Features

Vision of Dr. Gamani Corea and the South’s present development policy options

The ‘takes’ were numerous for the perceptive sections of the public from the Dr. Gamani Corea 100th birth anniversary oration delivered at ‘The Lighthouse’ auditorium, Colombo, by Dr. Carlos Maria Correa, Executive Director of the South Centre in Geneva on November 4th. The fact that Dr. Gamani Corea was instrumental in the establishment of the South Centre decades back enhanced the value of the presentation. The event was organized by the Gamani Corea Foundation.

The ‘takes’ were numerous for the perceptive sections of the public from the Dr. Gamani Corea 100th birth anniversary oration delivered at ‘The Lighthouse’ auditorium, Colombo, by Dr. Carlos Maria Correa, Executive Director of the South Centre in Geneva on November 4th. The fact that Dr. Gamani Corea was instrumental in the establishment of the South Centre decades back enhanced the value of the presentation. The event was organized by the Gamani Corea Foundation.

The presentation proved to be both wide-ranging and lucid. The audience was left in no doubt as to what Dr. Gamani Corea (Dr. GC) bequeathed to the global South by way of developmental policy and thinking besides being enlightened on the historic, institutional foundations he laid for the furtherance of Southern economic and material wellbeing.

For instance, in its essential core Dr. GC’s vision for the South was given as follows: sustainable and equitable growth, a preference for trade over aid, basic structural reform of global economy, enhancement of the collective influence of developing countries in international affairs.

Given the political and economic order at the time, that is the sixties of the last century, these principles were of path-breaking importance. For example, the Cold War was at its height and the economic disempowerment of the developing countries was a major issue of debate in the South. The latter had no ‘say’ in charting their economic future, which task devolved on mainly the West and its prime financial institutions.

Against this backdrop, the vision and principles of Dr. G.C. had the potential of being ‘game changers’ for the developing world. The leadership provided by him to UNCTAD as its long-serving Secretary General and to the Group of 77, now Plus China, proved crucial in, for instance, mitigating some economic inequities which were borne by the South. The Integrated Program for Commodities, which Dr. G.C. helped in putting into place continues to serve some of the best interests of the developing countries.

It was the responsibility of succeeding generations to build on this historic basis for economic betterment which Dr. G.C. helped greatly to establish. Needless to say, all has not gone well for the South since the heyday of Dr. G.C. and it is to the degree to which the South re-organizes itself and works for its betterment as a cohesive and united pressure group that could help the hemisphere in its present ordeals in the international economy. It could begin by rejuvenating the Non-aligned Movement (NAM), for instance.

The coming into being of visionary leaders in the South, will prove integral to the economic and material betterment of the South in the present world order or more accurately, disorder. Complex factors go into the making of leaders of note but generally it is those countries which count as economic heavyweights that could also think beyond self-interest that could feature in filling this vacuum.

A ‘take’ from the Dr. GC memorial oration that needs to be dwelt on at length by the South was the speaker’s disclosure that 46 percent of current global GDP is contributed by the South. Besides, most of world trade takes place among Southern countries. It is also the heyday of multi-polarity and bipolarity is no longer a defining feature of the international political and economic order.

In other words, the global South is now well placed to work towards the realization of some of Dr. GC’s visionary principles. As to whether these aims could be achieved will depend considerably on whether the South could re-organize itself, come together and work selflessly towards the collective wellbeing of the hemisphere.

From this viewpoint the emergence of BRICS could be seen as holding out some possibilities for collective Southern economic betterment but the grouping would need to thrust aside petty intra-group power rivalries, shun narrow national interests, place premium value on collective wellbeing and work towards the development of its least members.

The world is yet to see the latter transpiring and much will depend on the quality of leadership formations such as BRICS could provide. In the latter respect Dr. GC’s intellectual leadership continues to matter. Measuring-up to his leadership standards is a challenge for BRICS and other Southern groupings if at all they visualize a time of relative collective progress for the hemisphere.

However, the mentioned groupings would need to respect the principle of sovereign equality in any future efforts at changing the current world order in favour of all their member countries. Ideally, authoritarian control of such groupings by the more powerful members in their fold would need to be avoided. In fact, progress would need to be predicated on democratic equality.

Future Southern collectivities intent on bettering their lot would also need to bring into sharp focus development in contrast to mere growth. This was also a concern of Dr. G.C. Growth would be welcome, if it also provides sufficiently for economic equity. That is, economic plans would come to nought if a country’s resources are not equally distributed among its people.

The seasoned commentator is bound to realize that this will require a degree of national planning. Likewise, the realization ought to have dawned on Southern governments over the decades that unregulated market forces cannot meet this vital requirement in national development.

Thus, the oration by Dr. Carlos Maria Correa had the effect of provoking his audience into thinking at some considerable length on development issues. Currently, the latter are not in vogue among the majority of decision and policy makers of the South but they will need ‘revisiting’ if the best of Dr. GC’s development thinking is to be made use of.

What makes Dr. GC’s thinking doubly vital are the current trade issues the majority of Southern countries are beginning to face in the wake of the restrictive trade practices inspired by the US. Dr. GC was an advocate of international cooperation and it is to the degree to which intra-South economic cooperation takes hold that the South could face the present economic challenges successfully by itself as a collectivity. An urgent coming together of Southern countries could no longer be postponed.

Features

Writing a Sunday Column for the Island in the Sun

For nearly twenty years I have been writing a column for the Sunday Island. It has been a joyous ride for someone who is not a professional journalist, yet enjoying the thrill and enthusiasm of being a “deadline artist”, in however small a way. The ride began shortly after the 2005 presidential election when Rohan Edirisinha arranged for Kumar David and me to write for the Sunday Observer where Rajpal Abeynaike had just become the editor. Almost an year later, when Rajpal left the Sunday Observer, Vijaya Kumar, the Peradeniya Professor of Chemistry, arranged for us to switch to the Sunday Island where Manik de Silva was, and still is, editor.

After nearly sixty years in journalism, Manik still finds a different spark for each Sunday’s paper. He had been doing it weekly just as Prabath Sahabandu does it daily at The Island. They both have been very courteous and kind people to write for – especially for someone like me with a penchant for keep pushing the deadline until I make the final delivery. Besides Manik and Prabath, I have also had the pleasure of being tolerated by Malinda Seneviratne whenever he used to step in while Manik was away.

If a week is a long time in politics, as Harold Wilson prime-ministerially opined so many long decades ago, twenty years are an eternity in everything. And with Donald Trump everyday can be an eternity. Whether privileged or cursed, I have obliged myself to bear weekly witness to: the storied arrival and the humiliating departure of the Rajapaksas in Sri Lanka; the virtual demise of the once mighty Congress and the enthronement of its a-secular nemesis – the RSS – under Narendra Modi and the BJP in India; the perpetual swings between calm and chaos in Pakistan and Bangladesh; the post Brexit emaciation of Europe and Britain; three papal changes in Vatican; Jacinda Ardern’s graceful assertion of feminist motherhood power in national politics in little New Zealand; and the growingly disgraceful assertion of vulgar political masculinity by Donald Trump in the mighty United States of America, after the ephemeron of Barack Obama had fleetingly come and gone. Not to mention the rape of Gaza by the Netanyahu government in Israel, and Putin’s bloody Ukraine mockery of the already tattered legacy of the Soviet Union.

Besides politics, or rather both as part and extension of politics, the 21st century is becoming the century of climate change marked by recurrent furies of nature; of cultural upheavals; and technological leaps into the uncertain. As the years roll by, we lose our companions in the many marches we make in life, and I have had more than my share of writing obituaries for personal friends and political figures. Among the many, I especially remember my two Peradeniya friends – Sivendran and Lakshman Tilakaratne, and post Peradeniya companions – Paul Caspersz, Upali Cooray, Silan Kadirgamar and Kumar David. The latter three and me were pioneers of the Movement for Inter-Racial Justice and Equality (MIRJE) and its activities in late 1970s and 1980s.

Kumar was also a fellow columnist in the Sunday Island, equally pedagogical and polemical. He passed away in October 2024, when I was in Prague with my wife, Amali. Uvindu Kurukulasuriya tracked me down to give me the news. The next day, Friday early morning, we were leaving for Berlin by train, and I wrote my appreciation of Kumar on my laptop, during the four hours between Prague and Berlin, and finished it on time to meet my deadline with Manik in Colombo.

