Features

Climate Change Karma: Who is to be blamed?

BY Amarasiri de Silva

(Emeritus Professor,

University of Peradeniya)

We Sri Lankans are facing a spate of karma in climate change, and its consequences are not due to our faults but because of those committed by developed countries. Those developed countries exploit natural resources such as fossil fuels, gases, oil, and coal, in excess. Burning fossil fuels for energy production releases carbon dioxide, methane, fluorinated gases, and nitrous oxide into the atmosphere. These major greenhouse gases (GHG) contribute to trapping heat in Earth’s atmosphere. GHG allows sunlight but traps heat radiating from the Earth’s surface. This process, though natural and necessary as it makes the climate of Earth habitable, has been exaggerated through excessive greenhouse gas emissions from human activities, particularly the combustion of fossil fuels. The heightened concentration of greenhouse gases, especially the much-emitted ones from burning fossil, relates directly to the rise in global average temperatures that result in changes in climate through increased heat waves, melting of glaciers, rising sea levels leading to flooding, and strong storms.

Approximately 15 billion tons of fossil fuels are extracted annually worldwide; this includes coal, oil, and natural gas by the developed world in general. This comes to an average of about 41 million tons per day. Oil alone accounts for around 93 million barrels per day, and there are large additional volumes of natural gas and coal. The United States is among the largest extractors of fossil fuels worldwide. It is responsible for approximately 16% of total world production from fossil fuels and is the second largest producer, next to China. Fossil fuel extraction, refining, and combustion account for approximately 73% of all GHG emissions. For 2023, US energy use from fossil fuels was estimated at 79 quadrillion BTUs. These increased use of fossil fuels led to global warming. It has been recorded that global average surface temperatures have risen by about 1.1°C (2°F) since the late 19th century, while most of this warming occurred during the past 50 years.

China and Russia are major contributors to the global production of fossil fuels. China is the largest global producer and consumer of coal, accounting for about 47% of global coal production. Another major contributor is Russia, accounting for about 17% of global natural gas and 12% of global oil production. These two countries are the major contributors in the global energy landscape, and their production level contributes much to worldwide carbon emissions.

The most recent climate summit was held in Baku, Azerbaijan, which became a rich country due to fossil fuel extraction. Comparatively speaking, Azerbaijan accounts for around six or five percent of the global generation vis-à-vis key and major producers like the US, China, and Russia. But Azerbaijan is set to expand its production of natural gas massively. Currently, Azerbaijan produces about 37 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas a year; this is scheduled to rise to 49 bcm by 2033, which means a more than 32-percent increase. During the next ten years, the total gas extraction in Azerbaijan will reach 411 bcm and significantly contribute to global greenhouse gas emissions, equivalent to about 781 million metric tons of CO₂. While these facts are actual and megalithic, the contribution of South Asian countries towards the extraction of fossil fuel is nil or not at all.

The sub-region of South Asia that contributes a small percentage to the total amount of global fuel extraction includes countries such as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. India is the central extractor in this region, followed by coal, which is considered a way to prevent energy shortages in the economic hubs of this country. The other countries of this sub-region extract a negligible share, and these countries are highly dependent on heavy imports to meet their ever-increasing energy needs. While exact percentages for the whole region’s contribution to the global extraction of fossil fuels are not available, the overall extraction of the area is minor compared to major producers like the USA, China, and Russia.

The region’s energy mix is dominated by fossil fuels and coal being an integral part of electricity generation. Moving away from fossil fuels is problematic for these economies, which face high energy demands, economic constraints, and limited funding for renewable energy development. These dynamics illustrate the global disparities in responsibility and action on climate change, as South Asia contributes very little to global fossil fuel extraction but bears enormous consequences of climate change.

Historically, developed nations, acting in concert with large extractors like China, Russia, and the United States, have been the primary contributors to greenhouse gas emissions through industrialisation, excessive fossil fuel consumption, and large-scale resource extraction. These activities have given rise to the current global warming crisis, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events, all impacting the Global South far more disproportionately than the developed world. The concept of karma in this context raises moral questions about whether this suffering is a consequence of past actions of individual countries in South Asia or a reflection of ongoing global inequalities in wealth and power.

Countries with geographical vulnerabilities, limited resources to adapt, and a minimal historical contribution to global emissions, such as Sri Lanka in South Asia, bear the brunt of these consequences. As the cases, there could be coastal flooding, stronger-than-normal monsoons, or cyclones that engender the consequences of economic losses, dislocations, or a risk to food security. While emitting negligible quantities, such countries have to bear all these financial and sociocultural costs of climatic alteration created by the carbon-based course of growth of more industrialized economies.

This inequality creates a climate justice concern. Treaties such as the Paris Accord use words like “common but differentiated responsibilities,” insinuating that countries that are more to blame for historical emissions [should] bear the brunt of mitigation and adaptation burdens. In practice, developing nations still consider many of these responsibilities to be short of satisfactory. The calls keep on coming for reparations, more financial aid, and technology transfers. And that, still, needs to go a whole lot faster”.

The “sins” of developed nations in driving climate change have made things particularly difficult for countries like Sri Lanka, calling for urgent international collaboration and accountability to address these inequities. As Naomi Klein, a prominent Canadian political and climate activist and writer says, “All of this is why any attempt to rise to the climate challenge will be fruitless unless it is understood as part of a much broader battle of worldviews, a process of rebuilding and reinventing the very idea of the collective, the communal, the commons, and the civil after so many decades of attack and neglect.” Klein’s overarching argument is that climate change isn’t purely an environmental crisis but more of a crisis in how society is organised. This calls for climate justice. As Klein puts it, the problems we solely have with our environment cannot and will not be fixed until we view them as justice issues and accept that it is time for us to rebuild. “Global capitalism has made the depletion of resources so rapid, convenient, and barrier-free that “earth-human systems” are becoming dangerously unstable in response.” According to Klein, real progress on such matters in developing countries like Sri Lanka, which faces disproportionate effects of climate change, can only be achieved by examining the underlying mindset of resource exploitation in developed countries.

Ingrained economic systems that prize profit over sustainability need reimagining in value to protect the environment and equity in resource use. For a country like Sri Lanka, issues related to climate change are multidimensional, from increased sea levels to frequent natural disasters, which would call for an integrated but transformational response. This movement needs to reposition the outlook worldwide, mainly for developed countries, de-link resources from profit-making motives like fracking, and focus on resilience, sustainability, and justice for vulnerable communities.

I found most pivotal to Klein’s argument to be, “So climate change does not need some shiny new movement that will magically succeed where others failed. Rather, as the farthest-reaching crisis created by the extractivist worldview and one that puts humanity on a firm deadline, climate change can be the grand push that will bring together all of these still-living movements. A river running from innumerable streams, collecting from their combination at last to the sea.” The passage includes a central argumentative idea- joining all the social justice movements under the key broadened factor of the struggle with climate change. She believes that the only way to address climate change and enact real difference effectively is not by having a multitude of isolated single-issue activist groups but rather by a broad yet unified association capable of fighting all the interconnected issues brought forth by climate change, such as environmental health, social and socioeconomic inequality, and systemic oppression. Klein argues that since climate change is the product of an extractive mentality, real progress can only occur through profound changes in our values and economic systems. Since all the issues concerning climate change are linked, this movement is the only practical way of fighting back, which shall change how the world looks at the world, separating resources from profit. We have to act fast as Southern countries to get the developed nations to adopt a more responsible mindset towards climate change.

We must unite together in some coalition and demand accountability and just compensation for the damages that we go through, such as the floods and cyclones, among other disasters caused mainly by irresponsible fracking, coal mining, and fossil fuel dependence on the developed nations. The United Nations should unite the Southern nations and form a strong international organisation to advocate for climate justice and just reparations. Together, we can ask for systemic changes that will benefit the well-being of our populations and ensure equitable global progress. In this respect, what is achieved by the Sri Lankan representatives attended the Baku conference is unknown.

A key passage from Patel and Moore’s -A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things- reveals that “World ecology has emerged in the past several years as a framework to think through human history within the web of life. Rather than start with a notion of human separation from the web of life, we ask: How do humans have power and violence and the work and inequality in which they are organised? Capitalism is not just part of ecology but is an ecology-a set of relationships integrating power, capital, and nature.” This quote shows the gravity of Patel and Moore’s argument because it frames capitalism as a complex and integrated system exploiting people and the environment. A “world-ecology” framing of capitalism places capitalism within the social and ecological. It illustrates that environmental and social injustices are intertwined. Such an understanding of capitalism would, therefore, mean that global environmental justice will be realised only when consideration is taken of the role of capitalism in forming these exploitative structures of power that take advantage of people and the Earth. By placing capitalism in the “web of life,” Patel and Moore argue for a unified response targeting the roots of ecological and social inequality- a more holistic approach than traditional environmentalism in and of itself, which only attacks one aspect of capitalism. This form of activism, they say, is called for in the quest for justice in times of global crisis.

Patel and Moore do not see the current system as broken but rather fundamentally flawed to the point where its removal, rather than traditional activism, is needed. They refer to the current period as the “Capitalocene” to emphasise capitalism’s leading role in driving environmental destruction, which suggests that simple reforms are insufficient to stop climate injustice. The idea of world-ecology allows us to see how the modern world’s violent and exploitative relationships are rooted in five centuries of capitalism.” To Naomi Klein, dystopia is a catastrophic state of the world created by unregulated climate change, abetted by an economic system that values profit and growth more than ecological and social well-being. Underpinning this is the global reliance on fossil fuels and extractive industries impelled by a neoliberal economic framework resistant to systemic change. She believes this accelerates environmental collapse and entrenches inequality in nations whose corporations continue their exploitation while less developed countries like Sri Lanka bear dire outcomes such as heavy floods, and extended droughts. There is nothing inevitable about Klein’s dystopia; it’s a call to action. Suppose humanity were to address the root causes of climate change and begin making systemic changes, such as transitioning to renewable energy, adopting sustainable practices, and engaging in collective action. In that case, she thinks it will be able to avoid further decline and build a just and sustainable future. (To be continued)

Features

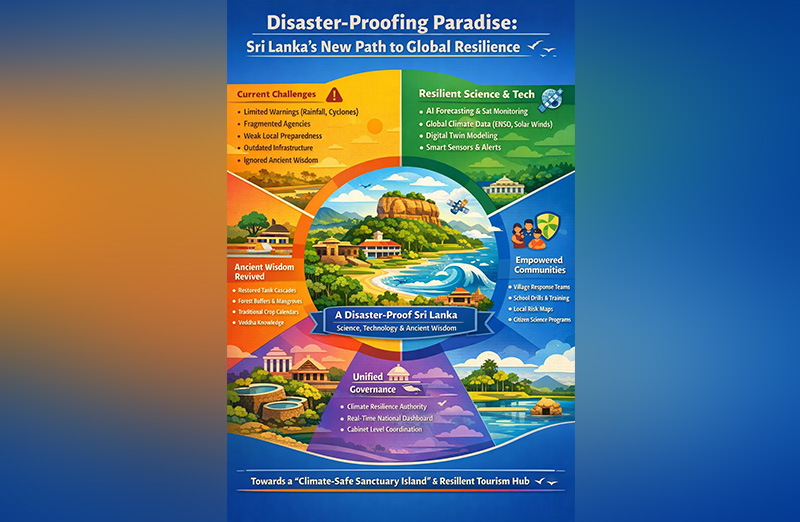

Disaster-proofing paradise: Sri Lanka’s new path to global resilience

iyadasa Advisor to the Ministry of Science & Technology and a Board of Directors of Sri Lanka Atomic Energy Regulatory Council A value chain management consultant to www.vivonta.lk

As climate shocks multiply worldwide from unseasonal droughts and flash floods to cyclones that now carry unpredictable fury Sri Lanka, long known for its lush biodiversity and heritage, stands at a crossroads. We can either remain locked in a reactive cycle of warnings and recovery, or boldly transform into the world’s first disaster-proof tropical nation — a secure haven for citizens and a trusted destination for global travelers.

The Presidential declaration to transition within one year from a limited, rainfall-and-cyclone-dependent warning system to a full-spectrum, science-enabled resilience model is not only historic — it’s urgent. This policy shift marks the beginning of a new era: one where nature, technology, ancient wisdom, and community preparedness work in harmony to protect every Sri Lankan village and every visiting tourist.

The Current System’s Fatal Gaps

Today, Sri Lanka’s disaster management system is dangerously underpowered for the accelerating climate era. Our primary reliance is on monsoon rainfall tracking and cyclone alerts — helpful, but inadequate in the face of multi-hazard threats such as flash floods, landslides, droughts, lightning storms, and urban inundation.

Institutions are fragmented; responsibilities crisscross between agencies, often with unclear mandates and slow decision cycles. Community-level preparedness is minimal — nearly half of households lack basic knowledge on what to do when a disaster strikes. Infrastructure in key regions is outdated, with urban drains, tank sluices, and bunds built for rainfall patterns of the 1960s, not today’s intense cloudbursts or sea-level rise.

Critically, Sri Lanka is not yet integrated with global planetary systems — solar winds, El Niño cycles, Indian Ocean Dipole shifts — despite clear evidence that these invisible climate forces shape our rainfall, storm intensity, and drought rhythms. Worse, we have lost touch with our ancestral systems of environmental management — from tank cascades to forest sanctuaries — that sustained this island for over two millennia.

This system, in short, is outdated, siloed, and reactive. And it must change.

A New Vision for Disaster-Proof Sri Lanka

Under the new policy shift, Sri Lanka will adopt a complete resilience architecture that transforms climate disaster prevention into a national development strategy. This system rests on five interlinked pillars:

Science and Predictive Intelligence

We will move beyond surface-level forecasting. A new national climate intelligence platform will integrate:

AI-driven pattern recognition of rainfall and flood events

Global data from solar activity, ocean oscillations (ENSO, MJO, IOD)

High-resolution digital twins of floodplains and cities

Real-time satellite feeds on cyclone trajectory and ocean heat

The adverse impacts of global warming—such as sea-level rise, the proliferation of pests and diseases affecting human health and food production, and the change of functionality of chlorophyll—must be systematically captured, rigorously analysed, and addressed through proactive, advance decision-making.

This fusion of local and global data will allow days to weeks of anticipatory action, rather than hours of late alerts.

Advanced Technology and Early Warning Infrastructure

Cell-broadcast alerts in all three national languages, expanded weather radar, flood-sensing drones, and tsunami-resilient siren networks will be deployed. Community-level sensors in key river basins and tanks will monitor and report in real-time. Infrastructure projects will now embed climate-risk metrics — from cyclone-proof buildings to sea-level-ready roads.

Governance Overhaul

A new centralised authority — Sri Lanka Climate & Earth Systems Resilience Authority — will consolidate environmental, meteorological, Geological, hydrological, and disaster functions. It will report directly to the Cabinet with a real-time national dashboard. District Disaster Units will be upgraded with GN-level digital coordination. Climate literacy will be declared a national priority.

People Power and Community Preparedness

We will train 25,000 village-level disaster wardens and first responders. Schools will run annual drills for floods, cyclones, tsunamis and landslides. Every community will map its local hazard zones and co-create its own resilience plan. A national climate citizenship programme will reward youth and civil organisations contributing to early warning systems, reforestation (riverbank, slopy land and catchment areas) , or tech solutions.

Reviving Ancient Ecological Wisdom

Sri Lanka’s ancestors engineered tank cascades that regulated floods, stored water, and cooled microclimates. Forest belts protected valleys; sacred groves were biodiversity reservoirs. This policy revives those systems:

Restoring 10,000 hectares of tank ecosystems

Conserving coastal mangroves and reintroducing stone spillways

Integrating traditional seasonal calendars with AI forecasts

Recognising Vedda knowledge of climate shifts as part of national risk strategy

Our past and future must align, or both will be lost.

A Global Destination for Resilient Tourism

Climate-conscious travelers increasingly seek safe, secure, and sustainable destinations. Under this policy, Sri Lanka will position itself as the world’s first “climate-safe sanctuary island” — a place where:

Resorts are cyclone- and tsunami-resilient

Tourists receive live hazard updates via mobile apps

World Heritage Sites are protected by environmental buffers

Visitors can witness tank restoration, ancient climate engineering, and modern AI in action

Sri Lanka will invite scientists, startups, and resilience investors to join our innovation ecosystem — building eco-tourism that’s disaster-proof by design.

Resilience as a National Identity

This shift is not just about floods or cyclones. It is about redefining our identity. To be Sri Lankan must mean to live in harmony with nature and to be ready for its changes. Our ancestors did it. The science now supports it. The time has come.

Let us turn Sri Lanka into the world’s first climate-resilient heritage island — where ancient wisdom meets cutting-edge science, and every citizen stands protected under one shield: a disaster-proof nation.

Features

The minstrel monk and Rafiki the old mandrill in The Lion King – I

Why is national identity so important for a people? AI provides us with an answer worth understanding critically (Caveat: Even AI wisdom should be subjected to the Buddha’s advice to the young Kalamas):

‘A strong sense of identity is crucial for a people as it fosters belonging, builds self-worth, guides behaviour, and provides resilience, allowing individuals to feel connected, make meaningful choices aligned with their values, and maintain mental well-being even amidst societal changes or challenges, acting as a foundation for individual and collective strength. It defines “who we are” culturally and personally, driving shared narratives, pride, political action, and healthier relationships by grounding people in common values, traditions, and a sense of purpose.’

Ethnic Sinhalese who form about 75% of the Sri Lankan population have such a unique identity secured by the binding medium of their Buddhist faith. It is significant that 93% of them still remain Buddhist (according to 2024 statistics/wikipedia), professing Theravada Buddhism, after four and a half centuries of coercive Christianising European occupation that ended in 1948. The Sinhalese are a unique ancient island people with a 2500 year long recorded history, their own language and country, and their deeply evolved Buddhist cultural identity.

Buddhism can be defined, rather paradoxically, as a non-religious religion, an eminently practical ethical-philosophy based on mind cultivation, wisdom and universal compassion. It is an ethico-spiritual value system that prioritises human reason and unaided (i.e., unassisted by any divine or supernatural intervention) escape from suffering through self-realisation. Sri Lanka’s benignly dominant Buddhist socio-cultural background naturally allows unrestricted freedom of religion, belief or non-belief for all its citizens, and makes the country a safe spiritual haven for them. The island’s Buddha Sasana (Dispensation of the Buddha) is the inalienable civilisational treasure that our ancestors of two and a half millennia have bequeathed to us. It is this enduring basis of our identity as a nation which bestows on us the personal and societal benefits of inestimable value mentioned in the AI summary given at the beginning of this essay.

It was this inherent national identity that the Sri Lankan contestant at the 72nd Miss World 2025 pageant held in Hyderabad, India, in May last year, Anudi Gunasekera, proudly showcased before the world, during her initial self-introduction. She started off with a verse from the Dhammapada (a Pali Buddhist text), which she explained as meaning “Refrain from all evil and cultivate good”. She declared, “And I believe that’s my purpose in life”. Anudi also mentioned that Sri Lanka had gone through a lot “from conflicts to natural disasters, pandemics, economic crises….”, adding, “and yet, my people remain hopeful, strong, and resilient….”.

“Ayubowan! I am Anudi Gunasekera from Sri Lanka. It is with immense pride that I represent my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka.

“I come from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka’s first capital, and UNESCO World Heritage site, with its history and its legacy of sacred monuments and stupas…….”.

The “inspiring words” that Anudi quoted are from the Dhammapada (Verse 183), which runs, in English translation: “To avoid all evil/To cultivate good/and to cleanse one’s mind -/this is the teaching of the Buddhas”. That verse is so significant because it defines the basic ‘teaching of the Buddhas’ (i.e., Buddha Sasana; this is how Walpole Rahula Thera defines Buddha Sasana in his celebrated introduction to Buddhism ‘What the Buddha Taught’ first published in1959).

Twenty-five year old Anudi Gunasekera is an alumna of the University of Kelaniya, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in International Studies. She is planning to do a Master’s in the same field. Her ambition is to join the foreign service in Sri Lanka. Gen Z’er Anudi is already actively engaged in social service. The Saheli Foundation is her own initiative launched to address period poverty (i.e., lack of access to proper sanitation facilities, hygiene and health education, etc.) especially among women and post-puberty girls of low-income classes in rural and urban Sri Lanka.

Young Anudi is primarily inspired by her patriotic devotion to ‘my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka’. In post-independence Sri Lanka, thousands of young men and women of her age have constantly dedicated themselves, oftentimes making the supreme sacrifice, motivated by a sense of national identity, by the thought ‘This is our beloved Motherland, these are our beloved people’.

The rescue and recovery of Sri Lanka from the evil aftermath of a decade of subversive ‘Aragalaya’ mayhem is waiting to be achieved, in every sphere of national engagement, including, for example, economics, communications, culture and politics, by the enlightened Anudi Gunasekeras and their male counterparts of the Gen Z, but not by the demented old stragglers lingering in the political arena listening to the unnerving rattle of “Time’s winged chariot hurrying near”, nor by the baila blaring monks at propaganda rallies.

Politically active monks (Buddhist bhikkhus) are only a handful out of the Maha Sangha (the general body of Buddhist bhikkhus) in Sri Lanka, who numbered just over 42,000 in 2024. The vast majority of monks spend their time quietly attending to their monastic duties. Buddhism upholds social and emotional virtues such as universal compassion, empathy, tolerance and forgiveness that protect a society from the evils of tribalism, religious bigotry and death-dealing religious piety.

Not all monks who express or promote political opinions should be censured. I choose to condemn only those few monks who abuse the yellow robe as a shield in their narrow partisan politics. I cannot bring myself to disapprove of the many socially active monks, who are articulating the genuine problems that the Buddha Sasana is facing today. The two bhikkhus who are the most despised monks in the commercial media these days are Galaboda-aththe Gnanasara and Ampitiye Sumanaratana Theras. They have a problem with their mood swings. They have long been whistleblowers trying to raise awareness respectively, about spreading religious fundamentalism, especially, violent Islamic Jihadism, in the country and about the vandalising of the Buddhist archaeological heritage sites of the north and east provinces. The two middle-aged monks (Gnanasara and Sumanaratana) belong to this respectable category. Though they are relentlessly attacked in the social media or hardly given any positive coverage of the service they are doing, they do nothing more than try to persuade the rulers to take appropriate action to resolve those problems while not trespassing on the rights of people of other faiths.

These monks have to rely on lay political leaders to do the needful, without themselves taking part in sectarian politics in the manner of ordinary members of the secular society. Their generally demonised social image is due, in my opinion, to three main reasons among others: 1) spreading misinformation and disinformation about them by those who do not like what they are saying and doing, 2) their own lack of verbal restraint, and 3) their being virtually abandoned to the wolves by the temporal and spiritual authorities.

(To be continued)

By Rohana R. Wasala ✍️

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result of this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoEnvironmentalists warn Sri Lanka’s ecological safeguards are failing

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoDigambaram draws a broad brush canvas of SL’s existing political situation