Opinion

Whither Freedom of Speech?

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

We live in an era when it is becoming increasingly difficult to separate the truth from fiction. One may have assumed that advances in science and technology would make it easier for us to do so, but just the opposite has happened. Mainstream media have always been guilty of giving a slight slant to the truth to advance their agendas, but there were hardly any gross distortions of the truth. However, with the advent of social media and readily available broadcast sites like YouTube, truth has become a victim! In addition to the absence of statutory controls unlike in the case of the mainstream media, the sheer volumes of information disseminated by these sites make it almost impossible to monitor.

Rather surprisingly, it is not only individuals who are guilty of suppressing the truth; even international organisations are resorting to this tactic to suit the agendas of powerful nations bent on suppressing small nations. The most glaring example of this comes from none other than the United Nations itself: the supposed to be guardian of fairness! The disgraceful behaviour of the former Secretary General Ban Ki-moon defies description. The committee he appointed, the findings of which he endorsed, accuses Sri Lanka of many crimes but does not allow evidence to be challenged. In fact, Sri Lanka is denied even the right to examine the evidence. Everything is cloaked in secrecy for thirty years! In a court of law, the prosecution is obliged to provide the defence with all available data and has the right to challenge witnesses to check veracity. However, Ban Ki-moon’s UN is a law unto itself and we call it a Kekille judgement!

The right to freedom of speech at least allows us to vent our frustrations. However, it is much more important being a cornerstone of a civilised society. Not all of us think alike and we should be able to put our own points of view across but, unfortunately, pressure groups attempt increasingly to curtail free speech. Anyone questioning their views is ridiculed in social media and attempts are made to rewrite history. They forget that what is important is to learn from history rather than trying to rewrite it to suit their agendas. Of course, free speech should not mean the ability to state freely the absurd, profane and the obnoxious! It should be done within accepted norms.

The latest to join the brigades of suppression of free speech is a bank! No, it is not a bank in Sri Lanka; nor in one of the so-called totalitarian societies. Even more surprisingly, it is a bank in good old Blighty! A bank used by the Royalty! Coutts, based in London having three crowns as its logo, was started in 1692 and is the eighth oldest bank in the world. Often referred to as ‘The Queen’s Bank’, at least till last September, it serves the rich and famous. However, it is owned by the ‘high-street bank’ NatWest, which itself used to be a subsidiary of the Royal Bank of Scotland, which had to be saved from collapse by the tax-payer in 2008. It was one of the biggest banks in the world, considered too big to allow it to collapse, and has cost the British Exchequer £35.5 billion up to now. 39% of the shares are owned by the British Government. It may be the shame of that colossal failure, that RBS is now trading behind the name of its former subsidiary, NatWest!

In late June, Coutts decided to close the account of the British politician and broadcaster Nigel Farage as his views did not align with their values! True, banks can close accounts of crooks and racketeers but Farage is not one of those. Farge evokes strong emotions and is like Marmite; some love him and others hate him but even those who hate him for his views, do not consider him a crook. Therefore, Coutts has added a new dimension to banking; we close your accounts if you do not think like us! Is this not suppression of free speech?

Farage, perhaps, should be considered ‘The Father of Brexit’ as it was the train of events that he set in motion that led to the UK withdrawing from the European Union on 31 January 2020. He was a Member of the European Parliament from 1999 till Brexit and was the first person to expose waste and corruption of various branches of the European Union. Further, having sensed the direction of total integration the EU was heading, he wanted ‘independence’ for the UK and formed the UK Independence Party, of which he was the leader from 2006. As the pace for implementing Brexit was too slow, the crucial referendum being held in June 2016, he formed the Brexit party in 2019 which he led till 2021.

Those with bigger political clout, led by Boris Johnson, started their own campaign running parallel with Farage’s campaign. The combined effort led to the unexpected victory at the Brexit referendum and ‘Remainers’ continue to hate Farage even more than Johnson!

BBC, another flag waver for free speech, stands accused of having connived with Coutts as on 04 July, the day after its business editor was seen at a charity event with Alison Rose, the chief executive officer of Coutts’ owner NatWest, published an article stating that Coutts’ decision on Nigel Farage’s account did not involve considerations about his political views, stating “Nigel Farage fell below the financial threshold required to hold an account at Coutts, the prestigious private bank for the wealthy, the BBC has been told.” They did not name the source but, considering the timing, suspicion fell at the highest level and was considered by many a serious breach of client confidentiality. Further, Farage maintained that at “no point” had Coutts given him a minimum threshold.

Undaunted, Farage submitted a subject access request to Coutts, forcing out a 40-page document which he released to the press. This internal document from the bank, which contained minutes from a meeting of the bank’s Wealth Reputational Risk Committee, describes Farage as a “disingenuous grifter” who promoted “xenophobic, chauvinistic and racist views” and states “his views were at odds with our position as an inclusive organisation” with “risk factors including controversial public statements which were felt to conflict with the bank’s purpose”. Interestingly, it states that financially his account’s “economic contribution is now sufficient to retain on a commercial basis”. It refers repeatedly to Brexit, Trump and also Djokovic with known opposition to Covid vaccination!

The release of this document caused a furore, earning universal condemnation for the actions of Coutts’ from the Prime Minister downwards. I am sure most politicians were more concerned that ‘Freedom of Speech’ seems increasingly a farce in the UK!

On 20 July, Dame Alison Rose wrote a letter of apology to Farage and a cynic’s view is that she did this to save her job rather than to express her regret for the injustice to Farage! Interestingly, she states that the documents prepared for the Wealth Reputation Risk Committee “do not reflect the view of the bank”!

On 21 July, BBC changed the title of the original news item with a correction and on 24 July chief executive of BBC News and the business editor apologised to Farage. The following day, Alison Rose was forced to admit that it was she who had given information to BBC but said she was under the impression that she was just reiterating what was common knowledge! At this stage, the chairman of the NatWest group stepped in to say that though she had made a serious error of judgement, her continuing services are needed for the benefit of shareholders and hints that she could be punished by other means, perhaps reducing the annual bonus! However, following an emergency board meeting, Alison Rose resigned in the early hours of 26th morning.

It is rumoured that the resignation was due to government pressure. The city minister, who oversees financial institutions stated, “It’s not the job of the bank to tell us what to think or what political party we should support.” Freedom of speech seems to have got a reprieve!

British government is hurrying up with legislation to protect bank customers, which is yet another achievement of Farage, whilst Coutts, the Queen’s bank, is eating humble pie!

Opinion

Will computers ever be intelligent?

The Island has recently published various articles on AI, and they are thought-provoking. This article is based on a paper I presented at a London University seminar, 22 years ago.

Will computers ever be intelligent? This question is controversial and crucial and, above all, difficult to answer. As a scientist and student of philosophy, how am I going to answer this question is a problem. In my opinion this cannot be purely a philosophical question. It involves science, especially the new branch of science called “The Artificial Intelligence”. I shall endeavour to answer this question cautiously.

Philosophers do not collect empirical evidence unlike scientists. They only use their own minds and try to figure out the way the world is. Empirical scientists collect data, repeat and predict the behaviour of matter and analyse them.

We can see that the question—”Will computers ever be intelligent?”—comes under the branch of philosophy known as Philosophy of Mind. Although philosophy of mind is a broad area, I am concentrating here mainly on the question of consciousness. Without consciousness there is no intelligence. While they often coincide in humans and animals, they can exist independently, especially in AI, which can be highly intelligent without being conscious.

AI and philosophers

It appears that Artificial Intelligence holds a special attraction for philosophers. I am not surprised about this as Al involves using computers to solve problems that seem to require human reasoning. Apart from solving complicated mathematical problems it can understand natural language. Computers do not “understand” human language in the human sense of comprehension; rather, they use Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning to analyse patterns in data. Artificial Intelligence experts claim certain programmes can have the possibility of not only thinking like humans but also understanding concepts and becoming conscious.

The study of the possible intelligence of logical machines makes a wonderful test case for the debate between mind and brain. This debate has been going on for the last two and a half centuries. If material things, made up entirely of logical processes, can do exactly what the brain can, the question is whether the mind is material or immaterial.

Although the common belief is that philosophers think for the sake of thinking, it is not necessarily so. Early part of the 20th century brought about advances in logic and analytical philosophy in Britain. It was a philosopher (Ludwig Wittgenstein) who invented the truth table. This was a simple analytic tool useful in his early work. But this was absolutely essential to the conceptual basis of early computer science. Computer science and brain science have developed together and that is why the challenge of the thinking machine is so important for the philosophy of mind. My argument so far has been to justify how and why AI is important to philosophers and vice versa.

Looking at computers now, we can see that the more sophisticated the computer, the more it is able to emulate rather than stimulate our thought processes. Every time the neuroscientists discover the workings of the brain, they try to mimic brain activity with machines.

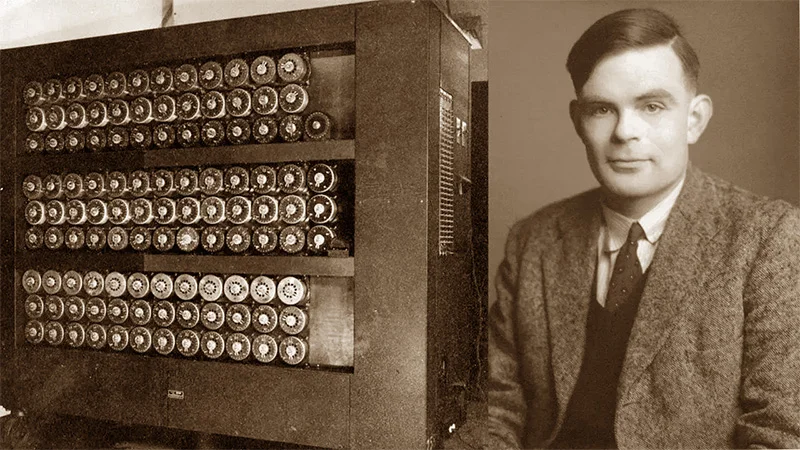

How can one tell if a computer is intelligent? We can ask it some questions or set a test and study its response and satisfy ourselves that there is some form of intelligence inside this box. Let us look at the famous Alan Turing Test. Imagine a person sitting at a terminal (A) typing questions. This terminal is connected to two other machines, (B) and (C). At terminal (B) sits another person (B) typing responses to the questions from person (A). (C) is not a human being, but a computer programmed to respond to the questions. If person (A) cannot tell the difference between person (B) and computer(C), then we can deduce that computer is as intelligent as person (B). Critics of this test think that there is nothing brilliant about it. As this is a pragmatic exercise and one need not have to define intelligence here. This must have amused the scientists and the philosophers in the early days of the computers. Nowadays, computers can do much more sophisticated work.

Chinese Room experiment

The other famous experiment is John Sealer’s Chinese room experiment. *He uses this experiment to debunk the idea that computers could be intelligent. For Searle, the mind and the brain are the same. But he warns us that we should not get carried away with the emulative success of the machines as mind contains an irreducible subjective quality. He claims that consciousness is a biological process. It is found in humans as well as in certain animals. It is interesting to note that he believes that the mind is entirely contained in the brain. And the empirical discovery of neural processes cannot be applied to outside the brain. He discards mind-body dualism and thinks that we cannot build a brain outside the body. More commonly, we believe the mind is totally in the brain, and all firing together and between, and what we call ‘thought’ comes from their multifarious collaboration.

Patricia and Paul Churchland are keen on neuroscientific methods rather than conventional psychology. They argue that the brain is really a processing machine in action. It is an amazing organ with a delicately organic structure. It is an example of a computer from the future and that at present we can only dream of approaching its processing speed. I think this is not something to be surprised about. The speed of the computer doubles every year and a half and in the distant future there will be machines computing faster than human beings. Further, the Churchlands’, strongly believe that through science one day we will replicate the human brain. To argue against this, I am putting forward the following true story.

I remember watching an Open University (London) education programme some years ago. A team of professors did an experiment on pavement hawkers in Bogota, Colombia. They were fruit sellers. The team bought a large number of miscellaneous items from these street vendors. This was repeated on a number of occasions. Within a few seconds, these vendors did mental calculations and came out with the amounts to be paid and the change was handed over equally fast. It was a success and repeatable and predictable. The team then took the sample population into a classroom situation and taught them basic arithmetic skills. After a few months of training they were given simple sums to do on selling fruit. Every one of them failed. These people had the brain structure that of ordinary human beings. They were skilled at their own jobs. But they could not be programmed to learn a set of rules. This poses the question whether we can create a perfect machine that will learn all the human transferable skills.

Computers and human brains excel at different tasks. For instance, a computer can remember things for an infinite amount of time. This is true as long as we don’t delete the computer files. Also, solving equations can be done in milliseconds. In my own experience when I was an undergraduate, I solved partial differential equations and it took me hours and a lot of paper. The present-day students have marvellous computer programmes for this. Let alone a mere student of mathematics, even a mathematical genius couldn’t rival computers in the above tasks. When it comes to languages, we can utter sentences of a completely foreign language after hearing it for the first time. Accents and slang can be decoded in our minds. Such algorithms, which we take for granted, will be very difficult for a computer.

I always maintain that there is more to intelligence than just being brilliant at quick thinking. A balanced human being to my mind is an intelligent person. An eccentric professor of Quantum Mechanics without feelings for life or people, cannot be considered an intelligent person. To people who may disagree with me, I shall give the benefit of the doubt and say most of the peoples’ intelligence is departmentalised. Intelligence is a total process.

Other limitations to AI

There are other limitations to artificial intelligence. The problems that existing computer programmes can handle are well-defined. There is a clear-cut way to decide whether a proposed solution is indeed the right one. In an algebraic equation, for example, the computer can check whether the variables and constants balance on both sides. But in contrast, many of the problems people face are ill-defined. As of yet, computer programmes do not define their own problems. It is not clear that computers will ever be able to do so in the way people do. Another crucial difference between humans and computers concerns “common sense”. An understanding of what is relevant and what is not. We possess it and computers don’t. The enormous amount of knowledge and experience about the world and its relevance to various problems computers are unlikely to have.

In this essay, I have attempted to discuss the merits and limitations of artificial intelligence, and by extension, computers. The evolution of the human brain has occurred over millennia, and creating a machine that truly matches human intelligence and is balanced in terms of emotions may be impossible or could take centuries

*The Chinese Room experiment, proposed by philosopher John Searle, challenges the idea that computers can truly “understand” language. Imagine a person locked in a room who does not know Chinese. They receive Chinese symbols through a slot and use an instruction manual to match them with other symbols to produce correct replies. To outsiders, it appears the person understands Chinese, but in reality, they are only following rules. Searle argues that similarly, a computer may process language convincingly without genuine understanding or consciousness.

by Sampath Anson Fernando

Opinion

Tradition, transformation, and China’s readiness as a global leader

Chinese New Year and the Spring Festival 2026:

The Chinese New Year, known domestically as the Spring Festival, is the most significant and widely celebrated cultural event in China. More than a public holiday, it represents a profound intersection of history, family, national identity, and future vision. As China prepares to celebrate Chinese New Year 2026, marking the Year of the Fire Horse, the nation does so with renewed confidence, cultural vitality, and strategic readiness, underpinned by the major achievements realized in 2025.

The festival reflects the harmony between continuity and change, demonstrating how traditions from thousands of years ago continue to guide and inspire the rhythm of modern life. It is a celebration not only of the calendar year but also of the enduring values of family, unity, renewal, and optimism.

Ancient Origins and Cultural Foundations

The origins of the Chinese New Year extend back more than 3,000 years, to early agrarian societies that organized their lives around lunar cycles. Early celebrations were closely linked to the agricultural calendar and seasonal transitions. Communities honored their ancestors, thanked nature for harvests, and performed rituals to seek prosperity, peace, and harmony in the coming year.

One of the most enduring and colorful legends associated with the festival is that of Nian, a mythical beast believed to appear at the turn of each year to terrorize villages. According to folklore, people discovered that Nian feared loud noises, fire, and the color red, which led to the invention of fireworks, firecrackers, lanterns, and red decorations—practices that remain central to the festival today.

The Spring Festival also follows the Chinese zodiac, a twelve-year cycle of animals, each symbolizing unique characteristics and influencing personality, fortune, and societal outlooks. These symbols continue to shape cultural expectations, social customs, and even business planning, illustrating the seamless blend of ancient wisdom with contemporary life. Despite centuries of change, the festival’s core values—family unity, respect for elders, gratitude, and hope for the future—remain unchanged.

The Year of the Fire Horse: Meaning, Dates, and Significance

Chinese New Year 2026 ushers in the Year of the Fire Horse, which will last from February 17, 2026, to February 5, 2027. The Horse is the seventh animal in the zodiac cycle and is traditionally associated with strength, independence, agility, vitality, and a pioneering spirit. The Fire element amplifies these qualities, symbolizing energy, courage, action, and transformation. Together, the Fire Horse embodies boldness, dynamism, and forward movement—traits mirrored in China’s economic, technological, and social aspirations.

Chinese New Year 2026 falls on Tuesday, February 17, 2026, with the official public holiday period in China running from February 15 to February 23, totaling nine days of national celebrations. The festivities extend beyond this period to 16 days, beginning on New Year’s Eve (February 16) and culminating with the Lantern Festival on March 3, 2026, when streets and public spaces glow with lanterns and dragon dances. Recent past and future Horse years include 1954, 1966, 1978, 1990, 2002, 2014, and 2026, each often associated with periods of significant movement, reform, or social transformation in Chinese history.

The Fire Horse year is regarded as particularly dynamic, characterized by rapid change, bold decisions, and a strong focus on independence—qualities that resonate with modern China’s trajectory toward global leadership.

Xiaonian: The Lively Prelude to the New Year

Before the Spring Festival itself, celebrations commence with Xiaonian (Little New Year), which marks the first stage of festive preparation. In northern China, Xiaonian falls on the 23rd day of the 12th lunar month, while in the south, it is celebrated on the 24th, reflecting centuries-old regional variations.

Xiaonian is traditionally linked to the Kitchen God, who reports the household’s deeds to heaven. Families offer sweets and symbolic foods, hoping for favorable blessings in the year ahead. Homes are cleaned thoroughly, sweeping away misfortune and making space for renewal. Though modern lifestyles have transformed certain rituals, Xiaonian retains its emotional significance, building anticipation and warmth for the grand reunion of the New Year. It represents the beginning of preparation, reflection, and hope.

Spring Festival Celebrations Across China

The Spring Festival spans 16 days, encompassing family reunions, regional fairs, cultural performances, and public spectacles.

Regional variations highlight China’s rich cultural diversity:

* Beijing and Northern China: Temple fairs are central, featuring folk music, opera performances, calligraphy, and crafts, alongside festive food stalls.

* Southern China (Guangdong, Fujian): Flower markets are a signature, with vibrant blooms symbolizing luck, prosperity, and renewal.

* Sichuan and Chongqing: Fireworks, spicy festival cuisine, and public performances dominate the celebrations.

* Historic provinces such as Shaanxi and Shanxi: Folk operas, paper-cutting, and drum performances preserve centuries-old traditions.

* Ethnic minority regions: Tibet, Yunnan, and Guangxi feature unique customs and performances that reflect cultural inclusivity.

Modern technology has amplified these traditions. Digital red envelopes (hongbao), livestreamed gala performances, and online marketplaces allow participation across cities and continents, showing how China merges heritage with contemporary innovation.

Key Traditions of Chinese New Year 2026

The Year of the Fire Horse comes alive through longstanding customs:

* Reunion Dinner: Families gather on New Year’s Eve, February 16, 2026, for sumptuous meals symbolizing unity and abundance.

* Home Decoration: Cleaning homes, hanging red lanterns, placing couplets, and displaying auspicious symbols prepare the household for a prosperous year.

* Red Envelopes (Hongbao): Elders gift children and unmarried adults money-filled red envelopes, wishing prosperity and good fortune.

* Fireworks and Firecrackers: A centuries-old tradition used to ward off evil spirits and invite good luck.

* Lantern Festival: Concluding the celebrations on March 3, 2026, communities showcase elaborate lantern displays, dragon dances, and family gatherings, emphasizing light, joy, and renewal.

Chunyun: The Spring Festival Travel Rush

An integral aspect of the Spring Festival is Chunyun, the annual travel rush marking the return of millions to their hometowns. Known as the world’s largest recurring human migration, it underscores the importance of family reunion in Chinese culture.

For 2026, Chunyun is expected to surpass previous records. Official projections estimate 9.5 billion cross-regional trips, including 540 million rail journeys and 95 million air trips. The peak travel period coincides with the official public holiday from February 15 to February 23, creating enormous pressure on transport networks.

China’s high-speed rail system, digital ticketing platforms, and smart logistics infrastructure manage this vast movement efficiently. Beyond logistics, Chunyun represents a remarkable societal phenomenon: a demonstration of national cohesion, familial bonds, and the scale of modern China’s capabilities.

China’s Achievements in 2025: Foundations for Leadership

As the nation celebrates the Year of the Fire Horse, it does so on the back of a remarkable year of progress in 2025:

* Economic Growth: China’s economy surpassed 140 trillion yuan (≈USD 20 trillion), achieving around 5 percent GDP growth despite trade tensions. This demonstrates resilience, scale, and structural stability.

* Technological Advancements: Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, high-speed rail, space exploration, and advanced manufacturing have propelled China into global leadership across key innovation sectors.

* Green and Sustainable Development: China reinforced its position as a leader in renewable energy, electric vehicles, low-carbon cities, and clean infrastructure, advancing the global energy transition.

* Global Engagement: Through trade, cultural diplomacy, and multilateral initiatives, China strengthened international cooperation, enhancing its role as a stabilizing global actor.

These accomplishments illustrate a nation capable of balancing tradition and innovation, social cohesion and global leadership.

Spring Festival as a Mirror of Modern China

The Spring Festival captures the essence of China’s evolution. From Xiaonian rituals to Chunyun, from the ancient zodiac to high-tech celebrations, the festival reflects a civilization that respects its past while confidently embracing the future.

The symbolism of the Fire Horse—energy, freedom, and action—resonates with the national trajectory: innovation-driven growth, inclusivity, cultural pride, and strategic global engagement. The festival highlights how tradition and modernity coexist, creating a society that is both rooted in history and prepared for the challenges of tomorrow.

Conclusion: Renewal, Reunion, and Global Readiness

Chinese New Year is more than a cultural event; it is a living manifestation of China’s identity and values. It represents family, tradition, renewal, and optimism, while showcasing the nation’s capacity for logistical sophistication, social coordination, and global engagement.

As lanterns glow in 2026, families reunite, communities celebrate, and cities shine—mirroring a nation that is culturally confident, economically resilient, technologically advanced, and globally influential. In the spirit of the Fire Horse, China embarks on the new year with bold energy, poised to act decisively, innovate continuously, and engage meaningfully with the world.

The Spring Festival of 2026 thus stands as a testament to China’s enduring cultural heritage and its readiness to contribute as a world leader in the decades ahead, combining the wisdom of tradition with the promise of a transformative future.

by Prasad Wijesuriya,

General Secretary, Sri Lanka – China Friendship Association

Opinion

The Walk for Peace in America a Sri Lankan initiative: A startling truth hidden by govt.

When we come to it

We, this people, on this wayward, floating body

Created on this earth, of this earth

Have the power to fashion for this earth

A climate where every man and every woman

Can live freely without sanctimonious piety

Without crippling fearWhen we come to it

We must confess that we are the possible

We are the miraculous, the true wonder of this world

That is when, and only when

We come to it.

· Concluding lines of the poem ‘A brave and startling truth’

(1995)

– Maya Angelou

Ven. Dr Melpitiye Wimalakitti Nayake Thera, Head Monk of the Wijesundararamaya, Asgiriya, Kandy, and the Chief Incumbent of the Gotama Viharaya Monastery, Fort Worth, Texas, USA, claims that the ongoing Texas to Washington Walk for Peace march led by the American monk of Vietnam origin Ven. Pannakara is ‘an initiative of ours’ (ape wedak). He made this claim during a recent podcast hosted by the well-known YouTuber and journalist Chamuditha Samarawickrema (CNB/February 5, 2026). The Huong Dao Monastery of Bhante Pannakara, who is leading the peace walk is close to the Gotama Viharaya Monastery of Wimalakitti Thera, who tells us that he has had a strong connection with Vietnamese monks and has already collaborated with them in many Buddhist activities.

Talking about Ven. Pannakara, Ven. Wimalakitti says that he is a pupil of senior Vietnamese bhikkhu Ven. Ratanaguna of the same Huong Dao Monastery in Fort Worth Texas. He is leading a team of 24 Buddhist monks from different countries in the (Southeast Asian) region including Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Bangladesh, Laos, etc., taking part in the Walk for Peace (from Fort Worth in Texas to Washington D.C.). It is going to be 2723 miles long according to Wimalakitti Thera. The Walk for Peace started on October 26, 2025 and is due to pass through 4 time zones and 10 states, braving extremes of weather and trekking through patches of harsh terrain.

It was 40 degrees Celsius in Texas, when they started. In seven days, the Peace Walkers reached Georgia in Atlanta. It was raining there. Then, they arrived in South Carolina, where it was cold, the temperature usually being under 20 degrees Celsius. By the time of the podcast with Chamuditha, the Walk for Peace was proceeding through the even colder North Carolina, the temperature barely rising above 1 or 2 degrees Celsius. Then, they reached Virginia with heavy snowfall, but the Walk went ahead nonstop.

The original plan was to walk 8 hours and cover 20 miles in a day. Now they want to do 10 hours a day and cover a targeted 40 miles. They hoped to have at least 20 participants in the Walk at any time. The whole Walk is expected to take 120 days and end on February 13, 2026.

America is a big democratic country, the monk says. The ordinary people are more interested in inner peace than in politics. There are 125 Sri Lankan Buddhist pansalas in America, 15 of which stand on the route of the continuing Walk for Peace. Sri Lankan monks resident in these monasteries, in partnership with monks from other countries, provide the Walkers with essential food, temporary lodgings, and hygienic facilities. They also work out security arrangements for the peace-walking monks in coordination with government and municipal authorities and Police.

Ven. Wimalakitti provides this information as a member and a director of the organising committee responsible for the Walk for Peace project. According to him, Ven. Pannakara takes part in an annual walk in India from Buddha Gaya to Kolkata (the capital city of India’s West Bengal state) as a dhutanga practice (one of the 13 strict ascetic practices recommended for bhikkhus in Theravada Buddhism that aim at perfecting austerity, mental purification, and renunciation). About 200 Buddhist monks join Bhikkhu Pannakara on this walk.

The dog now celebrated as Aloka started following Ven. Pannakara at Buddha Gaya and reached Kolkata with him. He followed the monk even to the airport. Bhikkhu Pannakara could not leave the dog behind in India and fly back to America. So, he canceled his flight and stayed back in India for eight months, during which he trained the dog and completed the paperwork necessary to take him to America with him. Once in America, Aloka sometimes started growling at people at first, because he was not used to the new environment. So, they put a pet cone around his neck to calm him while on the move. Now he participates in the Walk without the pet cone and walks beside Bhikkhu Pannakara at the head of the column of Walkers. The monk usually takes Aloka on a leash and occasionally, off-leash. Aloka had a paw injury during the walk and had to be hospitalised for a few days for surgery. He has rejoined the walk now. The dog has a car reserved for him to move with the walking party whenever he is unable to walk.

Ven. Wimalakitti Thera says he took part in six discussions held at the Huong Dao pansala when the peace walk was being planned. They had to discuss security matters with the Police. Concerns were raised about possible assassination attempts on Bhikkhu Pannakara. The dedicated monk said that he was ready to lay down his life for the cause of the Walk. Wimalakitti Thera said Bhikkhu Pannakara is only 37 years old.

At the beginning of the fourth week into the Walk, there was a serious traffic accident. The monks were walking along the shoulder of the road (near Dayton, Texas, east of Houston, on November 19, 2025) guided by a slow-moving escort vehicle (with hazard lights on). A truck hit the rear of the pilot car pushing it into the monks. The impact left two monks injured, one of them (Phra Ajarn Maha Dam Phommasan, aka Bhante Dam Phommasan) very seriously. The injured monks were airlifted to Houston for medical attention. Bhante Dam Phommasan had to undergo multiple surgeries, including the amputation of his leg. (The information given within parentheses in this piece of writing is added by me for clarity.)

On another occasion (in early January 2026, in Walton County, near Good Hope, Georgia) an unidentified protestor accompanied by a group of his supporters blocked the monks’ path (holding signs like ‘JESUS SAVES’, ‘Turn to Christ’; WARNING: ‘walking to hell’, ‘Hell awaits’, etc., but the people gathered there cheered on the monks, and asked the protestors to just move on). Ven. Wimalakitti (who was presumably on the scene) says that the police diverted them onto an alternative route. The unperturbed monks did not react to the disruptors and continued their walk in silence. The night routes were decided by the Police. The initial hostility petered out gradually, as thousands gathered on the roadsides to watch the monks walking and to listen to the sermons in the night.

(On Christmas Day 2025, the monks stopped at a church in Alabama, before entering into Georgia the next day.) Ven. Wimalakitti says that when Bhikkhu Pannakara made an address in the church that evening, it was filled to capacity, and his speech had to be broadcast on outdoor screens.

The Walk actually began as a dhutanga (please, see above) observance as Ven. Wimalakitti explains during the discursive podcast, which forms the basis of this essay. But, on the third day, the name was changed to ‘Walk for Peace’. Its purpose is non-religious and non-political. ‘Today is my day of peace’ is the theme. (Ven. Pannakara exhorts) “When you get up in the morning, say to yourself ‘Today is going to be my day of peace’”. When Wimalakitti Thera says “Ordinary Americans are really interested in Meditation (bhavana). They are much less interested in the dhamma”, he is making an obvious oversimplification that seems to be limited exclusively to the current Walk for Peace context.

WimalakittiThera claims that a single Pakistani individual from Texas ‘provides security for the Walk’. However much I tried, I couldn’t catch his name as the monk pronounced it. So I sought AI help. AI clarifies that ‘Based on the results of the 2025-2026 Walk for Peace from Texas to Washington D.C., the security and the logistics for the Buddhist monks are primarily handled by local law enforcement agencies (sheriffs and police departments) who secure the roads as the group walks’.(So, there is no mention of a Pakistani (American) providing security for the walk). The monk might be mistaken about the matter. But that piece of information is not so important. Though the monks have absolutely no political motives, the Sri Lankan monk thinks they expect (US President Donald) Trump to be there when they reach Washington, near the White House. A reception for the monks is scheduled to take place on that occasion with the participation of the Sri Lankan ambassador.

The highlight of the Chamuditha News Brief (CNB) podcast featuring Ven. Dr Melpitiye Wimalakitti uploaded on February 5, 2026 is his revelation of a well-kept secret, which is that the Sri Lankan monks living in America played the major pioneering role in organising the Walk for Peace across America project and that they wanted the Sri Lankan government to support it. The 17-member organising committee under the leadership of Ven. Wimalakitti, including the Vietnamese American bhikkhu Ven. Pannakara (who is now leading the Walk for Peace march) visited Sri Lanka in this connection in May 2025, that is, nine months ago. Ven. Wimalakitti showed the group photographs that the visiting monks took with prime minister Harini Amarasuriya, some ministers and other dignitaries. Still, ordinary Sri Lankans are unaware of this momentous event, it seems.

Unfortunately, there had not been any response to the monks’ request up to the day that Chamuditha did the podcast with Ven. Wimalakitti. The monk said that he broke off his participation in the Walk in order to visit Sri Lanka again for the express purpose of urging the Sri Lankan government’s participation in the Vesak celebration at Walk team leader Ven. Pannakara’s monastery in Texas in May. Ven. Wimalakitti said he gave the president and the prime minister (as I think he claimed) formal invitation cards requesting them to arrange for government delegates to attend the Vesak ceremony set to be held at the Huong Dao Monastery of Ven. Bhante Pannakara in Dallas, Fort Worth, Texas on May 26 this year (2026). He also wants them to grace the transport of relics from Sri Lanka. The monk was due to leave for America the night following the day of the programme with Chamuditha; but he had still got no reply from those important invitees. However,the Sri Lankan Ambassador in Washington is taking a great interest in this event, according to Ven. Wimalakitti.

At the end of the podcast, Ven. Wimalakitti voiced two important messages: “I want to say a word of diplomatic importance. This is a great opportunity for Sri Lanka, diplomatically speaking. This is a moment of awakening, not only for America but also for the whole world. All of you citizens of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka as a Theravada Buddhist state, can make your contribution to this global awakening. I urgently request that this great opportunity be not missed”. (The Walk for Peace, the peace pilgrimage across America, from Texas to Washington D.C., is performed by a group of Theravada Buddhist monks. It showcases the key Buddhist spiritual values of compassion, loving-kindness, non-violence, and peace that underlie Sri Lanka’s dominant religious culture. These values are a source of soft power for Sri Lanka in its diplomatic and cultural relations with the powerful United States of America.)

“Secondly, as Buddhists of Sri Lanka, please don’t criticise our monks or the Buddhist religion, simply because others do so. Please, think about this (insulting the monks and the Dhamma) with great equanimity. Both Buddhist monks and laypersons must keep updated about current trends. Some of our monks often attract criticism because they fail to adjust to changing times.”

By Rohana R. Wasala

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoA question of national pride