In light of that effort, I would think that the good reader will understand my desire to share the gratification I felt when I later came across the generous editorial note by Michael Roberts, while republishing my appreciation in his (Thuppahi’s) Blog: “This is a comprehensive VALE — wide-ranging, balanced and cast in incisive prose. Like the subject of discussion — the one and only Kumar — it marks the quality of education in all branches of education in old Ceylon in the mid-20th century.”

A matter of Education

The larger purpose in the citation above is to pay homage to “the quality of education in all branches of education in old Ceylon in the mid-20th century,” of which I am still a living beneficiary. Suffice it to say given the circumstances of my childhood and upbringing, I got exposed to and got hooked on – matters of nationalism, electoral politics and constitutional questions, quite early in life. Obviously, my understanding of them grew over time abetted by experience and aided by deliberate efforts of self-teaching. These were parallel pre-occupations that I kept going along with my studies in the science stream directed towards entering the university for a degree in engineering.

Once in the university I did not shy away from seizing opportunities for externalizing and articulating my evolving sociopolitical positions through writing, in debates and public speaking. I was already known in school as having the flair for writing and speaking in both Tamil and English, and I continued these pursuits at the university. A contemporary medical student who was in the same hall of residence with me in our first year took to describing me as a ‘writer, speaker and a part-time engineering student.’

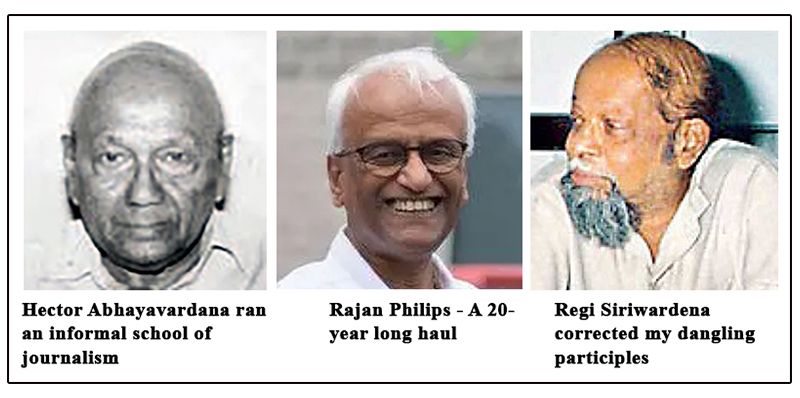

After university, while pursuing my career in Engineering, I joined the informal school of political journalism run by Hector Abhayavardhana and started writing for the political weekly The Nation that Hector edited. Hector Abhayavardhana was one of the more consummate left intellectuals of South Asia, shaped by nearly two decades of political living in India – both under colonial rule and after post-partition independence. He made a splash among Sri Lankan intellectuals and academics after his return to the island in 1961, and became the theoretician of the United Front politics during the 1960s and 1970s.

The Nation was the English chronicle of that politics, and it is there that Ajith Samaranayake, after leaving Trinity College, sharpened his writing tools before gaining national prominence. It so happened that it was after the funeral of Ajith Samaranayake that Vijaya Kumar apparently confirmed with Manik de Silva, his classmate at Royal College, that Kumar and I could start writing for the Sunday Island. Another interesting side to this is that Manik de Silva is also a nephew of Colvin R de Silva who was not only a frontline LSSP leader but also Sri Lanka’s greatest political rhetorician. Kumar has often blamed me that because of my alleged soft corner for Colvin, I have not been harsh enough in my criticisms of the 1972 constitution.

While I write my columns from Canada , I try to have my feet on the ground in Sri Lanka. I always meet up with Manik during my visits to Sri Lanka and often in the company of a sounding board of people that once included Kumar David and Diana Captain. Diana charmingly told me that she always likes my writing but doesn’t always agree with what I write. The usual regulars are NG (Tanky) Wickremeratne, Tissa Jayatileke, Chandini Tilakaratne, and occasionally Vijaya Kumar whenever he is in Colombo. Tanky even kept us in a room at the Orient Club until we exhaustively discussed a few of the more pressing problems facing Sri Lanka.

At a personal level I have benefited from the trove of insights offered by my sister-in-law Mano Alles, based on her vantage positions in the banking and financial circles. There is no politics without gossips and it is in the hands of the recipient to use them benevolently or malevolently. I have heard from AJ Wilson that NM Perera was known to be a lover of gossip during his salad days, at the LSE, in London. In my case, I am too much of an engineer to let slip personal stories into my narratives, except have them in background for internal validation. These are among the intangibles that make their way even in unseen ways into the making a column both in style and in substance.

Style and Substance

For style, I have benefited along the way from the kindness and learnedness of too many people. I owe my rudiments to my father and to my teachers at St. Anthony’s College, Kayts, and St. Patrick’s College, Jaffna. I have had my dangling participle corrected by Regi Siriwardena, with the nugget that Tolstoy too makes that error in the Russian. Just so you know, Regi knew his Russian, and a handful of other European languages, as well as he knew English. I never made the dangling mistake again, hopefully, and developed a keenness to look for it in the writing of others. Paul Capsersz red circled when I wrote ‘mentioned about’. Kumar would chide me early on as being too ‘effusive’ with my adjectives.

In Canada, I have been asked to use one sentence for no more than one idea. I heard from my daughter’s English teacher about the ‘range of sentences’ she was writing. She was 10 and I was 43, so I practised for a while – deliberately rewriting every other of my sentences to increase the range of them in a paragraph. Small sacrifice compared to Somerset Maugham, who was known for biting his thumb while searching for the fitting word, and not infrequently there was blood in his mouth before the word could arrive in his head.

Regi also used to tell us that we, Sri Lankans/South Asians, can be as good as anybody in expounding theories or writing commentaries in English, but the Achilles Heel of the second language is exposed when describing one’s personal experience or one’s observation of the physical surroundings and events. I have tried to overcome this shortcoming through my lived experience in Canada and interactions with those who write and speak with the license of the first language – more levity and freedom, and less caution and inhibition. I have also used my technical writing as an engineer and freelance writing as a columnist to be mutually informing and influencing.

Journalism as described in textbooks as a craft that marshals the attributes of creativity and enterprise, and is circumscribed by the pressure of deadline. Hence the coinage – deadline artists, in the 2018 HBO Documentary: Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists, dedicated to two of New York’s most celebrated tabloid journalists: Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill. Deadline and procrastination could be two sides of the same persona coin. The British writer Douglas Adams who is known for the quote “I love deadlines. I like the whooshing noise they make as they go by,” was also notorious for his procrastination as much as he was famous for his sharp wit.

My experience in writing a Sunday column does not involve any running around to gather facts and stories and hurriedly mould them into a story to meet the deadline. Yet the flow of adrenalin is palpable even in the laid back writing of a weekly column. My weekly routine is to look for a theme from among developing stories and then gather the relevant facts and opinions on the selected topic to develop a coherent argument. There is always Trump if there is no other topic.

Particular topics may benefit from premeditated ideas and pre-assembled information which will render a column comprehensive and compelling. Oftentimes, what I think is a good piece may not be liked as such by many readers. At least a partial explanation might be found in what Roland Barthes, the French literary critic, argued in “The Death of the Author” – to give the primacy of interpretation as much to the inclination of the reader as it is given to the intention of the writer.

No one writes a column hoping to change the world solely by the power of writing, although writing can be consequential if there are objective conditions that can bring about a sizable fusion between the writer’s intentions and the readers’ interest. Professional journalism like any other profession is meant to serve a functional purpose and not theatrical goals. Historically, the print medium emerged in Europe, as the Fourth Estate in a country’s realm, to hold to account in the public interest, the powers of the state and of the religious authorities. Reporting news and writing columns and editorials are part of fulfilling the trust to ensure accountability. Journalism is an integral part of the checks and balances of a social system that includes the state and its institutions, the civil society and its organs, and the market system and the private engines of economic growth.

The print medium has also played another historic role in the evolution of national societies. “Reading the morning newspaper is the realist’s morning prayer,” wrote Hegel highlighting the dominant status of the print medium in the 18th and 19th centuries after its beginning in the 17th. Benedict Anderson used this quote to premise his path-breaking thesis that the two main outputs of the print medium – the novel and the newspaper – have been the principal catalysts of the making of modern nations. A third factor is the pilgrimage of state functionaries – the transfer and territorial circulation of state officials, carrying the banner of the nation-state to every corner of its territory.

Sinhala and Tamil literati can relate to the role of the two instruments in the shaping of the language-based political consciousness that emerged in their respective communities in the 20th century, overarching the hitherto caste and kinship based building blocks of their social structures. There was a third and thinly overarching layer provided by the English medium newspapers that linked the island’s three communities, the Sinhalese, the Tamils and the Muslims, and created what Hector Abhayavardhana memorably called “the first anticipation of a Ceylonese Nation.” Alas, the first anticipation was never given a constitutional chance until the 13th Amendment.

As the 21st century gathers momentum, the decline and fall of the print medium is also gathering increased momentum. But the medium is not disappearing totally, and the newspaper part of it has adapted itself to go online to reach readers either in print or in i cloud. But unlike in print where the newspapers enjoyed a certain monopoly of space, they have no such monopoly on the internet where it is primitive competition for commercial recognition. In the social medium, there is no requirement for pre-qualification before “putting pen to paper,” that was once sine qua-non in the print medium. Any Tom, Dick and Harry can write anything in the social medium for any other Tom, Dick and Harry.

There is also no deadline pressure in the social medium, as news can break out concurrently with the story itself, unlike with the print medium that stays frozen between deadlines. The social medium is both invitingly open and compellingly divisive. There is no longer any commanding opinion in print, as it used to be, which will capture and hold the interest of a large segment of the reading public. Instead, the social medium offers a buffet of choices from each according to his biases to satisfy each according to his urges.

As for the morning prayer, the i phone has replaced the newspaper as a 24/7 office of readings – akin to the daily ‘office’, prayer readings, of the catholic priest. But the i phone also includes the newspaper if you are inclined to read it among so many other buffet choices. And as for me, I will continue writing, and leave it to the reader to digest what I have written while pretending dead, à la Barthes, the French essayist and philosopher, until the next Sunday.

by Rajan Philips ✍️

Features

Nihal ‘Galba’ Seneviratne (1934 – 2026)

In the nearly 42 years I have lived in the United States, I visited Sri Lanka regularly; in the early decades, maybe once a year and in more recent years, twice and even thrice a year. On each of these visits, I would choose to spend time with some of my parents’ friends, a practice that became more pronounced after 1999, because by that year, both my parents had passed away. There was a quartet that I kept in touch and called on consistently: Bishop Swithin Fernando, Scott Direckze, Kumar Chitty and ‘Galba’ Seneviratne.

During my one-on-one conversations with these wonderful, supremely accomplished human beings, almost always in their homes, I learned so much. I asked a lot of questions and they always responded enthusiastically. I learned about their childhoods, their education, their professional pursuits but most of all I learned about life: how to interact with others, how to develop greater empathy and compassion for others, how to live life guided by a moral compass and how to discover joy in a simple task or project. Now all these things I gleaned not from hearing a “lecture” by these good folks but by listening to and observing how they responded to the myriad challenges in their personal and professional lives.

The last of the quartet, Uncle Galba, passed away on January 6, 2026, about five months short of his 92nd birthday. He had lived a long, productive and incredibly accomplished life; mercifully, he escaped the horrors of a long, lingering and unforgiving illness at the end. For that blessing, I know all his loved ones remain so grateful. My initial contact with Uncle Galba was when I was a child through his son Jit, my near lifelong friend, who was two years ahead of me at Royal.

Our families lived a few hoots away from each other in our beloved Thimbirigasyaya neighborhood. As is often the case in Sri Lanka, our parents were friends and Jit’s parents and my parents had many mutual friends. Jit, another dear friend from the neighborhood, Siri, my brother Jehan and I all car pooled to Royal with our respective parents taking turns driving us. Many years later, Uncle Galba told me how he had lived in the Galle Fort as a young boy and how his family lived next door to my wife Shanthini’s mother’s family. He had wonderful memories of Shanthini’s mother and her siblings.

When I reflect back on my friendship with Uncle Galba, three aspects immediately spring to mind. First, his absolute zest and drive to meet people, all kinds of people, young, old, people of every stripe, people from completely diverse backgrounds, people with completely different interests. So he might attend the memorial service of a friend and then rush off to a Symphony Orchestra concert; or, he might attend an art exhibition and then take off to see a play at the Lionel Wendt; or, he would attend the launch of a friend’s book and then head to a dinner.

His ability to balance all these different social engagements was a thing of wonder and you would see him at the most unexpected events and places; always with a smile, always with his hand out to greet you and always inquiring how you were doing. You could sense how these social interactions rejuvenated him; concurrently, he certainly injected energy into those around him. His joie de vivre, his exuberant enjoyment of life was so infectious and so inspiring, something I would often tell Uncle Galba.

Of course, the second week of March every year was a special time for him, as it is for many of us, and his social engagements were at a peak as he would do the rounds at several of the Roy-Tho Tents. These social interactions meant that he was already to help those in need with a word of advice or recommendations on how to navigate a bureaucratic issue or place a call to an official to move a project along; in fact, the concept of a “letter from Galba” gained epic proportions among many of us for this very reason.

Second, his unstinting loyalty, devotion and love for Royal College. Uncle Galba belonged to the Group of 45, one of the most illustrious batches in the history of Royal College. Many members from the Group of 45 filled the ranks of Sri Lanka’s medical, legal, diplomatic, public service, financial, scientific and corporate sectors with great distinction. Uncle Galba was in that elite corps with his 33 years of service at the Parliament of Sri Lanka, culminating as Secretary General.

He served as the Secretary of the Royal College Union (RCU) for a number of years, chaired and served on numerous committees related to milestone events at Royal and then, finally, was appointed Vice President Emeritus of the RCU. He worked tirelessly to improve aspects of Royal that garnered the least attention and ensured that these areas were not neglected.

Third, his encyclopedic knowledge of events and personalities in his long, momentous life and his ability to relate them with flair and unbridled enthusiasm. One of the stories stood out from the many he relayed to me: his visit to North Korea with a delegation of Sri Lankan Parliamentarians. The extreme secrecy shrouding the entire visit, the exceedingly long and unnerving train journey to an unknown destination and then the dramatic meeting with North Korean supremo Kim Il Sung bordered on something from a John le Carré novel.

He also had an innate sense of curiosity and a thirst for what was going on both locally and globally on the political and economic fronts. His extended time living in Washington, D.C. to study operational aspects at the U.S. House of Representatives left him with both a fondness and abiding interest in American politics. Whenever I visited with him, he would ask me a series of questions about various political, legal and constitutional developments in the U.S. From his questions, I could see how he was comparing dimensions of the American and Sri Lankan political systems and how the two systems approached thorny challenges.

In closing, I have to reference Uncle Galba’s incredible love for his immediate and extended families. His grandchildren brought him such joy and he was so proud of all their accomplishments. To Aunty Srima, Jit and Shanika, thank you for sharing Uncle Galba with all of us and for allowing us to experience all his unique attributes. For me, Uncle Galba’s passing signals the end of an era in terms of my quartet of individuals from my parents’ generation; yet, another indication of the relentless march of time. In the meantime, I am grateful for all that I have absorbed from my friendship with Uncle Galba. Very grateful. Sujit CanagaRetna

Features

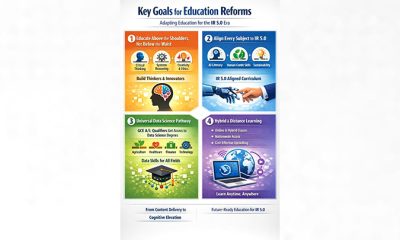

Surprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

The letter of appointment (as Secretary to the Ministry of Education and Higher Education and Directer-General of Education) was dated March 30, 1990. This sudden transfer was not quite expected and therefore somewhat puzzling. We were of course hearing of numerous problems in the Ministry of Education and Higher Education. But we had no inkling that we were going to be sent to deal with them.

This appears to be what had happened. The Minister told me later, that the President had indicated to him shortly before the shift, that there were serious problems in the education sector and the Ministry, and that he had decided to send him there to address them. “I am giving you Dharmasiri also,” the President had said. I regretted leaving Agriculture. So did the Minister. We had just got our teeth into the job and had a vision of accomplishing so many things. The regret therefore was not due to any personal reasons.

On the other hand we knew Education was not going to be an easy Ministry to handle. If one’s responsibilities included the education of 4.3 million children in over 10,300 schools, having a teaching staff of 192,000 teachers, including about 14,000 principals and senior deputies, and with eight Provincial Councils to deal with, it was not going to be easy. But that was not all. We also had responsibility for about eight Universities and 28 Technical Colleges and units. The Ministry was also the National Centre for activities connected with UNESCO and therefore had to perform a coordinating role with so many other Ministries and agencies.

There was however an initially disturbing feature. I have already recounted in a previous chapter the disquiet engendered in my friends when they heard that I was to be sent as Chairman and Director-General of Broadcasting. When the news got round that I was going to Education, a similar disquiet manifested itself. Again, I received a number of telephone calls inquiring whether it was true that I was being sent to the Ministry of Education and on my affirming it to be correct, I received expressions of concern and sympathy. In my entire career of close upon 37 years, these were the only two occasions when some of my friends drawn from a number of different backgrounds thought it fit to commiserate with me on an appointment.

I myself was aware, I Ike many others, that there was a great deal of public criticism of the Ministry during this time. There were complaints of delays, inefficiency, corruption and lack of care. I was however not prepared for both the breadth and depth of feelings, if the telephone calls I received were anything to go by. It was also disconcerting that the Ministry of Education of a country should enjoy such a dubious reputation. It was therefore with a degree of reservation and even unhappiness that I responded to the Minister’s invitation to come and see him at his official residence at Stanmore Crescent on Saturday, March 31. The Minister as was characteristic of him had already got down to work.

When I met him, he had on his table some four volumes of a recent ADB report on Sri Lankan Education. He had already skimmed through them and had made several pages of handwritten notes. These he handed over to me to get typed and make extra copies. I for my part had not even heard of these reports until I met the Minister. In my entire career I had never met, or even heard of a Minister who displayed Mr. Athulathudali’s speed of response to a new situation. I do not know whether the fact that he was a champion hurdler, at one time holding the Sri Lankan Public Schools’ record for the 100 yards hurdles, had anything to do with his ability to get off the blocks so fast, whatever the circumstances. The Minister and I discussed a number of general issues pertaining to education, and possible arrangements to be made in the Ministry. I left after about an hour and 15 minutes, clutching his precious notes.

On the morning of Monday April 2, 1990, I walked into the Ministry of Education and Higher Education housed in the storied building named “Isurupaya,” situated at Battaramulla within sight of “Tile Overseas School,” where many children of diplomats attended. The first curious feature I noticed was that nobody really seemed to expect me. I found my way into the spacious and elegant room meant for the Secretary, who was also the Director-General of Education.

It later transpired that some at least were waiting for the new Secretary to telephone and declare an auspicious time at which he would come. They were also planning some kind of reception. As mentioned in an earlier chapter, I have always dispensed with all these. For me, the auspicious time begins when the office is open for business.

When the appropriate officers discovered now with some concern that I had arrived and came to see me, one of the first things that I told them was that I would like to have a staff meeting that afternoon. I required the presence of all staff officers in the Ministry and the Departments and agencies under the Ministry, other than Higher Education. I had decided to have a separate meeting with them within the next day or two. The officers looked rather perplexed.

“You mean you want to meet the staff officers in the Ministry?” they inquired. I repeated my request. “But Sir, that would be about 125-130 staff officers. The conference room can take in only about a hundred,” they said. This revealed that the Ministry had probably not had a combined staff officers’ meeting for a long time. I was not prepared to let things off so lightly. I said, “Coming in I saw some nice trees in the premises. History shows that a great deal of education had taken place under trees. There is nothing to prevent discussions on education too, being conducted under trees.

Assemble everybody under a tree.” The officers looked shocked at this unorthodox approach, but when afternoon came, they somehow managed to squeeze in about 115 officers into the conference room.

The rest were either on leave or had gone out of Colombo.

During my as yet very brief stay of just a few hours in the Ministry, I noticed something quite disconcerting. This was the almost religious awe with which the Secretary was regarded and treated by senior officials of the various Education Services. There were also officers of the Sri Lanka Administrative Service, including those at Senior Additional Secretary level. They for their part treated you with respect, and certainly not with exaggerated awe.

The question that bothered me was as to why, educated and qualified people, quite a few of them with post-graduate diplomas and masters degrees should behave in this fashion. Why were they so cowed? Why had such a culture prevailed? Senior level officials would stand at the threshold of my room and would not come in. Even when invited they would take a few steps towards me and then stop and hesitate. It is not an exaggeration to state that some of them had to be literally coaxed to come up to me. In my entire 29 years of service, prior to this appointment I had not witnessed a phenomenon such as this. In due course I shared my thoughts with the Minister. By that time, he himself had noticed this whole culture of exaggerated respect and fear. This being the situation, it was no wonder that there were serious problems in education.

Laying down the framework

At my staff meeting in the afternoon, I said that since trying to understand the new Secretary would take time, which could be put to better use, difficult as the exercise was, I would try to analyze

my character and attitudes for their benefit. I made the following points:-

1. That I was a very direct person and that if I said something they should not waste time and energy looking for hidden meanings. I meant what I said and no more.

2. I expected the same direct response from others because I too had no time to contemplate the issue of hidden meanings.

3. I was used to always treat everyone with respect, and I expected the same respect and no more. I did not want anyone to bend in two. On the contrary obsequiousness irritated me.

4. All fears must be dispelled, and an open intellectual dialogue fostered very early.

5. Anyone had the latitude and right to disagree with me or for that matter with the Minister and to state that disagreement without any fear.

6. However when all disagreements and points of view had been taken into account and a decision reached, it was incumbent on everyone to carry out that decision, even though some may not be personally convinced.

7. I would like to hear and see good humour, laughter and enjoyment at work.

8. Avoidable delays would be a matter of concern.

9. In any dealings with me credibility was of the highest importance and should never be lost. We are all human and we all make mistakes, but mistakes should not be aggravated by the greater mistake of lying about them.

10. I was by nature, training and personal discipline both mild of character and patient. But it would be a grave mistake to confuse mildness with weakness , and it would be best that nobody put this to the test.

I have not had the occasion to make such an address ever before or after. But the situation in the Ministry really frightened me. I frankly told them about the opinion that professionals and educated people outside had about them as demonstrated by the telephone calls I had received. I asked them whether this was the image they wanted about themselves. They agreed not. “In any case, now the Minister and I are a part of you we are certainly going change this,” I said. “Otherwise, I shall certainly not want to serve here,” I concluded.

The rest of the meeting consisted of a briefing and dialogue on various matters of relevance to the educational sector. I think, I did manage to infuse some ease and good humour to the meeting, mainly because this was my natural style, as many public servants who had worked with me would vouch for. The whole exercise seemed to have had a cathartic effect, because one could see a visible loosening up, which resulted in loud and animated discussions after the meeting on the corridors. The Ministry that was as silent as the grave, seemed now to display considerable traces of life.

Right from the very beginning, the Minister followed a policy of open dialogue. He also believed in de-mystifying institutions and drawing out the talents of their people through open procedures. As in the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Co-operatives, discussions, meetings and conferences became animated, lively and thought provoking. Mr. Athulathmudali’s central concern was how to achieve the difficult task of overall quality improvement across the board, in all subject areas and disciplines. At the same time he recognized the importance of English and sought ways and means to expand the number of hours of English teaching, as well as improve teacher training in this area.

He was particularly concerned with the issue of confidence, in speaking the language. He introduced, papers at lower levels in English, Sinhala and Tamil and gave candidates the option of sitting for lower level papers in Any language, whilst they were sitting for the GCE “O” level examination. The intention was to take away the sense of failure from the minds of students, who might have failed papers at “O” level in these subjects. They would gain a sense of satisfaction if they received a certificate for a paper which they had passed at their own level of competence and achievement.

The graded Sinhala and Tamil language papers were mainly meant for Sinhala and Tamil students who wanted to acquire language skills in each others languages. This initiative became quite popular, judging from the numbers who sat these papers.

The Minister also saw the need to upgrade technical education. He rightly perceived the psychology of technical education, the fact that the community regarded it as a lesser vehicle for those who were not clever enough or bright enough to pursue academic courses. He wanted to change this mindset. He understood the Sri Lankan context where a “degree” was highly regarded. He therefore spent considerable time and effort in constructing a ladder for technical education, culminating in a Bachelor of Technology degree. His main purpose in doing this was his recognition of the importance of technical education for the future of the country and the necessity to bring down the virtual class barrier between academic and technical education.

(Excerpted from In Pursuit of Governance, autobiography of MDD Pieris)

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Editorial1 day ago

Editorial1 day agoCrime and cops

-

Editorial2 days ago

Editorial2 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSLT MOBITEL and Fintelex empower farmers with the launch of Yaya Agro App

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoOnline work compatibility of education tablets

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoHayleys Mobility unveils Premium Delivery Centre

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoNew policy framework for stock market deposits seen as a boon for companies