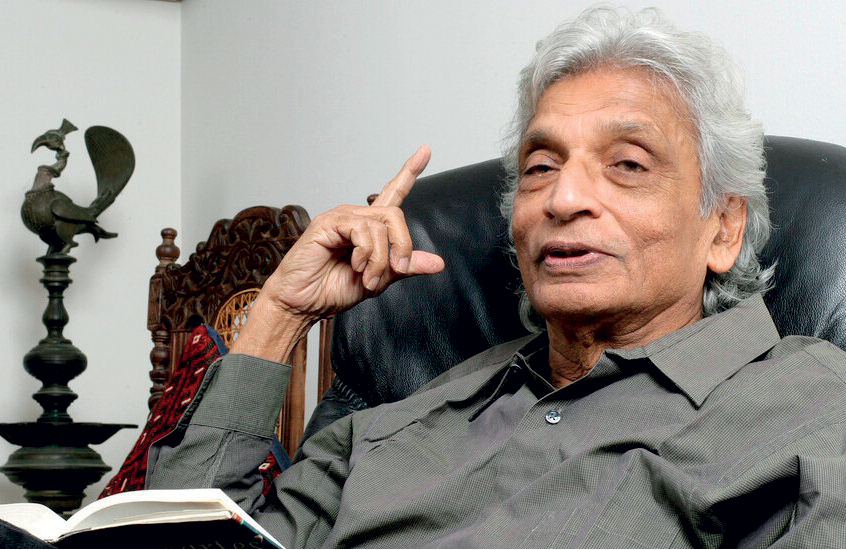

Gananath Obeysekere’s ‘foolishness’ and the liberation from complicities

PART 1

One of the most fascinating lectures I’ve attended is the one delivered by Gananath Obeysekere at the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka on the Vädda, more than twenty years ago. It was based on research conducted in the Bibile region with H G Dayasisira in 1999-2001. Further research had been conducted between 2007 and 2009. The project apparently was one that ‘envisaged a critique and a follow-up of ‘The Veddas,’ the classic study by C G and Brenda Z Seligmann who believed they were dealing with one of the world’s most ‘primitive’ hunting and gathering groups. The outcome of the exercise was Gananath’s 2002 book ‘The Creation of the Hunter.’

The title has the following rider: ‘The Vädda presence in the Kandyan Kingdom: A re-examination.’ The keyword is ‘re-examination.’ Obeysekere revisits the wild man thesis offered by the Seligmanns and of course his own research a decade or so before. Indeed, Obeysekere’s academic life is essentially filled with re-visitations of one kind or another.

Liyanage Amarakeerthi, in a speech delivered in August 2023 on the occasion of an event where Obeysekere handed over his personal library, the Obeysekere Collection, to the University of Peradeniya, details instances where Obeysekere has challenged received knowledge. For example, he cites Obeysekere’s engagement with Edmund Leach in ‘Medusa’s Hair,’ with Marshall Sahlins in ‘The apotheosis of Captain Cook,’ with Western rationalism in ‘Awakened Ones: Phenomenology of Visionary Experience,’ and with what Amarakeerthi sees as ‘nationalist forces that brought the county down, [by] promoting extreme chauvinism and xenophobia,’ in ‘The many faces of the Kandyan Kingdom.’ One could add to this, ‘Buddhism Transformed: Religious Change in Sri Lanka,’ which Gananath co-authored by Richard Gombrich.

These revisitations certainly generated debate and fuelled much academic forays into the fields that Obeysekere explored. Revisitation of re-examination as Obeysekere puts it is obviously a key element in the social sciences in general and in history and anthropology (and related fields) in particular. Theses are generated by the examination of and reflection on information available or unearthed. Further discoveries compel scholars to revisit theories and make necessary adjustments or even abandon them altogether.

Obeysekere acknowledges the import of reconsideration, even of his own work. In an interview with Jayadeva Uyangoda aired on YouTube in 2016 titled ‘The foolishness of Gananath Obeysekere,’ when he was already close to 90 years of age, the anthropologist admits that he ‘made errors of fact and errors of interpretation.’ He quotes Friedrich Nietzsche: ‘One must be very humane to say I don’t know that.’ He asks (and answers), ‘How many of us are capable of pleading ignorance? I am. That’s why I praise foolishness.’

He eloquently summarizes the dilemmas of the social sciences. ‘Human sciences are vulnerable. The human sciences have an adolescent character. That is, he (Nietzsche) calls it the fate of our times. With these kinds of work there’s a kind of incompleteness. We can’t produce a finished product. All of anthropology is like that.’

He adds, ‘ours, as against the kind of natural sciences, are argumentative disciplines. And as argumentative disciplines they are also vulnerable. You can’t produce some kind of inter-subjective consensus that everyone will agree to. We may claim to be objective. You have to balance yourself, produce your empirical investigations which require evidential support. We are creatures who are basically argumentative. There is truth-value, otherwise we won’t be writing, but truth, as I always say, should be in inverted commas.’

This is why Obeysekere probably revisited his work and that of others. He was relentless. Truth, as received, comes in inverted commas. Unfortunately, there are certain truths which those who champion Obeysekere choose to write without the qualifier, as Obeysekere himself has done on occasion. That’s a disservice to Obeysekere, obviously, and one likes to think that Obeysekere, if such errors of commission and omission, i.e. of both fact and interpretation, were pointed out, would have engaged with such theses in the spirit of the foolishness that he praises.

It is important to examine the truths (without inverted commas) that seem to have pervaded Obeysekere’s work, especially on two important scholarly interventions, his explorations of the Vädda and related and preceding narratives, and his essay on Dutugemunu’s conscience, the latter ‘truth’ being reiterated by like-minded scholars in the social sciences and humanities, again without inverted commas.

‘Duṭṭhagâmani and the Buddhist Conscience’ was an essay derived from a lecture by the same title delivered by Obeysekere at the 13th conference on South Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA in November 1984. It was included in a collection titled ‘Religion and political conflict in South Asia,’ edited by Douglas Allen in 2004. The text was translated into Sinhala in the early 1990s by Sunil Gunasekera and published by the Social Scientists’ Association in the magazine ‘Yathra’ and later in the website by the ‘Kathika Sanvada Mandapaya.’

The truth (or otherwise) presented by Obeysekere in his essay was comprehensively reviewed by Ishankha Malsiri in ‘Dutugemunuge Harda Saakshiyata Pilithurak (A response to Dutugemunu’s Conscience),’ in 2016. Malsiri examines Obeysekere’s sources and in some instances points out errors of omission and commission, especially with regard to the ‘true’ location of Elara’s grave and the purported mischief indulged in by archaeologists, as representative of the state, implying of course some ideological bent and outcome preferences subscribed to by some at the time. He points out the contradictions, inconsistencies, ambiguities and witting or unwitting obfuscations in the text and concludes that the thesis is untenable.

Interestingly, Malsiri includes in his book, as addendum, the Sinhala version of Obeysekere’s talk/essay. Obeysekere’s angst is evident therein, as it is in his work on the Väddas, the contemporary expression of Buddhist practices and the intrigue associated with the Kandyan Kingdom. He correctly and importantly points to the danger of a single narrative and the tendency of such positions to concretise or, as he would put it, remove the inverted commas of ‘truth,’ and thereby argues for a more nuanced, tolerant and humane reading of history, in particular the caricatured versions as touted by the politically inclined, including certain scholars. Nevertheless, Obeysekere cannot seem to divest himself of his own reading of the antecedents of the crises or turbulences he was born into and lived through, especially after political independence was obtained from the British. It is a malady that seems to have infected his ideological fellow-travellers who, interestingly and in contradistinction to Obeysekere’s conscious embracing of foolishness, appear not to have the wider-gaze, if you will, of the anthropologist.

Whereas Obeysekere uses Dutugemunu’s ‘avowed’ discovery of a conscience towards the end of his, Dutugemunu’s, life in order to champion multiple and even contradictory narratives, his, Obeysekere’s, acolytes remain uncritical and ‘un-foolish’ even as they rant and rave against the alleged foolishness (not in the vein that Obeysekere uses the word of course) and even mischievous ways of those who are ideologically and politically opposed to their point of view.

Amarakeerthi, for example, while claiming, probably correctly in the main, that ‘Obeysekere was turned into a national villain in [the] extremely one-dimensional nationalist/racist press,’ and that Peradeniya university produce[d] scholars who argue that Dutugemunu, by extension Sinhala people, has no sense of guilt in their conscience,’ inexplicably jumps to the following conclusion: ‘No wonder that Sri Lanka has descended into the political, ethical, cultural abyss that it is in right now.’ He opines that ‘nationalist forces’ are promoting extreme chauvinism and xenophobia, a claim that can be defended in the case of certain nationalists but not all, but his assertion that it was nationalist forces ‘that brought the country down,’ is a frivolous, mischievous, unsubstantiated and reductionist claim. Obeysekera, for all his problemetisation of identity and pluralisation postulates, does descend to the kind of monolithisation, if you will, that such claims are predicated upon. We shall return to this presently.

Malsiri proposes that Obeysekere’s objective is to denigrate contemporary Buddhist society which, admittedly, Obeysekere often treats as a monolithic entity and frivolously implies is lacking in conscience. In this, as Malsiri points out, Obeysekere is not alone. Malsiri offers a list of academics whose work is premised similarly, i.e. the Sinhala-Buddhist is the villain of the piece not only for what is erroneously or at least incompletely described as ‘the ethnic conflict’ but all major ills that has plagued the island nation for many, many decades. They include Bardwell Smith, Sachi Ponnambalam, S J Thambiah, George Bond, Jeyaratnam Wilson, Stephen Kemperer, David Littleton and H L Seneviratne.

The ontological error is most evident in Obeysekere’s work on the Väddas. The text reads as an illuminating narrative on who was who and when of peoples in the island, pertaining to the Väddas and the Sinhalas and the overarching factor of Buddhism, Buddhist (society) and related othernesses. He not only rubbishes the notion of the Vädda as a wild character as described by the Seligmanns and others, but problematises identity and relatedness of both the Väddas and the Sinhalas in the areas he focused his research on. Obeysekere forces the reader to consider the likelihood that the Vädda-trace, if you will, even if ever they lived in isolation, was not and, as importantly, is not absent in ‘Sinhala’ DNA. Nevertheless, and surprisingly, he is flippant when it comes to the origin of the Sinhalas and, inter alia, the Tamils, in this island.

Part 2 Continued Next Week

by Malinda Seneviratne ✍️

Features

The call for review of reforms in education: discussion continues …

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The statement by 94 university teachers deplores the high handed manner in which the reforms were hastily formulated, and without public consultation. It underlines the problems with the substance of the reforms, particularly in the areas of the structure of education, and the content of the text books. The problem lies at the very outset of the reforms, with the conceptual framework. While the stated conceptualisation sounds fancifully democratic, inclusive, grounded and, simultaneously, sensitive, the detail of the reforms-structure itself shows up a scandalous disconnect between the concept and the structural features of the reforms. This disconnect is most glaring in the way the secondary school programme, in the main, the junior and senior secondary school Phase I, is structured; secondly, the disconnect is also apparent in the pedagogic areas, particularly in the content of the text books. The key players of the “Reforms” have weaponised certain seemingly progressive catch phrases like learner- or student-centred education, digital learning systems, and ideas like moving away from exams and text-heavy education, in popularising it in a bid to win the consent of the public. Launching the reforms at a school recently, Dr. Amarasuriya says, and I cite the state-owned broadside Daily News here, “The reforms focus on a student-centered, practical learning approach to replace the current heavily exam-oriented system, beginning with Grade One in 2026 (https://www.facebook.com/reel/1866339250940490). In an address to the public on September 29, 2025, Dr. Amarasuriya sings the praises of digital transformation and the use of AI-platforms in facilitating education (https://www.facebook.com/share/v/14UvTrkbkwW/), and more recently in a slightly modified tone (https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/PM-pledges-safe-tech-driven-digital-education-for-Sri-Lankan-children/108-331699).

The idea of learner- or student-centric education has been there for long. It comes from the thinking of Paulo Freire, Ivan Illyich and many other educational reformers, globally. Freire, in particular, talks of learner-centred education (he does not use the term), as transformative, transformative of the learner’s and teacher’s thinking: an active and situated learning process that transforms the relations inhering in the situation itself. Lev Vygotsky, the well-known linguist and educator, is a fore runner in promoting collaborative work. But in his thought, collaborative work, which he termed the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is processual and not goal-oriented, the way teamwork is understood in our pedagogical frameworks; marks, assignments and projects. In his pedagogy, a well-trained teacher, who has substantial knowledge of the subject, is a must. Good text books are important. But I have seen Vygotsky’s idea of ZPD being appropriated to mean teamwork where students sit around and carry out a task already determined for them in quantifying terms. For Vygotsky, the classroom is a transformative, collaborative place.

But in our neo liberal times, learner-centredness has become quick fix to address the ills of a (still existing) hierarchical classroom. What it has actually achieved is reduce teachers to the status of being mere cogs in a machine designed elsewhere: imitative, non-thinking followers of some empty words and guide lines. Over the years, this learner-centred approach has served to destroy teachers’ independence and agency in designing and trying out different pedagogical methods for themselves and their classrooms, make input in the formulation of the curriculum, and create a space for critical thinking in the classroom.

Thus, when Dr. Amarasuriya says that our system should not be over reliant on text books, I have to disagree with her (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/29/education-reform-to-end-textbook-tyranny ). The issue is not with over reliance, but with the inability to produce well formulated text books. And we are now privy to what this easy dismissal of text books has led us into – the rabbit hole of badly formulated, misinformed content. I quote from the statement of the 94 university teachers to illustrate my point.

“The textbooks for the Grade 6 modules . . . . contain rampant typographical errors and include (some undeclared) AI-generated content, including images that seem distant from the student experience. Some textbooks contain incorrect or misleading information. The Global Studies textbook associates specific facial features, hair colour, and skin colour, with particular countries and regions, and refers to Indigenous peoples in offensive terms long rejected by these communities (e.g. “Pygmies”, “Eskimos”). Nigerians are portrayed as poor/agricultural and with no electricity. The Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy textbook introduces students to “world famous entrepreneurs”, mostly men, and equates success with business acumen. Such content contradicts the policy’s stated commitment to “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Is this the kind of content we want in our textbooks?”

Where structure is concerned, it is astounding to note that the number of subjects has increased from the previous number, while the duration of a single period has considerably reduced. This is markedly noticeable in the fact that only 30 hours are allocated for mathematics and first language at the junior secondary level, per term. The reduced emphasis on social sciences and humanities is another matter of grave concern. We have seen how TV channels and YouTube videos are churning out questionable and unsubstantiated material on the humanities. In my experience, when humanities and social sciences are not properly taught, and not taught by trained teachers, students, who will have no other recourse for related knowledge, will rely on material from controversial and substandard outlets. These will be their only source. So, instruction in history will be increasingly turned over to questionable YouTube channels and other internet sites. Popular media have an enormous influence on the public and shapes thinking, but a well formulated policy in humanities and social science teaching could counter that with researched material and critical thought. Another deplorable feature of the reforms lies in provisions encouraging students to move toward a career path too early in their student life.

The National Institute of Education has received quite a lot of flak in the fall out of the uproar over the controversial Grade 6 module. This is highlighted in a statement, different from the one already mentioned, released by influential members of the academic and activist public, which delivered a sharp critique of the NIE, even while welcoming the reforms (https://ceylontoday.lk/2026/01/16/academics-urge-govt-safeguard-integrity-of-education-reforms). The government itself suspended key players of the NIE in the reform process, following the mishap. The critique of NIE has been more or less uniform in our own discussions with interested members of the university community. It is interesting to note that both statements mentioned here have called for a review of the NIE and the setting up of a mechanism that will guide it in its activities at least in the interim period. The NIE is an educational arm of the state, and it is, ultimately, the responsibility of the government to oversee its function. It has to be equipped with qualified staff, provided with the capacity to initiate consultative mechanisms and involve panels of educators from various different fields and disciplines in policy and curriculum making.

