Opinion

The useful and the useless

“All art is useless, because its aim is simply to create a mood” – Oscar Wilde

By Prof. Kirthi Tennakone

ktenna@yahoo.co.uk

Today, our society focuses its attention solely on useful things, leading to material and monetary gains, envisaged advantages, or accomplishing plans. The work we do at home, in the workplace or at school, the policies we frame and the social activities we engage in are primarily intended for that purpose. And we subscribe to charity and alms, expecting dividends in a life after death.

We rarely go beyond the routine and the system discourages such deviations. We are reluctant to embark on seemingly useless and unprofitable things and fear undertaking challenges.

When children play and meddle, parents tell them all this is useless fooling, go and follow your lessons. When they struggle to secure a job after finishing school, the same parents would remark, all they had learned in school is useless.

Education pundits accredit unemployment and the absence of innovation in the country to useless subjects in the curriculum and propose reforms.

Despite the crazy emphasis on utility, we remain weak in performing useful tasks and producing useful goods.

Are we on the wrong track? History tells us embarking on outwardly useless things is indeed the secret behind transformative innovations and human intellectual advancement.

In 1872, an unassuming lad named Paul Ehrlich entered the Medical School in Strassburg, Germany. One day, in anatomy class, instead of dissecting corpses as instructed, he was coloring human tissue and looking at them through a microscope.

When the professor asked him what he was doing; he replied, ‘I am fooling’. The professor, without pulling him up said, ‘Continue your fooling’. Facing many hurdles because of his attitude, Ehrlich completed his medical degree. The faculty noted he is an unusually talented person and would not choose to practice as a doctor. As expected, he continued research making groundbreaking discoveries. Paul Ehrlich is regarded as the father of pharmaceutical science and chemotherapy. He was the first to introduce the far-reaching hypothesis that chemical substances can be synthesized, which when delivered to the body combat disease. Ehrlich earned the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1908.

The above story and many other similar anecdotes were cited by the American educator, Abraham Flexner in his book “The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge “. Flexner, who began his career in 1903 as a teacher in elementary school with a bachelor’s degree in classics, later turned out to be a vociferous critic of higher education in the United States, especially medicine. He pointed out that the standard of medical education needs to be elevated making it rigorously science -based. He vehemently opposed the provision of research funding to universities and research institutions considering only the utility value, pointing out curiosity- driven investigations, believed to be useless by many, were the ones that transformed the world. He worked hard to establish the Institute of Advanced Study, Princeton and served as its first director. Flexner was instrumental in inviting Albert Einstein and several other European scientists and mathematicians to the Institute.

From time to time, people of the highest intellectual acclaim have reminded the world of the virtue of pursuing novel things ostensibly useless.

George Fitzgerald, an eminent Irish physicist who made important contributions to the science of radio wave propagation, wrote a letter to the Editor of the Journal, Nature in 1892, titled “The value of useless studies”, where he stated, “If universities do not study useless subjects, who will?” Once a subject becomes useful, it may very well be left to schools and technical colleges.”

In his analysis of social issues, Karl Marx declared, “Production of too many useful things results in too many useless people. The improvements in the quality of life in relation to technological advancement prove his assertion is not entirely correct. Yet what Marx said warns humanity of the repercussions of useful innovations.

Smartphones are undoubtedly useful. However, the youngsters addicted to them may perform poorly, because they interfere with the natural process of learning via healthy environmental and social interaction. The same applies to innovations in AI. Students who use chatbots for writing essays and solving mathematical problems, get deprived of the essential brain exercise needed to become more useful – you are being useful to yourself and to society.

In the present-day context, it would be more appropriate to say: “The engagement in useful things all the time decreases our usefulness”.

The usefulness and uselessness have crept into our education and planning more than any other sector. Until about three decades after independence, education philosophy in general was more balanced, emphasizing both arts and science. Later, the arts got branded as useless and science useful.

Oscar Wilde, one of the greatest artists (playwright and poet) once said “All arts is quite useless”. When someone asked him what he really meant, he replied, “Art is useless because its aim is simply to create a mood. It is not meant to instruct, or influence action in any way. It is superbly sterile, and the note of its pleasure is sterility.” The usefulness of the arts is their practical uselessness!

A good mood arouses emotion, serenity, imagination, and empathy, qualities even more useful than most useful material things. Our failure to inculcate these qualities resulted in rampant corruption seen everywhere. And other weaknesses, including our lag in delivering innovations, because the above qualities foster creativity and the spirit of inventiveness. A trait common to men and women who led the way for modern utilities, we enjoy!

Years ago, a team self-appointed to make suggestions to revise the A-level curriculum identified several subjects as redundant and useless. Among them were physics and Sanskrit. They also recommended a pass in physics should not be a requirement to enter medical schools in our country. The author commented that Sanskrit is deeply inbuilt to our culture, quoting the Indian physicist CV Raman, who said, “It is wrong to say Sanskrit is dead; it is very much alive, and it embodies everything we call ours. And

if a pass in A-level physics is made non-compulsory to enter medical schools, patients should be cautious in visiting doctors without a pass in this subject”.

In education and research, we are inclined heavily towards practical aspects, believing theory would not help, but in vain we continue to be poor in original, practically useful ideas and their implementation.

A technology stream was added to A-level, claiming physical and bioscience courses are theory- biased and not conducive to practical work. However, the real problem of the GCE A/L science students is they are deficient in theory. And for that reason, they cannot adapt to innovations. What they learn, mainly from tuition classes, are methods of answering questions in a disconnected approach. The coherence of theories and their value in foreseeing innovations is not emphasized.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519), one of the greatest innovative minds of all time said: “He who loves practice without theory is like a sailor who boards ships without a rudder and compass and never knows where he may cast”. He made this statement when scientific theories were not as ripe as today to make predictions and envisage innovations. Though not implemented, the basic science policy drafted by the National Science and

Technology Commission (NSTEC) highlights the value of basic science and theory, stating: “Basic science is the study aimed towards the advancement of scientific theories for the understanding of natural phenomena and/or making predictions. It is an integral part of all development programs. For any country, the creation of a strong foundation in basic scientific research is a prerequisite for applied research, innovations, and economic growth. There cannot be applied research or innovations without basic research. Curiosity-driven basic research influences all human endeavors, including rational thinking. The benefits of basic science research are gained through the dissemination of fundamental knowledge and principles of science”.

Universities are free to do either useful or useless research and teach disciplines belonging to both domains – permitting teachers and students to be critical and dream. Unfortunately, our universities tend to focus on applied aspects, neglecting the basics, theory, and arts. Nevertheless, no signs of increased productivity, and students turning more conventional or ideological than critical.

Strangely, the Institute of Fundamental Studies, established exclusively to promote basic science and theoretical studies has taken a retrograde step grossly deviating from its mandate and entertaining practical projects best carried out elsewhere without duplications. Sri Lanka is full of untapped exceptional talent. Allowing and providing opportunities for our younger scientists to pursue truly fundamental research would foster science and technology in this country.

We need to be exemplary as the professor who supervised Paul Erlich. Recognizing talent and potential, he permitted Ehrlich to play aimlessly in the anatomy lab. When new scientific and technological fashions originate abroad, we rush to pick them up expecting immediate economic gains. Earlier, it was biotechnology, then nanotechnology and today, AI. To reap the fruits of these trends and create our own fashions, we need minds turned sophisticated by doing useless things as well. Munidasa Kumaratunga said a nation that does not create will not rise. Creations often originate from indulgence in activities seemingly useless.

Opinion

Capt. Dinham Suhood flies West

A few days ago, we heard the sad news of the passing on of Capt. Dinham Suhood. Born in 1929, he was the last surviving Air Ceylon Captain from the ‘old guard’.

He studied at St Joseph’s College, Colombo 10. He had his flying training in 1949 in Sydney, Australia and then joined Air Ceylon in late 1957. There he flew the DC3 (Dakota), HS748 (Avro), Nord 262 and the HS 121 (Trident).

I remember how he lent his large collection of ‘Airfix’ plastic aircraft models built to scale at S. Thomas’ College, exhibitions. That really inspired us schoolboys.

In 1971 he flew for a Singaporean Millionaire, a BAC One-Eleven and then later joined Air Siam where he flew Boeing B707 and the B747 before retiring and migrating to Australia in 1975.

Some of my captains had flown with him as First Officers. He was reputed to have been a true professional and always helpful to his colleagues.

He was an accomplished pianist and good dancer.

He passed on a few days short of his 97th birthday, after a brief illness.

May his soul rest in peace!

To fly west my friend is a test we must all take for a final check

Capt. Gihan A Fernando

RCyAF/ SLAF, Air Ceylon, Air Lanka, Singapore Airlines, SriLankan Airlines

Opinion

Global warming here to stay

The cause of global warming, they claim, is due to ever increasing levels of CO2. This is a by-product of burning fossil fuels like oil and gas, and of course coal. Environmentalists and other ‘green’ activists are worried about rising world atmospheric levels of CO2. Now they want to stop the whole world from burning fossil fuels, especially people who use cars powered by petrol and diesel oil, because burning petrol and oil are a major source of CO2 pollution. They are bringing forward the fateful day when oil and gas are scarce and can no longer be found and we have no choice but to travel by electricity-driven cars – or go by foot. They say we must save energy now, by walking and save the planet’s atmosphere.

THE DEMON COAL

But it is coal, above all, that is hated most by the ‘green’ lobby. It is coal that is first on their list for targeting above all the other fossil fuels. The eminently logical reason is that coal is the dirtiest polluter of all. In addition to adding CO2 to the atmosphere, it pollutes the air we breathe with fine particles of ash and poisonous chemicals which also make us ill. And some claim that coal-fired power stations produce more harmful radiation than an atomic reactor.

STOP THE COAL!

Halting the use of coal for generating electricity is a priority for them. It is an action high on the Green party list.

However, no-one talks of what we can use to fill the energy gap left by coal. Some experts publicly claim that unfortunately, energy from wind or solar panels, will not be enough and cannot satisfy our demand for instant power at all times of the day or night at a reasonable price.

THE ALTERNATIVES

It seems to be a taboo to talk about energy from nuclear power, but this is misguided. Going nuclear offers tried and tested alternatives to coal. The West has got generating energy from uranium down to a fine art, but it does involve some potentially dangerous problems, which are overcome by powerful engineering designs which then must be operated safely. But an additional factor when using URANIUM is that it produces long term radioactive waste. Relocating and storage of this waste is expensive and is a big problem.

Russia in November 2020, very kindly offered to help us with this continuous generating problem by offering standard Uranium modules for generating power. They offered to handle all aspects of the fuel cycle and its disposal. In hindsight this would have been an unbelievable bargain. It can be assumed that we could have also used Russian expertise in solving the power distribution flows throughout the grid.

THORIUM

But thankfully we are blessed with a second nuclear choice – that of the mildly radioactive THORIUM, a much cheaper and safer solution to our energy needs.

News last month (January 2026) told us of how China has built a container ship that can run on Thorium for ten years without refuelling. They must have solved the corrosion problem of the main fluoride mixing container walls. China has rare earths and can use AI computers to solve their metallurgical problems – fast!

Nevertheless, Russia can equally offer Sri Lanka Thorium- powered generating stations. Here the benefits are even more obviously evident. Thorium can be a quite cheap source of energy using locally mined material plus, so importantly, the radioactive waste remains dangerous for only a few hundred years, unlike uranium waste.

Because they are relatively small, only the size of a semi-detached house, such thorium generating stations can be located near the point of use, reducing the need for UNSIGHTLY towers and power grid distribution lines.

The design and supply of standard Thorium reactor machines may be more expensive but can be obtained from Russia itself, or China – our friends in our time of need.

Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

Will computers ever be intelligent?

The Island has recently published various articles on AI, and they are thought-provoking. This article is based on a paper I presented at a London University seminar, 22 years ago.

Will computers ever be intelligent? This question is controversial and crucial and, above all, difficult to answer. As a scientist and student of philosophy, how am I going to answer this question is a problem. In my opinion this cannot be purely a philosophical question. It involves science, especially the new branch of science called “The Artificial Intelligence”. I shall endeavour to answer this question cautiously.

Philosophers do not collect empirical evidence unlike scientists. They only use their own minds and try to figure out the way the world is. Empirical scientists collect data, repeat and predict the behaviour of matter and analyse them.

We can see that the question—”Will computers ever be intelligent?”—comes under the branch of philosophy known as Philosophy of Mind. Although philosophy of mind is a broad area, I am concentrating here mainly on the question of consciousness. Without consciousness there is no intelligence. While they often coincide in humans and animals, they can exist independently, especially in AI, which can be highly intelligent without being conscious.

AI and philosophers

It appears that Artificial Intelligence holds a special attraction for philosophers. I am not surprised about this as Al involves using computers to solve problems that seem to require human reasoning. Apart from solving complicated mathematical problems it can understand natural language. Computers do not “understand” human language in the human sense of comprehension; rather, they use Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning to analyse patterns in data. Artificial Intelligence experts claim certain programmes can have the possibility of not only thinking like humans but also understanding concepts and becoming conscious.

The study of the possible intelligence of logical machines makes a wonderful test case for the debate between mind and brain. This debate has been going on for the last two and a half centuries. If material things, made up entirely of logical processes, can do exactly what the brain can, the question is whether the mind is material or immaterial.

Although the common belief is that philosophers think for the sake of thinking, it is not necessarily so. Early part of the 20th century brought about advances in logic and analytical philosophy in Britain. It was a philosopher (Ludwig Wittgenstein) who invented the truth table. This was a simple analytic tool useful in his early work. But this was absolutely essential to the conceptual basis of early computer science. Computer science and brain science have developed together and that is why the challenge of the thinking machine is so important for the philosophy of mind. My argument so far has been to justify how and why AI is important to philosophers and vice versa.

Looking at computers now, we can see that the more sophisticated the computer, the more it is able to emulate rather than stimulate our thought processes. Every time the neuroscientists discover the workings of the brain, they try to mimic brain activity with machines.

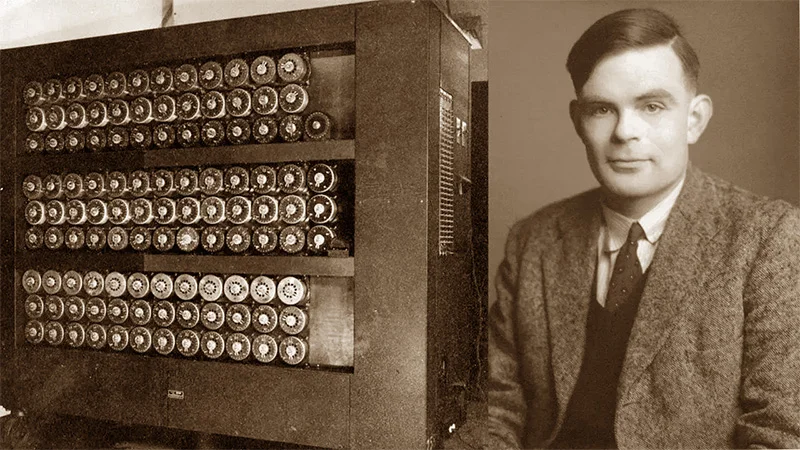

How can one tell if a computer is intelligent? We can ask it some questions or set a test and study its response and satisfy ourselves that there is some form of intelligence inside this box. Let us look at the famous Alan Turing Test. Imagine a person sitting at a terminal (A) typing questions. This terminal is connected to two other machines, (B) and (C). At terminal (B) sits another person (B) typing responses to the questions from person (A). (C) is not a human being, but a computer programmed to respond to the questions. If person (A) cannot tell the difference between person (B) and computer(C), then we can deduce that computer is as intelligent as person (B). Critics of this test think that there is nothing brilliant about it. As this is a pragmatic exercise and one need not have to define intelligence here. This must have amused the scientists and the philosophers in the early days of the computers. Nowadays, computers can do much more sophisticated work.

Chinese Room experiment

The other famous experiment is John Sealer’s Chinese room experiment. *He uses this experiment to debunk the idea that computers could be intelligent. For Searle, the mind and the brain are the same. But he warns us that we should not get carried away with the emulative success of the machines as mind contains an irreducible subjective quality. He claims that consciousness is a biological process. It is found in humans as well as in certain animals. It is interesting to note that he believes that the mind is entirely contained in the brain. And the empirical discovery of neural processes cannot be applied to outside the brain. He discards mind-body dualism and thinks that we cannot build a brain outside the body. More commonly, we believe the mind is totally in the brain, and all firing together and between, and what we call ‘thought’ comes from their multifarious collaboration.

Patricia and Paul Churchland are keen on neuroscientific methods rather than conventional psychology. They argue that the brain is really a processing machine in action. It is an amazing organ with a delicately organic structure. It is an example of a computer from the future and that at present we can only dream of approaching its processing speed. I think this is not something to be surprised about. The speed of the computer doubles every year and a half and in the distant future there will be machines computing faster than human beings. Further, the Churchlands’, strongly believe that through science one day we will replicate the human brain. To argue against this, I am putting forward the following true story.

I remember watching an Open University (London) education programme some years ago. A team of professors did an experiment on pavement hawkers in Bogota, Colombia. They were fruit sellers. The team bought a large number of miscellaneous items from these street vendors. This was repeated on a number of occasions. Within a few seconds, these vendors did mental calculations and came out with the amounts to be paid and the change was handed over equally fast. It was a success and repeatable and predictable. The team then took the sample population into a classroom situation and taught them basic arithmetic skills. After a few months of training they were given simple sums to do on selling fruit. Every one of them failed. These people had the brain structure that of ordinary human beings. They were skilled at their own jobs. But they could not be programmed to learn a set of rules. This poses the question whether we can create a perfect machine that will learn all the human transferable skills.

Computers and human brains excel at different tasks. For instance, a computer can remember things for an infinite amount of time. This is true as long as we don’t delete the computer files. Also, solving equations can be done in milliseconds. In my own experience when I was an undergraduate, I solved partial differential equations and it took me hours and a lot of paper. The present-day students have marvellous computer programmes for this. Let alone a mere student of mathematics, even a mathematical genius couldn’t rival computers in the above tasks. When it comes to languages, we can utter sentences of a completely foreign language after hearing it for the first time. Accents and slang can be decoded in our minds. Such algorithms, which we take for granted, will be very difficult for a computer.

I always maintain that there is more to intelligence than just being brilliant at quick thinking. A balanced human being to my mind is an intelligent person. An eccentric professor of Quantum Mechanics without feelings for life or people, cannot be considered an intelligent person. To people who may disagree with me, I shall give the benefit of the doubt and say most of the peoples’ intelligence is departmentalised. Intelligence is a total process.

Other limitations to AI

There are other limitations to artificial intelligence. The problems that existing computer programmes can handle are well-defined. There is a clear-cut way to decide whether a proposed solution is indeed the right one. In an algebraic equation, for example, the computer can check whether the variables and constants balance on both sides. But in contrast, many of the problems people face are ill-defined. As of yet, computer programmes do not define their own problems. It is not clear that computers will ever be able to do so in the way people do. Another crucial difference between humans and computers concerns “common sense”. An understanding of what is relevant and what is not. We possess it and computers don’t. The enormous amount of knowledge and experience about the world and its relevance to various problems computers are unlikely to have.

In this essay, I have attempted to discuss the merits and limitations of artificial intelligence, and by extension, computers. The evolution of the human brain has occurred over millennia, and creating a machine that truly matches human intelligence and is balanced in terms of emotions may be impossible or could take centuries

*The Chinese Room experiment, proposed by philosopher John Searle, challenges the idea that computers can truly “understand” language. Imagine a person locked in a room who does not know Chinese. They receive Chinese symbols through a slot and use an instruction manual to match them with other symbols to produce correct replies. To outsiders, it appears the person understands Chinese, but in reality, they are only following rules. Searle argues that similarly, a computer may process language convincingly without genuine understanding or consciousness.

by Sampath Anson Fernando

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoA question of national pride

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards