Opinion

De-mystifying mediation for dispute resolution – II

(Continued from yesterday)

Reference by courts to mediation is a universally accepted phenomenon. In the recent Churchill case (November 2024), the UK Court of Appeal determined that the courts of England and Wales can lawfully stay proceedings and or order the parties to engage in non-court-based dispute resolution processes which includes mediation, provided that order does not impair the essence of the claimants right to a fair trial, is made in pursuit of a legitimate claim, and is proportionate to achieving that legitimate claim.

The mediation process is informal, structured, non-adversarial and disciplined. The Bill sets out how a mediation can be initiated in different circumstances, ie. when there is a mediation agreement and also when parties agree to mediate after a dispute arises even without a prior mediation agreement. The concept of the ‘Mediation Service Provider’ (MSP) is recognised. An MSP is an important player in the process because it is the MSP that provides administrative support. An MSP can be a single individual or an entity. The obligations of an MSP are provided for in the Bill itself to ensure that important global standards are complied with. This provision is one of those that seeks to ensure that internationally accepted standards are complied with.

Disputants must engage directly and voluntarily in good faith

and must be present at the mediation sessions. The good faith principle is important to ensure that disputants are sincerely committed to a settlement and must provide full disclosure of matters that are relevant to a sustainable solution. The process ensures party autonomy which means that the parties take all decisions regarding the settlement or the refusal to settle. The process has no focus on adjudication of legal rightsand wrongs and has a focus on assisting parties to identify and satisfy their concerns.

Legal representation is not essential but Lawyers and other professionals (Engineers, Doctors, Architects, Family Counselors, Surveyors, Actuaries) can attend the sessions to assist the disputants and advise on settlements. Lawyers do have a role in mediation and must engage as strategic partners. Globally, Lawyers are trained in mediation advocacy to equip them with the skills necessary to perform a niche role in mediations, which role is very different to the one Lawyers assume in an adversarial process.

The Mediator must be independent, impartial and have no conflict of interest. Professional Mediators are trained in the core skills and techniques that are relevant to assist parties to better understand their concerns, to communicate effectively and to identify creative solutions that satisfy their concerns. The Mediator functions as a Communicator, a Negotiator, and a Manager. These roles require specific skills and hence specialized training is of the essence as in any other profession.

Confidentiality must be maintained by all parties and by the Mediator with regard to matters discussed and submissions made during the mediation. The without prejudice rule also applies and serves to assure to the disputants the space to discuss matters freely and creatively without fear that thoughts generated and solutions suggested at the mediation sessions will be used against them as a surrender of rights or an admission of a position, in the event that any other dispute resolution process is pursued thereafter.

Where a settlement is reached, the terms and conditions are incorporated in a Settlement Agreement and signed by the parties. Such an agreement has the same sanctity as any other agreement entered into by parties and is valid in law and enforceable in a court of law. If a settlement is not reached, a certificate of non-settlement is issued to the parties. Although a decree of court is not necessary to provide validity to the agreement, if a party desires to obtain a decree based on the terms of the settlement, an application may be made to the High Court. The Bill provides of the procedure to be followed to obtain a decree and includes provisions to ensure speedy disposal of such applications. Grounds for refusal to grant a decree are included and adopt some of the UN Convention grounds. These include incapacity of a signatory, Mediator malfeasance without which the party would not have entered into the agreement, that the grant of a decree would be contrary to public policy of Sri Lanka and that the subject matter is not capable of settlement by mediation.

Why ADR and why Mediation?

Laws Delays – Globally, ADR mechanisms including mediation, have been resorted to by Governments and by disputants, due to the serious issue of laws delays. In Sri Lanka the number of cases pending in all courts in the country at the end of 2024 amounted to just over one million. It is clear that laws delays have reached phenomenal levels and that costs of litigation are overwhelming for many litigants. The cost of maintaining the administration of justice system in a country is significant and is a burden on the State. For trade, business and investment, delays in resolving business disputes detract from their corporate objectives, retard the achievement of business targets, and consume the time of executives.

Contract enforcement must improve – Sri Lanka has a weak contract enforcement record and its performance was marked as being below the South Asian average. This impacts adversely on business and is a deterrent to investors. Henceforth the World Bank will use its B-READY index to measure the business climate of economies. The indicators will provide important data that investors will look at, to make investment decisions and which businesses will examine to make better business decisions. If Sri Lanka desires to offer itself as an attractive investment destination, the dispute resolution regime must be improved.

Benefits of Mediation – The widely accepted benefits of Mediation are that it is cost effective, time efficient, has the potential to reduce the instances when a dispute leads to the termination of a business relationship, and produces savings in the administration of justice for States. These benefits are articulated in the preamble of the UN Mediation Convention and are articulated by international bodies such as WIPO, ICC, ICSID, IBA, to name but a few. It is because the practice of mediation has generated these benefits over several years of use that its popularity has grown.

Mediation is popular globally –In 2018 the United Nations adopted the Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation (the Singapore Mediation Convention) responding to a call for a uniform framework to enforce mediated agreements across borders. The need for such a framework was due to the increasing use of mediation for the resolution of cross border trade and business disputes. Sri Lanka signed the Convention in 2019 and enacted domestic legislation in 2024.International Organisations that previously offered only arbitration services such as WIPO, ICC, ICSID, IBA had adopted mediation Rules and have been providing mediation services for many years.

Mediation in domestic regimes – Many countries have institutionalised mediation in their domestic laws including for mandatory use at the pre trial stage. Some jurisdictions provide for court annexed mediation which means that mediation is integrated into the judicial system. Other jurisdictions provide for court referred mediation.

The UK’s civil justice reforms of 1999 which were inspired by Lord Woolf’s review of the civil Justice system contained a recommendation that ADR be pursued prior to litigation. Many amendments were made to the Civil Procedure Rules including as recently as 2024 to provide for courts to exercise greater powers to mandate mediation.

India enacted the Mediation Act 2023 which provides a framework for the conduct of mediations and also encourages pre-trial mediation by stating that whether any mediation agreement exists or not, the parties before filing a civil or commercial action, may voluntarily and with mutual consent take steps to settle the disputes by pre-litigation mediation. This clearly articulates a pre-trial, pro mediation bias.

Some other countries in the Asian region that have institutionalised mediation include – Hong Kong (Mediation Ordinance 2013), Singapore (Mediation Acts of 2017 and 2020), Malaysia (Mediation Act, 2012 and AIAC (Malaysia) 2018), Pakistan (CPC as amended and the ADR Act, 2027), Japan (Civil Mediation Act, 1951). Singapore in particular is a leader in the provision of mediation services.

The EU adopted the EU Mediation Directive in 2008 and many European countries have institutionalised mediation.

USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand are some countries that have a long history of the use of mediation.

The International Mediation Institute (IMI)

is a body with a global reach, dedicated to driving transparency and standards in mediation worldwide. Its vision is “Professional Mediation worldwide: promoting consensus and access to justice.”

Is Sri Lanka ready to provide mediation services?

Yes. A number of persons including Lawyers and other professionals have been trained at international Training Institutes, received accreditation and are available to provide services. Trained Mediators have already conducted mediations and the number of disputes being referred to mediation is increasing. Opportunities to obtain training and accreditation from international accreditation Institutes are offered, aided also by Institutions such as UDecide that facilitate training opportunities. The International ADR Center which is a purely private sector non-profit Company has its own Institutional Rules for Mediation and provide services and infrastructure facilities of international standards, including for virtual mediations which have already taken place. The International Chamber of Commerce (Sri Lanka) and the Sri Lanka National Arbitration Centre also have the capability to provide mediation services.

A majority of the trained group includes Lawyers. Trained Mediators continue to develop their learnings and skills and an Association of Trained Mediators is being established. Following global trends, a group of Lawyers have been trained in mediation advocacy to learn the skills to perform their niche role in the mediation process and the trainings will continue.

Is Regulation necessary?

While accreditation for Mediators and MSPs is vital to ensure that standards are maintained, the need for regulation should be addressed with care. Given that Arbitrators have no regulatory regime, the argument is often advanced as to, Why then for mediators and MSPs? Given that the Mediation Bill itself sets down standards for Mediators, MSPs, disputants and sets out the procedure, a regulation framework, if found necessary, must be designed to ensure efficiency and value addition, rather than to provide for regulation for the sake of regulation.

Conclusion

The challenge today is to provide disputants with access to meaningful dispute resolution processes that may be pursued with confidence and which, in their judgment will offer them a result that will satisfy their requirements. This issue assumes a greater degree of importance given the state of the litigation overload in the country and the resulting delays, expense and unpredictability that deny disputants the justice that they seek. It is this context that the initiative to institutionalise Mediation as a mechanism that has proved successful globally and to sustain it in its purest form, assumes relevance.

The Bill before Parliament is timely and will contribute to establishing a comprehensive eco system for the use of mediation in its purest form in Sri Lanka. In time, given the geopolitical imperatives, Sri Lanka can develop into an ADR hub that can be accessed by international partners with confidence.

by Dhara Wijayatilake,

Attorney at Law, Director and Secretary General of the International ADR Center, Sri Lanka; former Secretary to the Ministry of Justice.

Opinion

The policy of Sinhala Only and downgrading of English

In 1956 a Sri Lankan politician riding a great surge of populism, made a move that, at a stroke, disabled a functioning civil society operating in the English language medium in Sri Lanka. He had thrown the baby out with the bathwater.

It was done to huge, ecstatic public joy and applause at the time but in truth, this action had serious ramifications for the country, the effects have, no doubt, been endlessly mulled over ever since.

However, there is one effect/ aspect that cannot be easily dismissed – the use of legal English of an exact technical quality used for dispensing Jurisprudence (certainty and rational thought). These court certified decisions engendered confidence in law, investment and business not only here but most importantly, among the international business community.

Well qualified, rational men, Judges, thought rationally and impartially through all the aspects of a case in Law brought before them. They were expert in the use of this specialised English, with all its meanings and technicalities – but now, a type of concise English hardly understandable to the casual layman who may casually look through some court proceedings of yesteryear.

They made clear and precise rulings on matters of Sri Lankan Law. These were guiding principles for administrative practice. This body of case law knowledge has been built up over the years before Independence. This was in fact, something extremely valuable for business and everyday life. It brought confidence and trust – essential for conducting business.

English had been developed into a precise tool for analysing and understanding a problem, a matter, or a transaction. Words can have specific meanings, they were not, merely, the play- thing of those producing “fake news”. English words as used at that time, had meaning – they carried weight and meaning – the weight of the law!

Now many progressive countries around the world are embracing English for good economic and cultural reasons, but in complete contrast little Sri Lanka has gone into reverse!

A minority of the Sinhalese population, (the educated ones!) could immediately see at the time the problems that could arise by this move to down-grade English including its high-quality legal determinations. Unfortunately, seemingly, with the downgrading of English came a downgrading of the quality of inter- personal transactions.

A second failure was the failure to improve the “have nots” of the villagers by education. Knowledge and information can be considered a universal right. Leonard Woolf’s book “A village in the Jungle” makes use of this difference in education to prove a point. It makes infinitely good politics to reduce this education gap by education policies that rectify this important disadvantage normal people of Sri Lanka have.

But the yearning of educators to upgrade the education system as a whole, still remains a distant goal. Advanced English spoken language is encouraged individually but not at a state level. It has become an orphaned child. It is the elites that can read the standard classics such as Treasure Island or Sherlock Holmes and enjoy them.

But, perhaps now, with the country in the doldrums, more people will come to reflect on these failures of foresight and policy implementation. Isn’t the doldrums all the proof you need?

by Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

GOODBYE, DEAR SIR

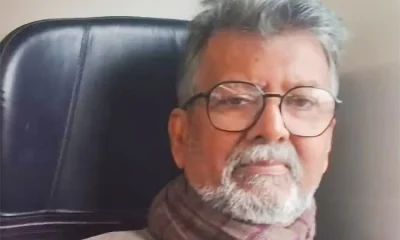

It is with deep gratitude and profound sorrow that we remember Mr. K. L. F. Wijedasa, remarkable athletics coach whose influence reached far beyond the track. He passed away on November 4, exactly six months after his 93rd birthday, having led an exemplary and disciplined life that enabled him to enjoy such a long and meaningful innings. To those he trained, he was not only a masterful coach but a mentor, a friend, a steady father figure, and an enduring source of inspiration. His wisdom, kindness, and unwavering belief in every young athlete shaped countless lives, leaving a legacy that will continue to echo in the hearts of all who were fortunate enough to be guided by him.

I was privileged to be one of the many athletes who trained under his watchful eye from the time Mr. Wijedasa began his close association with Royal College in 1974. He was largely responsible for the golden era of athletics at Royal College from 1973 to 1980. In all but one of those years, Royal swept the board at all the leading Track & Field Championships — from the Senior and Junior Tarbat Shields to the Daily News Trophy Relay Carnival. Not only did the school dominate competitions, but it also produced star-class athletes such as sprinter Royce Koelmeyer; sprint and long & triple jump champions Godfrey Fernando and Ravi Waidyalankara; high jumper and pole vaulter Cletus Dep; Olympic 400m runner Chrisantha Ferdinando; sprinters Roshan Fernando and the Indraratne twins, Asela and Athula; and record-breaking high jumper Dr. Dharshana Wijegunasinghe, to name just a few.

Royal had won the Senior & Junior Tarbats as well as the Relay Carnival in 1973 by a whisker and was looking for a top-class coach to mould an exceptionally talented group of athletes for 1974 and beyond. This was when Mr. Wijedasa entered the scene, beginning a lifelong relationship with the athletes of Royal College from 1974 to 1987. He received excellent support from the then Principal, late Mr. L. D. H. Pieris; Vice Principal, late Mr. E. C. Gunesekera; and Masters-in-Charge Mr. Dharmasena, Mr. M. D. R. Senanayake, and Mr. V. A. B. Samarakone, with whom he maintained a strong and respectful rapport throughout his tenure.

An old boy of several schools — beginning at Kandegoda Sinhala Mixed School in his hometown, moving on to Dharmasoka Vidyalaya, Ambalangoda, Moratu Vidyalaya, and finally Ananda College — he excelled in both sports and studies. He later graduated in Geography, from the University of Peradeniya. During his undergraduate days, he distinguished himself as a sprinter, establishing a new National Record in the 100 metres in 1955. Beyond academics and sports, Mr. Wijedasa also demonstrated remarkable talent in drama.

Though proudly an Anandian, he became equally a Royalist through his deep association with Royal’s athletics from the 1970s. So strong was this bond that he eventually admitted his only son, Duminda, to Royal College. The hallmark of Mr. Wijedasa was his tireless dedication and immense patience as a mentor. Endurance and power training were among his strengths —disciplines that stood many of us in good stead long after we left school.

More than champions on the track, it is the individuals we became in later life that bear true testimony to his loving guidance. Such was his simplicity and warmth that we could visit him and his beloved wife, Ransiri, without appointment. Even long after our school days, we remained in close touch. Those living overseas never failed to visit him whenever they returned to Sri Lanka. These visits were filled with fond reminiscences of our sporting days, discussions on world affairs, and joyful moments of singing old Sinhala songs that he treasured.

It was only fitting, therefore, that on his last birthday on May 4 this year, the Old Royalists’ Athletic Club (ORAC) honoured him with a biography highlighting his immense contribution to athletics at Royal. I was deeply privileged to co-author this book together with Asoka Rodrigo, another old boy of the school.

Royal, however, was not the first school he coached. After joining the tutorial staff of his alma mater following graduation, he naturally coached Ananda College before moving on to Holy Family Convent, Bambalapitiya — where he first met the “love of his life,” Ransiri, a gifted and versatile sportswoman. She was not only a national champion in athletics but also a top netballer and basketball player in the 1960s. After his long and illustrious stint at Royal College, he went on to coach at schools such as Visakha Vidyalaya and Belvoir International.

The school arena was not his only forte. Mr. Wijedasa also produced several top national athletes, including D. K. Podimahattaya, Vijitha Wijesekera, Lionel Karunasena, Ransiri Serasinghe, Kosala Sahabandu, Gregory de Silva, Sunil Gunawardena, Prasad Perera, K. G. Badra, Surangani de Silva, Nandika de Silva, Chrisantha Ferdinando, Tamara Padmini, and Anula Costa. Apart from coaching, he was an efficient administrator as Director of Physical Education at the University of Colombo and held several senior positions in national sporting bodies. He served as President of the Amateur Athletic Association of Sri Lanka in 1994 and was also a founder and later President of the Ceylonese Track & Field Club. He served with distinction as a national selector, starter, judge, and highly qualified timekeeper.

The crowning joy of his life was seeing his legacy continue through his children and grandchildren. His son, Duminda, was a prominent athlete at Royal and later a National Squash player in the 1990s. In his later years, Mr. Wijedasa took great pride in seeing his granddaughter, Tejani, become a reputed throwing champion at Bishop’s College, where she currently serves as Games Captain. Her younger brother, too, is a promising athlete.

He is survived by his beloved wife, Ransiri, with whom he shared 57 years of a happy and devoted marriage, and by their two children, Duminda and Puranya. Duminda, married to Debbie, resides in Brisbane, Australia, with their two daughters, Deandra and Tennille. Puranya, married to Ruvindu, is blessed with three children — Madhuke, Tejani, and Dharishta.

Though he has left this world, the values he instilled, the lives he shaped, and the spirit he ignited on countless tracks and fields will live on forever — etched in the hearts of generations who were privileged to call him Sir (Coach).

NIRAJ DE MEL, Athletics Captain of Royal College 1976

Deputy Chairman, Old Royalists’ Athletics Club (ORAC)

Opinion

Why Sri Lanka needs a National Budget Performance and Evaluation Office

Sri Lanka is now grappling with the aftermath of the one of the gravest natural disasters in recent memory, as Cyclone Ditwah and the associated weather system continue to bring relentless rain, flash floods, and landslides across the country.

In view of the severe disaster situation, Speaker Jagath Wickramaratne had to amend the schedule for the Committee Stage debates on Budget 2026, which was subsequently passed by Parliament. There have been various interpretations of Budget 2026 by economists, the business community, academics, and civil society. Some analyses draw on economic expertise, others reflect social understanding, while certain groups read the budget through political ideology. But with the country now trying to manage a humanitarian and economic emergency, it is clear that fragmented interpretations will not suffice. This is a moment when Sri Lanka needs a unified, responsible, and collective “national reading” of the budget—one that rises above personal or political positions and focuses on safeguarding citizens, restoring stability, and guiding the nation toward recovery.

Budget 2026 is unique for several reasons. To understand it properly, we must “read” it through the lens of Sri Lanka’s current economic realities as well as the fiscal consolidation pathway outlined under the International Monetary Fund programme. Some argue that this Budget reflects a liberal policy orientation, citing several key allocations that support this view: strong investment in human capital, an infrastructure-led growth strategy, targeted support for private enterprise and MSMEs, and an emphasis on fiscal discipline and transparency.

Anyway, it can be argued that it is still too early to categorise the 2026 budget as a fully liberal budget approach, especially when considering the structural realities that continue to shape Sri Lanka’s economy. Still some sectors in Sri Lanka restricted private-sector space, with state dominance. And also, we can witness a weak performance-based management system with no strong KPI-linked monitoring or institutional performance cells. Moreover, the country still maintains a broad subsidy orientation, where extensive welfare transfers may constrain productivity unless they shift toward targeted and time-bound mechanisms. Even though we can see improved tax administration in the recent past, there is a need to have proper tax rationalisation, requiring significant simplification to become broad-based and globally competitive. These factors collectively indicate that, despite certain reform signals, it may be premature to label Budget 2026 as fully liberal in nature.

Overall, Sri Lanka needs to have proper monitoring mechanisms for the budget. Even if it is a liberal type, development, or any type of budget, we need to see how we can have a budget monitoring system.

Establishing a National Budget Performance and Evaluation Office

Whatever the budgets presented during the last seven decades, the implementation of budget proposals can always be mostly considered as around 30-50 %. Sri Lanka needs to have proper budget monitoring mechanisms. This is not only important for the budget but also for all other activities in Sri Lanka. Most of the countries in the world have this, and we can learn many best practices from them.

Establishing a National Budget Performance and Evaluation Office is essential for strengthening Sri Lanka’s fiscal governance and ensuring that public spending delivers measurable value. Such an office would provide an independent, data-driven mechanism to track budget implementation, monitor programme outcomes, and evaluate whether ministries achieve their intended results. Drawing from global best practices—including India’s PFMS-enabled monitoring and OECD programme-based budgeting frameworks—the office would develop clear KPIs, performance scorecards, and annual evaluation reports linked to national priorities. By integrating financial data, output metrics, and policy outcomes, this institution would enable evidence-based decision-making, improve budget credibility, reduce wastage, and foster greater transparency and accountability across the public sector. Ultimately, this would help shift Sri Lanka’s budgeting process from input-focused allocations toward performance-oriented results.

There is an urgent need for a paradigm shift in Sri Lanka’s economy, where export diversification, strengthened governance, and institutional efficiency become essential pillars of reform. Establishing a National Budget Performance and Evaluation Office is a critical step that can help the country address many long-standing challenges related to governance, fiscal discipline, and evidence-based decision-making. Such an institution would create the mechanisms required for transparency, accountability, and performance-focused budgeting. Ultimately, for Sri Lanka to gain greater global recognition and move toward a more stable, credible economic future, every stakeholder must be equipped with the right knowledge, tools, and systems that support disciplined financial management and a respected national identity.

by Prof. Nalin Abeysekera ✍️

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoSri Lanka betting its tourism future on cold, hard numbers

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoJetstar to launch Australia’s only low-cost direct flights to Sri Lanka, with fares from just $315^