Opinion

13th Amendment, fair political representation, and social-choice theory

by Chandre Dharmawardana,

chandre.dharma@yahoo.ca

The TNA is the main political party of the North. S. Shritharan was recently elected its leader and M. A. Sumanthiran, who is regarded by some as being “barely Tamil”, as one Eelamist resident in Canada put it, was sidelined. Sritharan’s vision, expressed in post-election speeches, demands the merger of the Northern and Eastern provinces; he rejects the 13A as being grossly inadequate to meet the aspirations of the Tamils. The political parties of Gajendra Ponnamblam, and of C. V. Wigneswaran takes an even harder public stand. All tactically reject 13A, even though they rush to India to support 13A when support for 13A weakens in the South. The positions taken by southern politicians regarding 13A are also merely tactical and opportunistic.

Ironically, 13A is already a part of Sri Lanka’s Constitution, with some parts of it implemented, and others in suspense, mainly due to a huge lack of trust across the Northern and Southern political formations. Even the Eastern Tamil leaders do not trust the Northern leaders.

While the minority leaders still seek the chimera of an Indian supervisory role, the majority-community politicians know that strong Indian interventions, even “parippu dropped from air” are no longer a part of the show. President Ranil Wickremasinghe was seated next to Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the latter’s inauguration, while no TNA leader was visible. Meanwhile, the provincial councils themselves have atrophied, with provincial elections not even considered worth the cost, under the current circumstances.

The Northern political leaders rightly believe that any government in Colombo will be a government of the Majority Community and that minority rights will NOT be protected under such a set-up, judging by past history. So, they aspire to have a separate government of their own as the “only effective approach”. However, this approach triggered the past history of communal politics and violence that led to terror and counter-terror. Finally, the TULF leaders, Sinhalese politicians, even the Indian Leader who fathered the 13A, and thousands of innocent civilians got wiped out.

If there is no trust, there can be NO federalism, nor an effective 13A. Even an independent Eelam, separate from a Sinhalé by a physical border is not viable, as the two neighbours will be continually at war, as is the case between India and Pakistan, or across and even within Indian states (e. g. Manipur), even though the “Indian Model”, like 13A, is claimed to resolve these conflicts. Furthermore, such “independent” states will be forced to join up with big powers and become mere pawns of global proxy wars. That is the end of their “self-determination”.

The TNA says, “We don’t trust the majority, so we want our own government; but the minorities who will be under us, i.e., Muslims of the East or any Sinhalese who live in our “exclusive homeland” must trust us. Just forget attacks on Muslims or Sinhalese minorities when the TNA was an LTTE proxy”! This “aspiration” for hegemony by Tamil leaders over other minorities will be rejected by the respective minorities, just as the Tamil leaders reject being ruled by the Majority that they do not trust.

Social-choice theory

How can we equitably allocate agents (or electoral seats) to represent a group of people within a unitary setup (with a total quota of 225 seats), or with subdivided setups (e. g., with provincial councils or federal states with quotas of seats reflecting minority groups)?

This question falls within a class of much studied mathematical problems in game theory, mathematical economics as well as in the theory of social choice. Intellectual giants like John von Neumann and other mathematicians pioneered these studies. However, the most important results relevant to our discussion here came from Blinski and Young as well as from Kenneth Arrow. The latter won the Nobel Prize for economics in 1972 for his theorems on “social-choice theory”.

Blinski and Young proved a theorem showing that any apportionment rule (or representation and devolution rule) that stays within an assigned quota (say, of seats) suffers from what is known as the population apportionment paradox. This states that unless the populations remain absolutely static, even if the minority has a decisively large rate of population growth, the majority still gains more representation (or more power) inexorably! There is NO fair apportionment scheme!

Blinsky and Young’s result was a surprising “no-go” theorem. However, Arrow’s theorem, formulated in 1951 was even more surprising and counter-intuitive. Arrow laid down five “self-evident” axioms (or rules) about what may be called the “Will of the People” to be represented. For instance, a key rule is that the preferences and aspirations of a group should be chosen only from the group members (and not from outsiders). Another axiom is that the “will of the group” must not be that of one particular person; this is known as the no-dictator rule. The other axioms are similar harmless-looking rules about the group having specific preferences (e.g., favouring a set of religious or cultural traits against another set), or having maverick members who have changed policies in the past on a specific preference, although now in accordance with the “will of the group”.

Arrow’s impossibility theorem

Kenneth Arrow proved that, in spite of the highly democratic and seemingly “fair” formulation of these axioms, no such fair representation is possible. This is known as Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem. This theorem states that mandating the preferences and aspirations of the group cannot be ensured while adhering to usual “democratic” principles of fair voting procedures!

The mathematical conclusion is that a selection of people making decisions for those who elected them can never be a rational or fair process, however wise or benevolent they are! Their decisions will be necessarily autocratic! Naturally, the minorities within any group, be it under the Sinhalese majority in the main government, or under the Tamil majority in the TNA government reigning over the North and the East, will discriminate against the minority in each case.

Every available constitutional representation that satisfies Arrow’s axioms (i.e., common-sense ideas of fairness) is a perverse one. There is no “will of the people” or a democratic way of representing it. This very painful conclusion, reached by mathematicians in the 1950s, has stood all critical attacks on it. For over twenty-two decades, political scientists for whom the concept of the “will of the people” is as sacrosanct as the geocentric universe was to the medieval church attacked it! Instead of disproving Arrow, similar impossibility theorems, no-cloning theorems, etc., have been established in quantum information theory and quantum mechanics.

Devising an electoral scheme is mathematically equivalent to an apportionment scheme. Instead of allocating seats on the basis of population (i.e., “The People”), one may consider allocating “seats” on the basis of votes. This leads to models based on proportional representation (PR) instead of apportionment.

Mathematicians have shown that PR leads to even more serious negative consequences than apportionment. A variety of paradoxes of the Blinsky and Young type have been established. A very serious conclusion is that even the mildest PR system will confer a disproportionate amount of power to the third largest party in parliament! The third largest party becomes the king maker and often comes into a coalition with the second-ranking party to become the government! The validity of these results from game theory in practical politics has been established by studies of the history of governments in Germany, Israel and Denmark where high levels of proportional government have been legislated.

In my opinion, a way around these problems is to abandon electoral methods and return to the method of SORTITION advocated by Aristotle and used in several Hellenic cities during the time of Pericles.

Sortition has been adopted today in various limited ways, especially for local or provincial governments, in Ireland, France, Belgium, Canada and even Mongolia. In the simplest sortition model one arbitrarily selects by lottery a group of people who constitute the parliament. While these legislators last only five or six years, it is the administrative service that persists. The sortition parliament is not claimed to represent the “will of the people”. The lottery may be open to all the people, or only to a selection defined by their public service, education etc., as specified by a parliament chosen initially by simple sortition. That is, the first sortition parliament may enact more elaborate sortition models, but ensuring that the random element implied by sortition is never negated.

The sortition model ensures that the same set of corrupt politicians do not continue to get elected every time by controlling the list of candidates as well as the vote-gathering infrastructure which favours existing parties that have accumulated much wealth, by hook or crook. It also eliminates demagogues as the election is by lottery.

In other words, SORTITION ensures that a “system change” occurs every time. It ensures that political crooks, their henchmen and progeny do not entrench themselves and hold onto power over decades and decades, be it in the North or the South. I had given a discussion of the sortition model in a previous article in the Island (02-01-2023). It may also be accessed via the web (https://thuppahis.com/2023/01/02/crunchtime-resolving-sri-lankas-political-dilemma/ The applicability of the sortition model to the political problems in the USA has been discussed in the Harvard Review of politics (https://harvardpolitics.com/sortition-in-america/).

Opinion

M. D. Banda: Memories of Appachchi – II

(Part I of this article appeared yesterday (March 12)

Insights into a political career Prior to this period, for a very long time, Appachchi had always resided at Shravasti while he was in Colombo. For some time at Shravasti, his roommate was his friend, Mr. U.B.Wanninayake, Minister of Finance (1965 – 1970). Mr Wanninayaka too was well known for his honesty and integrity. Like Appachchi, he, too, possessed an unblemished political record. (I later married his youngest daughter, Swarna, who maintained her father’s honour and she herself lived a modest, unpretentious and a simple life as a government school teacher for 35years. She now leads a quiet life in retirement).

On our occasional visits to Shravasti as children, Mr Wanninayaka would give up his bed for us and move to another room. We loved to stay over at Shravasti mainly because of thescrumptious food. The food at home was good too but consisted mainly of rice and curry or local fare such as hoppers, string hoppers and pittu. At Shravasti we were served bacon and eggs and other Western food which made it feel like a hotel. It felt like a different world. It is there that I saw a spring bed for the first time. We jumped on these beds in glee.The period 1965-1970 was the pinnacle, the golden era of Appachchi’s political career. Hewas the Minister of Agriculture and the all-round development in the agricultural sector was remarkable as vouched for by the reports of The World Food and Agriculture Organisation,The Asian Development Bank and our own Central Bank. The unprecedented increase in paddy production by 38%, the introduction of potato cultivation and popularising the growing of chillies, etc., contributed to the vast development in the Agricultural sector during Appachchi’s tenure as minister of Agriculture.

The 2nd Cabinet of Ceylon formed in June 1952. Prime Minister, Dudley Senanayake, H. W. Amarasuriya, M. D. Banda, P. B. Bulankulame, A. E. Goonesinha, Senator Oliver Goonetilleke, J. R. Jayewardene, M. C. M. Kaleel, C. W. W. Kannangara, John Kotelawala, V. Nalliah, S. Natesan, E. A. Nugawela, G. G. Ponnambalam, Senator Sir Lalitha Rajapaksa KC) , A. Ratnayake, R. G. Senanayake, C. Sittampalam, and Senator Edwin Wijeyeratne

I happened to be at our Wijerama Rd, residence during this hectic period of activity in Appachchi’s life, and got the opportunity to accompany my father on some of his official visits to every nook and corner of the island to observe, first hand, the progress of the flagship programme of the Dudley government, the Food Drive. I was amazed by his knowledge and thorough understanding of the ground situation. The officials of theDepartment of Agriculture still speak with admiration of the way in which he interacted with the farmers and officers.

Although he had to be away from Colombo for 3 or 4 days a week, Appachchi never missed a single Cabinet meeting. Walter Jayawardene (Editor) mentioned in a newspaper article that Prime Minister Dudley was so keen to be updated on the progress of the Food Drivethat on days when Appachchi was due in Colombo, he postponed having his lunch or dinner until MD arrived.

The outstation trips with Appachchi at that time involved incredibly long journeys, and Appachchi used to start snoring in the rear seat of the car even before we reached the Kelaniya bridge! He must have been so exhausted. When we went to places likeAnuradhapura or Nuwara Eliya, we spent the night at the Prime Minister’s official residence,the Lodge. He must have had the full approval of the PM. Secretary to the PM, BradmanWeerakoon, would have done the required coordination. The beds in the lodge were obviously so comfortable that one fell asleep instantly! Fortunately, Appachchi slept in a separate room, otherwise, his snoring would have kept me awake the whole night. It goes without saying that the food was excellent. Before going to bed, Appachchi would come into check on me. “Cover yourself well, Puthe, and if you need anything, ring this bell” he would say.

Early in the morning he set out to check on the progress of the Food Drive in that particular area,and ended up attending the meetings scheduled in the Kachcheries the same evening. The GA who organised the visit, sat beside the Minister throughout the proceedings. Appachchi never failed to visit the livestock farm at Ambewela and the potato farm at Bopaththalawa whenever he visited Nuwara Eliya.

The Cabinet of Ministers with Her Majesty Elizabeth the Second, Queen of Ceylon. the photograph was taken in April 1954. The Queen was 28- years-old at the time. He was the Minister of Education during 1952-56. Seated (From left ) Hon. Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, Hon. E. A. Nugawela, Rt. Hon. Sir John Kotelawala (Prime Minister), Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II, Hon. J. R. Jayewardena, Hon. M. D. Banda, and Hon. P. B. Bulankulame Dissawa. Standing (From left) Hon. Dr. M.C.M. Kaleel, Hon. E. B. Wikramanayake, Hon. Sir Kanthiah Vaithianathan, Hon. R. G. Senanayake, Hon. S. Natesan, Hon. H. De Z. Siriwardana and Hon. C. W. W. Kannangara. The two European gentlemen standing on either side have not been named in the original caption for the photo.

After one such ministerial visit in the Kurunegala District, a high up official of the Agriculture Department had gone to the Rest House for the night. He was engaged in some activity in his room when the manager of the Rest House knocked on his door. ” I’m sorry sir, we’ll have to give the room to the Minister.” He said apologetically.

Unaware of all this, the minister walked in with his bags and found the officer packing his own bag to quit the room.”‘”Why are you packing your bag ?”, inquired the Minister. “The officer explained the situation. “Do you have a place to go to at this time of the night?”asked the Minister. “Must see” replied the officer. “No, don’t go anywhere. Stay here.There are two beds , and I can’t sleep on both beds, can I?” Pleasantly surprised, the officer agreed to share the room. “I will work till late, is that alright?”asked the Minister.After dinner, both retired to their room. Mr Banda got down some files from his car, and worked till 1 or 2 a.m. and finally switched off the light and went to sleep at 2 a.m. Relieved that he could at last sleep, the officer closed his eyes. But he couldn’t get a wink of sleep till 5 or 6 a.m. because the Minister started snoring! The Minister woke up around 6 a.m. had his breakfast and left for Anuradhapura before 7 a.m. for yet another official visit. When the officer related this story to his colleagues in the Head Office, no one believed him. But their Boss – the Director General of Agriculture, Mr. Ernest Abeyaratne –did. He had said, “It is not surprising at all. Only if he had acted otherwise would I be surprised!” This became a well-known anecdote in the department.

I remember travelling to Anuradhapura in a helicopter once and recall how thrilled I was when the pilot circled the aircraft around the Mihintale Chaithya thrice! Appachchi went to Pollonaruwe often and stayed at the Milk Board circuit bungalow. Once, appachchi had to attend a formal dinner at the Grand Hotel in Nuwara Eliya. He looked so smart in a full suit! He had a fine collection of exotic ties which were much admired by my friends when I wore them much later when I worked at Central Finance.

Many people have told me that appachchi was a unique person- unassuming, completely honest with integrity and sincere in whatever he said or did. He was warm -hearted and sensitive to the needs and suffering of others. Almost a god in the guise of a human, they said. I think this is true.He donated 35–40 acres of his private land to the government for the benefit of the people without claiming a cent as compensation. The most notable donation was the gift of 22 acres of prime land in the heart of the Polgahawela town when no land was available to build the Central College. This is a gift made to generations of children, already born and still unborn.

It is well known that Appachchi was a sincere and unwavering follower of both DS and Dudley Senanayake. The late Rukman Senanayake often said that M.D. Banda was Dudley’s most trusted comrade in the political world. As vouched for by Bradman Weerakoon too,Appachchi was Dudley’s own choice as his successor. The UNP Working Committee and the rank and file of the party shared this opinion as well. Despite all this, it was Appachchi himself who proposed JR’s name for the party leadership, as revealed by J.R at Appachchi’s funeral on 18 Sept. 1974.

After the unexpected demise of his leader and friend Dudley, Appachchi had no wish to continue in politics. Some of his younger friends like the MP for Dedigama, RukmanSenanayake, Prof. Karunasena Kodithuwakku and JRP Suriapperuma, came to Panaliya during week-ends, to revive and organise political activity but Appachchi’s heart, clearly, was not in it. The situation deteriorated further when his friend and colleague U. B. Wanninayaka,too, passed away.

Having said so much about Appachchi, I think it would be unpardonable if I fail to mention Amma, who was the unshakable strength that held our family together. Gracious and kindto all at all times and so unassuming that she hated being in the limelight. As far as I know, she has attended only two nationally important functions during Appachchi 30-year-long political career. The first such occasion was when Queen Elizabeth II visited Sri Lanka in 1953 and Appachchi was appointed the Minister in Attendance in his capacity as Minister of Education. Amma attended the Dinner that was given in honour of the Royal couple. The second occasion was when Srimati Indira Gandhi visited Sri Lanka as Prime Minister in 1967.Appachchi was then the Minister of Agriculture.

Something that is known only to our family and those close to us is that our Amma has never ever gone abroad – not even to India, although she had plenty of opportunities to do so ,had she chosen to accompany Appachchi on his numerous official visits abroad. Surprising,isn’t it? She and her sisters were old girls of Hillwood College, Kandy and once, as the wife of the Chief Guest , Hon M. D. Banda, she had the honour of distributing prizes at the Prize Giving of her Alma Mater. She was a truly wonderful mother who opted to stay home and look after their 7 children , graciously leaving her husband free to serve the nation.May they all – Appachchi , Amma and Berty Aiyya attain the supreme Bliss of Nirvana!

by Gamini Leeniyagolla

(Loku Putha)

Opinion

M. D. Banda: Memories of our Appachchi

(The 112th Birth Anniversary M. D. Banda fell on March 09.)

My memories of Appachchi when I was very little are nebulous. Whilst this may be the case with all little children, even ones with fathers who have regular 9-5 jobs, in my case, this was due to two additional reasons: our Appachchi lived mostly at “Shravasthi” the special residence for Lankan parliamentarians and not at our ancestral home home, in our village, Panaliya.

Additionally, we were all at boarding schools and spent nine months of the year in our respective school hostels. Thus, it was just during the holidays that the seven of us (my four sisters, two brothers and I) were at home, in Panaliya.

Looking back on this time, I realise that during most of my childhood my father was a Cabinet Minister, and one who was completely dedicated to his duties. He was conscientious to a fault, attending to ministerial duties, attending parliamentary sittings and cabinet meetings diligently. Appachchi first entered Parliament in 1947 when he was just 29 years old, and

was almost immediately appointed to the post of Parliamentary Secretary (Junior Minister) to the Minister of Labour and Social Services in May 1948. He was Minister of Labour and Social Services in February in 1950 and was again appointed to the same post by Hon Dudley Senanayake in March 1952. He became Minister of Education in June 1952 so that by the time I was born in December 1952, he was a senior member of the Dudley Senanayake Cabinet. I only fully realised how busy he must have been much later in life. As young children, it is our mother who gave us love and a sense of security by being fully present in our lives and seeing to all our needs, even when we were in school hostels.

Pivotal points

Our mother informed us one day, when I was around 3 or 4 years old , that Appachchi would be coming home that evening. Although my memories of this period are quite hazy, I recall very clearly the keen enthusiasm with which we awaited his arrival. Evening moved into night and his arrival was pushed back late and further late into the night. The moment I woke up the next morning I remember asking Amma where Appachchi was. “He came home very late last night but had to leave early this morning. He was a little annoyed with you, Lokka (everyone in the family calls me ‘Lokka’ even now), because you had parked your little car near the stairway, and Appachchi nearly tripped over it’ (this was before we had electricity in our home). My little heart was overwhelmed with sorrow for not only had I not seen Appachchi but I had inadvertently caused him injury with my careless parking of my miniature car.

This incident is indelibly etched in my mind because I believe that this was the first time in my life, that I experienced the agony of shattered expectations. Why I felt such intense pain then as a little child was perhaps because of how much I loved my father.

I was admitted to Hillwood College, Kandy at the age of three and a half and lived in the school hostel for three years. I clearly remember Amma visiting us at least once or twice a month with goodies and treats for us and our friends. I do not however have any clear memory of Appachchi visiting us during this time. At the time I didn’t realise that this was due to the busy life he led. At Hillwood, I had all the love and attention I needed from my four older sisters and my four older cousin sisters (our Lokuamma’s daughters).

My younger brother Senaka and I then entered Dharmaraja College, Kandy in 1961 . We were hostelers and attended school from the hostel. I clearly remember Amma visiting us regularly during this period too. I had my first real and meaningful conversation with Appachchi during this time: One day, our warden Mr Wimalachandra informed me that appachchi had come to take Senaka mallie and me out. We visited a relative of ours in Harispattuwa, had lunch with them and on our return journey to the school hostel, I told appachchi that I was playing cricket for the under 12 team at Dharmaraja College, and therefore needed a bat.

“Are you playing hardball?”

(I didn’t understand the question so I was silent)

“Is it the red ball?”

“Ah, yes.”

“Is it that kind of bat that you need?”

“Yes.”

“What is your position in the team?”

(I was once again silent)

“Are you an opening batsman? Or are you number 3, 4 or 5?”

“I can bat and bowl. I do both”

“Ah! Then you are an all-rounder. Number 6,7 – I will buy you this kind of bat. Play well till then.”

And the conversation continued in the vein but no bat has come to date!!!

Little did I know at the time that Appachchi was himself an outstanding cricketer, who represented the St Anthony’s College.Katugastota team and, later, for the Ceylon University College team, as an opening batsman. This is why he was so well versed with the game and was highly interested in my own cricketing capabilities. His passion for cricket was clear to us later on too because we all recall how he and his nephews, Bertie and Nimal, would listen to cricket commentaries and were glued to the radio when England and Australia played biennially for the famous Ashes trophy.

On the day of this momentous conversation, Bertie aiya (appachchi’s long-time Private Secretary, and his sister’s son; a lawyer by profession) had also come with Appachchi. It is from Bertie aiya that I learnt that day that the car they had driven up to Kandy in (an Austin A 70) belonged to Appachchi. I later learnt that Appachchi had not one but two cars (a Fiat 1400 too). Both cars were driven by Ranbanda, the chauffer, and were in Colombo because there was no one who could drive them at Panaliya. Amma always hired a car for her personal use at Panaliya, and would visit us in school in these hired cars, until her youngest brother Tissa came to live in our home at Panaliya. Tissa maama then drove amma around and would very often drive us to our school hostels. Another rather amusing memory from this same time goes like this: during a school holiday when I was in grade 6 at Dharmaraja College, Appachchi asked for my report card. I was 6 th

in class and therefore promptly and proudly took it to him. Appachchi scrutinised my report card carefully and said, not unkindly, ‘If you are 6 th in class with marks like this, all the other children in your class must be buffaloes’.

A shift in gears

I think I really got to know Appachchi well when Senaka malli and I entered Ananda College in Colombo. Although we first went to school from the school hostel, we would go to Appachchi’s official residence at Wijerama Mawatha every weekend. By this time, Amma too had moved to Colombo. Thus, between 1965 – 1970 , our home was at Wijerama Mawatha, with them. So, that is when I got the chance to interact closely with Appachchi. It was only at this time that it dawned on me that Appachchi was a powerful Cabinet Minister who was loved and respected by his constituents and the people of our country.

During this time, when I needed anything, I would go to his room early in the morning to remind him of what I needed. These requests were for the most part fulfilled.

Once I remember that I asked for track shoes (spikes) and Appachchi bought me a pair from abroad. When I needed money to buy a Tennis racket, he told me to go to the sports-ware store, ‘Chands’ at Chatham Street and select a racket. I received top treatment there and was even offered orange barley!

Then again I urgently needed ‘longs’ (trousers) to wear to school. “How many do you need?” he asked. Without thinking I said, “six”. “Why six?” he demanded. “There are only 5 days in the school week, no? Three would do.” Then he directed me to the ‘West End’ tailors’ shop in Pettah and asked me to get them stitched there.

It was Appachchi’s habit to take us to the Lake House Book shop every year and allow us to buy whatever we wanted. Considering that there were 7 of us, Senaka Malli and I chose just three or four books and took them to the counter, while our Chuti Malli Senerath, would bring a pile of books! “Do you want all these books?” Appachchi asked. Chuti Malli nodded “yes” and Appachchi bought all of them for him! This was probably because Appachchi himself loved books and wished to encourage the reading habit in his children.

When apachchi passed away in 1974, Senerath Malli was only 14 years old and I believe that the loss was greatest for him.

(To be concluded)

Loku Putha,

Gamini Leeniyagolla

Opinion

Social and Biological Landscape of Kidney Disease in Sri Lanka

World Kidney Day falls today

The Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) crisis in Sri Lanka represents one of the most formidable public health challenges of the twenty-first century, manifesting as a complex tapestry of environmental, social, and physiological factors. Unlike the traditional forms of kidney disease seen in urban centres—which typically stem from well-understood comorbidities like long-term diabetes and hypertension—the situation in the Sri Lankan ‘Dry Zone’ is defined by a mysterious and aggressive variant known as Chronic Kidney Disease of unknown aetiology (CKDu). This specific form of the disease has devastated the agricultural heartlands, particularly the North Central Province, for over three decades, yet it continues to evolve in its geographic reach and its socio-economic impact as of 2026. The persistence of this epidemic despite extensive international research highlights a profound gap in our understanding of how tropical environments and traditional occupational hazards intersect to damage human renal systems.

Historically, the emergence of CKDu was first noted in the late 1990s around the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa districts. What began as sporadic cases in rural hospitals quickly transformed into a localized epidemic, catching the medical community off guard because the patients did not present with the usual risk factors. These were not the sedentary, elderly populations usually associated with renal failure; rather, they were lean, active, middle-aged rice farmers.

The demographic specificity of the disease remains a chilling hallmark of the crisis today. It predominantly strikes men during their peak productive years, which triggers a catastrophic ripple effect through the family unit. When a primary breadwinner in a subsistence farming household falls ill, the family is thrust into a ‘poverty trap’ where limited resources are redirected toward transport to distant clinics, expensive nutritional supplements, and eventually, the gruelling routine of dialysis. This economic erosion often forces children out of school and into labour, perpetuating a cycle of systemic vulnerability that lasts for generations.

Intense scientific debate

The aetiology of the disease remains a subject of intense scientific debate and is currently viewed through a multifactorial lens. Researchers have moved away from the search for a single ‘smoking gun’ and are instead examining a lethal synergy of environmental triggers. Groundwater quality remains at the forefront of this investigation. The dry zone of Sri Lanka is characterized by high levels of fluoride and groundwater hardness, and it is theorized that the interaction between these natural minerals and anthropogenic pollutants—such as heavy metals from agrochemicals—creates a nephrotoxic cocktail.

The historical reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides in the ‘Green Revolution’ era of Sri Lankan agriculture is often cited as a major contributing factor. While direct links to specific brands of pesticides have been difficult to prove definitively, the accumulation of cadmium, arsenic, and lead in the soil and food chain continues to be monitored as a primary catalyst for the slow, progressive scarring of the kidney tubules.

In recent years, the discourse around CKDu has expanded to include the role of heat stress and chronic dehydration, exacerbated by the changing climate. Farmers in the North Central and Eastern provinces work long hours under an unforgiving sun, often without access to adequate quantities of clean drinking water.

There is growing evidence that repeated episodes of acute kidney injury caused by dehydration can lead to the permanent interstitial fibrosis characteristic of CKDu. This theory connects the Sri Lankan experience with similar ‘Mesoamerican Nephropathy’ seen among sugarcane workers in Central America, suggesting that CKDu may be a global phenomenon tied to the physical realities of manual labour in warming tropical climates. As global temperatures rise, the ‘heat stress’ hypothesis gains more urgency, positioning the Sri Lankan crisis not just as a local medical mystery, but as an early warning sign of how climate change impacts the health of the global agrarian workforce.

Geographical expansion of disease

The geographic expansion of the disease is a significant concern for the Ministry of Health in 2026. While Anuradhapura remains the epicentre, new ‘hotspots’ have been identified in the Uva and Northwestern provinces, as well as parts of the Southern hinterlands. This spread suggests that the environmental or behavioural triggers are more widespread than previously thought or that the migration of labour and changing agricultural practices are carrying the risk factors into new territories. The government has responded by shifting its strategy toward a more decentralized model of care. The establishment of the Specialized Nephrology Hospital in Polonnaruwa was a landmark achievement, providing state-of-the-art facilities for transplantation and dialysis. However, the sheer volume of patients means that the burden on tertiary care centres remains unsustainable. Consequently, the focus has shifted toward early detection through mobile screening units and the empowerment of primary healthcare centres to manage the early stages of the disease through aggressive blood pressure control and dietary management.

Water Security

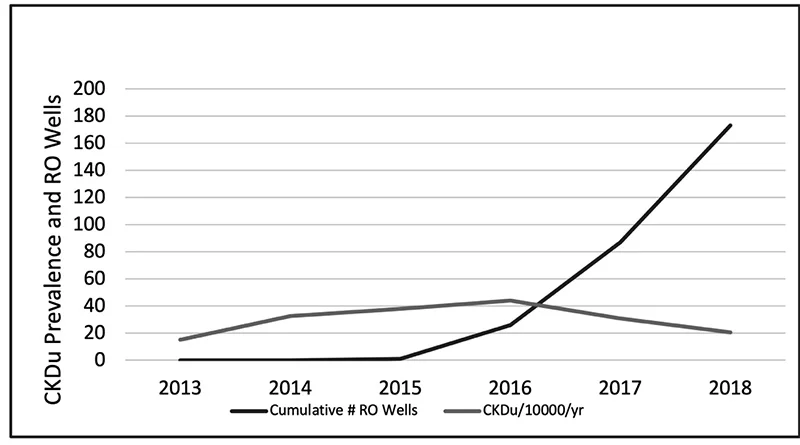

Water security has become the primary defensive strategy in the national fight against CKDu. The widespread installation of Reverse Osmosis (RO) plants across high-risk villages has been a transformative community-led intervention. These plants provide filtered water that is significantly lower in mineral content and potential toxins compared to traditional shallow wells. While the long-term efficacy of RO water in preventing new cases is still being evaluated through longitudinal studies, there is strong anecdotal and preliminary evidence suggesting a decline in the rate of new diagnoses in villages that have had consistent access to filtered water for over a decade.

However, the maintenance of these plants remains a challenge, as rural communities often lack the technical expertise or the consistent funding required to replace membranes and ensure the water remains safe for consumption over the long term.

Beyond the biological and environmental dimensions, the CKD situation in Sri Lanka is deeply tied to the social fabric and the psychological well-being of the rural population. There is a profound stigma attached to the disease; in some areas, families hide a diagnosis for fear that it will affect the marriage prospects of their children or lead to social isolation.

This fear often drives patients toward traditional healers or unregulated ‘cures,’ which can sometimes exacerbate kidney damage through the use of heavy-metal-rich herbal preparations. Addressing the ‘fear factor’ through community education and the normalization of regular screening is as essential as any medical treatment. Furthermore, the mental health of caregivers—often women who must balance farming, household duties, and the intensive care of a bedridden relative—is a neglected aspect of the crisis that requires urgent policy attention.

Need for paradigm shift

As we look toward the future, the resolution of the CKD crisis in Sri Lanka will require a paradigm shift in how the state manages its agricultural and environmental resources. The transition toward organic or ‘low input’ farming is being discussed not just as an ecological goal, but as a public health necessity to reduce the chemical load on the soil and water. Simultaneously, the push for universal access to pipe-borne water is the only permanent solution to the groundwater problem. The current situation in 2026 is one of cautious optimism tempered by the reality of a massive existing patient load. While the ‘mystery’ of CKDu may never be reduced to a single cause, the integrated approach of clean water, early detection, and social support offers a roadmap for mitigating the impact of this devastating epidemic.

The resilience of the Sri Lankan farming communities, supported by robust scientific research and empathetic governance, remains the greatest asset in overcoming a disease that has for too long defined the landscape of the Dry Zone.

The Northwestern Province of Sri Lanka, particularly within the districts of Kurunegala and Puttalam, has emerged as a critical front in the national battle against chronic kidney disease. Unlike the early epicentre in the North Central Province, the Northwestern region faced a delayed but rapid surge in cases, largely attributed to its unique hydro-geochemical profile.

The groundwater in areas such as Polpithigama and Nikaweratiya is characterized by high levels of calcium and magnesium, leading to extreme water hardness that, when coupled with fluoride, has been statistically linked to accelerated renal damage. As of 2026, the strategy for this province has shifted from reactive medical treatment to a massive expansion of safe drinking water infrastructure, reflecting a policy acknowledgment that the quality of the ‘input’ into the human body is the single most controllable variable in the CKD epidemic.

Clean water projects

Central to this effort is the National Water Supply and Drainage Board’s Regional Support Centre for the North-Western Province, which has accelerated its goal of achieving near-universal pipe-borne water coverage. A primary focus has been the Anamaduwa Integrated Water Supply Project, a multi-billion-rupee initiative designed to serve over 80,000 residents across the most vulnerable divisions. By transitioning communities away from shallow, untreated agricultural wells and toward centralized, treated surface water systems, the project aims to bypass the nephrotoxic minerals inherent in the local bedrock. This shift is not merely a matter of convenience; it is a life-saving intervention. Early longitudinal data from 2024 and 2025 suggests that in villages where pipe-borne water has replaced groundwater as the primary source for over five years, the rate of new Stage 1 CKDu diagnoses has begun to plateau, providing the first tangible evidence that infrastructure development can decouple agricultural livelihoods from the risk of kidney failure.

Reverse Osmosis Water Supply Wells and The Reduction of Incidence of CKDu in the North central Province (Source: Kidney disease, health, and commodification of drinking water: An anthropological inquiry into the introduction of reverse osmosis water in the North Central Province of Sri Lanka by de Silva and Albert 2021)

Indispensability of RO plants

While large-scale projects provide a long-term solution, the ‘interim’ role of community-based Reverse Osmosis (RO) plants remains indispensable in the Northwestern hinterlands. These plants, often managed by local community-based organizations (CBOs) with technical oversight from the government, serve as the primary defence for remote settlements that the pipe-borne network has yet to reach. The operational success of these RO plants is increasingly tied to a new model of ‘Water Safety Trust.’

Surveys conducted in 2025 indicate that the reduction of CKD in these areas depends heavily on consistent maintenance; when filters are changed regularly and brine disposal is managed correctly, the resulting ‘soft’ water significantly reduces the metabolic stress on the kidneys of the local farming population. However, the province still faces the challenge of ‘water commodification,’ where the cost of filtered water can occasionally burden the poorest families, highlighting the need for continued state subsidies to ensure that clean water remains a universal right rather than a luxury.

The reduction of CKD in the Northwestern Province is also being driven by a more sophisticated integration of water management and occupational health. Recent initiatives have begun to combine the provision of clean water with ‘cool zones’ and hydration advocacy for farmers working in the intensive heat of the dry zone. There is an increasing understanding that it is not just the quality of water that matters, but the quantity and timing of consumption to prevent the sub-clinical acute kidney injuries that precede chronic failure. By 2026, the regional health authorities have integrated water quality testing with mobile renal screening,

creating a data-driven approach where water projects are prioritized for ‘red-zone’ villages showing the highest incidence of early-stage disease. This holistic strategy marks a transition from viewing CKD as a medical mystery to treating it as a manageable environmental health hazard, with the Northwestern Province serving as a vital testing ground for these integrated interventions.

Biochemical landscape

The biochemical landscape of the Northwestern Province’s water crisis is defined by a sophisticated and lethal interaction between naturally occurring minerals and the human renal system. At the molecular level, the primary concern is the synergistic effect of fluoride ions and water hardness, which is predominantly caused by high concentrations of calcium and magnesium cations. While fluoride is often discussed in isolation, recent research in 2025 and 2026 emphasizes that its toxicity is profoundly amplified when it enters the body through ‘very hard’ water (typically exceeding 180 mg/L of calcium carbonate). When these ions meet in the slightly alkaline environment of the kidney’s proximal tubules, they can form insoluble nanocrystals of calcium fluoride or fluorapatite. These microscopic precipitates act as physical irritants, causing mechanical clogging and chronic inflammation of the delicate tubular basement membranes, eventually leading to the interstitial fibrosis that characterizes CKDu.

Furthermore, the ‘Northwestern profile’ of groundwater often includes the presence of glyphosate—a common herbicide—which scientists now believe acts as a carrier or ‘chelating agent.’ Glyphosate has the chemical ability to bind with calcium and magnesium ions in hard water, forming stable complexes that may protect the toxic elements from being filtered out by the body’s natural defences, allowing them to reach the kidneys in higher concentrations. This ‘Trojan Horse’ mechanism suggests that the disease is not caused by a single pollutant, but by a geochemical cocktail where the hardness of the water essentially ‘primes’ the body to be more susceptible to other environmental toxins. Interestingly, some studies have noted that magnesium-rich water may actually offer a slight protective effect compared to calcium-dominant water, suggesting that the specific ratio of minerals in a village’s well could determine its status as a ‘hotspot’ or a safe zone.

To combat these complex interactions, the maintenance of Reverse Osmosis (RO) plants has become a cornerstone of rural health policy, though it remains fraught with logistical challenges. As of 2026, the Ministry of Health has moved toward a ‘Uniform Regulation and Training’ model to address the high variability in water quality produced by community-managed plants. Without precise maintenance, RO membranes can become ‘fouled’ by the very minerals they are designed to remove, leading to a precipitous drop in filtration efficiency. Policy experts now advocate for a ‘Public-Private-Community Partnership’ where the government provides the technical sensors and remote monitoring technology, while local organizations handle day-to-day operations. This ensures that the Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) levels remain consistently below the 30-ppm threshold required to effectively ‘reset’ the mineral balance for residents who have spent decades consuming the region’s hazardous groundwater.

Fruitful environmental intervention

Ultimately, the reduction of CKD in the Northwestern Province is a testament to the power of targeted environmental intervention. By treating the water supply as a biological variable rather than just a utility, Sri Lanka is creating a global blueprint for managing ‘geogenic’ diseases. The transition from the ‘shallow regolith aquifers’—which are highly susceptible to both natural mineral leaching and agricultural runoff—to deeper, treated surface water sources represents the most significant shift in the province’s public health history. As these infrastructure projects reach completion, the hope is that the next generation of farmers in Kurunegala and Puttalam will be the first in decades to work their land without the looming shadow of a silent, water-borne epidemic.

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoHeat Index at ‘Caution Level’ in the Sabaragamuwa province and, Colombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Hambanthota and Monaragala districts

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe final voyage of the Iranian warship sunk by the US