Opinion

The epidemiology of violence

By Prof. Susirith Mendis

(First part of this article appeared in The Island Midweek Review of 05 June 2023)

Is civil disobedience violence or a prelude to violence?

Civil disobedience, by generally accepted definition, entails a deliberate breach of law (usually unjust), that is committed with the intention of communicating to a broad audience, including state authorities and the general public, the need for some legal or political change.

Mohandas Ramchand Gandhi internationalised the concept of non-violent struggle through non-violent civil disobedience (Sathyagraha and Sathyakriya) as an effective mode of modern political protests against the colonial rule of British in India. Gandhi’s Salt March was an act of civil disobedience – the principled refusal to comply with a law, at the risk of imprisonment or other punishment, in order to force a concession. Did the ‘aragalites’ envisage arrest and imprisonment at any time during their protests? Or were they of the firm belief that they are not breaking any law and therefore cannot and will not be arrested? Did they walk a thin red line or did they not?

Civil disobedience is a form of political protest. Martin Luther King exercised it in all his political actions by taking to the streets. But it is often emphasised that there are good pragmatic reasons for civil disobedience campaigns to adhere to non-violence.

It is useful for us to look at a recent example from France. Andreas Marcou describes this in his article titled “Violence, communication, and civil disobedience” in ‘Jurisprudence’ – an International Journal of Legal and Political Thought. He describes the events that took place in November 2018, when hundreds of thousands of French people took to the streets to protest President Emmanuel Macron’s planned tax hike for diesel and gas (déjà vu?). What began as a protest for fuel tax finally spiralled into multiple episodes of spasmodic violence. What commenced as non-violent protest within weeks of the initial protest, news outlets were brimming with pictures of burning cars, police in anti-riot gear clashing with protesters throwing projectiles, the Arc de Triomphe vandalised, and high street shops ransacked. With thousands of protesters and police officers injured, thousands were arrested and convicted, and several dead because of the protests. The current violence in Paris following the killing of a 17-year-old boy by the police is another example of the generally politically volatile French public.

Furthermore, Marcou goes on to describe how the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement that began largely as non-violent, there have been instances of clashes with police and counter-protesters, as well as looting and other damage to property. He says that the French protest and the resurgent Black Lives Matter movement “have once again brought forward debates about violence and disobedience”. Therefore, it is apparent that non-violent protest can qualify as civil disobedience. Some experts argue that some violent protests could be classified as civil disobedience. But we still need to find the ‘thin red line’ that demarcates civil disobedience from violent protests.

It is often debated that “violent civil disobedience” – though it sounds like an oxymoron – is justified in situations where “fundamentally illegitimate regimes” are violating human rights of citizens. For instance, even the killing of a genocidal dictator (such as Hitler or Pol Pot) when thousands of innocent lives are at stake, is arguably morally defensible. However, in the context of protests against a democratically elected legitimate regime, the use of violence is hardly justifiable. I would argue on the aforesaid basis, that the ‘GotaGoHome’ protests have justification only if they remained non-violent.

Justifiable violence

In self-defence

This is the most controversial and debatable aspect of violence. Often, we find that the perpetrators of violence use ‘justifiable violence’ as the excuse for their actions.

Andrea Borghini in an article in February 2019 titled “Can Violence be Just?” commences thus: “In some, probably most, circumstances it is evident that violence is unjust; but some cases appear more debatable to someone’s eyes: can violence ever be justified?

In its most basic form, violence is justified when it is personal counter-violence. If a person punches you in the face, it may seem justified to try and respond to that with counter physical violence – i.e., a form of self-defence. Borghini further argues that “In a more audacious version of the justification of violence in the name of self-defense, violence of any kind may be justified in reply to the violence of any other kind, provided there is a somewhat fair use of the violence exercised in self-defense.”

Political violence

Usually, political violence is a means to an end where the ‘end justifies the means’. Political violence by definition is said to be considered not as an end in itself. The concept of consequentialism would justify violence if the consequences were sufficiently ‘good’ to justify the harm of violence. Utilitarianism, on the other hand, would allow for the use of violence where utility or usefulness of violence is of benefit to society.

This may be countered by the argument that anarchic violence, though political, is often chaotic and directionless and the outcome or end is unclear.

Argument for the moral grounds of political violence have been enunciated by many philosophers. Political violence is justified in the situation in which the violence is employed as a necessary means to an end, in which all other ‘means’ have been exhausted and where the violence is for the restoration of democracy from authoritarianism or fascism.

Where in the spectrum of justifiable political violence does the ‘aragalaya’ fall into? Or is it justifiable in the context of an economic crisis precipitated by a multiplicity of factors – both external and internal – in a democratic sociopolitical milieu that was not authoritarian nor fascistic? Perhaps answers to these questions may lie in one’s political perspectives.

Revolutionary violence

Where in the spectrum of political violence can we put violence that has occurred during revolutions?

The major successful revolutions have been the Russian, Chinese and Cuban in our modern history. Then we have had the Iranian and Philippine revolutions; the revolutions in Nicaragua and some Latin American countries; and the ‘colour’ revolutions in the former Soviet-East European states. The latter have been qualitatively different from the former where street demonstrations have led to violence and regime change. Where do we put what happened in Iraq, Syria and Libya? In that sense, the ‘aragalaya’ has been the most non-violent with little or no state violence unleashed to save the ruling regime.

I remember reading somewhere, about Dr. Dayan Jayatilleke’s book and its theorisation of Fidel’s ethics of violence where he writes about three key elements – which are the avoidance of (i) targeting non-combatants, (ii) physical torture, and (iii) the execution of captives. This has not been true of all revolutions. The most notable being the execution of Czar Alexander and his family.

Morality and Ethics of violence

This brings us to another concept – the morality and ethics of violence. Since this article is getting longer than I first intended, I shall try to be as brief as possible. David Rapoport states that there are three prominent views on the morality of violence. They are: (1) the pacifist position, which states that violence is always immoral, and should never be used; (2) the utilitarian position – that violence can be used if it achieves a greater “good” for society; (3) a hybrid of these two views which both looks at what good comes from the use of violence, while also examining the types of violence used.

In a provocative thesis – ‘Virtuous Violence’ by Alan Page Fiske, an anthropologist at UCLA, and Tage Rai, a psychologist and post-doctoral scholar at Northwestern University, they conclude that “across cultures and history, there is generally one motive for hurting or killing: people are violent because it feels like the right thing to do. They feel morally obliged to do it.”

Can the perpetrators who attacked and killed 12 people in the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris on January 7th, 2015, justify themselves on the basis of the above argument? The two brothers who were responsible for the attack and killings later said that they “were defending Prophet Mohommed”.

Can the bombing of Afghanistan by the US Air Force with support from Britain, France, Australia, Canada and Germany, soon after the 9-11 bombing of the twin towers in New York be justified on the same basis?

Can the Russian invasion of Ukraine be justified on the basis of an existential threat to its territory and nationhood from the attempted expansion of NATO?

Can the attack on ‘aragalites’ in front of ‘Temple Trees’ justify the burning and looting of 70-odd houses all over Sri Lanka?

It can be all too easy to brand violence as evil, but increasingly, research is revealing this approach is being too simplistic and offers no effective means of reducing violence. A similar insight is drawn by the Harvard psychologist, Steven Pinker who argues that most perpetrators of violence throughout history are not pathological but motivated to act within their own moral framework.

Now the obvious question comes up. What is this ‘moral framework’? It obviously differs from culture to culture and societal norms of different communities. Is violence justified when defending the unarmed and unempowered? The issue of morality and ethics of violence is not as straightforward as we might wish to think. Each specific situation demands analysis of the morality of violence. We are left with an unanswered moral dilemma. “Is violence always wrong?”

Just War theory

The just war theory (JWT) is a doctrine of military ethics that aims to ensure that a war is morally justifiable through a series of criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just.

It is said that JWT can be traced as far back as to Ancient Egypt. The Chinese justified war only as a last resort and only if declared by the rightful sovereign. But they added the fallacious argument that the success of a military campaign was sufficient proof that the war had been righteous. This is not surprising as we find that this argument seems to be in play in modern times as well. The outcome of World Wars I and II and the Treaty of Versailles and the Nuremburg Trials are classic examples of the persistence of the Chinese argument for a righteous war.

The Mahabharata offers the first written discussions of a “just war” (dharma-yuddha or “righteous war”). In it, one of five ruling brothers (Pandavas) asks if the suffering caused by war can ever be justified. A long discussion then ensues between the siblings, establishing criteria like proportionality (chariots cannot attack cavalry, only other chariots; no attacking people in distress), just means (no poisoned or barbed arrows), just cause (no attacking out of rage), and fair treatment of captives and the wounded.

From the Islamic concept of jihad (Arabic: “striving”), or holy war, comes the concept of Muslim legal theory which is the only type of just war in their ‘rule book’.

Most wars are justified on one or another rationale. Those who go to war always have a justification. The US involvement in the Vietnam war and the current war between Russia and the Ukraine are contrasting cases from the ends of the political spectrum.

In conclusion

I have tried in this short essay to discuss violence as an anthropological entity with a spectrum of opinions and justifications. The debate/discussion will last as long as civilisation lasts. As long as we as humans will have our primaeval, atavistic ‘tribal’ propensities. As long as we are divided by class, caste, religion, race and nationhood.

The ‘aragalaya’ must necessarily fall into some slot in these myriad human propensities for violence and non-violence. As I said at the outset, there are a few unique features in what happened from April to July 2022. It began with a non-violent peaceful right to protest. The candle-lit vigils – mostly of the middle and upper-middle class – that almost immediately changed into a spasm of violence in Mirihana when a bus was torched. In the minds of some of them, their intentions were violent right from the beginning. But for others, it was justified, non-violent protests against a regime that had deteriorated fast into economic chaos leading to civil unrest.

So, to which slot exactly, can we put the ‘aragalaya’ in this ‘epidemiology of violence’? How spontaneous was it? Were there other players in the shadows who played ‘puppets on strings’? Were there external sources who funded the ‘aragalaya’? If so, what were their motivations? Was ‘regime change’ on their agenda? Did the circumstances of those heady events demand a regime change?

Did our predominant culture, the Buddhist ethos prevent serious violence on the part of the ‘aragalites’, and more pertinently on the part of the regime? Why was not a single shot fired into the air, and failing which into the crowd, when the Presidential Residence gates were breached? Why did the President slink away quietly by the back door into political oblivion? Do the current attempts at supressing dissent ‘by legal means’ portend of more violence to come?

We shall have to await a detailed and deep analysis of what happened in those critical months in 2022 in Sri Lanka to make better sense of what really happened a year ago.

Opinion

A puppet show?

After jog for the camera, wearing shorts in Jaffna, thanks to the freedom gained by the country being liberated from the clutches of the Tigers by the valiant efforts led by Mahinda Rajapaksa, President Anura Kumara Dissanayaka, said: “Some come past Sri Maha Bodhi and other Buddhist temples all the way to Jaffna to observe Sil, not to spread compassion but hatred.” When the need of the hour is reconciliation what an outrageous statement that was, to be made by the head of state! Will he say that the people of the North and the East bypass many Kovils straddling the area and come to Kataragama to spread hate? Probably not! His claim has become a hot topic of conversation.

Having lost a majority of the votes garnered from the North at the presidential and parliamentary elections, to the Tamil nationalist parties at the local government elections, President Dissanayake’s claim may well have been a pitiful attempt to recover lost ground in the North. But at what cost?

It all started with AKD’s refusal to refer to those brave service personnel who saved the unity and the integrity of the country as Rana Viruwo. Interestingly, the most devastating rebuke for this came from a Tamil MP, who is an avowed admirer of Prabhakaran, stating in Parliament that a Sinhala Rana Viruwa saved his life when he was about to be washed off in the flood waters resulting from Cyclone Ditwah. He teased the government by asking in ‘raw’ Sinhala Ei umbalata lejjada unta Rana Viruwo kiyanna? (Are you shy to call them war heroes?)

In addition to slinging mud at MR and harassing service personnel, there is no doubt whatsoever that AKD’s government is trying to harass any Tamil politicians who helped eradicate the Tigers. This fact is borne out by the treatment meted out to Douglas Devananda. Shamindra Ferdinando has explained this in his article, “EPDP’s Devananda and missing weapons supplied by Army” (The Island, 7 January).

NPP ministers publicly insult Buddhist monks, but whenever they are in trouble, they rush to Kandy to meet the Maha Nayakas, the latest being Harini’s visit. Instead of admitting the mistake and trying to make amends, the government went on, until it realised the futility in trying to justify the ‘Buddy’ episode. Excuses given by Harini to the Maha Nayakas, to say the least, were laughable. She had the audacity to say that though the questionable web link was printed in the textbook there were no instructions to click on it! She may continue as Prime Minister but can anyone who does not know what to do with a link or who is trying to encourage ten-year-olds to have e-buddies when the rest of the world is heading towards banning 16-year-olds from social media, continue to be the Minister of Education?

Number of MOUs/pacts signed with India, including defence, have not yet been disclosed even to Parliament. The Cabinet Spokesman once stated that the contents of those MOUs/pacts could not be divulged without the consent of India. Interestingly, we have had very frequent visits from VVIP politicians and top government officials from India, some at very short notice. One of them referred to these as ‘usual’ ones! However, what is unusual is that a party that shed a lot of blood of Sri Lankans for even selling ‘Bombay’ onions, is now in government and seems under Indian command. Perhaps, its transformation occurred when India sponsored a visit by AKD in early 2024, which helped him secure the presidency. Among the NPP’s election pledges, the most touted one was to reveal the mastermind behind the Easter Sunday attacks. It has been alleged in some quarters that India was behind the attacks. The NPP government’s silence about this speaks volumes!

It has transpired recently that it was Indian High Commissioner Gopal Baglay who pressured Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena in July 2022 to take over the presidency after the elected President was toppled by protesters, but many believe that it was a joint effort by the Indian HC and the ‘Viceroy’ who just left, after an overstay! It is an illegal act as pointed out in the editorial “Conspiracy to subvert constitutional order” (The Island, 22 January) and may be investigated by a future government, if elections are not postponed forever!

We seem to be watching a puppet show where many puppeteers outside are pulling the strings! Are we paying the price for electing a bunch of inexperienced politicians?

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana ✍️

Opinion

Remembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

Salute to a brave father-son

Cedric Martenstyn was a very affluent man. He owned a house in Colombo 7, valuable properties throughout the country, vehicles / speed boats and ran the lucrative business of importing Johnson and Evinrude Outboard Motors (OBM) and sold them to local fishermen and businessmen.

Cedric was the local agent for the OBMs, which were known for reliability and after-sales service, and among his customers were humble fishermen. He was fondly known as Sudu Mahattaya “(white Gentleman) by humble fishermen and he would often travel in his double cab across the country to meet his customers and solve their problems.

He had a loving wife and children. He was an excellent scuba diver, member of Sri Lanka Navy Practical Pistol Firing team and his knowledge of wildlife and reptiles was amazing.

A member of the Dutch Burgher community of Sri Lanka, he was a true patriot, who volunteered to protect country and people from terrorists. An old boy of S. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia, he was an excellent sportsman.

The founding father of Sri Lanka Army Commando Unit, Colonel Sunil Peris, was his classmate at S.Thomas’.

I first met Cedric when I was a very junior officer at Pistol Firing Range at Naval Base, Welisara. I helped him catch a poisonous snake in the Range. I think he carried that snake home in a bottle! That was the type of person Cedric was!

We became very close friends as we both loved “guns and fishing rods”. His experience and tactics in angling helped me catch much bigger Paraw (Trevallies) in the Elephant Rock area at the Trincomalee harbour. He was a dangerous man to live with at Trincomalee Naval Base wardroom (officers’ mess), because he had various live snakes kept in bottles and fed them with little frogs!

Even though he was a keen angler, he was keen to conserve endangered species both on land and in water. He spent days in Horton Plains and the Knuckles Mountain Range streams to identify freshwater species in Sri Lanka. Did you know there is an endangered freshwater fish species he found in Horton Plains and Knuckles Mountain Range has been named after him?

Feeding of snakes was an amusement to all our stewards at the wardroom at that time! They all gathered and watched carefully what Cedric was doing, keeping a safe distance to run away if the snake escaped. Our Navy stewards dare to enter Cedric’s cabin (room) at Trincomalee wardroom (officers’ mess), even keeping his tea on a stool outside his cabin door. One day pandemonium broke in the officers’ mess when Cedric announced that one snake escaped! We never found that snake, and that was the end of his hobby as the Commander Eastern Naval Area, at that time, ordered him to ” get rid of all snakes! Sadly, Cedric released all snakes to Sober Island that afternoon.

Cedric was a volunteer Navy officer, but still joined me (he was 47 years old then) to help SBS trainees (first and second batch) on boat handling and OBM maintenance in 1993, when I raised SBS. It was exactly 31 years ago!

The Arrow Boat

Being an excellent speed boat race driver and boat designer, he prepared the blueprint of the first “18-foot Arrow Boat” and supervised building it at a private Boat Yard in 1993. This 18- foot Arrow Boat was especially designed to be used in the shallow waters of the Jaffna lagoon, fitted 115 HP OBMs, and with two weapons he recommended; 40mm Automatic Grenade Launcher (AGL) and 7.62×51 mm General Purpose Machine Guns (GPMGs). In no time, we had highly trained and highly motivated four SBS men on board each Arrow Boat at Jaffna lagoon, and they were very effective.

Same hull (deep V hull) developed during the tenure of Admiral of the Fleet Wasantha Karannagoda, as Commander of the Navy, by Naval architects, with knowledge-gained through captured LTTE Sea Tiger boats, designed 23- foot Arrow Boats and implemented the “Lanchester Theory” (theory of battle of attrition at sea in littoral sea battles) to completely nullify LTTE’s superiority which it had gained with small craft and deadly suicide boats.

Thank you, the Admiral of the Fleet for understanding the importance of Arrow Boat design and mass production at our own boatyard at Welisara. Karannagoda, under whom I was fortunate to serve as Director Naval Operations, Director Maritime Surveillance and Director Naval Special Forces during the last stages (2006/7) of the Humanitarian Operations, always used to tell us “You cannot buy a Navy- you have to build one”! Thank you, Sir!

Cedric craft display at Naval Museum, Trincomalee

The Hero he was

When I was selected for my Naval War Course (Staff Course) conducted by the Pakistan Navy Staff College at Karachi, Pakistan, (now known as Pakistan Navy War College relocated at Lahore), Cedric took over the command (even though he was a VNF officer) as Commanding Officer of SBS.

Being one of the co-founders of this elite unit, he was the most suitable person to take over as CO SBS. He was loved by SBS officers and sailors. They were extremely happy to see him at Kilali or Elephant Pass, where SBS was deployed during a very difficult time of our recent history – fighting against terrorists during the 1996-97 period.

Motivated by father’s patriotism, his younger son, Jayson, who was a pilot working in the UK at that time, came back to Sri Lanka and joined the SLAF as an volunteer pilot to fly transport aircraft to keep an uninterrupted air link between Palaly (Jaffna) and Ratmalana (Colombo). Sometimes Jayson flew his beloved father on board from Palaly to Ratmalana. Cedric was extremely happy and proud of his son.

Tragically, young Jayson was killed in action in a suspected LTTE Surface-to-Air missile attack on his aircraft. Cedric was sad, but more determined to continue the fight against LTTE terrorists. He would also lead the rescue and salvage operation to identify the aircraft wreckage his son flew in. The then Navy Commander advised him to demobilise from VNF and look after his grieving family or join Naval Operations Directorate and work from Colombo which he vehemently refused. When I called him from Pakistan to convey my deepest condolences, he said, he would look after the “SBS boys”, he had no intention of leaving them alone at that difficult hour of our nation. That was Cedric. He was such a hero—a hero very few knew about!

The young officers, and sailors in SBS were of his sons’ age, and Cedric would not leave them even when he was facing a personal tragedy. He was a dedicated and courageous person.

Scientific name: Systomus Martenstyni

English name : Martenstyn’s Barb

Local name: Dumbara Pethiya

Sadly, like many who served our nation and stood against terrorists, Cedric would go on to be considered Missing In Action (MIA) following a helicopter crash off the seas of Vettalikani with Lt. Palihena (another brave SBS officer- KDU intake). He was returning to Point Pedro after visiting the SBS boys at Elephant Pass, Jaffna.

Cedric and his son, Jayson, will go down in history as a brave father-son duo who paid the supreme sacrifice for the motherland. MAY THEY REST IN PEACE ! Salute!

Commander Martenstyn was considered missing in action (MIA) on 22 January 1996 in the sea off Vettalaikerni, while returning to Palaly Air Force Base in an SLAF helicopter when it was lost to enemy fire. He was returning from visiting an SBS detachment in Elephant Pass near the Jaffna Lagoon. Considering his contribution to the war effort, his gallentry and valour in fighting the enemy, and his steadfast service to the Sri Lanka Navy in manufacturing Arrow Boats, and training the SBS, all SLN Arrow Boats were renamed ‘Cedric’ on his 70th Birthday.

(The writer is former Chief of Defence Staff and Commander of The Navy, and former Chairman of the Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd.)

By Admiral Ravindra

C Wijegunaratne

(Retired from Sri Lanka Navy)

Former Chief of Defence Staff and Commander of the Sri Lanka Navy,

Former Sri Lanka High Commissioner to Pakistan

Opinion

History of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine Kandana

According to legend, St. Sebastian was born at Narbonne in Gaul. He became a soldier in Rome and encouraged Marcellian and Marcus, who were sentenced to death, to remain firm in their faith. St. Sebastian made several converts; among them were master of the rolls Nicostratus, who was in charge of prisoners, and his wife Zoe, a deaf mute whom he cured.

Sebastian was named captain in the Roman army by Emperor Diocletian, as by Emperor Maximian when Diocletian went to the east. Neither knew that Sebastian was a Christian. When it was discovered that Sebastian was indeed a Christian, he was ordered to be executed. He was shot with arrows and left to die but when the widow of St. Castulas went to recover his body, she found out that he was still alive and nursed him back to health. Soon after his recovery, St. Sebastian intercepted the Emperor; denounced him for his cruelty to Christians and was beaten to death on the Emperor’s order.

St. Sebastian was venerated in Milan as early as the time of St. Ambrose. St. Sebastian is the patron of archers, athletes, soldiers, the Saint of the youths and is appealed to protection against the plagues. St. Ambrose reveals that the parents that young Sebastian were living in Milan as a noble family. St. Ambrose further says that Sebastian, along with his three friends, Pankasi, Pulvius and Thorvinus, completed his education successfully with the blessing of his mother, Luciana. Rev. Fr. Dishnef guided him through his spiritual life. From his childhood Sebastian wanted to join the Roman army. With the help of King Karnus, young Sebastian became a soldier and within a short span of time he was appointed as the Commander of the army of King Karnus. The Emperor Diocletian declared Christians the enemy of the Roman Empire and instructed judges to punish Christians who have embraced the Catholic Church. Young Sebastian, as one of the servants of Christ, converted thousands of other believers into Christians. When Emperor Diocletian revealed that Sebastian had become a Catholic, the angry Emperor ordered for Sebastian to be shot to death with arrows. After being shot by arrows, one of Sebastian supporters, Irane, treated him and cured him. When Sebastian was cured he went to Emperor Diocletian and professed his faith for the second time disclosing that he is a servant of Christ. Astounded by the fact that Sebastian is a Christian, Emperor Diocletian ordered the Roman army to kill Sebastian with club blows.

In the liturgical calendar of the Church, the feast of the St. Sebastian is celebrated on the 20th of January. This day is indeed a mini Christmas to the people of Kandana, irrespective of their religion. The feast commenced with the hoisting of the flag staff on the 11th of January at 4 p.m. at the Kandana junction, along the Colombo-Negombo road. There is a long history attached to the flag staff. The first flag staff, which was an areca nut tree, 25 feet tall, was hoisted by the Aththidiya family of Kandana, and today their descendants continue hoisting of the flag staff as a tradition. This year’s flag staff, too, was hoisted by the Raymond Aththidiya family. Several processions, originating from different directions, carrying flags, meet at this flag staff junction. The pouring of milk on the flag staff has been a tradition in existence for a long time. The Nagasalan band was introduced by a well-known Jaffna businessman that had engaged in business in Kandana in the 1950s. The famous Kandaiyan Pille’s Nagasalan group takes the lead, even today, in the procession. Kiribath Dane in the Kandana town had been a tradition from time immemorial.

According to available history from the Catholic archives and volume III of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka, the British period of vicariates of Colombo, written by Rev. Ft. Vito Perniola SJ, in 1806, states that the British government granted the freedom of conscious and religion to the Catholics in Ceylon and abolished all the anti-Catholic legislation enacted by the Dutch.

The proclamation was declared and issued on the 3rd of August 1796 by Colonel James Stuart, the officer commanding the British forces of Ceylon stated “freedom granted to Catholics” (Sri Lanka national archives 20/5).

Before the Europeans, the missioners were all Goans from South India. In the year 1834, on the 3rd of December, XVI Gregory the Pope, issued a document Ex Muwere pastoralis ministeric, after which the Ceylon Catholic Church was made under the South Indian Cochin diocese. Very Rev. Fr. Vincent Rosario, the Apostolic Vicar General, was appointed along with 18 Goan priests (The Oratorion Mission in Sri Lanka being a history of the Catholic Chruch 1796-1874 by Arthur C Dep Chapter 11 pg 12). Rev Fr. Joachim Alberto arrived in Sri Lanka as missionary on the 6th of March 1830 when he was 31 years old and he was appointed to look after the Catholics in Aluthkuru Korale, consisting Kandana, Mabole, Nagodaa and Ragama. There have been one Church built in 1810 in Wewala about three miles away from Kandana. The Wewala Chruch was situated bordering Muthurajawela which rose to fame for its granary. History reveals that the entire area was under paddy cultivation and most of them were either farmers or toddy tappers. History further reveals that there has been an old canal built by King Weera Parakrama Bahu. Later it was built to flow through the Kelani River, and Muthurajawela, up to Negombo, which was named as the Dutch Canal (RL Brohier historian). During the British time this canal was named as Hamilton Canal and was used to transport toddy, spices, paddy and tree planks of which tree planks were stored in Kandana. Therefore, the name Kandana derives from “Kandan Aana”.

Rev. Fr. Joachim Alberto purchased a small piece of land, called Haamuduruwange watte, at Nadurupititya, in Kandana, and put up a small cadjan chapel and placed a picture of St. Sebastian for the benefit of his small congregation. In 1837, with the help of the devotees, he dug a small well where the water was used for drinking and bathing and today this well is still operative. He bought several acres of land, including the present cemetery premises. Moreover, he had put up the Church at Kalaeliya in honour of his patron St. Joachim where his body has been laid to rest according to his wish of the Last Will attested by Weerasinghe Arachchige Brasianu Thilakaratne. Notary Public, dated 19th July 1855. The present Church was built on the property bought on the 13th of August 1875 on deed no. 146 attested by Graciano Fernando. Notary Public of the land Gorakagahawatta Aluthkuru Korale Ragam Pattu in Kandana within the extend ¼ acre from and out of the 16 acres. According to the old plan number 374 made by P.A. H. Philipia, Licensed surveyor on the 31st of January 195, 9 acres and 25 perches belonged to St. Sebastian Church. However, today only 3 acres, 3 roods and 16.5 perches are left according to plan number 397 surveyed by the same surveyor, while the rest had been sold to the villagers. According to the survey conducted by Orithorian priest on the 12th of February 1844 there were only 18 school-going Catholic students in AluthKuru Korale and only one Antonio was the teacher for all classes. In 1844 there was no school at Kandana (APF SCG India Volume 9829).

According to Sri Lanka National Archives (The Ceylon Almanac page 185) in the year 1852 there were 982 Catholics Male 265, female 290, children 365, with a total of 922. According to the census reports in 2014, prepared by Rev. Ft. Sumeda Dissanayake TOR, the Director Franciscan Preaching group, Kadirana Negombo a survey revealed that there are 13,498 Catholics in Kandana.

According to the appointment of the Missionaries in the year 1866-1867 by Bishop Hillarien Sillani, Rev. Fr. Clement Pagnani OSB was sent to look after the missions in Negoda, Ragama, Batagama, Thudella, Kandana, Kala Eliya and Mabole. On the 18th of April 1866, the building of the new Church commenced with a written agreement by and between Rec. Fr. Clement Pagnani and the then leaders of Kandana Catholic Village Committee. This committee consisted of Kanugalawattage Savial Perera Samarasinghe Welwidane, Amarathunga Arachchige Issak Perera Appuhamy, Jayasuriya Arachchige Don Isthewan Appuhamy, Jayasuriya Appuhamylage Elaris Perera Muhuppu, Padukkage Andiris Perera Opisara, Kanugalawattage Peduru Perera Annavi and Mallawa Arachchige Don Peduru Appujamy. The said agreement stated that they will give written undertaking that their labour and money will be utilised to build the new Church of St. Sebastian and if they failed to do so they were ready to bear any punishment which will be imposed by the Catholic Church.

Rev. Fr. Bede Bercatta’s book “A History of the Vicariate of Colombo page 359” says that Rev. Fr. Stanislaus Tabarani had problems of finding rock stones to lay the foundation. He was greatly worried over this and placed his due trust in divine providence. He prayed for days to St. Sebastian for his intercession. One morning after mass, he was informed by some people that they had seen a small patch of granite at a place in Rilaulla, close to the Church premises, although such stones were never seen there earlier, and requested him to inspect the place. The parish priest visited the location and was greatly delighted as his prayers has been answered. This small granite rock amount provided enough granite

blocks for the full foundation of the present church. This place still known as “Rilaulla galwala”. The work on the building proceeded under successive parish priests but Rev. Fr. Stouter was responsible for much of it. The façade of the Church was built so high that it crashed on the 2nd of April of 1893. The present façade was then built and completed in the year 1905. The statue of St. Sebastian, which is behind the altar, had been carved off a “Madan tree”. It was done by a Paravara man, named Costa Mama, who was staying with a resident named Miguel Baas a Ridualle, Kandana. This statue was made at the request of Pavistina Perera Amaratunge, mother of former Member of Parliament gatemuadliyer D. Panthi Jayasuirya. The Church was completed during the time of Rev. Fr. Keegar and was blessed by then Archbishop of Colombo Dr. Anthony Courdert OMI on the 20th of January 1912. In 1926, Rev. Fr. Romauld Fernando was appointed as the parish priest to the Kandana Church. He was an educationalist and a social worker. Without any hesitation he can be called as the father of education to Kandana. He was the pioneer to build three schools in Kandana: Kandana St. Sebastian Boys School, Kandana St. Sebastian English Girls School and, the Mazenod College Kandana. Later he was appointed as the Principal of the St. Sebastian Boys English School. He bought a property at Kandana, close to Ganemulla Road, and started De Mazenod College. Later, it was given officially to the Christian Brothers of Sri Lanka, by then Archbishop of Colombo, Peter Mark. In 1931, there were 300 students (history of De Lasalle brothers by Rev. Fr. Bro Michael Robert). Today, there are over 3,500 students and is one of the leading Catholic schools in Sri Lanka. In 1924, one Karolis Jayasuriya Widanage donated two acres to build De Mazenod College for its extension.

The frist priest from Kandana to be ordained was Rev. Fr. William Perera in 1904. With the help of Rev. Fr. Marcelline Jayakody, he composed the famous hymn “the Vikshopa Geethaya”, the hymn of our Lady of Sorrow.

The Life story of St. Sebastian was portrayed through a stage play called “Wasappauwa” and the world famous German passion play Obar Amargavewchi whichwas a sensation was initiated by Rev. Fr. Nicholas Perera. Legend reveals that in the year 1845 a South Indian Catholic, on his way to meet his relatives in Colombo, had brought down a wooden statue of St. Sebastian, one and half feet tail, to be sold in Sri Lanka. When he reached Kalpitiya he had unexpectedly contracted malaria. He had made a vow at St. Anne’s Church, Thalawila, expecting a full recovery. En route to Colombo, he had come to know about the Church in Kandana and dedicated to St. Sebastian. In the absence of the then parish Priest Rev. Fr. Joachim Alberto, the Muhuppu of the Church, with the help of the others, had agreed to by the statue for 75 pathagas (one pahtaga was 75 cent). Even though the seller had left the money in the hands of the “Muhuppu” to be collected later, he never returned.

On the 19th of January 2006, Archbishop Oswald Gomis declared St. Sebastian Church as “St. Sebastian Shrine” by way of a special notification and handed over the declaration to Rev. Fr. Susith Perera, the Parish Priest of Kandana.

On the 12th of January 2014, Catholics in Sri Lanka celebrated the reception of a reliquary containing a fragment of the arm of St. Sebastian. The reliquary was gifted from the administrator of the Basilica of St. Anthony of Padua and was brought to Sri Lanka by Monsignor Neville Perera. His Eminence Malcolm Cardinal Ranjit, Archbishop of Colombo, accompanied by priests and a large gathering, received the relic at the Katunayake International Airport, and brought it to Kandana, led by a procession, and was enthroned at the St. Sebastian Shrine.

Rev. Fr. Srinath Manoj Perera, the present administrator of the shrine, and assistant Priest Rev. Fr. Asela Mario, have finalised all arrangements to conduct the feast of St. Sebastian in a grand scale.

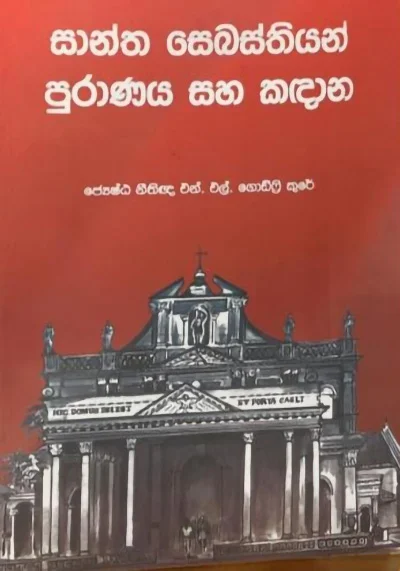

The latest book, written by Senior Lawyer Godfrey Cooray, named “Santha Sebastian Puranaya Saha Kandana” (The history of St. Sebastian and Kandana), was launched at De La Salle Auditorium, De Mazenod College, Kandana.

The Archbishop of Colombo His Eminence Most rev. Dr. Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith was the Chief Guests at the event.

The book discusses about the buried history of Muthurajawela and Aluth Kuru Korale civilisation, the history of Kandana and St. Sebastian. The author discusses the historical and archaeological values and culture.

158th Annual Feast of St. Sebastian’s National Shrine, Kandana, will be held on 20th of January 2026. On the 19th of January, Monday, Solemn Vespers were presided by His Lordship most Rev. Dr. Maxwell Silva Auxiliary Bishop of Colombo.

Festive High Mass will be presided by His Lordship Most Rev. Dr. J. D. Anthony, The Auxiliary Bishop of Colombo, on the 20th of January at 8pm.

By Godfrey Cooray

Senior Attorney -at -Law,

Former Ambassador to Norway and Finland

President, National Catholic Writers’ Association

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders