Features

The Aftermath of Empire – Reappraisal and Reconciliation – (Part 2)

by Professor Chandra Wickramasinghe*

Continued from last week

The author is an Honorary Professor at the University of Buckingham, UK, at the University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka, and also at the National Institute of Fundamental Studies in Sri Lanka.

He was a former Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge, Staff Member of the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, and former Professor at Cardiff University. He is a pioneer of the discipline of Astrobiology and the author of over 450 scientific papers and some 35 books.

Several generations of British historians, archaeologists and naturalists devoted their entire lives to tirelessly exploring the multiplicity of wonders of India. Studies of the subcontinent’s natural history, archaeology and anthropology are just a few scientific disciplines that enormously benefited from the imperial encounter. The introduction of greenhouses, zoological and botanic gardens to the Western world and much else came directly as a result of the colonial venture.

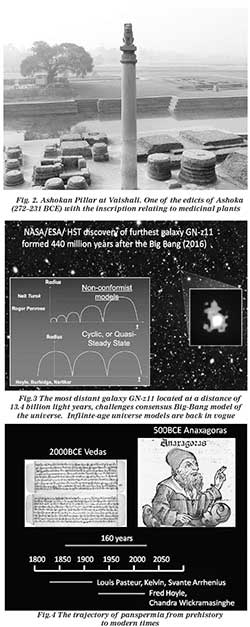

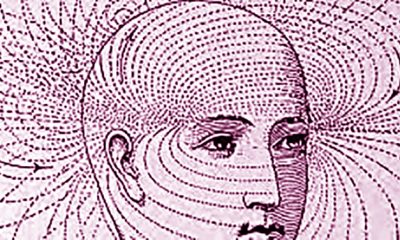

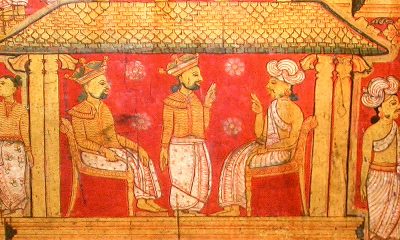

One discovery of great importance is worthy of mention. A large number of stone pillars and columns bearing mysterious inscriptions in a hitherto undeciphered Brahmi script had been scattered across the length and breadth of India and, rather strangely, gone unnoticed for centuries. In the 1830’s it was an English Philologist and scholar James Prinsep (1799-1840) who successfully deciphered these inscriptions. The edicts written in the Bhrami language mentioned a King Devanampriya Piyadasi which Prinsep had initially assumed was a Sri Lankan king. He was later to discover a Pali text from Sri Lanka from which he was able to connect the title Piyadasi with Ashoka, and thus was revealed for a first time a long-hidden secret of Indian history – the life and times of Emperor Ashoka who had reigned between 268 and 232 BCE. Ashoka is famous as the Indian monarch who became a Buddhist and unified a vast part of the Indian subcontinent into a single empire ruling it according to Buddhist principles. H.G. Wells in his “Outline of World History” said of Ashoka that amid tens of thousands of names of monarchs, “Ashoka shines, shines almost alone, a star”.

In the 1920’s it was again thanks to British archaeologists that we owe the next major discovery – the unravelling of the great Indus valley civilizations of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro which represents another long-hidden chapter in the prehistory of the Indian subcontinent stretching back to the third millennium BCE. We already had knowledge from Mesopotamian records of a vigorous trade in lapis lazuli that existed between empires in the Mesopotamia and India, but now we could link this precisely with the Indus valley civilizations.

In the 1920’s it was again thanks to British archaeologists that we owe the next major discovery – the unravelling of the great Indus valley civilizations of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro which represents another long-hidden chapter in the prehistory of the Indian subcontinent stretching back to the third millennium BCE. We already had knowledge from Mesopotamian records of a vigorous trade in lapis lazuli that existed between empires in the Mesopotamia and India, but now we could link this precisely with the Indus valley civilizations.

