Features

Trust begets trust

by Usvatte-aratchi

The president’s rhetorical claims on Galle Face Green on February 4, 2023, amplified in Parliament on February 8 that there have been no dehydrating long queues at petrol stations and no protests by peasants demanding fertilizer because of good economic management since he assumed office hid from the public many facets of the slide down to that ‘stability’ at a low level. The economy is in some temporary and unstable hysteresis. The policy changes that brought it about were implemented well before the present president’s accession to office.

Let us look closer at what happened. The country went into default on its foreign debt in April 2022, four months before the new president took office. That action saved for other uses the foreign exchange that we would have paid in interest and capital to foreigners up to that point. That relieved pressure on the balance of payments. By implication, it also saved the value in rupees that would have been necessary to buy the foreign exchange to pay the debt owed to foreigners. That helped to relieve the pressure on the domestic budget. Those resources were released for other uses, contributing to that temporary relief.

What we can expect for the next two years and more is about the same level of resources augmented with the first tranche of the Extended Funds Facility, after the Fund and our government agree on terms. The president’s promise of higher pay for public servants later in the year is pie in the sky. Consequent upon the default on foreign debt payments and the perceived higher risks of lending to Sri Lanka, interest rates on borrowing from banks rose beyond 35 percent per annum. Few enterprises could function with funds borrowed at those rates of interest.

Banks loans, renewed year after year, are a common source of capital for enterprises in this country, in the absence of developed capital markets. The economy shrank in response to higher interest rates as the monetary multiplier became effective in its own time. Bad loan books in banks bloomed. Business activity slowed down and will shrink further. The policy decisions that brought about these changes were made before the present president took office. The recent fluctuation in the value of the rupee is a minor play in speculation. Like all bubbles of this sort in markets, it will break in its short time. Ignore the share market. It does not matter to the economy.

The ratio of imports to GDP, about 40 percent, is a fairly constant number in this economy. Selected imports were banned and the economy necessarily shrank, again. Crop failures called forth mainly out of ignorance and prejudice (with viyath maga [Wise Guys] as partners of government!), severely cut down the income of farmers and peasants and the results of that fall in income worked themselves throughout the economy Major policies and programmes that depressed total income and total demand that brought about the so-called stability antedated the advent of the new president. The central bank cannot raise the supply response as that response is governed by other stimuli: high risks of lending to a bankrupt nation.

In 2022, remittances from workers overseas rose in some degree, with the rise in the rupee value of the dollar. (Elementary, Dr. Watson.) There was some increase in tourism but far too small to compensate for losses in the economy elsewhere. Tourists came partly because foreign currency could buy a lot more after the May 2022 devaluation than before it. A room priced at $100 in 2021 (Rs 20,000) is now available for $ 75, (Rs26,3750), a lower price to the tourist and a higher price to the hotelier. Along with the shrinkage in the economy, the demand for energy fell. The ratio of energy use to GDP is (again) fairly constant. (The former Prime Minister of China, Li Keqiang, devised his own index number for the growth of GDP in China using the quantity of electricity consumed, freight carried and another as guides.)

The sale of petrol in 2022 fell by about 30 percent of its use in (say) 2018, the last year when the economy worked close to capacity. The demand for energy also fell more steeply consequent upon the sharply higher domestic prices, reflecting the higher prices of petroleum and related materials in international markets. (Both price and income effects were at play.) The fall in the quantity of petrol and other fuel sold in 2022 accounts for the disappearance of dehydrating queues in petrol stations. At my neighbourhood petrol station, I have not seen a line of cars waiting to fill up for many months.

Casual evidence of the fall in demand is the sparse traffic on roads even at times of congestion, evident earlier. There were four three-wheeler drivers who, for many years, operated from the top of our lane and there has been none from about mid-2021. The total effects of all this will be evident in the rate at which the economy shrank in 2022 when the figures will come out later this year. (That funny neologism NEGATIVE GROWTH is a challenge to make nonsense intelligible.) These adverse developments were consequent upon policy decisions made by the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government and inherited by the Wickremesinghe government.

