Midweek Review

The Kandy-floss Tea-Dance, or Walk like an Elephant

by Laleen Jayamanne

The Lankan ‘Tea-dance’ is a consciously-willed confection of a so-called ‘folk dance,’ attributed to the Malaiyaha women who work on the tea estates. Therefore, it is a frozen form with no basis in a living culture. Here I take ‘Kandy’ as a synonym for the hill-country, ‘Kande udarata,’ and also to describe the aesthetic quality of the artificial Tea-dance as candy, much like Bombai Motai (pink candy-floss woven of sugar and air).

Dr Sudesh Mantillake, the dance scholar and trained Kandyan dancer himself, has stated (in an original research paper) that the Tea-dance was invented in the 70s as part of a move by the state to invent folk dance traditions for the country, in the post-colonial Sinhala nationalist cultural revival, linked to various patterns and gestures associated with rural work. I am grateful to him for having formulated this field of research from a postcolonial theoretical perspective.

So, for the Sinhala girls, the kalagedi dance’ and the ‘harvesting of paddy dance’ were invented. I have photos of myself and friends doing both in primary school, wearing a cloth and choli jacket with small pots on our head. The Tamil girls in our school did Bharathanatyam, and some, irrespective of ethnicity did Manipuri, Ballet, Kandyan and even Spanish dancing at our school run by Irish Catholic nuns. According to Mantillake, distinguished Sinhala dancers and dance educators such as Pani Bharatha (with a resonant Indian name), Sri Jayana and colleagues invented the folk dances including the Tea-dance. It appears that the Tea-dance was made mostly for foreign consumption, without any engagement with the Malaiyaha communities, to popularise Ceylon Tea and also entertain the Lankan diaspora nostalgically celebrating Lankan festivals and National events. There are such shows in LA, Paris and New Zealand (I learn on YouTube), some done even by little girls of about five or six. The dancers are all girls, while usually there is a young boy as a Kangani with a cane in hand, supervising and flirting with them and creating bits of silly comedy. I discovered that the original Tea-dance was in fact British social dancing done by the colonial folk in Asia to liven up afternoon gatherings for tea-sipping and such. So, the name of the colonial masters’ dance was branded on the Malaiyaha community by the Lankan state, to sell tea.

The Tea-dance consists largely of gestures plucked from the act of breaking tender tea leaves, crudely combined with those copied from Indian films. The baskets, some small plastic ones, were tied to their back to make dancing easy, and the colourful costumes were also confected out of the transnational Bollywood film repertoire and dance moves. None of this of course had even a faint ‘ethnographic authenticity’.

The baskets the Malaiyaha women carried to work were not tied to their back (as the song in Sinhala says), but rather, were held with a long band strung across their heads which carry the weight, compressing the spine, as the neck is constantly bent to find the exact tender tea leaf. A Malaiyaha woman would only get a full days’ union award wage if they filled the large baskets with 16 kilos of tea per day!

Now, it’s this container, carrying the weight of their heavy labour, that is flung around like a light pot high in the air just for fun by the Sinhala girls rounded up to dance and prance around on a stage amidst admiring parents and a few whites. They hitch their skirts and provocatively shake and stick their hips out and carry on like some Bollywood dancers, producing pure kitsch. None of this is edifying in terms of gender stereotypes for these youngsters inculcated into ‘Lankan folk traditions.’

Mantillake cites Tamil names of a variety of folk-dance forms practised by the Malaiyaha folk and makes the point that the Tea-dance does not draw material from any of them. And in Sumathy Sivamohan’s feature film of the Malaiyaha, Ingirunthu (2013), there is a Hindu festival at the local Kovil with an extraordinary range of dancing by the devotees, both children and adults, as part of religious festivity. Some of the dancers show how their own folk-dance forms have evolved among them to include transsexual, transmedia dance gestures seen in many other parts of the world, including Indian films. I also noticed one transsexual dancer dressed as such figures did when they popped up from time to time in some early Sinhala films, such Pitisara Kella (Village Lass). Such figures were always found on urban streets, dancing for money, dressed in long twirling skirts. In those days, the name for them was napunsakaya, neither male nor female. This hybrid mixture of moves, gestures and rhythms, internalised and absorbed by the dancers at the festival, was an actual ethnographic event (of the people, by the people and for the people), filmed respectfully by Sivamohan’s camera and clearly of value to the Malaiyaha community gathered at the festival ritual to celebrate their gods.

So, the dancing of the folk at these religious festivals is not a mummified museum category among Hindu communities on the tea estates, but is, rather, open to the transnational flow of contemporary media images as well. It’s this living syncretic tradition of collective dance that sustains them spiritually and emotionally and lifts them up from their daily arduous physical drudgery. For the Hindus, dance is an integral part of the metaphysics of their religion because within its cosmology the world comes into being, and is also dissolved, by the Dance of Shiva Nataraja, the king of dance. However, the three great Middle Eastern Religions of The Book, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, focus on The Word, proscribing the primordial body in dance. And sadly, according to the bible story of Genesis, the human body is fallen, sinful, banished from paradise.

When dance is invented according to the imperatives of state patronage, without some integral local connection to the lives of people whose emotional expression it is, the result is a highly artificial dance, a parody and an insult to the folk it supposedly represents. No other South Asian country would stoop so low as to sell their own, say Darjeeling tea for instance, with such a gimmick.

Fabricated dances

These fabricated dances also run the risk of sanitisation of folk traditions of their own. When this ideology determines the school and university curricula one has a perfect recipe for recreating mediocrity, through inbreeding. Mantillake, as an educator himself, is especially critical of the deleterious effects of such a dance curriculum on schoolchildren, in promulgating ethnic stereotypes of minorities. Lankans could have studied how India revived and nurtured their vast repertoire of traditions during decolonisation under Nehru’s modern cultural policies, from song to dance, from weaving to painting and sculpture. They had lost some of their dance forms but they had the theoretical texts (shasthriya) and the temple sculpture from which scholar-dancers were able to derive the mudras and poses, create anew the Indian traditions and train the young.

This was possible also because Indian classical forms reach towards the principle of the pose of dynamic equilibrium. Just imagine Siva Nataraja poised on one leg, balancing on a tortoise while dancing with his many arms, beating the hour-glass drum. It’s a life-size bronze icon of Shiva Nataraja that the Government of India gifted to CERN, the centre for the study of quantum phenomena such as the Higgs Boson, in Switzerland. Shiva Nataraja now dances there communing with the quantum energy of the universe.

We can move from the classical to the simplest of Indian folk instruments, the bata-nalava, the bamboo flute of both Krishna and the cow-herd, to understand the richness of Indian performance modes. There is an annual folk festival of flutes of a hundred and one varieties, and folk-group dances of both men and women, who dance for days, with startling Dionysian intensity and joy. Kumar Shahani’s film of this festival is on YouTube, called The Bamboo Flute (2000). In the same film he also has Pandith Hariprasad Chaurasia play his classical flute seated on the floor of his middle-class flat in Mumbai. Perhaps, the British didn’t reach the village folk playing the flute and therefore the unbroken evolution of the form, from the folk (Deshiya), to the most sophisticated of classical forms (Margiya), was possible and is perceptible and audible to this day. This was one of Ananda Coomaraswamy’s key ideas based on his meticulous research.

Perhaps, in the first instance, the dance forms of the folk were very few in Sinhala Buddhist villages (except in rituals of exorcism), regulated by the ethos of the Temple based on the precepts of Theravadha Buddhism, with its emphasis on calming the body and mind in meditation and chanting. Is this why many Buddhists are drawn to Katharagama (a Hindu shrine devoted to the brother of Ganesh, Skanda), and the trance dancing there?). Is this also why Asoka Handagama had an extended sequence of older Dalith men and women dancing together seriously, self-forgetfully, in a secular open air space, after work, on their pay-day, in his film Alborada (2021)? I hesitate though to call it an orientalising moment in the Sinhala cinema because the dancing was given a certain respectful attention. The director’s and Neruda’s fascination with the dancing is quite mutual and rather appealing.

Whatever the case, what appears to happen in the ‘nationalised folk-dance forms’ is that girls especially have become, in my opinion, more and more narcissistic as performers, incited to be ‘sexy’, elaborating a very limited set of gestures and movements, some of which are directly inflected by provocative Indian film dance moves, pure fluff. The Popular Indian film music and dance were originally derived from the four or five classical forms, according to Paul Willemen, who co-wrote the 2-volume Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema. His argument was that the film music and songs created a new 5th form initially, a hybrid, very outward looking one, aware also of Hollywood musicals from the 1940s. They were performed by highly trained professionals. Now, after globalisation and the internet and social media, the speedy hybridisation cannot any longer be quantified, and doesn’t even need to be for purposes of legitimisation of that once critically maligned popular cinema, because of its transnational reach, domestic social and political power.

Dance Therapy

A Kuchupudi dance teacher in Sydney decided to go back to Kerala, where she was from, and opened a dance studio which I visited once. She was about to start a workshop for a small group of young girls and told me that she was doing dance movements based on different kinds of walking rhythms. She told me to sit and observe but that I could also join in if I felt like it. My friend’s formal training was in Odissi, a classical form but she was dissatisfied with formal rigour and wanted to work as a dance therapist in a looser way, exploring movements, and had thought the many forms of walking in Indian dance would be good to start with.

Some of these are: walking like an elephant, walking like a deer, walking like a floating swan, walking on lotus flowers etc. I had previously seen these in Kumar Shahani’s films on dance, The Bamboo Flute (2000), and Bhavantaran (Immanence, 1991), a tribute to Guru Kelucharan Mahapathra, exponent of Odissi. At the opening of The Bamboo Flute, Alarmel Valli danced a magnificent invocation to Ganapathi (Ganesh), in the open air, near a temple beside a lake. There, this slim dancer also walked, swaying majestically like an elephant, with flute music in the air.

My friend’s workshop on walking was for young girls who were feeling low, withdrawn and depressed. She was interested in rhythmic walking to the beat of drums as a way of activating their feel for walking as such and generate a little energy in their body. She told me that many middle-class Indian mothers now instructed their daughters not to walk with swinging arms, but to keep them still, held beside the body as they walked. That was a code, she said, for restraining the female body of the young girls from using their pelvis in walking, the ‘pelvic walk’ being one associated with sex workers on the streets.

Triviality of Tea dance

When thinking of the triviality of the Tea-dance, these thoughts about dance therapy kept coming to me and I remembered that I found myself joining the girls, walking to the rhythms of the drums and then I found myself crying uncontrollably while still walking to the irresistible drum beats. I remembered that I was neither depressed nor unhappy then and discussed what happened to me with my friend after the class, over a cup of tea. She said that certain drum beats play directly on the nervous system and can touch one deeply, that they are primal vibrations. In Hindu metaphysics, in the beginning was sound. Whereas, according to the Bible, in the beginning was the word.

Trained Indian dancers and ordinary folk across the ages, in villages, towns and cities, have developed dance forms and rhythms, for many occasions and innumerable festivals, with immense intuition and craft skill, which connect deeply with other life worlds. All human communities are known to have danced from the beginning of time. According to anthropologists, two of the most ancient forms of dance are of people moving rhythmically in unison in undulating serpentine lines which become circular. Instead of training young girls to seduce an audience from the early age of six and boys to control them with a stick, even in jest, as in the mindless Sinhala Tea-dance, the Lankan Sinhala Buddhist cultural elite could be a little more mindful in trying to sell Ceylon tea. However, there is now a polished-up version of the Tea-dance (on YouTube, without the kangani), advertised as entertainment for local corporate events, by “Students of State Cultural Centers, Presented by the Ministry of Buddhasasana, Religious and Cultural Affairs.” (To be continued)

Michelle Jayasinghe in her book A Study of the Evolution of Lord Ganesh in Sri Lankan Culture, says that the Hindu Theru Festival was practiced all over Lanka but that the one in Matale at the Arulmigu Shri Muttumariyamman Kovil was special, in that Buddhists also actively participated in it with the Hindu devotees. She adds that it is commonly known that Muslims and Christians also contribute to and participate in it. She also indicates that this festival is of vital importance to the Malaiyaha people of the tea estates, especially given that they have lived and worked in the hill country for nearly two centuries.

“The land was originally part of a paddy field and was gifted by the owner in 1852. The current temple was built in 1874 funded by many devotees. The temple was originally a small statue under a tree prayed by the Hindu people and has been developed by the people in Matale” (The Sunday Observer, 25 February, 2018).

The thought I get from having read Jayasinghe’s cultural study is that there is a rather urgent need to undertake anthropologically based ethnographic field-research, so as to understand how folk from different ethno-religious groups have come together to celebrate five Hindu gods (Shiva, Mahadevi, Ganesh, Skanda, Chandeshvara), by building elaborately decorated chariots for each of them to be paraded through the city, as the major highlight of this festival. Here, the future researchers could also focus on whether the Malaiyaha folk have a unique relationship to this festival, as suggested by Jayasinghe, and if and how the different genders respond to it in their active participation in therapeutic dancing as well.

There is a YouTube film of the Theru festival in Matale where a young woman moves and shakes vigorously in a trance state, while an older man and a woman attend to her with care. This is clearly a therapeutic folk practice (dance) focusing on one single individual, which can’t be commodified. The Kovil itself was also ‘severely damaged’ in the 83 anti-Tamil pogrom. With such a complex history (where ethnicity, politics and religion are enmeshed in desire), the collective festive acts of healing perceptible in the Theru festival in Matale, makes it an iconic multi-ethnic event.

The unusual coexistence of feelings, sensations and emotions, of relaxation and extreme intensity (hanging on hooks, firewalking, trance states), and a continuum of moods between them helps one to observe (on YouTube again) how cultural syncretism comes into life when people mingle in an open way in a fully embodied, mindful, intimate and respectful manner, as in the Matale Theru festive milieu and atmosphere charged with incense, and song.

As Pandith Amaradeva once said, Lanka didn’t have melodic instruments to produce songs (melodies) until they were imported from India. Similarly, in the case of dance, we didn’t have a courtly or a temple tradition to generate classical dance idioms as in the case of Hindu Devadasi and the Persianised Islamic traditions of Moghul India. What we did have were the powerful therapeutic modes, the Kohomba Kankariya ritual, the 18 Sanniyas and daemon masks and the chanting, kavi and drumming. We also didn’t have a martial arts tradition as in Kerala, which contemporary Indian female choreographers have been drawing from in creating modern dance moves, empowering girls and women in India to learn to walk proudly, and defend themselves and enjoy it all as elephants do.

As I was concluding this I saw (on my friend Priyantha Fonseka’s Facebook) some of his clips of the recent Mihindu parade in Kandy celebrating the arrival of Buddhism in Lanka. He also wrote an entry describing the difference between the one he just saw with his children (going past his house) and the ones he remembered from his own childhood. He said, in the past the small perahara started from the temple school where children did kalagedi and lee-keli dances to the sound of drums. The centre piece was a float with statues of Mihindu Thero (son of Asoka), and Thisse as a boy poised to shoot a deer. Such is the parabolic scene of the introduction of avihimsa (non-violence) at the heart of the enlightening religion of Buddhism, to Lanka.

While this same float was there in the contemporary parade, Tisse was played by a real child. But marking a radical change, now there were transvestite and perhaps also transexual drummers and men in sarong and bandanas, drumming bright yellow metallic drums, setting the pace for an irresistible rhythmic walk. The last group were Kavadi dancers, both men and women, clad in red accompanied by a small orchestra of instruments including drums, cymbals, a small horn and even a saxophone (once an instrument prohibited on Radio Ceylon!). The women in bright red saris were balancing very high floral head dresses with ease as they danced. Priyantha concluded with a delightful anecdote. He said that two female spectators nearby began to move restlessly, one seated on her chair having let down her hair and other (having being invited), shooting right into the parade itself, dancing.

As a scholar of theatre, at Peradeniya University, interested in ‘audience participation,’ Priyantha observed that these two women were in their own way undoing the various defence mechanisms and taboos they (the Sinhala folk with their exclusivist ethno-religious identity) had created for themselves, to exclude ‘ethnic others’. It appears then that some of the finest manifestations, actions, of the Aragalaya have sent fresh shoots through the Lankan body politic as a cosmos-polis. Also, perhaps, the folk in Kandy, no doubt long familiar with the Matale Theru festival ethos, were well rehearsed emotionally to make such moves.

Features

Remembering Ernest MacIntyre’s Contribution to Modern Lankan Theatre & Drama

Humour and the Creation of Community:

“As melancholy is sadness that has taken on lightness,

so humour is comedy that has lost its bodily weight”. Italo Calvino on ‘Lightness’ (Six Memos for the New Millennium (Harvard UP, 1988).

With the death of Ernest Thalayasingham MacIntyre or Mac, as he was affectionately known to us, an entire theatrical milieu and the folk who created and nourished Modern Lankan Theatre appear to have almost passed away. I have drawn from Shelagh Goonewardene’s excellent and moving book, This Total Art: Perceptions of Sri Lankan Theatre (Lantana Publishing; Victoria, Australia, 1994), to write this. Also, the rare B&W photographs in it capture the intensity of distant theatrical moments of a long-ago and far-away Ceylon’s multi-ethnic theatrical experiments. But I don’t know if there is a scholarly history, drawing on oral history, critical reviews, of this seminal era (50s and 60s) written by Lankan or other theatre scholars in any of our languages. It is worth remembering that Shelagh was a Burgher who edited her Lankan journalistic reviews and criticism to form part of this book, with new essays on the contribution of Mac to Lankan theatre, written while living here in Australia. It is a labour of love for the country of her birth.

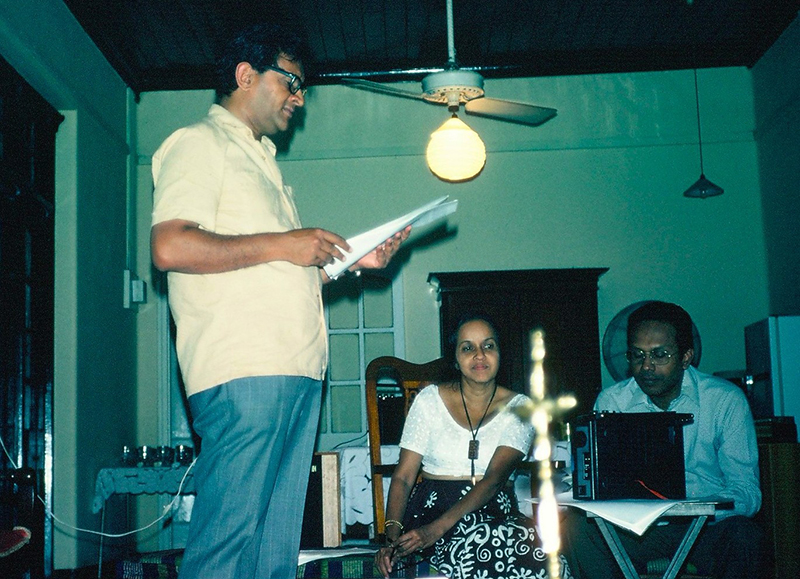

Here I wish to try and remember, now in my old age, what Mac, with his friends and colleagues from the University of Ceylon Drama Society did to create the theatre group called Stage & Set as an ‘infrastructure of the sensible’, so to speak, for theatrical activity in English, centred around the Lionel Wendt Theatre in Colombo 7 in the 60s. And remarkably, how this group connected with the robust Sinhala drama at the Lumbini Theatre in Colombo 5.

Shelagh shows us how Bertolt Brecht’s plays facilitated the opening up of a two-way street between the Sinhala and English language theatre during the mid-sixties, and in this story, Mac played a decisive role. I will take this story up below.

I was an undergraduate student in the mid-sixties who avidly followed theatre in Sinhala and English and the critical writings and radio programmes on it by eminent critics such as Regi Siriwardena and A. J. Gunawardana. I was also an inaugural student at the Aquinas University’s Theatre Workshop directed by Mac in late 1968, I think it was. So, he was my teacher for a brief period when he taught us aspects of staging (composition of space, including design of lighting) and theatre history, and styles of acting. Later in Australia, through my husband Brian Rutnam I became friends with Mac’s family including his young son Amrit and daughter Raina and followed the productions of his own plays here in Sydney, and lately his highly fecund last years when he wrote (while in a nursing home with his wife and comrade in theatre, Nalini Mather, the vice-principal of Ladies’ College) his memoir, A Bend in the River, on their University days. In my review in The Island titled ‘Light Sorrow -Peradeniya Imagination’ I attempted to show how Mac created something like an archaeology of the genesis of the pivotal plays Maname and Sinhabahu by Ediriweera Sarachchandra in 1956 at the University with his students. Mac pithily expressed the terms within which such a national cultural renaissance was enabled in Sinhala; it was made possible, he said, precisely because it was not ‘Sinhala Only’! The ‘it’ here refers to the deep theatrical research Sarachchandra undertook in his travels as well as in writing his book on Lankan folk drama, all of which was made possible because of his excellent knowledge of English.

The 1956 ‘Sinhala Only’ Act of parliament which abolished the status of Tamil as one of the National languages of Ceylon and also English as the language of governance, violated the fundamental rights of the Tamil people of Lanka and is judged as a violent act which has ricocheted across the bloodied history of Lanka ever since.

Mac was born in Colombo to a Tamil father and a Burgher mother and educated at St Patrick’s College in Jaffna after his father died young. While he wrote all his plays in English, he did speak Tamil and Sinhala with a similar level of fluency and took his Brecht productions to Jaffna. I remember seeing his production of Mother Courage and Her Children in 1969 at the Engineering Faculty Theatre at Peradeniya University with the West Indian actress Marjorie Lamont in the lead role.

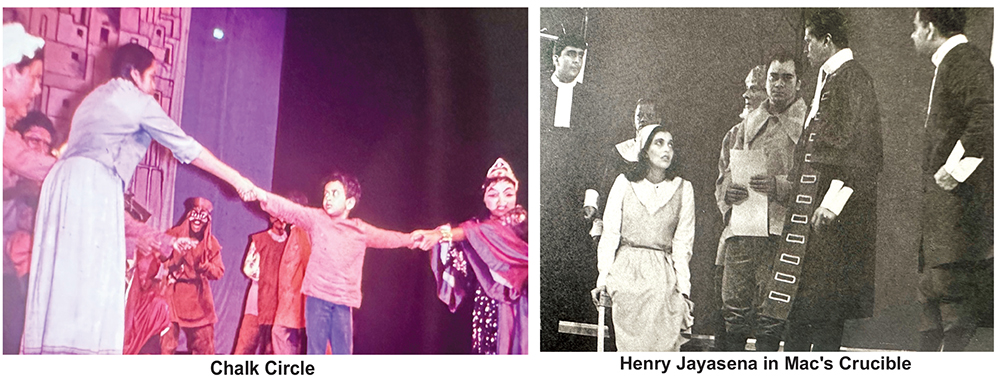

Stage & Set and Brecht in Lanka

The very first production of a Brecht play in Lanka was by Professor E.F. C. Ludowyk (Professor of English at Peradeniya University from 1933 to 1956) who developed the Drama Society that pre-existed his time at the University College by expanding the play-reading group into a group of actors. This fascinating history is available through the letter sent in 1970 to Shelagh by Professor Ludowyk late in his retirement in England. In this letter he says that he produced Brecht’s The Good Woman of Szechwan with the Dram Soc in 1949. Shelagh who was directed by Professor Ludowyk also informs us elsewhere that he had sent from England a copy of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle to Irangani (Meedeniya/Serasinghe) in 1966 and that she in turn had handed it over to Mac, who then produced it in a celebrated production with her in the role of Grusha, which is what opened up the two way-street between the English language theatre of the Wendt and the Lumbini Theatre in Sinhala. Henry Jayasena in turn translated the play into Sinhala, making it one of the most beloved Sinhala plays. Mac performed in Henry’s production as the naughty priest who has the memorable line which he was fond of reciting for us in Sinhala; ‘Dearly beloved wedding and funeral guests, how varied is the fate of man…’. The idiomatic verve of Henry’s translation was such that people now consider the Caucasian Chalk Circle a Sinhala play and is also a text for high school children, I hear. Even a venal president recently quoted a famous line of the selfless Grusha in parliament assuming urbanely that folk knew the reference.

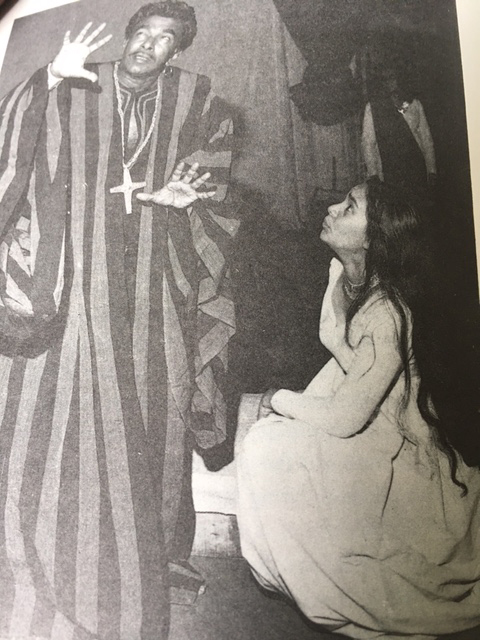

Others will discuss in some detail the classical and modern repertoire of Western plays that Mac directed for Stage & Set and the 27 plays he wrote himself, some of which are published, so that here I just want to suggest the sense of excitement a Stage & Set production would create through the media. I recall how characters in Mac’s production of Othello wore costumes made of Barbara Sansoni’s handloom material crafted specially for it and also the two sets of lead players, Irangani and Winston Serasinghe and Shelagh and Chitrasena. While Serasinghe’s dramatic voice was beautifully textured, Chitrasena with his dancer’s elan brought a kinetic dynamism not seen in a dramatic role, draped in the vibrant cloaks made of the famous heavy handloom cotton, with daring vertical black stripes – there was electricity in the air. Karan Breckenridge as the Story Teller in the Chalk Circle and also as Hamlet, Alastair Rosemale-Cocq as Iago were especially remarkable actors within the ensemble casts of Stage & Set. When Irangani and Winston Serasinghe, (an older and more experienced generation of actors than the nucleus of Stage & Set), joined the group they brought a gravitas and a sense of deep tradition into the group as Irangani was a trained actor with a wonderful deep modulated voice rare on our stage. The photographs of the production are enchanting, luminous moments of Lankan theatre. I had a brief glimpse of the much loved Arts Centre Club (watering hole), where all these people galvanised by theatre, – architects, directors, photographers, artists, actors, musicians, journalists, academics, even the odd senator – all met and mingled and drank and talked regularly, played the piano on a whim, well into the night; a place where many ideas would have been hatched.

A Beckett-ian Couple: Mac & Nalini

In their last few years due to restricted physical mobility (not unlike personae in Samuel Beckett’s last plays), cared for very well at a nursing home, Mac and Nalini were comfortably settled in two large armchairs daily, with their life-long travelling-companion- books piled up around them on two shelves ready to help. With their computers at hand, with Nalini as research assistant with excellent Latin, their mobile, fertile minds roamed the world.

It is this mise-en-scene of their last years that made me see Mac metamorphose into something of a late Beckett dramatis persona, but with a cheeky humour and a voracious appetite for creating scenarios, dramatic ones, bringing unlikely historical figures into conversation with each other (Galileo and Aryabhatta for example). The conversations, rather more ludic and schizoid and yet tinged with reason, sweet reason. Mac’s scenarios were imbued with Absurdist humour and word play so dear to Lankan theatre of a certain era. Lankans loved Waiting for Godot and its Sinhala version, Godot Enakan. Mac loved to laugh till the end and made us laugh as well, and though he was touched by sorrow he made it light with humour.

And I feel that his Memoir was also a love letter to his beloved Nalini and a tribute to her orderly, powerful analytical mind honed through her Classics Honours Degree at Peradeniya University of the 50s. Mac’s mind however, his theatrical imagination, was wild, ‘unruly’ in the sense of not following the rules of the ‘Well-Made play’, and in his own plays he roamed where angels fear to tread. Now in 2026 with the Sinhala translation by Professor Chitra Jayathilaka of his 1990 play Rasanayagam’s Last Riot, audiences will have the chance to experience these remarkable qualities in Sinhala as well.

Impossible Conversations

In the nursing home, he was loved by the staff as he made them laugh and spoke to one of the charge nurses, a Lankan, in Sinhala. Seated there in his room he wrote a series of short well-crafted one-act plays bristling with ideas and strange encounters between figures from world history who were not contemporaries; (Bertolt Brecht and Pope John Paul II, and Galileo Galilei and a humble Lankan Catholic nun at the Vatican), and also of minor figures like poor Yorik, the court jester whom he resurrects to encounter the melancholic prince of Denmark, Hamlet.

Community of Laughter: The Kolam Maduwa of Sydney

A long life-time engaged in theatre as a vital necessity, rather than a professional job, has gifted Mac with a way of perceiving history, especially Lankan history, its blood-soaked post-Independence history and the history of theatre and life itself as a theatre of encounters; ‘all the world’s a stage…’. But all the players were never ‘mere players’ for him, and this was most evident in the way Mac galvanised the Lankan diasporic community of all ethnicities in Sydney into dramatic activity through his group aptly named the Kolam Maduwa, riffing on the multiple meanings of the word Kolam, both a lusty and bawdy dramatic folk form of Lanka and also a lively vernacular term of abuse with multiple shades of meaning, unruly behaviour, in Sinhala.

The intergenerational and international transmission of Brecht’s theatrical experiments and the nurturing of what Eugenio Barba enigmatically calls ‘the secret art of the performer’, given Mac’s own spin, is part of his legacy. Mac gave a chance for anyone who wanted to act, to act in his plays, especially in his Kolam Maduwa performances. He roped in his entire family including his two grand-children, Ayesha and Michael. What mattered to him was not how well someone acted but rather to give a person a chance to shine, even for an instance and the collective excitement, laughter and even anguish one might feel watching in a group, a play such as Antigone or Rasanayagam’s Last Riot.

A colleague of mine gave a course in Theatre Studies at The University of California at Berkeley on ‘A History of Bad Acting’ and I learnt that that was his most popular course! Go figure!

Mac never joined the legendary Dram Soc except in a silent walk-on role in Ludowyk’s final production before he left Ceylon for good. In this he is like Gananath Obeyesekere the Lankan Anthropologist who did foundational and brilliant work on folk rituals of Lanka as Dionysian acts of possession. While Gananath did do English with Ludowyk, he didn’t join the Dram Soc and instead went travelling the country recording folk songs and watching ritual dramas. Mac, I believe, did not study English Lit and instead studied Economics but at the end of A Bend in the River when he and his mates leave the hall of residence what he leaves behind is his Economics text book but instead, carries with him a copy of the Complete Works of Shakespeare.

I imagine that there was a ‘silent transmission of the secret’ as Mac stood silently on that stage in Shaw’s Androcles and the Lion; the compassionate lion. Mac understood why Ludowyk chose that play to be performed in 1956 as his final farewell to the country he loved dearly. Mac knew (among others), this gentle and excellent Lankan scholar’s book The Foot Print of the Buddha written in England in 1958.

Both Gananath and Mac have an innate sense of theatre and with Mac it’s all self-taught, intuitive. He was an auto-didact of immense mental energy. In his last years Mac has conjured up fantastic theatrical scenarios for his own delight, untrammelled by any spatio-temporal constraints. And so it happens that he gives Shakespeare, as he leaves London, one last look at his beloved Globe theatre burnt down to ashes, where ‘all that is solid melts into air’.

However, I wish to conclude on a lighter note touched by the intriguing epigram by Calvino which frames this piece. It is curious that as a director Mac was drawn to Shakespearean tragedy (Hamlet, Othello), rather than comedy. And it becomes even curiouser because as a playwright-director his own preferred genre was comedy and even grotesque-comedy and his only play in the tragic genre is perhaps Irangani. Though the word ‘Riot’ in Rasanayagam’s Last Riot refers to the series of Sinhala pogroms against Tamils, it does have a vernacular meaning, say in theatre, when one says favourably of a performance, ‘it was a riot!’, lively, and there are such scenes even in that play. So then let me end with Calvino quoting from Shakespeare’s deliciously profound comedy As You Like It, framed by his subtle observations.

‘Melancholy and humour, inextricably intermingled, characterize the accents of the Prince of Denmark, accents we have learned to recognise in nearly all Shakespeare’s plays on the lips of so many avatars of Hamlet. One of these, Jacques in As You Like It (IV.1.15-18), defines melancholy in these terms:

“But it is a melancholy of mine own, compounded of many simples, extracted from many objects, and indeed the sundry contemplation of my travels, in which my often rumination wraps me in a most humorous sadness.”’

Calvino’s commentary on Jacques’ self-perception is peerless:

‘It is therefore not a dense, opaque melancholy, but a veil of minute particles of humours and sensations, a fine dust of atoms, like everything else that goes to make up the ultimate substance of the multiplicity of things.’

Ernest Thalayasingham MacIntyre certainly was attuned to and fascinated to the end by the ‘fine dust of atoms, by the veil of minute particles of humours and sensations,’ but one must also add to this, laughter.

by Laleen Jayamanne ✍️

Features

Lake-Side Gems

With a quiet, watchful eye,

The winged natives of the sedate lake,

Have regained their lives of joyful rest,

Following a storm’s battering ram thrust,

Singing that life must go on, come what may,

And gently nudging that picking up the pieces,

Must be carried out with the undying zest,

Of the immortal master-builder architect.

By Lynn Ockersz ✍️

Features

IPKF whitewashed in BJP strategy

A day after the UN freshly repeated the allegation this week that sexual violence had been “part of a deliberate, widespread, and systemic pattern of violations” by the Sri Lankan military and “may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity,” India praised its military (IPKF) for the operations conducted in Sri Lanka during the 1987-1990 period.

Soon after, as if in an echo, Human Rights Watch (HRW) in a statement, dated January 15, 2026, issued from Geneva, quoted Meenakshi Ganguly, Deputy Asia Director at the organisation, as having said: “While the appalling rape and murder of Tamil women by Sri Lankan soldiers at the war’s end has long been known, the UN report shows that systematic sexual abuse was ignored, concealed, and even justified by Sri Lankan government’s unwillingness to punish those responsible.”

Ganguly, who had been with the Western-funded HRW since 2004 went on to say: “Sri Lanka’s international partners need to step up their efforts to promote accountability for war crimes in Sri Lanka.”

To point its finger at Sri Lanka, or for that matter any other weak country, HRW is not that squeaky clean to begin with. In 2012, Human Rights Watch (HRW) accepted a $470,000 donation from Saudi billionaire Mohamed Bin Issa Al Jaber with a condition that the funds are not be used for its work on LGBT rights in the Middle East and North Africa. The donation was kept largely internal until it was revealed by an internal leak published in 2020 by The Intercept. Its Executive Director Kenneth Roth got exposed for taking the kickback. It refunded the money to Al Jaber only after the sordid act was exposed.

The UN, too, is no angel either, as it continues to play deaf, dumb and blind at an intrepid pace to the continuing unprecedented genocide against Palestinians and other atrocities being committed in West Asia and other parts of the world by Western powers.

The HRW statement was headlined ‘Sri Lanka: ‘UN Finds Systemic Sexual Violence During Civil War’, with a strap line ‘Impunity Prevails for Abuses Against Women, Men; Survivors Suffer for Years’

HRW reponds

The HRW didn’t make any reference to the atrocities perpetrated during the Indian Army deployment here.

The Island sought Ganguly’s response to the following queries:

* Would you please provide the number of allegations relating to the period from July 1987 to March 1990 when the Indian Army had been responsible for the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka and the Sri Lanka military confined to their camps, in terms of the Indo-Lanka accord.

* Have you urged the government of India to take tangible measures against the Indian Army personnel for violations perpetrated in Sri Lanka?

* Would you be able to provide the number of complaints received from foreign citizens of Sri Lankan origin?

Meenakshi responded: Thanks so much for reaching out. Hope you have been well? We can’t speak about UN methodology. Please could you reach out to OHCHR. I am happy to respond regarding HRW policies, of course. We hope that Sri Lankan authorities will take the UN findings on conflict-related sexual violence very seriously, regardless of perpetrator, provide appropriate support to survivors, and ensure accountability.

Mantri on IPKF

The Indian statement, issued on January 14, 2026, on the role played by its Army in Sri Lanka, is of significant importance at a time a section of the international community is stepping up pressure on the war-winning country on the ‘human rights’ front.

Addressing about 2,500 veterans at Manekshaw Centre, New Delhi, Indian Defence Minister Raksha Mantri referred to the Indian Army deployment here whereas no specific reference was made to any other conflicts/wars where the Indian military fought. India lost about 1,300 officers and men here. At the peak of Indian deployment here, the mission comprised as many as 100,000 military personnel.

According to the national portal of India, Raksha Mantri remembered the brave ex-servicemen who were part of Operation Pawan launched in Sri Lanka for peacekeeping purposes as part of the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF) almost 40 years ago. Mantri’s statement verbatim: “During the operation, the Indian forces displayed extraordinary courage. Many soldiers laid down their lives. Their valour, sacrifices and struggles did not receive the respect they deserved. Today, under the leadership of PM Modi, our government is not only openly acknowledging the contributions of the peacekeeping soldiers who participated in Operation Pawan, but is also in the process of recognising their contributions at every level. When PM Modi visited Sri Lanka in 2015, he paid his respects to the Indian soldiers at the IPKF Memorial. Now, we are also recognising the contributions of the IPKF soldiers at the National War Memorial in New Delhi and giving them the respect they deserv.e” (https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=2214529®=3&lang=2)

One-time President of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and ex-Home Minister Mantri received the Defence Portfolio in 2019. There hadn’t been a similar statement from any Modi appointed Defence Minister since he became the Prime Minister in 2014.

Perhaps, we should remind Mantri that Operation Pawan hadn’t been launched for peacekeeping purposes and the Indian Army deployment here cannot be discussed without examining the treacherous Indian destabilisation project launched in the early ’80s.

Nothing can be further from the truth than the attempt to describe Operation Pawan as a peacekeeping mission. India destabilised and terrorised Sri Lanka to its heart’s content that the then President JRJ had no option but to accept the so-called Indo-Lanka accord and the deployment of the Indian Army here to supervise the disarming of terrorist groups sponsored by India. Once the planned disarming of terrorist groups went awry in August, 1987 and the LTTE engineered a mass suicide of a group of terrorists who had been held at Palaly airbase, thereby Indian peacekeeping mission was transformed to a military campaign.

Mantri, in his statement, referred to the Indian Army memorial at Battaramulla put up by Sri Lanka years ago. The Indian Defence Minister seems to be unaware of the first monument installed here at Palaly in memory of 33 Indian commandos of the 10 Indian Para Commando unit, including Lieutenant Colonel Arun Kumar Chhabra who died in a miscalculated raid on the Jaffna University at the commencement of Operation Pawan.

BJP politics

Against the backdrop of Mantri’s declaration that India recognised the IPKF at the National War Memorial in New Delhi, it would be pertinent to ask when that decision was taken. The BJP must have decided to accommodate the IPKF at the National War Memorial in New Delhi recently. Otherwise Mantri’s announcement would have been made earlier. Obviously, Modi, the longest serving non-Congress Prime Minister of India, didn’t feel the need to take up the issue vigorously during his first two terms. Modi won three consecutive terms in 2014, 2019 and 2024. Congress great Jawaharlal Nehru is the only other to win three consecutive parliamentary elections in 1951, 1957 and 1962.

The issue at hand is why India failed to recognise the IPKF at the National War Memorial for so long. The first National War Memorial had been built and inaugurated in January 1972 following the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971, but under Modi’s direction India set up a new memorial, spread over 40 acres of land near India Gate Circle. Modi completed the National War Memorial project during his first term.

No one would find fault with India for honouring those who paid the supreme sacrifice in Sri Lanka, but the fact that the deployment of the IPKF took place here under the overall destabilisation project cannot be forgotten. India cannot, under any circumstances, absolve itself of the responsibility for the death and destruction caused as a result of the decision taken by Indira Gandhi, in her capacity as the Prime Minister, to intervene in Sri Lanka. Her son Rajiv Gandhi, in his capacity as the Prime Minister, dispatched the IPKF here after Indian,trained terrorists terrorised the country. India exercised terrorism as an integral part of their overall strategy to compel Sri Lanka to accept the deployment of Indian forces here under the threat of forcible occupation of the Northern and Eastern provinces.

India could have avoided the ill-fated IPKF mission if Premier Rajiv Gandhi allowed the Sri Lankan military to finish off the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in 1987. Unfortunately, India carried out a forced air-drop over the Jaffna peninsula in June, 1987 to compel Sri Lanka to halt ‘Operation Liberation,’ at that time the largest ever ground offensive undertaken against the LTTE. Under Indian threat, Sri Lanka amended its Constitution by enacting the 13th Amendment that temporarily merged the Eastern Province with the Northern Province. That had been the long-standing demand of those who propagated separatist sentiments, both in and outside Parliament here. Don’t forget that the merger of the two provinces had been a longstanding demand and that the Indian Army was here to install an administration loyal to India in the amalgamated administrative unit.

The Indian intervention here gave the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) with an approving wink from Washington as India was then firmly in the Soviet orbit, an opportunity for an all-out insurgency burning anything and everything Indian in the South, including ‘Bombay onions’ as a challenge to the installation of the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation front (EPRLF)-led administration in the North-East province in November 1988. How the Indian Army installed ex-terrorist Varatharaja Perumal’s administration and the formation of the so-called Tamil National Army (TNA) during the period leading to its withdrawal made the Indian military part of the despicable Sri Lanka destabilisation project.

The composition of the first NE provincial council underscored the nature of the despicable Indian operation here. The EPRLF secured 41 seats, the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) 17 seats, Eelam National Democratic Liberation Front (ENDLF) 12 and the United National Party (UNP) 1 in the 71-member council.

The Indian intelligence ran the show here. The ENDLF had been an appendage of the Indian intelligence and served their interests. The ENDLF that had been formed in Chennai (then Madras) by bringing in those who deserted EPRLF, PLOTE (People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam) and Three Stars, a PLOTE splinter group led by Paranthan Rajan was accused of committing atrocities. Even Douglas Devananda, whose recent arrest over his failure to explain the disappearance of a weapon provided to him by the Sri Lanka Army, captured media attention, too, served the ENDLF for a short period. The ENDLF also contested the parliamentary polls conducted under Indian Army supervision in February 1989.

The ENDLF, too, pulled out of Sri Lanka along with the IPKF in 1990, knowing their fate at the hands of the Tigers, then honeymooning with Premadasa.

Dixit on Indira move

The late J.N. Dixit who was accused of behaving like a Viceroy when he served as India’s High Commissioner here (1985 to 1989) in his memoirs ‘Makers of India’s Foreign Policy: Raja Ram Mohun Roy to Yashwant Sinha’ was honest enough to explain the launch of Sri Lanka terrorism here.

In the chapter that also dealt with Sri Lanka, Dixit disclosed the hitherto not discussed truth. According to Dixit, the decision to militarily intervene had been taken by the late Indira Gandhi who spearheaded Indian foreign policy for a period of 15 years – from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 to 1984 (Indira was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards in that year). That disastrous decision that caused so much death and destruction here and the assassination of her son Rajiv Gandhi had been taken during her second tenure (1980 to 1984) as the Prime Minister.

The BJB now seeking to exploit Indira Gandhi’s ill-fated decision probably taken at the onset of her second tenure as the Premier, came into being in 1980. Having described Gandhi’s decision to intervene in Sri Lanka as the most important development in India’s regional equations, one-time Foreign Secretary (December 1991 to January 1994) and National Security Advisor (May 2004 to January 2005) declared that Indian action was unavoidable.

Dixit didn’t mince his words when he mentioned the two major reasons for Indian intervention here namely (1) Sri Lanka’s oppressive and discriminating policies against Tamils and (2) developing security relationship with the US, Pakistan and Israel. Dixit, of course, didn’t acknowledge that there was absolutely no need for Sri Lanka to transform its largely ceremonial military to a lethal fighting force if not for the Indian destabilisation project. The LTTE wouldn’t have been able to enhance its fighting capabilities to wipe out a routine army patrol at Thinnaveli, Jaffna in July 1983, killing 13 men, including an officer, without Indian training. That was the beginning of the war that lasted for three decades.

Anti-India project

Dixit also made reference to the alleged Chinese role in the overall China-Pakistan project meant to fuel suspicions about India in Nepal and Bangladesh and the utilisation of the developing situation in Sri Lanka by the US and Pakistan to create, what Dixit called, a politico-strategic pressure point in Sri Lanka.

Unfortunately, Dixit didn’t bother to take into consideration Sri Lanka never sought to expand its armed forces or acquire new armaments until India gave Tamil terrorists the wherewithal to challenge and overwhelm the police and the armed forces. India remained as the home base of all terrorist groups, while those wounded in Sri Lanka were provided treatment in Tamil Nadu hospitals.

At the concluding section of the chapter, titled ‘AN INDOCENTRIC PRACTITIONER OF REALPOLITIK,’ Dixit found fault with Indira Gandhi for the Sri Lanka destabilisation project. Let me repeat what Dixit stated therein. The two foreign policy decisions on which she could be faulted are: her ambiguous response to the Russian intrusion into Afghanistan and her giving active support to Sri Lanka Tamil militants. Whatever the criticisms about these decisions, it cannot be denied that she took them on the basis of her assessments about India’s national interests. Her logic was that she could not openly alienate the former Soviet Union when India was so dependent on that country for defense supplies and technologies. Similarly, she could not afford the emergence of Tamil separatism in India by refusing to support the aspirations of Sri Lankan Tamils. These aspirations were legitimate in the context of nearly fifty years of Sinhalese discrimination against Sri Lankan Tamils.

The writer may have missed Dixit’s invaluable assessment if not for the Indian External Affairs Ministry presenting copies of ‘Makers of India’s Foreign Policy: Raja Ram Mohun Roy to Yashwant Sinha’ to a group of journalists visiting New Delhi in 2006. New Delhi arranged that visit at the onset of Eelam War IV in mid-2006. Probably, Delhi never considered the possibility of the Sri Lankan military bringing the war to an end within two years and 10 months. Regardless of being considered invincible, the LTTE, lost its bases in the Eastern province during the 2006-2007 period and its northern bases during the 2007-2009 period. Those who still cannot stomach Sri Lanka’s triumph over separatist Tamil terrorism, propagate unsubstantiated allegations pertaining to the State backing excesses against the Tamil community.

There had been numerous excesses and violations on the part of the police and the military. There is no point in denying such excesses happened during the police and military action against the JVP terrorists and separatist Tamil terrorists. However, sexual violence hadn’t been State policy at any point of the military campaigns or post-war period. The latest UN report titled ‘ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CONFLICT RELATED VIOLENCE IN SRI LANKA’ is the latest in a long series of post-war publications that targeted the war-winning military. Unfortunately, the treacherous Sirisena-Wickremesinghe Yahapalana government endorsed the Geneva accountability resolution against Sri Lanka in October 2015. Their despicable action caused irreversible damage and the ongoing anti-Sri Lanka project should be examined taking into consideration the post-war Geneva resolution.

By Shamindra Ferdinando ✍️

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoHistory of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine Kandana

-

Opinion18 hours ago

Opinion18 hours agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”