In conclusion, I call upon the government to have courage and patience and to rethink some of the fundamental features of the reform. I reiterate the call for postponing the implementation of the reforms and, in the words of the statement of the 94 university teachers, “holistically review the new curriculum, including at primary level.”

(Sivamohan Sumathy was formerly attached to the University of Peradeniya)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Sivamohan Sumathy

Features

Constitutional Council and the President’s Mandate

The Constitutional Council stands out as one of Sri Lanka’s most important governance mechanisms particularly at a time when even long‑established democracies are struggling with the dangers of executive overreach. Sri Lanka’s attempt to balance democratic mandate with independent oversight places it within a small but important group of constitutional arrangements that seek to protect the integrity of key state institutions without paralysing elected governments. Democratic power must be exercised, but it must also be restrained by institutions that command broad confidence. In each case, performance has been uneven, but the underlying principle is shared.

Comparable mechanisms exist in a number of democracies. In the United Kingdom, independent appointments commissions for the judiciary and civil service operate alongside ministerial authority, constraining but not eliminating political discretion. In Canada, parliamentary committees scrutinise appointments to oversight institutions such as the Auditor General, whose independence is regarded as essential to democratic accountability. In India, the collegium system for judicial appointments, in which senior judges of the Supreme Court play the decisive role in recommending appointments, emerged from a similar concern to insulate the judiciary from excessive political influence.

The Constitutional Council in Sri Lanka was developed to ensure that the highest level appointments to the most important institutions of the state would be the best possible under the circumstances. The objective was not to deny the executive its authority, but to ensure that those appointed would be independent, suitably qualified and not politically partisan. The Council is entrusted with oversight of appointments in seven critical areas of governance. These include the judiciary, through appointments to the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, the independent commissions overseeing elections, public service, police, human rights, bribery and corruption, and the office of the Auditor General.

JVP Advocacy

The most outstanding feature of the Constitutional Council is its composition. Its ten members are drawn from the ranks of the government, the main opposition party, smaller parties and civil society. This plural composition was designed to reflect the diversity of political opinion in Parliament while also bringing in voices that are not directly tied to electoral competition. It reflects a belief that legitimacy in sensitive appointments comes not only from legal authority but also from inclusion and balance.

The idea of the Constitutional Council was strongly promoted around the year 2000, during a period of intense debate about the concentration of power in the executive presidency. Civil society organisations, professional bodies and sections of the legal community championed the position that unchecked executive authority had led to abuse of power and declining public trust. The JVP, which is today the core part of the NPP government, was among the political advocates in making the argument and joined the government of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga on this platform.

The first version of the Constitutional Council came into being in 2001 with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution during the presidency of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. The Constitutional Council functioned with varying degrees of effectiveness. There were moments of cooperation and also moments of tension. On several occasions President Kumaratunga disagreed with the views of the Constitutional Council, leading to deadlock and delays in appointments. These experiences revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of the model.

Since its inception in 2001, the Constitutional Council has had its ups and downs. Successive constitutional amendments have alternately weakened and strengthened it. The 18th Amendment significantly reduced its authority, restoring much of the appointment power to the executive. The 19th Amendment reversed this trend and re-established the Council with enhanced powers. The 20th Amendment again curtailed its role, while the 21st Amendment restored a measure of balance. At present, the Constitutional Council operates under the framework of the 21st Amendment, which reflects a renewed commitment to shared decision making in key appointments.

Undermining Confidence

The particular issue that has now come to the fore concerns the appointment of the Auditor General. This is a constitutionally protected position, reflecting the central role played by the Auditor General’s Department in monitoring public spending and safeguarding public resources. Without a credible and fearless audit institution, parliamentary oversight can become superficial and corruption flourishes unchecked. The role of the Auditor General’s Department is especially important in the present circumstances, when rooting out corruption is a stated priority of the government and a central element of the mandate it received from the electorate at the presidential and parliamentary elections held in 2024.

So far, the government has taken hitherto unprecedented actions to investigate past corruption involving former government leaders. These actions have caused considerable discomfort among politicians now in the opposition and out of power. However, a serious lacuna in the government’s anti-corruption arsenal is that the post of Auditor General has been vacant for over six months. No agreement has been reached between the government and the Constitutional Council on the nominations made by the President. On each of the four previous occasions, the nominees of the President have failed to obtain its concurrence.

The President has once again nominated a senior officer of the Auditor General’s Department whose appointment was earlier declined by the Constitutional Council. The key difference on this occasion is that the composition of the Constitutional Council has changed. The three representatives from civil society are new appointees and may take a different view from their predecessors. The person appointed needs to be someone who is not compromised by long years of association with entrenched interests in the public service and politics. The task ahead for the new Auditor General is formidable. What is required is professional competence combined with moral courage and institutional independence.

New Opportunity

By submitting the same nominee to the Constitutional Council, the President is signaling a clear preference and calling it to reconsider its earlier decision in the light of changed circumstances. If the President’s nominee possesses the required professional qualifications, relevant experience, and no substantiated allegations against her, the presumption should lean toward approving the appointment. The Constitutional Council is intended to moderate the President’s authority and not nullify it.

A consensual, collegial decision would be the best outcome. Confrontational postures may yield temporary political advantage, but they harm public institutions and erode trust. The President and the government carry the democratic mandate of the people; this mandate brings both authority and responsibility. The Constitutional Council plays a vital oversight role, but it does not possess an independent democratic mandate of its own and its legitimacy lies in balanced, principled decision making.

Sri Lanka’s experience, like that of many democracies, shows that institutions function best when guided by restraint, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to the public good. The erosion of these values elsewhere in the world demonstrates their importance. At this critical moment, reaching a consensus that respects both the President’s mandate and the Constitutional Council’s oversight role would send a powerful message that constitutional governance in Sri Lanka can work as intended.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Gypsies … flying high

The scene has certainly changed for the Gypsies and today one could consider them as awesome crowd-pullers, with plenty of foreign tours, making up their itinerary.

The scene has certainly changed for the Gypsies and today one could consider them as awesome crowd-pullers, with plenty of foreign tours, making up their itinerary.

With the demise of Sunil Perera, music lovers believed that the Gypsies would find the going tough in the music scene as he was their star, and, in fact, Sri Lanka’s number one entertainer/singer,

Even his brother Piyal Perera, who is now in charge of the Gypsies, admitted that after Sunil’s death he was in two minds about continuing with the band.

However, the scene started improving for the Gypsies, and then stepped in Shenal Nishshanka, in December 2022, and that was the turning point,

With Shenal in their lineup, Piyal then decided to continue with the Gypsies, but, he added, “I believe I should check out our progress in the scene…one year at a time.”

The original Gypsies: The five brothers Lal, Nimal, Sunil, Nihal and Piyal

They had success the following year, 2023, and then decided that they continue in 2024, as well, and more success followed.

The year 2025 opened up with plenty of action for the band, including several foreign assignments, and 2026 has already started on an awesome note, with a tour of Australia and New Zealand, which will keep the Gypsies in that part of the world, from February to March.

Shenal has already turned out to be a great crowd puller, and music lovers in Australia and New Zealand can look forward to some top class entertainment from both Shenal and Piyal.

Piyal, who was not much in the spotlight when Sunil was in the scene, is now very much upfront, supporting Shenal, and they do an awesome job on stage … keeping the audience entertained.

Shenal is, in fact, a rocker, who plays the guitar, and is extremely creative on stage with his baila.

‘Api Denna’ Piyal and Shenal

Piyal and Shenal also move into action as a duo ‘Api Denna’ and have even done their duo scene abroad.

Piyal mentioned that the Gypsies will feature a female vocalist during their tour of New Zealand.

“With Monique Wille’s departure from the band, we now operate without a female vocalist, but if a female vocalist is required for certain events, we get a solo female singer involved, as a guest artiste. She does her own thing and we back her, and New Zealand requested for a female vocalist and Dilmi will be doing the needful for us,” said Piyal.

According to Piyal, he originally had plans to end the Gypsies in the year 2027 but with the demand for the Gypsies at a very high level now those plans may not work out, he says.

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition

-

Editorial3 days ago

Editorial3 days agoGovt. provoking TUs