Features

The Times of Senthan: Little known Liberator and Silent Giant – I

From Political disillusionment towards armed struggle

by Rajan Hoole

Sharing with Senthan birth at the time when Gandhi was assassinated and Ceylon received independence, political controversies and liberation struggles of the era have chequered our lives. Reflecting on the 1971 JVP rebellion, Lionel Bopage has written, “… all alternative left groups strongly believed in the seizure of power through armed struggle for social transformation.”

Coevally, there were two other related upheavals whose roots were constitutional. Both the government and the Opposition clamoured for the absolute supremacy of Parliament. This was reflected in the debate in August 1968, where Dr. Colvin R. de Silva assailed the 1964 Privy Council ruling by Lord Pearce that Article 29 of the Soulbury Constitution, dealt with ‘further entrenched religious and racial matters, which shall not be the subject of legislation.’

The 1972 Constitution presided over by Colvin R. de Silva made parliamentary supremacy absolute and removed judicial checks on legislation, not only the Privy Council’s, but more importantly, Justice O. L. de Kretser’s voiding of Sinhala Only. To the Tamil minority, it was uprooting of the already much abused protections under Article 29 – which, in the words of Lord Pearce, represented the ‘solemn balance of rights,’ ‘the fundamental conditions on which [the citizens of Ceylon] inter se accepted the Constitution.’ The caution voiced by Sarath Muttetuwegama MP, went unheeded. Another upheaval was brewing.

From the time the supremacy of Parliament came into vogue after the English revolution of 1688, many wondered if the parliamentary cure for monarchical absolutism could be as dangerous as the disease. In 1701 Chief Justice Holt said intriguingly in City of London v. Wood, “[An Act of Parliament] may discharge one from his allegiance to the government he lives under.” He clarified, ‘if Parliament violated the limitations implied by natural law, it would be dissolved, and individuals living under it would be returned to the state of nature.’ One may wonder if a state of nature, as opposed to a state of law, is the one we now live under.

By the 1980s our children had become exposed to assassinations, aerial bombing, canon fire and sudden death as their early experiences. Palestine, Vietnam and Algeria we read about as boys had become part of our adult lives. Although Senthan and I were engineering students at the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya, from the late 1960s, I came to know him intimately much later. His sister Vasantha, with whom I used to have tea in the University of Jaffna Common Room, in the mid-1980s, told me that Senthan was coming home; then began our close friendship that lasted until Senthan died, on 14th June 2020. Despite common sympathies and regular conversations as good friends, it was in death that it struck me in a flow of memories and awakening of gratitude, that he had been, by far, both a rare genius and an eminent giant among dwarfs. The two cannot be separated.

Education, long and hard hours of work to earn our prestigious degrees, the laurels we lie upon and pronounce on every other subject in semi-ignorance, breeds in us harmful arrogance. What we do not acquire is humility, that there is an enormous treasure of the workings of the universe that we can never comprehend. Senthan’s father Pandit Veeragatthy, who influenced Senthan’s deep appreciation of the Tamil classics and his keen ability to separate the wheat from the chaff, is frequently remembered by my wife for his pithy saying, “Read selectively; what you must do, is to think!”

Pandit avoided increasingly dangerous political controversy. Once, a group of militant youth showed Pandit their map of Lanka, dominated by Tamil Eelam. Pandit responded in his acid irony, “Thambi, where are the others going to live?” Senthan was by contrast a committed person, but the former might explain his sardonic humour that helped him to survive in Jaffna’s hostile political environment. Those who knew the family well attribute the gentle side of Senthan to his mother, Nahamma, much admired in Vadamaratchy as a dedicated teacher.

Senthan paid little regard to people commending themselves by an array of impressive degrees, he was sceptical. Far from envy it was because his standard of intellectual excellence was highly exacting. It must show itself in the field of human relations, how a person regards questions of justice, how he treats others and applies his mind to these. He valued his mathematical training and what it taught him about analysing problems, social as well as engineering. While taking his degree studies at Peradeniya on the stride, he also spent a good deal of his time at the Jaffna Public Library reading the Times Literary Supplement among other writings. From Marxist authors he acquired a deep interest in liberation struggles around the world.

Life did not permit Senthan to carry a huge array of books from which he could quote chapter and verse. He followed the dictum ‘read, mark, learn and inwardly digest;’ and above all, think! He was a Marxist and a great admirer of Marx as a thinker. Che Guevara was for him a model of humanity and profound intellect, without diminishing the regard he had for the great Indian humanists Bharathy and Tagore, besides Gandhi. For him worthwhile achievement requires unremitting dedication combined with hard work and thorough research.

The Left in this country, he decried as the lazy Left that had let down the Plantation Tamils. He saw the Tamil intelligentsia as a lot who despite their educational attainments had intellectually gone to sleep. Otherwise, it was hard for him to understand how a large segment of the Tamil elite sporting impressive qualifications, prostrated themselves before the LTTE supremo because of their anger in the face of state instigated communal violence, without any foresight or concern over where it was carrying the Tamil people.

Dilemmas of Armed Struggle

The communal violence of 1958, where Tamils leading ordinary lives were punished with mayhem and murder by persons close to the centre of power, was notice given that any crime against them could be ignored at will. Discriminatory laws simply enacted would have been one matter; Senthan observed that what hurt the minorities most was the humiliation. After the communal violence of 1977, where there was strong evidence of the Police having instigated it with the complicity of the political authority, few among the younger Tamils said that an armed liberation struggle was out of order and many Sinhalese agreed, particularly the new generation of left inclined students in the universities and younger activists, some of whom had been involved in the 1971 JVP insurgency. The 1970s was the era of liberation struggles, of Vietnam, El Salvador and nearer home, the birth of Bangladesh.

Many of the young were deeply affected with a need for revolutionary transformation of the state in Lanka. Some names of students who were together in the Social Study Circle at Peradeniya University give us an idea: Gamini Samaranayake, Mahinda Deshapriya, Dayan Jayatilleke, K. Sritharan, Visvanandadevan, Raja Wijetunge, Karunatilake and Sunil Ratnapriya. Some who had been in the JVP rejected what they saw as its adventurism and political ideology that was superficial and eclectic. Links across communal barriers were also formed at the Marxist study circle of the veteran Marxist N. Shanmugathasan, one of whose erstwhile disciples was Rohana Wijeweera, the leader of the 1971 youth insurgency. It was at Shanmugathasan’s study circle that Rajani Rajasingham met Dayapala Thiranagama, whom she married.

Their aim was broadly a socialist Lanka with equality. Not all of them were ready for an armed struggle. But the pace among Tamils was forced by two events. One was the murder of Jaffna Mayor Alfred Duraiappa in July 1975 and the formation of the LTTE by a group around V. Prabhakaran, who had committed the murder. In 1976, this group met A. Amirthalingam, leader in waiting of the parliamentary Tamil nationalist TULF that made no pretence of condemning Duraiappa’s murder. The TULF had played a leading role in branding as traitors its parliamentary opponents, of whom Alfred Duraiappa was one.

This shadowy alliance with little substance between the TULF and the LTTE created the right amount of intimidation or approval that buttressed the TULF’s parliamentary monopoly in the North. The state instigated violence against Tamils soon after the 1977 elections changed the political situation drastically.

Even though the LTTE was relatively unknown and there was hope that the TULF would obtain justice for victims of the violence through the Sansoni commission of inquiry, arguments supporting a militant response grew in private conversation, especially among the Tamil expatriates, and drew increasing support. By the time of the PTA in 1979, there were movements that interested people could actually support. That these young men were placing their lives on the line for the public good provoked the question ‘what are you doing for the cause?’ It placed most people on the back foot. The existence of the cause was not disputed though few dared to take the next step that involved risk.

Even the young activists, many of them socialists, who opposed the LTTE’s intolerant nationalism and militarism, felt their credibility to be at stake unless they formed their own military wings. Visvanandadevan was a Marxist political activist who went against his temperament to form a military wing to his NLFT following July 1983. The result was the multiplication of groups, which additions the LTTE was quick to brand as criminal outfits. The militancy entered a new phase when the LTTE leader on 2 January 1982 used Seelan, a confidant of his, to murder Sundaram, a capable leader of the PLOTE that had split off from the LTTE. By this time the militancy had assumed a degree of legitimacy, where many others were ready to make excuses for such murders and preserve their complacency, ignoring the fatal effects of the malaise.

Once the people following the TULF’s cue had failed to condemn Duraiappah’s murder in 1975; through fear, confusion or complicity, Sundaram’s was dismissed as vendetta between armed groups and the disease festered. For those already associated with the LTTE condemnation would have been fatal.

For those of us who professed non-violence, our position seemed to have become merely ritual and even hypocritical; not least because in time taking on Sinhalese civilian targets had among many assumed a degree of legitimacy comparable to the destruction of German cities by Allied bombing during the Second World War. Even though Tamil civilians killed by the government forces’ atrocities formed the bulk of the dead, the massacres of unarmed Sinhalese civilians, particularly by the LTTE, failed to arouse the measure of moral indignation it deserved. Some social leaders applauded or bypassed these crimes as a legitimate means of defence. The best among us had to constantly check ourselves not to fall prey to the inhuman within.

Amidst this moral anarchy of civilian killings on both sides, the view of militant groups, in spite of their crimes, as defenders of the Tamil people and ‘our boys’, gained strength. For Rajani, whose heart was moved by the sacrificial ardour of some militants, particularly Seelan, whose accidental injury in 1982 no other doctor in Jaffna would treat, guided her first steps into the LTTE. However, Seelan’s fate within the LTTE, his self-isolation and death in an army ambush, was one of the eye openers which convinced Rajani of its utter inhumanity, a conviction for which she paid with her life. Her husband Dayapala who made his observations from his vantage in the Rajasingham household had warned her, having read the signs when Sundaram was killed.

After her disillusionment, Rajani’s motherly ardour was extended to the young whom she saw were by circumstances absorbed into the LTTE; which in turn threw them on the scrap heap as human wrecks after having squeezed out their dedication and humanity like sucked lemon. It took me until April 1986 when the LTTE wiped out its fellow militant group TELO to completely rule them out as capable of any good. Senthan’s grasp of political reality matched by his humanity was far in advance of the rest of his generation. There was no confusion in his grasp of what was criminal. (Part II will be published tomorrow.)

Features

Trump’s Interregnum

Trump is full of surprises; he is both leader and entertainer. Nearly nine hours into a long flight, a journey that had to U-turn over technical issues and embark on a new flight, Trump came straight to the Davos stage and spoke for nearly two hours without a sip of water. What he spoke about in Davos is another issue, but the way he stands and talks is unique in this 79-year-old man who is defining the world for the worse. Now Trump comes up with the Board of Peace, a ticket to membership that demands a one-billion-dollar entrance fee for permanent participation. It works, for how long nobody knows, but as long as Trump is there it might. Look at how many Muslim-majority and wealthy countries accepted: Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, Jordan, Qatar, Pakistan, Indonesia, and the United Arab Emirates are ready to be on board. Around 25–30 countries reportedly have already expressed the willingness to join.

The most interesting question, and one rarely asked by those who speak about Donald J. Trump, is how much he has earned during the first year of his second term. Liberal Democrats, authoritarian socialists, non-aligned misled-path walkers hail and hate him, but few look at the financial outcome of his politics. His wealth has increased by about three billion dollars, largely due to the crypto economy, which is why he pardoned the founder of Binance, the China-born Changpeng Zhao. “To be rich like hell,” is what Trump wanted. To fault line liberal democracy, Trump is the perfect example. What Trump is doing — dismantling the old façade of liberal democracy at the very moment it can no longer survive — is, in a way, a greater contribution to the West. But I still respect the West, because the West still has a handful of genuine scholars who do not dare to look in the mirror and accept the havoc their leaders created in the name of humanity.

Democracy in the Arab world was dismantled by the West. You may be surprised, but that is the fact. Elizabeth Thompson of American University, in her book How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs, meticulously details how democracy was stolen from the Arabs. “No ruler, no matter how exalted, stood above the will of the nation,” she quotes Arab constitutional writing, adding that “the people are the source of all authority.” These are not the words of European revolutionaries, nor of post-war liberal philosophers; they were spoken, written and enacted in Syria in 1919–1920 by Arab parliamentarians, Islamic reformers and constitutionalists who believed democracy to be a universal right, not a Western possession. Members of the Syrian Arab Congress in Damascus, the elected assembly that drafted a democratic constitution declaring popular sovereignty — were dissolved by French colonial forces. That was the past; now, with the Board of Peace, the old remnants return in a new form.

Trump got one thing very clear among many others: Western liberal ideology is nothing but sophisticated doublespeak dressed in various forms. They go to West Asia, which they named the Middle East, and bomb Arabs; then they go to Myanmar and other places to protect Muslims from Buddhists. They go to Africa to “contribute” to livelihoods, while generations of people were ripped from their homeland, taken as slaves and sold.

How can Gramsci, whose 135th birth anniversary fell this week on 22 January, help us escape the present social-political quagmire? Gramsci was writing in prison under Mussolini’s fascist regime. He produced a body of work that is neither a manifesto nor a programme, but a theory of power that understands domination not only as coercion but as culture, civil society and the way people perceive their world. In the Prison Notebooks he wrote, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old world is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid phenomena appear.” This is not a metaphor. Gramsci was identifying the structural limbo that occurs when foundational certainties collapse but no viable alternative has yet emerged.

The relevance of this insight today cannot be overstated. We are living through overlapping crises: environmental collapse, fragmentation of political consensus, erosion of trust in institutions, the acceleration of automation and algorithmic governance that replaces judgment with calculation, and the rise of leaders who treat geopolitics as purely transactional. Slavoj Žižek, in his column last year, reminded us that the crisis is not temporary. The assumption that history’s forward momentum will automatically yield a better future is a dangerous delusion. Instead, the present is a battlefield where what we thought would be the new may itself contain the seeds of degeneration. Trump’s Board of Peace, with its one-billion-dollar gatekeeping model, embodies this condition: it claims to address global violence yet operates on transactional logic, prioritizing wealth over justice and promising reconstruction without clear mechanisms of accountability or inclusion beyond those with money.

Gramsci’s critique helps us see this for what it is: not a corrective to global disorder, but a reenactment of elite domination under a new mechanism. Gramsci did not believe domination could be maintained by force alone; he argued that in advanced societies power rests on gaining “the consent and the active participation of the great masses,” and that domination is sustained by “the intellectual and moral leadership” that turns the ruling class’s values into common sense. It is not coercion alone that sustains capitalism, but ideological consensus embedded in everyday institutions — family, education, media — that make the existing order appear normal and inevitable. Trump’s Board of Peace plays directly into this mode: styled as a peace-building institution, it gains legitimacy through performance and symbolic endorsement by diverse member states, while the deeper structures of inequality and global power imbalance remain untouched.

Worse, the Board’s structure, with contributions determining permanence, mimics the logic of a marketplace for geopolitical influence. It turns peace into a commodity, something to be purchased rather than fought for through sustained collective action addressing the root causes of conflict. But this is exactly what today’s democracies are doing behind the scenes while preaching rules-based order on the stage. In Gramsci’s terms, this is transformismo — the absorption of dissent into frameworks that neutralize radical content and preserve the status quo under new branding.

If we are to extract a path out of this impasse, we must recognize that the current quagmire is more than political theatre or the result of a flawed leader. It arises from a deeper collapse of hegemonic frameworks that once allowed societies to function with coherence. The old liberal order, with its faith in institutions and incremental reform, has lost its capacity to command loyalty. The new order struggling to be born has not yet articulated a compelling vision that unifies disparate struggles — ecological, economic, racial, cultural — into a coherent project of emancipation rather than fragmentation.

To confront Trump’s phenomenon as a portal — as Žižek suggests, a threshold through which history may either proceed to annihilation or re-emerge in a radically different form — is to grasp Gramsci’s insistence that politics is a struggle for meaning and direction, not merely for offices or policies. A Gramscian approach would not waste energy on denunciation alone; it would engage in building counter-hegemony — alternative institutions, discourses, and practices that lay the groundwork for new popular consent. It would link ecological justice to economic democracy, it would affirm the agency of ordinary people rather than treating them as passive subjects, and it would reject the commodification of peace.

Gramsci’s maxim “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” captures this attitude precisely: clear-eyed recognition of how deep and persistent the crisis is, coupled with an unflinching commitment to action. In an age where AI and algorithmic governance threaten to redefine humanity’s relation to decision-making, where legitimacy is increasingly measured by currency flows rather than human welfare, Gramsci offers not a simple answer but a framework to understand why the old certainties have crumbled and how the new might still be forged through collective effort. The problem is not the lack of theory or insight; it is the absence of a political subject capable of turning analysis into a sustained force for transformation. Without a new form of organized will, the interregnum will continue, and the world will remain trapped between the decay of the old and the absence of the new.

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa ✍️

Features

India, middle powers and the emerging global order

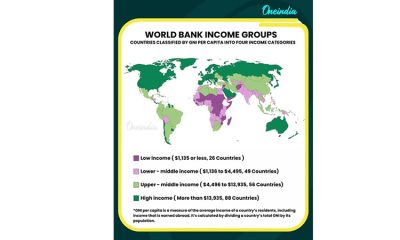

Designed by the victors and led by the US, its institutions — from the United Nations system to Bretton Woods — were shaped to preserve western strategic and economic primacy. Yet despite their self-serving elements, these arrangements helped maintain a degree of global stability, predictability and prosperity for nearly eight decades. That order is now under strain.

This was evident even at Davos, where US President Donald Trump — despite deep differences with most western allies — framed western power and prosperity as the product of a shared and “very special” culture, which he argued must be defended and strengthened. The emphasis on cultural inheritance, rather than shared rules or institutions, underscored how far the language of the old order has shifted.

As China’s rise accelerates and Russia grows more assertive, the US appears increasingly sceptical of the very system it once championed. Convinced that multilateral institutions constrain American freedom of action, and that allies have grown complacent under the security umbrella, Washington has begun to prioritise disruption over adaptation — seeking to reassert supremacy before its relative advantage diminishes further.

What remains unclear is what vision, if any, the US has for a successor order. Beyond a narrowly transactional pursuit of advantage, there is little articulation of a coherent alternative framework capable of delivering stability in a multipolar world.

The emerging great powers have not yet filled this void. India and China, despite their growing global weight and civilisational depth, have largely responded tactically to the erosion of the old order rather than advancing a compelling new one. Much of their diplomacy has focused on navigating uncertainty, rather than shaping the terms of a future settlement. Traditional middle powers — Japan, Germany, Australia, Canada and others — have also tended to react rather than lead. Even legacy great powers such as the United Kingdom and France, though still relevant, appear constrained by alliance dependencies and domestic pressures.

st Asia, countries such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE have begun to pursue more autonomous foreign policies, redefining their regional and global roles. The broader pattern is unmistakable. The international system is drifting toward fragmentation and narrow transactionalism, with diminishing regard for shared norms or institutional restraint.

Recent precedents in global diplomacy suggest a future in which arrangements are episodic and power-driven. Long before Thucydides articulated this logic in western political thought, the Mahabharata warned that in an era of rupture, “the strong devour the weak like fish in water” unless a higher order is maintained. Absent such an order, the result is a world closer to Mad Max than to any sustainable model of global governance.

It is precisely this danger that Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney alluded to in his speech at Davos on Wednesday. Warning that “if great powers abandon even the pretense of rules and values for the unhindered pursuit of their power and interests, the gains from transactionalism will become harder to replicate,” Carney articulated a concern shared by many middle powers. His remarks underscored a simple truth: Unrestrained power politics ultimately undermine even those who believe they benefit from them.

Carney’s intervention also highlights a larger opportunity. The next phase of the global order is unlikely to be shaped by a single hegemon. Instead, it will require a coalition — particularly of middle powers — that have a shared interest in stability, openness and predictability, and the credibility to engage across ideological and geopolitical divides. For many middle powers, the question now is not whether the old order is fraying, but who has the credibility and reach to help shape what comes next.

This is where India’s role becomes pivotal. India today is no longer merely a balancing power. It is increasingly recognised as a great power in its own right, with strong relations across Europe, the Indo-Pacific, West Asia, Africa and Latin America, and a demonstrated ability to mobilise the Global South. While India’s relationship with Canada has experienced periodic strains, there is now space for recalibration within a broader convergence among middle powers concerned about the direction of the international system.

One available platform is India’s current chairmanship of BRICS — if approached with care. While often viewed through the prism of great-power rivalry, BRICS also brings together diverse emerging and middle powers with a shared interest in reforming, rather than dismantling, global governance. Used judiciously, it could complement existing institutions by helping articulate principles for a more inclusive and functional order.

More broadly, India is uniquely placed to convene an initial core group of like-minded States — middle powers, and possibly some open-minded great powers — to begin a serious conversation about what a new global order should look like. This would not be an exercise in bloc-building or institutional replacement, but an effort to restore legitimacy, balance and purpose to international cooperation. Such an endeavour will require political confidence and the willingness to step into uncharted territory. History suggests that moments of transition reward those prepared to invest early in ideas and institutions, rather than merely adapt to outcomes shaped by others.

The challenge today is not to replicate Bretton Woods or San Francisco, but to reimagine their spirit for a multipolar age — one in which power is diffused, interdependence unavoidable, and legitimacy indispensable. In a world drifting toward fragmentation, India has the credibility, relationships and confidence to help anchor that effort — if it chooses to lead.

(The Hindustan Times)

(Milinda Moragoda is a former Cabinet Minister and diplomat from Sri Lanka and founder of the Pathfinder Foundation, a strategic affairs think tank. this article can read on

https://shorturl.at/HV2Kr and please contact via email@milinda.org)

by Milinda Moragoda ✍️

For many middle powers, the question now is not whether the old order is fraying,

but who has the credibility and reach to help shape what comes next

Features

The Wilwatte (Mirigama) train crash of 1964 as I recall

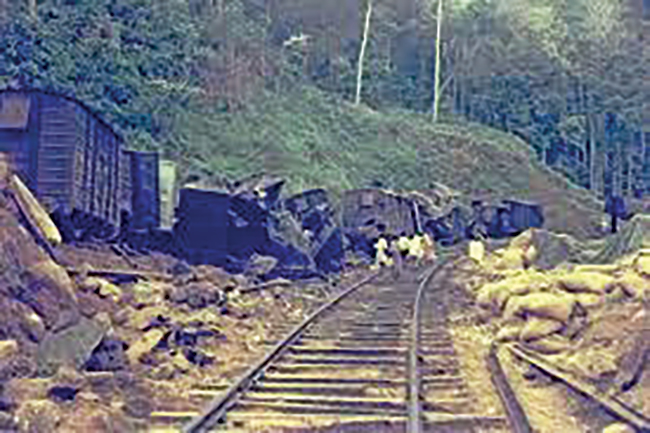

Back in 1964, I was working as DMO at Mirigama Government Hospital when a major derailment of the Talaimannar/Colombo train occurred at the railway crossing in Wilwatte, near the DMO’s quarters. The first major derailment, according to records, took place in Katukurunda on March 12, 1928, when there was a head-on collision between two fast-moving trains near Katukurunda, resulting in the deaths of 28 people.

Please permit me to provide details concerning the regrettable single train derailment involving the Talaimannar Colombo train, which occurred in October 1964 at the Wilwatte railway crossing in Mirigama.

This is the first time I’m openly sharing what happened on that heartbreaking morning, as I share the story of the doctor who cared for all the victims. The Health Minister, the Health Department, and our community truly valued my efforts.

By that time, I had qualified with the Primary FRCS and gained valuable surgical experience as a registrar at the General Hospital in Colombo. I was hopeful to move to the UK to pursue the final FRCS degree and further training. Sadly, all scholarships were halted by Hon. Felix Dias Bandaranaike, the finance minister in the Bandaranaike government in 1961.

Consequently, I was transferred to Mirigama as the District Medical Officer in 1964. While training as an emerging surgeon without completing the final fellowship in the United Kingdom, I established an operating theatre in one of the hospital’s large rooms. A colleague at the Central Medical Stores in Maradana assisted me in acquiring all necessary equipment for the operating theatre, unofficially. Subsequently, I commenced performing minor surgeries under spinal anaesthesia and local anaesthesia. Fortunately, I was privileged to have a theatre-trained nursing sister and an attendant trainee at the General Hospital in Colombo.

Therefore, I was prepared to respond to any accidental injuries. I possessed a substantial stock of plaster of Paris rolls for treating fractures, and all suture material for cuts.

I was thoroughly prepared for any surgical mishaps, enabling me to manage even the most significant accidental incidents.

On Saturday, October 17, 1964, the day of the train derailment at the railway crossing at Wilwatte, Mirigama, along the Main railway line near Mirigama, my house officer, Janzse, called me at my quarters and said, “Sir, please come promptly; numerous casualties have been admitted to the hospital following the derailment.”

I asked him whether it was an April Fool’s stunt. He said, ” No, Sir, quite seriously.

I promptly proceeded to the hospital and directly accessed the operating theatre, preparing to attend to the casualties.

Meanwhile, I received a call from the site informing me that a girl was trapped on a railway wagon wheel and may require amputation of her limb to mobilise her at the location along the railway line where she was entrapped.

My theatre staff transported the surgical equipment to the site. The girl was still breathing and was in shock. A saline infusion was administered, and under local anaesthesia, I successfully performed the limb amputation and transported her to the hospital with my staff.

On inquiring, she was an apothecary student going to Colombo for the final examination to qualify as an apothecary.

Although records indicate that over forty passengers perished immediately, I recollect that the number was 26.

Over a hundred casualties, and potentially a greater number, necessitate suturing of deep lacerations, stabilisation of fractures, application of plaster, and other associated medical interventions.

No patient was transferred to Colombo for treatment. All casualties received care at this base hospital.

All the daily newspapers and other mass media commended the staff team for their commendable work and the attentive care provided to all casualties, satisfying their needs.

The following morning, the Honourable Minister of Health, Mr M. D. H. Jayawardena, and the Director of Health Services, accompanied by his staff, arrived at the hospital.

I did the rounds with the official team, bed by bed, explaining their injuries to the minister and director.

Casualties expressed their commendation to the hospital staff for the care they received.

The Honourable Minister engaged me privately at the conclusion of the rounds. He stated, “Doctor, you have been instrumental in our success, and the public is exceedingly appreciative, with no criticism. As a token of gratitude, may I inquire how I may assist you in return?”

I got the chance to tell him that I am waiting for a scholarship to proceed to the UK for my Fellowship and further training.

Within one month, the government granted me a scholarship to undertake my fellowship in the United Kingdom, and I subsequently travelled to the UK in 1965.

On the third day following the incident, Mr Don Rampala, the General Manager of Railways, accompanied by his deputy, Mr Raja Gopal, visited the hospital. A conference was held at which Mr Gopal explained and demonstrated the circumstances of the derailment using empty matchboxes.

He explained that an empty wagon was situated amid the passenger compartments. At the curve along the railway line at Wilwatte, the engine driver applied the brakes to decelerate, as Mirigama Railway Station was only a quarter of a mile distant.

The vacant wagon was lifted and transported through the air. All passenger compartments behind the wagon derailed, whereas the engine and the frontcompartments proceeded towards the station without the engine driver noticing the mishap.

After this major accident, I was privileged to be invited by the General Manager of the railways for official functions until I left Mirigama.

The press revealed my identity as the “Wilwatte Hero”.

This document presents my account of the Wilwatte historic train derailment, as I distinctly recall it.

Recalled by Dr Harold Gunatillake to serve the global Sri Lankan community with dedication. ✍️

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoHistory of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine Kandana

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe middle-class money trap: Why looking rich keeps Sri Lankans poor

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days ago‘Building Blocks’ of early childhood education: Some reflections