Life style

Amphibians going extinct in SL at a record pace

by Ifham Nizam

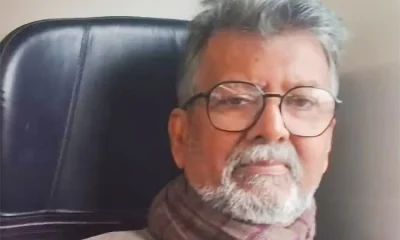

Sri Lanka holds the record for nearly 14 per cent of the amphibian extinctions in the world. In other words, of the 130 amphibian extinctions known to have occurred across the globe, 18 extinctions (14 per cent) have occurred in Sri Lanka, says Dr. Anslem de Silva, widely regarded as the father of Herpetology in the country. Speaking to The Sunday Island, the authors of a news book on amphibians, said that this is one of the highest number of amphibian extinctions known from a single country. Some consider this unusual extinction rate to be largely the result of the loss of nearly 70 per cent of the island’s forest cover. Dr. Anslem de Silva, Co-Chairman, Amphibian Specialist Group, International Union for the Conservation of Nature/Species Survival Commission (IUCN/SSC), together with two academics, Dr. Kanishka Ukuwela, Senior Lecture at Rajarata University, Mihintale who is  also associated with IUCN/SSC and Dr. Dillan Chaturanga, Lecture at Ruhuna University, Matara had authored this most comprehensive book on amphibians running to nearly 250 pages released last week. The prevalent levels of application of agrochemicals up to few months back, especially in rice fields, and vegetable and tea plantations, have increased over the past three decades. Similarly, the release of untreated industrial wastewater to natural water bodies has intensified. As a consequence, many streams and canals have become highly polluted, they say. The use of pesticides directly decreases the insect population, an important source of food for amphibians. Furthermore, these pollutants can easily make the water in paddy fields and the insects on which the amphibians feed toxic or increase the nitrogen content of the water. The highly permeable skins of amphibians would certainly cause them to be directly affected by these, they add. Amphibian mortality due to road traffic is a widespread problem globally that has been known to be responsible for population reductions and even local extinction in certaininstances. In Sri Lanka, amphibian mortalities due to road traffic are highly prevalent on roads that serve paddy fields, wetlands and forests. Further, they are especially intensified on rainy days when amphibian activity is high, the book explains. Recent studies indicate that amphibian road kills are exacerbated in certain national parks in the country due to increased visitation. According to recent estimates, several thousand amphibians are killed annually due to road traffic.

also associated with IUCN/SSC and Dr. Dillan Chaturanga, Lecture at Ruhuna University, Matara had authored this most comprehensive book on amphibians running to nearly 250 pages released last week. The prevalent levels of application of agrochemicals up to few months back, especially in rice fields, and vegetable and tea plantations, have increased over the past three decades. Similarly, the release of untreated industrial wastewater to natural water bodies has intensified. As a consequence, many streams and canals have become highly polluted, they say. The use of pesticides directly decreases the insect population, an important source of food for amphibians. Furthermore, these pollutants can easily make the water in paddy fields and the insects on which the amphibians feed toxic or increase the nitrogen content of the water. The highly permeable skins of amphibians would certainly cause them to be directly affected by these, they add. Amphibian mortality due to road traffic is a widespread problem globally that has been known to be responsible for population reductions and even local extinction in certaininstances. In Sri Lanka, amphibian mortalities due to road traffic are highly prevalent on roads that serve paddy fields, wetlands and forests. Further, they are especially intensified on rainy days when amphibian activity is high, the book explains. Recent studies indicate that amphibian road kills are exacerbated in certain national parks in the country due to increased visitation. According to recent estimates, several thousand amphibians are killed annually due to road traffic.

Professor W. A. Priyanka, PhD (USA), Professor in Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Peradeniya says the need for a guide to the amphibian fauna of Sri Lanka is obvious, given the currently critical conditions endangering them. Amphibians are an attractive group of animals whose diversity has always sparked interest among the scientific community, creating a vast body of unanswered questions.However, the identification of amphibians has been a challenge due to the lack of a complete and informative guide. The comprehensive pictorial guide provided by the new book should thus be of great benefit to a better understanding of the unique and intriguing nature of these fascinating living beings.The authors have done an outstanding job in compiling this book. An introduction to the guide briefly describes the history, current status, threats and conservation information, along with interesting folklore associated with amphibians. With the clear and informative images, distribution maps and updated status of each species, this guide can easily be comprehended by experts and beginners in the field alike.”I firmly believe that this book will be very useful to undergraduate and postgraduate students in the fields of zoology, biology and environmental science, as well as researchers, wildlife managers and visitors,” Professor Priyanka added.The authors said that like their previous guide to the reptiles of Sri Lanka, A Naturalist’s Guide to the Reptiles of Sri Lanka (de Silva & Ukuwela, 2017, 2020), this book is intended for both naturalists and visitors to Sri Lanka, providing an introduction to the amphibians found here. It features all the extant species of amphibian in this country with colour photographs and quick and easy tips for identification. At the time of writing, 120 species have been recorded within the country and ongoing taxonomic work is certain to add more to this impressive list in the next few years.This guide provides a general introduction to the amphibians of Sri Lanka, a profile of the physiographic, climatic, and vegetation features of the island, key characteristics that can be used in the identification of amphibians and descriptions of each extant amphibian species.Additionally, it presents information on amphibian conservation here and a brief introduction to folklore and traditional treatment methods for combating poisoning due to amphibians in this country. The species descriptions are arranged under their higher taxonomic groups(orders and families), and further grouped in their respective genera.The descriptions are organized in alphabetical order by their scientific names. Every species covered is accompanied by one or more colour photograph of the animal. Each account includes the vernacular name in English, the current scientific name, the vernacular name in Sinhala, a brief history of the species, a description with identification features, and details of habitat, habits and distribution (both here and outside the country).Key external identification features of the species, such as body form, skin texture and coloration, are provided, to help in the quick identification of an animal in the field.It must be noted that according to Sri Lanka’s wildlife laws, amphibians cannot be captured or removed from their natural habitats without official permits, which must be obtained in advance from the Department of Wildlife Conservation.Sri Lanka is home to an exceptional diversity of amphibians. Currently, the island nation boasts of 112 species of amphibians of which 98 are restricted to the country. However, nearly 60 per cent of this magnificent diversity is threatened with extinction. To make matters worse, very little attention is paid by the conservation authorities or the public. The last treatise on the subject was published 15 years ago. However, many changes have taken place since then and hence an updated compilation was a major necessity. This book by the three authors intends to popularize the study of amphibians by the general public by filling this large void. Historical aspects

Sri Lanka is one of the few countries in the world where conservation and protection of its fauna and flora has been practiced since pre-Christian times. There is much archaeological, historical and literary evidence to show that from ancient times amphibians have attracted the attention of the people of this island.

This is evident by the discovery of an ancient bronze cast of a frog (see photo) discovered during excavations conducted by the Department of Archaeology and the Central Cultural Fund. Strati-graphic evidence from the excavation sites indicate that these objects belong to the sixth to eighth centuries AD (Anuradhapura and Jetavanārāma museum records). Beliefs that feature the ‘good’ qualities of frogs and association with nature. These beliefs have some positive effects on the conservation of amphibians, perhaps one reason that Sri Lanka harbours a diverse assemblage of frogs. Absence of frogs and toads in agricultural fields indicates impending crop failure, it is believed.

The authors have specially thanked Managing Director John Beaufoy of John Beaufoy Publishing Ltd, for publishing many books promoting Sri Lanka diversity.

Life style

Cinnamon Life at City of Dreams receives prestigious five-Star certification from SLTDA

Cinnamon Life that has re-defined Colombo’s skyline added another accolade to its journey as it officially received its five star certification placing it among the most distinguished luxury properties in Sri Lanka’s hospitality landscape.

Receiving the five star classification is a significant achievement for any hotel but Cinnamon Life – the flagship of Sri Lanka’s most ambitious integrated lifestyle development, the accolade carries exceptional meaning. The recognition follows a rigorous evaluation of service standards,facilities,and operational excellence,underscoring the property’s commitment to delivering world class guest experiences

– Cinnamon Life at City of Dreams has been officially awarded the esteemed Five-Star Certification by the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), underscoring its status as a landmark in Sri Lanka’s hospitality landscape and a benchmark for excellence in the region.

As South Asia’s largest and first fully integrated resort, Cinnamon Life at City of Dreams represents a transformative investment in Sri Lanka’s tourism and leisure economy. Developed by John Keells Holdings PLC with a historic USD 1.2 billion investment – the largest private development in the country – the resort has reshaped Colombo into a premier destination for luxury travel, entertainment, world-class events, and international business.

A hallmark of the property is its extensive event and convention infrastructure, featuring over 160,000 sq. ft. of versatile, high-spec event space. With five signature ballrooms, cutting-edge technology, and three exceptional outdoor venues offering panoramic views of the ocean and the Colombo skyline, Cinnamon Life has established itself as an unrivalled hub for global conferences, high-profile celebrations, and corporate gatherings for both local and international travellers.

“We are deeply honoured to receive this Five-Star Certification from the Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority,” said Sanjiv Hulugalle, CEO and General Manager of Cinnamon Life at City of Dreams. “This recognition reflects our unwavering commitment to world-class service, guest centric innovation, and the elevated experiences that define Cinnamon Life. Our aspiration is to set new standards for luxury, leisure, and MICE tourism in the region, while supporting Sri Lanka’s positioning on the global stage.”

The Five-Star Certification further cements Cinnamon Life at City of Dreams as one of Sri Lanka’s foremost luxury destinations. With its two luxury hotels, curated signature dining concepts, immersive entertainment arenas, and a vibrant retail and lifestyle precinct, the resort offers an unparalleled blend of hospitality, lifestyle, and experiences under one iconic address.

The certification was presented at Cinnamon Life, attended by senior leadership from SLTDA and Cinnamon Life, members of the hospitality industry, and media representatives. The event celebrated this milestone achievement and marked a significant step forward in elevating Sri Lanka’s luxury hospitality offering.

About City of Dreams

City of Dreams is Sri Lanka’s largest and most ambitious integrated resort, redefining Colombo’s skyline as a symbol of modern luxury and innovation. Designed as a “city within a city,” the destination offers 800 luxury rooms and suites, with 687 at Cinnamon Life and 113 at NUWA, complemented by a diverse selection of 13 restaurants and bars that showcase global cuisines alongside Sri Lanka’s rich culinary heritage. Adding to its appeal is a vibrant mix of high-end retail, Sri Lanka’s premier entertainment arena, a shopping mall, office towers, and luxury residences. This integrated ecosystem enables delegates to stay, work, meet, dine, shop, and celebrate seamlessly under one roof, delivering unmatched convenience and engagement.

Life style

Tourist Board reassures: Sri Lanka safe, open and ready

Cyclone Ditwah carved a trail of devastation as it roared across many regions, unleashing a deluge that transformed the entire towns into destruction. This is one of the most unforgiving storms in recent years – bringing torrential rains, violent winds and a trail of destruction that left thousands displaced in a matter of hours. Homes swept away, roads disappeared and families were forced to flee.

Yet beneath the chaos and loss, a quiet resilience emerged, communities rallied, rescue teams worked around the clock to restore roads, relocate displaced families and ensure the safety of the tourists.

Now with waters slowly receding, the full story of Ditwah’s impact is only a beginning to unfold – a story of heartbreak, survival and the long road to rebuilding.

Cyclone Ditwah delivered a sharp blow to the tourism sector within hours and days, disrupting travel routes, damaging coastal routes, and forcing authorities to reassess visitor safety. as hoteliers,tour operators,and government agencies worked round the clock to stabilise operations.The industry soon reassured global travellers that the island remains open and resilient.Rescue teams were deployed immediately, working around the clock to evacuate families and restore essential services.

While several areas experienced significant damages, authorities assured that key tourism zones remain safe and operational.

A press conference was summoned by the Ministry of Tourism and Foreign affairs, last week bringing together top officials, media and other hospitality partners to address growing public concern,assure international travellers and outline the immediate steps taken to ensure safety across all tourist zones. The Deputy Minister of Tourism, Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe and Chairman of SLTPB, Buddhika Hewawasam stepped forward to present a clear,unified message that Sri Lanka remains safe, prepared and committed in protecting the visitors. They calmed anxieties,dispelled myths,rumours and dispelled misinformation and revealed the coordinated efforts of the government to keep the hospitality industry unshaken.

A press conference was summoned by the Ministry of Tourism and Foreign affairs, last week bringing together top officials, media and other hospitality partners to address growing public concern,assure international travellers and outline the immediate steps taken to ensure safety across all tourist zones. The Deputy Minister of Tourism, Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe and Chairman of SLTPB, Buddhika Hewawasam stepped forward to present a clear,unified message that Sri Lanka remains safe, prepared and committed in protecting the visitors. They calmed anxieties,dispelled myths,rumours and dispelled misinformation and revealed the coordinated efforts of the government to keep the hospitality industry unshaken.

Tourism authorities pointed out even in the aftermath of Ditwah,the arrival of the cruise ship sent a powerful message. the ship’s docking underscored that Sri Lanka is safe . The arrival of this luxury cruise liner carrying hundreds of international passengers, was part of a regional voyage from Mumbai to Singapore. This was a symbolic moment unfolding at the harbour, it was a glimmer of hope in a week overshadowed by stormy clouds. The Tourism authorities reflected this arrival as a sign that confidence in Sri Lanka had not lost hope and showed Sri Lanka is steady,ready,and open.

The Deputy Minister of Tourism Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe in a speech marked by confidence and determination said. “Our teams have worked round the clock to ensure safety, restore access routes and support our travellers”.

Today I assured every traveller Sri Lanka is safe, Sri Lanka is open, and Sri Lanka is ready. He confirmed that all major coastal resorts from Negombo to Bentota remain fully operational. Cultural destinations such as Kandy, Dambulla, Kandy,Sigiriya, are now open. He further noted that national parks,including Yala, Udawalawe,Wilpattu had returned operations following rapid assessments. Our key tourist zones are open,accessible and operating under verified safety conditions. He assured that every tourist in the island was safe,

He praised the rescue teams who had worked round the clock, cleaning roads, supporting displaced families and ensuring tourism infrastructure remained intact. To the world I say please come visit, and explore. Our island stands tall and more ready than ever to welcome you. This is not just recovery, he concluded,this is resilience in action. Finally he stressed that Sri Lanka’s tourism sector had demonstrated structural resilience,operational continuity and readiness to maintain international confidence.

The Chairman of the SLTPB Buddika Hewawasam also briefed the media on the ongoing relief operations. He acknowledged the sharp blow and destruction but underscored the country’s resilience. We want to assure travellers that Sri Lanka remains safe. Our teams are on the ground, our infrastructure is being restored and our hospitality sector stands ready to welcome visitors as recovery unfolds.

He said “New the waters have receded, and Sri Lanka is ready to welcome the world. Cyclone Ditwah swept through the island with devastating force, but in its aftermath, a story of resilience, beauty and unwavering hospitality has emerged – one that travellers are invited to witness firsthand”.

For travellers, this is a chance to experience a Sri Lanka that is vibrant and sparkling with life where cultural heritage, natural beauty and warm hospitality blend. Cyclone Ditwah may have left a mark, but it could not dim the island’s radiance.

The Tourism sector is preparing to move forward with renewed emphasis on resilience, safety and rebuilding confidence among international travellers. Sri Lanka has weathered the storm and the world is already sailing back to its shores.

Life style

Championing mental health, rehabilitation, and social upliftment

Tiesh jewellery , announced a meaningful partnership with the Infinite Grace Foundation Sri Lanka, an organisation dedicated to transforming lives through love, dignity, purpose, and long-term social impact.

This collaboration marks a significant milestone as two Sri Lankan entities join hands to address some of the country’s most urgent and overlooked challenges, including mental health, drug addiction, prisoner rehabilitation, anti-human trafficking awareness, and the empowerment of estate communities.

Founded on the belief that “Every life deserves to be seen and loved,” the Infinite Grace Foundation symbolises hope, transformation, and inclusion. The Foundation works to extend a lifeline to those often ignored or marginalised, ensuring they are reminded that they are valued, loved, and never alone.

Their vision is deeply aligned to create a Clean Sri Lanka—not only in its physical environment, but in its hearts, minds, and communities. Through systemic intervention, awareness, and rehabilitation, the organisation aims to restore dignity, provide second chances, and help individuals reclaim their potential.

Stephanie Siriwardhana, Founder of the Infinite Grace Foundation and Brand Ambassador for Pure Gold by Tiesh

As part of its awareness and empowerment initiatives, Infinite Grace Foundation has launched the “I See You” campaign—an effort to recognise, support, and uplift individuals who have long been overlooked. Through this campaign, the foundation aims to promote year-round advocacy, encompassing mental health support, panel discussions, and collaborations with organisations and hotlines that support vulnerable groups across the island.

In support of this meaningful initiative, Tiesh has designed an exclusive jewellery collection created with intention and purpose. All proceeds from the collection will be donated directly to the Infinite Grace Foundation. The range features intricately crafted earrings, pendants, chains, rings, and more for women, as well as bracelets, cufflinks, lapel pins, and rings for men. Offered in diamonds, as well as gold and silver, each piece carries a profound message—that every life deserves to be seen, acknowledged, and loved.

With a legacy spanning more than two decades, Tiesh founded by Lasantha and Bryony De Fonseka, has become synonymous with innovation, excellence, and artistry in Sri Lanka’s jewellery landscape. Today, the family-run business is led by the next generation, with Directors Ayesh De Fonseka and Thiyasha De Fonseka continuing to uphold the brand’s commitment to integrity, community, and craftsmanship.

Stephanie Siriwardhana, Founder of the Infinite Grace Foundation and Brand Ambassador for Pure Gold by Tiesh, expressed the impact of this partnership: “This collaboration is special in many ways, and I’m truly grateful that a prestigious jeweller like Tiesh cares about communities that are often unseen—such as prisoners and estate workers. When you change one life, you change a family. When families transform, communities transform, and soon you change the nation. This initiative comes from a personal place. Many people struggle to ask for help, including myself. Through the ‘I See You’ campaign, we aim to provide support, raise awareness, and offer year-round mental health programs, alongside organisations and hotlines that are equipped to help victims and individuals in need. This partnership with Tiesh will be deeply impactful.”

The work of the Infinite Grace Foundation spans multiple critical pillars, including prison reforms, addiction rehabilitation, community education, vocational training, anti-human trafficking awareness, and mental health destigmatisation—all designed to create long-term, sustainable change across Sri Lanka.

Reflecting on the significance of the collaboration, Director of Tiesh, Ayesh De Fonseka, added, “Helping the community is rooted in our beliefs and upbringing. This partnership presented a meaningful opportunity to give back and support an important cause. We believe in second chances, and many individuals need guidance, care, and the opportunity to rebuild their lives. We are honoured to donate all profits from this collection. In the future, we hope to extend support further by offering job opportunities—whether in jewellery craftsmanship, box making, design, or other livelihood pathways.”

Through this partnership, Tiesh and Infinite Grace Foundation reaffirm their shared commitment to building a Sri Lanka where hope thrives, opportunities are equitable, and transformation is within reach for all.

For those wishing to support this initiative or explore the special collection, please visit the Tiesh showroom at 253 R. A. De Mel Mawatha, Colombo 03, or follow Tiesh on social media for updates and campaign information.

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGota ordered to give court evidence of life threats

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn awakening: Revisiting education policy after Cyclone Ditwah

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoCliff and Hank recreate golden era of ‘The Young Ones’

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoA national post-cyclone reflection period?