Features

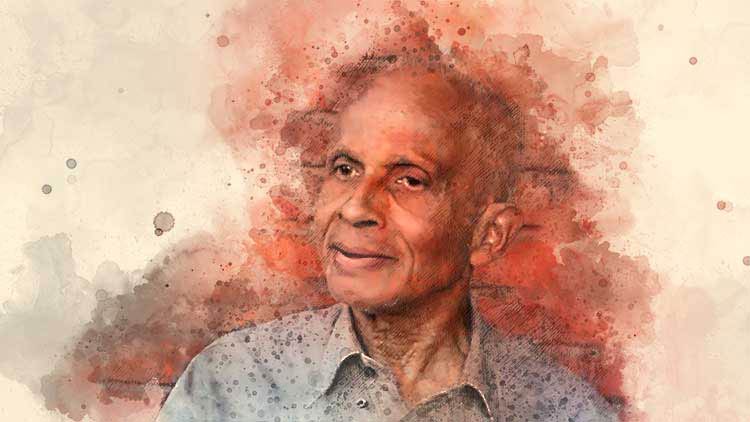

The Life and Times of Dr. Suman Fernando

By Ted Lo

Dr. Suman Fernando, a pioneering thinker in psychiatry, a fearless advocate for social justice in mental health, and the author of several important books on the subject passed away peacefully on January 31, 2025, at his home in London at the age of 93.

Although not widely known in Sri Lanka—the country of his birth, where he lived until the age of 17, and where his extended family continues to reside—Dr. Fernando was a much-respected figure in the field of mental health in the UK.

In 2012, shortly after turning 80, he was interviewed by his longtime friend and colleague, Ted Lo, about his passion for and lifelong dedication to mental health.

Below, we reproduce some of his reflections on the dilemmas of his early life which influenced him to choose mental health as his life’s commitment.

Early Life in Sri Lanka

Suman Fernando: I have always been interested in people’s cultures and backgrounds. Even as a child, I remember reading about African tribes and missionaries like Schweitzer—an interest in the exotic, I suppose. We didn’t use the term ‘multicultural’ then, but my early life was exactly that. Although I came from a Christian Sri Lankan Sinhalese background—my father was a Methodist, my mother an Anglican—our family was not particularly religious. My father often went to sleep in church. He was a doctor but also a politician in a somewhat left-wing party—a sort of armchair left-winger. Our home was frequently visited by people from different religious backgrounds. I remember my mother covering a chair with a white sheet when a Buddhist monk visited, and keeping the dogs away when a Muslim guest arrived, though I never understood why.

I was baptized and later ‘recognized’—a kind of confirmation at around 14 or 15. Methodists formed a small group of a few thousand members, mainly middle class, descended from early colonial-era converts.

For primary school, I attended a girls’ school called Ladies College, which admitted a few boys until the age of 12. It was run by missionaries. My secondary education was at Royal College, the only major state school in Colombo modeled after British public schools, with a principal and some teachers brought in from the UK. Established in 1835—just 20 years after Britain subjugated the country—it soon became a prestigious institution for the emerging middle class. Every morning, we had an assembly with readings from different scriptures—Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu or even secular literature—followed by classroom discussions.

Despite its multicultural setting, education was conducted entirely in English. Speaking Sinhalese or Tamil at school was discouraged; those languages were reserved for communicating with servants. This bred a sense of resentment, one my father often commented on. He criticized the way we were taught to look down on local languages and customs, yet he himself dressed in the manner of what the British called a ‘Westernized Oriental Gentleman’—the origin of the term ‘Wog,’ later used pejoratively in Britain. The British encouraged locals to imitate them, yet simultaneously despised those who did.

Sri Lankan society was deeply class-conscious but multicultural. I had Muslim, Tamil, and Buddhist friends, and there were many Parsi boys at school, some of whom became my closest companions. Lunches were brought from home, and we often shared our food. However, while Colombo’s middle-class life was diverse, the rural areas were different—some villages were homogeneous, while others were mixed. Sri Lanka’s population was composed of Sinhalese, Tamils, Burghers (mixed Dutch or Portuguese descent), Arabs, Chinese, and even an African community—descendants of slaves brought by the Portuguese. The indigenous people, the Veddahs, were few in number.

Studying in England

My father studied medicine in England, as had his father before him. My grandfather trained in Edinburgh in the late 19th century, and my father attended Cambridge and University College Hospital (UCH), just as I did. I left for England at 17 to study medicine. Before securing my place, I had to pass the first MB examination in London, so I attended a ‘cram school’ where foreign students prepared intensively for British university entrance exams.

Finding accommodation was difficult. Many places displayed signs reading ‘No Coloureds, No Irish’—sometimes even ‘No Dogs,’ though dogs faced less discrimination than people. I briefly stayed in a hostel run by Methodist ex-missionaries from China before moving to Cambridge. There, the experience was different—students were well looked after. When I arrived, a porter carried my suitcase to my room.

Students lived in college housing for their first year but had to find private accommodation afterward. In my case, my tutor allowed me to stay in college because he knew I would struggle to find a place elsewhere. However, in my third year, I stayed in a vicarage because the vicar was willing to take in Black students. While there was no overt hostility, an undercurrent of prejudice remained. Cambridge students were polite to each other but condescending toward townspeople. We wore gowns outside college and looked down on non-students. This was the 1950s.

For clinical studies, I moved to London. Though conditions were improving, I disliked the city. Looking back, Cambridge felt like a bubble. Life was different outside the elite universities. At one hospital round, an Australian instructor asked me a question. When I hesitated, he said, “Of course, you people always sit on the fence”—a reference to the non-aligned movement led by India and Indonesia. The other students laughed. I smiled weakly but cried inside.

I often skipped sessions to avoid such treatment, something I later regretted—especially in anaesthetics. Today, medical education has changed; overt racism has diminished, at least in London and major cities. Yet, psychiatry remains resistant to change. The system still fails to adapt to Britain’s multicultural reality and continues to be structurally racist.

Psychiatry and Advocacy

I qualified as a doctor but soon realized I did not enjoy surgery or general medicine. Had I been given a choice, I would have studied English and become a writer. But with a family legacy of doctors, I had followed expectations. Psychiatry intrigued me, so I pursued it despite the challenges. I returned to Sri Lanka in 1960 for work experience at the Angoda Mental Hospital near Colombo, which was recognized for psychiatric training. The conditions were appalling, but I learned a great deal. A Viennese neuropsychiatrist, who spoke neither Sinhalese nor Tamil, would sit beside his patients, place an arm around them, and speak softly unlike local psychiatrists, his patients improved. That moment reshaped my view on ethnic matching—it is not always necessary.

Back in England, I became more vocal about psychiatric practices, particularly their injustices toward racial minorities. I opposed over-reliance on medication and compulsory hospitalization. I resisted the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), except in life-threatening cases. Later, I stopped using it altogether.

My advocacy work intensified in the 1980s. I hoped for systemic reform, but psychiatry remains entrenched in outdated models, perpetuating racial disparities. One of my most recent projects has been challenging the schizophrenia diagnosis, advocating for a less rigid, more inclusive approach.

Even now, I remain engaged in improving mental health care in Sri Lanka, working alongside British and Canadian colleagues. Reflecting on both countries, I see Britain becoming more tolerant while Sri Lanka, at times, seems to regress.

At 80, I remain tireless in my advocacy. I hope this conversation helps others understand the complexities of mental health and cultural identity. As the evening darkened, we ended our discussion, though Suman Fernando showed no signs of fatigue. It was a privilege to speak with him, and I hope this record allows others to share in this remarkable journey.

Features

Development must mean human development

Neo-liberal economists assess economic development using parameters like GDP growth, inflation rate, interest rates, debt/GDP ratio and such and recommend measures to improve these expecting a resultant improvement in poverty rates, employment and household income, but this seldom happens as revealed by increasing inequality, decline in real incomes, malnutrition and school dropouts. Increased GDP doesn’t always translate into improved living standards or reduced poverty if benefits aren’t shared.

Quality of life has to be measured in terms of health, education, morals, satisfying employment and cultural activity. Further the society and environment of humans must be conducive for achieving a satisfactory quality of life. Present development models designed to fit the global neoliberalism focus on the development of the economy often at the expense of poor lives, labour, environment, morals and culture.

Human Development

Development must mean human development because true progress focuses on expanding people’s freedoms, capabilities (health, education, skills), and choices, rather than just economic growth (GDP). It’s a people-centered process that ensures individuals can lead fulfilling, productive lives, requiring inclusive policies, social equity, environmental stewardship, and empowerment for meaningful participation in society, moving beyond mere income increases to holistic well-being and human potential. True development addresses social, cultural, political, and environmental aspects alongside economic progress for sustainable well-being. Development, at its core, is about the expansion of human potential and rights, ensuring everyone has a chance to achieve their full potential.

It’s a transformative process that prioritizes people, their freedoms, and their ability to shape their own lives, making it a fundamental human right and the true measure of societal progress. Investing in education, healthcare, and culture has a powerful multiplier effect on families and societies

If Sri Lanka is taken as an example, over the 70 years since independence economic, social, health and education disparity between the rich and the poor has increased. Poverty rate at present is 24%, malnutrition is hovering around 15%, school dropout rates are alarmingly high, environment and climate vulnerability as experienced recently is frightening, regarding morals less spoken the better, and debt pressure is uncontrollable despite IMF.

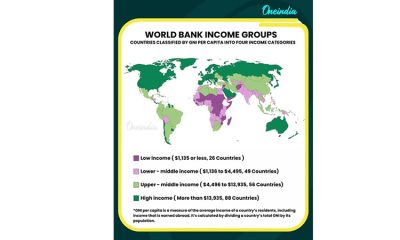

Global Scene

Global scene is no better with inequality rising even in countries like the US, Europe, except in China and Vietnam. Poverty rate in the US is 11% and in Europe 12%. In contrast, China and Vietnam, which are not wholly linked to the neo-liberal economic system, have poverty rates below 1% and 4%, respectively. India still has a substantial number below an income level of USD 3.65 per day amounting to about 40% though extreme poverty (income below USD 2.5 a day) has reduced to about 2%. The upper 10% in the countries with more than 10% poverty own more than 60% of the wealth. One may argue that poverty cannot be totally eliminated, however it needs only 0.3% of the global GDP to eradicate poverty of people living below an income level of USD 2.5 per day. The rich don’t seem to care about this sad situation.

Wealth inequality in Sri Lanka is severe, with recent UNDP reports (2023) placing it among the top five most unequal countries in Asia-Pacific, where the richest 1% own about 31% of wealth, while the poorest 50% own less than 4%; this concentration of assets, coupled with the recent economic crisis, exacerbates deep gaps between rich and poor. Income gaps are stark, with Colombo district seeing the richest group hold over 72% of household income, compared to lower-income areas. Despite easing inflation and reasonable GDP growth, food prices more than doubled between 2021 and 2024, contributing to elevated malnutrition and food insecurity and real wages remain below their 2019 levels.

These facts and figures clearly show that neo-liberal policies have failed in human development in Sri Lanka as well as all countries in the grip of neoliberalism. A quarter of the population is in decline in health, education, real income, employment, morals, culture and all other good aspects of living. On the other hand, in countries which are not bound by the neo-liberal global system poor people are not on the decline but are well incorporated in the inclusive system of governance. Martin Jacques a British journalist and author of When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order, has lauded the Chinese model for its economic success and argued that it represents a distinct, effective approach to governance.

Broad-based investment

Sourabh Gupta, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Institute for China-America Studies, has praised China’s governance model for its “broad-based” investment in people, including healthcare, education, and infrastructure. China’s governance model prioritizes stability and long-term policy continuity, positioning it as an adaptable and effective system in certain non-Western contexts. The model’s emphasis on performance-based governance, continuous public engagement through consultative mechanisms, and controlled media strategies presents a unique approach that aligns well with the developmental needs of some emerging economies (M Y Abesha, B F Kebede, 2024). Similarly praise for the Vietnamese system of government, often centers on its political stability, the success of its Đổi Mới (Renovation) economic reforms, and its ability to maintain rapid, sustained growth.

In the grip of neo-liberalism

It is not that the countries caught in the grip of neo-liberalism have not made special attempts to improve the lot of the poor and it is also true that there had been significant improvements but the gains are not stable, and are very much vulnerable to external vagaries such as Trump and his tariffs, climate disasters, etc. as recently observed in Sri Lanka where poverty jumped from 14% to 24%. This is the fault of the system we are caught in and not so much in the intentions or competence of governments. Having said that, the onus however, is on the rulers to try and develop alternate systems that address poverty and human development.

The greed dependent, consumerism driven, profit motivated neo-liberal systems focus on capital accumulation and expect benefits to trickle down to the poor, but as seen so often the amounts that trickle down are woefully inadequate to solve poverty. This is why the national poverty statistics show that the richest country in the world, the US has 11% poor people while China has almost none. This is despite continuous effort by the US government to solve and overcome the problem.

This predicament is common to all poor countries in the global south, they are all in the neo-liberal trap. Individual countries cannot escape even if they want to. If they attempt it what could happen could be seen when one looks around. Vietnam had to pay a heavy price to defeat two imperial powers and fortunately they had Ho Chi Minh which made all the difference. Iraq, Libya, Syria, Venezuela lost but their people may still harbour anti-imperial fervour and one day may rise up.

Need for new World Order

Instead of waiting for that day what has to be done, as I have repeatedly said in my earlier letters in these columns, is for the global south to join forces and develop a new world order based on an economic system that would emphasize on human development rather than GDP, which would have the capacity to face up to the might of imperialism. Together they would be a force that could fearlessly face up to the hegemony of the global north. The new world order must jettison the export led economic model and instead make self- sufficiency in each country the common goal. Instead of competition between these countries to produce for export to the global north, there should be cooperation to help each other to achieve self-sufficiency and human development. If countries of the global south become self-sufficient in essential needs neo-liberalism will be eradicated and human development would take precedence.

by N. A. de S. Amaratunga

Features

The Separation of Powers and the Independence of the Judiciary

Checks and Balances in the Present Constitution

Moreover, the recent ruling given by the Speaker in Parliament on January 9, 2026, on the Opposition Motion to appoint a Select Committee to review recent appointments made by the JSC to the Judiciary further buttresses the explicit recognition of the SOP and the independence of the Judiciary. The Speaker reiterated the commitment of Parliament to the doctrine of the SOP and refused the Motion on the basis inter alia that Parliament was not hierarchically superior to the Judiciary and cannot be permitted to control the judiciary by creating an oversight mechanism with regard to the JSC.

Professor G.L. Peiris (Prof. GLP) in a speech delivered on December 12, 2025 at the International Research Conference at the Faculty of Law, University of Colombo published in The Island of December 15, 2025 under the caption “Presidential authority in times of emergency – A contemporary appraisal” has critiqued the majority judgment of the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka in Ambika Sathkunanathan V. A.G. on the declaration of emergency by Ranil Wickremesinghe as Acting President on July17, 2022 in response to the Aragalaya. The majority held that Wickremasinghe had violated the Fundamental Rights of the people by a Declaration of a State of Emergency. The author was to attend this event but was unable to do so due to a professional commitment out of Colombo.

After citing authority from several foreign jurisdictions in support of his view of judicial deference to the Executive on matters relating to an Emergency, he advances as one of the grounds as to why the majority were wrong in the Sri Lankan context is that the predisposition to judicial deference is reinforced by a firmly entrenched constitutional norm – “a foundational principle of our public law is the vesting of judicial power not in the courts but in parliament, which exercises judicial power through the instrument of the courts. This is made explicit by Article 4(c) of the constitution which provides “the judicial power of the People shall be exercised by Parliament through courts, tribunals and institutions created and established, or recognised by the Constitution, or created and established by law, except in regard to matters relating to the privileges, immunities and powers of Parliament and of its members, wherein the judicial power of the People may be exercised directly by Parliament according to law” . Prof GLP opines that the majority judgment constitutes “judicial overreach which has many undesirable consequences” including “traducing constitutional traditions; subverting the specific model of separation of powers reflected in our Constitution”.

Prof. GLP, is in effect advancing the view that the Sri Lankan Courts in the present constitutional framework of the Second Republican Constitution 1978 are subservient to the Executive or Parliament.

This view of Prof. GLP is with respect, wrong on both constitutional principle and policy. There are no constitutional restraints on the judicial review of executive action in relation to declarations of emergency. Self-imposed judicial restraint may well constitute an abdication of judicial responsibility.

Unlike the Independence Constitution where a Separation of Powers (SOP) was found by judicial interpretation with the concomitant judicial power to even strike down post enacted legislation, the 1st Republican Constitution of 1972 explicitly did away with the concept of an SOP and instead whilst vesting sovereignty in the people, nevertheless made the National State Assembly the supreme instrument of state power exercising the Executive, Legislative and Judicial power of the people (vide Article 5). Resultantly the judicial review of enacted legislation was expressly done away with and instead pre-enactment review of a Bill tabled in Parliament by a Constitutional Court was provided for.

Indisputably, this fundamental departure introduced by the First Republican Constitution was a direct response to the Queen V. Liyanage and the other judicial power cases where the Courts expressly recognised an SOP and the jurisdiction to even review the constitutionality of post enacted legislation.

But this doctrine of the abolishing of the SOP was subsequently abandoned, and one of the significant and welcome departures introduced by the Second Republican Constitution of 1978 was the explicit reintroduction into our constitutional framework of the principle of an SOP. This is made explicit by Articles 3 and 4 of the Constitution which vests Sovereignty in the people but proceeds to delineate how that sovereignty is exercised in terms of the trichotomy of the Executive, Legislative and Judicial powers and the further recognition of franchise and Fundamental Rights as also integral components of the sovereignty of the people.

Although the twin principles introduced in 1972 of a constitutional bar on the post-enactment review of legislation was retained together with the pre-enactment review of legislation in the present 1978 Constitution, nevertheless the reintroduction of the SOP which guarantees the independence of the Judiciary is a fundamental feature of the present Constitution.

Although Article 4(c) of the present Constitution does state that “the judicial power of the People shall be exercised by Parliament through courts … recognised by the Constitution … except in regard to matters relating to the privileges, immunities and powers of Parliament and of its Members, wherein the judicial power of the People may be exercised directly by Parliament according to law”, nevertheless there is a cursus curiae (practice of the court) of judicial authority by the Sri Lankan superior Courts that have recognised both the concepts of the SOP and the independence of the Judiciary from Executive or Legislative encroachment.

Leading cases which have recognized an SOP include Premachandra V. Monty Jayawickrema (1994) 2 SLR 90 (SC) and the Supreme Court Determination on the 19th Amendment to the Constitution (2002) in which the author appeared as Junior Counsel to the late Deshamanya H.L. de Silva P.C. The Supreme Court has recognised that the independence of the Judiciary is an intrinsic component of the present Constitution in several cases including the Court’s Determination on the Industrial Disputes Act (Special Provisions) Bill 2022. In fact, a more explicit pronouncement was made in Hewamanne V. De Silva where the Supreme Court held that judicial power vested solely and exclusively in the Judiciary (1983) 1 SLR 1 at 20.

Moreover, the explicit vesting in the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka under Articles 125 and 126 of the exclusive jurisdiction to interpret the Constitution and in respect of Fundamental Rights underscores the preeminent role of the Judiciary in our constitutional framework. Foundational principle of the present Constitution as recognized by our Courts include the Rule of Law, power is a trust, and there are no unfettered discretion in public law. Regrettably, Prof. GLP assails these welcome advances made in our public law jurisprudence.

In our constitutional setting of checks and balances and judicial oversight it is the function of the Judiciary to review the legality of Executive action, including matters relating to the declaration of a State of Emergency and Emergency Regulations. The duty of interpreting an Act of Parliament is a function of Courts and not of Parliament (Court of Appeal in C.W.C. V. Superintendent, Beragala Estates 76 NLR 1). The author cited this decision to the Supreme Court in challenging the Inland Revenue Bill introduced by the late Mangala Samaraweera. That Court reiterated this principle and agreeing with the author, ordered a referendum on a particular Clause.

Even in the pre-independence period up to 1948, when vide powers were conferred on the Governor who exercised Executive authority, the Courts have unequivocally reviewed the legality of executive action as manifest by the significant decision of the Supreme Court in 1937 in “In Re. Mark Anthony Lester Bracegirdle“, where the executive act of the Governor of arrest and deportation of Bracegirdle to Australia was reviewed by the Supreme Court and quashed. This decision was a striking assertion of judicial independence and is the first significant judicial review of executive action.

Moreover, the recent ruling given by the Speaker in Parliament on January 9, 2026, on the Opposition Motion to appoint a Select Committee to review recent appointments made by the JSC to the Judiciary further buttresses the explicit recognition of the SOP and the independence of the Judiciary. The Speaker reiterated the commitment of Parliament to the doctrine of the SOP and refused the Motion on the basis inter alia that Parliament was not hierarchically superior to the Judiciary and cannot be permitted to control the judiciary by creating an oversight mechanism with regard to the JSC.

(The author is a President’s Counsel and a Professor of Law)

By Nigel Hatch1

Features

Trump’s Interregnum

Trump is full of surprises; he is both leader and entertainer. Nearly nine hours into a long flight, a journey that had to U-turn over technical issues and embark on a new flight, Trump came straight to the Davos stage and spoke for nearly two hours without a sip of water. What he spoke about in Davos is another issue, but the way he stands and talks is unique in this 79-year-old man who is defining the world for the worse. Now Trump comes up with the Board of Peace, a ticket to membership that demands a one-billion-dollar entrance fee for permanent participation. It works, for how long nobody knows, but as long as Trump is there it might. Look at how many Muslim-majority and wealthy countries accepted: Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, Jordan, Qatar, Pakistan, Indonesia, and the United Arab Emirates are ready to be on board. Around 25–30 countries reportedly have already expressed the willingness to join.

The most interesting question, and one rarely asked by those who speak about Donald J. Trump, is how much he has earned during the first year of his second term. Liberal Democrats, authoritarian socialists, non-aligned misled-path walkers hail and hate him, but few look at the financial outcome of his politics. His wealth has increased by about three billion dollars, largely due to the crypto economy, which is why he pardoned the founder of Binance, the China-born Changpeng Zhao. “To be rich like hell,” is what Trump wanted. To fault line liberal democracy, Trump is the perfect example. What Trump is doing — dismantling the old façade of liberal democracy at the very moment it can no longer survive — is, in a way, a greater contribution to the West. But I still respect the West, because the West still has a handful of genuine scholars who do not dare to look in the mirror and accept the havoc their leaders created in the name of humanity.

Democracy in the Arab world was dismantled by the West. You may be surprised, but that is the fact. Elizabeth Thompson of American University, in her book How the West Stole Democracy from the Arabs, meticulously details how democracy was stolen from the Arabs. “No ruler, no matter how exalted, stood above the will of the nation,” she quotes Arab constitutional writing, adding that “the people are the source of all authority.” These are not the words of European revolutionaries, nor of post-war liberal philosophers; they were spoken, written and enacted in Syria in 1919–1920 by Arab parliamentarians, Islamic reformers and constitutionalists who believed democracy to be a universal right, not a Western possession. Members of the Syrian Arab Congress in Damascus, the elected assembly that drafted a democratic constitution declaring popular sovereignty — were dissolved by French colonial forces. That was the past; now, with the Board of Peace, the old remnants return in a new form.

Trump got one thing very clear among many others: Western liberal ideology is nothing but sophisticated doublespeak dressed in various forms. They go to West Asia, which they named the Middle East, and bomb Arabs; then they go to Myanmar and other places to protect Muslims from Buddhists. They go to Africa to “contribute” to livelihoods, while generations of people were ripped from their homeland, taken as slaves and sold.

How can Gramsci, whose 135th birth anniversary fell this week on 22 January, help us escape the present social-political quagmire? Gramsci was writing in prison under Mussolini’s fascist regime. He produced a body of work that is neither a manifesto nor a programme, but a theory of power that understands domination not only as coercion but as culture, civil society and the way people perceive their world. In the Prison Notebooks he wrote, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old world is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid phenomena appear.” This is not a metaphor. Gramsci was identifying the structural limbo that occurs when foundational certainties collapse but no viable alternative has yet emerged.

The relevance of this insight today cannot be overstated. We are living through overlapping crises: environmental collapse, fragmentation of political consensus, erosion of trust in institutions, the acceleration of automation and algorithmic governance that replaces judgment with calculation, and the rise of leaders who treat geopolitics as purely transactional. Slavoj Žižek, in his column last year, reminded us that the crisis is not temporary. The assumption that history’s forward momentum will automatically yield a better future is a dangerous delusion. Instead, the present is a battlefield where what we thought would be the new may itself contain the seeds of degeneration. Trump’s Board of Peace, with its one-billion-dollar gatekeeping model, embodies this condition: it claims to address global violence yet operates on transactional logic, prioritizing wealth over justice and promising reconstruction without clear mechanisms of accountability or inclusion beyond those with money.

Gramsci’s critique helps us see this for what it is: not a corrective to global disorder, but a reenactment of elite domination under a new mechanism. Gramsci did not believe domination could be maintained by force alone; he argued that in advanced societies power rests on gaining “the consent and the active participation of the great masses,” and that domination is sustained by “the intellectual and moral leadership” that turns the ruling class’s values into common sense. It is not coercion alone that sustains capitalism, but ideological consensus embedded in everyday institutions — family, education, media — that make the existing order appear normal and inevitable. Trump’s Board of Peace plays directly into this mode: styled as a peace-building institution, it gains legitimacy through performance and symbolic endorsement by diverse member states, while the deeper structures of inequality and global power imbalance remain untouched.

Worse, the Board’s structure, with contributions determining permanence, mimics the logic of a marketplace for geopolitical influence. It turns peace into a commodity, something to be purchased rather than fought for through sustained collective action addressing the root causes of conflict. But this is exactly what today’s democracies are doing behind the scenes while preaching rules-based order on the stage. In Gramsci’s terms, this is transformismo — the absorption of dissent into frameworks that neutralize radical content and preserve the status quo under new branding.

If we are to extract a path out of this impasse, we must recognize that the current quagmire is more than political theatre or the result of a flawed leader. It arises from a deeper collapse of hegemonic frameworks that once allowed societies to function with coherence. The old liberal order, with its faith in institutions and incremental reform, has lost its capacity to command loyalty. The new order struggling to be born has not yet articulated a compelling vision that unifies disparate struggles — ecological, economic, racial, cultural — into a coherent project of emancipation rather than fragmentation.

To confront Trump’s phenomenon as a portal — as Žižek suggests, a threshold through which history may either proceed to annihilation or re-emerge in a radically different form — is to grasp Gramsci’s insistence that politics is a struggle for meaning and direction, not merely for offices or policies. A Gramscian approach would not waste energy on denunciation alone; it would engage in building counter-hegemony — alternative institutions, discourses, and practices that lay the groundwork for new popular consent. It would link ecological justice to economic democracy, it would affirm the agency of ordinary people rather than treating them as passive subjects, and it would reject the commodification of peace.

Gramsci’s maxim “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will” captures this attitude precisely: clear-eyed recognition of how deep and persistent the crisis is, coupled with an unflinching commitment to action. In an age where AI and algorithmic governance threaten to redefine humanity’s relation to decision-making, where legitimacy is increasingly measured by currency flows rather than human welfare, Gramsci offers not a simple answer but a framework to understand why the old certainties have crumbled and how the new might still be forged through collective effort. The problem is not the lack of theory or insight; it is the absence of a political subject capable of turning analysis into a sustained force for transformation. Without a new form of organized will, the interregnum will continue, and the world will remain trapped between the decay of the old and the absence of the new.

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa ✍️

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoHistory of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine Kandana

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe middle-class money trap: Why looking rich keeps Sri Lankans poor