Features

The Island: Tough Journalism For Tough Times

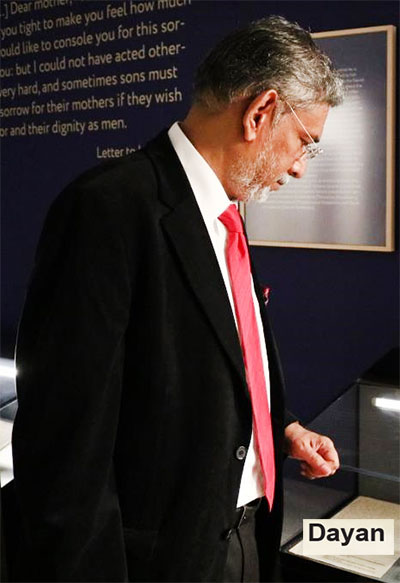

By Dr. Dayan Jayatilleka

Just weeks before turning 65, the age at which a third vaccine is mandatory in many countries, my first memory remains clear. It was of a man and a typewriter. The man was seated at the short side of a long table. He was dressed in a pair of light tan trousers, socks and buffed ‘pumps’. He wore a white sleeveless vest and a watch. I was in a playpen. My maternal grandmother was behind it. She was smiling benignly. The man was typing briskly.

It was my father. I called him Thaththa. They called him Mervyn. He worked in the newspapers. He was a journalist. In the tribute in the newspapers when he died in 1999, months from his 70th birthday, Mahinda Rajapaksa wrote that “Mervyn de Silva was undoubtedly the uncrowned media king of Sri Lanka”. Last year, Marwan Marcan-Markar of the Nikkei told me Mervyn was “an institution of South Asian journalism”.

From the birth of The Island until his own death, Mervyn wrote a weekly column for The Island under the pen-name Kautilya. The day after he died, The Island ran the news story on his death on the page one and the latest Kautilya column which he had handed in a few days before, in the Op-Ed page which was its usual home.

When I was a boy and an adolescent, Lake House had the finest collection of journalistic talent and personalities. The pages of the Lake House papers had the best minds and most vibrant debates. All that began to dry up a few years after the state takeover, with the change—the decline–epitomized by the firing of my father from the posts of editor-in-chief and editor. The energy in journalism then shifted outside the mainstream media to the periodicals and the regional press—the Lanka Guardian founded by Mervyn in 1978 and the Saturday Review in Jaffna.

The birth of The Island was the rebirth of the English-language mainstream press. The best of the old school journos and the most promising young ones tended to join The Island. The most seminal opinion-makers were found in its regular columns or as occasional contributors. The center of gravity of mainstream English-language journalism had shifted; found a home.

The Island

was not a place for journalists whose fiber wasn’t tough enough. Lake House had been founded in and for the struggle for Independence. The Island was born in more contentious times. It had to report on, reflect on and indeed simply reflect, a new, dark time of conflict and crisis, war and intervention, revolution and counterrevolution, assassination and terrorism. Or, more simply, the 1980s. Violent death, often on a large scale, was the main story; the dynamics which fed into and flowed from violent death.

The Island

was strong. Through the 30 years War against Prabhakaran and the Tigers, it was the paper that took over the patriotic role Lake House played in the Independence struggle. In the 21st century it fought against the appeasement of separatist-terrorism.

In the third decade of the 21st century, it hasn’t lost its temperament though it has aged like all of us, suffering the attrition of the continuing crisis. It has work to do as has the English-language newspapers as a whole. What we are witnessing now is in its own way as significant as the 1980s: the unprecedented proliferation of social movements; movements of social rather than solely political protest. The English-language press has to make those social protests intelligible to the English-language readership, while reflecting critically on both the state policies that have set them in motion as well as on the movements themselves– or the Movement itself.

Mervyn de Silva penned a message on the 15th anniversary of The Island. I am privileged to follow in his footsteps in undertaking the same task on its 40th anniversary.