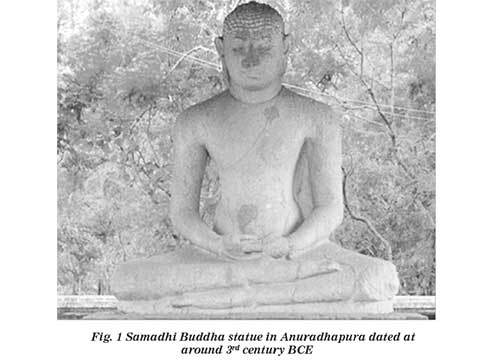

Unravelling a Buddhist heritage

A few British Civil Servants who were posted in Ceylon in the 19th century became assiduous students of Buddhist texts and wrote extensively and enthusiastically about Buddhism. Thomas William Rhys David (1843-1922) was one such scholar who found himself posted as Government Agent near the historic ancient city of Anuradhapura. There he became actively involved in archaeological excavations that led to the discovery of a vast number of inscriptions and manuscripts relating to Buddhism and this triggered his interest. He soon became a formidable Pali scholar, translated many Buddhist Pali texts into English and also wrote extensive commentaries on Buddhism that are still being read today.

The colonial response to Buddhism on the whole had been positive throughout the time of the Empire. H.G. Wells (1866-1946) in his “Outline of World History” writes of Buddhism thus:

“Many of our best modern ideas are in closest harmony with it. All the miseries and discontents of life are due, he (the Buddha) taught, to selfishness. Selfishness takes three forms – one, the desire to satisfy the senses; second, the craving for immortality; and the third the desire for prosperity and worldliness. Before a man can become serene he must cease to live for his senses or himself. Then he merges into a great being. Buddha in a different language called men to self-forgetfulness five hundred years before Christ. In some ways he was nearer to us and our needs. Buddha was more lucid on our individual importance in service than Christ, and less ambiguous upon the question of personal immortality.”

The amazing degree of concordance between Buddha’s view of consciousness and modern post-Jungian ideas in psychology were discussed by me and Daisaku Ikeda in our dialogue many years ago. The practice of Buddhist meditation is becoming increasingly popular in the West today because of its potential to yield mental and physical health benefits. Such practices, however, are looked upon with suspicion by many – now and in the past – as heathen primitive rituals that challenge the cannon of Christian faith. Such a narrow view cannot be interpreted as being any other than a component of racial thinking that prevailed throughout the period of British imperialism and filters down even into our post-colonial modern era.

Buddhist cosmology

In matters relating to cosmology and life in the Universe ideas from Buddhist as well as earlier Vedic traditions have run contrary to the canonical Western world-view. For instance, in the cosmology described in the Anguttara Nikaya (a Buddhist text dated at around the 1st century BCE) it is stated thus:

“As far as these suns and moons revolve, shedding their light in space, so far extends the thousand-fold world system. In it there are a thousand suns, a thousand moons, a thousand inhabited Earths and a thousand heavenly bodies. This is called the thousand-fold minor world system….”

It then goes on to define a hierarchy of world systems, referring to the entire universe as “this sphere of million, million world systems”. Similar views do not dominate scientific thinking in Europe until after the Copernican revolution in the 17th century of the common era. Today, with the recent discoveries of exoplanets in the past decade, the total number of exoplanetary systems in our Milky Way galaxy alone is estimated to exceed 100 billion.

As far back as the first millennium BCE a school of atomism similar to that of Democritus was founded in India, the most important proponent of this school being a philosopher named Kanada (600 BCE). The idea was that atoms are point-sized, indivisible and eternal, each possessing a distinct property and individuality. These concepts were developed further by a burgeoning Buddhist school of atomism that flourished in the 7th century CE.

Aryabhata (476-550CE) was perhaps the first Indian astronomer in the modern mould who discovered an approximation of pi to six significant figures and also correctly maintained that the planets and the Moon shine by reflected sunlight. He also correctly inferred from observations that the daily motion of the stars in the celestial sphere is due to Earth’s rotation about its axis.

From both archaeological and later historical evidence there is no doubt that high levels of advancement in science and technology had been achieved in India long before Aryabhata going back to at least the second millennium before the common era. Vedic Sanskrit texts dated at the 8th century BCE refer to Pythagorean triples (eg. (3,4,5 (5,12,13), (8,15,17)) and display a knowledge of Pythagoras theorem. One of the earliest Indian astronomical texts (Vedānga Jyotiṣa) dates from 1400–1200 BCE, with the currently extant form dating possibly from 700–600 BCE. This latter timespan also corresponds to the dating of the most ancient known “university” in the world, Takshashila in India, which was a centre first of Hindu and later Buddhist scholarship.

