Features

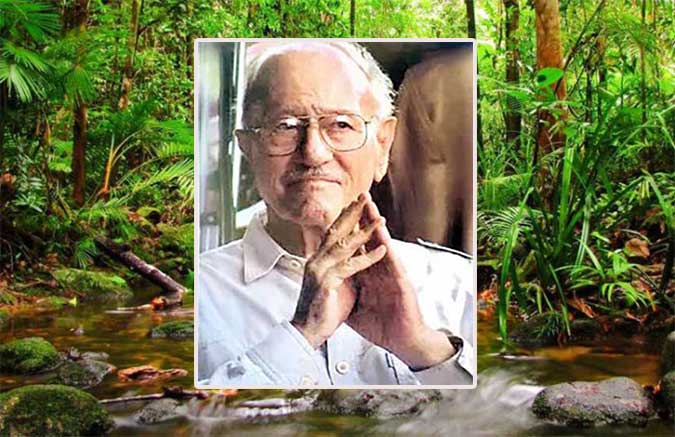

Thilo Hoffman’s odyssey in then Ceylon

Excerpted from the Authorized biography

by Douglas B. Ranasinghe

(Continued from Jan. 22)

Thilo Walter Hoffmann was born on March 13, 1922 at St Gallen in Switzerland. He was the eldest child of Walter Hoffmann, a paediatrician, and his wife Gertrud, nee Bopp. Walter’s father was a proprietary farmer, and Gertrud’s father, too, was a doctor. Thilo’s mother and both grandmothers were housewives, as was then the norm.

Dr Hoffmann was well known in that part of the country as a leading specialist in his field, and widely liked. He also wrote and published numerous articles on medical, dietary and educational subjects. Beyond his regular work, he dedicated much of his life to a cause. Every day for nearly forty years he voluntarily spent two to three hours in a children’s institution. Here, without expecting or receiving a cent, he treated thousands of newborn infants and small children.

Thilo had two sisters and a brother seven years younger. They grew up in St Gallen, about 700 metres above sea level, in the north-east of the country, close to Lake Constance and to the German and Austrian borders.

Walter was a keen botanist and a skilled mountaineer. He took Thilo along on walks and journeys from an early age, and introduced him to the wonders and secrets of nature. Before entering school at the age of six, Thilo knew the names of many plants and animals. It is no surprise that interest in nature became a hobby with him. But who would have thought that this would lead him to play an historic role in the protection of the flora and fauna of a distant tropical island?

Thilo led a life normal for a boy of his background. Like all Swiss children, he was sent to State schools for his primary, secondary and higher education. He was a Boy Scout. The sport he liked best was skiing, when the nearby hills and mountains were covered with snow.

At 18-years he took his matriculation examination, and entered the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, a world-renowned university where several Nobel laureates, including Albert Einstein, have studied or taught. Thilo Hoffmann followed a course in Agronomy, and finished with a Master’s Degree in Agricultural Science.

A happy time of youth was interrupted by the Second World War, which broke out in neighbouring Germany. Thilo was then still studying. Food, clothing and energy were severely rationed, traveling was restricted, and austerity prevailed all round. It was impossible to leave little Switzerland for nearly five years, an important period in his life. Like all young citizens, he had to join its militia army and take the 17-week basic training course.

To Ceylon

In 1946, just after the war, a Swiss agricultural firm in Ceylon needed a Scientific Advisor, and inquired from Thilo’s university. They recommended the new 24-year-old graduate. By now he had developed “a romantic yearning for the wide world, in particular for the tropics”. But he hesitated because his mother was unhappy about the separation. When he consented five other candidates had been listed, but the head of the firm, A. Baur, selected him.

Amidst the travel constraints, Thilo left Switzerland by train for the seaport of Marseilles, in the south of France. He boarded a British vessel, Durban Castle, then a troop ship, which would take him to Port Said in Egypt. Here he had to remain for three weeks until another ship was found for the rest of the voyage. Thilo liked that country, and was later to return to it on a number of occasions, on business and as a tourist.

From Egypt, he travelled in the US Liberty vessel Black Warrior, a cargo boat, which stopped at three ports and took two months to reach Colombo. The passage through the Suez Canal was an adventure. Convoys from north and south crossed within it on the Great Bitter Lake, where war-damaged and sunken ships were lying.

For the first time Thilo saw the desert, stretching away on either side of the canal. Beyond, on the Red Sea, the ship stayed two weeks at Jeddah, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in heat he found almost unbearable – there was no air conditioning then. After a brief stop at Aden, three weeks were spent at Bombay, where unloading and loading were slowed by the nightly curfew due to the Hindu-Muslim riots which convulsed India at that time.

Eventually, on an early morning in October, the ship anchored mid-harbour at Colombo. Travellers then landed at the passenger jetty by rowing boat or launch. There was a little episode. The Managing Director of Baurs came on board for Thilo, accompanied by a junior assistant. But Thilo was not ready. He is a “bad sailor,” feels unwell on board, and was unable to pack and prepare to disembark as long as the ship was still moving.

The big boss did not take kindly to what he perceived to be lack of respect, and stormed off the ship. The assistant was sent back two hours later, to escort the new arrival ashore and help with Customs formalities. It was not exactly the auspicious beginning of a promising career.

Employment

The first Swiss firm to trade in the East was Volkarts, which exchanged manufactured goods from Europe for raw materials from India such as cotton and jute. In 1857 it opened an office in Colombo, and exported coffee, coconut oil and cinnamon from Ceylon.

Alfred Baur was born in a village in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. He arrived in Ceylon when he was 19 as an Assistant at Volkarts. A dynamic person, six years later he was a proprietary planter at Rajakadaluwa a few miles north of Chilaw – an area then well known for elephant, bear and leopard.

In 1897 at the age of 32 he established his own firm, the Ceylon Manure Works, to manufacture, import and sell fertilizer. This later became A. Baur and Co. Ltd and diversified into other products and services. The firm, widely known and respected in Sri Lanka, celebrated its centenary in 1997.

Young Thilo Hoffmann’s main job as a Scientific/Agriculture Advisor at Baurs was ‘extension work’. He advised customers on the most suitable fertilizers, and the best agricultural practices, for tea, rubber and coconut, as well as paddy and minor crops. He prepared various fertilizer mixtures, printed booklets for many types of crops and engaged in field work to assist planters and farmers.

Among other things, Hoffmann pioneered a new system for the manual manuring of coconut. This was to turn the soil with mammoties, followed by thatching if possible, instead of opening and closing a trench around each palm as was then the custom. He personally demonstrated the new method in many estates and small-holdings. Today it is the general practice in Sri Lanka.

Thilo frequently visited the three crop Research Institutes – Tea, Rubber and Coconut – and various sections of the Department of Agriculture in Peradeniya. At these places he discussed problems and solutions with the different scientists, especially in the fields of soil chemistry, entomology and mycology (pests and diseases).

He vividly remembers when in 1947 the ‘blister blight’ disease of tea broke out in the hills of Ceylon. It was feared that it would be as disastrous as the ‘coffee rust’ which had ruined that industry about a 100 years before. Thilo was one of the first to experiment with, and then market (for Baurs), a copper spray from Switzerland as an efficient remedy.

That was the time when DDT, the first successful synthetic insecticide, was developed by a Swiss chemist. Thilo recalls how carelessly the new material was handled, because its long-term toxicity was realized only later. Today it is banned nearly worldwide. After the Second World War it was applied on countless humans to control parasites such as lice and fleas. It was also very successfully used in malaria control. Thilo himself took no precautions, freely using the concentrated powder with his bare hands and getting soaked by the spray.

A notable instance was the first time Thilo and his newly-wed wife Mae invited the Managing Director of Baurs, Mr A. O. Haller and his wife to dinner at their small flat. Mae had often complained about being bitten by something, but Thilo ignored her. Now she brought to his office a matchbox in which she had caught one of her tormentors and demanded to know what it was.

Thilo, after consulting some books, found it was a bedbug. He had samples of 50% DDT wettable powder in his laboratory. These he took to their veranda, and threw handfuls at chairs, beds and mattresses, banging them on the floor so the bugs fell off into an ever-thickening layer of DDT. By evening the powder had been removed, and the floors and furniture washed and polished.

“It was the only time we had bedbugs in our home,” says Thilo. They were then common in cinemas, and people took along newspapers to sit on. On returning home one immediately undressed in a place where the insects would show against the background.

One of Thilo’s first tasks at Baurs was to report on a new method of manuring paddy by sending alternating electrical current through the soil, invented by a local engineer. This was given wide publicity in the front pages of local newspapers. The Baurs boss feared for his fertilizer business. After visiting the trial plot in Colombo, Thilo’s report categorically excluded any possible effectiveness of the method.

“Are you sure?” asked the boss. So much had he been affected by the sensational reporting, which claimed that fertilizers had become redundant. After a few months the whole thing just disappeared and was never heard of again.

Many Ceylonese landowners were keen to manage their properties in an optimal manner, and would readily seek Thilo’s advice. Eventually, he became a specialist in coconut cultivation, and was asked to advise plantation companies abroad, in Malaysia and Papua New Guinea for example. He frequently visited Arcadia Estate in Perak with the owner, his friend G. G. Ponnambalam Sr.

Thilo was surprised to find that the Chettiars, the South Indian bankers operating mainly out of the Pettah, were dedicated agriculturalists. Only the best was good enough for the coconut properties they took over in the course of their business. He visited many of these, and was always received with respect, treated to excellent hot meals served on washed and smoked fresh banana leaves and eaten in the traditional eastern way. Usually an interpreter was needed as the owner did not speak English. Thilo’s recommendations were scrupulously followed.

The Baurs plantations

Three months after Thilo arrived in Colombo he was sent up-country to one of Baurs’ tea estates to familiarize himself with all practical aspects of tea planting. He recalls:

I took the night train from Maradana to Bandarawela which arrived there at six in the morning. I had a separate, very clean, wood-panelled cabin with a washbasin. It was as good as any first-class sleeper in Europe. The attendants were in uniform and neatly dressed. Proper white linen was provided for bed sheets. Meals were served in the dining car, run by the Victoria catering service. It was similar to a good resthouse of those times with spotless tablecloth, cutlery and crockery and a vase of flowers on the table.

Thilo was met in the cold morning at the Bandarawela station by Paul Hausmann, the Swiss superintendent of Kinellan Estate at Ella, and taken to the spacious bungalow there, where he was to live and work for two months, until the latter went on home leave. Then he moved to Chelsea Estate off the Bandarawela-Etampitiya road. This was nearly 600 acres in extent and also owned by Baurs.

Between the two tea estates he had to spend a few days at the Bandarawela Hotel, owned by Millers Ltd. There for the first time he saw a bucket latrine. All the rooms had this arrangement. Special labourers had to change the buckets several times a day through a separate door from the garden outside. Another place with the same system then was the Kalkudah resthouse.

At the time European shop assistants and tailors were still employed by Millers and Cargills in all their branches, and by Apothecaries and Whiteaways in Colombo. For several years after the war there were thousands of British and Allied military personnel in Sri Lanka, gradually being demobilized and sent back to their home countries. Many military camps and airfields lay across the island, with the main bases at Colombo, Trincomalee, Kandy, Katunayaka and Diyatalawa.

There were then about 5,000 British planters in tea and rubber estates. Practically all would have left the country by the early 1970s. Thilo recalls how social life and sports were centred on the many clubs which dotted the planting districts. Most have disappeared now, in contrast to India, where British-style club life continues almost unchanged. Planters’ wives tended bungalow gardens which often were outstanding.

The monotony of life in these areas was broken by visits from Chinese hawkers, who brought on bicycles large bundles of Chinese goods wrapped in oil-cloth: embroidered tablecloths, tablemats, household linen and carved knick-knacks. Linen was kept in a camphorwood chest from China to protect it against damp and vermin. There were Chinese shops in the larger towns. The 200-odd descendants of these people were given Sri Lankan citizenship in 2008.Another feature was the presence of ‘Afghan’ (Baluchi) money-lenders moving about on large motorcycles. The tall men in their typical dress were especially conspicuous on pay days, also in Colombo and other towns.

Thilo completed his practical training at Chelsea Estate under George Knox, a senior Uva planter, and returned to Colombo in March 1947. Eight years later, in 1955, he became a Director at Baurs. The scope of his work at the firm widened.

Amongst other things, he took charge of Baurs’ own plantations. As an agronomist, he had a particular liking for estate work, and visited the four tea estates owned by them, which were Clarendon-Avoca in Dimbula, Uva Ben Head, Chelsea and Kinellan in Uva, and their two coconut estates, Palugaswewa and Polontalawa, at least twice a year. For decades he was a member of the committee of the Low Country Products Association (LCPA) and of the Agency Section of the Planters’ Association of Ceylon.

All the Baurs estates were well run. The Clarendon mark frequently topped the tea market. Palugaswewa was the highest-yielding coconut property in the world. Polontalawa was developed from jungle in the 1960s and had, apart from coconut, over 200 acres of lift-irrigated paddy land which produced the first basmati rice in Sri Lanka.

In the mid 1960s the Tea Research Institute engaged a new Director who came from East Africa. Surprised to find that tea in Sri Lanka was grown under shade, he convinced planters that the removal of shade trees would result in higher yields. As a result, the appearance of the up-country tea districts changed dramatically. Thilo opposed this policy for agronomic and ecological reasons, and soon Baurs’ tea estates stood out among their treeless neighbours.

With the change yields did increase, but later levelled out and then declined. Today many tea estates have reverted to shade, high and light in the wet zone, two-tiered (for example, grevillea and dadap) in dry regions such as Uva.

Thilo felt acutely the loss of the Baurs plantations when all properties over 50 acres were nationalized in the 1970s under ‘Land Reform’ – which he describes as a “mislabelled political act”. About two decades later the country’s main plantation industries had been ruined, and the better estates were re-privatized on long-term leases.

This Thilo criticizes, because instead of permitting numbers of small and medium firms and even individuals to participate, some two dozen large companies were created, thus concentrating management of tea, rubber, and to a lesser extent coconut, plantations in a few hands.

After nationalization Baurs were left with a small portion of Uva Ben Head Estate at Welimada, about 1,200 m above sea level. The well-equipped bungalow there has served Thilo as a base for many excursions in the mountains and to other parts of the country, especially to the East.

Baurs were the major innovators in coconut cultivation in Sri Lanka. Palugaswewa Estate, near Bangadeniya, had been developed by the founder of the firm in the 19th century. After the Second World War it was producing over six million nuts on 1,400 acres, or 5,000 nuts per cultivated acre per year, which is 80 nuts per palm on average. The Swiss Superintendent Xavier Jobin and Thlo were responsible for this achievement.

After nationalization in 1974 the total annual yield had dropped to two million and the nuts had become smaller: 25% more, or 1,500, were needed to produce a candy (218 kg) of copra.

(To be continued)

Features

The call for review of reforms in education: discussion continues …

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The statement by 94 university teachers deplores the high handed manner in which the reforms were hastily formulated, and without public consultation. It underlines the problems with the substance of the reforms, particularly in the areas of the structure of education, and the content of the text books. The problem lies at the very outset of the reforms, with the conceptual framework. While the stated conceptualisation sounds fancifully democratic, inclusive, grounded and, simultaneously, sensitive, the detail of the reforms-structure itself shows up a scandalous disconnect between the concept and the structural features of the reforms. This disconnect is most glaring in the way the secondary school programme, in the main, the junior and senior secondary school Phase I, is structured; secondly, the disconnect is also apparent in the pedagogic areas, particularly in the content of the text books. The key players of the “Reforms” have weaponised certain seemingly progressive catch phrases like learner- or student-centred education, digital learning systems, and ideas like moving away from exams and text-heavy education, in popularising it in a bid to win the consent of the public. Launching the reforms at a school recently, Dr. Amarasuriya says, and I cite the state-owned broadside Daily News here, “The reforms focus on a student-centered, practical learning approach to replace the current heavily exam-oriented system, beginning with Grade One in 2026 (https://www.facebook.com/reel/1866339250940490). In an address to the public on September 29, 2025, Dr. Amarasuriya sings the praises of digital transformation and the use of AI-platforms in facilitating education (https://www.facebook.com/share/v/14UvTrkbkwW/), and more recently in a slightly modified tone (https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/PM-pledges-safe-tech-driven-digital-education-for-Sri-Lankan-children/108-331699).

The idea of learner- or student-centric education has been there for long. It comes from the thinking of Paulo Freire, Ivan Illyich and many other educational reformers, globally. Freire, in particular, talks of learner-centred education (he does not use the term), as transformative, transformative of the learner’s and teacher’s thinking: an active and situated learning process that transforms the relations inhering in the situation itself. Lev Vygotsky, the well-known linguist and educator, is a fore runner in promoting collaborative work. But in his thought, collaborative work, which he termed the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is processual and not goal-oriented, the way teamwork is understood in our pedagogical frameworks; marks, assignments and projects. In his pedagogy, a well-trained teacher, who has substantial knowledge of the subject, is a must. Good text books are important. But I have seen Vygotsky’s idea of ZPD being appropriated to mean teamwork where students sit around and carry out a task already determined for them in quantifying terms. For Vygotsky, the classroom is a transformative, collaborative place.

But in our neo liberal times, learner-centredness has become quick fix to address the ills of a (still existing) hierarchical classroom. What it has actually achieved is reduce teachers to the status of being mere cogs in a machine designed elsewhere: imitative, non-thinking followers of some empty words and guide lines. Over the years, this learner-centred approach has served to destroy teachers’ independence and agency in designing and trying out different pedagogical methods for themselves and their classrooms, make input in the formulation of the curriculum, and create a space for critical thinking in the classroom.

Thus, when Dr. Amarasuriya says that our system should not be over reliant on text books, I have to disagree with her (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/29/education-reform-to-end-textbook-tyranny ). The issue is not with over reliance, but with the inability to produce well formulated text books. And we are now privy to what this easy dismissal of text books has led us into – the rabbit hole of badly formulated, misinformed content. I quote from the statement of the 94 university teachers to illustrate my point.

“The textbooks for the Grade 6 modules . . . . contain rampant typographical errors and include (some undeclared) AI-generated content, including images that seem distant from the student experience. Some textbooks contain incorrect or misleading information. The Global Studies textbook associates specific facial features, hair colour, and skin colour, with particular countries and regions, and refers to Indigenous peoples in offensive terms long rejected by these communities (e.g. “Pygmies”, “Eskimos”). Nigerians are portrayed as poor/agricultural and with no electricity. The Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy textbook introduces students to “world famous entrepreneurs”, mostly men, and equates success with business acumen. Such content contradicts the policy’s stated commitment to “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Is this the kind of content we want in our textbooks?”

Where structure is concerned, it is astounding to note that the number of subjects has increased from the previous number, while the duration of a single period has considerably reduced. This is markedly noticeable in the fact that only 30 hours are allocated for mathematics and first language at the junior secondary level, per term. The reduced emphasis on social sciences and humanities is another matter of grave concern. We have seen how TV channels and YouTube videos are churning out questionable and unsubstantiated material on the humanities. In my experience, when humanities and social sciences are not properly taught, and not taught by trained teachers, students, who will have no other recourse for related knowledge, will rely on material from controversial and substandard outlets. These will be their only source. So, instruction in history will be increasingly turned over to questionable YouTube channels and other internet sites. Popular media have an enormous influence on the public and shapes thinking, but a well formulated policy in humanities and social science teaching could counter that with researched material and critical thought. Another deplorable feature of the reforms lies in provisions encouraging students to move toward a career path too early in their student life.

The National Institute of Education has received quite a lot of flak in the fall out of the uproar over the controversial Grade 6 module. This is highlighted in a statement, different from the one already mentioned, released by influential members of the academic and activist public, which delivered a sharp critique of the NIE, even while welcoming the reforms (https://ceylontoday.lk/2026/01/16/academics-urge-govt-safeguard-integrity-of-education-reforms). The government itself suspended key players of the NIE in the reform process, following the mishap. The critique of NIE has been more or less uniform in our own discussions with interested members of the university community. It is interesting to note that both statements mentioned here have called for a review of the NIE and the setting up of a mechanism that will guide it in its activities at least in the interim period. The NIE is an educational arm of the state, and it is, ultimately, the responsibility of the government to oversee its function. It has to be equipped with qualified staff, provided with the capacity to initiate consultative mechanisms and involve panels of educators from various different fields and disciplines in policy and curriculum making.

In conclusion, I call upon the government to have courage and patience and to rethink some of the fundamental features of the reform. I reiterate the call for postponing the implementation of the reforms and, in the words of the statement of the 94 university teachers, “holistically review the new curriculum, including at primary level.”

(Sivamohan Sumathy was formerly attached to the University of Peradeniya)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Sivamohan Sumathy

Features

Constitutional Council and the President’s Mandate

The Constitutional Council stands out as one of Sri Lanka’s most important governance mechanisms particularly at a time when even long‑established democracies are struggling with the dangers of executive overreach. Sri Lanka’s attempt to balance democratic mandate with independent oversight places it within a small but important group of constitutional arrangements that seek to protect the integrity of key state institutions without paralysing elected governments. Democratic power must be exercised, but it must also be restrained by institutions that command broad confidence. In each case, performance has been uneven, but the underlying principle is shared.

Comparable mechanisms exist in a number of democracies. In the United Kingdom, independent appointments commissions for the judiciary and civil service operate alongside ministerial authority, constraining but not eliminating political discretion. In Canada, parliamentary committees scrutinise appointments to oversight institutions such as the Auditor General, whose independence is regarded as essential to democratic accountability. In India, the collegium system for judicial appointments, in which senior judges of the Supreme Court play the decisive role in recommending appointments, emerged from a similar concern to insulate the judiciary from excessive political influence.

The Constitutional Council in Sri Lanka was developed to ensure that the highest level appointments to the most important institutions of the state would be the best possible under the circumstances. The objective was not to deny the executive its authority, but to ensure that those appointed would be independent, suitably qualified and not politically partisan. The Council is entrusted with oversight of appointments in seven critical areas of governance. These include the judiciary, through appointments to the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, the independent commissions overseeing elections, public service, police, human rights, bribery and corruption, and the office of the Auditor General.

JVP Advocacy

The most outstanding feature of the Constitutional Council is its composition. Its ten members are drawn from the ranks of the government, the main opposition party, smaller parties and civil society. This plural composition was designed to reflect the diversity of political opinion in Parliament while also bringing in voices that are not directly tied to electoral competition. It reflects a belief that legitimacy in sensitive appointments comes not only from legal authority but also from inclusion and balance.

The idea of the Constitutional Council was strongly promoted around the year 2000, during a period of intense debate about the concentration of power in the executive presidency. Civil society organisations, professional bodies and sections of the legal community championed the position that unchecked executive authority had led to abuse of power and declining public trust. The JVP, which is today the core part of the NPP government, was among the political advocates in making the argument and joined the government of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga on this platform.

The first version of the Constitutional Council came into being in 2001 with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution during the presidency of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. The Constitutional Council functioned with varying degrees of effectiveness. There were moments of cooperation and also moments of tension. On several occasions President Kumaratunga disagreed with the views of the Constitutional Council, leading to deadlock and delays in appointments. These experiences revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of the model.

Since its inception in 2001, the Constitutional Council has had its ups and downs. Successive constitutional amendments have alternately weakened and strengthened it. The 18th Amendment significantly reduced its authority, restoring much of the appointment power to the executive. The 19th Amendment reversed this trend and re-established the Council with enhanced powers. The 20th Amendment again curtailed its role, while the 21st Amendment restored a measure of balance. At present, the Constitutional Council operates under the framework of the 21st Amendment, which reflects a renewed commitment to shared decision making in key appointments.

Undermining Confidence

The particular issue that has now come to the fore concerns the appointment of the Auditor General. This is a constitutionally protected position, reflecting the central role played by the Auditor General’s Department in monitoring public spending and safeguarding public resources. Without a credible and fearless audit institution, parliamentary oversight can become superficial and corruption flourishes unchecked. The role of the Auditor General’s Department is especially important in the present circumstances, when rooting out corruption is a stated priority of the government and a central element of the mandate it received from the electorate at the presidential and parliamentary elections held in 2024.

So far, the government has taken hitherto unprecedented actions to investigate past corruption involving former government leaders. These actions have caused considerable discomfort among politicians now in the opposition and out of power. However, a serious lacuna in the government’s anti-corruption arsenal is that the post of Auditor General has been vacant for over six months. No agreement has been reached between the government and the Constitutional Council on the nominations made by the President. On each of the four previous occasions, the nominees of the President have failed to obtain its concurrence.

The President has once again nominated a senior officer of the Auditor General’s Department whose appointment was earlier declined by the Constitutional Council. The key difference on this occasion is that the composition of the Constitutional Council has changed. The three representatives from civil society are new appointees and may take a different view from their predecessors. The person appointed needs to be someone who is not compromised by long years of association with entrenched interests in the public service and politics. The task ahead for the new Auditor General is formidable. What is required is professional competence combined with moral courage and institutional independence.

New Opportunity

By submitting the same nominee to the Constitutional Council, the President is signaling a clear preference and calling it to reconsider its earlier decision in the light of changed circumstances. If the President’s nominee possesses the required professional qualifications, relevant experience, and no substantiated allegations against her, the presumption should lean toward approving the appointment. The Constitutional Council is intended to moderate the President’s authority and not nullify it.

A consensual, collegial decision would be the best outcome. Confrontational postures may yield temporary political advantage, but they harm public institutions and erode trust. The President and the government carry the democratic mandate of the people; this mandate brings both authority and responsibility. The Constitutional Council plays a vital oversight role, but it does not possess an independent democratic mandate of its own and its legitimacy lies in balanced, principled decision making.

Sri Lanka’s experience, like that of many democracies, shows that institutions function best when guided by restraint, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to the public good. The erosion of these values elsewhere in the world demonstrates their importance. At this critical moment, reaching a consensus that respects both the President’s mandate and the Constitutional Council’s oversight role would send a powerful message that constitutional governance in Sri Lanka can work as intended.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Gypsies … flying high

The scene has certainly changed for the Gypsies and today one could consider them as awesome crowd-pullers, with plenty of foreign tours, making up their itinerary.

The scene has certainly changed for the Gypsies and today one could consider them as awesome crowd-pullers, with plenty of foreign tours, making up their itinerary.

With the demise of Sunil Perera, music lovers believed that the Gypsies would find the going tough in the music scene as he was their star, and, in fact, Sri Lanka’s number one entertainer/singer,

Even his brother Piyal Perera, who is now in charge of the Gypsies, admitted that after Sunil’s death he was in two minds about continuing with the band.

However, the scene started improving for the Gypsies, and then stepped in Shenal Nishshanka, in December 2022, and that was the turning point,

With Shenal in their lineup, Piyal then decided to continue with the Gypsies, but, he added, “I believe I should check out our progress in the scene…one year at a time.”

The original Gypsies: The five brothers Lal, Nimal, Sunil, Nihal and Piyal

They had success the following year, 2023, and then decided that they continue in 2024, as well, and more success followed.

The year 2025 opened up with plenty of action for the band, including several foreign assignments, and 2026 has already started on an awesome note, with a tour of Australia and New Zealand, which will keep the Gypsies in that part of the world, from February to March.

Shenal has already turned out to be a great crowd puller, and music lovers in Australia and New Zealand can look forward to some top class entertainment from both Shenal and Piyal.

Piyal, who was not much in the spotlight when Sunil was in the scene, is now very much upfront, supporting Shenal, and they do an awesome job on stage … keeping the audience entertained.

Shenal is, in fact, a rocker, who plays the guitar, and is extremely creative on stage with his baila.

‘Api Denna’ Piyal and Shenal

Piyal and Shenal also move into action as a duo ‘Api Denna’ and have even done their duo scene abroad.

Piyal mentioned that the Gypsies will feature a female vocalist during their tour of New Zealand.

“With Monique Wille’s departure from the band, we now operate without a female vocalist, but if a female vocalist is required for certain events, we get a solo female singer involved, as a guest artiste. She does her own thing and we back her, and New Zealand requested for a female vocalist and Dilmi will be doing the needful for us,” said Piyal.

According to Piyal, he originally had plans to end the Gypsies in the year 2027 but with the demand for the Gypsies at a very high level now those plans may not work out, he says.

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition