Opinion

The most dangerous moment

By Jayantha Somasundaram

“British Prime Minister Winston Churchill considered the most dangerous moment of the Second World War, and the one which caused him the greatest alarm, was when news was received that the Japanese Fleet was heading for Ceylon.” –The Most Dangerous Moment by Michael Tomlinson (1976) William Kimber, London.

It is 80 years since Ceylon, the British colony, came under attack from a Japanese armada on Easter Sunday 5th April 1942. The Second World War, which commenced in September 1939, was a distant war, with the theatre of war being initially Europe and North Africa. Commencing with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the defeat of British forces in Malaya, in January 1942, and the fall of Singapore in February, World War II entered the Indian Ocean, and its epicentre British Ceylon.

In British strategic perception, Fortress Singapore was the key to the protection of their colonies on the Indian Ocean littoral and the sea route to East Asia. With the fall of Singapore, the Indian Ocean became the central theatre of the War. In the Indian Ocean itself the fulcrum of maritime control rested in Ceylon and the Maldives. And this perception predated the Japanese entry into the War in December 1941.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had written to the Prime Ministers of Australia and New Zealand in August 1940, that in the event of Japan entering the War “we should also be able to base on Ceylon a battle cruiser and a fast aircraft carrier which, with Australian and New Zealand cruisers and destroyers… act as a very powerful deterrent.”

If the Japanese took Ceylon, the Maldives, the Seychelles and Christmas Island they could paralyse Allied shipping and resupply to its theatres globally, in Europe and in Asia. This included US shipments to the Soviet Union, via the Persian Gulf, and to China, via the Bay of Bengal. The Japanese could even ultimately link hands with the Germans, now advancing towards Cairo and Suez, in North Africa.

Vice-Admiral James Somerville, Commander of the Royal Navy’s (RN) Eastern Fleet, would later explain to Australia’s Minister of External Affairs, Dr Herbert Evatt, why he was not stationed in Western Australia, because “Ceylon flanks, or covers, all vital lines of communication to the Middle East, India and Australia,” while Australia, lying as it does at the end of a line of communication, was not the ideal location for protecting the Allied sea lanes across the Indian Ocean.

Ceylon’s Loyalty

At the outbreak of the War, Governor Andrew Caldecott wrote to the Colonial Office that the Ceylon National Congress dominated State Council had passed a resolution pledging loyalty to London, unlike the rebellious Indian National Congress in the more important British colony India. In June 1940 Caldecott went on to report to the Colonial Office that the only exception was the “left-wing Samajists (sic) … (who) have come out definitely anti-British.” And in September 1940 Caldecott went further telling the Colonial Office that “Ceylon’s loyalty to the Empire during the War which I assess at over 99 per cent…is due to…a high sentimental regard for the King’s Person and Throne.”

When Singapore fell on 15 February the Chiefs of Staff, ̶̶ the heads of the RN, the British Army and the Royal Air Force (RAF) ̶̶ asserted that “the basis of our general strategy lies in the safety of our sea communications for which secure naval and air bases are essential…Thus we must secure Ceylon…The loss of Ceylon will imperil our whole British War effort in the Middle East and Far East.”

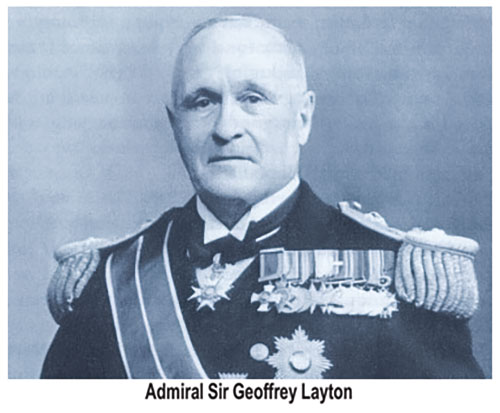

Meanwhile, on 26th February, Churchill suggested to the Commander-in-Chief India, General Archibald Wavell, who was on his way to Ceylon, to consider a Supreme Commander in overall charge of the Island in order to prevent a repetition of Singapore. On 5th March Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton was promoted Commander-in-Chief Ceylon, “London took the drastic step of subordinating the Island’s civil authorities to military command.” This was “Britain’s first experiment with unified command in an operational theatre.”

Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton

However, not only was Britain’s airpower in the Indian Ocean weak, they lacked an adequate maritime capability that could halt the advance of the expected Japanese carrier fleet. In fact Admiral Layton complained that “he was profoundly shocked … that Ceylon was virtually defenceless.”

In response “at the highest levels of war direction, Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff determined that Ceylon could not be allowed to fall and pumped in troops and aircraft while strengthening the Island’s shore defences and base infrastructure,” wrote Ashley Jackson in his 2018 book Ceylon at War 1939-1945. “The British Government was pulling out all the stops to reinforce the Indian Ocean and get troops and aircraft to Ceylon, but things took time to move across vast distances. It was a race against time.”

The Eastern Fleet

The First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound decided to withdraw the battleship HMS Warspite and the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable which were under the command of Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville from the Eastern Mediterranean and move them to Ceylon where Somerville would assume command of the Eastern Fleet. They were followed by four Revenge-class battleships and six destroyers.

By end March the Eastern Fleet included one light and two fleet carriers, five battleships, seven cruisers, 16 destroyers and seven submarines. The Eastern Fleet maintained seven shore bases including in India, the Maldives, Mauritius and Seychelles. Further, the RN’s East Indies Station was relocated to Colombo, with headquarters now at shore base HMS Lanka.

On 14th March, Admiral Layton ordered the evacuation from Ceylon of all non-residents, servicemen’s wives, European women and children; all except those doing essential work. While London rushed weapons, equipment and personnel to Ceylon, Admiral Layton strengthened the institutions and military capability of the Island’s defences.

Admiral Geoffrey Layton operated from the ‘Old’ Secretariat at Galle Face. Under his command were Admiral Somerville, Commander of the Eastern Fleet, Admiral Geoffrey Arbuthnot, Commander East Indies Station, General Officer Commanding Troops Major General Roland Inskip and Air Vice-Marshal John D’Albiac as Air Officer Commanding No. 222 Group. Capt Palliser RN was appointed Trincomalee Fortress Commander.

Troop reinforcements arriving in Ceylon included the 65th Heavy Anti Aircraft Regiment, 43rd Light Anti Aircraft Regiment and RAF personnel. 62 heavy and 100 light anti-aircraft guns along with barrage balloons, searchlights and radar units were established. This prompted the requisition of S. Thomas’ College Mount Lavinia for the accommodation of officers and St. Joseph’s College Maradana, for that of the men. “Schools and public buildings, hotels and houses were requisitioned to accommodate the new forces pouring into the island along with all that was needed to support them,” records Jackson.

Admiral Layton conceived, inspired and drove the hurried preparations, dictating to and overriding the key actors. Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the King’s cousin observed that even “the Governor is definitely under the Commander-in-Chief.”

Layton’s language and manner were rough quarter deck style. At the War Council meeting when a future Prime Minster John Kotelawala Minister of Communications and Works, responded to a query from Layton regarding a task with “the head overseer is having a lot of trouble with supplies;” Layton barked “then give him six on the backside!”

And when a future Governor-General, Civil Defence Commissioner Oliver Goonetilleke protested to Governor Andrew Caldecott that Layton had called him a black bastard, the Governor replied, “My dear fellow that is nothing to what he calls me!” Admiral Somerville explained to First Sea Lord Pound that “Layton takes complete charge of Ceylon and stands no nonsense from anyone.”

Battle for Ceylon

Meanwhile the Ratmalana Civil aerodrome was commandeered by the RAF and its runway doubled in length, the Colombo Museum became Army HQ, a flying boat base was developed at Koggala, fighter airbases opened in Dambulla, Minneriya and Vavuniya and a fleet air arm airbase at Katukurunda. Ashley Jackson, Professor of Imperial and Military History at King’s College London, in his 2009 paper War on the Home Front in Ceylon, writes “Ceylon was transformed from a (military) backwater into a key Allied military base.”

Number 258 Fighter Squadron withdrawn from Malaya and after seeing action in the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia) was re-equipped with Hurricanes from Karachi RAF Depot and reformed at Ratmalana on 30th March. It was then transferred to the new Colombo Racecourse RAF Base at Reid Avenue, with provision for the aircrew to sleep in the Grandstand during alerts and emergencies. Under Squadron Leader Peter Fletcher from Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) its pilots were from America, Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The RAF’s Fighter Operations Room was located at Bishop’s College, Kollupitiya.

The Battle for Ceylon was going to be a duel of skill, nerves and grit between the pilots of the approaching Japanese Carrier Fleet and the RAF fighter pilots defending Ceylon. The Air Order of Battle in Ceylon was:

Number 11 Bomber (Blenheim) Squadron at the Race Course, 30 Fighter (Hurricane) Sq at Ratmalana, 205 Maritime Reconnaissance (Catalina) Sq at Koggala, 258 Fighter (Hurricane) Sq at the Race Course, 261 Fighter (Hurricane) Sq at China Bay, 273 Fighter (Fulmar) Sq at China Bay, 788 Torpedo Bomber (Swordfish) Sq at China Bay, 803 Fighter (Fulmar) Sq Ratmalana and 806 Fighter (Fulmar) Sq Ratmalana.

Carrier borne aircraft on HMS Indomitable: 11 Sea Hurricanes, 10 Fulmar, 24 Albacore and 2 Swordfish.

On HMS Formidable: 21 Albacores and 12 Martlets

On HMS Hermes: 12 Swordfish.

The Eastern Fleet had 29 major warships, and they were divided into the Fast Division known as Force A and the Slow Division Force B. On 30th March well aware that the Japanese Fleet was in the Indian Ocean and heading for Ceylon, Admiral Somerville put to sea in the hope of intercepting the enemy fleet south of the Island. Somerville reasoned that Ceylon faced a night attack by Japanese aircraft, probably when the moon would be full on 01 April. But after two days of fruitless search the Eastern Fleet changed course on 3rd April and headed for Addu Atoll in the Maldives in order to replenish their stock of fuel and water.

(To be continued)

Opinion

Morning Star of Nursing Education in Sri Lanka

Chandra de Silva, 20th Death Anniversary

After a convulsive struggle for national liberation from British colonialism which tore the subcontinent apart, India gained its independence in 1947. Way ahead of Ceylon, on the cusp of this momentous event, it established a degree-awarding College of Nursing at the University of Delhi in 1946, a committee having visited and considered the best practices in nursing education in Canada, the USA, England and Scotland. It then carefully designed a course to meet the needs of India’s social and health requirements, and admitted its first batch of 13 students in July 1946, for a four-year BSc (Honors) degree in Nursing.

Soon after, they offered this advantage through a competitive interview to students from Ceylon.

In 1950, the year India adopted its first Republican Constitution, Chandra Samarasinghe was one of the three persons admitted to this course, and would go on to be the one who eventually introduced university education for Sri Lankan nurses in 1992, after a lifetime of campaigning.

When Chandra de Silva (nee Samarasinghe), much loved and respected by her students and colleagues alike, passed away 20 years ago on 28th January 2006, a former student wrote a moving tribute to her titled “The Morning Star of the World of Nursing Has Faded…” on the front page of the February 2006 issue of the magazine New Vision, a publication of the Graduate Nurses’ Foundation of Sri Lanka.

Describing Chandra as “the Nightingale of Sri Lanka”, a “most noble lady (Athi uththama kanthawa) filled with compassion”, “born for the good fortune of the nation” and “incomparable teacher-mother (guru mathawa) of hundreds of thousands of students”, the writer, Malini Ranasinghe, who was the President of the Graduate Nurses Foundation, confesses it is beyond her to set down in full Chandra’s life-long service of over 50 years to the profession. The magazine New Vision itself was one of Chandra’s many initiatives as was the encouragement for the Nursing Profession to obtain membership of the Sri Lanka Association of Professionals. Malini Ranasinghe promises in this heartfelt farewell, that Chandra’s legacy would be passed down the ages to each new batch of nursing students, to remain in their hearts through the course on the History of Nursing.

Chandra was Sri Lanka’s first Chief Nursing Education Officer (CNEO, now titled Director Nursing) at the Ministry of Health. She took up the pioneering role in 1967, having returned from Boston University, USA, after completing a Master’s degree in Education and Administration.

In her first year in the role, Chandra presented a comprehensive memorandum drawing the attention of the government of the day to the country’s need for a Bachelor’s degree in Nursing. She was the first to do so. It took decades before this dream came true, with Chandra having made several more proposals many years apart, before she was invited by a Canadian University in collaboration with the Open University of Sri Lanka (OUSL) to help set up the degree course in Nursing in 1992. Having spent most of her professional life in a battle to uplift the nursing profession in Sri Lanka to international standards, she was setting exam papers at the OUSL the day before she was admitted to hospital for kidney surgery, and passed away at the recovery unit. By then, she had seen not only several batches of undergraduate nurses don their robes, but also graduate nurses earn Master’s degrees with a PhD programme well on its way to being implemented.

When Delhi Built Bridges

It all started when three young ladies boarded a train with their Thomas Cooks travel documents, to Delhi in July 1950, having competed and won places at Delhi University to follow a BSc Honours degree, majoring in Nursing. Chandra Samarasinghe from Mahamaya College Kandy, dressed in a Kandyan Saree, Trixie Marthenesz from Ladies College and later Ananda College Colombo, and Shireen Packeer, also from Ananda College Colombo, in dresses, were the lucky ones selected, and became firm friends known as the “The Trio from Ceylon” at their university in India. They had “luxury accommodation” at their residential university campus at number 12, Jaswant Singh Road, New Delhi, and travelled everywhere on their bikes.

They had a blast during their four years there, not only completing their degrees but also able to experience the newly independent nation in transition, already forging a future for itself. Chandra continued to wear the Kandyan saree throughout her stay there, and when she had to introduce herself to the rest of the students, said “I am Chandra Samarasinghe from Kandy, in Lanka”, leaving a puzzled Trixie wondering why she didn’t say Ceylon. When they left the university after four years, the Principal, Dr. Margeretta Craig, O.B.E. told them “You three Ceylonese girls have been live wires!” They got on well with the staff including the Vice Principal Dr. Edith Buchanan, a Canadian from the Canadian Faculty of Nursing, who had an interesting experience with Chandra at their first encounter. When asked to explain the meaning of the term “prone position”, Chandra, always the first to offer an answer, piped up to say somewhat indelicately, “That’s the one with the backside up!” to giggles from the class. She was soon persuaded that “face-down” was a much more decorous way of saying it.

They sang and danced in the presence of Lady Edwina Mountbatten who graced the university’s annual concerts and had their names appear approvingly in the Indian newspaper report of the event. They were invited to Rashtrapati Bhavan in 1951 where they met India’s iconic first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Dr. Rajendra Prasad, the first President. They made friends with J. Wijetunga, author of ‘Grass for my Feet’ fame who lived only a short distance away from their hostel, who gave them free access to his pantry and taught them the cultural history of India and also of Sri Lanka. They travelled to places of interest including a long-desired visit to Shanthi Nikethan, having developed a love for Rabindranath Tagore’s work, and took photos in front of the Taj Mahal.

When they first arrived in Delhi, they were thrilled to meet another Sri Lankan student in the senior year who had known them from Ceylon, Viola Perera. Viola introduced them to her friends, one of whom on obtaining her PhD became the Principal of the College of Nursing, University of Delhi.

It was clear that their time at Delhi University left a deep impression on the girls. They were being trained to take over from the departing British, and to maintain the required standards as well as to develop them further. The sense of patriotic duty they saw in India made an impression on them. They also had plenty of fun, and Chandra was able to keep Ceylon’s end up when the beautiful Bengali voices of Indian students sang at their gatherings, having herself been voice-trained by Saranagupta Amarasinghe, and according to Trixie Marthenesz’s reminiscences in her book, ‘Those Delhi Days”, also by Ananda Samarakoon (p143).

A Worthy Battle Waged

Back in Ceylon, Chandra tried many times to introduce the educational opportunities she herself had obtained, to others in her profession. And yet, unlike India at Independence, Ceylon and later even Sri Lanka, was not ready to accept such progress easily. With the Health Ministry decision makers being male and mostly doctors, they ignorantly regarded the role of the nurse as a minor one, needing just “a pair of hands”. It may have involved some insecurity which masqueraded as good sense, at the cost to the country for many decades. As CNEO, Chandra battled through it all, rewriting the curriculum to bring it up to international standards, doing what she could to send Nurses overseas for training. And she kept presenting proposals for a BSc programme, which fell on deaf ears. Decades later, she was rewarded for her unwavering commitment to the cause when she was asked to start the BSc Nursing programme at the Open University of Sri Lanka (OUSL), which is now a great asset to the country, with other universities also offering it.

In 2004, two years before she passed away, the first publication of New Vision by the Graduate Nurses Foundation of Sri Lanka was presented to her. In the 2005 issue, they reproduced on the front page her keynote address at their AGM on the 31st of October 2004, at which she was Chief Guest.

Her speech recounts the painfully hard journey that the profession (and she herself) had to endure to raise it to its current status. Chandra recalls with sadness that the three-year Nursing Diploma did not entitle Sri Lankan nurses to pursue higher education, qualifying them only to follow a few courses at the Post Basic School of Nursing:

“I had to fight a very hard battle to keep the 3 year programme intact because there was a very serious effort to downgrade the three year programme to two years, a step that would have prevented our nurses from obtaining any acceptance and recognition in a foreign country. There was intense official and political pressure for a long time to effect this change but with the assistance of a few other Nursing Leaders this retrograde step was suppressed, perhaps forever. Such dangers can arise in the future too. The price we nurses have to pay, is eternal vigilance to challenge and suppress any effort to downgrade the standard of Nursing Education in Sri Lanka.”

She happily announced that at that stage, there were 200 BSc graduates and 25 who had obtained their Master’s degree, with two heading for their PhD. She defined the lack of access to higher education for nurses as a “human right denied”. She also declared that for the first time, there was agreement across all nursing services to propose a nursing degree at conventional universities, disclosing that this was the “first time such consensus has manifested in the Nursing Services”. She called upon nurses to retain this unity “at whatever cost” and just as in other professions such an engineering, law, medicine, “it was time to rectify this anomaly” and “work together to achieve this new dimension in Nursing Education.”

A Mother to More Than Her Own

As I write this memorial to honour my mother Chandra for her life of service and unwavering dedication to provide for others the education she herself received at two of the best universities in the world (Delhi and Boston), her determination and grace under pressure, I know why I have focused on her professional life rather than her personal one. It is because I grew up sensing that she was truly a mother to a larger family, of nursing students and professionals she was responsible for. She never turned away any of them coming over to her home for special help with their dissertation topics or applications for scholarships. She encouraged the senior nursing staff to follow the degree course and helped them complete it when they were discouraged. Some who recognized me at the counters in private hospitals came up to declare their gratitude to her for this specific gesture of help, because their employment prospects had expanded greatly with that.

Though infinitely patient, graceful and ladylike, my mother was a fighter. I saw how she never gave up on her ambitions for her profession, although she was hardly ambitious for herself. I saw her pain, and her determination to fight on in a hostile environment of male dominated bureaucracy.

I am eternally grateful to Aunty Trixie (Trixie Marthenesz, her fellow student at Delhi Uni) for writing a delightful little booklet called “Those Delhi Days” (Tharanjee Prints, Maharagama, 2009), recounting their time from 1950 to 1954 at the University of Delhi, with wonderful photographs of their 4-year journey as undergraduates, including at the annual concert in creative costumes and also on their holidays around India. An especially charming photo on the first page is the one on Convocation Day 1954, which shows Chandra, Trixie and Shareen together with a few of their batch mates wearing their robes with the distinctive Delhi Uni Cap. The book recalls in such delicious detail their time during such an exciting period in India, just two years after Independence from the British. I found some of the facts for this article from that book. Aunty Trixie, whom my mother drew in, together with Aunty Viola (Viola Perera, the senior student at Delhi University) talking them both out of retirement to begin the work of setting up a new department of Nursing at the Open University, writes in her book, of the young student Chandra who screamed at witnessing the death of their first patient in a hospital in India, bringing “half the ward to the scene”, but who then turned into “a leader among professional nurses in Sri Lanka” which appellation Trixie says “befitted her”.

I see that others have now taken the profession to new heights. Her students are now the warriors at the forefront of the battle for even further professional and pedagogical development. She would be proud. I like to believe that she was as much a guiding light as a Morning Star, softly glowing in the memories of those who knew her, inspiring them to never give up, and to do things with grace. That’s why I share these memories of my exceptional, beloved mother with all those nurses who have known her personally, her colleagues, lecturers and students in white who lined the path throwing jasmine blossoms at the vehicle taking her on her final journey through Kanatte, Colombo’s the main cemetery, and those who have and will come to know her, and the contribution she made to their profession, through the History of Nursing in Sri Lanka.

By Sanja de Silva Jayatilleka

Opinion

to pathi

Dharmasena Pathiraja’s eight death anniversary falls today

it is in loss and loneliness, one

finds words of solace, without which,

none may live or even die,

fling forging nouns,

into the far-flung corners

of birth and death, departing

from the beaten tracks of heavy tread.

dreams come and go,

in colour, as a contamination of the real,

the waking hours, a coming and going,

of departure and death

of bodies lined up shot,

in eelam, in lanka, or any other place.

the political is strained, half breathing,

lines the tongue with lashing words.

stories we tell our children

of war in words of peace,

and of peace in words there’s nothing to tell.

in silence, the quiet beat of the heart, strums louder and louder,

calling up the sound of waiting, for that time, when it is

all a matter of leaving, and now a matter for grieving,

living out the vanishing moments as limn, time pass, and

as our life foreshadowing death, not yet dreamt of,

but dreaded still.

in gaza, the children are gone forever

and it’s been a long journey, these forever years.

sumathy – january 2026

Opinion

Those who play at bowls must look out for rubbers

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake should listen at least to the views of the Mothers’ Front on proposed educational reforms.

I was listening to the apolitical views expressed by the mothers’ front criticising the proposed educational reforms of the government and I found that their views were addressing some of the core questionable issues relevant to the schoolchildren, and their parents, too.

They were critical of the way the educational reforms were formulated. The absence of any consultation with the stakeholders or any accredited professional organisation about the terms and the scope of education was one of the key criticisms of the Mothers’ Front and it is critically important to comprehend the validity of their opposition to the proposed reforms. Further, the proposals do include ideas and designs borrowed from some of the foreign countries which they are now re-evaluating in view of the various shortcomings which they themselves have encountered. On the subject, History, it is indeed unfortunate that it has been included as an optional, whereas in many developed countries it is a compulsory subject; further, in the module the subject is practically limited to pre-historic periods whereas Sri Lanka can proudly claim a longer recorded history which is important to be studied for the students to understand what happened in the past and comprehend the present.

Another important criticism of the Mothers’ Front was the attempted promotion of sexuality in place of sex education. Further there is a visible effort to promote trans-gender concepts as an example when considering the module on family unit which is drawn with two males and a child and two females and a child which are nor representative of Sri Lankan family unit.

Ranjith Soysa

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days ago‘Building Blocks’ of early childhood education: Some reflections