Life style

Time to end Santa’s ‘naughty list’?

Many of us have magical memories of Santa secretly bringing gifts and joy to our childhood homes – but is there a darker side to the beloved Christmas tradition?

“You better watch out, you better not cry, you better not pout, I’m telling you why, Santa Claus is coming to town.”

And don’t I know it! This is the first year that my three-year-old daughter has fully immersed herself in the mythology of Santa. As she tells me just how Old Saint Nick is going to fit down our chimney, I can see a glint of pure wonder in her eyes that immediately transports me back to my own childhood Christmases.

I was – and I’m happy to admit it – a full-blown believer. I absolutely loved the magic of Christmas, especially Santa Claus, and my parents went, let’s say, above and beyond to encourage it. On Christmas morning I would tiptoe downstairs to find the fireguard ajar, the remnants of a hurriedly-eaten mince pie on a plate, a reindeer-chewed carrot and a tissue with a red smudge where Santa had clearly polished Rudolph’s nose (definitely not my Mum’s lipstick). The evidence was, as far as I was concerned, insurmountable.

However, as I begin to construct my own Santa Claus myth for my daughter I can’t help but feel pangs of guilt. Could fuelling her belief in all this festive magic in some way undermine her trust? In moments of exasperation, I can hear myself invoke the threat of the “naughty list” and I see a sudden flash of fear across her face. It’s made me wonder what kind of Santa I want to create for my daughter and, to be honest, whether I should be doing it at all.

Fascinatingly, although the modern world feels like it has been stripped of so much of its magic, belief in Santa Claus has remained remarkably consistent. Back in 1978, a study published in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry found that 85% of four-year-olds said they believed in Santa. More than a quarter of a century later, in 2011, research published in the Journal of Cognition and Development found that a very similar 83% of 5-year-olds claimed to be true believers. And that is despite Google Trends showing that the search term “is Santa real” spikes every December.

I guess it’s not all that surprising. The cultural evidence we create as a society for the existence of Santa certainly stacks up. He features in every Christmas TV show and movie, he’s camped out in strange little sheds in every shopping centre we visit. Each year the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD) allows you to track Santa’s journey on Christmas Eve. To reassure children during the pandemic in 2020, the World Health Organisation issued a tongue-in-cheek statement declaring that Santa was “immune” from Covid 19. To be honest, there’s more evidence for Santa’s existence out there than my own, which is almost enough to trigger a mild existential crisis.

And it’s precisely this effort on behalf of parents, and society in general, to create such seemingly overwhelming evidence for the existence of Santa Claus that David Kyle Johnson, a professor of philosophy at King’s College in Pennsylvania, describes as “The Santa Lie” in his book The Myths That Stole Christmas.

“When I say ‘The Santa Lie’, I am not referring to the entire mythos of Santa Claus, I am referring to a particular practice within that myth: Parents tricking their children into believing that Santa Claus is literally real,” says Johnson. He highlights how we don’t simply ask children to imagine Santa, but rather to actually believe in him. It’s this emphasis on belief over imagination that Johnson sees as harmful.

“I definitely think it can erode trust between a parent and a child, but I think the biggest danger is the anti-critical thinking lessons that they are teaching,” says Johnson. “Parents who are especially dedicated to ‘The Santa Lie’ will perform feats of insanity to ensure their children keep believing.”

This brings a flash back to my childhood, where at eight-years-old I wrote a letter to Santa probing the logistics of his yearly mission, only for my Dad to write back in his best “olden times” handwriting, covering the reply in sooty fingerprints (probably whilst gnawing on a raw carrot). My colleague Rob shared that his Mum apparently found the carrot a particularly disgusting part of the Christmas Eve ritual.

For Johnson, it is this creation of false evidence and convincing kids that bad evidence is in fact good evidence that undermines the kind of critical thinking we should be encouraging in children in this era of fake news, conspiracy theories and science denial. “The ‘Santa lie’ is part of a parenting practice that encourages people to believe what they want to believe, simply because of the psychological reward,” says Johnson. “That’s really bad for society in general.”

When magic is no longer the answer, children start to gather evidence – Cyndy Scheibe

Interestingly, there are some experts, however, who argue that believing in Santa Claus can actually encourage critical thinking in children. It hinges on how parents support them in the process of eventually discovering and accepting the truth. Cyndy Scheibe, professor of psychology at Ithaca College in New York, and an expert in media literacy, has been researching children’s belief in Santa Claus since the 1980s. She has conducted research in three different time periods and found surprisingly consistent results each time.

“Kids start to ask questions around four or five, and then really start to have doubts around the age of six,” says Scheibe. Each time she conducted her research Schiebe found the same thing, that the average age children stop believing in Santa was between seven and eight. However, it is very rarely a sudden thing. “I found that that process seemed to take about two years for kids to navigate through.”

Scheibe explains that this transition period, of between seven and nine years old, makes sense because it aligns with the ages when children go from being so-called “pre-operational thinkers” to “concrete operational thinkers”. Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget developed these terms to explain how children gradually build up their understanding and knowledge of the world. At the pre-operational stage, a child’s idea of the world is mainly shaped by how things appear, rather than by deeper logical reasoning. But that changes as children begin to probe and question the things they see or hear. “A concrete operational thinker wants evidence,” Scheibe says. “They begin to mature cognitively, where the story doesn’t make logical sense and magic is no longer the answer. Then they start to gather evidence.”

And it is at this stage that Scheibe says parents need to be led by their children, in order to help them develop their critical thinking skills. “They function as little scientists, testing out hypotheses and gathering data to figure out what’s true and what’s not,” Schiebe says. This is something parents can encourage through asking careful questions. “In media literacy it’s all about asking questions. What do you think? How could we really find out? Why do you think people do that?” Scheibe explains.

My colleague Amy told me about the evidence that triggered the end of her belief in Santa Claus when she was around seven: “I recognised my mum’s handwriting on the label and was totally shocked!”. However, Amy said she doesn’t remember feeling hurt or betrayed by the discovery. Rather, “it made me feel like a grown-up and that I understood something about the world”.

Amy’s experience tallies with research published in Child Psychology and Human Development that found children generally discovered the truth about Santa on their own at the age of seven and reported “predominantly positive” reactions to discovering this. However, the study showed parents, on the other hand, fared less well, describing themselves as “predominantly sad” in reaction to their child’s discovery.

And herein lies the major issue for both Johnson and Schiebe: It’s not so much children but rather their parents who refuse to let go of Santa Claus.

Schiebe describes how throughout her decades of research the only times she saw belief in Santa become “problematic” was when parents continued to perpetuate the belief beyond the time the child was ready for the truth. “I think that one problem is kids are ready to hear the truth, but you’re not ready to let go of the truth, and you’ve got to let go of the truth,” Scheibe says.

As a father I can understand the draw of keeping hold of the Santa mythology for as long as possible. On the one hand it feels like it’s a way of stopping them growing up too fast, of protecting an element of their innocence somehow. On the other hand, Santa has, for many parents – and I include myself in this – become a quick-fix for managing behaviour with his infamous “naughty list”.

The idea that Santa is watching all of the time can be quite a frightening concept for children – Rachel Andrew

It’s always been the part of the Santa Claus myth that I have found the most uncomfortable. His presence as a sort of festive Big Brother, an all-seeing eye constantly judging your behaviour as either “naughty” or “nice”. And recently this element of the mythos has gained a whole new lease of life, with Elf on the Shelf – described on its own website as “Santa’s scout elf” – supposedly reporting behaviour back to Santa, and even fake CCTV “Santa cams” that parents can install to hammer home the message that you are never not being watched. In many ways it feels Santa has become a working model for Foucault’s panopticism – a form of internalised surveillance and self-monitoring that no longer requires external enforcement.

“For a lot of children Santa can be quite a scary figure. That idea that he is watching all of the time can be quite a frightening concept,” says Rachel Andrew, a clinical psychologist specialising in child and family psychology. Andrew believes using Santa’s “naughty list” as a behaviour management tool is flawed in numerous ways. “Having children believe they are on an imaginary naughty list for behaviour they have done over, what, an entire year? Three or four months? It’s so far against what we know is likely to encourage positive behaviour in our children,” Andrew says.

For Andrew, the way parents use Santa for discipline is too vague for children to really understand what we are asking of them, and the time frames are often so broad it is unattainable.

“One of the issues might be that the discipline is not coming from you as a parent. You’re giving it away to somebody who is outside of your own family home,” says Andrew. This can open up the potential that your child doesn’t see you as the person they need to change or monitor their behaviour for. Also, Andrew sees the age-old threat of Santa not delivering toys to naughty children as realistically unenforceable. “It’s not proportionate to any behaviour that a child is going to do, that they might lose all their Christmas gifts. And I haven’t met a child yet who’s not had any gifts due to their behaviour. It’s unlikely any parent is going to follow it through, so it is also an empty threat.”

There’s another uncomfortable by-product of Santa making a list and checking it twice to find out who’s been naughty or nice: it builds an idea that gifts are a measurement of their moral worth.

“We have so many ways that we perpetuate the idea that people get what they deserve,” says Philip N Cohen, professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park. “You’re telling [children] that the presents they get are a function of the quality of their goodness, which just seems a harsh lesson in a world with so much inequality.”

Cohen wonders what happens when children’s belief in Santa intersects with their increasing awareness of the inequality around them, especially at an age when they may be looking for explanations for that inequality. “Do you have seven-year-old kids who can see inequality all around them who still believe that Santa gives you presents based on your moral worth?” Cohen asks. “That would be teaching well-off children that they’re getting what they deserve, because they’re good, and the poor children are getting what they deserve, because they’re not good. That just seems like a corrosive lesson for them.”

As the cost of living crisis bites this Christmas, this feels a more relevant issue than ever. Scheibe believes that one way to combat this is to share out Santa’s gift giving responsibilities. “There are some families in which all the gifts come from Santa. Personally I think that’s a mistake,” Scheibe says. She argues that children should be more involved in the process of gift giving at Christmas. “Have Santa Claus be a piece, but also it’s about more than that, it’s about giving and receiving and you can get kids involved in that pretty early.”

So, as my daughter sits down to watch another episode of The Santa Clauses, what kind of Santa is it that I want to create for her?

I think I definitely want to be careful that I don’t try to stray too far from playful imagination into literal belief. I certainly want to burn the “naughty list” – I’d like her Santa to be more Gandalf, less all-seeing Eye of Sauron. And as she gets older I hope I am prepared to let go of the truth when she is ready for me to, and to encourage her in that journey of discovery. Although I don’t believe that means letting Santa go, but rather just initiating a new Santa to the club.

A perfect example of this is what Schiebe told me happened when her own daughter stopped believing: “I said: ‘So now that you know the truth, you get to be Santa Claus, and you know what that means? You can get up in the middle of the night put things in people’s stockings, but you’ve got to make sure nobody sees you, and it’s got to be something you know they want. So then, the next Christmas morning, when I woke up, there were things in my stocking that I hadn’t gotten. The look on her face of how excited she was that she had been able to be Santa Claus, that was just spectacular.”

(Guardian)

Life style

Sri Lanka’s first elephant orphanage celebrates 50 years

By Amal Jayasinghe

Pics by Ishara Kodikara

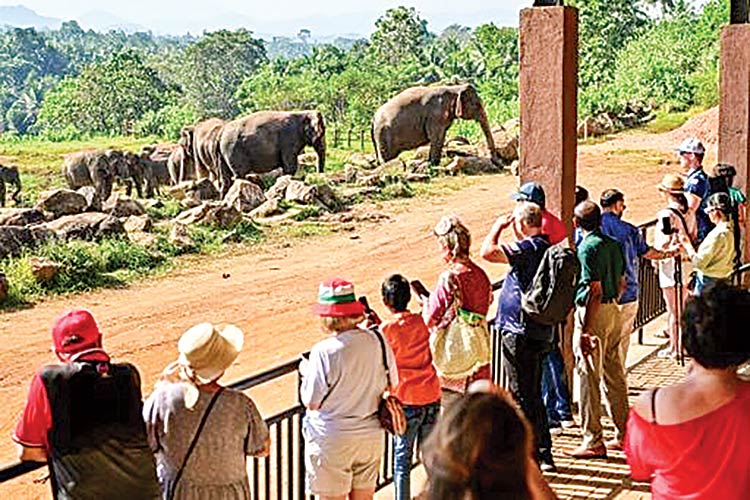

Sri Lanka’s main elephant orphanage marked its 50th anniversary on Sunday february 16 with a fruit feast for the 68 jumbos at the showpiece centre, reputedly the world’s first care home for destitute pachyderms. The Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage lavished pineapples, bananas, melons and cucumbers on its residents to celebrate the anniversary of their home, which is a major tourist attraction.

A few officials and tourists invited to the low-key celebration were served milk rice and traditional sweets while four generations of elephants born in captivity frolicked in the nearby Maha Oya river.

“The first birth at this orphanage was in 1984, and since then, there have been a total of 76,” said chief curator Sanjaya Ratnayake, as the elephants returned from their daily river bath.

“This has been a successful breeding programme, and today we have four generations of elephants here, with the youngest 18 months old and the oldest 70 years,” he told AFP.

The orphanage recorded its first twin birth in August 2021 — a rarity among Asian elephants — and both calves are doing well.

Two years before the orphanage was formally established as a government institution in February 1975, five orphaned elephants were cared for at a smaller facility in the southern resort town of Bentota.

“Since the orphanage was set up at Pinnawala in 1975, in a coconut grove, the animals have had more space to roam, with good weather and plenty of food available in the surrounding area,” Ratnayake said.

The home requires 14,500 kilos of coconut and palm tree leaves, along with other foliage, to satisfy the elephants’ voracious appetites.

It also buys tonnes of fruit and milk for the younger calves, who are adored by the foreign and local visitors to the orphanage, located about 90 kilometres (56 miles) east of the capital Colombo.

It is also a major revenue generator for the state, earning millions of dollars a year in entrance fees. Visitors can watch the elephants from a distance or get up close and help scrub them during bath times.

– Tragic toll –

The facility lacked running water and electricity at its inception but things improved as it gained international fame in subsequent years, said retired senior mahout K.G. Sumanabanda, 65.

“I was also fortunate to be present when we had the first birth in captivity,” Sumanabanda told AFP, visiting the home for the jubilee celebrations.

During his career spanning over three decades as a traditional elephant keeper, he trained more than 60 other mahouts and is still consulted by temples and individuals who own domesticated elephants.

Twenty years ago, Sri Lankan authorities opened another elephant home south of the island to care for orphaned, abandoned or injured elephants and later return them back to the wild.

While Pinnawala is seen by many as a success, Sri Lanka is also facing a major human-elephant conflict in areas bordering traditional wildlife sanctuaries.

Elephants return to Sri Lanka’s Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage after taking their daily bath in a river

Deputy Minister of Environment Anton Jayakody told AFP on Sunday that 450 elephants and 150 people were killed in clashes in 2023, continuing an alarming trend of fatalities in the human-elephant conflict. The previous year saw 433 elephants and 145 people were killed.

Killing or harming elephants is a criminal offence in Sri Lanka, which has an estimated 7,000 wild elephants and where jumbos are considered a national treasure, partly due to their significance in Buddhist culture.

But the massacre continues as desperate farmers face the brunt of elephants raiding their crops and destroying livelihoods.

The minister was confident the new government could tackle the problem by preventing elephants from crossing into villages.

“We are planning to introduce multiple barriers—these may include electric fences, trenches, or other deterrents—to make it more difficult for wild elephants to stray into villages,” Jayakody told AFP.

Life style

Growing the Cultural Landscape with Suhanya Raffel

The Geoffrey Bawa Trust which was launched its 2025 is followed by Curatorial Conversations Series. Recently a presentation was made S by M+ Museum director and Geoffrey Bawa Trustee Suhanya Raffel. Speaking at the new Bawa Space on Horton Place, Raffel drew on extensive experience in the museum and art world to present insights and programming from the M+ Museum in Hong Kong. M+ is Asia’s first global museum of contemporary visual culture and presents itself as an intersection of visual art, design and architecture, and the moving image.

The evening presented an opportunity to hear from a leading expert in the museum field and discuss Sri Lanka’s present and future cultural landscape. It also highlighted the role of the Geoffrey Bawa Trust in conserving the legacy of the architect and his collaborators, and promoting contemporary art and design. “There are amazing artists, great designers, and reactive minds in Sri Lanka and the region,” Raffel said at a press event earlier in the afternoon. “There is opportunity in the aspiration to establish things, artists doing very important work, and the energy of individuals to try to make a difference.”

In part, this opportunity stems from the lack of established large-scale infrastructure to conserve Sri Lanka’s modern cultural legacy and support emerging artists. While there is the scope to shape the domestic art world and build institutions reflective of the local cultural community, there are also limitations and challenges in realising this potential.

Raffel spoke extensively about the need to build curatorial skills and knowledge and nurture cultural leaders in the region. Recognising this need, the Geoffrey Bawa Trust maintains public programmes, including exhibitions, residencies, tours, and lectures, to broaden public discourse and knowledge on the built environment and the arts in Sri Lanka and overseas. To fulfil curatorial needs and encourage growth in artistic and cultural institutions such as museums, the Trust employs a dedicated curatorial team and runs a robust internship and training programme. It is hoped that building this skill base will encourage others to explore similar career opportunities and support art, design, and architecture in the region. Sri Lankan visual arts over the past century have enjoyed wide international acclaim. “Sri Lanka is known globally for its creative work,” says Raffel, “it is culturally very strong.”

Geoffrey Bawa is a great example of this global influence. During his lifetime, the architect was very well-known in Sri Lanka and among contemporaries around the world. His structural, landscape, and furniture designs continue to guide and inspire. “It is very important for makers to be seen with their international peers,” Raffel explains. This cultural engagement on regional and international platforms is paramount for ensuring open dialogue and exchange. This means supporting collaborations, encouraging foreign markers to come to Sri Lanka, and exhibiting Sri Lankan work internationally.

The Trust is working to support this global dialogue by hosting installations by artists and makers from Sri Lanka and abroad, as was done in celebration of Geoffrey Bawa’s 100th birthday and again throughout the To Lunuganga programme from 2023-2024. The Trust took Geoffrey Bawa’s work to the world in 2024 with the travelling It is Essential to be There exhibition in Sri Lanka, India, and the United States.

The Trust is proud to be part of major professional international forums such as the International Confederation of Architectural Museums and the Committee for Modern and Contemporary Art Museums, both affiliated with the International Council of Museums. These platforms are vital for global knowledge sharing and advocacy. “We want more of these types of collaborations to happen both with the Geoffrey Bawa Trust, but also other arts and cultural institutions in Sri Lanka,” says Raffel.

In furthering this mission, the Trust is excited to present the new Bawa Space as the organisation’s public face and offer opportunities for the public to engage with the Trust’s work. Located in a recently restored Bawa-designed house from 1959, the Bawa Space doubles as the Geoffrey Bawa Trust headquarters and archives, as well as a new gallery and space for talks and events that will continue year-round.

Life style

Colombo Fashion Week 19-22 February: Two decades of creating the Fashion Eco-system in Sri Lanka

This year CFW will showcase a selection of Emerging Designers alongside established Sri Lankan designers. Adding international flavour will be well known designers from India Suket Dhir, Urvashi Kaur and Zaheer Abbas from Pakistan.

Colombo Fashion Week (CFW), presented by Mastercard, enters its 22nd year in 2025 with its Summer edition, marking another milestone in its journey as one of the four fashion weeks in Asia that have surpassed 2o years.Emerging Designer initiative of CFW this time remains one of its main pillars, providing an entry point for the next generation to pursue design-based entrepreneurship. This in line with the introduction of the Craft Fashion Fund this year is a testament to this commitment. The Craft Fashion Fund will select two winners, one who incorporates batik and another who utilizes crafts other than batik. This initiative passed 20 years.

Over the years, CFW has proven to be the backbone of Sri Lanka’s fashion design industry—its only voice—while creating a fashion ecosystem that provides support to new emerging designers entering the industry. Informally known as South Asian Fashion Week, it serves as a regional hub due to its geopolitical advantage. It is also one of the most significant fashion weeks in South Asia, having played a crucial role in revitalizing the country’s fashion design industry.

This year, Colombo Fashion Week has also expanded its international footprint since joining as a founding member of the newly created BRICS International Fashion Federation. This aligns with CFW’s ongoing mission to bridge diverse fashion markets and foster creative dialogue across continents. As part of this federation, CFW has signed a designer exchange program with BRICS, where a designer from a BRICS country will showcase their work at CFW, and a Sri Lankan designer will present their collection there. CFW continues to play a pivotal role in presenting Sri Lanka through the lenses of arts, culture, and sustainability, further contributing to destination marketing on a global scale.

The Head Table From L to R: Harsha Maduranga, GM – Vision Care, Yatila Wijemanne, Chairman – Juniper, Dr. Vibash Wijeratne, Dirand CEO – Ninewells, Shamara Silva, Mrkt & Media Dir – Unilever, Ruwan Perera, CEO – NDB Wealth, Kamal Munasinghe, Area VP and GM – Cinnamon Grand, Ajai Vir Singh, Founder – CFW, Sandun Hapugoda, Country Mgr – Mastercard, Samrat Datta, GM – Taj Samudra, Bernhard Stefan, MD – Nestlé Lanka, Ramani Fernando, Founder – RF Salons, Arjuna Kumarasinghe, MD -Cargills Food & Beverages

Ajai Vir Singh, Founder, Colombo Fashion Week stated: “Colombo Fashion Week has consistently demonstrated its commitment to developing Sri Lanka’s fashion industry through strategic international partnerships and innovative platforms. Our growing international recognition and expanding designer network reflects vital role this platform plays in positioning Sri Lanka through its creative industries.”

Mastercard, as the presenting partner, continues to champion CFW’s vision of sustainable and inclusive fashion innovation, focusing on digitizing sustainability initiatives and supporting small and medium fashion enterprises.

Sandun Hapugoda, Country Manager, Sri Lanka & Maldives, highlights: “Mastercard is thrilled to partner with Colombo Fashion Week once again, celebrating the incredible talent and creativity within the fashion industry. This partnership aligns perfectly with our commitment to support local artistry. Together, we aim to inspire new possibilities, connect communities, support sustainable fashion initiatives, and elevate the local fashion industry to a global audience, delivering a truly priceless experience. We also anticipate CFW to be a great support to boost the Sri Lanka tourism industry as well.”

The Craft Fashion Fund encourages young designers to engage with and incorporate Sri Lankan crafts into their collections. This approach has been highly successful for designers in other South Asian countries, where traditional crafts have helped establish a unique identity for them. Sri Lankan fashion has its best opportunity to develop a distinct identity when designers integrate local crafts into their work. The developing of this identity has been professed by CFW among the design fraternity, so they are able to create market demand beyond Sri Lanka.

The Emerging Designer initiative of CFW remains one of its main pillars, providing an entry point for the next generation to pursue design-based entrepreneurship. This in line with the introduction of the Craft Fashion Fund this year is a testament to this commitment. The Craft Fashion Fund will select two winners, one who incorporates batik and another who utilizes crafts other than batik. This initiative will support two exceptional designers, ensuring the preservation and evolution of Sri Lanka’s rich artistic heritage. This season, fifteen emerging designers will present their collections, further demonstrating CFW’s dedication to fostering the next generation of fashion talent.

Fazeena Majeed Rajabdeen, Director & CEO, Colombo Fashion Week further added: “Colombo Fashion Week, with its focus on nurturing new talent and emerging designers, has played a pivotal role in reviving and propelling Sri Lanka’s fashion industry. We are proud to present 15 emerging designers this year and to have Sharmila Ruberu mentoring these designers on collection planning. This, along with the Craft Fashion Fund, reiterates our commitment to further the thriving ecosystem we have built, embracing sustainability and empowering young talent.”

Colombo Fashion Week Summer 2025 is set to transform Colombo into an immersive fashion destination by showcasing designers across three of the city’s most prestigious locations. The key partners of Destination Colombo includes Shangri-La, Taj Samudra, and Cinnamon Grand. The shows will feature an impressive roster of international and local talent, including designers from India, Italy and Russia. Renowned creators such as Rimzim Dadu,

Cettina Bucca, Suneet Varma and JJ Valaya, will present alongside celebrated Sri Lankan designers including Fouzul Hameed, Sonali Dharmawardena, Asanka De Mel, Aslam Hussein, Kamil Hewawitharana, Dimuthu Sahabandu, Indi Yapa Abeywardena and Charini Suriyage.

Colombo Fashion Week 2025 is proudly supported by Mastercard, presenting partner along with Shangri-La, Cinnamon Grand, Taj Samudra, NDB Wealth, Yatra, Ninewells Aesthetic Centre, Tresemme, Vaseline, Juniper, Chupa Chups, Nestle-Nescafe, Vision Care, Knuckles, Hameedia, Ramani Fernando, Wijeya Newspapers, Hard Talk, Acorn and Emerging Media.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCommercial High Court orders AASSL to pay Rs 176 mn for unilateral termination of contract

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoSri Lanka face Australia in Masters World Cup semi-final today

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoUSAID and NGOS under siege

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDoing it in the Philippines…

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoImpact of US policy shift on Sri Lanka

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCourtroom shooting: Police admit serious security lapses

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog delivers strong FY 2024 performance with 10% Core Revenue Growth

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoFSP lambasts Budget as extension of IMF austerity agenda at the expense of people