Opinion

1972: Another in a history of missed opportunities

1972 Construction in Retrospect – II

By Dr. Jayampathy Wickramaratne,

President’s Counsel

In the two earlier parts of this article, the writer dealt with the Constituent Assembly process that led to the First Republican Constitution and how the Constitution led to constitutionalising majoritarianism in multi-cultural Sri Lanka. In a country with a history of missed opportunities, 1972 was another.

Fundamental rights

A noteworthy feature of the 1972 Constitution is the recognition of fundamental rights. Principles of State Policy contained in another chapter were to guide the making of laws and the governance of Sri Lanka. But these Principles did not confer legal rights and were not enforceable in a court of law.

The fundamental rights guaranteed by the 1972 Constitution, however, were mainly civil and political rights: equality and equal protection, freedom from arbitrary deprivation of life, liberty and security of person, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom to enjoy and promote one’s culture, freedoms of assembly, association, speech and expression, movement and residence and freedom from discrimination in appointments in the public sector. But all these rights were subject to such restrictions as the law may prescribe in the interests of national unity and integrity, national security, national economy, public safety, public order, the protection of public health or morals or the protection of rights and freedoms of others or giving effect to the Principles of State Policy.

Thus, even the freedom from arbitrary deprivation of life and the freedom of thought, conscience and religion could be restricted. While Principles of State Policy did not confer legal rights, fundamental rights could be restricted to give effect to such principles. In several cases, the Constitutional Court held that impugned provisions of Bills that were prima facie inconsistent with fundamental rights were nevertheless for the purposes of giving effect to Principles of State Policy. It is hard to see the rationale for permitting fundamental rights, which bind all organs of government, to be restricted in the interests of Principles of State Policy which are only for guidance in law-making and governance and are not enforceable.

Much has been said about the new constitution not having a provision equivalent to section 29 (2) of the Soulbury Constitution. While the fundamental right to equality and equal protection was a safeguard against discrimination, it was subject to wide restrictions, unlike section 29 (2), which was absolute. Also, section 29 (2) was in the nature of a group right. Although it was not as effective as it was expected to be, as was demonstrated by the failure to invoke it to prevent the disenfranchisement of hundreds of thousands of Hill-Country Tamils, numerically smaller ethnic and religious groups nevertheless felt comfortable that it existed, at least on paper. They saw its omission from the 1972 Constitution as a move towards majoritarianism, especially in the context that Sri Lanka was declared a unitary state, Buddhism given the foremost place, and Sinhala declared to be the only official language.

With the ‘Republic pledged to realise the objectives of a socialist democracy’, the non-inclusion of second-generation human rights based on the principles of social justice and public obligation is puzzling. Important examples of such rights that could have been included are the right to just and favourable conditions of work, equal work for equal pay, right to rest and leisure as an employee, right to free elementary education, right to food, clothing, housing, medical care and necessary social services and right to special care and assistance for mothers and children.

Section 18 (3) of the 1972 Constitution provided that all existing laws shall operate notwithstanding any inconsistency with fundamental rights. This was in sharp contrast to the Constitution of India, which provides in Article 13 (1) that all laws in force before the commencement of the Constitution, in so far as they are inconsistent with fundamental rights, shall, to the extent of such inconsistency, be void. The 1972 Constitution did not provide for a special jurisdiction of a court for the enforcement of fundamental rights against the executive arm of the State. Theoretically, fundamental rights could have been enforced through writs in public law as well as through actions for damages, declaratory actions and injunctions in civil courts. There is only one known fundamental rights case under the 1972 Constitution, Gunaratne v People’s Bank, a declaratory action arising out of the famous bank strike of the 1970s.

Constitutionality of legislation

A significant feature of the 1972 Constitution was that, unlike under the Independence Constitution, a law could not be challenged for constitutionality. Post-enactment judicial review of legislation was thus taken away. Chapter X provided for pre-enactment judicial review. A Bill could be challenged in the Constitutional Court within a week of it being placed on the agenda of the National State Assembly (NSA).

A Bill which is, in the view of the Cabinet of Ministers, urgent in the national interest shall be referred to the Constitutional Court which shall communicate its advice to the Speaker as expeditiously as possible and in any case within twenty-four hours of the assembling of the Court.

An argument against post-enactment judicial review is that there should be certainty as regards the constitutionality of legislation. However, no serious problems have arisen in jurisdictions where post-enactment judicial review is permitted. To mitigate hardships that may be caused by legal provisions being struck down years later, the Indian Supreme Court has used the tool of ‘prospective over-ruling,’ limiting the retrospective effect of a declaration of invalidity in appropriate cases. Section 172 of the South African Constitution expressly permits such limitation.

Post-enactment judicial review is an essential tool to prevent infringement of constitutional provisions by legislative action. The effect of most legislative provisions is felt only when they are being enforced. Another argument in favour of post-enactment judicial review is that the people are able to get the benefit of the latest judicial interpretation of a constitutional provision. There have been many instances of obviously unconstitutional provisions going unchallenged. Provisions relating to urgent Bills have been abused by successive administrations. An urgent Bill is referred directly to the Supreme Court by the President even without a Gazette notification. Such a Bill is not tabled in Parliament before such reference and even Members of Parliament would not know the contents of such a Bill.

Judiciary

Under the Independence Constitution, the Chief Justice, the Judges of the Supreme Court and Commissioners of Assize were appointed by the Head of State, on the advice of the Prime Minister. The 1972 Constitution made no change in that regard.

In relation to other judicial officers, however, the provisions of the new constitution were very unsatisfactory.

Since 1946, the appointment, transfer, dismissal and disciplinary control of judicial officers had been vested in a Judicial Service Commission consisting of the Chief Justice, a Judge of the Supreme Court and another person who is or has been a Judge of the Supreme Court.

The 1972 Constitution provided for a five-member Judicial Services Advisory Board (JSAB) and a three-member Judicial Services Disciplinary Board (JSDB), both headed by the Chief Justice. A list of persons recommended for appointment as judicial officers and state officers exercising judicial functions would be forwarded by the JSAB to the Cabinet of Ministers, which was the appointing authority. The Cabinet reserved for itself the right to appoint a person not recommended by the JSAB, subject to the proviso that the full list of JSAB-recommended names and the reasons for non-acceptance of anyone so recommended were tabled in the NSA. Dismissal and disciplinary control were exercised by the JSDB, which was required to forward a report to the Cabinet through the Minister of Justice and a copy transmitted to the Speaker. A judicial officer could also be removed for misconduct by the President on an address by the NSA. J.A.L. Cooray considered the changes effected by the 1972 Constitution to be hardly compatible with the independence of the judicial function. (Constitutional and Administrative Law of Sri Lanka, 2nd edn, 69).

Public service

Under the Independence Constitution, the Permanent Secretary of each ministry was subject to the general direction and control of the Minister in exercising supervision over the departments coming under the ministry. The 1972 Constitution made no change to this position except to include institutions, such as corporations, within the ambit of the relevant provision.

Before 1972, the appointment, transfer, dismissal and disciplinary control of public officers were vested in a Public Service Commission appointed by the Governor-General. This position was changed, and the powers were taken over by the Cabinet of Ministers. Appointments were made after receiving recommendations from a State Services Advisory Board. The power of appointment could be delegated to the Minister concerned or by the Minister, in turn, to any state officer. The power of disciplinary control and dismissal was exercised after receiving a recommendation from the State Services Disciplinary Board.

The UF no doubt considered the bureaucracy to be obstructionist and wished the public service to be available to the government to accelerate socio-economic development. This is understandable. As Radhika Coomaraswamy has argued in Sri Lanka, The Crisis of the Anglo-American Constitutional Traditions in a Developing Society, the framers of the 1972 Constitution considered the checks and balances contained in the 1947 Constitution appearing to obstruct decision-making, perpetuating a status quo of privilege and domination. But rather than including appropriate constitutional provisions to ensure that political decisions were carried out by the bureaucracy, the entire public service was placed under the control of the political executive, eroding the independence that it enjoyed.

Legality and legitimacy of the Constitution

1972 was undoubtedly a legal revolution. According to L. J. M. Cooray, the question of the legality of the process followed does not arise. ‘One might just as well ask: Was the American War of Independence legal? The Constituent Assembly of Sri Lanka was part of a revolution, which aimed at overthrowing the existing constitution.’ As to the ‘legality’ of the new Constitution, Cooray stated: ‘It could be answered by posing the question: Does the stigma of illegality apply to the United States Constitution or to the Bill of Rights and the Acts of Settlement which followed the 1699 Revolution [of Britain]?’ A constitution becomes legal in the course of time if it is accepted by the people, the courts and the administration. This requirement was fulfilled in respect of the 1972 Constitution, Cooray opines. Constitutional Government in Sri Lanka, 1796-1977 (Lake House 1984) 246-247.

Legality apart, did the 1972 Constitution have the necessary legitimacy? With all political parties agreeing on the Constituent Assembly process, it was a unique opportunity to adopt a constitution that had the support of the people at large. But, instead, the United Front imposed upon the country a constitution of its choice.

Rather than impose its will on the Constituent Assembly, the UF should have accommodated the views of the various parties that answered its call to take the Constituent Assembly route. Such accommodation would have given greater legitimacy to the 1972 Constitution. That ‘legitimacy deficit’ of the 1972 Constitution no doubt helped J. R. Jayewardene, who succeeded the liberal-minded Dudley Senanayake as the leader of the UNP, to impose his own will in turn in the form of the 1978 Constitution with which the country is still straddled.

Concluding remarks

While the complete break from the British Crown, retention of the parliamentary form of government, the introduction of a fundamental rights chapter and declaration of principles of state policy were undoubtedly laudable, the 1972 Constitution also paved the way for majoritarianism and undermining of the concepts of the rule of law and the supremacy of the constitution.

1972 was also a historic opportunity to accommodate the diversity and pluralism of the people of Sri Lanka in state power and resolve the language question, an opportunity that tragically was missed. If the United Front had met the Federal Party halfway, the history of this country might have been significantly different.

Opinion

What is Jathika Chinthanaya?

A response to the ‘Anatomy of a movement: Jathika Chinthanaya’

by Dr. Sumedha S. Amarasekara

This article is a response to the question- ‘If the failure of the left was what portended Jathika Chinthanaya, what would the sterility and decay of Jathika Chinthanaya portend?’ asked by Uditha Devapriya (UD) at the end of his article: ‘Anatomy of a movement: Jathika Chinthanaya’ (The Island 15.03.2024).

In his article, UD analyses the reasons for the failure of the Left and the fallout from it. Though he is unable to specifically tie in the ‘demise of the Left’ with the ‘relevance of Jathika Chinthanaya (JC), he maintains this to be the case, more or less on the lines that nature abhors a vacuum. Despite the title, UD does not seem to discuss the anatomy of JC, and in the absence of this, it is difficult to ascertain what UD means by ‘the JC of today is no longer the JC of yesterday’. UD instinctively sees a connection between the introduction of an open economy and the aftermath that followed, and the relevance of JC. However, UD does not seem to have been able to corelate these separate concepts meaningfully, especially in the absence of a meaningful ‘definition’ of JC.

In order to answer UD’s question, one must understand the concept of JC and then look at the Left movement in this country from that perspective, it is only then that a sensible answer can be arrived at.

JC can be best described as an ideology based on a ‘civilisational consciousness’ that we have acquired over the last two and a half thousand years. According to Anagarika Dharmapala people of this country guided by this civilisational consciousness lived ‘a contended life’. Each family had a plot of land and the forest and the grasslands were open to the public for their use. The people followed the Sangha who lived a collective life. Collectivism, and not individualism, was the aim of their existence.

Our kings who ruled our country were not tyrants or despots (in a general sense, though a few of them may have been). They were guided by an ethical code – Dasa Raja Dharma, the political /economic system that had evolved over centuries guided by a civilisational consciousness; the Buddhist ‘way of living’ that we had right up until the time we came under the dominion of the British in 1815. What is critical to grasp is that even throughout the rule of the British this ‘civilisational consciousness’ remained intact throughout the villages of this country. It is this civilisational consciousness that was flourishing in the village life that is depicted in the novels by Martin Wickremasinghe (MW) and Gunadasa Amarasekera (GA). In fact, one could argue that MW is the one who started the dialogue of JC, albeit at a subconscious level.

What happened between 1815 and our Independence in 1948, changing the destiny of our country (any many other countries) was the Industrial Revolution. To appreciate the recent (during the last 200 years) economic/political changes in the world, it is pertinent to understand that despite a myriad of scientific advances and break throughs, right up until the industrial revolution there were no real changes in the day to day living.

For example, Julius Cesare arrived in Alexandria, Egypt in 48 BC riding in a ‘horse driven vehicle’ and 2000 years later Abraham Lincoln came to the White house in 1860 still in a ‘horse driven vehicle’. The industrial revolution changed all of this in an unprecedented manner and speed. The industrial revolution-starting in the 19th century- leading to a capitalistic society swept across the world and its propagation happened in this country according to the wishes of our colonial masters, the British- their ideology, expectations and beliefs.

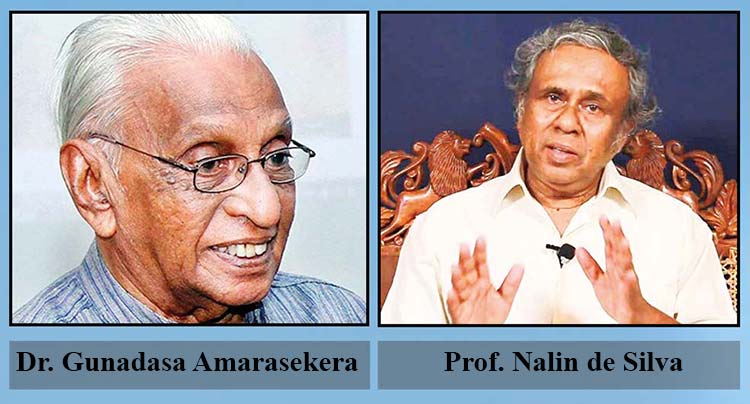

The traditional Left movement in Sri Lanka coincided with the development of the Left movements in the rest of the world- which were an alternative response to the ‘capitalistic society’ which followed the industrial revolution and the increasing ownership of private wealth. Central to these movements was the ideology expounded by Karl Marx (1818- 1883) who saw a socialist state as the next stage in the economic development where workers would own the production process (and benefits) which would lead to the eventual abolition of private property. It was this anti-capitalistic sentiment in the Left movement which resonated in both Gunadasa Amarasekera (GA) and Prof. Nalin de Silva (NdS), which is the explanation as to why both of them were sympathetic towards a Left cause.

In 1948 when we were granted independence; the United National Party (UNP) which came into power, was the de-facto ‘British party’ carrying out the economic policies for a capitalistic society with the Left political parties lined up against this. It was SWRD Bandaranaike who made the first conscious step away from this capitalistic model forming the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) in search of our own model. If Anagarika Dharmapala’s movement is considered as a national awaking of the JC, the SLFP could be considered as the beginning of a political party representing the JC.

The 1970 ‘s government under Mrs. Srimavo Bandaranaike (United Front coalition with the Left movement) was a further step away from the capitalistic direction. Despite the criticisms levelled at her government, it was the first and last time that we, as a nation achieved true economic independence under the guidance of Dr. N.M. Perera as the Minister of Finance and probably had the best foreign policy we ever had-the non-aligned policy.

In 1977, under the auspices of JR Jayewardene, our country embraced an open economic policy in a diametrically opposite path, to what had been taken up to that time. The economic path was Right centred to such an extent that the traditional Left movements became obsolete. As UD states in his article it was the open economic policies of the UNP government that paved the way for the terrorist movements in the South by the JVP and the North by the LTTE. It was a country plunging into disarray that triggered the buried ‘civilizational consciousness ‘of GA in search of our JC.

This search preceded the events in 1977. The splintering of the coalition in 1975, changed the then existing political climate and it looked as if we were leaning again towards a capitalistic path- if not lost our way. It was this feeling of impending gloom and doom that pushed GA to write ‘Abuddassa yugayak’ in 1976. This was the start of his journey towards JC.

‘Anagarika Dharmapala Marxwadida’?

which came out in 1980 embraces the ideological dialogue that GA has with the Left movement/Marxism and JC. This book is probably the most significant political analysis /review that has been done with regard to the role played by Anagarika Dharmapala and provides the deeper understanding to the political movement initiated by SWRD Bandaranaike. ‘Ganaduru mediyama dakinemi arunalu’ published 10 years after the ‘1977 – dharmishta society’ signifies the completion of GA’s study of JC. It was during this time that NdS also seemed to have moved away from his Left leanings.

At that time GA saw the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) as an umbrella group that consisted of the educated youth of this country who were unhappy with the current politics of this country. In Ganaduru mediyama dakinemi arunalu GA discusses the ideological clashes between JC and the traditional Left/ Marxist movement in great detail and as to why they failed in this country. Ganaduru mediyama dakinemi arunalu was in fact, an invitation for this group to embrace their heritage of JC and start a new path. It is probably the concept of JC that influenced politicians such as Wimal Weerawansa who were originally with the JVP to lean away from the Left /Marxist views towards nationalism.

The mid to late 1980’s can be described as a time where there was a huge debate raging throughout the country on civilisation and civilisational consciousness. This was partly due to the opposition by the Tamil separatists (militant and otherwise) and foreign powers who were out to divide this country and the NGOs that funded them. They opposed JC on two fronts, working towards this common goal of a divided Sri Lanka. One front argued that we were all part of humanity and that in reality there was no such thing as an ethnic/national identity!

The other front took the pendulum to the other end and portrayed JC as based on the ethnic consciousness of the Sinhala people and that it is a ‘Sinhala Jathika Chinthanaya’ – an ethnic nationalism based on an ethnic consciousness. GA pointed out the inherent contradiction in the term ethnic nationalism and maintained that ethnic consciousness based on culture cannot take the place of civilisational consciousness based on the harmonious co-existence of different ‘ethnic consciousnesses’ and cultures. This is what we had prior to the advent of the foreigner. There were no clashes among the ethnic groups – no fighting among them. The fights were with the invaders.

GA and NdS had to fight hard against this misconception promoted by the NGOs. It was during this period, as a medical student, that I had the privilege of being exposed to the brilliant oratory of Prof. NdS, who was then at the Department of Mathematics of the University of Colombo. Being born in 1993, UD as well as almost all of our younger generation, unfortunately would have missed these brilliant arguments given in the style of Nagasena Wasthuwa.

The issue of a national identity had an enormous impact on the country and especially the army that was fighting the war. True the army was fighting against the LTTE, but what were they fighting for? One fights for one’s family or one’s country: and here was a situation where the people as well as the world outside were made to believe that we fighting the Tamils and this was an ethnic war.

GA, NdS as well as many other national movements worked tirelessly during this period to counteract this vicious propaganda and create a sense of nationalism. It was especially in this context that the Left movements proved to be impotent. The Left movements identified only with class. They had no inherent national identity. How does a movement that does not identify with the concept of a nation support a national cause? JC was the ideology that provided the answer to this question.

The JVP movement despite being a ‘homegrown movement’ did not appreciate this fact either.

The founders of JC were able to get their message across to the people with the backing of such movements like the Patriotic National Movement and the Manel Mal movement. It was this JC movement that gave the impetus for Mahinda Rajapakse to finally win the war against the LTTE in 2009. It is the same sentiment that gave such an enormous victory to Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2019. The focus of the manifesto ‘saubagyaye dekma’ was ‘santhosayen inna pawulak’ – a happy family. The concept comes from Buddhism where happiness is seen as the ultimate wealth – ‘Santhutti Paramang Dhanang’. It is a concept of wealth that excludes money /ownership.

So, in response to UD’s article it can be seen that there is no JC of yesterday that is different to the JC of today. It is the same civilizational consciousness that comes through. Certainly, it can evolve over time. But time in this case needs to be measured relative to the civilization, in centuries, if not in millennia. As a civilizational consciousness, JC is not a movement- political or otherwise. It exists in us whether we like it or not. GA showed it and defined it for us, so that we could now consciously recognize it, acknowledge it and embrace it. The failure of the Left was its inability to recognize/comprehend JC -not that the failure of the Left portended JC.

And to finally answer the question raised by UD at the end of his article – what would the sterility and decay of Jathika Chinthanaya portend? In other words what would the sterility and decay of a civilizational consciousness portend? It will portend the end of a civilization. This is how civilizations get fossilized and disappear. And how nations get swept of the earth. In this case it portends the end of our nation. As GA would say, when he is in a pessimistic mood – ‘Maka ma dakinne may Jathiye, Rate awasanya widhiyatai’

Will it happen to us, to Sri Lanka? Have we reached the end?

Opinion

Massacre of innocents and hypocrisy of West

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

I, too, have been watching, like many millions with a conscience around the world, with a sense of helplessness, hopelessness and frustration, the indiscriminate massacre of thousands of innocent civilians, including children and the sick in Gaza by Israel Defence Forces (IDF) with the help of the West. I find it very difficult to comprehend what is worse: the persecution of a hapless group of innocents by another group which faced persecution in the past or the excuses given by leaders of the West who seem to be turning a blind eye, interrupted at times by vain gestures to indicate their disapproval! Excuses given by some of them reminds one of the well-known Sinhala saying Kanna hitunama Kabaragoyath Thlagoya venavalu which translates roughly as “When you want to eat, even a Water Monitor becomes a Land Monitor”

True, it all started with 07 October Hamas terrorist attack on Israel killed 1,139. About 300 Israelis were taken hostage. Whilst it deserved outright condemnation and a response from Israel, what is worrying is the haphazard nature of the response with glaring excesses giving the impression that Israel is hell-bent on obliterating the Gaza strip. In this venture, it is supported by USA, which seems to work on the dictum that Israel can do no wrong! Israel’s covert, and not-so-covert, plans of illegal expansion in to Palestinian territories have been legitimised by the use of its power of veto by USA, at every UN Security Council resolution.

Things started changing somewhat after the April 1st IDF drone attack on three SVU vehicles of World Central Kitchen (WCK) which killed 7 aid workers (3 British and one each of Australian, Palestinian, Polish and US-Canadian citizens) attached to the charity WCK, based in USA and run by Jose Andres, a Spanish-American chef and restaurateur. President Biden condemned the attack but the very next day USA announced further arms shipments to Israel!

Jose Andres, in addition to setting up WCK, is a professor and the founder of the Global Food Institute at George Washington University and was awarded the National Humanities Medal at a ceremony in White House in 2016. Speaking to Reuters, Andres had stated that the seven workers were “targeted deliberately” and killed “systematically, car by car” and added that the war in Gaza is “not a war against terrorism anymore” but a “war against humanity itself.” Very strong words, indeed!

Not being able to disregard this strong reaction by a respected American, President Biden had ‘strong words’ with the PM of Israel, in a telephone conversation but left it for the IDF itself to investigate the incident! IDF issued a report admitting that mistakes were made and that 2 officers were dismissed and some others warned. In response, WCK issued a statement which stated: “We demand the creation of an independent commission to investigate the killings of our WCK colleagues. The IDF cannot credibly investigate its own failure in Gaza.

It’s not enough to simply try to avoid further humanitarian deaths, which have now approached close to 200. All civilians need to be protected, and all innocent people in Gaza need to be fed and safe. And all hostages must be released”. Worryingly, the statement ends by saying that operations remain suspended.

Perhaps, this is what Israel wants; to starve the population to death! The West has remained silent, unmoved by the death over 30,000 Palestinians, mostly women and children. Hospitals have been targeted and many health care workers have been killed. As mentioned in the WCK statement, almost 200 aid-workers have sacrificed their lives in their selfless attempts to serve the oppressed which has not moved the cold stone hearts of Western leaders to any action, till the killing of the seven WCK workers as their chief has a voice!

In spite of three British aid-workers being killed, the largest number from any one country, condemnation from the British PM has been very mild, to say the least. It was reported that David Cameron, the Foreign Secretary wanted a strong response but was prevented from doing so by No.10 Downing Street! It was also reported that more than 600 lawyers, including former justices of Supreme Court had written to the government stating that weapon exports to Israel must end because the UK risks breaking international law over a “plausible risk of genocide” in Gaza. Interestingly, the British government is refusing to release the legal advice received! Of course, Israel denies genocide. It is genocide or holocaust only when it happens to them!

It was hilarious watching a news programme where one of the ministers was giving the lame excuses that stopping weapon exports to Israel serves no purpose as British sales amounted to less than a percent of Israeli arm imports. He overlooks the principle involved and it is heartening note that it is not only Sri Lankan politicians who are bereft of principles! The disgraced former PM Boris Johnson has gone a step further by stating that it is shameful to call for UK to end arm sales to Israel. Rich, coming from a man who knew no shame during the pandemic, getting fined for having parties in No. 10 Downing Street!

In fact, many lost confidence in Rishi Sunak on the day after the Rochdale by-election which was held on 29th February, won by the pro-Palestinian candidate George Galloway, which was no surprise as nearly a third of Rochdale population is Muslim. Sunak made a statement outside No. 10 waning about the rise of Islamic extremism but did not care even to mention the catastrophe in Gaza despite it being the same day that 112 died and more than 750 people were injured when IDF fired at a crowd of starving Gaza citizens chasing for morsels of food from an aid-convoy.

IDF claimed that it only fired warning shots and deaths were due to trampling but medics reported that deaths were due to gunshot injuries. Why could not he say that he would make inquiries from Israel, at least? No inquiry seems to have been held regarding this barbaric act. Subsequently, a Canadian doctor working in Gaza declared that she had seen many children shot in the head and accused IDF of targeting children. Mans inhumanity to man seems to have no bounds!

How the West deals with Israel is diametrically opposite to how they dealt with us when we fought terrorism! I do not have to go in to details of their hypocrisy, as much has been written on the subject, except to remind how UK and France sent their Foreign Ministers to rescue the Tiger leader. They were sent off with a rebuff so that the job of eradicating terrorism could be completed. Of course, we had a few traitors of our own who belittled!

I am afraid that the massacre of the innocents and the hypocrisy of the West will continue as long as it suits their purpose. Unfortunately, we live in a world devoid of fairness!

Opinion

Is JVP/NPP signalling left and turning right?

By Lasanda Kurukulasuriya

Since their visit to India at the invitation of the Indian government in February, leaders of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna-led National People’s Power coalition have become the poster-boys and girls of a complicated Sri Lankan political landscape, in a pre-election period. The once-marginal parliamentary group’s leader is now viewed as a potential future president. Looking beyond the optics of the party’s ongoing image makeover, what is the message behind the Indian ‘invite?’

“The message is in the invitation” JVP/NPP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake said, on Sirasa TV. “Our response is that we are ready. We are not an extremist project (aanthika deshapalana viyapaarayak nove) We are a project ready to work with any state that will allow us to advance the aspirations of the people without conflicts.” Though AKD’s remarks in this interview by Wasantha Maasinhage on 15.02.24 were wide-ranging, the party has otherwise been reticent about discussions they had with Indian External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar, NSA Ajit Doval, Foreign Secretary Vinay Kwatra and others they met from 5th to 9th Feb. Asked what they discussed with the Indian government, JVP Propaganda Secretary Vijithat Herath is reported as saying their talks had been ‘mostly on regional security issues.’

It appears the JVP has not only moved away from its earlier anti-Indian rhetoric, but made a startling turnaround on Indo-Sri Lanka relations. On the subject of foreign policy, the JVP leader stressed the need to understand and accommodate India’s sensitivities in dealings with other countries. The following exchange is from the interview:

AKD: “India is most interested in Trincomalee and the North. We cannot progress without taking this into consideration, It’s like this – it’s not an ‘Indian’ project. The project has to be within our national policy framework, and within that, we should go for an agreement with India.”

Sirasa: What do you mean.. ‘agreement with India..’ – Without calling for tenders?

AKD: At the very least, call for tenders within India

Sirasa: Only within India.. ?

AKD: At the very least, only within India. That’s not how it’s done right now, is it? The first option should be, consider if we can do the project ourselves. Second option, can we find a state without links to India or China?

Third option is to do the project, within our policy framework, calling for tenders within India.”

Looking back at agreements entered into with India over the past couple of years however, it’s clear that several projects, some of which included a grant component, had conditions, requiring that they be implemented only by Indian companies. Some were defence related, like the project for setting up a Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre in SLN headquarters in Colombo, through an agreement with Bharat Electronics – a company under India’s defence ministry. Facing a crippling economic crisis in 2022, and in desperate need of a US$ 1 billion loan for emergency supplies, Sri Lanka was not in a position to negotiate as an equal partner with India. Terms were dictated by the regional hegemon, with its own strategic objectives in this location, that has become a geopolitical flashpoint.

Renewable energy

During this period, India also consolidated its hold on Sri Lanka’s renewable energy sector – to the dismay of the local industry. Among some controversial MoUs signed in March 2022, were the unsolicited wind power projects in Mannar and Pooneryn, approved by the BOI in February last year, to be given to Adani Green Energy Ltd. The CEB chairman (who later resigned) revealed at a COPE hearing in June 2022 that then president Gotabaya Rajapaksa was under pressure from Indian PM Narendra Modi, to give the project to the Adani group. Indian tycoon Gautam Adani is said to be a close associate of the Indian PM.

Scientists and environmental experts have with one voice condemned this project for its ruinous environmental impact. They point out it does not make economic sense either, with purchase price being negotiated in US dollars at many times the market rate, for a 25 year contract period. While it has been suggested that alternative locations with wind power potential could be sought, it is unlikely the Indian side will agree to this, because it is precisely the site’s location that makes it important to them. In 2021, India’s objections led to the suspension of a contract won by China through an ADB-backed competitive bidding process, for a renewable energy project on three islands off Jaffna. India offered a grant to carry out the same project, and an MoU was signed during a visit by Minister Jaishankar, 28-29 March 2022. This contract was signed last month with U-solar Clean Energy Solutions, chosen through a competitive bidding process for Indian firms, conducted by GoSL, according to The Hindu.

Against this backdrop, the JVP leader’s stance that project tenders should be called ‘only within India,’ becomes deeply problematic. Is he saying, that the lop-sided style of project structuring that emerged at the height of the economic crisis, will become a ‘principle’ in the NPP’s programme? Few would dispute his critique of the manner in which governments see-saw between India and China, with corrupt politicians seeking ‘deals’ (on projects) for personal gain. But his position that projects should, as a matter of policy, be given to Indian companies is naïve at best. While he says that a local contractor would be the first option for a project (‘to do the job ourselves’), wouldn’t there be a large project area outside the scope of local expertise, such as in advanced technology? Besides, giving Indian firms preference for important projects would amount to an unquestioning acceptance of Indian strategic calculations. How would the fallout of such a policy affect Sri Lanka’s foreign relations – especially if it claims to be ‘Non-Aligned,’ as NPP ideologues have suggested, in published articles?

Sovereignty concerns

Another problematic MoU signed in 2022 relates to a large INR grant for a Unique Digital Identity (SL-UDI) programme for Sri Lanka, based on the Indian Aadhaar system. At a press briefing on 14.07.23 State Minister of Technology Kanaka Herath announced that tenders had been called for the project, to collect face, eye, fingerprint and ‘several other biometric data’ of all persons, with bidding limited to large Indian companies. The data would be stored in a centralized system, and the government of India would oversee the software development, he said.

Though the JVP/NPP delegation on Feb. 6 visited the Unique Identification Authority of India (that issues the Aadhaar number) it has been silent about this part of its tour. It was Dissanayake who raised concerns over SL-UDI in parliament last year. He is reported to have said his party had no objection to the project, but had concerns over sovereignty and the protection of citizens’ data. The Frontline Socialist Party warned that giving an Indian company access to the population’s biometrics posed a national security threat. However, neither the JVP/NPP nor FSP addressed the risk nearer home, that once the population’s biometric data is collected by government in a centralized, state-controlled database, it could potentially be used for mass surveillance of the citizenry.

While government statements vaguely suggest this project will ‘modernize’ Sri Lanka and make the delivery of state services more efficient, there is a worrying lack of public awareness and debate on the issues surrounding the introduction of such a scheme. For example privacy concerns have not been addressed, nor the question of whether the UDI will be mandatory in order to get welfare benefits and other state services. In India the Aadhaar scheme has been the subject of many supreme court rulings on issues raised by civil liberties groups. The European Parliament in October 2021 voted to back a total ban on biometric surveillance, in accordance with a report from a parliamentary committee on civil liberties.

The Sri Lankan UDI project has been dogged by controversy from the outset. When State Minister Herath announced the call for tenders, he indicated that the software systems would be ‘installed under the full supervision of the Information and Communication Technology Agency of Sri Lanka (ICTA).’ Within days of his press briefing the Parliamentary Committee on Public Enterprise (COPE) exposed bigtime fraud and corruption at ICTA. Three months later AKD alleged in parliament that the tender process had been manipulated to the advantage of a particular company. The two Indian companies that bid for the contract have since then been reportedly disqualified.

As an opposition party, the JVP has often called out corruption in government. With elections on the cards, if it has set its sights on coming to power, it will have to live up to expectations of voters accustomed to its anti-corruption rhetoric and demands for transparency etc while in opposition. How will it navigate issues surrounding the ongoing Indian projects? It has been conspicuously silent on the subject. With regard to ‘Amul’s plans to buy NLDB and Milco’ however, Dissanayake told Sirasa, they had clearly expressed their opposition, and would protect the local industry.

The question arises as to whether the Indian side sought assurances that their plans would not be disrupted, in the event of a significant change in their power status. Was this possibly the thinking behind FSP’s Education Secretary Pubudu Jayagoda’s remarks posted on Youtube, where he asked “Was it a trap that was set to invite the JVP? They have the government party on side, so now they have to get round the opposition”?

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoOnly if Buultjens knew that teams have pulled out of rugby sevens!

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoMallika Hemachndra Jewellers offer a glittering new year with gold and smiles

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoHNB and Ideal Motors partner up once again to offer exclusive perks on Mahindra automobiles, Powerol generators

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSinhala and Tamil New Year auspicious times

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoWigneswaran considers himself best Tamil candidate to run for President

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoVietnamese billionaire Truong My Lan sentenced to death for $44bn fraud

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoThe $2bn dirty-money case that rocked Singapore

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days ago‘NSB continued to prove its resiliency within economic shudder’