Features

THE WINTER ADVENTURE IN 16 COUNTRIES – Part “C”

CONFESSIONS OF A GLOBAL GYPSY

By Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

Founder & Administrator – Global Hospitality Forum

chandij@sympatico.ca

… Continuing from Wales, Ireland, France, Portugal and Spain …

Reaching Morocco in a small, old ship from Spain was exciting. It was the first time we had set foot in Africa, the second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia. Out of around 50 African countries in 1985 (today 54 countries) we were visiting just one. We did not notice the time passing during the four-hour voyage as we enjoyed the company of three university students travelling on the ship. Robert and Fritz were from West Germany, and their university colleague, Kalik was from Morocco. On their request, we changed our original plan to visit only Tangier, a port city in Morocco. We decided to travel with them from Tangier to Casablanca, where Kalik’s family lived. That was a good decision.

MOROCCO

During the time of modern history, Morocco’s strategic location near the mouth of the Mediterranean drew renewed European interest. In 1912, France and Spain divided Morocco into protectorates. Following intermittent riots and revolts against colonial rule, in 1956 Morocco regained its independence and reunified. The Kingdom of Morocco is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to the east, and the disputed territory of Western Sahara Dessert to the south. Morocco’s population in 1985 was 22 million.

Tangier

Tangier is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. Many civilisations and cultures have influenced the history of Tangier, starting from before the 10th century BC. Between the period of being a strategic Berber town and then a Phoenician trading centre to Morocco’s independence era, Tangier was a nexus for many cultures. In 1923, it was considered to have international status by foreign colonial powers and became a destination for many European and American diplomats, spies, bohemians, writers and businessmen. The population of Tangier in 1985 was around 350,000.

Our first impressions of Tangier were unpleasant. Moroccan custom officers were unfriendly and delayed us for over an hour. All our bags were thoroughly checked and we were interviewed one at a time. They were suspicious as my wife and I came to the customs barrier together with the three university students we met on the ship. After we were allowed to enter Morocco, we were then harassed by a pack of aggressive touts trying to sell us drugs. To escape from them, the five of us got into a taxi. After that we went on a tour visiting an exotic Sunday market and the colourful city centre.

We spent that night in a small guest house by the port and the next day, early in the morning, we took a train to Casablanca. During the five-hour train ride, Kalik showed off his talent in singing and Fritz joined in the singing providing us with some entertainment. I taught Robert to play Gin Rummy and my wife coached him to beat me. We passed some breath-taking scenery along the coast. We did not have time to explore the capital of the country, Rabat but were pleased to have a short train stop there. We reached Casablanca, the commercial capital and the largest city of Morocco with around 11% of the nation’s population, by mid-day.

Casablanca

From the main railway station, we took a taxi to Kalik’s brother’s house in the suburbs of Casablanca. We were warmly welcomed by his brother’s family which included his two wives. After some nice mint tea and welcome snacks, we left our bags in that house and commenced our city tour. Kalik was happy and proud to act as our unofficial tour guide of this historic city. He introduced us to a few of his childhood friends living in that neighbourhood. Two of Kalik’s brothers joined us and were excited to meet the four foreigners who had come to visit their humble home with their elder brother. It rained heavily, and Kalik’s brother Abdul said, “You bring our city good luck. It has not rained like this for five years!”

The sites we visited in this vibrant city had a unique blend of Moorish style and European culture, as French Art Deco effortlessly with classic Moroccan design. We explored impressive mosques, cathedrals and palaces. We also visited the bustling Marché Central and the sandy beaches of La Corniche. Old-fashioned buildings were sandwiched between mushrooming new buildings and bad roads with potholes. Casablanca reminded us of Colombo.

Immortalized in a classic World War II era movie which won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1942, Casablanca had always carried a romantic and intriguing mystique. However, with my efforts to find locations where the movie ‘Casablanca’ was filmed, I was disappointed to learn that it was shot entirely within California, mainly at Warner Bros. studios!

Casablanca is located on the Atlantic coast of the Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco. In 1985, the city had a population of about 2.5 million (today, after 37 years it has grown to 3.7 million). It is the eighth-largest city in the Arab world. Leading Moroccan companies and many international corporations doing business in the country have their headquarters and main industrial facilities in Casablanca. The port of Casablanca is one of the largest artificial ports in the world and is Morocco’s chief port. It also hosts the primary, naval base for the Royal Moroccan Navy.

Moroccan Lamb Stew with Couscous

On our second day in Casablanca, we were keen to taste authentic Moroccan food. Kalik became excited. “My mother makes the best lamb stew with couscous. She will cook it this evening for you at my parents’ home”, he announced to our delight. One of Morocco’s most famous dishes, it is a tasty, one-pot meal which has to be slow-cooked. It is based on cooked semolina wheat to which meat and/or vegetables are added. It is cooked in a clay pot, which is hermetically sealed with a cone-shaped lid. The result is a very savoury dish because spices and herbs such as cummin, turmeric, saffron, black pepper, parsley and ginger are added.

It is unclear when couscous originated. Some food historians believe that couscous originated millennia ago in the ancient kingdom of Numidia in present-day Algeria. The word couscous was first noted in early 17th century French, from Arabic kuskus. While many people today use a fork or spoon to eat couscous, traditionally couscous is eaten with the fingers which we were prepared to do. Our two West German friends were not so sure about that, particularly when all our portions were served on one, large plate.

Kalik’s mother, Salma spoke very little English. When she heard that I was an executive chef some years ago, she was a bit nervous but soon commenced to demonstrate her cooking method to me step by step. Kalik’s duties were expanded to become an interpreter, as well. Another middle-age Moroccan lady was helping Salma with the cooking. As they were laughing and behaving like best friends, I inquired if they were sisters. Kalik hugged that other lady and said, “This is Nora, my second mother.” As we looked confused, he clarified, “Nora is my father’s second wife.”

The aroma from Salma’s dish was amazing. The saffron she had added created a strong, leathery and earthy aroma. We were impatiently waiting around a large round table to have our dinner but none of the ladies in the family sat with us. As Kalik’s father was out of town on business, Kalik acted as the head of the family in hosting us. The authentic hospitality Salma and Nora and their daughters provided was outstanding. They simply wanted us to enjoy their food, company and home. “The main ingredient in our cooking is love!” Salma told us in her broken-English. She was correct.

After dinner we were invited to stay in their house. Considering that they had eleven members of the family living in the three-roomed house, we politely declined. Kalik’s brother arranged accommodations for us in a nearby inn. Salma and Nora were too shy to pose for a group photograph with us, but eight of their children, including very, pretty teenage sisters of Kalik joined us after some gentle persuasion. They giggled the whole time.

After checking into the nearby inn for the night, we heard a loud noise from the adjoining room given to our West German friends. We heard Fritz, screaming at Robert in German, using some bad words. He was saying, “Surely I cannot use this f***ing toilet!” It was a culture shock. Squat toilets are found throughout Africa and are especially common in Muslim countries like Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. Essentially, they are holes in the ground equipped with a pan to sit on, rather than the seat and bowl of Western toilet systems.

THE WINTER …

Leaving Africa

Leaving Africa I became keen to explore this continent further. After a lapse of 14 years, I eventually returned to Africa in 1999 to explore Egypt briefly during a honeymoon cruise in the Mediterranean. In 2000 I was offered the position of the General Manager of the 700-room Le Meridien Red Sea in Egypt, an offer I did not accept, to pursue my second career as a university professor. In 2004 and 2005 I was fortunate to get opportunities to visit Africa for long trips on three occasions. I visited South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria and Botswana for work combined with leisure. My experiences and some adventures during these trips will be narrated in future episodes of this column.

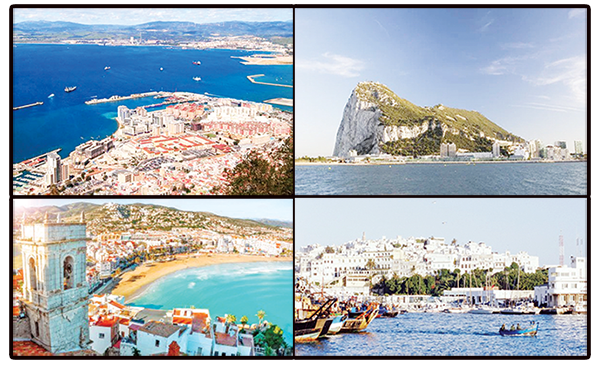

Passing Gibraltar

Although we did not enter Gibraltar, a British Overseas Territory and city located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, we were pleased that our ship from Africa to Europe sailed very close to the rock of Gibraltar. It has an area of only 2.6 square miles and is bordered to the north by Spain. The landscape is dominated by the Rock of Gibraltar at the foot of which is a densely populated town area, home to over 29,000 people, primarily Gibraltans.

BACK TO SPAIN

Algeciras

When returning to the Port of Algeciras we realized that it is one of the largest ports in Europe and the world in terms of containers, cargo and transshipment. Algeciras is principally a transport hub and industrial city. It serves as the main embarkation point between Spain and Tangier and other ports in Morocco as well as the Canary Islands and the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. It is ranked as the 16th busiest port in the world.

The city also has a substantial fishing industry and exports a range of agricultural products from the surrounding area, including cereals, tobacco and farm animals. Gradually it was becoming a significant tourist destination, with popular day trips to Tarifa to see bird migrations; to Gibraltar to see the territory’s sights and culture; and to the Bay of Gibraltar for whale watching excursions. We boarded another night train to reach Valencia.

Valencia

Valencia is the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 750,000 inhabitants in 1985. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It is one of the major urban areas on the European side of the Mediterranean Sea. Valencia was founded as a Roman colony in 138 BC. Islamic rule and acculturation ensued in the 8th century. After a Christian conquest in the 13th century, the city became the capital of the Kingdom of Valencia.

The city’s port is the fifth busiest container port in Europe and the busiest container port on the Mediterranean Sea. Valencia is famous for the City of Arts and Sciences, the Valencia Cathedral, the Old Town, the Central Market, and as the birthplace of paella. As recommended by a Spanish couple in our train, we decided to taste the authentic Valencian paella during our short visit. One of the most well-known Spanish dishes abroad, paella originated in Valencia.

While watching the chef of a small café cook the paella in a large, flat pan with chicken and rabbit, we made a quick request. We preferred he did not include rabbit in our dish but he was not happy. “Rabbit is an essential item in Paella Valenciana” the chef grumbled, but changed his recipe specifically for us. I observed his cooking method closely. After browning the pieces of chicken in olive oil, he added green beans (originating from Valencia), Garrofón butter beans, tomato, saffron and water. Rice was the last ingredient added to the reduced broth. The most commonly used rice in paella in Spain is called Bomba. It’s a short-grain rice cultivated in the eastern parts of Spain. It absorbs liquid very well, but stays quite firm during the cooking process. It is often referred to as paella rice.

Barcelona

I loved Barcelona, as it is very rich in art and architecture. The fantastical Sagrada Família church and other modernist landmarks designed by Antoni Gaudí dot the city. Museum Picasso and Fundació Joan Miró feature modern art by their namesakes. The City History Museum with several Roman archaeological sites, enhance the value of this great destination. Founded as a Roman city in the Middle Ages, Barcelona became the capital of the County of Barcelona. It was wrested from Arab domination by the Catalans, in the late 15th century. Barcelona has a rich, cultural heritage and is today an important cultural centre and a major tourist destination.

As I was getting ready to explore the city on our second and last day of the stay, we had to suddenly change our plans. My wife had taken ill and was shivering with a very high fever. The lady who owned the guest house we stayed in the middle of Barcelona was very kind and helpful. At age 24, my wife was the same age as the guest house owner’s daughter. She prohibited us from travelling further until my wife had recovered fully. I realized that my plan was too structured and too ambitious. We took a break and stayed in Barcelona for four days. I changed my role from an adventurous traveller to a care-giver.

guest house owner’s daughter. She prohibited us from travelling further until my wife had recovered fully. I realized that my plan was too structured and too ambitious. We took a break and stayed in Barcelona for four days. I changed my role from an adventurous traveller to a care-giver.

Will continue in next week’s article: THE WINTER ADVENTURE IN 16 COUNTRIES – Part “D”,

with adventures in France, Italy, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria and in the boarder to Romania …

Features

A long-running identity conflict flares into full-blown war

It was Iran’s first spiritual head of state, the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who singled out and castigated the US as the ‘Great Satan’ in the revolutionary turmoil of the late seventies of the last century that ushered in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The core issue driving the long-running confrontation between Islamic Iran and the West has been religious identity and the seasoned observer cannot be faulted for seeing the explosive emergence of the current war in the Middle East as having the elements of a religious conflict.

It was Iran’s first spiritual head of state, the late Ayatollah Khomeini, who singled out and castigated the US as the ‘Great Satan’ in the revolutionary turmoil of the late seventies of the last century that ushered in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The core issue driving the long-running confrontation between Islamic Iran and the West has been religious identity and the seasoned observer cannot be faulted for seeing the explosive emergence of the current war in the Middle East as having the elements of a religious conflict.

The current crisis in the Middle East which was triggered off by the recent killing of Iranian spiritual head of state Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in a combined US-Israel military strike is multi-dimensional and highly complex in nature but when the history of relations between Islamic Iran and the West, read the US, is focused on the religious substratum in the conflict cannot be glossed over.

In fact it is not by accident that US President Donald Trump resorts to Biblical language when describing Iran in his denunciations of the latter. Iran, from Trump’s viewpoint, is a primordial source of ‘evil’ and if the Middle East has collapsed into a full-blown regional war today it is because of the ‘evil’ influence and doings of Iran; so runs Trump’s narrative. It is a language that stands on par with that used by the architects of the Iranian revolution in the crucial seventies decade.

In other words, it is a conflict between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ and who is ‘good’ and who is ‘evil’ in the confrontation is determined mainly by the observer’s partialities and loyalties which may not be entirely political in kind. It should not be forgotten that one of President Trump’s support bases is the Christian Right in the US and in the rest of the West and the Trump administration’s policy outlook and actions should not be divorced from the needs of this segment of supporters to be fully made sense of.

The reasons for the strong policy tie-up between Rightist administrations in the US in particular and Israel could be better comprehended when the above religious backdrop is taken into consideration. Israel is the principal actor in the ‘Old Testament’ of the Bible and is seen as ‘the Chosen People of God’ and this characterization of Israel ought to explain the partialities of the Republican Right in particular towards Israel. Among other things, this partiality accounts for the strong defence of Israel by the US.

For the purposes of clarity it needs to be mentioned here that the Bible consists of two parts, an ‘Old’ and ‘New Testament’ , and that the ‘New Testament’ or ‘Message’ embodies the teachings of Jesus Christ and the latter teachings are seen as completing and in a sense giving greater substance to the ‘Old Testament’. However, Judaism is based mainly on ‘Old Testament’ teachings and Judaism is distinct from Christianity.

To be sure, the above theological explanation does not exhaust all the reasons for the war in the Middle East but the observer will be allowing an important dimension to the war to slip past if its importance is underestimated.

It is not sufficiently realized that the Iranian Islamic Revolution of 1979 utterly changed international politics and re-wrote as it were the basic parameters that must be brought to bear in understanding it. So important is the Islamic factor in contemporary world politics that it helped define to a considerable degree the new international political order that came into existence with the collapsing of the Cold War and the disintegration of the USSR .

Since the latter developments ‘political Islam’ could be seen as a chief shaping influence of international politics. For example, it accounts considerably for the 9/11 calamity that led to the emergence of fresh polarities in world politics and ushered in political terrorism of a most destructive kind that is today disquietingly visible the world over.

It does not follow from the foregoing that Islam, correctly understood, inspires terrorism of any kind. Islam proclaims peace but some of its adherents with political aims interpret the religion in misleading, divisive ways that run contrary to the peaceful intents of the faith. This is a matter of the first importance that sincere adherents of the faith need to address.

However, there is no denying that the Islamic Revolution in Iran of 1979 has been over the past decades a great shaper of international politics and needs to be seen as such by those sections that are desirous of changing the course of the world for the better. The revolution’s importance is such that it led to US political scientist Dr. Samuel P. Huntingdon to formulate his historic thesis that a ‘Clash of Civilizations’ is upon the world currently.

If the above thesis is to be adopted in comprehending the principal trends in contemporary world politics it could be said that Islam, misleadingly interpreted by some, is pitting a good part of the Southern hemisphere against the West, which is also misleadingly seen by some, as homogeneously Christian in orientation. Whereas, the truth is otherwise. The West is not necessarily entirely synonymous with Christianity, correctly understood.

Right now, what is immediately needed in the Middle East is a ceasefire, followed up by a negotiated peace based on humanistic principles. Turning ‘Spears into Ploughshares’ is a long gestation project but the warring sides should pay considerable attention to former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami’s memorable thesis that the world needs to transition from a ‘Clash of Civilizations’ to a ‘Dialogue of Civilizations’. Hopefully, there would emerge from the main divides leaders who could courageously take up the latter challenge.

It ought to be plain to see that the current regional war in the Middle East is jeopardising the best interests of the totality of publics. Those Americans who are for peace need to not only stand up and be counted but bring pressure on the Trump administration to make peace and not continue on the present destructive course that will render the world a far more dangerous place than it is now.

In the Middle East region a durable peace could be ushered if only the just needs of all sides to the conflict are constructively considered. The Palestinians and Arabs have their needs, so does Israel. It cannot be stressed enough that unless and until the security needs of the latter are met there could be no enduring peace in the Middle East.

Features

The art and science of communicating with your little child

The two input gateways of communication, sight and sound, are quite well developed at birth. In fact, the auditory system becomes functional around 24 weeks in the womb, and the normal newborn can hear quite well after birth. However, the newborn’s vision is a little blurry at birth, and the baby sees the world in shades of grey, while being able only to focus on things 20 to 30 cm (8–12 inches) away. Coincidentally, this is perhaps the exact distance to a mother’s face during breastfeeding. By 2-3 months, there are colour vision capabilities and the ability to track. By 5-8 months, there is depth perception, and by 12 months, there is adult clarity of vision.

By the time a child turns five, his or her brain has already reached 90% of its adult size. This astonishing physical growth is not just happening on its own; it is, to a certain extent, fuelled by experience, and the most vital experience a young child can have is communication with his or her parents.

Modern developmental neuroscience has shifted our understanding of how children learn. We used to think babies were passive sponges, slowly absorbing the world. We now know they are active characters from day one, constantly seeking interaction to build the architecture of their minds. This architecture is not built by apps, vocabulary flashcards, or educational television. It is built through simple, loving, back-and-forth interactions with anyone they come across, but mostly their parents.

The Foundation: Serve and Return (0–12 Months)

Communication with an infant from birth to one year of age begins long before they speak their first word. In the first year, the goal is to master a phenomenon called Serve and Return. This is a basic scenario picked up from the game of tennis. At the start of each game of a set in tennis, a player serves, and the opponent returns the serve. Just imagine a tennis match, where a baby “serves” by making a sound, making eye contact, reaching for a toy, or crying. The job of anyone in the vicinity, who very often are the parents of the baby, is to “return” the ball. If they babble, you babble back. If they point at a cat, you look and say, “Yes, that’s a furry cat!” This simple act does two things. The first is Brain Building, which creates and strengthens neural pathways in the language and emotional centres of the brain. The other is Emotional Security, a thing which teaches a baby that he or she has some help in the learning processes. The baby absorbs the notion that when he or she signals a need, his or her world will respond. This forms the basis of a secure attachment. Scientists have advocated that during this stage, people, especially the parents of a baby, should embrace what is called ‘parentese’. It is the use of a somewhat high-pitched, exaggerated voice. Research has shown that babies pay more attention to parentese than to regular adult speech, helping them to map the sounds of their native language more quickly.

The Language Explosion: Toddlers (1–3 Years)

When a child starts speaking words, the game changes considerably and quite profoundly. This period is defined by a rapid increase in his or her vocabulary and the beginning of grammar. It is very important to narrate everything. The people around, especially the parents, need to become kind of sports commentators for your life. While dressing them, one could say, “First we put on the red sock. After that, we put the other red sock on your left foot.” What we are doing by this is to give them the labels for the world they see.

It is also important to expand, but not truly correct, whatever the child says. If a toddler points to a car and says “Car!”, don’t just say “Yes.” Expand on it: “Yes, that is a big, fast, red car!” You are adding a new vocabulary and grammatical structure through a natural process. If the child says “Me go,” respond with, “Yes, you are going!” rather than correcting and saying “No…, you should say ‘I am going’.”

Toddlers love reading the same book, even one hundred times. While it may be tedious for those around the baby, it is important to realise that such repetition is vital for their learning. They are predicting what comes next, which is a core cognitive skill.

The Preschooler: Building Stories and Logic (3–5 Years)

By age three, the focus shifts from “what” to “why.” Preschoolers are beginning to understand complex emotions, time, and causality. This is the age at which it is best to ask questions which require thought and understanding. Such indirect open-ended questions would sound like “What was the best part of the park today?” or “How do you think that character in the story is feeling?“

A preschooler’s world is full of “big feelings” they cannot yet manage. When they are upset because they cannot have a cookie, avoid saying “Don’t cry over nothing.” Instead, name the emotion: “Don’t cry, you can have a cookie after dinner“. This teaches them emotional literacy. Parents and others around in the home could share stories about when they were little, or make up fantasy tales together. Storytelling teaches sequential logic (beginning, middle, end) and strengthens their imagination.

The Absolute Master Class: Learning Through Play

If communication is the fuel for brain development, play is the engine. For a child under five, play is not a break from learning; play is learning. It is how they explore physics (stacking blocks), mathematics (sorting shapes), social dynamics (sharing toys), and language (pretend play). We can boost their development exponentially by weaving communication into their play.

When a child is playing with blocks, dough, or puzzles, they are building fine motor skills and spatial awareness. It is also useful to use three-dimensional words: “Can you put the blue block on top of the red one?” “The puzzle piece is next to your knee.” One could also ask them to describe the texture: “Is the dough soft or hard?“

Pretend play, such as acting as a doctor, an engineer, a chef, or a superhero, is one of the most cognitively demanding things a child can do. It requires them to understand symbolic thought and to take on another person’s perspective. Join their world as a supporting character, not the director. If they are the doctor, ask, “Doctor, my teddy bear’s tummy hurts. What should I do?” This encourages them to use vocabulary relevant to the scenario and practice complex social problem-solving.

Playing with water, sand, slime, or safe food products allows children to process sensory information. This is the perfect time for descriptive vocabulary. Use contrasting words: wet/dry, hot/cold, sticky/smooth, loud/quiet.

A few special words for parents. You do not need an expensive degree or specialised toys to build your child’s brain. The most powerful tool you have is your own responsiveness. Modern science tells us that the basic recipe for a thriving child is simple: Look at them when they signal you. Respond with warmth and words. Narrate their world and Join their play.

You are not just talking to your child; you are building his or her future, even via just one conversation at a time. So, go on talking to your child and even make him or her a real-life chatterbox.

Dr B. J. C. Perera

Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Features

Promoting our beauty and culture to the world

Tourism is very much in the news these days and it’s certainly a good sign to see lots of foreigners checking out Sri Lanka.

Tourism is very much in the news these days and it’s certainly a good sign to see lots of foreigners checking out Sri Lanka.

With this in mind, Ruki’s Model Academy & Agency recently had a spectacular event to select Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka in order to promote Sri Lanka in the international scene.

Nimesha Premachandra was crowned Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026.

She says she owes her success to Ruki (Rukmal Senanayake), the National Director and model trainer, and personality and advocacy trainer Tharaka Gurukanda.

Nimesha is a school teacher by profession, an actress and TV presenter by passion, and an entrepreneur by spirit.

She believes in balancing grace with purpose, and using her platform to inspire women, while promoting the beauty and culture of Sri Lanka to the world. And this is how our Chit-Chat went:

Nimesha Premachandra: Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026

01. How would you describe yourself?

I am a passionate, disciplined, and people-oriented person. I love learning, performing, and guiding others, especially young minds, through education.

02. If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?

I would probably try to be less self-critical and allow myself to celebrate achievements more often.

03. If you could change one thing about your family, what would it be?

Nothing major. I am grateful for my family’s love and support, which has shaped who I am today.

04. Is Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka your very first pageant?

No. I have been part of pageants before, but Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka is very special because it represents purpose, culture, and global representation.

05. What made you take part in this contest?

I wanted to represent Sri Lanka internationally and use this platform to promote tourism, culture, and women’s empowerment.

06. Obviously, you must be excited about participating in the grand finale, in Vietnam; any special plans for this big event?

Yes, I am extremely excited. My focus is to showcase Sri Lankan elegance, hospitality, and authenticity, while building meaningful connections with participants from around the world.

07. How do you intend promoting tourism, in Sri Lanka, during your rein?

I plan to highlight Sri Lanka’s diverse experiences in culture, heritage, wellness, nature, and local hospitality through media appearances, digital storytelling, and tourism collaborations.

08. School?

Kaluthara Balika. School life played a big role in shaping me. I actively participated in sports and performing arts, which later helped me build confidence as an actress and presenter.

09. Happiest moment?

Being crowned Mrs. Tourism Sri Lanka 2026 and seeing the pride in my family’s eyes – definitely one of my happiest moments.

10. What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Peace of mind, good health, and being surrounded by the people I love while doing work that has meaning.

11. Which living person do you most admire?

I most admire Angelina Jolie because she beautifully balances her work as an actress with meaningful humanitarian efforts. She uses her global platform to support refugees, advocate for human rights, and inspire women to be strong, compassionate, and independent.

12. Which is your most treasured possession?

My memories and experiences because they remind me how far I’ve come, and keep me grounded.

13. Your most embarrassing moment?

Like everyone, I’ve had small on-stage mishaps, but they always taught me to laugh at myself and move forward confidently.

14. Done anything daring?

Participating in pageants while balancing teaching, media work, and family life has been one of the boldest and most rewarding decisions I’ve made.

Keen to use her title to promote Sri Lanka globally

15. Your ideal vacation?

A peaceful destination surrounded by nature; somewhere I can relax, reconnect, and experience local culture.

16. What kind of music are you into?

I enjoy soft, soulful music because it helps me relax and stay inspired.

17. Favourite radio station:

I enjoy stations that blend good music with meaningful conversation and positive energy.

18. Favourite TV station:

Sri Lanka Rupavahini Corporation. It’s where it all began for me. It played a significant role in my journey as a TV presenter and helped shape my confidence and passion for media.

19 What would you like to be born as in your next life?

Someone who continues to inspire others because making a positive impact is what matters most.

20. Any major plans for the future?

I hope to expand my work in media and entrepreneurship while continuing my role as an educator and using my title to promote Sri Lanka globally.

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAn efficacious strategy to boost exports of Sri Lanka in medium term

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSri Lanka to Host First-Ever World Congress on Snakes in Landmark Scientific Milestone

-

Features3 days ago

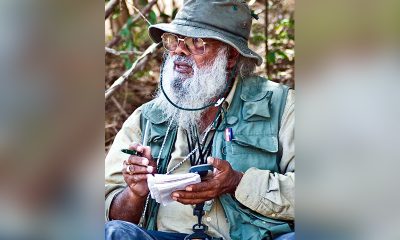

Features3 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul