Features

The problems of life

(from Venerable Nārada Mahāther’s THE BUDDHA AND HIS TEACHINGS)

Who? Whence? Whither? Why? What? are some important problems that affect all humanity.

1) Who is man? is our first question.

Let us proceed with what is self-evident and perceptible to all.

Man possesses a body which is seen either by our senses or by means of apparatus. This material body consists of forces and qualities which are in a state of constant flux.

Scientists find it difficult to define what matter is. Certain philosophers define “matter as that in which proceed the changes called motion, and motion as those changes which proceed in matter.”

The Pāli term for matter is Rūpa. It is explained as that which changes or disintegrates. That which manifests itself is also another explanation.

According to Buddhism there are four fundamental material elements. They are Pathavi, Āpo, Tejo, and Vāyo

Pathavi means the element of extension, the substratum of matter. Without it, objects cannot occupy space. The qualities of hardness and softness which are purely relative are two conditions of this element. This element of extension is present in earth, water, fire and air. For instance, the water above is supported by water below. It is this element of extension in conjunction with the element of motion (Vāyo) that produces the upward pressure. Heat or cold is the Tejo element, while fluidity is the Āpo element.

Āpo

is the element of cohesion. Unlike Pathavi it is intangible. It is this element which enables the scattered atoms of matter to cohere and thus gives us the idea of body.

Tejo

is the element of heat. Cold is also a form of Tejo. Both heat and cold are included in Tejo because they possess the power of maturing bodies, or, in other words, the vitalising energy. Preservation and decay are due to this element.

Vāyo

is the element of motion. The movements are caused by this element. Motion is regarded as the force or the generator of heat. Both motion and heat in the material realm correspond respectively to consciousness and Kamma in the mental.

These four powerful forces are inseparable and interrelated, but one element may preponderate over another, as, for instance, the element of extension preponderates in earth; cohesion, in water; heat, in fire; and motion, in air.

Thus, matter consists of forces and qualities which constantly change, not remaining the same even for two consecutive moments. According to Buddhism, matter endures only for 17 thought-moments. [2]

At the moment of birth, according to biology, man inherits from his parents an infinitesimally minute cell 30 millionth part of an inch across. “In the course of nine months this speck grows to a living bulk 15,000 million times greater than it was at outset. [3] This tiny chemico-physical cell is the physical foundation of man.

According to Buddhism sex is also determined at the moment of conception.

Combined with matter there is another important factor in this complex machinery of man. It is the mind. As such it pleases some learned writers to say that man is not Mind plus Body, but is a Mind-Body. Scientists declare that life emerges from matter and mind from life. But they do not give us a satisfactory explanation with regard to the development of the mind

Unlike the material body immaterial mind is invisible, but it could be sensed directly. An old couplet runs:-

“What is mind? No matter.What is matter? Never mind.”

We are aware of our thoughts and feelings and so forth by direct sensation, and we infer their existence in others by analogy.

There are several Pāli terms for mind. Mana, Citta, Vijgana the most noteworthy of them. Compare the Pāli root man, to think, with the English word man and the Pāli word Manussa which means he who has a developed consciousness.

In Buddhism no distinction is made between mind and consciousness. Both are used as synonymous terms. Mind may be defined as simply the awareness of an object since there is no agent or a soul that directs all activities. It consists of fleeting mental states which constantly arise and perish with lightning rapidity. “With birth for its source and death for its mouth it persistently flows on like a river receiving from the tributary streams of sense constant accretions to its flood.” Each momentary consciousness of this ever-changing life-stream, on passing away, transmits its whole energy, all the indelibly recorded impressions, to its successor. Every fresh consciousness therefore consists of the potentialities of its predecessors and something more. As all impressions are indelibly recorded in this ever-changing palimpsest-like mind, and as all potentialities are transmitted from life to life, irrespective of temporary physical disintegrations, reminiscence of past births or past incidents becomes a possibility. If memory depends solely on brain cells, it becomes an impossibility.

Like electricity mind is both a constructive and destructive powerful force. It is like a double-edged weapon that can equally be used either for good or evil. One single thought that arises in this invisible mind can even save or destroy the world. One such thought can either populate or depopulate a whole country. It is mind that creates one’s heaven. It is mind that creates one’s hell.

Ouspensky writes: “Concerning the latent energy contained in the phenomena of consciousness, i.e. in thoughts, feelings, desires, we discover that its potentiality is even more immeasurable, more boundless. From personal experience, from observation, from history, we know that ideas, feelings, desires, manifesting themselves, can liberate enormous quantities of energy, and create infinite series of phenomena. An idea can act for centuries and millennia and only grow and deepen, evoking ever new series of phenomena, liberating ever fresh energy. We know that thoughts continue to live and act when even the very name of the man who created them has been converted into a myth, like the names of the founders of ancient religions, the creators of the immortal poetical works of antiquity, heroes, leaders, and prophets. Their words are repeated by innumerable lips, their ideas are studied and commented upon.

“Undoubtedly each thought of a poet contains enormous potential force, like the power confined in a piece of coal or in a living cell, but infinitely more subtle, imponderable and potent. [4]”

Observe, for instance, the potential force that lies in the following significant words of the Buddha:

— Mano-pubbangāma dhammā ? mano – setthā – manomayā.Mind fore-runs deeds; mind is chief, and mind-made are they.

Mind or consciousness, according to Buddhism, arises at the very moment of conception, together with matter. Consciousness is therefore present in the foetus. This initial consciousness, technically known as rebirth-consciousness or relinking-consciousness (Patisandhi vijnna), is conditioned by past kamma of the person concerned. The subtle mental, intellectual, and moral differences that exist amongst mankind are due to this Kamma conditioned consciousness, the second factor of man.

To complete the trio that constitutes man there is a third factor, the phenomenon of life that vitalises both mind and matter. Due to the presence of life reproduction becomes possible. Life manifests itself both in physical and mental phenomena. In Pāli the two forms of life are termed Nāma jivitindriya and Rūpa jivitindriya — psychic and physical life.

Matter, mind, and life are therefore the three distinct factors that constitute man. With their combination a powerful force known as man with inconceivable possibilities comes into being. He becomes his own creator and destroyer. In him are found a rubbish-heap of evil and a storehouse of virtue. In him are found the worm, the brute, the man, the superman, the deva, the Brahma. Both criminal tendencies and saintly characteristics are dormant in him. He may either be a blessing or a curse to himself and others. In fact, man is a world by himself.

2) Whence? is our second question. How did man originate’?

Either there must be a beginning for man or there cannot be a beginning. Those who belong to the first school postulate a first cause, whether as a cosmic force or as an Almighty Being. Those who belong to the second school deny a first cause for, in common experience, the cause ever becomes the effect and the effect becomes the cause. In a circle of cause and effect a first cause is inconceivable. According to the former life has had a beginning; while according to the latter it is beginningless. In the opinion of some the conception of a first cause is as ridiculous as a round triangle.

According to the scientific standpoint, man is the direct product of the sperm and ovum cells provided by his parents. Scientists while asserting “Omne vivum ex vivo”--all life from life, maintain, that mind and life evolved from the lifeless.

Now, from the scientific standpoint, man is absolutely parent-born. As such life precedes life. With regard to the origin of the first protoplasm of life, or “colloid” (whichever we please to call it), scientists plead ignorance.

According to Buddhism, man is born from the matrix of action (kammayoni). Parents merely provide man with a material layer. As such being precedes being. At the moment of conception, it is Kamma that conditions the initial consciousness that vitalizes the foetus. It is this invisible Kammic energy generated from the past birth that produces mental phenomena and the phenomenon of life in an already extant physical phenomenon, to complete the trio that constitutes man.

Dealing with the conception of beings the Buddha states:

“Where three are found in combination, there a germ of life is planted. If mother and father come together, but it is not the mother’s period, and the ‘being-to-be born’ (gandhabba) is not present, then no germ of life is planted. If mother and father come together, and it is the mother’s period, but the ‘being-to-be-born’ is not present, then again, no germ of life is planted. If mother and father come together, and it is the mother’s period, and the ‘being-to-bc-born’ is also present, then, by the combination of these three, a germ of life is there planted.”

Here Gandhabba (= gantabba) refers to a suitable being ready to be born in that particular womb. This term is used only in this particular connection, and must not be mistaken for a permanent soul.

For a being to be born here a being must die somewhere. The birth of a being corresponds to the death of a being in a past life; just as, in conventional terms, the rising of the sun in one place means the setting of the sun in another place.

The Buddha states: “a first beginning of beings who, obstructed by ignorance and fettered by craving, wander and fare on, is not to be perceived.”

This life-stream flows ad infinitum as long as it is fed with the muddy waters of ignorance and craving. When these two are completely cut off, then only does the life-stream cease to flow; rebirth ends as in the case of Buddhas and Arahants. An ultimate beginning of this life-stream cannot be determined, as a stage cannot be perceived when this life force was not fraught with ignorance and craving.

The Buddha has here referred merely to the beginning of the life-stream of living beings. It is left to scientists to speculate on the origin and the evolution of the universe.

3) Whither? is our third question.

Where goes man?

According to ancient materialism which, in Pāli and Samskrit, is known as Lokāyata, man is annihilated after death, leaving behind him any force generated by him. “Man is composed of four elements. When man dies the earthy element returns and relapses into the earth; the watery element returns into the water; the fiery element returns into the fire; the airy element returns into the air, the senses pass into space.

Wise and fools alike, when the body dissolves. are cut off, perish, do not exist any longer. There is no other world. Death is the end of all. This present world alone is real.

The so-called eternal heaven and hell are the inventions of imposters.

Materialists believe only in what is cognizable by the senses. As such matter alone is real. The ultimate principles are the four elements — earth, water, fire and air. The self-conscious life mysteriously springs forth from them, just as the genie makes its appearance when Aladdin rubs his lamp. The brain secretes thought just as liver secretes bile.

In the view of materialists the belief in the other world, as Sri Radhakrishna states, “is a sign of mendaciousness, feminism, weakness, cowardice and dishonesty.”

According to Christianity there is no past for man. The present is only a preparation for two eternities of heaven and hell. Whether they are viewed as places or states man has for his future endless felicity in heaven or endless suffering in hell. Man is therefore not annihilated after death, but his essence goes to eternity.

“Whoever,” as Schopenhaeur says, “regards himself as having become out of nothing must also think that he will again become nothing; or that an eternity has passed before he was, and then a second eternity had begun, through which he will never cease to be, is a monstrous thought.”

The adherents of Hinduism who believe in a past and present do not state that man is annihilated after death. Nor do they say that man is eternalized after death. They believe in an endless series of past and future births. In their opinion the life-stream of man flows ad infinitum as long as it is propelled by the force of Kamma, one’s actions. In due course the essence of man may be reabsorbed into Ultimate Reality (Paramātma) from which his soul emanated.

Buddhism believes in the present. With the present as the basis it argues the past and future. Just as an electric light is the outward manifestation of invisible electric energy even so man is merely the outward manifestation of an invisible energy known as Kamma. The bulb may break, and the light may be extinguished, but the current remains and the light may be reproduced in another bulb. In the same way the Kammic force remains undisturbed by the disintegration of the physical body, and the passing away of the present consciousness leads to the arising of a fresh one in another birth. Here the electric current is like the Kammic force, and the bulb may be compared to the egg-cell provided by the parents.

Past Kamma conditions the present birth; and present Kamma, in combination with past Kamma, conditions the future. The present is the offspring of the past, and becomes in turn the parent of the future.

Death is therefore not the complete annihilation of man, for though that particular life span ended, the force which hitherto actuated it is not destroyed.

After death the life-flux of man continues ad infinitum as long as it is fed with the waters of ignorance and craving. In conventional terms man need not necessarily be born as a man because humans are not the only living beings. Moreover, earth, an almost insignificant speck in the universe, is not the only place in which he will seek rebirth. He may be born in other habitable planes as well. [6]

If man wishes to put and end to this repeated series of births, he can do so as the Buddha and Arahants have done by realizing Nibbāna, the complete cessation of all forms of craving.

Where does man go? He can go wherever he wills or likes if he is fit for it. If, with no particular wish, he leaves his path to be prepared by the course of events, he will go to the place or state he fully deserves in accordance with his Kamma.

4) Why? is our last question.

Why is man? Is there a purpose in life? This is rather a controversial question.

What is the materialistic standpoint? Scientists answer:

“Has life purpose? What, or where, or when?Out of space came Universe, came Sun,Came Earth, came Life, came Man, and more must come.But as to Purpose: whose or whence? Why, None.”

As materialists confine themselves purely to sense-data and the present material welfare ignoring all spiritual values, they hold a view diametrically opposite to that of moralists. In their opinion there is no purposer — hence there cannot be a purpose. Non-theists, to which category belong Buddhists as well, do not believe in a creative purposer.

“Who colours wonderfully the peacocks, or who makes the cuckoos coo so well?” This is one of the chief arguments of the materialists to attribute everything to the natural order of things.

“Eat, drink, and be merry, for death comes to all, closing our lives,” appears to be the ethical ideal of their system. In their opinion, as Sri Radhakrishna writes: “Virtue is a delusion and enjoyment is the only reality. Death is the end of life. Religion is a foolish aberration, a mental disease. There was a distrust of everything good, high, pure, and compassionate. The theory stands for sensualism and selfishness and the gross affirmation of the loud will. There is no need to control passion and instinct, since they are nature’s legacy to men. “

Sarvadarsana Sangraha says:

“While life is yours, live joyously,None can escape Death’s searching eye;When once this frame of ours they burn,How shall it e’er again return? [8]”

“While life remains let a man live happily, let him feed on ghee even though he runs in debt.”

Now let us turn towards science to get a solution to the question “why.”

It should be noted that “science is a study of things, a study of what is and that religion is a study of ideals, a study of what should be.”

Sir J. Arthur Thompson maintains that science is incomplete because it cannot answer the question why.

Dealing with cosmic Purpose, Bertrand Russell states three kinds of views — theistic, pantheistic, and emergent. “The first”, he writes, “holds that God created the world and decreed the laws of nature because he foresaw that in time some good would be evolved. In this view purpose exists consciously in the mind of the Creator, who remains external to His creation.

“In the ‘pantheistic’ form, God is not external to the universe, but is merely the universe considered as a whole. There cannot therefore be an act of creation, but there is a kind of creative force in the universe, which causes it to develop according to a plan which this creative force may be said to have had in mind throughout the process.

“In the ’emergent’ form the purpose is more blind. At an earlier stage, nothing in the universe foresees a later stage, but a kind of blind impulsion leads to those changes which bring more developed forms into existence, so that, in some rather obscure sense, the end is implicit in the beginning. [9]”

We offer no comments. These are merely the views of different religionists and great thinkers.

Whether there is a cosmic purpose or not a question arises as to the usefulness of the tapeworm, snakes, mosquitoes and so forth, and for the existence of rabies. How does one account for the problem of evil? Are earthquakes, floods, pestilences, and wars designed?

Expressing his own view about Cosmic Purpose, Russell boldly declares: “Why in any case, this glorification of man? How about lions and tigers? They destroy fewer animals or human lives than we do, and they are much more beautiful than we are. How about ants? They manage the Corporate State much better than any Fascist. Would not a world of nightingales and larks and deer be better than our human world of cruelty and injustice and war?

The believers in cosmic purpose make much of our supposed intelligence, but their writings make one doubt it. If I were granted omnipotence, and millions of years to experiment in, I should not think Man much to boast of as the final result of all my efforts. “

What is the purpose of life according to different religions?

According to Hinduism the purpose of life is “to be one with Brahma” or “to be re-absorbed in the Divine Essence from which his soul emanated.”

According to Judaism, Christianity and Islam, it is “to glorify God and to enjoy Him forever.”

Will an average person of any religion be prepared to give up his earthly life, to which he tenaciously clings, for immortality in their ultimate havens of peace?

Very doubtful, indeed!

* * *

Now, how does Buddhism answer the question “why?”

Buddhism denies the existence of a Creator. As such from a Buddhist standpoint there cannot be a fore-ordained purpose. Nor does Buddhism advocate fatalism, determinism, or pre-destination which controls man’s future independent of his free actions. In such a case freewill becomes an absolute farce and life becomes purely mechanistic.

To a large extent man’s actions are more or less mechanistic, being influenced by his own doings, upbringing, environment and so forth. But to a certain extent man can exercise his freewill. A person, for instance, falling from a cliff will be attracted to the ground just as an inanimate stone would. In this case he cannot use his freewill although he has a mind unlike the stone. If he were to climb a cliff, he could certainly use his freewill and act as he likes. A stone, on the contrary, is not free to do so of its own accord. Man has the power to choose between right and wrong, good and bad. Man can either be hostile or friendly to himself and others. It all depends on his mind and its development.

Although there is no specific purpose in man’s existence, yet man is free to have some purpose in life.

What, therefore, is the purpose of life?

Ouspensky writes “Some say that the meaning of life is in service, in the surrender of self, in self-sacrifice, in the sacrifice of everything, even life itself. Others declare that the meaning of life is in the delight of it, relieved against ‘the expectation of the final horror of death.’ Some say that the meaning of life is in perfection, and the creation of a better future beyond the grave, or in future life for ourselves. Others say that the meaning of life is in the approach to non-existence; still others, that the meaning of life is in the perfection of the race, in the organization of life on earth; while there are those who deny the possibility of even attempting to know its meaning.”

Criticising all these views the learned writer says:–“The fault of all these explanations consists in the fact that they all attempt to discover the meaning of life outside of itself, either in the nature of humanity, or in some problematical existence beyond the grave, or again in the evolution of the Ego throughout many successive incarnations — always in something outside of the present life of man. But if instead of thus speculating about it, men would simply look within themselves, then they would see that in reality the meaning of life is not after all so obscure. It consists in knowledge. “

In the opinion of a Buddhist, the purpose of life is Supreme Enlightenment (Sambodhi), i.e. understanding of oneself as one really is. This may be achieved through sublime conduct, mental culture, and penetrative insight; or in other words, through service and perfection.

In service are included boundless loving-kindness, compassion, and absolute selflessness which prompt man to be of service to others. Perfection embraces absolute purity and absolute wisdom.

Features

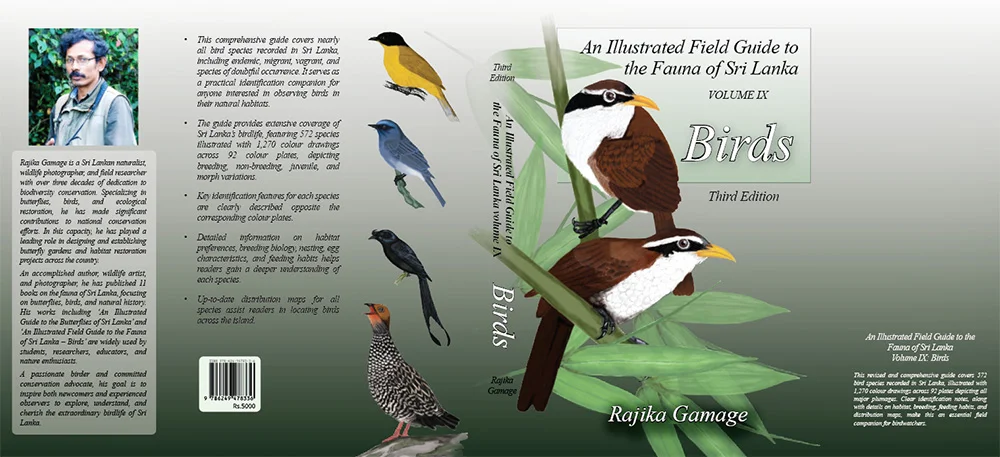

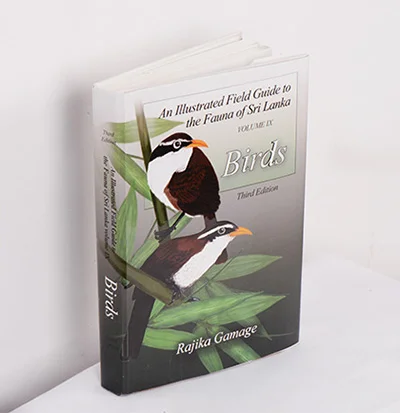

A life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

Sri Lanka wakes each morning to wings.

From the liquid whistle of a magpie robin in a garden hedge to the distant circling silhouette of an eagle above a forest canopy, birds define the rhythm of the island’s days.

Their colours ignite the imagination; their calls stir memory; their presence offers reassurance that nature still breathes alongside humanity. For conservation biologist Rajika Gamage, these winged lives are more than fleeting beauty—they are a lifelong calling.

Now, after years of patient observation, artistic collaboration, and scientific dedication, Gamage’s latest book, An Illustrated Field Guide to the Fauna of Sri Lanka – Birds, is set to reach readers when it hits the market on March 6.

The new edition promises to become one of the most comprehensive and visually rich bird guides ever produced for Sri Lanka.

Speaking to The Island, Gamage reflected on the inspiration behind his work and the enduring fascination birds hold for people across the country.

“Birds are an incredibly diverse group,” he said. “Their bright colours, distinct songs and calls, and showy displays contribute to their uniqueness, which is appreciated by all bird-loving individuals.”

Birds, he explained, occupy a special place in the natural world because they are among the most visible forms of wildlife. Unlike elusive mammals or secretive reptiles, birds share human spaces openly.

“Birds are widely distributed in all parts of the globe in large enough populations, making them the most common wildlife around human habitations,” Gamage said. “This offers a unique opportunity for observing and monitoring their diverse plumage and behaviours for conservation and recreational purposes.”

This accessibility has made birdwatching one of the most popular forms of wildlife observation in Sri Lanka, attracting everyone from seasoned scientists to curious schoolchildren.

A remarkable island of avian diversity

Despite its small size, Sri Lanka possesses extraordinary bird diversity.

According to Gamage, the country’s geographic position, varied climate, and diverse habitats—from coastal wetlands and rainforests to montane cloud forests and dry-zone scrublands—have created ideal conditions for birdlife.

“Sri Lanka is home to a rich diversity of birdlife, with a total of 522 bird species recorded in the country,” he said. “These species are spread across 23 orders, 89 families, and 267 genera.”

Of these, 478 species have been fully confirmed. Among them, 209 are breeding residents, meaning they live and reproduce on the island throughout the year.

Even more remarkable is Sri Lanka’s high level of endemism.

“Thirty-five of these breeding resident species are endemic to Sri Lanka,” Gamage noted. “They are confined entirely to the island, making them globally significant.”

These endemic species—from forest-dwelling flycatchers to vividly coloured barbets—represent evolutionary lineages shaped by Sri Lanka’s long geological isolation and ecological uniqueness.

In addition to resident birds, Sri Lanka also serves as a seasonal refuge for migratory species traveling thousands of kilometres.

“There are regular migrants that arrive annually, as well as irregular migrants that visit less predictably,” Gamage explained. “Vagrants, birds that appear outside their typical migratory routes, have also been spotted occasionally.”

Such unexpected visitors often generate excitement among birdwatchers and scientists alike, providing valuable insights into migration patterns and environmental change.

Rajika Gamage

A guide born from passion and necessity

The new field guide represents the culmination of years of research and builds upon Gamage’s earlier publication, which was released in 2017.

“The stimulus for this bird guide was due to the success of my first book,” he said. “This new edition aims to facilitate identification and provide an idea of what to look for in observed habitats or regions.”

The book is designed not merely as a scientific reference but as an accessible companion for anyone interested in birds. Its structure reflects this dual purpose.

“The first section is dedicated to the introduction, geography, and life history of Sri Lankan birds,” Gamage explained. “The second section is the main body of the guide, which illustrates 532 species of birds.”

Each illustration has been carefully crafted in colour to capture the distinctive plumage of each species.

“All illustrations are designed to show each bird’s significant and distinct plumage,” he said. “Where possible, the breeding, non-breeding, and juvenile plumages are provided.”

This attention to detail is especially important because many birds change appearance as they mature.

“Some groups, especially gulls, display many plumages between juveniles and adults,” Gamage noted. “Many take several years to develop full adult plumage and pass through semi-adult stages.”

By illustrating these stages, the guide helps birdwatchers avoid misidentification and deepen their understanding of avian development.

New discoveries and evolving science

One of the most exciting aspects of the new edition is its inclusion of newly recorded species and updated scientific classifications.

“Changes in the bird list of Sri Lanka, especially newly added endemic birds such as the Sri Lankan Shama, Sri Lanka Lesser Flameback, and Greater Flameback, are now included,” Gamage said.

Scientific names and classifications are not static; they evolve as researchers learn more about genetic relationships and species boundaries. The guide reflects these changes, ensuring it remains scientifically current.

The book also incorporates conservation status information based on the latest National Red Data Report and global assessments.

“The conservation status of Sri Lankan birds, as listed in the 2022 National Red Data Report and the global Red Data Report, are included,” Gamage said.

This information is vital for conservation planning and public awareness, highlighting which species face the greatest risk of extinction.

The guide also documents rare and accidental visitors, including species such as the Blue-and-white Flycatcher, Rufous-tailed Rock-thrush, and European Honey-buzzard.

“These represent accidental visitors and newly recorded vagrants,” Gamage said. “Altogether, the first edition offers some 25 additional species, all illustrated.”

Art and science in harmony

Unlike many field guides that rely heavily on photographs, Gamage’s book emphasises detailed illustrations. This choice reflects the unique advantages of scientific art.

Illustrations can emphasise diagnostic features, eliminate distracting backgrounds, and present birds in standardised poses, making identification easier.

“The principal birds on each page are painted to a standard scale,” Gamage explained. “Flight and behavioural sketches are shown at smaller scales.”

The guide also includes descriptions of habitats, distribution, nesting behaviour, and alternative names in English, Sinhala, and Tamil.

“The majority of birds have more than one English, Sinhala, and Tamil name,” he said. “All of these are included.”

This multilingual approach reflects Sri Lanka’s cultural diversity and ensures the guide is accessible to a wider audience.

A tool for conservation and connection

Beyond its scientific value, Gamage believes the book serves a deeper purpose: strengthening the bond between people and nature.

By helping readers identify birds and understand their lives, the guide fosters appreciation and responsibility.

“This field guide aims to facilitate identification and provide a general introduction to birds,” he said.

In an era of rapid environmental change, such knowledge is essential. Habitat loss, climate change, and human activity continue to threaten bird populations worldwide, including in Sri Lanka.

Yet birds also offer hope.

Their presence in gardens, wetlands, and forests reminds people of nature’s resilience—and their own role in protecting it.

Gamage hopes the guide will inspire both seasoned ornithologists and beginners alike.

“All these changes will make An Illustrated Field Guide to the Fauna of Sri Lanka – Birds one of the most comprehensive and accurate guides available within Sri Lanka,” he said.

A lifelong devotion takes flight

For Rajika Gamage, birds are not merely subjects of study—they are companions in a lifelong journey of discovery.

Each call heard at dawn, each silhouette glimpsed against the sky, each feathered visitor from distant lands reinforces the wonder that first drew him to ornithology.

With the release of his new book on March 6, that wonder will now be shared more widely than ever before.

In its pages, readers will find not only identification keys and scientific facts, but also something more enduring—the story of an island, told through wings, colour, and song.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Letting go: A Buddhist perspective

Buddhism, one of the world’s oldest religions, offers profound insights into the nature of existence and the ways we can alleviate our suffering. As one of the world’s most profound spiritual traditions, it offers a transformative solution: the art of letting go. Unlike simply losing interest in things or giving up, letting go in Buddhism is about liberation, releasing ourselves from the chain of attachment that prevents us from experiencing true peace and happiness. Letting go is a profound philosophical concept in Buddhism, deeply intertwined with an understanding of suffering, attachment, and the nature of reality. This philosophy encourages us to release our grip on desires, attachments, and on what we hold dear- whether relationships, material goods, or even their identities, ultimately leading to greater peace and enlightenment. Our tendency to cling tightly to the various aspects of life leads to a significant source of stress. We tend to grasp at things, perceiving them as solid and permanent, yet much of what we hold onto is transient and subject to change. This mistaken belief in permanence can trap us in cycles of worry, fear, and anxiety.

The challenge of letting go is especially evident during difficult periods in life. We may find ourselves ruminating over lost opportunities, failed relationships, and unmet expectations. Such thoughts can keep us ensnared in emotions like hurt, guilt, and shame, hindering our ability to move forward. By holding onto the past, we often prevent ourselves from embracing the present and future.

At the heart of Buddhist practice lies the concept of letting go, often encapsulated in the term “non-attachment.” Letting go is a crucial concept in both Buddhism and Christianity, emphasising the release of attachments that bind us and contribute to our suffering. At its core, letting go is about finding freedom from desires and acknowledging that both relationships and material possessions are fleeting and transient.

In Buddhism, letting go, or non-attachment, is fundamental for achieving inner peace. The First Noble Truth acknowledges that life is filled with suffering, often rooted in our cravings and attachment to things. The Second Noble Truth teaches that by letting go of this craving, we can transcend the cycles of life and attain enlightenment.

Spiritually, Buddhism emphasises the impermanence of all things (annica). We tend to cling to people, experiences, and even our identities, but everything is fleeting. Recogniing this helps us appreciate the present moment and fosters compassion. Instead of allowing attachments to cloud our relationships, letting go encourages us to engage with others without judgment or expectation, fostering deeper connections.

Philosophically, Buddhism challenges the notion of a permanent self (anatta) that is often the focus of human attachment. It teaches that our identity is not a fixed entity but a collection of experiences and perceptions in constant flux. Understanding this can help us see the futility of clinging to desires and identities, paving the way for a liberated state of being built on wisdom cultivated through meditation and mindfulness.

From a psychological standpoint, letting go can significantly improve our emotional health and well-being. Attachment often breeds fear, anxiety, and stress, while non-attachment promotes resilience and adaptability. When we embrace the idea of impermanence, we become more capable of handling life’s challenges without being overwhelmed. Mindfulness—being present and accepting our emotions without judgment—allows us to process difficult feelings constructively, making it easier to let go of what we cannot control.

Letting go is also an essential concept in Christianity, which emphasises surrender and trust in God. Biblical teachings encourage believers to let go of worries and anxieties, placing their faith in divine providence. For instance, verses like Matthew 6:34 remind individuals not to be anxious about tomorrow, but to focus on the present. By surrendering our burdens to God, we find peace and freedom from the weight of excessive attachment.

Moreover, both traditions highlight the importance of community. In Buddhism, the sangha, or community of practitioners, supports individuals on their journeys toward non-attachment. Similarly, the Christian community encourages believers to lean on one another for support, fostering a sense of belonging and shared faith that helps mitigate the loneliness that comes with attachment.

Ultimately, the concept of letting go serves as a powerful antidote to suffering in both Buddhism and Christianity. By embracing impermanence, cultivating wisdom, and practising mindfulness or faith, individuals can experience profound liberation. In our chaotic world, the principles of letting go offer a clear path toward inner peace, fulfilment, and deeper connections with ourselves, others, and the divine.

Buddhism explores the profound concept of letting go, providing valuable insights into the human experience and pathways to alleviating suffering. Rooted in one of the world’s oldest spiritual traditions, Buddhism presents letting go as a transformative practice, distinct from mere disengagement or giving up. Instead, it encompasses liberation from the chains of attachment that hinder us from experiencing genuine peace and happiness. Christianity too explore this profound concept in its teachings

At the core of Buddhist philosophy lies the idea of non-attachment, which encourages individuals to free themselves from desires and possessions, ultimately leading to tranquility and enlightenment. Letting go is intertwined with an understanding of suffering, attachment, and the transient nature of existence. This philosophy instructs us to relinquish our grip on what we hold dear—whether relationships, material goods, or even our identities—recognising that these are impermanent.

Buddhism’s First Noble Truth acknowledges that life inherently involves suffering, often stemming from our cravings and attachments. The Second Noble Truth reveals that overcoming this craving is key to transcending the cycles of life and achieving enlightenment. Emphasising the impermanence of all things, Buddhism invites us to appreciate the present moment and fosters compassion by helping us detach from fixed identities and experiences. This awareness enriches our relationships, allowing us to connect with others free from judgment or expectation.

Philosophically, Buddhism challenges the notion of a static self (anatta), asserting that our identity is not a fixed concept but rather a fluid collection of experiences. Recognising this notion helps highlight the futility of clinging to desires and identities, opening the door to a liberated existence founded on wisdom cultivated through meditation and mindfulness practices.

From a psychological perspective, the act of letting go can significantly enhance emotional health and well-being. Attachment often fuels fear, anxiety, and stress, while embracing non-attachment cultivates resilience and adaptability. By accepting impermanence, we equip ourselves to face life’s challenges with greater ease. Practicing mindfulness—being present and accepting emotions without judgment—further facilitates the process of releasing what is beyond our control.

In Christianity, the theme of letting go is also prominent, emphasizing surrender and trust in God. Scripture encourages believers to release their worries and anxieties by placing their faith in divine providence. For example, Matthew 6:34 advises individuals to focus on the present rather than fret over the future. By surrendering our burdens to God, we can experience relief from the weight of excessive attachment.

Both traditions underscore the significance of community in supporting the journey of letting go. In Buddhism, the sangha, or community of practitioners, encourages the pursuit of non-attachment. Likewise, Christian fellowship fosters belonging and shared faith, helping believers lean on one another for strength and mitigating the loneliness that can arise from attachment.

Ultimately, the concept of letting go serves as a powerful antidote to suffering in both Buddhism and Christianity. Embracing impermanence, nurturing wisdom, and practising mindfulness or trust can lead individuals toward profound liberation. In an increasingly chaotic world, the principles of letting go illuminate a pathway to inner peace, fulfilment, and deeper connections with ourselves, others, and the divine. By understanding and embodying this philosophy, we can navigate life’s complexities with grace and openness.////Buddhism delves into the profound concept of letting go, offering valuable insights into the human experience and pathways to alleviating suffering. As one of the world’s oldest spiritual traditions, Buddhism presents letting go as a transformative practice that goes beyond mere disengagement or resignation. It represents liberation from the chains of attachment that prevent us from experiencing true peace and happiness. Similarly, Christianity explores this profound concept in its teachings.

At the heart of Buddhist philosophy is the idea of non-attachment, which encourages individuals to free themselves from desires and possessions, ultimately leading to tranquility and enlightenment. Letting go is closely related to an understanding of suffering, attachment, and the impermanent nature of existence. This philosophy guides us to loosen our hold on what we cherish—be it relationships, material possessions, or even our own identities—recognizing that everything is transient. Through this understanding, we can cultivate a deeper sense of peace and fulfillment in our lives.

BY Dr. Justice Chandradasa Nanayakkara

BY Dr. Justice Chandradasa Nanayakkara

Features

Brilliant Navy officer no more

Rear Admiral Udaya Bandara, VSV, USP (retired)

This incident happened in 2006 when I was the Director Naval Operations, Special Forces and Maritime Surveillance under then Commander of the Navy Vice Admiral Wasantha Karannagoda. Udaya (fondly known as Bandi) was a trusted Naval Assistant (NA) to the Commander.

We were going through a very hard time fighting the LTTE Sea Tigers’ explosive-laden suicide boats that our Fast Attack Craft (s) and elite SBS’ Arrow Boats encountered in our littoral sea battles.

Brilliant Marine Engineer Commander (then) Chaminda Dissanayake, who was known for his “out of the box” thinking and superior technical skills on research and development, met me at my office at Naval Headquarters and showed me a blueprint of an explosive- laden remotely controlled small boat.

Udaya’s Naval Assistant’s office was next to mine, the Director Naval Operations office. Both places are very close to the Navy Commander’s office. I walked into Bandi’s office with Commander Dissa and showed this blueprint a brilliant idea. Being a Marine Engineer “par excellence”, Bandi immediately understood the great design. I urged him to brief the Commander of the Navy with Commander Dissa.

My burden was over! Bandi took over the project and within a few weeks we tested our first prototype “Explosive-laden Remotely Controlled arrow boat “at sea off Coral Cove in the Naval Base Trincomalee. It was a complete success.

This remotely controlled boats went out to sea with our SBS arrow boats fleet and had devastating effects against LTTE suicide boats and their small boats fleet. Thanks, Bandi, for your contribution. The present-day Admiral of the Fleet used to tell us during those days “you cannot buy a Navy – you have to build one”!

We built our own small boats squadrons at our boat yards in Welisara and Trincomalee to bring LTTE Sea Tigers. The Special Boats Squadron (SBS) and rapid action boats squadron (RABS) being so useful with remotely controlled explosive-laden arrow boats to win sea battles convincingly.

Bandi used to say, “Navy is a technical service and we should give ALL SRI LANKA NAVY OFFICERS FIRST A TECHNICAL DEGREE AT OUR ACADEMY (BTec degree).” That idea did not receive much attention here, but the Indian Navy—Bandi graduated as a Marine Engineer- at Indian Navy Engineering College SLNS Shivaji in Lonavala, Pune, India— understood this idea well over two decades ago. Indian Navy Commissioned their new Naval Academy at Ezhimala (in Kerala State) which is the largest Naval Academy in Asia (Campus covers area of 2,452 acres) starts its Naval officers training with a BTech degree, regardless of what branch of the navy one joined.

Bandi’s technical expertise was not limited to SLN. He was the pioneer of “Mini – Hydro Power projects” in Sri Lanka. When I was a young officer, he urged me to invest some money in one of these projects and advised me “Sir! as long as water flows through turbines, you will get money from the CEB, which is always short of electricity”. I regret that I did not heed Bandi’s advice.

When he worked under me when I was Commander Southern Naval Area, as my senior Technical Officer, I observed pencil marks on walls of his chalet and I inquired from him what they were. He said it was the result of his “pencil shooting training”, a drill Practical Pistol Firers do to improve their skills. He used to practice “draw and fire” drills and pencil shooting drills late into nights to be a good Practical Pistol firer in Sri Lanka Navy team. He didn’t stop at that. He represented Sri Lanka National Practical Pistol Firing team and won International Championships.

As the Officer in charge of Technical Training in the Navy, he worked as Training Commander to train Royal Oman Navy Engineering Artificers in Sri Lanka, especially on Fast Attack Craft Main Engine Overhauls. The Royal Oman Navy Commander was so impressed with the knowledge acquired by Artificers that he donated money for the construction of a four-storey accommodation building for Sri Lanka Navy Naval and Maritime Academy, Trincomalee now known as “Oman Building”. The credit for this project should go to Bandi.

Bandi’s wife was a senior Judge of Kegalle High Court, and she retired a few years ago. Their only child, a son studied at the British School, Colombo and followed in his mother’s footsteps became a lawyer. Bandi was so much attached to his family and very proud of his son’s accomplishments.

When Bandi was due to retire in 2016 as a Rear Admiral and Director General Training, after distinguished service of 34 years, and reaching retirement age of 55 years, I requested him to serve for some more years after mobilising him into our Naval Reserve Force. He had other plans. He wanted to take his mini-Hydro Power projects to East African countries.

His demise after a very brief illness at age of 64 years was a shock to his family and friends. His funeral was held on Feb. 27 with Full Military Honors befitting a Rear Admiral at his home town Aranayake.

Dear Bandi, the beautiful Sri Lanka Navy, Naval and Maritime Academy in Trincomalee, which was built with your efforts will serve for Sri Lanka Navy Officer Trainees and sailors for a very long time and remember you forever.

May dear Bandi attain the supreme bliss of Nirvana!

Naval and Maritime Academy, Trincomalee

By Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc

(Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defence Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd,

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation,

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPrime Minister Attends the 40th Anniversary of the Sri Lanka Nippon Educational and Cultural Centre

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoDottin out obstructing the field as Sri Lanka clinch series

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features5 days ago

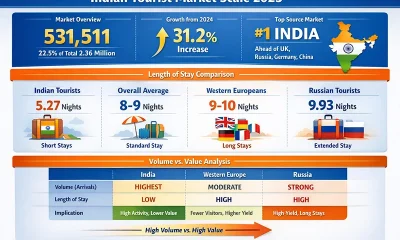

Features5 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoFuture must be won

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth