Features

Former Commercial Bank HR Manager publishes book on Islamaphobia

By Ifham Nizam

Many write simply to showcase their talent. However, there are others who approach writing as a spiritual practice and a means of self-discovery. For them, writing allows them to perceive realities beyond the five senses. It is also a medium through which history and cultural essence are preserved, preventing their disappearance. Regardless of individual recognition, these writers see their craft as a mission.

To Lukman Harees, a UK-based bilingual author, poet, and award-winning writer, writing and poetry are a lifelong passion. With a background in law and business management, he left his job as Head of Human Resources Development at the Commercial Bank in 2004 to settle in the UK with his family.

He has contributed regularly to Colombo Telegraph and numerous Sri Lankan and international publications. He is frequently invited for panel discussions on socio-political issues related to Sri Lanka, including engagements with BBC Berkshire and events organized by the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

He is actively involved in diaspora projects aimed at fostering mutual understanding and social harmony in Sri Lanka and was a panel speaker at a UN event in Geneva in 2018 on communal violence in Sri Lanka and continues to advocate social justice and human rights.

The author of seven books in English and Sinhala focusing on sociological and human rights issues, his upcoming book, ‘Muslim on the Dock‘, explores the impact of Islamophobia on the collective Muslim psyche.

In an interview with Sunday Island, he emphasized how writing enables him to spotlight human rights, abuses and empower marginalized voices, describing this work as spiritually rewarding and beneficial to society at large.

Reflecting on his upbringing in Galle Fort and the influence of his family, particularly his father, a respected educationist and poet known as Harees Master, Lukman credits his early years for his passion for writing and poetry.

In a career spanning over 25 years in banking, he transformed the Staff Development Centre of the Commercial Bank into a profitable entity and forged partnerships with institutions such as the Asian Institute of Technology and the Indian Institute of Bankers. He was also actively involved in trade union activities in his early career.

In the UK, he has served as a Trustee and Director of ACRE (Alliance for Cohesion and Racial Equality), supporting victims of racism, and currently holds a board seat in a UK-based human rights organization.

Lukman’s books delve into sociological themes and challenge social injustices worldwide. His favorite, ‘Mirage of Dignity in the Highways of Human Progress’, published in 2012, remains a seminal work on human rights and dignity.

His latest book, ‘Muslims in the Dock’, explores the multifaceted challenges of Islamophobia and its impact on post 9/11 Muslims advocates human dignity, equality, and fraternity.

Addressing Islamophobia, Lukman argues that despite global treaties and legislation, discrimination persists, perpetuated by religious fundamentalists, academics, and commercial interests. He critiques the post 9/11 era for fostering a defeatist mentality among Muslims and calls for a renewed commitment to justice and dignity.

“I was born in 1959 and hail from Galle Fort, as the eldest child of M S M Harees, the renown educationist, writer and poet and Husna Harees. My father’s maternal grandfather, Quadir Samsuddeen, was also a renown Arabic Tamil (Arawi language) poet cum scholar who composed the well known Prophetic Ode named Mubarak Maaali which is still being recited annually during the month of Rabiul Awwal, in which the birth of Prophet of Islam (OWBP) is commemorated.

“My maternal uncle was Moulavi M A C A Lafir, who was in the translation team of the Quran into Sinhala, the first project of its kind launched by MICH, Colombo. It was this family background which primarily enthused me to engage in writing and poetry from my growing years.

“I had my initial education at St Aloysius College, Galle and pursued my Advanced Level at Royal College, Colombo. I had the privilege of completing the GCE (Ordinary Level ) in both English and Sinhala mediums with distinction,” he said.

He was involved in social service right from his late teens later becoming the general secretary of one of the leading Muslim organizations in the Southern province, the Galle Muslim Cultural Association (GMCA) . He represented the GMCA in the six-member delegation which attended the Anniversary Celebration of the Iranian Revolution in Teheran in 1982.

“In view of my bilingual ability, I engaged in regular translation assignments from English to Sinhala and vice versa. Writing poetry and articles to local magazines from my school days have been in my blood.”

A banker for over 25 years when he left with his family for the UK in 2004, he was a Fellow of Institute of Training and Development, becoming the Head of Human Resources Development (HRD) at Commercial Bank of Ceylon Limited. In his early years in the bank, he was actively involved in trade union activities, becoming Branch Secretary of Ceylon Bank Employees Union (CBEU) at the Commercial Bank in 1984. He has extensively travelled aboard including to Japan, South Korea, UAE, India, Thailand and Singapore for management training.

He says Muslims in the Dock through “a bystander’s perspective addresses how multi-pronged Islamophobia-related challenges, coupled with a defeatist mentality, are sadly pinning down post 09/11 Muslims.” He takes a wide- ranging approach to deal with almost every important aspect of Islamophobia.

Features

The Wrath of a Nation

by Anura Gunasekera

The wrath of a nation can be a fearful thing. In 2022 we saw its evolution and culmination in our own “Aragalaya“, which sent the then president, a so called “battle hardened” war veteran and “warrior-statesman”, first in to exile and then to precipitate retirement.

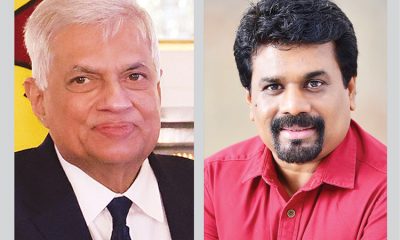

We saw it again, just a couple of weeks ago, in the election of Sri Lanka’s ninth executive president, a villager from deeply rural Tambuttegama, the son of a surveyor’s assistant. That he was the first student from Tambuttegama Central College to gain university entrance, is another factor which attests to the absence of privilege and personal resources. His election is also an extension of the “Aragalaya”, and a logical evolution of that movement, but without the drama and histrionics and, instead, that energy, that anger, legitimately channeled in to a quiet civic purpose.

Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) is an unlikely incumbent in the presidential palace, not only because of his very modest background, but also because of the baggage and history of violence, against the very people and the institutions he is now going to govern, perpetrated by the political party which sponsored him. The late Ranasinghe Premadasa, too, came from the urban equivalent of social irrelevance but, by the time he became president of the country, he was already a towering force in national politics.

Most of the 5.7 million people who voted AKD in to power, including this writer and his wife, had not forgotten the impact and consequences of the 1971 JVP insurrection, or those of the second in 1988/89. Given that disturbing context, why did he win the 2024 presidential election, albeit by a slim majority? AKD was a toddler during the first insurrection but has readily admitted to playing a part in the second, as a very active member.

I offer my(our) voting pattern as a likely explanation.

In 1977, I rode from Kandapola to Kadadorapitiya in Kotmale, a distance of 50 km in the pouring rain, with my wife on the pillion, and we voted for the UNP candidate for Kotmale. As a working tea planter then, I and many of my colleagues, were deeply disturbed by the intimidatory demonstrations of many ruling SLFP politicians, against the plantation fraternity. That was the last time we voted for a party led by J.R. Jayewardene (JRJ). In 2005, despite serious misgivings, we voted for Ranil Wickremesinghe, as I found Mahinda Rajapaksa’s (MR) racially-charged rhetoric, abhorrent.

In 2009 we opted for Field Marshal, Sarath Fonseka, as a more decent, uncorrupt alternative to Rajapaksa rule, though I gave MR credit for having displayed the political will, for the elimination of the LTTE threat against the Sri Lankan nation-state. In 2015, revolted by the rampant corruption and the aggressively anti-minority stance of the Rajapaksa regime, we chose Maithripala Sirisena and Yahapalanaya.

I even wrote a couple of articles, extolling the virtues of the good governance that was promised. There was hope, for a few weeks, till the “bond scam” ordure hit the proverbial fan and dispelled the euphoria. The promise of good governance was just a cover for the swindles which followed. In 2019 we voted for Sajith Premadasa, as we were convinced, with total justification, that Gotabaya Rajapaksa would be an extension of Rajapksa misrule, despite the contrary opinion of 6.9 million people.

Five years later, along with a few million others, we have placed our faith in the passionate, peasant reformer from Tambuttegama.

Commencing with the JRJ regime, key features of all successive governments have been State corruption, intimidation and assassination of critics, an arrogant disregard for the judiciary which included physical intimidation, the patronage of criminals, and complicity in fraudulent transactions of massive proportions, which depleted State resources, carried out by the State itself or through empowered proxies. These rose to new heights under MR and, under GR, were further compounded by moronic presidential directives, which impoverished the nation through the loss of agricultural land productivity.

The cumulative result of the above was a financial implosion, the summary eviction of GR, and the unexpected installation of Ranil Wickremesinghe (RW), as an unlikely saviour. He did restore a measure of fiscal sanity and provided the nation with some relief, but coupled it with the imposition of unbearable financial hardship on citizens, who were actually the helpless victims of the crimes of the rulers.

Along with the restoration of financial order, RW’s term as president was also signposted by questionable deals, of proportions which relegated the earlier “bond scam” in to insignificance. The Adani wind-power project, the “Visa” scam and the electronic passport deal, are but a few typical examples. Added to that was RW’s arrogant dismissal of Supreme Court directives and his contemptuous rebuttals to legitimate queries, even in Parliament. In an article published in the “Island” newspaper of July 17, 2022, I suggested that RW’s first acts as “appointed president”, may be the “preliminaries to a fascist regime to rival that of the deposed president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa”. I was not wrong.

Thus, despite changes in regimes and rulers, the corrupt and the powerful continued to thrive, proving to an agonized nation that powerful men will always protect powerful men, irrespective of differences in political belief. The people and the faces changed but the status quo, the license to loot and impunity from consequences, has been inviolate.

In the meantime, Sajith Premadasa (SP) despite overbearing, self-adulatory rhetoric , even in relation to the simplest of issues, when actually put to the test, twice demonstrated that he did not have the courage to venture in to unchartered territory. I voiced my feelings in two articles in the ‘Island- (The River That Sajith Premadasa Did Not Cross- May 15 2022 and, The Wickremesinghe Presidency- July 27,.2022). It must have crossed SP’s mind, after the latest loss, that had he seized the moment then, instead of allowing RW to grab it, he would probably be the elected president today.

AKD, our new president, notwithstanding repeated rejection by the electors, has remained firmly grounded to his platform of systems reform, fearlessly naming names and exposing corruption. His campaign message was fluent, direct and simple, and it has been accepted by a reasonable majority (42%) of those who voted, representing an exponential, hardly credible, increase from the paltry 3.16% in the 2019 presidential election.

Patali Ranawaka, parliamentarian, along with many other detractors, has sought to belittle this achievement, suggesting that AKD has been rejected by 58% of the voters. This simplistic arithmetic, if applied to the other two contestants, would suggest that SP has been rejected by 68% and RW by 83%, the latter despite his repeated claims, of having ferried the infant Sri Lankan nation across troubled waters.

Namal Rajapaksa’s (NM) abysmal performance, was a refreshingly unequivocal message from the entire nation, that the Rajapaksa brand of Sinhala-Buddhist centred, militaristic rhetoric, was no longer a marketable product, though related issues were not given central focus during his campaign. NR, stupidly arrogant and myopic, pre-election, spoke loftily, with smug conviction, of furthering the “Mahinda Chinthanaya”, and was rejected by 98% of the electors. RW’s performance too may have been better, had he not surrounded himself with the most corrupt of the Pohottuwa regime. Conversely, the election result reinforces the proven dictum, that the unappetizing RW is a negative influence on any alliance.

Overall, the 2024 election, for the first time since Independence, represents an unexpected maturity of outlook in the Sri Lankan nation. By electing the outsider from Tambuttegama, the voters have broken with the entrenched tradition of family rule, dynastic succession and old-party loyalty, along with the rejection of the tired, obsolete, ideologies of the established parties, parroted, in different ways, by both RW and SP.

The anger of the voters resonated with AKD’s message for a complete systems reform, an end to State corruption, and promised punishment for the corrupt and the criminal. AKD represents the last hope for a nation, nauseated, and impoverished, by the venality of its rulers. It is that message that I responded to, notwithstanding credible apprehensions about possible long-term outcomes of NPP-JVP rule.

His commitment to and focus on, transparency, accountability and social justice, inequalities in health care, educational opportunities, employment creation and environmental sustainability, mirrored the aspirations and concerns of many, especially those at the middle and lower end of the socio-economic ladder. Those comprise clear and optimistic visions for the future, particularly appealing in a time of great national uncertainty. They are also issues which engage the attention of educated youth, who have been frustrated by successive governments.

AKD has fared poorly in the Central Province plantation areas, and the North and the East, where the minorities are pre-dominant. He needs to quickly engage those polities, who have different needs, aspirations and agendas, all legitimate, but denied or subverted by a succession of Sinhala-Buddhist centrist governments. In this area AKD will be treading thin ice, meeting minority aspirations whilst keeping at bay two key JVP/NPP support segments – the retired military and the politically active Buddhist monks. The latter group in particular, is openly committed to Sinhala-Buddhist supremacy and the imposition of a Buddhist seal in the North and the East, engaging for their project the willing support of the forces, the Police Department and even the Department of Archaeology.

Recently, on You-tube, I watched a pre-election rally addressed by AKD, held at the Tambuttegama Central School grounds. He spoke convincingly, and movingly, of the life that he, his family, his fellow villagers and his schoolmates had led. In a matter-of-fact manner, he described the deprivation, the lack of resources and opportunities , and the social and economic marginalization that had been their lot. The audience – his community – listened in pin-drop silence. It was their story as well. Through that deeply personal narrative, he was reflecting the marginal circumstances of 80% of the people of this country, especially in the rural areas. If only a fraction of his manifesto is implemented, it will make life better for that segment and to that end, he needs, and deserves, the mandate that he is seeking.

Features

The 1956 election landslide and SWRD Bandaranaike’s tenure (1956 — 1959)

(Excerpted from Rendering Unto Caesar, memoirs of Bradman Weerakoon)

My acquaintance with S W R D Bandaranaike was only through the press reports of his election campaign. That was before he came to the prime minister’s office in the Fort (now housing the foreign ministry at Republic Square), on an April morning, after the swearing in of his Cabinet at Queen’s House. His eloquence as a speaker, especially his Independence Day speech in 1948, was deeply imprinted in my mind.

Throughout a gruelling campaign he had shown extraordinary skills of perseverance in the face of severe odds, and the ability to persuade large masses of ordinary people to believe in his cause. I wondered how he would be to work with after I had experienced the rather easy going style of Sir John. There was also the serious business to be faced of how soon he would be able to make his election slogan of `Sinhala Only’ as the official language in 24 hours come true?

His accession to power through the general elections of 1956 was as revolutionary and dramatic as it was unexpected by his political opponents and the general public. Most felt that the UNP would return even with a reduced majority. All but the most perceptive, and my friend Howard Wriggins was among them, were convinced that Mr Bandaranaike’s bid for office would end in failure. Indeed as against the forces of capital, both local and foreign, and the mainstream Press which supported the UNP, the pancha maha balavegaya — the five great forces of the Sangha (Buddhist clergy), the vernacular school teachers, the ayurvedic physicians, the farmers and the workers — which he conceptualized and mobilized seemed ephemeral and insubstantial.

Yet he achieved the impossible and in an election over three days, which intended to favour the incumbent government, the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna — MEP (Peoples United Front) managed to win 51 out of the 60 seats they contested. For the record, I should mention that all the ministers of the previous government and Sir John were up for election on the first day while Bandaranaike’s constituency was to poll only on the final day. As it turned out Bandaranaike himself was returned to the Attanagalla seat (where ‘Horagolla Walauwa’ the family home is located) with the highest ever majority in an election. He polled 45,016 votes and had a majority of almost 12,000 over his nearest rival. Both his rivals lost their deposits.

A major factor in the 1956 election was Bandaranaike’s ability to consolidate the opposition to the UNP. He formed a grand coalition with four distinct political groups agreeing to fight the election as a single front on a common program and with the promise of making Sinhala the official language. The MEP was not a political party but a ‘peramuna‘ – a loose, less disciplined entity with a specific purpose, the defeat of the UNP.

Mr Bandaranaike’s Sri Lanka Freedom Party had the largest number of candidates in the MEP — 41 in all. The VLSSP of Mr Philip Gunawardene had five candidates; Bhasha Peramuna (Language Front) of Mr Dahanayake, MP Galle; and a group of eight independents led by Mr I M R A Iriyagolle. There were 60 candidates in all facing a solid UNP phalanx of 76 candidates, many of them sitting members.

At its start the coalition appeared an impractical and unlikely combination. Mr Bandaranaike was known to have an aristocratic background but with vaguely socialist tendencies and a marked sensitivity to Buddhist and Sinhalese religious and language aspirations. Dahanayake had the reputation of being close to the “common man” and had recently moved away from Marxism. Philip Gunawardene was a Marxist who was now convinced about language reform. The question was how they would combine on a common program of social and economic development.

Bandaranaike clinched the issue of a united front against the UNP by entering into a no–contest agreement with the Communist Party and the NLSSP. By this it was ensured that the three parties – MEP, Communist Party and NLSSP would not compete against each other in areas where the UNP was contesting. It raised some difficulties because the latter two parties would have liked to fight the VLSSP – the breakaway group from the LSSP – and it took all of Bandaranaike’s skills of persuasion to sort this out.

Yet, by the look of things at the beginning of the campaign, Bandaranaike’s chances appeared slim. This was especially noticeable when Bernard Aluvihare, former MP from Matale and a joint secretary of the SLFP, deserted Mr Bandaranaike and went over to the UNP on the eve of the election. Yet, the MEP achieved a landslide victory. Once the wind changed, the momentum was unstoppable. The results left us all speechless. In a House of 101, as many as 95 were elected on a first past the post basis, and six to be nominated later to represent interests, mainly ethnic and not represented adequately through election, the MEP won 51 seats and the UNP was reduced to eight.

The NLSSP and C P benefited by the no-contest pact and won 14 and three seats respectively with the redoubtable Dr N M Perera becoming the leader of the opposition. The other parties which returned members were the Federal Party with a significant 10 seats, gaining eight seats over the two they had in the 1952 elections as a result of the major political parties opting for Sinhala as the official language, and the Tamil Congress getting one seat, that of G G Ponnambalam. Eight members came in as independents.

The election was clearly a manifestation of the will of the people for a complete change. Impartial observers asserted that unlike in the previous elections which had resulted in many electoral challenges, in 1956 there had been few instances of bribery, violence or impersonation. Sir John who won at Dodangaslanda – his country borough (the family had been prominent in the graphite industry and the mines were located there) – was one of the very few UNP members who returned in the 1956 change around.

But since he was not even the leader of the opposition – that position having gone to the LSSP chief, N M Perera whose alliance had won 17 seats – he hardly returned to parliament thereafter and soon left the country, virtually retiring to Kent in England where he bought himself an estate called Brogues Wood and on which he lived happily for many years.

Two little incidents which I personally experienced come to mind to illustrate the political culture of the times and the quality of the men who led the country. The first is that of Mr Bandaranaike, on the first day that the new parliament met, going across the floor of the house and patting Sir John on the shoulder to show his appreciation of an election contest well fought. There was absolutely no malice in Mr Bandaranaike’s character. In fact it was Mr Bandaranaike who helped in getting Exchange Control release for the large sum of money Sir John needed for the purchase of Brogues Wood.

The other was my final visit to Kandawala to hand over some personal papers – letters and accounts – which I had found soon after the change of government. I drove in alone in my Morris Minor car and parked in the driveway. Kandawala that morning presented a very different picture from the usual bustle and noise that pervaded the place. There was no one in the verandah and the grand house which had seen such rollicking parties and egg-hopper; breakfasts seemed deserted. On announcing my arrival to an old retainer, I waited for Sir John who came down and sat with me in the verandah.

After thanking me for coming he said that I should not stay long as someone might misunderstand my visit. He then abruptly remarked, “Weerakoon, (he never called me Bradman or Brad) I am like the elephant. I never forget.”

The year 1956 saw the first real change of regime the young state had ever faced. The popular mood was such that everything was to change; the way institutions were run and certainly the persons manning them in particular. The Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (MEP) manifesto promised revolutionary change from the way the UNP had governed the country in the first nine years of freedom. It was not only the language policy, which had priority and an insistent lobby behind it, but everything else that underpinned it.

This was especially so on the cultural side where indigenous forms and practices were set to soon replace the western modes of thought and habit which had gained acceptance in Colombo’s elite circles of society. The banning of horse racing and the consumption of liquor at public functions were two of the most visible of the early measures taken by the new administration to project the new trend. The writing was clear for all to see: the era of the brown sahib as Tarzie Vittachi had told of was coming to an end.

That the government was indeed a peoples’ government was unexpectedly and forcefully expressed when at the opening of Parliament the people in the overflowing public galleries actually invaded the sanctum – the floor of the House itself – and some of them disported themselves in the speaker’s chair.

The change was also to encompass the arena of foreign policy. Bandaranaike and the socialist texture of the Cabinet made it inevitable that the old reliance on the Western alliance and even the Commonwealth had to change.

Very soon, after he took over, the Suez Crisis erupted and Mr Bandaranaike’s address to the General Assembly at the UN made his non-aligned attitude very clear. He made a brilliant exposition of what non-alignment meant, that it was not simply neutrality, not merely sitting on the fence but being committed to the hilt in the defence of peace and freedom. The old order was changing and as Bandaranaike was to remind us, over and over again, it was a time of transition.

Moving the officials of his administration out or around was one of Mr Bandaranaike’s early tasks as prime minister. But he was very conscious of the fact that, barring a very few who were really politically committed, the average bureaucrat mostly carried out faithfully, if he or she was careful and efficient, the biddings of his or her political boss.

Bandaranaike correctly surmised that this would be the same for the new master and therefore was somewhat slower than his followers expected in shifting out those who they felt were `henchmen’ of the former regime. I once heard him explain his alleged dilatoriness over such transfers very clearly and precisely. “I have,” he said, “only just taken control of the wheel. I can’t, my dear fellow,” (he was quite fond of that phrase especially when addressing those he considered slightly below him in intellect) “change all the parts at the same time or I won’t be able to move at all. I will replace

the brake first, the rear wheel next and the carburetor after that, and so on, and soon have a reconditioned model.

But you must give me time”. His timing and logic were perfect and the questioner silenced. But even more important, I thought, was that it showed his essential humanism and liberality. And what would he do with me whom he hardly knew and only as the other civil servant in the office? After an almost two year cadetship (that was what the probation period was called in the CCS) in Anuradhapura and Jaffna, the furthest of the outlying districts, which I had thoroughly enjoyed as a bachelor, outstation life did not now seem particularly enticing. I had got engaged to Damayanthi and the wedding had been fixed for August – only four months away and it would be nice to stay on in Colombo. But I dared not ask.

Finally it was all sorted out to everyone’s satisfaction. Park Nadesan, who had been very close to Sir John, retired on special ‘abolition of office’ terms – which meant he would be entitled to his pension rights though he was leaving before due time. There was to be no post of secretary to the prime minister at least for some time; I stayed on virtually as secretary, but officially as assistant secretary. The formal arrangement was that I would ‘pass the papers’ through the permanent secretary to the ministry of defence and external affairs, the amiable and extremely hard-working Gunasena de Soyza, whom Bandaranaike knew well and had great confidence in.

But as it happened, the prime minister soon began to deal with me directly and, except in the most difficult cases, when I would walk across to the permanent secretary’s room to consult him, the paper flow (or more often chase) was between me and the prime minister at 65, Rosmead Place, his private residence.

I had weathered my first transition. I presumably knew some of the ropes and the new prime minister had thought I could be useful. Since there was not going to be a new secretary appointed officially, I moved into the large and elegantly furnished room which Nadesan had used, overlooking the flamboyant tree-lined Gordon Gardens on Senate Square (now Republic Square). I was to remain there for the next 15 years. I had survived a major political change and not for the first time. I had not taken sides and perhaps Mr Bandaranaike who always did his homework had heard of this. On the other hand it could have been that this first time round I was just too small to be noticed.

From all that the media, the cartoonists and the political writers were saying S W R D Bandaranaike would not only be difficult to get on with but was altogether a very complex personality. D B Dhanapala, the expressive editor of the Lankadipa thought he was ‘an enigma wrapped in a riddle’. Dhanapala’s exasperation in trying to read Mr Bandaranaike’s mind and ways was shared by many others like Tarzie Vittachi6 and Aubrey Collette, the incisive cartoonist.

(To be continued)

Features

I OPPOSE THE PRIME MINISTER, THE MINISTER OF PLANNING AND THE MINISTER OF AGRICULTURE

(Excerpted from Falling leaves, an autobiographical memoir of LC Arulpragasam)

I had no place to go, because I was wedded to the agriculture sector – by my own choosing. Therefore, I was lucky to find a berth as Head of the Agriculture Sector in the Department of National Planning. But I had to pay a career-price for doing this, because it involved my working under a non-civil servant and under someone whom I outranked in the Civil List – which was simply not done in those days.

I also accepted to work in the capacity of Senior Research Officer, which was a post at least two levels below my own rank in the public service. (I always had a penchant toward research – and I must have been fulfilling it at this stage of my life). However, since around 70 per cent of the people were dependent on agriculture, planning its development was the most important job in Sri Lanka at that time. So for me, it was the highest point in my career, although it was ranked in the government service as my lowest!

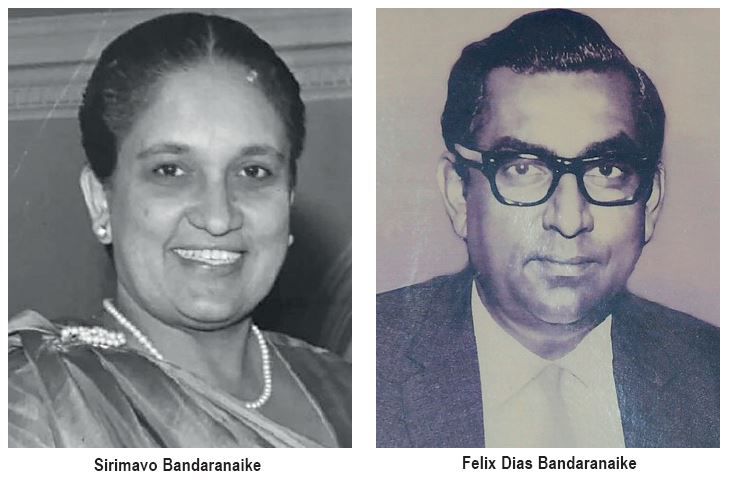

I soon discovered, however, that the Planning Department had absolutely no influence on policy under the government of Mrs. Sirimavo Bandaranaike. It so happened that I knew the Minister of Finance and Planning, Mr. Felix Dias Bandaranaike on a personal basis. For he had been two years my junior at Royal College, and as Head Prefect I had even reported him for a caning for smoking in school. Despite his personal regard for me, I was averse to approaching him directly on policy/political matters, given my personal ethics and Civil Service training of not finding favour with politicians.

I also feared that my work would be lost in the political infighting between Mr. Felix Bandaranaike and Mr. C.P. de Silva, who were both vying for the post of Deputy Prime Minister. Meanwhile, I was growing increasingly frustrated since I knew that I was getting nowhere and had nowhere else to go. For by specializing in the agriculture sector, I had brought myself to a dead end.

Fortunately, things came to a head in 1960, when Mr. Felix Bandaranaike, as Minister of Finance and Planning wished to bring out a three-year development plan together with his budget. He asked me directly at a big meeting of divisional heads whether I could write such a plan for the agriculture sector. I refused – which caused a stir among those present. I boldly said that since I disagreed fundamentally with the Government’s agricultural policies, there was no way in which I could write the proposed Plan. I added that he could transfer me anywhere, but that I would not write endorsing the government’s programs. He got angry and replied that if I presumed to challenge the Government’s policy, I should write and prove it – or I should officially withdraw my statement.

I had to take up his challenge. I was now saddled with an almost impossible task. However, I realized that suddenly and fortuitously, I had been given the chance to lay out my thinking, with the certainty that it would be read. But I had only 10 days in which to do this. Working around the clock with three stenographers and a dictaphone, I was able to produce the needed paper of about 110 pages within 10 days, since I had been working on these issues for some time.

My paper met with amazement and respect from the Minister, Mr. Felix Bandaranaike, an extremely intelligent and arrogant man. After many personal, one-on-one briefings with him, I was able to convince him that the whole agricultural policy and programs were completely uneconomic. I had confronted him in his anger, and I had convinced him that I was right. He now insisted on taking me to the Prime Minister, Mrs. Bandaranaike – to bring about a change in agricultural policy. Now I had to cope with the Prime Minister, who was equally antagonistic.

I remember her opening words: “My husband (the late Mr. Bandaranaike) told me that Mr. C.P. de Silva was the most knowledgeable man in his Cabinet; and now you are telling me that all his policies are wrong”. So I started off with the Prime Minister on an angry note. Since she knew little about the agriculture sector, I had to commence almost daily one-on-one briefings with her at ‘Temple Trees’ (the personal and official residence of the Prime Minister at that time) while she copied notes. After some two weeks of such almost daily, personal briefings at her residence at ‘Temple Trees’ she agreed that radical changes were required in agricultural policy.

She then wanted me to confront Mr. C.P.de Silva, Minister of Agriculture and Lands, who was against all these changes. She summoned a meeting with Mr. C.P. de Silva and all his department heads to a big, high-powered meeting. Fortunately, I had worked with all the Heads of Departments or their Deputies to arrive at the conclusions in my policy paper – some with heated argument, and some with acceptance. The stakes were high; but since I was already on a slippery slope of policy, beyond which any administrator should not dare, I agreed to this too. This seemed to be the only way in which the needed policy changes could be achieved. At issue was early independence on rice – which was mainly imported at that time.

Dead End: My Resignation from the Civil Service

I spent hours agonizing over whether I had a right to intervene in matters of policy. I went ahead with a policy-risk course because I knew that I would be the only person that had the knowledge, the position and the nerve to tell the Prime Minister the truth of our failed agricultural policies. I argued for a policy of agricultural intensification, based on the benefits of the green revolution technologies which were becoming known at that time.

The Government was importing so many millions tons of rice every year. On a rough calculation, we would have lost at least 35,000 million tons of rice (in imports) before the Government finally recognized after 10 years (in 1970) the potential of H4 and H11. (remember the Govi Raja of 1970?) I had confronted the Prime Minster and Minister of Agriculture (Mr..C.P. de Silva) ten years before, in 1960. It was all published in the Short-Term Implementation Program of 1961. Ten years passed before the Ceylon Government actually embraced the green revolution; and this was five years before the Indian Five-Year Plan of 1965 which was credited with introducing the green revolution.

Finally a meeting was called, presided over by the Hon. Prime Minister – at which the Minister of Agriculture and Lands, Mr. C. P. de Silva and all his departmental heads were present. After much argument, when Mr. C. P. de Silva raised his voice against me and abused me, calling me a pothe gura who did not know the facts on the ground. In effect, he called me a liar, challenging the figures that I was using. When I showed him that I was quoting from his own Ministry’s Administration Report, he subsided. The same thing happened four times in the two days of acrimonious meetings. After two days of argument, the Minister finally and resignedly agreed to my proposed policy changes, in front of all his departmental heads.

After one week, however, he decided to renege on our agreement and sought to politically confront the Prime Minister. He threatened to cross the floor with 14 of his parliamentary supporters, which would have led to the fall of Mrs. Bandaranaike’s government. The Prime Minister was forced to back down. She called me to her office to personally apologize to me and offered me “any post you want”. So that was it. All my work – and the risks I had undertaken, had been in vain!

In short, I had struggled to introduce a policy of agricultural intensification against a policy of extensification: that is of opening new land. The short-term benefit of intensification was potentially the doubling of our rice production, by embracing the high-yielding varieties of rice. At issue was millions and millions of bushels of rice – which it took 10 years for the Government to realize. In other words, I was advocating the green revolution in 1960.

Fortunately, this was embodied in The Short-Term Implantation Plan of 1961.. My proposals were buried – because one man chose to play politics, rather than think of the country’s need.. It took 10 years for the new government to recognize the high yielding varieties – and to capitalize on it, by coining the phrase, “Govi Raja”. My fight to get this done under the Bandaranaike government was buried in the dust of history. I think the story would have been different, if I had written this and persuaded Dr, Gamini Corea (whom I knew very well) if he headed the national planning at that time.

I now had nothing to look forward to in the Ceylon Civil Service; I did not want to go into any humdrum administrative post. So I tried desperately to get a posting abroad. Luckily for me, within the next six months I was selected for posts both in the UNDP and the FAO. In 1962, I accepted the FAO position and sent in my letter of resignation from the Civil Service. The Prime Minister sent for me immediately and offered me ‘any post you want’. She also offered me secondment, which had been refused to others in the CCS.

Although I had a permanent job with FAO, I promised the Prime Minister idealistically, that I would come back to work in Sri Lanka as soon as she was in a position to carry out our agreed policy changes. But she was not able to keep her side of the bargain because her Government fell – and the UNP Government took over.

Although I had transgressed the Civil Service tradition of not getting involved in policy matters or with politicians, I need to say this in extenuation of my actions. First, as Head of the Agricultural Sector in the Department of National Planning, it was part of my legitimate duties to evaluate agricultural programs and to suggest alternative policy options; hence, I had not acted beyond my mandate. Secondly, I myself had decided to bow out of my post, rather than get involved in the political rivalry between two senior Ministers.

Thirdly, I had ultimately been ordered (although angrily) by the Minister of Planning (my own Minister) to write and prove my challenge against the agricultural policies of the Government: so I was only obeying orders. Fourthly, I had infringed on policy only because I had known that the country could achieve self-sufficiency in food (that the production of rice could be almost doubled) if only the Minister of Agriculture would agree with the policy recommendations that he himself had agreed to.

I had confronted the Minister of Planning, the Minister of Agriculture and even the Prime Minister, who had all been against my policy proposals.. The price was too high for the country, for me to do otherwise. I think I always knew that there would be a personal price to pay.

Moreover, even though I had spent hours alone with the Prime Minister, I had deliberately kept away from any personal conversation with her. There were many points of personal contacts, which I had deliberately avoided mentioning to her. For instance, my mother-in-law was her close friend and had actually dressed Mrs. Bandaranaike as a bride. Moreover, every time that the Prime Minister went to London, she would bring back presents from my mother-in-law to me, which I had refused to collect from ‘Temple Trees’, because I considered it improper for my mother-in-law to try to ingratiate me with the Prime Minister! Such was the stiff-upper-lip tradition that I had imbibed from the CCS.

Looking back on my ten years in the Ceylon Civil Service (1951 -1961), I can only be thankful for the opportunity that I was given to serve at that time. It is true that I failed to achieve what I set out to do; but this was obviously due to my unrealistic expectations of what could be achieved within an administrative service, rather than any fault of the Civil Service itself. Despite my hard work in the agricultural sector, all my efforts had ended in frustration – due to purely political reasons. It took ten long years before the changes that I had advocated in 1960 were finally embraced by the Government of Sri Lanka. I have no regrets, however, that I tried.

I must also record that I managed to win at least four first places in the Ceylon Civil Service. First, I managed to come first in the Civil Service examination in my year. Second, I was the first Civil Servant to specialize in one sector only – and to ultimately pay a price for doing so. Third, I was the only civil servant, who by choice, agreed to work under a non-civil servant, also someone lower to me in rank in the Civil List. Fourth, I was also the only civil servant (again by my own choice) to go backwards, with my last job being lower than my previous one. So I did hold some records in the CCS – even if only negative ones!

-

Foreign News19 hours ago

Foreign News19 hours agoOne of Ireland’s ‘most wanted’ facing extradition from Dubai

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoADB delegation meets President Dissanayake, pledges continued support for Sri Lanka’s economic development

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoEaster carnage probes and AKD’s call

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoNew start in international relations can be highlighted in Geneva

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoNominations close, NPP and SJB reveal National List nominees

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoTowards a sustainable and secure energy future for Sri Lanka

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDiva commences registrations for 6th Entrepreneurial Skills Development Programme

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSri Lankan worker becomes millionaire doing cleaning jobs in Australia