Ayurveda and plant-based pharmaceuticals

Developments in the field of ayurvedic plant-based medicine, and including reports of surgical interventions, have been recorded in a variety of sources from the earliest times. In one of the Ashokan pillars (272-231BCE), to which I have already referred, an edict reads: “Everywhere King Piyadasi (Ashoka) erected two kinds of hospitals, hospitals for people and hospitals for animals. Where there were no healing herbs for people and animals, he ordered that they be bought and planted.” There also exist many thousands of ayurvedic texts both in India and Sri Lanka with extensive lists of medicinal herbs and their alleged benefits for curing various ailments. The result of four centuries of colonial rule has unfortunately been to relegate this vast legacy to the “archive of curiosity”.

The few ayurvedic physicians who now practice in India and Sri Lanka still rely on time-hallowed anecdotal accounts of the efficacy of their plant-based medicines. The correct procedure will be for western science to fully explore these claims with chemical analysis and trials, but this has not yet been done. It should be recalled in this context that many drugs currently used in western medicine are indeed derived from plants – aspirin, quinine, digitalis, morphine, codeine – are just a few. It is hard to imagine the medical legacy that would follow from a complete investigation of the thousands of claimed herbal remedies that still remain unexamined.

Transition from ancient to modern science

I have already mentioned the knowledge of land surveying technologies and irrigation schemes that was evident in the Indus valley civilizations of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa; and these and other technological developments have also been found elsewhere in India and in neighbouring Sri Lanka throughout the period from the beginning of the common era until the time of the arrival of the British in 1600CE.

When the British arrived in India the difference in technological development between Britain and the subcontinent was arguably marginal. Handlooms and weaving technology that were developed and used in Bengal made India (run by the Moghuls) one of the richest countries of the world at this time. In a real sense it could be maintained that the technological advancement of the West took place at the cost of the continued impoverishment of India.

From the beginning of the 20th century many Indian scientists who were trained in British Universities and laboratories made highly significant contributions to the progress of science furthering the dominant scientific paradigms of Western science. A common feature of all these scientists is that their corpus of work supported and did not in any way challenge the major accepted paradigms of the day. Their achievements were thus thought to be a continuing tribute to the prevailing and predominant traditions of western science, and so were readily acknowledged and rewarded. However serious difficulties can arise whenever an ethnically non-European scientist hailing from an ex-colony dares to challenge a reigning paradigm of Western science.

Clash of Orthodoxy and Heresy

It should occasion no surprise to find that most important advances in science with regard to fundamental of issues concerning the Universe and Life have always been subject to cultural and religious constraints. Thus, in the 19th century the unfolding facts of geology that yielded an age of the Earth of some 4 billon years came into sharp conflict with Biblical chronologies of mere thousands of years, and this had initially caused great angst in some circles. Likewise, the facts of biological evolution that were unravelled after Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species was published in 1859 continued to disturb conventional beliefs for several decades.

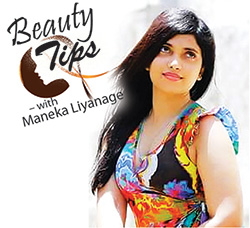

As already mentioned Buddhist and earlier Vedic cosmologies can be interpreted as being consistent with many aspects of modern and post-modern scientific thought. There are also fundamental differences that can cause consternation in a Western scientific context. In Vedic cosmology the universe is thought to be infinite in spatial extent and cyclic in time– strikingly reminiscent of the modern versions of oscillating universe models. In this context it is worth noting that the currently favoured Big-Bang theory of the Universe with an age of 13.8 billion years is by no means absolutely proved. The very recent discovery of a galaxy designated GN-z11 located at a distance of 13.4 billion light years (implying its formation just 420 million years after the posited Big Bang origin of the Universe) poses serious problems for the current consensus view of cosmology.

Recently Nobel Laureate Roger Penrose has come in among the select band of dissenters from the standard view of a unique Big Bang origin of the Universe 13.8 billion years ago. In a theory called the “conformal cyclic cosmology” Penrose postulates that the universe undergoes an infinite number of cycles in which the Big Bang event 13.8 billion years ago is the most recent cycle of which we are a part – a result strikingly in accord with ancient Vedic and Indian cosmology.

The inescapable fact of Panspermia

Finally, I turn to the age-old problem of our own origins – how we, humans and indeed all of life, came to be. This question has been approached in a multitude of different ways, embracing superstition, religion, philosophy and eventually science. The ideas that prevailed throughout ancient India involved the concept of life being an integral part of the structure of the universe – a view closely aligned to the ideas of panspermia discussed in the West by pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Anaxoragas of Clazomenae who lived around 500BCE. Panspermia implies that “seeds of life” are eternally present in the cosmos and take root whenever and wherever the condition permit.

This concept was vigorously rejected in the Western tradition in favour of the ideas of the more influential Greek philosopher Aristotle in the 3rd century BCE. Aristotle proposed instead that life must arise from non-living inorganic matter whenever the right conditions prevailed, and he cited many instances that were incorrectly regarded as supportive evidence, the most graphic being the statement of “fireflies emerging from a mixture of warm earth and morning dew”. Over a millennium and a half later Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1272) essentially co-opted Aristotelian philosophy into church doctrine, so that dissent from any component of it thereafter was effectively construed as heresy. The Aristotlean doctrine of “Spontaneous Generation” was transformed into “Abiogenesis” in modern terms and continues to dominate Western science almost to the present day.

Attempts to re-examine panspermia in the West began in earnest with the French biologist Louis Pasteur in the early 1860’s. Pasteur showed in the laboratory what was already known for larger visible life forms – that life is always derived from pre-existing life of a similar kind. This casual chain of events – life-from-life – is true not only for lifeforms existing today but it is also true throughout the entire record of fossilised life on the Earth. The question that next arises is: when and where this connection cease to operate. The answer could be never – so this then naturally leads to panspermia.

Following the experiments of Pasteur, panspermia came at last to be championed by many contemporary physicists in the late 19th century.

Lord Kelvin declared: “Dead matter cannot become living without coming under the influence of matter previously alive. This seems to me to be as sure a teaching of science as the law of gravitation….”

And the German physicist Herman von Helmholtz wrote in 1874:

“It appears to me a fully correct scientific procedure, if all our attempts fail to cause the production of organisms from non-living matter, to raise the question whether life has ever arisen, whether seeds have not been carried from one planet to another…”.

A similar position was also championed a few years later by the Nobel prize-winning Chemist Svante Arrhenius in his 1908 book Worlds in the Making. But all this enthusiasm was transient. On the basis of poorly designed experiments concerning limits to the viability of microbes in space, the situation soon reverted, and spontaneous generation and abiogenesis came back into vogue.

In the past five decades abiogenesis was confronted with a formidable array of new facts from astronomy, geology, space science and molecular biology, all of which challenged its validity. On the other hand, an ever-increasing number of predictions of panspermia has come to be verified to an astounding degree of precision. Wrong theories do not perform in this way, so it soon became amply clear that panspermia’s star was on the ascendant! The sociology of science now took over: the triumphs of panspermia over rival models began to irritate an ever-increasing body of scientists. This was aggravated by the fact that all attempts to demonstrate the validity of abiogenesis in the most advanced laboratories in the world consistently led to dismal failure.

The trajectory of panspermia from its early roots in the Vedas through to Anaxoragas in the 5th century BCE and into modern times is sketched in Fig.4. The last phase following on from Pasteur led up to the work of the present writer, Fred Hoyle and many collaborators. This unfolding scientific drama is well-documented in a very large number of scientific papers and recent books.

What I would like to reiterate by way of conclusion is that the body of objective scientific evidence in favour of cometary panspermia and against abiogenesis is now compelling and overwhelming. The main reason that this new world view has yet to enter mainstream thinking, and even become more widely known, may be simply because its principal proponent (the present writer) is seen as a heathen and a former colonial subject. In what could be seen as the most egregious travesty of justice serious attempts are being made to “steal” our well-documented priority on these ideas in recent publication of similar ideas but with a deliberate omission of any reference to pioneering work over the past 40 years. In my view overt racism including antagonism for what is seen to be an alien concept is the only conceivable explanation for this conduct. This explanation also provides the only reason for why a long-overdue paradigm shift from planet-centred life to cosmic-centred life – a paradigm shift which is potentially of the most profound importance across the whole of science – is being delayed.

The long colonial encounter between “West” and “East” that began in the 15th and 16th centuries ending barely seven decades ago has in every sense shaped the modern world. Many scars have been left, however, and a priority of the ongoing decolonisation process must not only be to expand on the legacy of this long experience but also to heal its wounds.

Features

Acid test emerges for US-EU ties

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen addressing the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on Tuesday put forward the EU’s viewpoint on current questions in international politics with a clarity, coherence and eloquence that was noteworthy. Essentially, she aimed to leave no one in doubt that a ‘new form of European independence’ had emerged and that European solidarity was at a peak.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen addressing the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland on Tuesday put forward the EU’s viewpoint on current questions in international politics with a clarity, coherence and eloquence that was noteworthy. Essentially, she aimed to leave no one in doubt that a ‘new form of European independence’ had emerged and that European solidarity was at a peak.

These comments emerge against the backdrop of speculation in some international quarters that the Post-World War Two global political and economic order is unraveling. For example, if there was a general tacit presumption that US- Western European ties in particular were more or less rock-solid, that proposition apparently could no longer be taken for granted.

For instance, while US President Donald Trump is on record that he would bring Greenland under US administrative control even by using force against any opposition, if necessary, the EU Commission President was forthright that the EU stood for Greenland’s continued sovereignty and independence.

In fact at the time of writing, small military contingents from France, Germany, Sweden, Norway and the Netherlands are reportedly already in Greenland’s capital of Nook for what are described as limited reconnaissance operations. Such moves acquire added importance in view of a further comment by von der Leyen to the effect that the EU would be acting ‘in full solidarity with Greenland and Denmark’; the latter being the current governing entity of Greenland.

It is also of note that the EU Commission President went on to say that the ‘EU has an unwavering commitment to UK’s independence.’ The immediate backdrop to this observation was a UK decision to hand over administrative control over the strategically important Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia to Mauritius in the face of opposition by the Trump administration. That is, European unity in the face of present controversial moves by the US with regard to Greenland and other matters of contention is an unshakable ‘given’.

It is probably the fact that some prominent EU members, who also hold membership of NATO, are firmly behind the EU in its current stand-offs with the US that is prompting the view that the Post-World War Two order is beginning to unravel. This is, however, a matter for the future. It will be in the interests of the contending quarters concerned and probably the world to ensure that the present tensions do not degenerate into an armed confrontation which would have implications for world peace.

However, it is quite some time since the Post-World War Two order began to face challenges. Observers need to take their minds back to the Balkan crisis and the subsequent US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq in the immediate Post-Cold War years, for example, to trace the basic historic contours of how the challenges emerged. In the above developments the seeds of global ‘disorder’ were sown.

Such ‘disorder’ was further aggravated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine four years ago. Now it may seem that the world is reaping the proverbial whirlwind. It is relevant to also note that the EU Commission President was on record as pledging to extend material and financial support to Ukraine in its travails.

Currently, the international law and order situation is such that sections of the world cannot be faulted for seeing the Post World War Two international order as relentlessly unraveling, as it were. It will be in the interests of all concerned for negotiated solutions to be found to these global tangles. In fact von der Leyen has committed the EU to finding diplomatic solutions to the issues at hand, including the US-inspired tariff-related squabbles.

Given the apparent helplessness of the UN system, a pre-World War Two situation seems to be unfolding, with those states wielding the most armed might trying to mould international power relations in their favour. In the lead-up to the Second World War, the Hitlerian regime in Germany invaded unopposed one Eastern European country after another as the League of Nations stood idly by. World War Two was the result of the Allied Powers finally jerking themselves out of their complacency and taking on Germany and its allies in a full-blown world war.

However, unlike in the late thirties of the last century, the seeming number one aggressor, which is the US this time around, is not going unchallenged. The EU which has within its fold the foremost of Western democracies has done well to indicate to the US that its power games in Europe are not going unmonitored and unchecked. If the US’ designs to take control of Greenland and Denmark, for instance, are not defeated the world could very well be having on its hands, sooner rather than later, a pre-World War Two type situation.

Ironically, it is the ‘World’s Mightiest Democracy’ which is today allowing itself to be seen as the prime aggressor in the present round of global tensions. In the current confrontations, democratic opinion the world over is obliged to back the EU, since it has emerged as the principal opponent of the US, which is allowing itself to be seen as a fascist power.

Hopefully sane counsel would prevail among the chief antagonists in the present standoff growing, once again, out of uncontainable territorial ambitions. The EU is obliged to lead from the front in resolving the current crisis by diplomatic means since a region-wide armed conflict, for instance, could lead to unbearable ill-consequences for the world.

It does not follow that the UN has no role to play currently. Given the existing power realities within the UN Security Council, the UN cannot be faulted for coming to be seen as helpless in the face of the present tensions. However, it will need to continue with and build on its worldwide development activities since the global South in particular needs them very badly.

The UN needs to strive in the latter directions more than ever before since multi-billionaires are now in the seats of power in the principle state of the global North, the US. As the charity Oxfam has pointed out, such financially all-powerful persons and allied institutions are multiplying virtually incalculably. It follows from these realities that the poor of the world would suffer continuous neglect. The UN would need to redouble its efforts to help these needy sections before widespread poverty leads to hemispheric discontent.

Features

Brighten up your skin …

Hi! This week I’ve come up with tips to brighten up your skin.

Hi! This week I’ve come up with tips to brighten up your skin.

* Turmeric and Yoghurt Face Pack:

You will need 01 teaspoon of turmeric powder and 02 tablespoons of fresh yoghurt.

Mix the turmeric and yoghurt into a smooth paste and apply evenly on clean skin. Leave it for 15–20 minutes and then rinse with lukewarm water

Benefits:

Reduces pigmentation, brightens dull skin and fights acne-causing bacteria.

* Lemon and Honey Glow Pack:

Mix 01teaspoon lemon juice and 01 tablespoon honey and apply it gently to the face. Leave for 10–15 minutes and then wash off with cool water.

Benefits:

Lightens dark spots, improves skin tone and deeply moisturises. By the way, use only 01–02 times a week and avoid sun exposure after use.

* Aloe Vera Gel Treatment:

All you need is fresh aloe vera gel which you can extract from an aloe leaf. Apply a thin layer, before bedtime, leave it overnight, and then wash face in the morning.

Benefits:

Repairs damaged skin, lightens pigmentation and adds natural glow.

* Rice Flour and Milk Scrub:

You will need 01 tablespoon rice flour and 02 tablespoons fresh milk.

Mix the rice flour and milk into a thick paste and then massage gently in circular motions. Leave for 10 minutes and then rinse with water.

Benefits:

Removes dead skin cells, improves complexion, and smoothens skin.

* Tomato Pulp Mask:

Apply the tomato pulp directly, leave for 15 minutes, and then rinse with cool water

Benefits:

Controls excess oil, reduces tan, and brightens skin naturally.

Features

Shooting for the stars …

That’s precisely what 25-year-old Hansana Balasuriya has in mind – shooting for the stars – when she was selected to represent Sri Lanka on the international stage at Miss Intercontinental 2025, in Sahl Hasheesh, Egypt.

That’s precisely what 25-year-old Hansana Balasuriya has in mind – shooting for the stars – when she was selected to represent Sri Lanka on the international stage at Miss Intercontinental 2025, in Sahl Hasheesh, Egypt.

The grand finale is next Thursday, 29th January, and Hansana is all geared up to make her presence felt in a big way.

Her journey is a testament to her fearless spirit and multifaceted talents … yes, her life is a whirlwind of passion, purpose, and pageantry.

Raised in a family of water babies (Director of The Deep End and Glory Swim Shop), Hansana’s love affair with swimming began in childhood and then she branched out to master the “art of 8 limbs” as a Muay Thai fighter, nailed Karate and Kickboxing (3-time black belt holder), and even threw herself into athletics (literally!), especially throwing events, and netball, as well.

A proud Bishop’s College alumna, Hansana’s leadership skills also shone bright as Senior Choir Leader.

She earned a BA (Hons) in Business Administration from Esoft Metropolitan University, and then the world became her playground.

Before long, modelling and pageantry also came into her scene.

She says she took to part-time modelling, as a hobby, and that led to pageants, grabbing 2nd Runner-up titles at Miss Nature Queen and Miss World Sri Lanka 2025.

When she’s not ruling the stage, or pool, Hansana’s belting tunes with Soul Sounds, Sri Lanka’s largest female ensemble.

What’s more, her artistry extends to drawing, and she loves hitting the open road for long drives, she says.

This water warrior is also on a mission – as Founder of Wave of Safety,

Hansana happens to be the youngest Executive Committee Member of the Sri Lanka Aquatic Sports Union (SLASU) and, as founder of Wave of Safety, she’s spreading water safety awareness and saving lives.

Today is Hansana’s ninth day in Egypt and the itinerary for today, says National Director for Sri Lanka, Brian Kerkoven, is ‘Jeep Safari and Sunset at the Desert.’

And … the all-important day at Miss Intercontinental 2025 is next Thursday, 29th January.

Well, good luck to Hansana.

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka