Features

Dangerous and meticulous work copying Sigiriya frescoes in Bell era (1896)

(Excerpted from Sigiriya Paintings by Raja de Silva, retired Commissioner of Archaeology)

RE-DISCOVERY AND DOCUMENTATION (Early Visits)

The village of Sigiriya is mentioned in the 16th century book of Sinhala verse titled Mandarampura-puvata. From then on, the site seems to have disappeared from the public record until its rediscovery in the 19th century. Major Forbes of the 78th Highlanders and two companions rode from Polonnaruva through Minneriya and Peikkulam in search of Sigiriya, and reached the site early in the morning of a day in April 1831 (Forbes 1841).

They returned to the site two years later and Forbes explored further the cavernous walled gallery on the western side of the great rock, which led towards the summit. Forbes was surprised to observe a durable plaster on the brickwork of the wall, while above the gallery, especially in places protected from the elements, the plaster was seen to be painted over in bright  colours. However, he was disappointed and puzzled in not recognizing any representations of the lion, which, according to local lore, gave the name of Sigiri, i.e., Sinhagiri to the rock.

colours. However, he was disappointed and puzzled in not recognizing any representations of the lion, which, according to local lore, gave the name of Sigiri, i.e., Sinhagiri to the rock.

The lion that eluded Forbes was tracked down by the next visitor, who remained anonymous in recording his impressions in 1851 under the title “From the notebook of a traveller” in a magazine known as Young Ceylon. This early visitor described the gallery as a long cavernous fissure, the outer edges of which were deeply grooved and a brick wall raised there, nearly to the roof. The inner surface of the “cave” was described as “covered with a coating of white and polished chunam gleaming as if it were a month old”.

Some of the plaster from the ceiling and the rock side of the gallery had fallen off, but it was noted by the visitor that “there was a profusion of paintings, chiefly of lions, which is said to have given the name of Singaghery, Sihagiri or Seegiry to the ancient site”. No other visitor had reported on these lions.

Twenty four years later, Sigiriya and the paintings were brought to public notice by TW Rhys Davids (1875), formerly of the Ceylon Civil Service, in a lecture given before the Royal Asiatic Society, London. Rhys Davids described his observation, through a telescope, of the “hollow” halfway up the western side of the rock, with its surface covered with a fine hard “chunam” plaster on which were painted figures. He mentioned that the northern (i.e., further) area of the gallery was covered with ornamental paintings (again, to be lost not long after) and thought that a large number of these may have been erased with the passage of time. By the close of the century, when the Archaeological Survey Department (ASD) commenced work at Sigiriya, these paintings had all disappeared.

TH Blakesley (1976) Public Works Department, viewed the paintings from afar in 1875, and reported for the first time on their subject, which he recognized to be female figures “repeated again and again”, showing only the upper parts of their bodies, and richly ornamented with jewellery. The figures (he said) had a Mongolian cast of features. Blakesley also examined the plaster layer adhering to the accessible parts of the main rock, and remarked on the existence of paddy husks in the ground.

Reports of the existence of paintings at Sigiriya had attracted the attention of connoisseurs of art in Sri Lanka and in England, and Sir William Gregory, the former Governor, requested Alick Murray (1891), Provincial Engineer, to attempt to reach the paintings and make reproductions of them. This proposal was sanctioned by Sir Arthur Gordon, the Governor, who gave every encouragement to the project. Murray went to Sigiriya, fired with enthusiasm for this pioneering venture, but was disappointed to discover that the local villagers would have no part of his plans for disturbing the rock chamber which, they imagined, was inhabited by demons. The populace, however, was, persuaded to clear the jungle at the base of the rock in the required direction, while Murray awaited the arrival of Tamil labourers who were urgently requested from South India.

The Tamil stone-cutters (who had no fear of Sinhala demons) bored holes in the rock face, one above the other, into which were fixed with cement, iron jumpers. As they went higher up the rock towards the cavern containing the paintings, the man of the lightest weight had to be selected to bore the holes. After a while, even this labourer found it difficult to ascend higher. He supplicated that if he were allowed three days of fasting and prayer, he might succeed in finishing the task. Murray answered his prayer in the affirmative, thinking that it might lighten the man’s weight and thereby help him to reach the pocket containing the paintings. Once this goal was reached, it was found that the rock floor was at too steep an angle to permit one to stand or even sit on it. A strong trestle or framework of sticks was made and secured to iron stanchions let into the rock floor. A platform was made and placed on the framework to enable one to lie on his back and view the paintings.

On June 18, 1889, Murray made his historic climb into the fresco pocket, and he worked for a whole week lying on his back on makeshift scaffolding to make tracings of six paintings in coloured chalk on tissue paper. The work was done, climbing up and down each day, (as he said) “from sunrise to sunset”, the only inmates of the cavern being swallows who used to “peck at him resentfully”. When his work was reaching conclusion, a few of his friends including SM Burrows, Government Agent, Matale, hazarded the climb to the pocket to visit him, and it was suggested that a memento be left behind. A bottle was obtained and in it were deposited a newspaper of the day, a few coins, and a list of names of friends who had visited him at work. Murray’s party was astonished when a Buddhist monk and a Saivite priest sought permission to enter the chamber, and they were accommodated by Murray. They prayed for the preservation of the bottle, thereby adding solemnity to the occasion of its sealing into the floor with cement – a ceremony that was accompanied by Murray and Burrows singing “God Save the Queen”.

An unfortunate result of Murray’s excellent efforts at tracing the paintings under the windiest of conditions was that, on detaching the tracing papers that had been pasted with gum on the periphery of each figure, an egg-shell thin layer of painted plaster (i.e., the intonaco) also came away revealing a white framework of the layer of ground underneath. Another deplorable result was that a few Tamil labourers had scribbled their names on the painted plaster. The copies made by Murray were stated by Bell to have been exhibited above the staircase of the Colombo Museum.

Murray described the paintings as having been done on the roof and upper sections of the sides of the chamber; that they represent 15 female figures in all, but no doubt many more had existed originally, as traces of them were to be seen. The freshness of the colours (he observed) was wonderful, curiously, green predominating. Each figure was stated to have been life-size and many were naked to the waist, the rest of the form being hidden by representations of clouds. They were arranged either singly or in sets of two, each couple representing (he said) a mistress and a maid.

Access to Fresco Pockets

In 1896, Bell made regular access to the fresco pockets possible by the construction of a vertical ladder of jungle timber from the gallery to the cemented floor that was spread on the sloping -round of the rock cavern 40′ above. The shorter and narrower pocket A was made accessible from pocket B by a floor of iron planks set on iron rods as supports let into the surface of the rock horizontally and grouted in.

The early timber ladder was replaced by an iron wire vertical ladder with safety measures of hoops of cane and wire netting around it in 1896. A spiral staircase of iron steps was constructed in 1938. Another similar staircase was recently constructed by the Central Cultural Fund (CCF) cheek-by-jowl with the earlier construction, and is used as the method of access to the fresco pocket at a point to the south of the original doorway. Visitors now use the old stairway as the exit from the pocket.

Eighty five years ago entry to the fresco pockets was restricted to those who had obtained permits from the Archaeological Commissioner. (AC).

The public has the opportunity of taking their cameras into the fresco pockets, on permits issued by the ASD, and photographing the paintings. No persons are allowed to have their photographs taken in front of the paintings, and at least two guards are stationed inside the fresco pockets as a security measure. No electronic or other flash-lights are permitted in photographing the paintings.

Documentation and Copying of the Paintings

Bell decided to photograph the pockets from a distance at the same elevation, and record the disposition of the paintings within. For this purpose a four inch hawser was let down from the summit to the ground with an iron block tied to the end. Through the block a two inch rope was passed and an improvised chair firmly tied to it, whereon the photographer took his seat. The hawser was then hauled up from the summit, 150 feet up until the chair was level with the pocket and 50 feet clear of the cliff, but due to the force of the wind that caused it to sway in the air, the photographs taken were not clear.

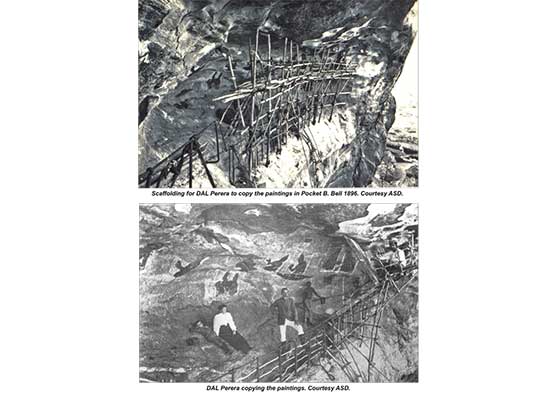

It took DAL Perera, Chief Draughtsman and Bell’s “Native Assistant”, a week to do an oil painting to scale, while perilously suspended in mid-air like the man on the flying trapeze. The painting was later photographed and lithographed to make a plate. From the top of the iron ladder the rock curved inwards for four feet or so to an upward rising floor of pocket B where it was not possible to safely stand or even sit on the smooth surface. As a safeguard at the head of the ladder and along the entire edge of both pockets B and A to the north of it and the ledge between them, iron standards three foot three inches in height, with a single top rail, were driven into the rock Bell stated: “Without such a handrail, a slip on the smooth inclined floor of the pocket would have meant instant death on the rocks fifty yards below.”

In the last week of March 1896, Perera made copies of six paintings in pocket B while being dangerously seated on the sloping floor. In the following year with additional safeguards and working platforms, Perera continued copying the remaining paintings in the two pockets. Bell reported that 13 of the paintings in pocket B could be easily reached from the floor, being painted on the rock wall and the lower part of the oblique roof of the cave, but they were not at one level. It was these paintings that Perera copied in 1896 and 1897 while being uncomfortably perched on the sloping floor of the fresco pocket, which had in 1897 been cemented towards the outer edge.

The painting at the extreme south, i.e., No. 14 and the fragments No. 15, 16, 17, were out of reach and well up on the roof of the pocket. To get at these paintings, it was necessary to construct a “cantilever” of jungle timber, firmly lashed to a stout iron cramp let into the rock floor. To the end of this projection was tied a rough “cage” of sticks, from which uncomfortable and perilous perch Perera made copies of the last and highest figures in pocket B.

It was even more difficult and dangerous to fix a hurdle platform outside the narrow and slippery ledge separating pocket B from pocket A and onwards to the end of this pocket. It took 10 days to construct this stick-shelf (massa). In addition to P iron bars supporting the woodwork, the whole braced strongly to thick iron cramped into the rock, the platform had to be further held up by a central hawser and side ropes, hauled taut round trees on the summit 300 feet up. When finished this improvised platform stood out 15 feet from the cliff.

It took Perera 19 weeks to complete copying the 22 paintings – 5 in pocket A and 17 in pocket B.

The constructional details and measurements given above are intended to serve several purposes: to enable the reader to appreciate the labour and expertise in 1896 exercised by the authorities in setting up the elaborate apparatus for Perera to copy and photograph the paintings – all for the love of preserving our ancient artwork; to appreciate the great care taken by Perera under perilous conditions to make such excellent copies of 22 paintings, now exhibited in the Colombo Museum, which Bell extolled in superlative terms:

“It is hardly going too far to assert that the copies represent the original frescoes as they may still be seen at Sigiriya, with a faithfulness almost perfect. Not a line, not a flaw or abrasion, not a shade of colour, but has been reproduced with the minutest accuracy”. (Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Ceylon Branch (1897).

The details and measurements are also intended to impress upon readers the magnitude of the feats of our craftsman in ancient times, who constructed broad, long scaffoldings rising to a height of around 400 feet using jungle timber and creepers; and to marvel that the artists painted their subject so well, during a very long period upon multi-layered plaster on the wind-blown exposed rock.

Features

Lasting solutions require consensus

Problems and solutions in plural societies like Sri Lanka’s which have deep rooted ethnic, religious and linguistic cleavages require a consciously inclusive approach. A major challenge for any government in Sri Lanka is to correctly identify the problems faced by different groups with strong identities and find solutions to them. The durability of democratic systems in divided societies depends less on electoral victories than on institutionalised inclusion, consultation, and negotiated compromise. When problems are defined only through the lens of a single political formation, even one that enjoys a large electoral mandate, such as obtained by the NPP government, the policy prescriptions derived from that diagnosis will likely overlook the experiences of communities that may remain outside the ruling party. The result could end up being resistance to those policies, uneven implementation and eventual political backlash.

A recent survey done by the National Peace Council (NPC), in Jaffna, in the North, at a focus group discussion for young people on citizen perception in the electoral process, revealed interesting developments. The results of the NPC micro survey support the findings of the national survey by Verite Research that found that government approval rating stood at 65 percent in early February 2026. A majority of the respondents in Jaffna affirm that they feel safer and more fairly treated than in the past. There is a clear improving trend to be seen in some areas, but not in all. This survey of predominantly young and educated respondents shows 78 percent saying livelihood has improved and an equal percentage feeling safe in daily life. 75 percent express satisfaction with the new government and 64 percent believe the state treats their language and culture fairly. These are not insignificant gains in a region that bore the brunt of three decades of war.

Yet the same survey reveals deep reservations that temper this optimism. Only 25 percent are satisfied with the handling of past issues. An equal percentage see no change in land and military related concerns. Most strikingly, almost 90 percent are worried about land being taken without consent for religious purposes. A significant number are uncertain whether the future will be better. These negative sentiments cannot be brushed aside as marginal. They point to unresolved structural questions relating to land rights, demilitarisation, accountability and the locus of political power. If these issues are not addressed sooner rather than later, the current stability may prove fragile. This suggests the need to build consensus with other parties to ensure long-term stability and legitimacy, and the need for partnership to address national issues.

NPP Absence

National or local level problems solving is unlikely to be successful in the longer term if it only proceeds from the thinking of one group of people even if they are the most enlightened. Problem solving requires the engagement of those from different ethno-religious, caste and political backgrounds to get a diversity of ideas and possible solutions. It does not mean getting corrupted or having to give up the good for the worse. It means testing ideas in the public sphere. Legitimacy flows not merely from winning elections but from the quality of public reasoning that precedes decision-making. The experience of successful post-conflict societies shows that long term peace and development are built through dialogue platforms where civil society organisations, political actors, business communities, and local representatives jointly define problems before negotiating policy responses.

As a civil society organisation, the National Peace Council engages in a variety of public activities that focus on awareness and relationship building across communities. Participants in those activities include community leaders, religious clergy, local level government officials and grassroots political party representatives. However, along with other civil society organisations, NPC has been finding it difficult to get the participation of members of the NPP at those events. The excuse given for the absence of ruling party members is that they are too busy as they are involved in a plenitude of activities. The question is whether the ruling party members have too much on their plate or whether it is due to a reluctance to work with others.

The general belief is that those from the ruling party need to get special permission from the party hierarchy for activities organised by groups not under their control. The reluctance of the ruling party to permit its members to join the activities of other organisations may be the concern that they will get ideas that are different from those held by the party leadership. The concern may be that these different ideas will either corrupt the ruling party members or cause dissent within the ranks of the ruling party. But lasting reform in a plural society requires precisely this exposure. If 90 percent of surveyed youth in Jaffna are worried about land issues, then engaging them, rather than shielding party representatives from uncomfortable conversations, is essential for accurate problem identification.

North Star

The Leader of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), Prof Tissa Vitarana, who passed away last week, gave the example for national level problem solving. As a government minister he took on the challenge the protracted ethnic conflict that led to three decades of war. He set his mind on the solution and engaged with all but never veered from his conviction about what the solution would be. This was the North Star to him, said his son to me at his funeral, the direction to which the Compass (Malimawa) pointed at all times. Prof Vitarana held the view that in a diverse and plural society there was a need to devolve power and share power in a structured way between the majority community and minority communities. His example illustrates that engagement does not require ideological capitulation. It requires clarity of purpose combined with openness to dialogue.

The ethnic and religious peace that prevails today owes much to the efforts of people like Prof Vitarana and other like-minded persons and groups which, for many years, engaged as underdogs with those who were more powerful. The commitment to equality of citizenship, non-racism, non-extremism and non-discrimination, upheld by the present government, comes from this foundation. But the NPC survey suggests that symbolic recognition and improved daily safety are not enough. Respondents prioritise personal safety, truth regarding missing persons, return of land, language use and reduction of military involvement. They are also asking for jobs after graduation, local economic opportunity, protection of property rights, and tangible improvements that allow them to remain in Jaffna rather than migrate.

If solutions are to be lasting they cannot be unilaterally imposed by one party on the others. Lasting solutions cannot be unilateral solutions. They must emerge from a shared diagnosis of the country’s deepest problems and from a willingness to address the negative sentiments that persist beneath the surface of cautious optimism. Only then can progress be secured against reversal and anchored in the consent of the wider polity. Engaging with the opposition can help mitigate the hyper-confrontational and divisive political culture of the past. This means that the ruling party needs to consider not only how to protect its existing members by cloistering them from those who think differently but also expand its vision and membership by convincing others to join them in problem solving at multiple levels. This requires engagement and not avoidance or withdrawal.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Unpacking public responses to educational reforms

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

Two broad reactions

The reactions to the proposed reforms can be broadly categorised into ‘pro’ and ‘anti’. I will discuss the latter first. Most of the backlash against the reforms seems to be directed at the issue of a gay dating site, accidentally being linked to the Grade 6 English module. While the importance of rigour cannot be overstated in such a process, the sheer volume of the energies concentrated on this is also indicative of how hopelessly homophobic our society is, especially its educators, including those in trade unions. These dispositions are a crucial part of the reason why educational reforms are needed in the first place. If only there was a fraction of the interest in ‘keeping up with the rest of the world’ in terms of IT, skills, and so on, in this area as well!

Then there is the opposition mounted by teachers’ trade unions and others about the process of the reforms not being very democratic, which I (and many others in higher education, as evidenced by a recent statement, available at https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/ ) fully agree with. But I earnestly hope the conversation is not usurped by those wanting to promote heteronormativity, further entrenching bigotry only education itself can save us from. With this important qualification, I, too, believe the government should open up the reform process to the public, rather than just ‘informing’ them of it.

It is unclear both as to why the process had to be behind closed doors, as well as why the government seems to be in a hurry to push the reforms through. Considering other recent developments, like the continued extension of emergency rule, tabling of the Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), and proposing a new Authority for the protection of the Central Highlands (as is famously known, Authorities directly come under the Executive, and, therefore, further strengthen the Presidency; a reasonable question would be as to why the existing apparatus cannot be strengthened for this purpose), this appears especially suspect.

Further, according to the Secretary to the MOE Nalaka Kaluwewa: “The full framework for the [education] reforms was already in place [when the Dissanayake government took office]” (https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2025/08/12/wxua-a12.html, citing The Morning, July 29). Given the ideological inclinations of the former Wickremesinghe government and the IMF negotiations taking place at the time, the continuation of education reforms, initiated in such a context with very little modification, leaves little doubt as to their intent: to facilitate the churning out of cheap labour for the global market (with very little cushioning from external shocks and reproducing global inequalities), while raising enough revenue in the process to service debt.

This process privileges STEM subjects, which are “considered to contribute to higher levels of ‘employability’ among their graduates … With their emphasis on transferable skills and demonstrable competency levels, STEM subjects provide tools that are well suited for the abstraction of labour required by capitalism, particularly at the global level where comparability across a wide array of labour markets matters more than ever before” (my own previous piece in this column on 29 October 2024). Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) subjects are deprioritised as a result. However, the wisdom of an education policy that is solely focused on responding to the global market has been questioned in this column and elsewhere, both because the global market has no reason to prioritise our needs as well as because such an orientation comes at the cost of a strategy for improving the conditions within Sri Lanka, in all sectors. This is why we need a more emancipatory vision for education geared towards building a fairer society domestically where the fruits of prosperity are enjoyed by all.

The second broad reaction to the reforms is to earnestly embrace them. The reasons behind this need to be taken seriously, although it echoes the mantra of the global market. According to one parent participating in a protest against the halting of the reform process: “The world is moving forward with new inventions and technology, but here in Sri Lanka, our children are still burdened with outdated methods. Opposition politicians send their children to international schools or abroad, while ours depend on free education. Stopping these reforms is the lowest act I’ve seen as a mother” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). While it is worth mentioning that it is not only the opposition, nor in fact only politicians, who send their children to international schools and abroad, the point holds. Updating the curriculum to reflect the changing needs of a society will invariably strengthen the case for free education. However, as mentioned before, if not combined with a vision for harnessing education’s emancipatory potential for the country, such a move would simply translate into one of integrating Sri Lanka to the world market to produce cheap labour for the colonial and neocolonial masters.

According to another parent in a similar protest: “Our children were excited about lighter schoolbags and a better future. Now they are left in despair” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). Again, a valid concern, but one that seems to be completely buying into the rhetoric of the government. As many pieces in this column have already shown, even though the structure of assessments will shift from exam-heavy to more interim forms of assessment (which is very welcome), the number of modules/subjects will actually increase, pushing a greater, not lesser, workload on students.

A file photo of a satyagraha against education reforms

What kind of education?

The ‘pro’ reactions outlined above stem from valid concerns, and, therefore, need to be taken seriously. Relatedly, we have to keep in mind that opening the process up to public engagement will not necessarily result in some of the outcomes, those particularly in the HSS academic community, would like to see, such as increasing the HSS component in the syllabus, changing weightages assigned to such subjects, reintroducing them to the basket of mandatory subjects, etc., because of the increasing traction of STEM subjects as a surer way to lock in a good future income.

Academics do have a role to play here, though: 1) actively engage with various groups of people to understand their rationales behind supporting or opposing the reforms; 2) reflect on how such preferences are constituted, and what they in turn contribute towards constituting (including the global and local patterns of accumulation and structures of oppression they perpetuate); 3) bring these reflections back into further conversations, enabling a mutually conditioning exchange; 4) collectively work out a plan for reforming education based on the above, preferably in an arrangement that directly informs policy. A reform process informed by such a dialectical exchange, and a system of education based on the results of these reflections, will have greater substantive value while also responding to the changing times.

Two important prerequisites for this kind of endeavour to succeed are that first, academics participate, irrespective of whether they publicly endorsed this government or not, and second, that the government responds with humility and accountability, without denial and shifting the blame on to individuals. While we cannot help the second, we can start with the first.

Conclusion

For a government that came into power riding the wave of ‘system change’, it is perhaps more important than for any other government that these reforms are done for the right reasons, not to mention following the right methods (of consultation and deliberation). For instance, developing soft skills or incorporating vocational education to the curriculum could be done either in a way that reproduces Sri Lanka’s marginality in the global economic order (which is ‘system preservation’), or lays the groundwork to develop a workforce first and foremost for the country, limited as this approach may be. An inextricable concern is what is denoted by ‘the country’ here: a few affluent groups, a majority ethno-religious category, or everyone living here? How we define ‘the country’ will centrally influence how education policy (among others) will be formulated, just as much as the quality of education influences how we – students, teachers, parents, policymakers, bureaucrats, ‘experts’ – think about such categories. That is precisely why more thought should go to education policymaking than perhaps any other sector.

(Hasini Lecamwasam is attached to the Department of Political Science, University of Peradeniya).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

Features

Chef’s daughter cooking up a storm…

Don Sherman was quite a popular figure in the entertainment scene but now he is better known as the Singing Chef and that’s because he turns out some yummy dishes at his restaurant, in Rajagiriya.

Don Sherman was quite a popular figure in the entertainment scene but now he is better known as the Singing Chef and that’s because he turns out some yummy dishes at his restaurant, in Rajagiriya.

However, now the spotlight is gradually focusing on his daughter Emma Shanaya who has turned out to be a very talented singer.

In fact, we have spotlighted her in The Island a couple of times and she is in the limelight, once gain.

When Emma released her debut music video, titled ‘You Made Me Feel,’ the feedback was very encouraging and at that point in time she said “I only want to keep doing bigger and greater things and ‘You Made Me Feel’ is the very first step to a long journey.”

Emma, who resides in Melbourne, Australia, is in Sri Lanka, at the moment, and has released her very first Sinhala single.

“I’m back in Sri Lanka with a brand new single and this time it’s a Sinhalese song … yes, my debut Sinhala song ‘Sanasum Mawana’ (Bloom like a Flower).

“This song is very special to me as I wrote the lyrics in English and then got it translated and re-written by my mother, and my amazing and very talented producer Thilina Boralessa. Thilina also composed the music, and mix and master of the track.”

Emma went on to say that instead of a love song, or a young romance, she wanted to give the Sri Lankan audience a debut song with some meaning and substance that will portray her, not only as an artiste, but as the person she is.

Says Emma: “‘Sanasum Mawana’ is about life, love and the essence of a woman. This song is for the special woman in your life, whether it be your mother, sister, friend, daughter or partner. I personally dedicate this song to my mother. I wouldn’t be where I am right now if it weren’t for her.”

On Friday, 30th January, ‘Sanasum Mawana’ went live on YouTube and all streaming platforms, and just before it went live, she went on to say, they had a wonderful and intimate launch event at her father’s institute/ restaurant, the ‘Don Sherman Institute’ in Rajagiriya.

It was an evening of celebration, good food and great vibes and the event was also an introduction to Emma Shanaya the person and artiste.

Emma also mentioned that she is Sri Lanka for an extended period – a “work holiday”.

“I would like to expand my creativity in Sri Lanka and see the opportunities the island has in store for me. I look forward to singing, modelling, and acting opportunities, and to work with some wonderful people.

“Thank you to everyone that is by my side, supporting me on this new and exciting journey. I can’t wait to bring you more and continue to bloom like a flower.”

-

Life style3 days ago

Life style3 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Midweek Review7 days ago

Midweek Review7 days agoA question of national pride

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka: