Features

The World after Gorbachev and Sri Lanka after JR Jayewardene

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev who died last Tuesday was hardly known outside the Soviet Union when JR Jayewardene made himself Sri Lanka’s President in 1978. Seven years later, on March 11, 1985, Gorbachev would be become the General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. He was 54 years old and was the first leader of the Soviet Union born after the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution that turned Tsarist Russia into the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics (USSR).

He was also the one to preside over the dissolution of both the Communist Party and the Soviet Union. He announced his resignation as Soviet President and Commander Chief on Christmas Day 1991. The changes he unleashed in little over six years are still reverberating throughout the world and more so in the attritive war between Russia and the Ukraine, the two largest republics of the old USSR.

Sri Lankans have had a split attitude towards the October revolution and the Soviet Union thereafter. There were those who were fascinated and inspired by the October revolution, and others who felt threatened and were fearful of its ripples reaching the shores of feudal Sri Lanka. Such fears were not unwarranted.

The Sri Lankan Left movement that emerged in the 1930s was both inspired by the example of the Soviet Union and also vigorously carried into Sri Lanka the bitter ideological disputes among Russian Bolsheviks. The UNP governments after independence were markedly pro-western and anti-Soviet in their foreign policy. The SLFP governments after 1956 took a much friendlier attitude towards the Soviet Union as part of their non-aligned approach to international relations.

The Third World exuberance over global decolonization in the 1960s further augmented the Soviet-Sri Lankan relationship. The Soviet Union and other East European socialist countries became new destinations and scholarship sources for young Sri Lankan students and professionals seeking university education and qualifications.

New cross-sections of Sri Lankan society benefited from the new foreign openings, which until then had been limited to students from traditional elite circles going to western, mostly British, universities. Literary connections were established through translations of writings between the Russian and Sinhala and Tamil languages.

The economic nationalism of the era led to the opening of several industrial corporations directly based on Soviet financial and technological support, in areas where import substitution had become necessary and for which there has been no private sector interest despite years of trying. What no one remembers now is that state industrial corporations were first established by GG Ponnambalam, the self-acknowledged “unrepentant opponent of socialism,” but a brilliant Minister (of Industries) in the DS Senanayake (UNP) government after independence.

Some of them were against the recommendations of World Bank experts, which were equally expertly rejected by Ponnambalam. Ponnambalam’s ministry even delicensed failing private industries, so much so that Pieter Keuneman, a young Communist MP at that time, mockingly called Ponnambalam the “vitriolic minister” for ‘dissolving’ small private industries.

The highpoint of Sri Lankan economic nationalism in the 1960s was the nationalization of the petroleum industry and the setting up of the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) to take over what was then the monopoly of three global multinationals, Shell, Esso and Caltex. Interestingly, it was the UNP government (1965-70) of Dudley Senanayake that built the oil refinery in Sapugaskanda for the state petroleum corporation to refine crude oil from Iran for local consumption and potential exports.

Through all the economic crisis and shortcomings of industrial corporations that marked the 1970-77 United Front government, the CPC’s performance at Sapugaskanda was steady and even a new urea plant was built next door (by the State Fertilizer Manufacturing Corporation) to produce urea (for fertilizer for domestic agriculture) using naphtha, a byproduct from the refinery.

However, the economic changes after 1977 hugely increased the demand for petroleum products, and for electricity, and the CPC and CEB were stretched virtually overnight beyond their production capacities. The UNP government decided to export naphtha, shut down the new fertilizer factory, and hand it over to a private business for producing nails!

As I wrote a few weeks ago, it is now poetic justice for Ranil Wickremesinghe to be called upon as President to put Sri Lanka’s petroleum and electricity houses in order after they were neglected and mismanaged over 17 years (1977-94) by the UNP government of JR Jayewardene in which he (RW) was a cabinet apprentice.

From Gorbachev to Putin

It was during the same 17 years that President Jayewardene introduced fundamental changes to Sri Lanka’s political and economic systems. And over six years (1985-91) midway through that period, General Secretary Gorbachev launched far reaching changes within the Soviet Communist Party on the then famous planks of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), hoping for the inner-party changes to spill over into the broader Soviet society and institutions. Gorbachev pursued both political and economic restructuring, in contrast to China which focused on a thoroughgoing economic restructuring while maintaining the Communist Party’s stranglehold over the political system and society. The changes worked in China but failed in the Soviet Union.

China did not have the burdens that Gorbachev had to unload off the Soviet Union: a complex and multi-ethnic federal system under the control of a single Party; the costly system of political and military control over Warsaw Pact countries; and the blood sucking war in Afghanistan. In addition, the Soviet economy that recorded impressive strides in the pre-war and post-war periods (a fact now acknowledged by mainstream economists) had irretrievably fallen to the pits during the long, soporific tenure of Leonid Brezhnev (generally attributed to Cold War military budgets and poorly advised resource allocations and production priorities). The Soviet political system was also not easily amenable to radical changes because of its entrenched bureaucracy, depleted institutions and a stunted civil society.

At the same time, Gorbachev’s changes created far reaching effects in Europe and worldwide. He pulled Soviet Union out of the Afghan quagmire. He successfully forced nuclear disarmament treaties on the US and on NATO. And he let the Berlin Wall fall, which many consider to be the beginning of the post-colonial phase of globalization. East European countries broke free of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union itself, much to Gorbachev’s mortification, imploded leaving Russia alone in its winter of discontent without a Tsar and without a Politburo. He was reviled in Russia but was celebrated in the west. For all their public adulations, however, western leaders, especially the US, did not purposefully and sincerely support Gorbachev achieve his perestroika goals.

While Prime Minister Thatcher and President Reagan publicly warmed up to the man, they did not persistently overrule the hawks in their administrations and in NATO who resisted change on the grounds that they could not trust Gorbachev. The American Right believed that it was America’s economic strength and military might that forced the Soviet Union to accept ‘defeat’ in the Cold War and adopt glasnost and perestroika changes. This thesis has been consistently debunked by western historians, most notably by Oxford University’s Archie Brown who has reminded that Gorbachev’s emergence in the Soviet had nothing to do with any US policy.

The West’s biggest betrayal has been over its unwritten undertaking to Gorbachev that NATO will not expand into Eastern Europe following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw agreements. NATO and the West went ahead expanding and collecting new members regardless of Gorbachev’s protestations from retirement. The NATO expansion is the most weighted single factor behind the emergence of Putin and now his war in Ukraine.

Nina Khrushcheva, a Professor at New York’s New School and the great-granddaughter of Khrushchev who ordered the Berlin wall built in 1961, has recalled in her obituary what Gorbachev told her when she asked him why he did not send tanks to Germany in 1989 to protect the wall: “We shouldn’t dictate to sovereign countries their way of life.” Gorbachev stood by that principle all through his six years in office, and has lived by it for over thirty years after retirement.

On the other hand, Gorbachev’s principle of non-interference has been repudiated not only by Russia’s Putin but also by the West and NATO. To wit, the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, two invasions of Iraq, another long distance war in Afghanistan, and continuing imbroglios in the Middle East and North Africa. And the Western countries that fomented and cheered disruptions in Eastern Europe as democratic revolutions, are now having democracy threatened in their own countries by new populist manifestations of the old forces of race, bigotry and fascism.

The emergences of Boris Johnson in Britain and of Donald Trump in America are not accidental aberrations. While Britain has been able to get rid of Johnson without too much fuss thanks to the parliamentary system, the US with its presidential system is stuck with Trump even after getting him out of office after a single term.

From JRJ to Ranil-Rajapaksa

For the rest of the world, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of China as a market economy powerhouse have meant the removal of the Socialist Second World from the world order. The Left Parties in the Third World lost their external reference points for the argument for socialism in developing countries or emerging economies. In Sri Lanka, the 1977 victory of JR Jayewardene was an electoral repudiation of the people’s experience of what was politically bandied as socialism over nearly two decades. But President Jayewardene’s agenda went beyond more than reviving the economy and relieving people of their scarcities.

While Gorbachev’s reforms in the Soviet Union were intended to open up politics and facilitate power sharing, Jayewardene’s agenda was to centralize and personalize executive power behind the facades of the old parliamentary system. Where Gorbachev failed, President Jayewardene succeeded almost perfectly by his expectations. But 45 years on, what was once celebrated as calculated political success has turned out to be a wholesale disaster for the country. Both economically and politically.

If the emergence of the Rajapaksas exposed the faults of the presidential system, the failed presidency of Gotabaya Rajapaksa has made everyone sick and tired of it. Enter Ranil Wickremesinghe, the apprentice in 1977 and now the elder statesman – first as Gotabaya’s Prime Minister, then as Acting President, and now as interim President, but actually carrying himself as if he is a new President elected by the people. It is not clear if President Wickremesinghe is now intending to get rid of the executive presidency, or if he will try to keep it at least a term longer so that he can make one last electoral go at it.

In addition to being President, Mr. Wickremesinghe is also his Minister of Finance. On Tuesday he presented the interim budget replacing Basil Rajapaksa’s non-budget for 2022. It was really a precursor to the IMF’s statement a day later that the IMF Team in Colombo and government officials have reached staff-level agreement to support the authorities’ economic adjustment and reform policies with a new US$2.9 billion funding facility over a 48-month period. The agreement is subject to ratification by the IMF Board in Washington.

The expectation is that the IMF agreement would help Sri Lanka obtain debt relief from Sri Lanka’s creditors along with additional financing from multilateral partners to help ensure debt sustainability and additional funding support. The infamous ‘haircuts’ that creditors should agree to bear are yet to come and the discussions around it are reportedly being facilitated by Japan. China remains non-committal even as its agreement is essential for reaching agreements with other bilateral creditors and private lenders. Haircuts can be significant and varying arrangements have been used for different countries in the past. The Russian experience in 1998-99 involved a rather ‘tough haircut’ (50-70%) for external creditors and more favourable treatment in dealing with domestic debt.

There are already calls against delaying and using different mechanisms for domestic debt restructuring to prevent the Employees’ Provident Fund going bankrupt and significant losses to domestic banks. A related political question that is bound to arise will be about the ‘haircuts’ that Sri Lanka’s parliamentarians, especially SLPP MPs, are willing to take for themselves. Already, many MPs are known to be against early elections to secure their pensions, and SLPP MPs are not looking for any haircut but prioritized compensation for damage to their properties during the May 9 violence that was in fact provoked by their own leaders. The President will have his handsful in determining who in parliament will get haircut and who will get compensation and in which order.

Mr. Wickremesinghe had it easy lecturing helpless government clerks in Anuradhapura that they should either work or go home. His words will carry far greater weight if he were to say to Nivard Cabraal that he is not entitled to extra pension, or to former Presidents that they are not entitled to government pensions and retirement residences if they continue to be active in politics and remain lawmakers in parliament. Mikhail Gorbachev lived for over 30 years after his retirement on meagre government support to which he was entitled. He did not look for any American Green Card but chose to remain in Russia, occasionally defending his legacy even though his legacy was already dead.

Features

The middle-class money trap: Why looking rich keeps Sri Lankans poor

Every January, we make grand resolutions about our finances. We promise ourselves we’ll save more, spend less, and finally get serious about investments. By March, most of these promises were abandoned, alongside our unused gym memberships.

Every January, we make grand resolutions about our finances. We promise ourselves we’ll save more, spend less, and finally get serious about investments. By March, most of these promises were abandoned, alongside our unused gym memberships.

The problem isn’t our intentions, it’s our approach. We treat financial management as a personality flaw that needs fixing, rather than a skill that needs the right strategy. This year let’s try something different. Let’s put actual behavioural science behind how we handle our rupees.

Based on the article ‘Seven proven, realistic ways to improve your finances in 2026’ published on 1news.co.nz, I aim to adapt these recommended financial strategies to the Sri Lankan context.” Here are seven money habits that work because they’re grounded in how humans actually behave, not how we wish we would.

While these strategies offer useful direction for strengthening personal financial management, it is important to acknowledge that they may not be suitable for everyone. Many households face severe financial pressure and cannot realistically follow traditional income allocation frameworks, such as the well-known but outdated Singalovada Sutta guidelines, when even meeting daily food expenses has become a struggle. For individuals and families who are burdened by escalating costs of essentials, including electricity, water, mobile connectivity, transport, and other non-negotiable commitments, strict adherence to prescriptive models is neither practical nor fair to expect. Therefore, readers should remain mindful of their own financial realities and adapt these strategies in ways that align with their income levels, essential obligations, and broader personal circumstances.

1. Your Money Problems Aren’t Moral Failures, They’re Data Points

When every rupee misspent becomes evidence of personal failure, we stop looking for solutions. Shame is a terrible problem-solver. It makes us hide from our bank statements, avoid difficult conversations, and repeat the same mistakes because we’re too embarrassed to examine them.

Instead, try replacing judgment with curiosity. Transform “I’m terrible with money” into “That’s interesting, why did I make that choice?” Suddenly, mistakes become information rather than indictments. You might notice you overspend at Odel or high-end restaurant when stressed about work. Or that you commit to expensive plans when feeling socially pressured. Perhaps your online shopping peaks during power cuts when you’re bored and frustrated.

2. Forget the Year-Long Marathon, Focus on 90-Day Sprints

A Sri Lankan year is densely packed with financial obligations: Sinhala/Tamil Avurudu, Christmas, Vesak, and Poson celebrations; recurring school fees; seasonal festival shopping; wedding and almsgiving periods; yearend festivities; and an evergrowing list of marketing-driven occasions such as Valentine’s Day, Father’s Day, Mother’s Day, and many others. Each of these events carries its own financial weight, often placing additional pressure on already-stretched household budgets.

Research consistently shows that shorter time frames work better. Ninety days is long enough to create a meaningful change, but short enough to maintain focus and momentum. So instead of one overwhelming annual goal, give yourself four quarterly upgrades.

In the first quarter, the focus may be on organising your contributions toward key duties and responsibilities, while also ensuring that you are maximising the available benefits for your designated beneficiaries. Quarter two could be about building a small emergency fund, even Rs. 10,000 provides breathing room. Quarter three might involve auditing your bills and subscriptions to eliminate unnecessary expenses. Quarter four could be when you finally start that investment you’ve been postponing. You don’t need superhuman discipline or complicated spreadsheets, just focused attention, one quarter at a time.

3. Make One Decision That Eliminates Weekly Worry

The best money decisions are the ones you make once but benefit from repeatedly. These are decisions that permanently reduce what behavioural economists call “decision fatigue”, the mental exhaustion that comes from constantly managing money in your head. What’s one choice you could make today that would remove a recurring financial worry?

It might be setting up an automatic standing order to transfer Rs. 10,000 to savings the day your salary arrives, before you can spend it. Maybe it’s consolidating your scattered savings accounts into one that actually pays decent return.

These aren’t dramatic moves that require personality transplants. They’re structural decisions that work with your human tendency toward inertia rather than against it. Most banks now offer seamless digital automation. You can set it up once and benefit from that decision every single month without additional effort or willpower. You make the decision once. You benefit all year. That’s leveraging your energy intelligently.

4. Stop Spending on Who You Think You Should Be

Sri Lankan society comes with heavy expectations. The car you drive, the school your children attend, the hotels you patronise, the brands you wear, all communicate your worth, or so we’re told. Much of our spending isn’t about actual enjoyment. It’s about meeting unspoken expectations, keeping up appearances, or aspiring to a version of us that doesn’t actually exist.

We buy expensive saris we’ll wear once because everyone does. We maintain memberships to clubs we rarely visit because it looks good. We say yes to weekend plans at overpriced restaurants because declining feels like admitting we can’t afford it. We upgrade phones not because ours stopped working, but because others have.

Before your next purchase, ask yourself: do I actually want this, or do I want to want it? If it’s the second one, walk away. You won’t miss it. This isn’t about deprivation, it’s about precision. When you stop spending to perform and start spending to support the life you genuinely enjoy, money pressure eases dramatically. Your resources align with your actual values rather than imagined expectations.

Maybe you don’t care about fancy restaurants, but you love long drives along the southern coast. Maybe branded clothing leaves you cold, but you’d spend any amount on art supplies or books. That’s fine. Spend accordingly.

5. Break One Habit, See If You Actually Miss It

We’re creatures of routine, which serves us well until those routines outlive their usefulness. Sometimes we spend money on habits that started for good reasons but no longer serve us. Alpechchathava, in Buddha’s teaching, means living contentedly with few desires. It guides a person to manage money wisely by avoiding excess spending, unnecessary debt, and craving, and by focusing on essential needs and wholesome priorities. In this way, wealth supports mental cultivation, generosity, and spiritual progress.

The daily kottu roti that once felt like a convenient solution after working late may now have turned into an unnecessary routine. Similarly, frequent P&S or Caravan snack runs, and the habit of picking up sugary treats like cakes and sweets, are not only costly but also wellknown to be unhealthy, as nutritionists consistently point out. Beyond food, other expenses such as magazine subscriptions, the monthly coffee meetup, or weekend mall browsing often continue on autopilot without us realising how much they add up. These seemingly small, habitual expenses can quietly drain your budget while offering very little longterm value.

Try this experiment: keep a money diary for one week. Note every expense, no matter how small. Then identify one regular spend and eliminate it for the following week. If you don’t miss it? Excellent, keep it gone. If you genuinely miss it? Add it back without guilt. This isn’t about permanent sacrifice.

It’s about snapping yourself out of autopilot and checking whether your spending still reflects your current reality, priorities and purchasing power. You might discover you’re spending Rs. 15,000 monthly on things you barely notice.

6. Create Your Crisis Playbook on a Good Day

Many financial disasters don’t happen because we’re careless, they happen because we’re panicked. When crisis strikes, job loss, medical emergency, unexpected business downturn, fear hijacks our decision-making. Our rational brain exists while panic makes expensive choices: high-interest personal loans, selling investments at losses, making commitments we can’t sustain.

The solution? Make your crisis plan before the crisis arrives. On a calm day, sit down and document: If I lost my income tomorrow, what would I do first? Which expenses are truly essential? What’s the absolute minimum I need to function? Who could I call for advice? Which savings are untouchable, which could be accessed if necessary? What government support or loan restructuring options exist (Not in Sri Lanka)? This is a sort of preparation for sudden shocks.

7. Question the Money Stories You Inherited

Sometimes our biggest financial obstacles aren’t failed attempts, they’re the attempts we never make because we’ve internalised limiting stories. “Our family was never good with money.” “Investing is for rich people.” “I’m just not the type who earns more.” “Women don’t understand finance.” These narratives, absorbed from family, culture, or past experiences, become invisible fences.

Question them. Where did this belief originate? Is it actually true, or is it a story you’ve been telling yourself for so long, it feels like fact? What would happen if you tested it? Often, these stories protect us from the discomfort of trying and potentially failing. But they also protect us from the possibility of succeeding. And that’s a far costlier protection than most of us realise.

The Bottom Line

Improving your finances in 2026 doesn’t require becoming a different person. It requires understanding the person you already are, your patterns, triggers, and tendencies, and working with them rather than against them.

These aren’t magic solutions. They’re evidence-based approaches that acknowledge a simple truth: you’re not broken, and your money management doesn’t need fixing through willpower alone. It needs better systems, clearer thinking, and a lot less shame.

Features

Public scepticism regarding paediatric preventive interventions

A significant portion of the history of paediatrics is a triumph of prevention. From the simple act of washing hands to the miracle of vaccines, preventive strategies have been the unsung heroes, drastically lowering child mortality rates and setting the stage for healthier, longer lives across the globe. Simple measures like promoting personal hygiene, ensuring the proper use of toilets, and providing Vitamin K immediately after birth to prevent dangerous bleeding, have profound impacts. Advanced interventions like inhalers for asthma, robust trauma care systems, and even cutting-edge genetic manipulations are testament to the relentless and wonderful progress of paediatric science.

A shining beacon that has signified increased survival and marked reductions in mortality across the board in all paediatric age groups has been the development of various preventive strategies in the science of children’s health, from newborns to adolescents. The institution of such proven measures across the globe, has resulted in gains that are almost too good to be true. From a Sri Lankan perspective, these measures have contributed towards the unbelievable reduction of the under-5-year mortality rate from over 100 per 1000 live births in the 1960s to the seminal single-digit figure of 07 per 1000 live births in the 2020s.

Yet for all this, despite the overwhelming evidence of success, a most worrying trend is emerging. That is public scepticism and pessimism regarding these vital interventions. This doubt is not a benign phenomenon; it poses a real danger to the health of our children. At the heart of this challenge lies the potent, often insidious, spread of misinformation and disinformation.

The success of any preventive health strategy in paediatrics rests not just on its scientific efficacy, but on parental cooperation and commitment. When parents hesitate or refuse to follow recommended guidelines, the shield of prevention is compromised. Today, the most potent threat to this partnership is the flood of false information.

Misinformation is false information spread unintentionally. A well-meaning friend sharing a rumour about a vaccine side-effect they heard online is spreading misinformation.

Disinformation is false information deliberately created and disseminated to cause harm or sow doubt. This often comes from organised groups or individuals with vested interests; sometimes financial, sometimes ideological, who seek to undermine public trust in medical institutions and scientific consensus.

The digital age, particularly social media, has become the prime breeding ground for these falsehoods. Complex scientific data is reduced to emotionally charged, simplistic, and often sensationalist soundbites that travel faster and farther than the truth.

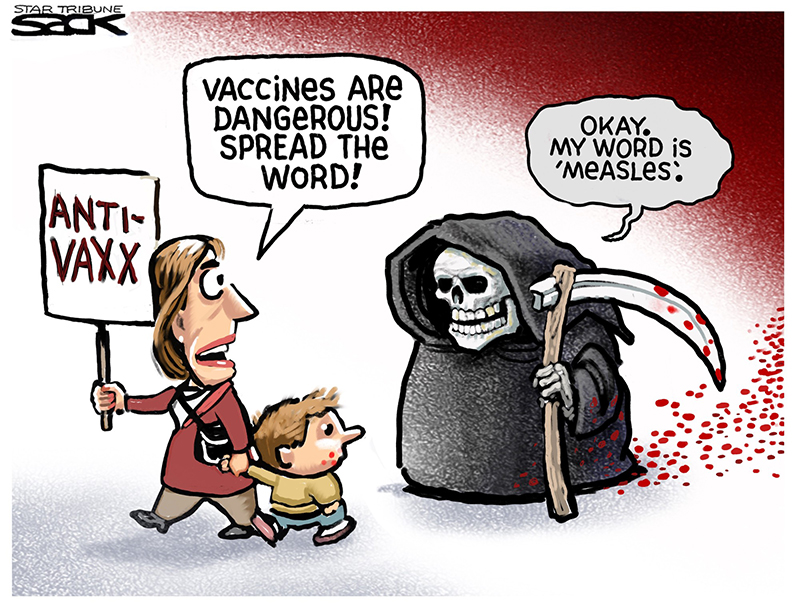

The most visible battleground is childhood vaccination. Decades of robust, high-quality research have confirmed vaccines as one of the most cost-effective and successful public health interventions ever conceived. Global vaccination efforts have saved an estimated 150 million lives in the past 50 years, eradicating or drastically controlling diseases like polio, measles, diphtheria, and tetanus.

However, a single, long-retracted, and scientifically debunked paper claiming a link between the Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism continues to be weaponised by disinformation campaigns. This persistent myth, despite being soundly disproven, taps into deep-seated fears about children’s development. Other common vaccine myths target ingredients such as trace amounts of aluminium or mercury, which are harmless in the quantities used and often less than what is naturally found in food or the idea that “natural immunity” from infection is superior, totally ignoring the fact that natural infection carries the devastating risk of severe complications, long-term disability, and even death. The tangible consequence of this doubt is the dropping of childhood vaccination rates in various communities, leading to the wholly unnecessary re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles.

Scepticism is not limited to vaccines. It can touch any area of paediatric preventive care where an intervention might seem unnecessary, invasive, or have perceived risks. Routine screenings for speech disorders, motor skills, or mental health issues can sometimes be perceived as medicalising normal childhood variations or putting a “label” on a child. Parents may resist or delay screening, missing the critical window for early intervention of proven measures that are likely to help. Advice on managing childhood obesity, reducing screen time, or adopting a balanced diet can be viewed by some parents as intrusive or judgmental, leading to poor adherence to essential health-promoting behaviours.

The regular use of inhalers for asthma or other chronic conditions might be looked down upon due to the fear of “dependency”, “addiction”, or long-term side effects, despite medical consensus that these preventive measures keep conditions controlled and prevent life-threatening exacerbations.

The common thread is a lack of understanding of the risk-benefit ratio. Parents, bombarded by fear-mongering narratives, often overestimate the rare, mild risks of an intervention while catastrophically underestimating the severe and permanent risks of the disease or condition itself.

The power of paediatric preventive medicine is not in a single shot or pill, but in the consistent, committed partnership between healthcare providers and parents. Paediatric science, driven by rigorous evidence-based medicine, do continue to refine guidelines, conduct transparent research, and communicate its findings clearly. When guidelines are confusing or lack robust evidence, it naturally creates openings for doubt. The scientific community’s commitment to continuous quality improvement and accessibility is paramount.

Ultimately, the success of prevention rests with the parents. Parenting, as a vital form of preventive care, includes all activities that raise happy, healthy, and capable children. The simple, non-medical steps mentioned in the introduction, proper handwashing, good sanitation, and encouraging exercise, are all forms of parental preventive intervention.

For more complex interventions, parental commitment requires several actions. They need to seek and trust the guidance provided by qualified healthcare professionals over anonymous, unsubstantiated online claims. They need to engage in an open dialogue by asking relevant questions and expressing concerns to doctors in an open, non-confrontational manner. A good healthcare provider will use this as an opportunity to educate and build trust, and not a portal to simply dismiss concerns. Then, of course, there is the spectre of adherence to various protocols and actions by the parents. These include consistently following recommended schedules, whether for well-child checkups, vaccinations, or daily medication protocols.

Addressing public scepticism requires a multi-pronged, collaborative strategy. It is not just about correcting false facts (debunking), but about building resilience against future falsehoods (prebunking). The single most influential voice in a parent’s decision-making process is their paediatrician or primary care provider. Clinicians must move beyond simply reciting facts. They need to use empathetic communication techniques, like Motivational Interviewing (MI), which focuses on active listening, validating parental concerns, and then collaboratively guiding them toward evidence-based decisions. For example, responding with, “I hear you’re worried about the side-effects you read about. Can I share what we know from decades of safety monitoring?” Being open about common, minor side effects such as a short-lasting fever after a vaccine pre-empts the shock and distrust that occurs when an expected, yet unmentioned, reaction happens.

Public health campaigns must go on the offensive, not just a defensive fact-checking spree. Teaching the general public how disinformation works, the use of “fake experts”, selective cherry-picked data, and conspiracy theories all add up to a most powerful form of inoculation (prebunking) against future exposure. Health institutions must simplify their communications and make verified, high-quality information easily accessible on platforms where parents are already looking.

Parents often trust their peers as much as their doctors. Engaging local community leaders, faith leaders, and even trusted social media influencers to share accurate, positive messages about paediatric health can shift the public narrative at a grassroots level. While protecting privacy, sharing aggregate data and stories about the dramatic decline in childhood diseases thanks to prevention can re-emphasise the collective good.

The battle against child mortality and morbidity has been one of the great human achievements, a testament to scientific ingenuity and collective effort. Today, the greatest threat to maintaining these gains is not a new virus, but a breakdown of trust fuelled by unchecked falsehoods.

Paediatric preventive interventions, from a cake of soap and a proper toilet to the most sophisticated genetic therapies, are the foundation of a healthy future for every child. To secure this future, the scientific community must remain transparent, the healthcare system must lead with empathy, and the public must commit to informed, critical thinking. By rejecting the noise of disinformation and embracing the clear, evidence-based consensus of science, we can ensure that every child continues to benefit from the life-saving progress that defines modern paediatrics. The well-being of the next generation demands nothing less than this renewed commitment.

Little children are not in a position to make abiding decisions regarding their health, especially regarding preventive strategies in health. It is ultimately the crucial decisions made by responsible parents regarding the health of their children that really matter. As doctors, our commitment is never to leave any child behind.

by Dr B. J. C. Perera ✍️

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health

Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Features

Attacks on PM vulgar, misogynistic; education reforms welcome

We express our profound concern and deep outrage at the vulgar, misogynistic, and defamatory attacks being directed at the Prime Minister and Minister of Education, Dr. Harini Amarasuriya.

Dr. Harini Amarasuriya is not merely a political leader; she is a scholar, public intellectual, and lifelong advocate of social justice, equality, and education. Attempts to discredit her through personal abuse rather than reasoned policy debate are not only an insult to her, but an assault on democratic values, women’s leadership, and intellectual integrity in public life.

Such attacks are unjust and unethical, and they corrode democratic discourse. We are deeply disappointed that certain political actors and their supporters continue to rely on misinformation, prejudice, and emotional manipulation, instead of engaging in rational, evidence-based, and constructive debate.

Sri Lanka has already paid a heavy price for decades of politics rooted in fear, communal division, and sentiment-driven populism. The country’s economic collapse and social breakdown are the direct consequences of these failed approaches. The people decisively rejected this style of politics through the Aragalaya, signaling a clear demand for change. Sri Lanka now stands at a historic turning point. After decades of corruption, ethnic manipulation, and policy paralysis, the people have given a clear mandate for systemic reform.

At this critical moment, Sri Lanka urgently needs structural reforms, particularly in education, which is the foundation of long-term national development, social mobility, and global competitiveness. Yet we observe that the very forces responsible for the country’s decline are once again attempting to block or derail reforms by exploiting religious, cultural, and emotional narratives.

We strongly affirm that no nation can be rebuilt through hatred, fear, or division. Education reform is not a political threat; it is a national necessity. Efforts to undermine reform through personal attacks and manufactured controversies serve only those who seek to return to power by keeping the country weak, divided, and intellectually impoverished.

Those who now attack Dr. Harini Amarasuriya are not defending culture or morality. They are defending privilege and political survival. Having failed the country for over seventy-five years through communalism, patronage, and anti-intellectualism, they now fear that an educated, critical, and empowered generation will render their outdated politics irrelevant.

This is why they target:

=a woman,

=an academic,

=and a reformer.

We therefore state clearly that we:

1. Condemn all forms of character assassination, gender-based attacks, and hate propaganda against the Prime Minister and Minister of Education.

2. Affirm our full support for Dr. Harini Amarasuriya’s leadership in advancing Sri Lanka’s education reforms.

3. Urge the government to proceed firmly and without retreat in implementing the proposed education reforms, in line with national policy and the public mandate.

4. Call upon academics, professionals, teachers, parents, and citizens to stand together against reactionary forces that seek to sabotage reform through fear mongering and disinformation.

A country cannot be rebuilt by those who destroyed it. A future cannot be created by those who fear education reforms.

Sri Lanka’s future must not be sacrificed for the ambitions of a few.Sri Lanka must move forward — with knowledge, dignity, and courage.

Signatories:

1. Markandu Thiruvathavooran, Attorney at law

2. S. Arivalzahan, University of Jaffna

3. Dr S.Ramesh, University of Jaffna

4. Dr. Mariadas Alfred, Former Dean, University of Peradeniya

5. Prof B.Nimalathasan, Senior Professor, University of Jaffna

6. S. Srivakeesan, Station Master, SriLankan Railways

7. A. T. Aravinthan, Branch Manager, Commercial Bank

8. Dr. S. Niththiyaruban, Paediatrician, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

9. Dr. S. Selvaganesh, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

10. Dr. S. Mathievaanan, Consultant Surgeon, Teaching Hospital, Jaffna

11. Prof. P. Iyngaran, University of Jaffna

12. Eng. M. Sooriasegaram, President, Education Development Consortium

13. Dr. S. Raviraj, Senior Consultant Surgeon, Former Dean, Faculty of Medicine, University, Jaffna.

14. Mr. Saminadan Wimal, University of Jaffna

15. Dr. A. Antonyrajan, University of Jaffna

16. P. Regno, Attorney at Law

17. Prof. J. Prince Jeyadevan, University of Jaffna

18. Prof. S. Muhunthan, University of Jaffna

19. Prof. R. Kapilan, University of Jaffna

20. Dr. S. Jeevasuthan, University of Jaffna

21. J.S. Thevaruban, University of Jaffna

22. S. Balaputhiran, University of Jaffna

23. Dr. N. Sivapalan, Retired Senior lecturer, University of Jaffna

24. I. P. Dhanushiyan, University of Jaffna

25. Dr. K. Thabotharan, University of Jaffna

26. Dr. Bahirathy J. Rasanen, University of Jaffna

27. Perinpanayagam Ronibus, Vice Secretary, Change Charitable Trust, Jaffna

28. Dr. S. Maheswaran, University of Peradeniya

29. Mr. S. Laleesan, Principal, Kopay Teachers’ College

30. Victor Antany, Teacher, Kilinochchi

31. K. Shanthakumar, Principal, Technical College, Vavuniya

32. S. Thirikaran, Principal, J/ Puttur Srisomaskanda College

33. Dr. T. Vannarajan, Advanced Technical Institute, Jaffna.

34. X. Don Bosco, Resource person, Piliyandala Educational Zone

35. K. Ravikumar, Regional Manager, Powerhands Pvt Ltd

36. Sathiyapriya Jeyaseelan, DO, Economist

37. A. Kalaichelvan, Chief Accountant, Animal Productive & Health

38. C. Vathanakumar, Retired Project Director

39. P. Kirupakaran, Department of Buildings (NP)

40. A. Antony Pilinton, David Peris Company, Jaffna

41. A. Muralietharan, Social Activist

42. Sinthuja Sritharan, Independent Researcher

43. T. Sritharan, Social Activist

44. Ms. Gnasakthi Sritharan, Social Activist

45. P. Thevatharsan, Management Service Officer

46. . S. Mohan, Social Activist

47. K. Jeyakumaran, Social Activist

48. Dr. N. Nithianandan, Chairman, Ratnam Foundation

49. George Antony Cristy, Social Activist

50. S. Thangarasa, Social Activist

51. N. Bhavan, Retd. Deputy Principal, Mahajana College

52. P. Muthulingam, Executive Director, Institute of Social Development, Kandy

53. M.K. Sivarajah, Social Activist

54. Mr. V. Sivalingam, Human Rights Activist

55. S. Jeyaganeshan, Samuthi Development Officer

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective