Features

Deshabandu Dr. T. Publis Silva Longest-standing Sri Lankan Chef and National Treasure

PLACES, PEOPLE & PASSIONS (3Ps)

Part six

Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

chandij@sympatico.ca

Profile

Publis is a household name in Sri Lanka as a chef, author, TV personality, and to many, a national treasure. He joined Mount Lavinia Hotel in 1956 as a kitchen labourer. In the early-1970s he was trained by the Hyatt Corporation in USA, who managed the hotel at that time. Publis was promoted as the Executive Chef in 1984, and then promoted as the Director Culinary Affairs & Promotions in 2003, a position he has held for 20 years. During his 67-year long career at Mount Lavinia Hotel, he also did a stint in the Maldives and was responsible for organizing numerous Sri Lankan food festivals and promotions in 33 countries.

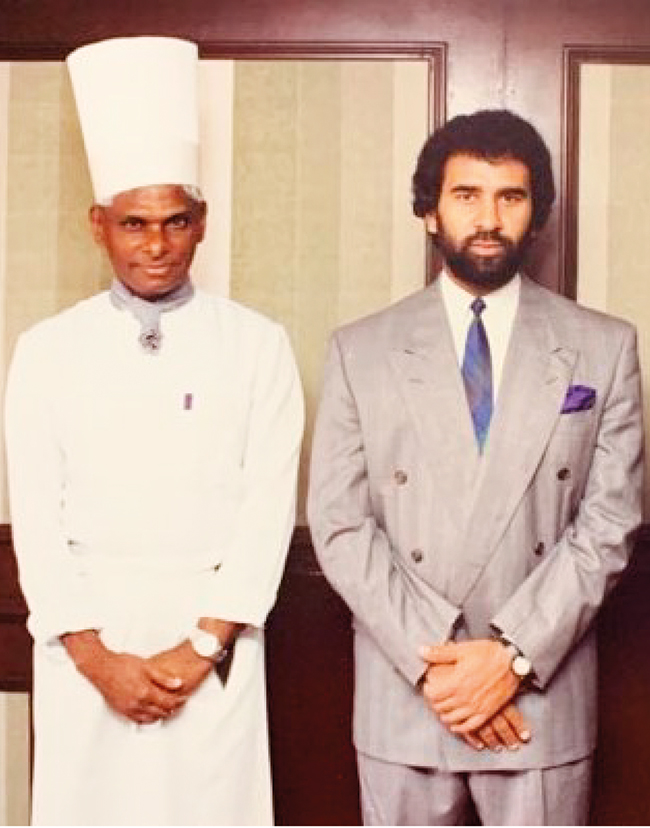

I first met Publis Silva in 1972 at the Mount Lavinia Hyatt Hotel, when he was the Assistant Chef, and I was a Trainee Waiter. The next time I met him was in 1990 and we worked closely as the Executive Chef and the General Manager. We then co-wrote a book which was the maiden attempt in book publishing by each of us. After I left Sri Lanka in 1994 we kept in touch, and he made sure that I received a signed copy of each of his books. Today I am his proudest fan.

First Impressions in 1972

By early 1970s Mount Lavinia Hotel (MLH) became the first ever hotel in Ceylon to get an international brand name. Hyatt Hotels Corporation in USA managed MLH. At that time, to graduate from the Ceylon Hotel School (CHS), each student had to do two mandatory co-op placements or in-service periods. Four of my CHS batchmates and I were fortunate to be allocated to MLH for our first in-service in 1972/1973 tourist season.

After the American General Manager from Hyatt corporation, Robert McFadden, met with us on our first day, we were introduced to a few key members of the hotel team, including Publis Silva, who was the Assistant Chef of MLH at that time. He was in his mid-thirties, and I was in my late teens.

My first impression of Publis was special. By then he had worked in the MLH kitchens for 16 years and gradually had risen to the second in command position of the kitchen department. He had also undergone training with three European Executive Chefs sent to MLH by Hyatt.

After the departure of those expatriate chefs, Just before the 1972/1973 tourist season, the hotel had appointed an Acting Executive Chef, a young Sri Lankan from a prominent family in Colombo, who was trained by Publis. I watched how Publis treated this young chef with respect and fully supporting him. Publis is a professional who always respected superiors, irrespective of their level of experience or knowledge.

Christmas of 1972

I remember Publis leading the kitchen brigade in preparing the Christmas Eve dinner in 1972. I sought Chef Publis’s help in understanding some of the dishes I was not familiar with. Despite being very busy that day Publis went into detailed explanations in Sinhala. He wanted us to be well-informed Trainee Waiters. With the additional knowledge I gained by talking with Publis, I managed to earn some extra tips that evening. He was always very helpful and friendly.

Working in the same team in 1990

Eighteen years later In 1990, when I returned to MLH as the General Manager, Publis worked on my team as the Executive Chef. I quickly appreciated that Publis is a great asset to the hotel. Whatever task I delegated to him was done promptly and efficiently. His knowledge of the history of MLH, and the culture of the company were useful to me in settling down in my new and the last job position in Sri Lanka.

Publis was the first to come to work every day and did the longest shift, among all managers. He hardly took any off days, and never needed any sick leave. He was always healthy and fit as a fiddle. MLH was and is his temple. When we worked together on new à la carte menus, I realized that Publis was also open to new suggestions. When the owners of MLH agreed to my suggestion to establish an International Hotel School (IHS) within MLH, Publis became a big supporter of my vision.

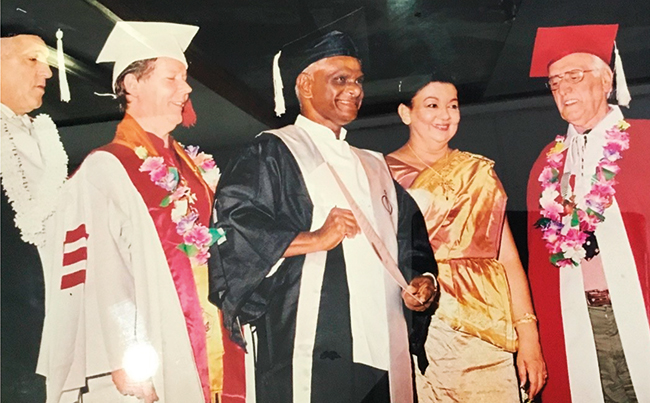

Establishing IHS in 1991

IHS was launched with a bang in 1991. It was an immediate success with five international accreditations and pathways and students from five countries. I worked as the Managing Director of IHS and Publis worked as the Adviser in Culinary courses. We also established a Program Advisory Committee with experts from ten countries and introduced for the first time in Sri Lanka, ‘Hotel Administration’ seminars for senior managers. At the end of the 22-week culinary program of IHS, Publis choreographed a classical menu with 13 dishes, cooked, and served by IHS students. We invited all the Executive Chefs of five-star hotels in Colombo for this meal.

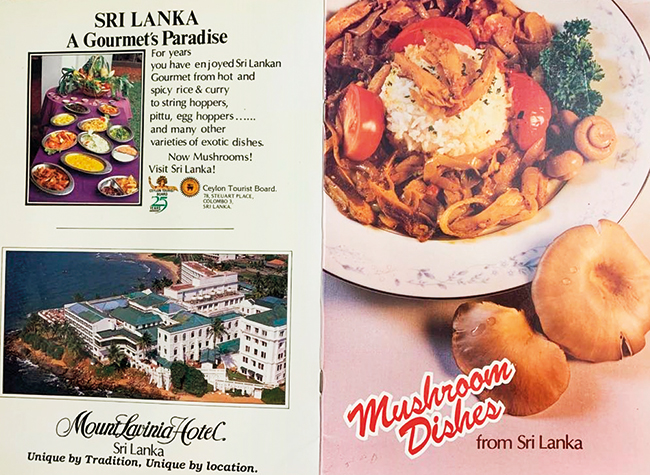

Getting into Book Publishing in 1992

One day Publis came to me with a suggestion for a new food promotion. “Sir, how about doing a mushroom promotion? We have a wide variety of mushrooms in Sri Lanka, but unknown to many.” After a brief discussion, I was very impressed with Publis’s wide knowledge of the subject. I learnt a lot from him about mushrooms. “OK, Chef. Let’s move forward with your suggestion. Can you produce a small booklet about mushrooms?” I planted a seed in his mind. Within a few days he found a sponsor to print the booklet. Publis was always prompt in making things happen.

The ‘Mushroom Week’ of MLH was held from 24th to 30th April 1991, in association with the Ceylon Tourist Board, the Mushroom Development and Training Centre and Export Development Board. The booklet compiled by Publis was sold for US$ 2.50 a copy. That was the beginning of the most outstanding journey of writing and publishing books on Sri Lankan gastronomy, by the longest-standing Sri Lanka chef.

After the success of the mushroom promotion, I wanted to explore other possibilities to showcase Publis’s amazing research and knowledge about local ingredients and traditional dishes. He was doing in-depth research on dishes specifically prepared for the royal families of the Kandyan kingdom, prior to 1815. However, when I suggested that he should author a ground-breaking Sri Lankan cookbook, Publis declined citing his lack of knowledge of the English language. I said to him, “why don’t you write the book in Sinhala?”, but he was too shy to undertake such a project.

I did not give up. I twisted his arm occasionally and gently, but it took a year before he agreed, on one condition. That was: I must work as his co-author. I agreed, but he did most of the work. My key contributions were writing a short introduction and finding a publisher. In 1992 we published ‘Sinhala Bojana’ in Sinhala and in 1993 we published ‘Traditional Sri Lankan Food’ in English.

After that, I left Sri Lanka, and we did not collaborate for scholarly publications, but proceeded with our own subjects of interest. Publis continued in creating the greatest volume of books dedicated to Sri Lankan food. I focused mainly on international hospitality management, tourism, and innovation. With those two books, both Publis and I commenced a 31-year journey of book writing and publishing, cumulatively totalling 47 books, so far…

Best Manager in 1993

The Chairman of MLH, Mr. Sanath Ukwatte and I decided to select the ‘Best Manager’ of the hotel in early 1993. Being such a generous person, the Chairman decided to present a car to the winner. We had an excellent team at MLH, but our choice was easy. We picked Publis and rewarded him with the prize of a car.

After my three-year expatriate contract, I left MLH in December 1993 and a few months later I left Sri Lanka for good to focus on my international career. On my last day at MLH, while my family was packing our bags to leave, Publis called me. When he said, “Sir, may I see you with our farewell present?”, I told him, “Chef, the management team already presented me with presents, last evening during the farewell party.” “No Sir, I want to come with my senior team of Chefs to give you something special.” Within a few minutes Publis and his team of 12 Sous Chefs and Chef de Partie came to my apartment at MLH and presented me with an engraved plaque.

A Loyal and Grateful Friend from 1994 to 2023

After 1994 I have stayed at MLH many times as a guest during family holidays, doing consulting assignments, presenting leadership development seminars, and doing a few IHS re-structuring projects. I chose MLH as the venue for two of my most important life events – the home coming wedding reception for my wife in 1999, and my 50th birthday party in 2003. On those two occasions, I never looked at the menu. When Publis asked me what I want in the menu I simply told him, “You decide on the menu, Chef. Anything good for you is good for me.” On both these special occasions, just as I expected, Chef Publis exceeded my expectations.

When it comes to memorable and magical events, there is no better venue than MLH, and no better Chef than Publis. MLH has been my home away from home during the last 30 years. Meanwhile, Publis made sure that I received a signed copy of each of his books. Every time he was generous with his appreciation and thanks for getting him to write and publish in 1992. Despite my repeated reminders to him that I don’t deserve such praise, Publis has been disobedient in that regard.

On April 20, 2023, while on a seven-week holiday in Sri Lanka I received a message through a friend that Dr. Publis Silva wants to see me before my departure. When he heard that I ws being hosted to dinner at Ellen’s Place – an inn in Colombo eight, by a few hotelier friends, Publis showed up early. Unfortunately, my previous engagement was delayed by an hour, and poor Publis stayed on patiently in spite of his family having a religious ceremony at his house on the same evening.

After a brief chat he presented me with a signed copy of his latest book: ‘MAHASUPAWAMSAYA: The Great Chronicle of Sri Lankan Culinary Art’. I glance through the book to find that it has a total of 1,074 pages! Chef Publis never ceased to amaze me!

I was deeply touched with the message that he hand wrote on the front page of the book he presented to me. It said: “This is presented to you, who supported me and encouraged me to write books.” For over 50 years, the privilege has been mine to get many opportunities to associate with the greatest Sri Lankan Chef, who is indeed a National Treasure.

Questions and Answers

After I returned to Canada, soon after our last meeting in 2023, I sent the following ten questions to Deshabandu Dr. T. Publis Silva:

Q: Out of all the places you have visited in Sri Lanka and overseas, what is your favourite and most interesting place?

A: Mount Lavinia Hotel and I are inseparable. Hence, I can proudly say that my favourite place out of every country and city I have ever been to is, Mount Lavinia (Galkissa).

Q: You have inspired generations of culinary professionals. Thinking of the other side of the coin, in your career, who inspired you most?

A: In 1950s, the first à la carte restaurant in Ceylon was opened at MLH and its kitchen was developed and managed by Bass (Head Cook) R. K. M. Silva.He was a real inspiration for me and taught me a lot of valuable lessons. After his passing, to pay my respects, I created a dish named after him called “Seer RKM.” and placed it in menus across the hotel, as well as in my books, especially the Sinhalese Practical Cookery book which was used in many culinary schools and institutions across Sri Lanka.

Q: At the present time, apart from cooking, researching, and writing, what is your key passion in life?

A: To make food that is medicine is my current key passion and goal in life. This mainly includes using the abundant varieties of fruits, vegetables, legumes, seeds, cereals, and beans to dishes which are brimming with health properties. To add into it, the art of putting love and attention into the food we make while being mindful in the whole cooking process ensures we keep the maximum nutrition value of the food while preserving the flavour and the aroma of the food.

In the modern world, non-contagious diseases such as diabetes and cancer are more prevalent and deadly and eating the right type of food can ensure we can prevent or control these diseases.

Q: Can you tell our readers about your interesting adventures before joining MLH in 1956?

A: As a kid of six years old, I used to go to the beach in Ratgama with my friends and the entire beach was ours to explore. I remember we used to pluck coconuts from the trees, husk and crack the shells and then eat the kernel. One day when a piece of kernel fell in the sand, I washed it with sea water. When I ate it I experienced a better taste. This was one of my initial curiosities into the culinary world.

When I was around 20 years old, without a job and after marriage, I used to push carts in Colombo to earn a living. My passengers usually head for the market to sell produce and usually there were leftovers. I used to pick them up and then cook dishes from those.

I remember the first time I used a leftover karawala (dry salted fish) bone in a vegetable curry, the flavour made me feel like I was in heaven and to-date, that was the best food I remember having experienced. These are a few of my stories about the hardships I faced and how I developed a passion for cooking.

Q: In 1970 when MLH became the first hotel in Sri Lanka to be managed by an international hotel chain, what did you learn from the Hyatt Corporation, USA?

A: Hyatt Corporation brought in international chefs and I with all our MLH kitchen staff learned a lot from them. I especially learned about butchery and meat from French, German and Swiss chefs and I respect them for further igniting my passion to research about all kinds of food.

Q: Can you give the readers some numbers from your 67-year long career in culinary arts – total number of books, TV shows, food festivals, weddings catered for (including BMICH) etc.?

A: I have written 20 books, attended a countless number of TV shows, and I remember celebrating the 10,000th wedding catered when Dr. Chandana Jayawardena was the General Manager of MLH. In 1992, as the long-standing catering partner of BMICH – national convention centre, MLH did the catering for the largest wedding to be held in Sri Lanka. We prepared and served 2,400 invitees a sit-down Biriyani dinner within 90-minutes. I must mention that Dr. Chandana Jayawardena was also the person who pushed me into writing more books and my first book was written along with his collaboration. I have also visited 33 countries to promote Sri Lankan food and culture.

Q: You have recorded numerous achievements, including two Guinness World Records, an honorary doctorate, and the national award of Deshabandu. What do you consider as your greatest achievement during the last 77 years?

A: The greatest achievement for me was the Guiness World Record for the world’s largest milk rice ever made. It contained 1000kg of rice and 2000kg of coconuts. During that huge undertaking, it felt like I was the conductor of a symphony orchestra with 120 chefs. They were ready to obey each command, I told them when to add the rice, when to add the milk, when to add the water, when to lower the fire, and finally, the end-product which was 62 feet long and five feet wide was a world record breaking milk rice with a consistent flavour and each piece was enjoyed by those who attended to witness the world record.

Q: Your book MAHASUPAVANSHAYA, has over 1,000 pages and you led a large team of researchers in producing this book. Tell our readers more about that remarkable process ?

A: It took me and my team over 30 years to complete the book, we went across Sri Lanka gathering a vast volume of information and our research took us to some parts in Africa as well. Professors and students from Sri Jayewardenepura University helped me a lot along with a team of 12 chefs from MLH. During my research, while learning about the history of culinary arts in Sri Lanka, I learned that during the time of King Dutugamunu, they used a Stone Oruwa (a stone boat) filled it with water, filled it with heated rocks and that brought the water to a heated temperature, which ultimately made the Stone Oruwa act as a chafing dish to keep any food containers placed inside hot. This was the first recorded usage of a chafing dish in the world.

Q: What does a normal day of the Director Culinary Affairs and Promotions of MLH, look like?

A: The first thing I do when I arrive at my office in the morning is to search for new innovations in the culinary field. I keep myself as a student and learn new things every day. I ensure that anything I learn I teach to the next generation and then search for new innovations again. This cycle encapsulates my normal day as the Director of Culinary Affairs and Promotions. For example, my thinking of culinary innovation led me to learn that, if we take the Kos Tree (Jak Fruit Tree), there are abundant uses we have, and each piece of the entire Kos Tree can be used in some culinary way.

Q: What is your advice to young chefs who dream of having a long career in culinary arts?

A: In the world, I believe that the best thing someone can learn is to cook, I ask of the entire younger generation to learn cooking as I believe that if anyone learns about cooking, it will be one of the most important and useful skills acquired in life.

Next week, 3Ps will feature a university professor who is also a leader in tourism in Sri Lanka…

Features

Reconciliation: Grand Hopes or Simple Steps

In politics, there is the grand language and the simple words. As they say in North America, you don’t need a $20-word or $50-word where a simple $5-world will do. There is also the formal and the functional. People of different categories can functionally get along without always needing formal arrangements involving constitutional structures and rights declarations. The latter are necessary and needed to protect the weak from the bullies, especially from the bullying instruments of the state, or for protecting a small country from a Trump state. In the society at large, people can get along in their daily lives in spite of differences between them, provided they are left alone without busybody interferences.

There have been too many busybody interferences in Sri Lanka in all the years after independence, so much so they exploded into violence that took a toll on everyone for as many as many as 26 (1983-2009) years. The fight was over grand language matters – selective claims of history, sovereignty assertions and self-determination counters, and territorial litigations – you name it. The lives of ordinary people, even those living in their isolated corners and communicating in the simple words of life, were turned upside down. Ironically in their name and as often in the name of ‘future generations yet unborn’ – to recall the old political rhetoric always in full flight. The current American anti-abortionists would have loved this deference to unborn babies.

At the end of it all came the call for Reconciliation. The term and concept are a direct outcome of South Africa’s post-apartheid experience. Quite laudably, the concept of reconciliation is based on choosing restorative justice as opposed to retributive justice, forgiveness over prosecution and reparation over retaliation. The concept was soon turned into a remedial toolkit for societies and polities emerging from autocracies and/or civil wars. Even though, South Africa’s apartheid and post-apartheid experiences are quite unique and quite different from experiences elsewhere, there was also the common sharing among them of both the colonial and postcolonial experiences.

The experience of facilitating and implementing reconciliation, however, has not been wholly positive or encouraging. The results have been mixed even in South Africa, even though it is difficult to imagine a different path South Africa could have taken to launch its post-apartheid era. There is no resounding success elsewhere, mostly instances of non-starters and stallers. There are also signs of acknowledgement among activists and academics that the project of reconciliation has more roadblocks to overcome than springboards for taking off.

Ultimately, if state power is not fully behind it the reconciliation project is not likely to take off, let alone succeed. The irony is that it is the abuse of state power that created the necessity for reconciliation in the first place. Now, the full blessing and weight of state power is needed to deliver reconciliation.

Sri Lanka’s Reconciliation Journey

After the end of the war in 2009, Sri Lanka was an obvious candidate for reconciliation by every objective measure or metric. This was so for most of the external actors, but there were differences in the extent of support and in their relationship with the Sri Lankan government. The Rajapaksa government that saw the end of the war was clearly more reluctant than enthusiastic about embarking on the reconciliation journey. But they could not totally disavow it because of external pressure. The Tamil political leadership spurred on by expatriate Tamils was insistent on maximalist claims as part of reconciliation, with a not too subtle tone of retribution rather than restoration.

As for the people at large, there was lukewarm interest among the Sinhalese at best, along with strident opposition by the more nationalistic sections. The Tamils living in the north and east had too much to do putting their shattered lives together to have any energy left to expend on the grand claims of reconciliation. The expatriates were more fortuitously placed to be totally insistent on making maximalist claims and vigorously lobbying the western governments to take a hardline against the Sri Lankan government. The singular bone of contention was about alleged war crimes and their investigation, and that totally divided the political actors over the very purpose of reconciliation – grand or simple.

By far the most significant contribution of the Rajapaksa government towards reconciliation was the establishment of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) that released its Report and recommendations on December 16, 2011, which turned out to be the 40th anniversary of the liberation of Bangladesh. I noted the irony of it in my Sunday Island article at that time.

Its shortcomings notwithstanding, the LLRC Report included many practical recommendations, viz., demilitarization of the North and East; dismantling of High Security Zones and the release of confiscated houses and farmland back to the original property owners; rehabilitation of impacted families and child soldiers; ending unlawful detention; and the return of internally displaced people including Muslims who were forced out of Jaffna during the early stages of the war. There were other recommendations regarding the record of missing persons and claims for reparation.

The implementation of these practical measures was tardy at best or totally ignored at worst. What could have been a simple but effective reconciliation program of implementation was swept away by the assertion of the grand claims of reconciliation. In the first, and so far only, Northern Provincial Council election in 2013, the TNA swept the board, winning 30 out of 38 seats in provincial council. The TNA’s handpicked a Chief Minister parachuted from Colombo, CV Wigneswaran, was supposed to be a bridge builder and was widely expected to bring much needed redress to the people in the devastated districts of the Northern Province. Instead, he wasted a whole term – bandying the claim of genocide and the genealogy of Tamil. Neither was his mandated business, and rather than being a bridge builder he turned out to be a total wrecking ball.

The Ultimate Betrayal

The Rajapaksa government mischievously poked the Chief Minister by being inflexible on the meddling by the Governor and the appointment of the Provincial Secretary. The 2015 change in government and the duopolistic regime of Maithripala Sirisena as President and Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister brought about a change in tone and a spurt for the hopes of reconciliation. In the parliamentary contraption that only Ranil Wickremesinghe was capable of, the cabinet of ministers included both UNP and SLFP MPs, while the TNA was both a part of the government and the leading Opposition Party in parliament. Even the JVP straddled the aisle between the government and the opposition in what was hailed as the yahapalana experiment. The experiment collapsed even as it began by the scandal of the notorious bond scam.

The project of reconciliation limped along as increased hopes were frustrated by persistent inaction. Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera struck an inclusive tone at the UNHRC and among his western admirers but could not quite translate his promises abroad into progress at home. The Chief Minister proved to be as intransigent as ever and the TNA could not make any positively lasting impact on the one elected body for exercising devolved powers, for which the alliance and all its predecessors have been agitating for from the time SJV Chelvanayakam broke away from GG Ponnambalam’s Tamil Congress in 1949 and set up the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kadchi aka the Federal Party.

The ultimate betrayal came when the TNA acceded to the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe government’s decision to indefinitely postpone the Provincial Council elections that were due in 2018, and let the Northern Provincial Council and all other provincial councils slip into abeyance. That is where things are now. There is a website for the Northern Provincial Council even though there is no elected council or any indication of a date for the long overdue provincial council elections. The website merely serves as a notice board for the central government’s initiatives in the north through its unelected appointees such as the Provincial Governor and the Secretary.

Yet there has been some progress made in implementing the LLRC recommendations although not nearly as much as could have been done. Much work has been done in the restoration of physical infrastructure but almost all of which under contracts by the central government without any provincial participation. Clearing of the land infested by landmines is another area where there has been much progress. While welcoming de-mining, it is also necessary to reflect on the madness that led to such an extensive broadcasting of landmines in the first place – turning farmland into killing and maiming fields.

On the institutional front, the Office on Missing Persons (OMP) and the Office for Reparations have been established but their operations and contributions are yet being streamlined. These agencies have also been criticized for their lack of transparency and lack of welcome towards victims. While there has been physical resettlement of displaced people their emotional rehabilitation is quite a distance away. The main cause for this is the chronically unsettled land issue and the continuingly disproportionate military presence in the northern districts.

(Next week: Reconciliation and the NPP Government)

by Rajan Philips

Features

The Rise of Takaichi

Her victory is remarkable, and yet, beyond the arithmetic of seats, it is the audacity, unpredictability, and sheer strategic opportunism of Sanae Takaichi that has unsettled the conventions of Japanese politics. Japan now confronts the uncharted waters of a first female prime minister wielding a super-majority in the lower house, an electoral outcome amplified by the external pressures of China’s escalating intimidation. Prior to the election, Takaichi’s unequivocal position on Taiwan—declaring that a Chinese attack could constitute an existential threat justifying Japan’s right to collective self-defence—drew from Beijing a statement of unmistakable ferocity: “If Japan insists on this path, there will be consequences… heads will roll.” Yet the electorate’s verdict on 8 February 2026 was unequivocal: a decisive rejection of external coercion and an affirmation of Japan’s strategic autonomy. The LDP’s triumph, in this sense, is less an expression of ideological conformity than a popular sanction for audacious leadership in a period of geopolitical uncertainty.

Takaichi’s ascent is best understood through the lens of calculated audacity, tempered by a comprehension of domestic legitimacy that few of her contemporaries possess. During her brief tenure prior to the election, she orchestrated a snap lower house contest merely months after assuming office, exploiting her personal popularity and the fragility of opposition coalitions. Unlike predecessors who relied on incrementalism and cautious negotiation within the inherited confines of party politics, Takaichi maneuvered with precision, converting popular concern over regional security and economic stagnation into tangible parliamentary authority. The coalescence of public anxiety, amplified by Chinese threats, and her own assertive persona produced a political synergy rarely witnessed in postwar Japan.

Central to understanding her political strategy is her treatment of national security and sovereignty. Takaichi’s articulation of Japan’s response to a hypothetical Chinese aggression against Taiwan was neither rhetorical flourish nor casual posturing. Framing such a scenario as a “survival-threatening situation” constitutes a profound redefinition of Japanese strategic calculus, signaling a willingness to operationalise collective self-defence in ways previously avoided by postwar administrations. The Xi administration’s reaction—including restrictions on Japanese exports, delays in resuming seafood imports, and threats against commercial and civilian actors—unintentionally demonstrated the effectiveness of her approach: coercion produced cohesion rather than capitulation. Japanese voters, perceiving both the immediacy of threat and the clarity of leadership, rewarded decisiveness. The result was a super-majority capable of reshaping the constitutional and defence architecture of the nation.

This electoral outcome cannot be understood without reference to the ideological continuity and rupture within the LDP itself. Takaichi inherits a party long fractured by internal factionalism, episodic scandals, and the occasional misjudgment of public sentiment. Yet her rise also represents the maturation of a distinct right-of-centre ethos: one that blends assertive national sovereignty, moderate economic populism, and strategic conservatism. By appealing simultaneously to conservative voters, disillusioned younger demographics, and those unsettled by regional volatility, she achieved a political synthesis that previous leaders, including Fumio Kishida and Shigeru Ishiba, failed to materialize. The resulting super-majority is an institutional instrument for the pursuit of substantive policy transformation.

Takaichi’s domestic strategy demonstrates a sophisticated comprehension of the symbiosis between economic policy, social stability, and political legitimacy. The promise of a two-year freeze on the consumption tax for foodstuffs, despite its partial ambiguity, has served both as tangible reassurance to voters and a symbolic statement of attentiveness to middle-class anxieties. Inflation, stagnant wages, and a protracted demographic decline have generated fertile ground for popular discontent, and Takaichi’s ability to frame fiscal intervention as both pragmatic and responsible has resonated deeply. Similarly, her attention to underemployment, particularly the activation of latent female labour, demonstrates an appreciation for structural reform rather than performative gender politics: expanding workforce participation is framed as an economic necessity, not a symbolic gesture.

Her approach to defence and international relations further highlights her strategic dexterity. The 2026 defence budget, reaching 9.04 trillion yen, the establishment of advanced missile capabilities, and the formation of a Space Operations Squadron reflect a commitment to operationalising Japan’s deterrent capabilities without abandoning domestic legitimacy. Takaichi has shown restraint in presentation while signaling determination in substance. She avoids ideological maximalism; her stated aim is not militarism for its own sake but the assertion of national interest, particularly in a context of declining U.S. relative hegemony and assertive Chinese manoeuvres. Takaichi appears to internalize the balance between deterrence and diplomacy in East Asian geopolitics, cultivating both alliance cohesion and autonomous capability. Her proposed constitutional revision, targeting Article 9, must therefore be read as a calibrated adjustment to legal frameworks rather than an impulsive repudiation of pacifist principles, though the implications are inevitably destabilizing from a regional perspective.

The historical dimension of her politics is equally consequential. Takaichi’s association with visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, her questioning of historical narratives surrounding wartime atrocities, and her engagement with revisionist historiography are not merely symbolic gestures but constitute deliberate ideological positioning within Japan’s right-wing spectrum.

Japanese politics is no exception when it comes to the function of historical narrative as both ethical compass and instrument of legitimacy: Takaichi’s actions signal continuity with a nationalist interpretation of sovereignty while asserting moral authority over historical memory. This strategic management of memory intersects with her security agenda, particularly regarding Taiwan and the East China Sea, allowing her to mobilize domestic consensus while projecting resolve externally.

The Chinese reaction, predictably alarmed and often hyperbolic, reflects the disjuncture between external expectation and domestic reality. Beijing’s characterization of Takaichi as an existential threat to regional peace, employing metaphors such as the opening of Pandora’s Box, misinterprets the domestic calculation. Takaichi’s popularity did not surge in spite of China’s pressure but because of it; the electorate rewarded the demonstration of agency against perceived coercion. The Xi administration’s misjudgment, compounded by a declining cadre of officials competent in Japanese affairs, illustrates the structural asymmetries that Takaichi has been able to exploit: external intimidation, when poorly calibrated, functions as political accelerant. Japan’s electorate, operating with acute awareness of both historical precedent and contemporary vulnerability, effectively weaponized Chinese miscalculation.

Fiscal policy, too, serves as an instrument of political consolidation. The tension between her proposed consumption tax adjustments and the imperatives of fiscal responsibility illustrates the deliberate ambiguity with which Takaichi operates: she signals responsiveness to popular needs while retaining sufficient flexibility to negotiate market and institutional constraints. Economists note that the potential reduction in revenue is significant, yet her credibility rests in her capacity to convince voters that the measures are temporary, targeted, and strategically justified. Here, the interplay between domestic politics and international market perception is critical: Takaichi steers both the expectations of Japanese citizens and the anxieties of global investors, demonstrating a rare fluency in multi-layered policy signaling.

Her coalition management demonstrates a keen strategic instinct. By maintaining the alliance with the Japan Innovation Party even after securing a super-majority, she projects an image of moderation while advancing audacious policies. This delicate balancing act between consolidation and inclusion reveals a grasp of the reality that commanding numbers in parliament does not equate to unfettered authority: in Japan, procedural legitimacy and coalition cohesion remain crucial, and symbolic consensus continues to carry significant cultural and institutional weight.

Yet, perhaps the most striking element of Takaichi’s victory is the extent to which it has redefined the interface between domestic politics and regional geopolitics. By explicitly linking Taiwan to Japan’s collective self-defence framework, she has re-framed public understanding of regional security, converting existential anxiety into political capital. Chinese rhetoric, at times bordering on the explicitly menacing, highlights the efficacy of this strategy: the invocation of direct consequences and the threat of physical reprisal amplified domestic perceptions of threat, producing a rare alignment of public opinion with executive strategy. In this sense, Takaichi operates not merely as a domestic politician but as a conductor of transnational strategic sentiment, demonstrating an acute awareness of perception, risk, and leverage that surpasses the capacity of many predecessors. It is a quintessentially Machiavellian maneuver, executed with Japanese political sophistication rather than European moral theorisation. Therefore, the rise of Sanae Takaichi represents more than the triumph of a single politician: it signals a profound re-calibration of the Japanese political order.

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa

Features

Rebuilding Sri Lanka’s Farming After Cyclone Ditwah: A Reform Agenda, Not a Repair Job

Three months on (February 2026)

Three months after Cyclone Ditwah swept across Sri Lanka in late November 2025, the headlines have moved on. In many places, the floodwaters have receded, emergency support has reached affected communities, and farmers are doing what they always do, trying to salvage what they can and prepare for the next season. Yet the most important question now is not how quickly agriculture can return to “normal”. It is whether Sri Lanka will rebuild in a way that breaks the cycle of risks that made Ditwah so devastating in the first place.

Ditwah was not simply a bad storm. It was a stress test for our food system, our land and water management, and the institutions meant to protect livelihoods. It showed, in harsh detail, how quickly losses multiply when farms sit in flood pathways, when irrigation and drainage are designed for yesterday’s rainfall, when safety nets are thin, and when early warnings do not consistently translate into early action.

In the immediate aftermath, the damage was rightly measured in flooded hectares, broken canals and damaged infrastructure, and families who lost a season’s worth of income overnight. Those impacts remain real. But three months on, the clearer lesson is why the shock travelled so far and so fast. Over time, exposure has become the default: cultivation and settlement have expanded into floodplains and unstable slopes, driven by land pressure and weak enforcement of risk-informed planning. Infrastructure that should cushion shocks, tanks, canals, embankments, culverts, too often became a failure point because maintenance has lagged and design standards have not kept pace with extreme weather. At farm level, production risk remains concentrated, with limited diversification and high sensitivity to a single event arriving at the wrong stage of the season. Meanwhile, indebted households with delayed access to liquidity struggled to recover, and the information reaching farmers was not always specific enough to prompt practical decisions at the right time.

If Sri Lanka takes only one message from Ditwah, it should be this: recovery spending, by itself, is not resilience. Rebuilding must reduce recurring losses, not merely replace what was damaged. That requires choices that are sometimes harder politically and administratively, but far cheaper than repeating the same cycle of emergency, repair, and regret.

First, Sri Lanka needs farming systems that do not collapse in an “all-or-nothing” way when water stays on fields for days. That means making diversification the norm, not the exception. It means supporting farmers to adopt crop mixes and planting schedules that spread risk, expanding the availability of stress-tolerant and short-duration varieties, and treating soil health and field drainage as essential productivity infrastructure. It also means paying far more attention to livestock and fisheries, where simple measures like safer siting, elevated shelters, protected feed storage, and better-designed ponds can prevent avoidable losses.

Second, we must stop rebuilding infrastructure to the standards of the past. Irrigation and drainage networks, rural roads, bridges, storage facilities and market access are not just development assets; they are risk management systems. Every major repair should be screened through a simple question: will this investment reduce risk under today’s and tomorrow’s rainfall patterns, or will it lock vulnerability in for the next 20 years? Design standards should reflect projected intensity, not historical averages. Catchment-to-field water management must combine engineered solutions with natural buffers such as wetlands, riparian strips and mangroves that reduce surge, erosion and siltation. Most importantly, hazard information must translate into enforceable land-use decisions, including where rebuilding should not happen and where fair support is needed for people to relocate or shift livelihoods safely.

Third, Sri Lanka must share risk more fairly between farmers, markets and the state. Ditwah exposed how quickly a climate shock becomes a debt crisis for rural households. Faster liquidity after a disaster is not a luxury; it is the difference between recovery and long-term impoverishment. Crop insurance needs to be expanded and improved beyond rice, including high-value crops, and designed for quicker payouts. At the national level, rapid-trigger disaster financing can provide immediate fiscal space to support early recovery without derailing budgets. Public funding and concessional climate finance should be channelled into a clear pipeline of resilience investments, rather than fragmented projects that do not add up to systemic change.

Fourth, early warning must finally become early action. We need not just better forecasts but clearer, localised guidance that farmers can act on, linked to reservoir levels, flood risk, and the realities of protecting seed, inputs and livestock. Extension services must be equipped for a climate era, with practical training in climate-smart practices and risk reduction. And the data systems across meteorology, irrigation, agriculture and social protection must talk to each other so that support can be triggered quickly when thresholds are crossed, instead of being assembled after losses are already locked in.

What does this mean in practice? Over the coming months, the focus should be on completing priority irrigation and drainage works with “build-back-better” standards, supporting replanting packages that include soil and drainage measures rather than seed alone, and preventing distress coping through temporary protection for the most vulnerable households. Over the next few years, the country should aim to roll out climate-smart production and advisory bundles in selected river basins, institutionalise agriculture-focused post-disaster assessments that translate into funded plans, and pilot shock-responsive safety nets and rapid-trigger insurance in cyclone-exposed districts. Over the longer term, repeated loss zones must be reoriented towards flood-compatible systems and slope-stabilising perennials, while catchment rehabilitation and natural infrastructure restoration are treated as productivity investments, not optional environmental add-ons.

None of this is abstract. The cost of inaction is paid in failed harvests, lost income, higher food prices and deeper rural debt. The opportunity is equally concrete: if Sri Lanka uses the post-Ditwah period to modernise agriculture making production more resilient, infrastructure smarter, finance faster and institutions more responsive, then Ditwah can become more than a disaster. It can become the turning point where the country decides to stop repairing vulnerability and start building resilience.

By Vimlendra Sharan,

FAO Representative for Sri Lanka and the Maldives

-

Life style22 hours ago

Life style22 hours agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoA question of national pride

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features22 hours ago

Features22 hours agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features22 hours ago

Features22 hours agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoTheatre and Anthropocentrism in the age of Climate Emergency

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoThe JRJ syndrome