This government reversed some stupid decisions by the former president, who single-handedly and ‘beyond the call of duty’ (as touted to boost his candidacy), destroyed the livelihoods in agriculture including fisheries on a massive scale. Peasants who cannot afford the new high prices for transport with a lower total income are mournfully protesting still, not on the Galle Face Green in Colombo but in rice fields, which ought to be luscious green mid-maha, now sickly brown affected by infection with insects, viruses and bacteria. Infested compost used in rice fields after the ban on the import of chemical fertilizer introduced substituting chemical fertilizer may have introduced pests to fields. The devastation of crops, both rice and corn, is rampant in Ampara, Polonnaruva, Anuradhapura and Kurunegala, all districts that contribute heavily to the marketable surplus of rice and provide feed to poultry farmers.

While the present policy regime is a distinct improvement on the inconsistencies, ignorance and stupidities of the preceding half-military regime, it (the present policy regime) contains standard prescriptions dictated for situations of economic austerity necessary to bring down the level of economic activity to what is affordable; affordable with low import capacity. Following the Hippocrates oath, the government, mercifully, has not harmed the economy in contrast to the earlier regime. The economy cannot work at higher capacity without hitting the ceiling of foreign exchange resources available. Go to Greece a decade back, Thailand 16 years back, and Korea several decades back. (I had written about the impending disasters in this newspaper and spoken about them in other fora for several years. Read a clear warning as early as 2013 in my address to the Annual Sessions of the Sri Lanka Economic Association.)

In no instance, that I cited, was there a surgeon present. But there is work for a team of surgeons and a whole lot of other medics in this instance. WHO will need to send plane loads of surgical supplies. A carbuncle with foul-smelling wounds spread all over this economy and the body politic now presents a serious risk of septicaemia (sepsis). The death rate from sepsis, is 50 percent, more or less, of those affected. Clean up the foul infection of corruption generated and spread by former presidents and their family members, hordes of members of parliament and local government bodies, gangs of government employees and armies of private citizens who helped to spread the bacteria. Some need to be made harmless and others quarantined long-term. The large crowds that throng to hear Anura Kumara Dissanayake, I reckon, are attracted by their persistent, substantiated and convincing promises to eliminate corruption in this society.

Fail in that and the JJB had better find places to hide in. The promises by the president of a bill that will be presented in Parliament to cure these ills in the future is neither here nor there. Every government that came to office after 1994 promised to kill the wild beast of an executive president who still rages savagely, unmolested. The present president who was a powerful figure in the Parliament 2015 -2020 did promise with great solemnity and even more bombastic celebration, that he would revise the constitution to deprive that office of the very powers that he now exploits. So will this bill against corruption be ‘Great Expectations’? To change the entire scene metaphorically, ‘Who is Sinhabahu enough ( ‘kuriru, darunu mee saturaa maranata) to slay this ferocious and woeful foe?’

The time to act is now. The elimination of this gangrene and septicaemia is essential for the revival of the economy. From casual observation, most people will not accept the sincerity of ‘unpopular policies and programmes’ that the president foretold until the general public trusts policymakers’ sincerity. The claims made by politicians of the government and some senior civil servants that there is no money to hold local government elections is another way of saying that among all the payments the government may make in the financial year 2023, holding elections has the lowest priority.

These claims and activities betray a deep-seated distrust of democratic ways of government. All people in democratic societies ought to protest at that ghastly assertion. Most people in our society will be further convinced that this government should not be trusted. Few things will restore trust in government as a frontal attack on corruption in the economy would. Government cannot carry through programmes that hurt the public in the short term without reviving the trust of the people in government which the government had lost much earlier. (I wrote about this in early 2020.) That restoration requires surgery to eliminate the foul and deathly carbuncle. (Recall the ‘restoration’ after (the Short (1640) and Long (1640-1660) Parliaments, the execution of Charles I of England in 1649 and the death of Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell in 1659. The English throne, from which Charles III reigns now, has never been vacant ever since.)

Features

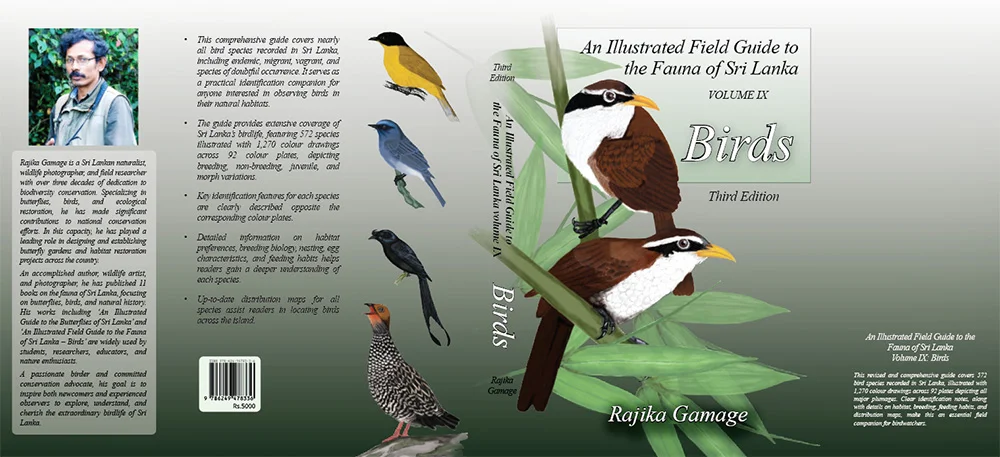

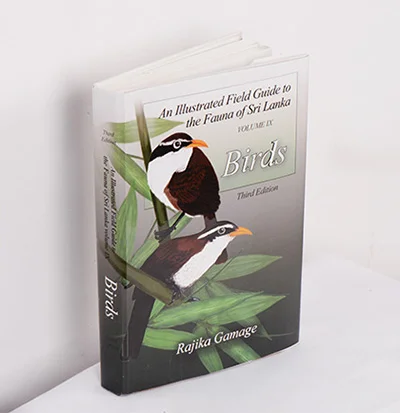

A life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

Sri Lanka wakes each morning to wings.

From the liquid whistle of a magpie robin in a garden hedge to the distant circling silhouette of an eagle above a forest canopy, birds define the rhythm of the island’s days.

Their colours ignite the imagination; their calls stir memory; their presence offers reassurance that nature still breathes alongside humanity. For conservation biologist Rajika Gamage, these winged lives are more than fleeting beauty—they are a lifelong calling.

Now, after years of patient observation, artistic collaboration, and scientific dedication, Gamage’s latest book, An Illustrated Field Guide to the Fauna of Sri Lanka – Birds, is set to reach readers when it hits the market on March 6.

The new edition promises to become one of the most comprehensive and visually rich bird guides ever produced for Sri Lanka.

Speaking to The Island, Gamage reflected on the inspiration behind his work and the enduring fascination birds hold for people across the country.

“Birds are an incredibly diverse group,” he said. “Their bright colours, distinct songs and calls, and showy displays contribute to their uniqueness, which is appreciated by all bird-loving individuals.”

Birds, he explained, occupy a special place in the natural world because they are among the most visible forms of wildlife. Unlike elusive mammals or secretive reptiles, birds share human spaces openly.

“Birds are widely distributed in all parts of the globe in large enough populations, making them the most common wildlife around human habitations,” Gamage said. “This offers a unique opportunity for observing and monitoring their diverse plumage and behaviours for conservation and recreational purposes.”

This accessibility has made birdwatching one of the most popular forms of wildlife observation in Sri Lanka, attracting everyone from seasoned scientists to curious schoolchildren.

A remarkable island of avian diversity

Despite its small size, Sri Lanka possesses extraordinary bird diversity.

According to Gamage, the country’s geographic position, varied climate, and diverse habitats—from coastal wetlands and rainforests to montane cloud forests and dry-zone scrublands—have created ideal conditions for birdlife.

“Sri Lanka is home to a rich diversity of birdlife, with a total of 522 bird species recorded in the country,” he said. “These species are spread across 23 orders, 89 families, and 267 genera.”

Of these, 478 species have been fully confirmed. Among them, 209 are breeding residents, meaning they live and reproduce on the island throughout the year.

Even more remarkable is Sri Lanka’s high level of endemism.

“Thirty-five of these breeding resident species are endemic to Sri Lanka,” Gamage noted. “They are confined entirely to the island, making them globally significant.”

These endemic species—from forest-dwelling flycatchers to vividly coloured barbets—represent evolutionary lineages shaped by Sri Lanka’s long geological isolation and ecological uniqueness.

In addition to resident birds, Sri Lanka also serves as a seasonal refuge for migratory species traveling thousands of kilometres.

“There are regular migrants that arrive annually, as well as irregular migrants that visit less predictably,” Gamage explained. “Vagrants, birds that appear outside their typical migratory routes, have also been spotted occasionally.”

Such unexpected visitors often generate excitement among birdwatchers and scientists alike, providing valuable insights into migration patterns and environmental change.

Rajika Gamage

A guide born from passion and necessity

The new field guide represents the culmination of years of research and builds upon Gamage’s earlier publication, which was released in 2017.

“The stimulus for this bird guide was due to the success of my first book,” he said. “This new edition aims to facilitate identification and provide an idea of what to look for in observed habitats or regions.”

The book is designed not merely as a scientific reference but as an accessible companion for anyone interested in birds. Its structure reflects this dual purpose.

“The first section is dedicated to the introduction, geography, and life history of Sri Lankan birds,” Gamage explained. “The second section is the main body of the guide, which illustrates 532 species of birds.”

Each illustration has been carefully crafted in colour to capture the distinctive plumage of each species.

“All illustrations are designed to show each bird’s significant and distinct plumage,” he said. “Where possible, the breeding, non-breeding, and juvenile plumages are provided.”

This attention to detail is especially important because many birds change appearance as they mature.

“Some groups, especially gulls, display many plumages between juveniles and adults,” Gamage noted. “Many take several years to develop full adult plumage and pass through semi-adult stages.”

By illustrating these stages, the guide helps birdwatchers avoid misidentification and deepen their understanding of avian development.

New discoveries and evolving science

One of the most exciting aspects of the new edition is its inclusion of newly recorded species and updated scientific classifications.

“Changes in the bird list of Sri Lanka, especially newly added endemic birds such as the Sri Lankan Shama, Sri Lanka Lesser Flameback, and Greater Flameback, are now included,” Gamage said.

Scientific names and classifications are not static; they evolve as researchers learn more about genetic relationships and species boundaries. The guide reflects these changes, ensuring it remains scientifically current.

The book also incorporates conservation status information based on the latest National Red Data Report and global assessments.

“The conservation status of Sri Lankan birds, as listed in the 2022 National Red Data Report and the global Red Data Report, are included,” Gamage said.

This information is vital for conservation planning and public awareness, highlighting which species face the greatest risk of extinction.

The guide also documents rare and accidental visitors, including species such as the Blue-and-white Flycatcher, Rufous-tailed Rock-thrush, and European Honey-buzzard.

“These represent accidental visitors and newly recorded vagrants,” Gamage said. “Altogether, the first edition offers some 25 additional species, all illustrated.”

Art and science in harmony

Unlike many field guides that rely heavily on photographs, Gamage’s book emphasises detailed illustrations. This choice reflects the unique advantages of scientific art.

Illustrations can emphasise diagnostic features, eliminate distracting backgrounds, and present birds in standardised poses, making identification easier.

“The principal birds on each page are painted to a standard scale,” Gamage explained. “Flight and behavioural sketches are shown at smaller scales.”

The guide also includes descriptions of habitats, distribution, nesting behaviour, and alternative names in English, Sinhala, and Tamil.

“The majority of birds have more than one English, Sinhala, and Tamil name,” he said. “All of these are included.”

This multilingual approach reflects Sri Lanka’s cultural diversity and ensures the guide is accessible to a wider audience.

A tool for conservation and connection

Beyond its scientific value, Gamage believes the book serves a deeper purpose: strengthening the bond between people and nature.

By helping readers identify birds and understand their lives, the guide fosters appreciation and responsibility.

“This field guide aims to facilitate identification and provide a general introduction to birds,” he said.

In an era of rapid environmental change, such knowledge is essential. Habitat loss, climate change, and human activity continue to threaten bird populations worldwide, including in Sri Lanka.

Yet birds also offer hope.

Their presence in gardens, wetlands, and forests reminds people of nature’s resilience—and their own role in protecting it.

Gamage hopes the guide will inspire both seasoned ornithologists and beginners alike.

“All these changes will make An Illustrated Field Guide to the Fauna of Sri Lanka – Birds one of the most comprehensive and accurate guides available within Sri Lanka,” he said.

A lifelong devotion takes flight

For Rajika Gamage, birds are not merely subjects of study—they are companions in a lifelong journey of discovery.

Each call heard at dawn, each silhouette glimpsed against the sky, each feathered visitor from distant lands reinforces the wonder that first drew him to ornithology.

With the release of his new book on March 6, that wonder will now be shared more widely than ever before.

In its pages, readers will find not only identification keys and scientific facts, but also something more enduring—the story of an island, told through wings, colour, and song.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Letting go: A Buddhist perspective

Buddhism, one of the world’s oldest religions, offers profound insights into the nature of existence and the ways we can alleviate our suffering. As one of the world’s most profound spiritual traditions, it offers a transformative solution: the art of letting go. Unlike simply losing interest in things or giving up, letting go in Buddhism is about liberation, releasing ourselves from the chain of attachment that prevents us from experiencing true peace and happiness. Letting go is a profound philosophical concept in Buddhism, deeply intertwined with an understanding of suffering, attachment, and the nature of reality. This philosophy encourages us to release our grip on desires, attachments, and on what we hold dear- whether relationships, material goods, or even their identities, ultimately leading to greater peace and enlightenment. Our tendency to cling tightly to the various aspects of life leads to a significant source of stress. We tend to grasp at things, perceiving them as solid and permanent, yet much of what we hold onto is transient and subject to change. This mistaken belief in permanence can trap us in cycles of worry, fear, and anxiety.

The challenge of letting go is especially evident during difficult periods in life. We may find ourselves ruminating over lost opportunities, failed relationships, and unmet expectations. Such thoughts can keep us ensnared in emotions like hurt, guilt, and shame, hindering our ability to move forward. By holding onto the past, we often prevent ourselves from embracing the present and future.

At the heart of Buddhist practice lies the concept of letting go, often encapsulated in the term “non-attachment.” Letting go is a crucial concept in both Buddhism and Christianity, emphasising the release of attachments that bind us and contribute to our suffering. At its core, letting go is about finding freedom from desires and acknowledging that both relationships and material possessions are fleeting and transient.

In Buddhism, letting go, or non-attachment, is fundamental for achieving inner peace. The First Noble Truth acknowledges that life is filled with suffering, often rooted in our cravings and attachment to things. The Second Noble Truth teaches that by letting go of this craving, we can transcend the cycles of life and attain enlightenment.

Spiritually, Buddhism emphasises the impermanence of all things (annica). We tend to cling to people, experiences, and even our identities, but everything is fleeting. Recogniing this helps us appreciate the present moment and fosters compassion. Instead of allowing attachments to cloud our relationships, letting go encourages us to engage with others without judgment or expectation, fostering deeper connections.

Philosophically, Buddhism challenges the notion of a permanent self (anatta) that is often the focus of human attachment. It teaches that our identity is not a fixed entity but a collection of experiences and perceptions in constant flux. Understanding this can help us see the futility of clinging to desires and identities, paving the way for a liberated state of being built on wisdom cultivated through meditation and mindfulness.

From a psychological standpoint, letting go can significantly improve our emotional health and well-being. Attachment often breeds fear, anxiety, and stress, while non-attachment promotes resilience and adaptability. When we embrace the idea of impermanence, we become more capable of handling life’s challenges without being overwhelmed. Mindfulness—being present and accepting our emotions without judgment—allows us to process difficult feelings constructively, making it easier to let go of what we cannot control.

Letting go is also an essential concept in Christianity, which emphasises surrender and trust in God. Biblical teachings encourage believers to let go of worries and anxieties, placing their faith in divine providence. For instance, verses like Matthew 6:34 remind individuals not to be anxious about tomorrow, but to focus on the present. By surrendering our burdens to God, we find peace and freedom from the weight of excessive attachment.

Moreover, both traditions highlight the importance of community. In Buddhism, the sangha, or community of practitioners, supports individuals on their journeys toward non-attachment. Similarly, the Christian community encourages believers to lean on one another for support, fostering a sense of belonging and shared faith that helps mitigate the loneliness that comes with attachment.

Ultimately, the concept of letting go serves as a powerful antidote to suffering in both Buddhism and Christianity. By embracing impermanence, cultivating wisdom, and practising mindfulness or faith, individuals can experience profound liberation. In our chaotic world, the principles of letting go offer a clear path toward inner peace, fulfilment, and deeper connections with ourselves, others, and the divine.

Buddhism explores the profound concept of letting go, providing valuable insights into the human experience and pathways to alleviating suffering. Rooted in one of the world’s oldest spiritual traditions, Buddhism presents letting go as a transformative practice, distinct from mere disengagement or giving up. Instead, it encompasses liberation from the chains of attachment that hinder us from experiencing genuine peace and happiness. Christianity too explore this profound concept in its teachings

At the core of Buddhist philosophy lies the idea of non-attachment, which encourages individuals to free themselves from desires and possessions, ultimately leading to tranquility and enlightenment. Letting go is intertwined with an understanding of suffering, attachment, and the transient nature of existence. This philosophy instructs us to relinquish our grip on what we hold dear—whether relationships, material goods, or even our identities—recognising that these are impermanent.

Buddhism’s First Noble Truth acknowledges that life inherently involves suffering, often stemming from our cravings and attachments. The Second Noble Truth reveals that overcoming this craving is key to transcending the cycles of life and achieving enlightenment. Emphasising the impermanence of all things, Buddhism invites us to appreciate the present moment and fosters compassion by helping us detach from fixed identities and experiences. This awareness enriches our relationships, allowing us to connect with others free from judgment or expectation.

Philosophically, Buddhism challenges the notion of a static self (anatta), asserting that our identity is not a fixed concept but rather a fluid collection of experiences. Recognising this notion helps highlight the futility of clinging to desires and identities, opening the door to a liberated existence founded on wisdom cultivated through meditation and mindfulness practices.

From a psychological perspective, the act of letting go can significantly enhance emotional health and well-being. Attachment often fuels fear, anxiety, and stress, while embracing non-attachment cultivates resilience and adaptability. By accepting impermanence, we equip ourselves to face life’s challenges with greater ease. Practicing mindfulness—being present and accepting emotions without judgment—further facilitates the process of releasing what is beyond our control.

In Christianity, the theme of letting go is also prominent, emphasizing surrender and trust in God. Scripture encourages believers to release their worries and anxieties by placing their faith in divine providence. For example, Matthew 6:34 advises individuals to focus on the present rather than fret over the future. By surrendering our burdens to God, we can experience relief from the weight of excessive attachment.

Both traditions underscore the significance of community in supporting the journey of letting go. In Buddhism, the sangha, or community of practitioners, encourages the pursuit of non-attachment. Likewise, Christian fellowship fosters belonging and shared faith, helping believers lean on one another for strength and mitigating the loneliness that can arise from attachment.

Ultimately, the concept of letting go serves as a powerful antidote to suffering in both Buddhism and Christianity. Embracing impermanence, nurturing wisdom, and practising mindfulness or trust can lead individuals toward profound liberation. In an increasingly chaotic world, the principles of letting go illuminate a pathway to inner peace, fulfilment, and deeper connections with ourselves, others, and the divine. By understanding and embodying this philosophy, we can navigate life’s complexities with grace and openness.////Buddhism delves into the profound concept of letting go, offering valuable insights into the human experience and pathways to alleviating suffering. As one of the world’s oldest spiritual traditions, Buddhism presents letting go as a transformative practice that goes beyond mere disengagement or resignation. It represents liberation from the chains of attachment that prevent us from experiencing true peace and happiness. Similarly, Christianity explores this profound concept in its teachings.

At the heart of Buddhist philosophy is the idea of non-attachment, which encourages individuals to free themselves from desires and possessions, ultimately leading to tranquility and enlightenment. Letting go is closely related to an understanding of suffering, attachment, and the impermanent nature of existence. This philosophy guides us to loosen our hold on what we cherish—be it relationships, material possessions, or even our own identities—recognizing that everything is transient. Through this understanding, we can cultivate a deeper sense of peace and fulfillment in our lives.

BY Dr. Justice Chandradasa Nanayakkara

BY Dr. Justice Chandradasa Nanayakkara

Features

Brilliant Navy officer no more

Rear Admiral Udaya Bandara, VSV, USP (retired)

This incident happened in 2006 when I was the Director Naval Operations, Special Forces and Maritime Surveillance under then Commander of the Navy Vice Admiral Wasantha Karannagoda. Udaya (fondly known as Bandi) was a trusted Naval Assistant (NA) to the Commander.

We were going through a very hard time fighting the LTTE Sea Tigers’ explosive-laden suicide boats that our Fast Attack Craft (s) and elite SBS’ Arrow Boats encountered in our littoral sea battles.

Brilliant Marine Engineer Commander (then) Chaminda Dissanayake, who was known for his “out of the box” thinking and superior technical skills on research and development, met me at my office at Naval Headquarters and showed me a blueprint of an explosive- laden remotely controlled small boat.

Udaya’s Naval Assistant’s office was next to mine, the Director Naval Operations office. Both places are very close to the Navy Commander’s office. I walked into Bandi’s office with Commander Dissa and showed this blueprint a brilliant idea. Being a Marine Engineer “par excellence”, Bandi immediately understood the great design. I urged him to brief the Commander of the Navy with Commander Dissa.

My burden was over! Bandi took over the project and within a few weeks we tested our first prototype “Explosive-laden Remotely Controlled arrow boat “at sea off Coral Cove in the Naval Base Trincomalee. It was a complete success.

This remotely controlled boats went out to sea with our SBS arrow boats fleet and had devastating effects against LTTE suicide boats and their small boats fleet. Thanks, Bandi, for your contribution. The present-day Admiral of the Fleet used to tell us during those days “you cannot buy a Navy – you have to build one”!

We built our own small boats squadrons at our boat yards in Welisara and Trincomalee to bring LTTE Sea Tigers. The Special Boats Squadron (SBS) and rapid action boats squadron (RABS) being so useful with remotely controlled explosive-laden arrow boats to win sea battles convincingly.

Bandi used to say, “Navy is a technical service and we should give ALL SRI LANKA NAVY OFFICERS FIRST A TECHNICAL DEGREE AT OUR ACADEMY (BTec degree).” That idea did not receive much attention here, but the Indian Navy—Bandi graduated as a Marine Engineer- at Indian Navy Engineering College SLNS Shivaji in Lonavala, Pune, India— understood this idea well over two decades ago. Indian Navy Commissioned their new Naval Academy at Ezhimala (in Kerala State) which is the largest Naval Academy in Asia (Campus covers area of 2,452 acres) starts its Naval officers training with a BTech degree, regardless of what branch of the navy one joined.

Bandi’s technical expertise was not limited to SLN. He was the pioneer of “Mini – Hydro Power projects” in Sri Lanka. When I was a young officer, he urged me to invest some money in one of these projects and advised me “Sir! as long as water flows through turbines, you will get money from the CEB, which is always short of electricity”. I regret that I did not heed Bandi’s advice.

When he worked under me when I was Commander Southern Naval Area, as my senior Technical Officer, I observed pencil marks on walls of his chalet and I inquired from him what they were. He said it was the result of his “pencil shooting training”, a drill Practical Pistol Firers do to improve their skills. He used to practice “draw and fire” drills and pencil shooting drills late into nights to be a good Practical Pistol firer in Sri Lanka Navy team. He didn’t stop at that. He represented Sri Lanka National Practical Pistol Firing team and won International Championships.

As the Officer in charge of Technical Training in the Navy, he worked as Training Commander to train Royal Oman Navy Engineering Artificers in Sri Lanka, especially on Fast Attack Craft Main Engine Overhauls. The Royal Oman Navy Commander was so impressed with the knowledge acquired by Artificers that he donated money for the construction of a four-storey accommodation building for Sri Lanka Navy Naval and Maritime Academy, Trincomalee now known as “Oman Building”. The credit for this project should go to Bandi.

Bandi’s wife was a senior Judge of Kegalle High Court, and she retired a few years ago. Their only child, a son studied at the British School, Colombo and followed in his mother’s footsteps became a lawyer. Bandi was so much attached to his family and very proud of his son’s accomplishments.

When Bandi was due to retire in 2016 as a Rear Admiral and Director General Training, after distinguished service of 34 years, and reaching retirement age of 55 years, I requested him to serve for some more years after mobilising him into our Naval Reserve Force. He had other plans. He wanted to take his mini-Hydro Power projects to East African countries.

His demise after a very brief illness at age of 64 years was a shock to his family and friends. His funeral was held on Feb. 27 with Full Military Honors befitting a Rear Admiral at his home town Aranayake.

Dear Bandi, the beautiful Sri Lanka Navy, Naval and Maritime Academy in Trincomalee, which was built with your efforts will serve for Sri Lanka Navy Officer Trainees and sailors for a very long time and remember you forever.

May dear Bandi attain the supreme bliss of Nirvana!

Naval and Maritime Academy, Trincomalee

By Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc

(Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defence Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd,

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation,

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoFuture must be won

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoCEA halts development at Mandativu grounds until EIA completion