Features

Wage increase makes mockery of collective bargaining

by J. A. A. S. Ranasinghe

Productivity Specialist and Management Consultant.

This addendum to the topic is based on the incisive analysis of the plantation wages: Collective Bargaining or otherwise by Gotabaya Dasanayaka (GD) in The Island of 01st March 2021. The eminent labour legislation specialist, former Director General of the Employers Federation of Ceylon (EFC) has most undoubtedly hit the nail on the head drawing the attention of the readers to more sensitive aspects revolving round the importance of the time-tested collective bargaining systems prevailed in the determination of wages of the plantation workers for over three decades in particular as well as to the possible economic consequences, the new wage structure gives rise to the survival of the plantation industry in general.

Industrial Dispute Act No 43 of 1950 (ID Act)

The ID Act quite explicitly deals with the functions of the Commissioner of Labour (CL) under part 11 of the Act which says when an industrial dispute arose, it shall be the duty of the CL to refer such disputes for settlement by conciliation or by arbitration or by an Industrial Court including that of a District Court. It should be noted here that neither the Minister in charge of Labour nor the Commissioner of Labour (CL) nor the Deputy Commissioner of Labour (Industrial Relations) nor any other authorized person seems to have the gumption to abide by aforesaid conciliatory methods as envisaged in the ID Act, when the collective bargaining process of the plantation workers came to a deadlock a few weeks ago.

The most sensible course of action what the Minister or the CL should have done was to have recourse the dispute in question to a compulsory arbitration as per the provisions of the ID Act for a just and equitable award as articulated by GD. The reluctance on the part of the Minister to refer this sensitive issue to the compulsory arbitration is a moot point. Probably, he may have thought that the decision of the arbitration would not be favourable to the trade union demands. On the other hand, he may have thought that the reference to the arbitration is a time-consuming affair and the trade unions agitation is too severe to be ignored. However, it is crystal clear that the Minister had totally condemned the gist of the ID Act in toto by referring it to the Wages Board by circumventing all the bottlenecks in the pipeline for the first time in the history by creating a new precedent. It must be stated here that nowhere in the ID Act that an unfettered latitude is granted for the Minister to refer this labour dispute to the Wages Board. It is highly questionable as to why the Regional Plantation Companies did not challenge the Labour Minister’s arbitrary decision by way of a writ before the court and finally bore the brunt of the unconscious increase of the wages, which has far-reaching ramifications over the plantation industry and the smallholder sector.

Wages Board Ordinance (WBO)

Under section 8 of the WBO, the minister is empowered to establish Wages Board (WB) for any trade. It is a tripartite constituency representing the officials of the Labour Department, employers and employees of a particular trade. At present, there are 45 wages boards for different trades including that of plantation, agriculture and manufacturing industries and they receive minimum wages protection under this WBO. As regards the plantation sector, employees of rubber plantations 25 acres and above, coconut plantations 10 acres and above and tea plantations-no limit on acreage, are protected by the WBO. Though WB has been in existence for the last seven decades, the collective bargaining process initiated by the ID Act and the WBO functioned in tandem without interfering in each other’s territory.

As a matter of fact, collective bargaining process is more instrumental among the more organized sector where collective agreements are in force. By and large, the wage structure in the organized sector where collective bargaining operate is far superior to that of the establishments covered by the Wages Board. The minimum wages paid to employees covered by the WBO are conspicuously lower than the wages paid under the collective agreements. The Wages Boards are considered to be subsistence level wages as referred to above and in sectors where the trade unions are virtually non-existent. Hence, it is unprecedented that a matter which is subject to collective agreement was referred to wages board by the Minister of Labour in the annals of the labour movement of this country without realizing the repercussions that could arise. It is true that the plantation workers were covered by a Collective Agreement and periodically it has been renewed after collective bargaining. In a matter covered by Collective Agreement, if any dispute arose, the matter should have been referred to compulsory arbitration under the ID Act. However, in this instance, it is surprising that the issue was referred to the relevant wages board at the instance of the Minister of Labour.

Wage Impact on the industry

Mr. GD in his well-articulated article made a comparison between the wage structure of the different Wages Board in selected trades and the proposed daily minimum wage for the Tea and Rubber Growing and Manufacturing Trades and pointed out the huge disparity, if the proposed daily minimum wage of Rs. 1,000/= is paid across the board. Both the tea and rubber sectors are owned 70% by the smallholders, definitely the proposed increase will have a deleterious impact on the productivity of the tea and rubber sectors and the smallholders can ill-afford to bear the increased wage at this juncture. Right at the moment, a large number of rubber small holders in Kegalle, Kalutara and Ratnapura districts have abandoned their plots in the face of the exsisting wages and the dearth of labour. Right at the moment, Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) make a desperate attempt to contain the high cost of production and there will be an inevitable impact-detrimental to the well-being of the industry, in the face of the enhanced wages approved by the Wages Board.

GD in his article had incorporated the minimum wages applicable to selected eight trades to pinpoint the irrational disparity of wages and I would go further to highlight the inadvisability of enhancing wages through the wages board mechanism.

The Collective Bargaining process stipulated in the ID Act provided a reasonable effective mechanism to maintain healthy industrial relations and a healthy industrial peace and harmony for the last 30 years. Moreover, the sustainability of the industry and the commercial viability on the basis of labour productivity, profitability and the efficiency of operations were some of the key prime-movers at the collective bargaining table, which both parties took cognizance of seriously. Every Dick, Tom and Harry knew quite well that the government made a solemn pledge at the Presidential Election as well as the last Parliamentary election that the daily wage of the estate workers would be enhanced to Rs. 1,000/= as per the election manifesto (Chapter 10 of the Vistas of Prosperity and Splendour). It is this pledge that the government had to initiate at the last Annual Budget at the instigation of the labour trade unions in the estate sector.

Obviously, there are many obstacles both statutory and bureaucratic in the implementation of this pledge. The Commissioner of Labour (CL) who was well versed in the sustainability of the estate sector and the procedural initiatives involved as per the ID Act and Collective Bargaining Process was seen as a stumbling block and he had to be booted out by installing a provincial bureaucratic who was absolutely unaware of the commercial viability of the plantation sector, which is associated with many operational and financial ills.

It must be stated here in fairness to the former Commissioners of Labour in the calibre of Mr. G.Weerakoon and Mr. Mahinda Madihahewa who had served the Labour Department with distinction adroitly and they did not succumb to the political pressure and had the capacity to appraise both sides when critical labour issues arose in fairness to both parties but they relied heavily on the sustainability of the industry on a more priority basis in solving labour disputes. The Government realized that the collective bargaining process outlined in the ID Act was an impediment to the smooth implementation of the proposed wage structure. So, the government insidiously shifted from the time-tested mechanism of collective bargaining process to Wages Board to expedite the process. According to the grapevine circulating in the Labour Secretariat that three strong party acolytes were brought in as nominated members of the Minister to the Wages Board in order to ensure the easy passage of wage increment of Rs. 1,000/=.

Future Trends of the Labour Movement.

From the pattern of the signals hitherto displayed by the government that came into power in 2019, it appears that every vibrant sector would be confronted with insurmountable labour agitations. Firstly, the industry has been agitating to do away with the obnoxious requirement of paying Rs, 200,000/= in case of terminations under the Employment of Termination Act. The employers pointed out over a decade of time that it was difficult to bring in foreign investment with such a legislation. The government did a U Turn by enhancing the payment of compensation to Rs. 400,000/= instead of scrapping this piece of legislation. Secondly, the amount of workmen compensation in the event of a death of an employee due to a fatal accident was increased almost double, placing more financial burden to the employers at the instigation of the trade unions. The third scenario was the manner in which it deviated from the time-tested collective bargaining mechanism and imposed unbearable financial constraints by way of enhanced wages to the employees of the plantation industry. The industry is unaware of any other ill-logical motives to be moved in the pipe-line against the well-being of the industry in the foreseeable future. What would happen if the rest of the Wages Boards request enhanced wages quoting the unprecedented mechanism adopted by the government and the resultant chaos would be inevitable. Unlike those days, the trade unions have become more aggressive with their political affiliations with the government and the civil society too have extended their support to trade unions to win over their demands, as can be seen from the Colombo Port ECT deal. There is obviously writing on the wall that the country would be inundated with heaps of labour unrest issues with the wrong signals given by the government.

Financial assistance to RPCs

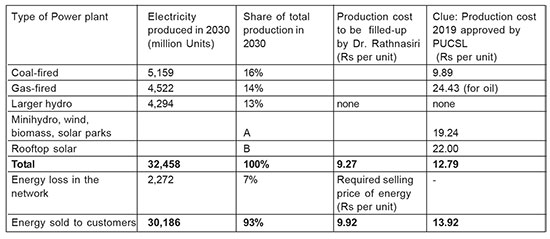

It is factually correct that Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) and smallholders were resisting the wage increase proposal on the ground that the financial resources do not permit them to incur this heavy expenditure. If this is the truth, nothing but the truth and the whole truth, the government has an inalienable duty to provide some financial assistance to RPCs by resorting to unorthodox avenues to alleviate its financial suffering even on short time basis. In this regard, Dr.Janaka Ratnasiri, a regular writer to The Island newspaper has made a pragmatic proposal in his feature dated 16th February 2021. He contends that export of tea is subject to a CESS levied at Rs. 10/- per Kg which works out to LKR 2.9 billion. Out of this, Rs. One billion is collected as tea promotion levy by Sri Lanka Tea Board from the exporters. Another 1% or 2.4 billion has to be paid to Brokers for conducting the auctions and carrying out quality control checks and certifying on samples received. These brokers comprising 8 Companies deserve it because they ensure that quality tea is exported. After paying taxes, the exporters are still left with a profit marginof about 65 billion annually. Dr. Janaka Ratnasiri argues that would be more prudent to share this profit among this plantation workers. Otherwise, it could be proportionately be distributed among the RPCs so that heavy financial implications arising out of this wage commitment could be mitigated.

Crises in the plantation industry

Consequent to the announcement of the new wage increase given to the plantation employees, there has not been any knee-jerk reaction from the plantation companies for the last one week. Their studious silence will have to be observed with much circumspection. Both the tea and rubber industries are on the verge of collapse owing to heavy financial implications and it is not clear as to how they absorb this unforeseen expenditure. It is certain that the Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) would continue to incur heavy losses with this wage commitment. It could be reasonably assumed that the production and its quality will be the immediate casualties and this trend, if any, does not auger well for the sustainability of the plantation industry.

It would have been the ideal opportunity for the Labour Ministry to harp on productivity-based wage model as a bargaining tool, which the ministry has pathetically failed to convince, given the sizable salary package. The word “productivity” is anathema to trade unions in Sri Lanka including that of the plantation trade unions. The ramifications arising out of this wage increase are far-reaching in character and it is advisable for the Employers Federation of Ceylon to educate the members of its broader ill effects by way of a public seminar and convey its dissatisfaction to the government.

The biggest casualty in the aforesaid wage episode is the gradual demise of the collective bargaining process that led to Collective Agreements and plantation companies will have to think twice whether there is any rationale in entering into Collective Agreements by giving enhanced wages and other perks, if ill-conceived mechanisms are adopted by the government to give enhanced wages through Wages Boards by ignoring time-tested collective bargaining mechanism.

(The views contained in this article are the professional views of the writer and he could be contacted on athularanasinghe88@yahoo.com)

Features

Making ‘Sinhala Studies’ globally relevant

On 8 January 2026, I delivered a talk at an event at the University of Colombo marking the retirement of my longtime friend and former Professor of Sinhala, Ananda Tissa Kumara and his appointment as Emeritus Professor of Sinhala in that university. What I said has much to do with decolonising social sciences and humanities and the contributions countries like ours can make to the global discourses of knowledge in these broad disciplines. I have previously discussed these issues in this column, including in my essay, ‘Does Sri Lanka Contribute to the Global Intellectual Expansion of Social Sciences and Humanities?’ published on 29 October 2025 and ‘Can Asians Think? Towards Decolonising Social Sciences and Humanities’ published on 31 December 2025.

On 8 January 2026, I delivered a talk at an event at the University of Colombo marking the retirement of my longtime friend and former Professor of Sinhala, Ananda Tissa Kumara and his appointment as Emeritus Professor of Sinhala in that university. What I said has much to do with decolonising social sciences and humanities and the contributions countries like ours can make to the global discourses of knowledge in these broad disciplines. I have previously discussed these issues in this column, including in my essay, ‘Does Sri Lanka Contribute to the Global Intellectual Expansion of Social Sciences and Humanities?’ published on 29 October 2025 and ‘Can Asians Think? Towards Decolonising Social Sciences and Humanities’ published on 31 December 2025.

At the recent talk, I posed a question that relates directly to what I have raised earlier but drew from a specific type of knowledge scholars like Prof Ananda Tissa Kumara have produced over a lifetime about our cultural worlds. I do not refer to their published work on Sinhala, Pali and Sanskrit languages, their histories or grammars; instead, their writing on various aspects of Sinhala culture. Erudite scholars familiar with Tamil sources have written extensively on Tamil culture in this same manner, which I will not refer to here.

To elaborate, let me refer to a several essays written by Professor Tissa Kumara over the years in the Sinhala language: 1) Aspects of Sri Lankan town planning emerging from Sinhala Sandesha poetry; 2) Health practices emerging from inscriptions of the latter part of the Anuradhapura period; 3) Buddhist religious background described in inscriptions of the Kandyan period; 4) Notions of aesthetic appreciation emerging from Sigiri poetry; 5) Rituals related to Sinhala clinical procedures; 6) Customs linked to marriage taboos in Sinhala society; 7) Food habits of ancient and medieval Lankans; and 8) The decline of modern Buddhist education. All these essays by Prof. Tissa Kumara and many others like them written by others remain untranslated into English or any other global language that holds intellectual power. The only exceptions would be the handful of scholars who also wrote in English or some of their works happened to be translated into English, an example of the latter being Prof. M.B. Ariyapala’s classic, Society in Medieval Ceylon.

The question I raised during my lecture was, what does one do with this knowledge and whether it is not possible to use this kind of knowledge profitably for theory building, conceptual and methodological fine-tuning and other such essential work mostly in the domain of abstract thinking that is crucially needed for social sciences and humanities. But this is not an interest these scholars ever entertained. Except for those who wrote fictionalised accounts such as unsubstantiated stories on mythological characters like Rawana, many of these scholars amassed detailed information along with their sources. This focus on sources is evident even in the titles of many of Prof. Tissa Kumara’s work referred to earlier. Rather than focusing on theorising or theory-based interpretations, these scholars’ aim was to collect and present socio-cultural material that is inaccessible to most others in society including people like myself. Either we know very little of such material or are completely unaware of their existence. But they are important sources of our collective history indicating what we are where we have come from and need to be seen as a specific genre of research.

In this sense, people like Prof. Tissa Kumara and his predecessors are human encyclopedias. But the knowledge they produced, when situated in the context of global knowledge production in general, remains mostly as ‘raw’ information albeit crucial. The pertinent question now is what do we do with this information? They can, of course, remain as it is. My argument however is this knowledge can be a serious source for theory-building and constructing philosophy based on a deeper understanding of the histories of our country and of the region and how people in these areas have dealt with the world over time.

Most scholars in our country and elsewhere in the region believe that the theoretical and conceptual apparatuses needed for our thinking – clearly manifest in social sciences and humanities – must necessarily be imported from the ‘west.’ It is this backward assumption, but specifically in reference to Indian experiences on social theory, that Prathama Banerjee and her colleagues observe in the following words: “theory appears as a ready-made body of philosophical thought, produced in the West …” As they further note, in this situation, “the more theory-inclined among us simply pick the latest theory off-the-shelf and ‘apply’ it to our context” disregarding its provincial European or North American origin, because of the false belief “that “‘theory’ is by definition universal.” What this means is that like in India, in countries like ours too, the “relationship to theory is dependent, derivative, and often deeply alienated.”

In a somewhat similar critique in his 2000 book, Provincialising Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference Dipesh Chakrabarty points to the limitations of Western social sciences in explaining the historical experiences of political modernity in South Asia. He attempted to renew Western and particularly European thought “from and for the margins,” and bring in diverse histories from regions that were marginalised in global knowledge production into the mainstream discourse of knowledge. In effect, this means making histories of countries like ours relevant in knowledge production.

The erroneous and blind faith in the universality of theory is evident in our country too whether it is the unquestioned embrace of modernist theories and philosophies or their postmodern versions. The heroes in this situation generally remain old white men from Marx to Foucault and many in between. This indicates the kind of unhealthy dependence local discourses of theory owe to the ‘west’ without any attempt towards generating serious thinking on our own.

In his 2002 essay, ‘Dismal State of Social Sciences in Pakistan,’ Akbar Zaidi points out how Pakistani social scientists blindly apply imported “theoretical arguments and constructs to Pakistani conditions without questioning, debating or commenting on the theory itself.” Similarly, as I noted in my 2017 essay, ‘Reclaiming Social Sciences and Humanities: Notes from South Asia,’ Sri Lankan social sciences and humanities have “not seriously engaged in recent times with the dominant theoretical constructs that currently hold sway in the more academically dominant parts of the world.” Our scholars also have not offered any serious alternate constructions of their own to the world without going crudely nativistic or exclusivist.

This situation brings me back to the kind of knowledge that scholars like Prof. Tissa Kumara have produced. Philosophy, theory or concepts generally emerge from specific historical and temporal conditions. Therefore, they are difficult to universalise or generalise without serious consequences. This does not mean that some ideas would not have universal applicability with or without minor fine tuning. In general, however, such bodies of abstract knowledge should ideally be constructed with reference to the histories and contemporary socio-political circumstances

from where they emerge that may have applicability to other places with similar histories. This is what Banerjee and her colleagues proposed in their 2016 essay, ‘The Work of Theory: Thinking Across Traditions’. This is also what decolonial theorists such as Walter Mignolo, Enrique Dussel and Aníbal Quijano have referred to as ‘decolonizing Western epistemology’ and ‘building decolonial epistemologies.’

My sense is, scholars like Prof. Tissa Kumara have amassed at least some part of such knowledge that can be used for theory-building that has so far not been used for this purpose. Let me refer to two specific examples that have local relevance which will place my argument in context. Historian and political scientist Benedict Anderson argued in his influential 1983 book, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism that notions of nationalism led to the creation of nations or, as he calls them, ‘imagined communities.’ For him, unlike many others, European nation states emerged in response to the rise of ‘nationalism’ in the overseas European settlements, especially in the Western Hemisphere. But it was still a form of thinking that had Europe at its center.

Comparatively, we can consider Stephen Kemper’s 1991 book, The Presence of the Past: Chronicles, Politics, and Culture in Sinhala Life where the American anthropologist explored the ways in which Sinhala ‘national’ identity evolved over time along with a continual historical consciousness because of the existence of texts such as Mahawamsa. In other words, the Sinhala past manifests with social practices that have continued from the ancient past among which are chronicle-keeping, maintaining sacred places, and venerating heroes.

In this context, his argument is that Sinhala nationalism predates the rise of nationalist movements in Europe by over a thousand years, thereby challenging the hegemonic arguments such as those of Anderson, Ernest Gellner, Elie Kedourie and others who link nationalism as a modern phenomenon impacted by Europe in some way or another. Kemper was able to come to his interpretation by closely reading Lankan texts such as Mahawamsa and other Pali chronicles and more critically, theorizing what is in these texts. Such interpretable material is what has been presented by Prof. Tissa Kumara and others, sans the sing.

Similarly, local texts in Sinhala such as kadaim poth’ and vitti poth, which are basically narratives of local boundaries and descriptions of specific events written in the Dambadeniya and Kandyan periods are replete with crucial information. This includes local village and district boundaries, the different ethno-cultural groups that lived in and came to settle in specific places in these kingdoms, migratory events, wars and so on. These texts as well as European diplomatic dispatches and political reports from these times, particularly during the Kandyan period, refer to the cosmopolitanism in the Kandyan kingdom particularly its court, the military, town planning and more importantly the religious tolerance which even surprised the European observers and latter-day colonial rulers. Again, much of this comes from local sources or much less focused upon European dispatches of the time.

Scholars like Prof. Tissa Kumara have collected this kind of information as well as material from much older times and sources. What would the conceptual categories, such as ethnicity, nationalism, cosmopolitanism be like if they are reinterpreted or cast anew through these histories, rather than merely following their European and North American intellectual and historical slants which is the case at present? Among the questions we can ask are, whether these local idiosyncrasies resulted from Buddhism or local cultural practices we may not know much about at present but may exist in inscriptions, in ola leaf manuscripts or in other materials collected and presented by scholars such as Prof. Tissa Kumara.

For me, familiarizing ourselves with this under- and unused archive and employing them for theory-building as well as for fine-tuning what already exists is the main intellectual role we can play in taking our cultural knowledge to the world in a way that might make sense beyond the linguistic and socio-political borders of our country. Whether our universities and scholars are ready to attempt this without falling into the trap of crude nativisms, be satisfied with what has already been collected, but is untheorized or if they would rather lackadaisically remain shackled to ‘western’ epistemologies in the sense articulated by decolonial theorists remains to be seen.

Features

Extinction in isolation: Sri Lanka’s lizards at the climate crossroads

Climate change is no longer a distant or abstract threat to Sri Lanka’s biodiversity. It is already driving local extinctions — particularly among lizards trapped in geographically isolated habitats, where even small increases in temperature can mean the difference between survival and disappearance.

According to research by Buddhi Dayananda, Thilina Surasinghe and Suranjan Karunarathna, Sri Lanka’s narrowly distributed lizards are among the most vulnerable vertebrates in the country, with climate stress intensifying the impacts of habitat loss, fragmentation and naturally small population sizes.

Isolation Turns Warming into an Extinction Trap

Sri Lanka’s rugged topography and long geological isolation have produced extraordinary levels of reptile endemism. Many lizard species are confined to single mountains, forest patches or rock outcrops, existing nowhere else on Earth. While this isolation has driven evolution, it has also created conditions where climate change can rapidly trigger extinction.

“Lizards are especially sensitive to environmental temperature because their metabolism, activity patterns and reproduction depend directly on external conditions,” explains Suranjan Karunarathna, a leading herpetologist and co-author of the study. “When climatic thresholds are exceeded, geographically isolated species cannot shift their ranges. They are effectively trapped.”

The study highlights global projections indicating that nearly 40 percent of local lizard populations could disappear in coming decades, while up to one-fifth of all lizard species worldwide may face extinction by 2080 if current warming trends persist.

- Cnemaspis_gunawardanai (Adult Female), Pilikuttuwa, Gampaha District

- Cnemaspis_ingerorum (Adult Male), Sithulpauwa, Hambantota District

- Cnemaspis_hitihamii (Adult Female), Maragala, Monaragala District

- Cnemaspis_gunasekarai (Adult Male), Ritigala, Anuradapura District

- Cnemaspis_dissanayakai (Adult Male), Dimbulagala, Polonnaruwa District

- Cnemaspis_kandambyi (Adult Male), Meemure, Matale District

Heat Stress, Energy Loss and Reproductive Failure

Rising temperatures force lizards to spend more time in shelters to avoid lethal heat, reducing their foraging time and energy intake. Over time, this leads to chronic energy deficits that undermine growth and reproduction.

“When lizards forage less, they have less energy for breeding,” Karunarathna says. “This doesn’t always cause immediate mortality, but it slowly erodes populations.”

Repeated exposure to sub-lethal warming has been shown to increase embryonic mortality, reduce hatchling size, slow post-hatch growth and compromise body condition. In species with temperature-dependent sex determination, warming can skew sex ratios, threatening long-term population viability.

“These impacts often remain invisible until populations suddenly collapse,” Karunarathna warns.

Tropical Species with No Thermal Buffer

The research highlights that tropical lizards such as those in Sri Lanka are particularly vulnerable because they already live close to their physiological thermal limits. Unlike temperate species, they experience little seasonal temperature variation and therefore possess limited behavioural or evolutionary flexibility to cope with rapid warming.

“Even modest temperature increases can have severe consequences in tropical systems,” Karunarathna explains. “There is very little room for error.”

Climate change also alters habitat structure. Canopy thinning, tree mortality and changes in vegetation density increase ground-level temperatures and reduce the availability of shaded refuges, further exposing lizards to heat stress.

Narrow Ranges, Small Populations

Many Sri Lankan lizards exist as small, isolated populations restricted to narrow altitudinal bands or specific microhabitats. Once these habitats are degraded — through land-use change, quarrying, infrastructure development or climate-driven vegetation loss — entire global populations can vanish.

“Species confined to isolated hills and rock outcrops are especially at risk,” Karunarathna says. “Surrounding human-modified landscapes prevent movement to cooler or more suitable areas.”

Even protected areas offer no guarantee of survival if species occupy only small pockets within reserves. Localised disturbances or microclimatic changes can still result in extinction.

Climate Change Amplifies Human Pressures

The study emphasises that climate change will intensify existing human-driven threats, including habitat fragmentation, land-use change and environmental degradation. Together, these pressures create extinction cascades that disproportionately affect narrowly distributed species.

“Climate change acts as a force multiplier,” Karunarathna explains. “It worsens the impacts of every other threat lizards already face.”

Without targeted conservation action, many species may disappear before they are formally assessed or fully understood.

Science Must Shape Conservation Policy

Researchers stress the urgent need for conservation strategies that recognise micro-endemism and climate vulnerability. They call for stronger environmental impact assessments, climate-informed land-use planning and long-term monitoring of isolated populations.

“We cannot rely on broad conservation measures alone,” Karunarathna says. “Species that exist in a single location require site-specific protection.”

The researchers also highlight the importance of continued taxonomic and ecological research, warning that extinction may outpace scientific discovery.

A Vanishing Evolutionary Legacy

Sri Lanka’s lizards are not merely small reptiles hidden from view; they represent millions of years of unique evolutionary history. Their loss would be irreversible.

“Once these species disappear, they are gone forever,” Karunarathna says. “Climate change is moving faster than our conservation response, and isolation means there are no second chances.”

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Features

Online work compatibility of education tablets

Enabling Education-to-Income Pathways through Dual-Use Devices

The deployment of tablets and Chromebook-based devices for emergency education following Cyclone Ditwah presents an opportunity that extends beyond short-term academic continuity. International experience demonstrates that the same category of devices—when properly governed and configured—can support safe, ethical, and productive online work, particularly for youth and displaced populations. This annex outlines the types of online jobs compatible with such devices, their technical limitations, and their strategic national value within Sri Lanka’s recovery and human capital development agenda.

Compatible Categories of Online Work

At the foundational level, entry-level digital jobs are widely accessible through Android tablets and Chromebook devices. These roles typically require basic digital literacy, language comprehension, and sustained attention rather than advanced computing power. Common examples include data tagging and data validation tasks, AI training activities such as text, image, or voice labelling, online surveys and structured research tasks, digital form filling, and basic transcription work. These activities are routinely hosted on Google task-based platforms, global AI crowdsourcing systems, and micro-task portals operated by international NGOs and UN agencies. Such models have been extensively utilised in countries including India, the Philippines, Kenya, and Nepal, particularly in post-disaster and low-income contexts.

At an intermediate level, freelance and gig-based work becomes viable, especially when Chromebook tablets such as the Lenovo Chromebook Duet or Acer Chromebook Tab are used with detachable keyboards. These devices are well suited for content writing and editing, Sinhala–Tamil–English translation work, social media management, Canva-based design assignments, and virtual assistant roles. Chromebooks excel in this domain because they provide full browser functionality, seamless integration with Google Docs and Sheets (including offline drafting and later (synchronization), reliable file upload capabilities, and stable video conferencing through platforms such as Google Meet or Zoom. Freelancers across Southeast Asia and Africa already rely heavily on Chromebook-class devices for such work, demonstrating their suitability in bandwidth- and power-constrained environments.

A third category involves remote employment and structured part-time work, which is also feasible on Chromebook tablets when paired with a keyboard and headset. These roles include online tutoring support, customer service through chat or email, research assistance, and entry-level digital bookkeeping. While such work requires a more consistent internet connection—often achievable through mobile hotspots—it does not demand high-end hardware. The combination of portability, long battery life, and browser-based platforms makes these devices adequate for such employment models.

Functional Capabilities and Limitations

It is important to clearly distinguish what these devices can and cannot reasonably support. Tablets and Chromebooks are highly effective for web-based jobs, Google Workspace-driven tasks, cloud platforms, online interviews conducted via Zoom or Google Meet, and the use of digital wallets and electronic payment systems. However, they are not designed for heavy video editing, advanced software development environments, or professional engineering and design tools such as AutoCAD. This limitation does not materially reduce their relevance, as global labour market data indicate that approximately 70–75 per cent of online work worldwide is browser-based and fully compatible with tablet-class devices.

Device Suitability for Dual Use

Among commonly deployed devices, the Chromebook Duet and Acer Chromebook Tab offer the strongest balance between learning and online work, making them the most effective all-round options. Android tablets such as the Samsung Galaxy Tab A8 or A9 and the Nokia T20 also perform reliably when supplemented with keyboards, with the latter offering particularly strong battery endurance. Budget-oriented devices such as the Xiaomi Redmi Pad remain suitable for learning and basic work tasks, though with some limitations in sustained productivity. Across all device types, battery efficiency remains a decisive advantage.

Power and Energy Considerations

In disaster-affected and power-scarce environments, tablets outperform conventional laptops. A battery life of 10–12 hours effectively supports a full day of online work or study. Offline drafting of documents with later synchronisation further reduces dependence on continuous connectivity. The use of solar chargers and power banks can extend operational capacity significantly, making these devices particularly suitable for temporary shelters and community learning hubs.

Payment and Income Feasibility in the Sri Lankan Context

From a financial inclusion perspective, these devices are fully compatible with commonly used payment systems. Platforms such as PayPal (within existing national constraints), Payoneer, Wise, LankaQR, local banking applications, and NGO stipend mechanisms are all accessible through Android and ChromeOS environments. Notably, many Sri Lankan freelancers already conduct income-generating activities entirely via mobile devices, confirming the practical feasibility of tablet-based earning.

Strategic National Value

The dual use of tablets for both education and income generation carries significant strategic value for Sri Lanka. It helps prevent long-term dependency by enabling families to rebuild livelihoods, creates structured earning pathways for youth, and transforms disaster relief interventions into resilience-building investments. This approach supports a human resource management–driven recovery model rather than a welfare-dependent one. It aligns directly with the outcomes sought by the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Labour and HRM reform initiatives, and broader national productivity and competitiveness goals.

Policy Positioning under the Vivonta / PPA Framework

Within the Vivonta/Proprietary Planters Alliance national response framework, it is recommended that these devices be formally positioned as “Learning + Livelihood Tablets.” This designation reflects their dual public value and supports a structured governance approach. Devices should be configured with dual profiles—Student and Worker—supplemented by basic digital job readiness modules, clear ethical guidance on online work, and safeguards against exploitation, particularly for vulnerable populations.

Performance Indicators

From a monitoring perspective, the expected reach of such an intervention is high, encompassing students, youth, and displaced adults. The anticipated impact is very high, as it directly enables the transition from education to income generation. Confidence in the approach is high due to extensive global precedent, while the required effort remains moderate, centering primarily on training, coordination, and platform curation rather than capital-intensive investment.

We respectfully invite the Open University of Sri Lanka, Derana, Sirasa, Rupavahini, DP Education, and Janith Wickramasinghe, National Online Job Coach, to join hands under a single national banner—

“Lighting the Dreams of Sri Lanka’s Emerging Leaders.”

by Lalin I De Silva, FIPM (SL) ✍️

-

News24 hours ago

News24 hours agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Editorial24 hours ago

Editorial24 hours agoCrime and cops

-

Editorial2 days ago

Editorial2 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?