Features

STUDIES, EXAMS, STRIKES & TERRORISM IN THE UK

CONFESSIONS OF A GLOBAL GYPSY

By Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

Founder & Administrator – Global Hospitality Forum

chandij@sympatico.ca

Study Strategies

“Read these eight books on Hotel Management Accounting and Corporate Finance, cover to cover.” Professor Richard Kotas gave this direction to the graduate students in the M.Sc. program in International Hotel Management, at the University of Surrey (UoS), in the United Kingdom (UK). After the 1983 autumn semester mid-term tests, other professors followed suit with similar directions for their courses in Marketing Principles for Hotel Management, International Hotel Management Seminars, Quantitative Methods, Project Design and Analysis, Computer Applications, Organization Theory and Manpower Management etc. It was overwhelming! I quickly realised that I needed to develop a practical and effective strategy for my studies.

Some of my younger batchmates who were yet to gain any management experience, followed “reading cover to cover” directions literally. To me it did not sound doable. One marketing text book had over 700 pages! As none of my batch mates worked part-time, like I did, they all had more time for studies than I. So I settled for reading only the chapter summaries and figures and tables within book chapters.In order to acquire other shortcuts, I attended some non-mandatory ‘student success strategy’ sessions. These sessions provided some excellent study and exam strategies but were not well-attended. I immediately implemented the strategies I liked. Most of them worked well for me.

Exam Strategies

I spent a considerable amount of time at the university library analysing all old exam papers for some general courses in M.Sc. in Tourism Planning and Development, set by the same professors. I identified questions they repeated every year, in alternate years and occasionally. Based on that research, I guessed what questions could be included in the exams that I would sit.

After that I organized a M.Sc. study group of four like-minded students and assigned the most likely four questions, based on one question per graduate student basis. Each of us then became the expert on one question area per course. As the next step, we presented the answers developed by each expert, to each other. Then we debated and fine-tuned the four answers, which all four shared.

For our challenging courses such as Quantitative Methods, we made an appointment to meet each professor for a discussion. “Dr. Wanhill, the four of us are very nervous about your exam. We studied a lot and prepared some model answers to potential questions, but we still are not sure if we have done this well enough”, I told the senior lecturer who was teaching us Quantitative Methods.

Dr. Wanhill, a nice gentleman, was so impressed with our efforts that he said, “Come on chaps, don’t be nervous. Let’s go through all of your questions and answers.” He spent two hours coaching us and we guessed that the questions he spent more time in explaining were ‘sure exam questions’. This strategy helped us and four of us did well in the Quantitative Methods exams. It had been our worst course!

Implementing a tip from a ‘student success strategy’ session, I also spent time with each professor, prior to the final exam, inquiring what would be an ideal format for answering their questions at the exam. Some preferred essay type, a few liked point-form, and only one liked the idea of examples from my own career. I wrote the exams exactly the way they preferred, changing my style of answering to suit each professor. Applying my concept of ‘Personality Analysis’ and adjusting the way I communicated with each professor, proved to be beneficial.

I also learnt to invest about 30 minutes planning my answers at the beginning of each paper. I then planned to keep the last 30 minutes to review my four answers and fine-tune those before handing over my exam answer script at the last minute. With this strategy, I spent exactly 30-minutes per answer. To me, the answer plan and the time management were key elements for exam success.

After some debates about the effectiveness of ‘last minute studying’ prior to exams, I opted to adopt a concept of being at each day’s exam, right at the peak of my day. For this strategy, we first identified the number of hours each student can work without being tired. Most students were eight-hour people and a few were ten or twelve-hour people. Considering my multi-tasking work pattern in the previous years, I identified myself as a sixteen-hour person, which was rare. This meant that when the middle of an exam time was 10:00 am, I commenced my final revision studies on the same day of the exam, eight hours before that – at 2:00 am. As, at that time, I needed a maximum six hours of sleep to function well, I went to bed at 8:00 pm. This worked well for me.

When I sat one exam invigilated by Professor Richard Kotas, I could not believe my eyes. All four questions that my study group predicted were there. I had studied thoroughly the four model answers during the previous six hours since 2:00 am. “Chandi, why are you seated smiling, without answering the questions?” a baffled Professor Kotas asked me. “Sir, I am just planning my answers to these very difficult and unpredictable questions” I told him while trying to look worried. Although exam positions were not publicly announced, Professor Kotas indicated to me privately that I was overall first in both autumn and winter semester exams, something I had never achieved in my life prior to that.

Fight for Dissertation Topic

By early 1984, we began identifying topics for our dissertations, which had to be done ideally within a minimum of six months by students who had passed 10 exams over two semesters. Nine professors were assigned to supervise the nine students who were in my M.Sc. batch. When we commenced our one-on-one meetings with potential dissertation supervisors, we felt some pressure to align student dissertation topics with supervisors’ current research interests and publications.

The Head of the Department of the Hotel, Catering and Tourism Management at UoS at that time was Professor Brian Archer. He was an economist and an expert on tourism forecasting. “Ah, Chandi, I would like to suggest a dissertation topic ideal for someone like you. How about ‘Long-term tourism forecasting of South Asia?’ You can test exciting models, including mine, and even develop a new model!”, he suggested with a big and convincing smile. I simply hated that topic and had no interest in it.

I preferred to do research on a topic that would help the next stage of my career. After completing the M.Sc. program, I wanted to become the Food & Beverage Manager of a large, international five-star hotel. “I am thinking of something like, ‘Food and beverage management of British five-star hotels’ I announced to the dissatisfaction of Professor Archer. “That does not sound academically suitable for a master’s degree dissertation”, he said. I disagreed. When the university realized that I was determined to research and write on a practical subject, I was asked to make a convincing proposal to justify the suitability of my topic.

Although Professor Archer was disappointed with me on that occasion, he later became a good friend of mine. When I was the General Manager of the Lodge and the Village, Habarana, he stayed with me. He was a good chess player, and we played several games there. In later years, when he heard that I wish to do a Ph.D., he arranged an interview for me to be considered for a post of Lecturer at UoS, during my Ph.D. research. Unfortunately, as another professor in the selection committee did not support me with the same enthusiasm as Professor Archer, I did not get that job, but I re-joined UoS to do a M.Phil./Ph.D. in 1990.

After more negotiations in 1984, and revisions to my M.Sc. dissertation proposal, eventually, UoS approved a slightly modified topic for my research – ‘Food and beverage operations in the context of five-star London hotels’. Professor Richard Kotas became my dissertation supervisor. “Chandi, covering the whole of UK will be too much. Just focus on the 16 five-star hotels in London”, he suggested. I agreed and said that, “I will work or observe in all of these 16 hotels and interview the relevant managers. Kindly give me letters of introduction.” “Chandi, in addition, as the first step, you must read all books – cover to cover, and journal articles ever written in English about Food and beverage management and operations”, he suggested. I said, “Yes, Sir!” and did exactly that over a period of three months.

British Strikes

UK had strong unions and a culture of strikes. Some strikes affected me personally. One I remember clearly was towards the end of March in 1984, when the transport workers paralyzed London’s buses and subways. That strike was the first of a series of work stoppages in major British cities to protest Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher’s proposals for local government changes. Cars and cyclists jammed roads in London as some 2.5 million people found alternate ways to work. Thousands walked while others jogged or hitch-hiked. My wife and I stayed at home without going to work.

On March 6, 1984, when I saw on the BBC TV news about a miners’ strike, I assumed that it was one of those strikes in UK which would last for a short period of time before a settlement. I was wrong. It was a major, industrial action within the British coal industry in an attempt to prevent colliery closures, suggested by the government for economic reasons. The strike was led by Arthur Scargill, the President of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) against the National Coal Board (NCB), a government agency. Opposition to the strike was led by the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher that wanted to reduce the power of the trade unions. This strike lasted a year, and I eagerly waited to watch the TV news about it every evening until the strike finally ended in March, 1985.

Violent confrontations between flying pickets and police characterised the year-long strike which ended in a decisive victory for the Conservative government and allowed the closure of most of Britain’s collieries.

Many observers regarded this landmark strike as the most bitter industrial dispute in British history. The number of person-days of work lost to the strike was over 26 million, making it one of the biggest strikes in history. Thousands were arrested and charged, over a 100 were injured, and sadly, six lost their lives.

From that historic moment onwards, British unions were somewhat weakened. With the tough handling of the NUM strike, Margaret Thatcher consolidated her reputation as the ‘Iron Lady’, a nickname that became associated with her uncompromising politics and the tough leadership style. As the first female prime minister of UK, she implemented policies that became known as ‘Thatcherism’.

I spent the summer of 1979 in London soon after Margaret Thatcher became the Prime Minister of UK. On April 12, 1984, I served her dinner at a royal banquet held in honour of the Queen of England at the Dorchester. When she was ousted from the position of the Prime Minister after a cabinet revolt in 1990, I was living in London again. On November 28, 1990, I watched her final speech as the Prime Minister in the House of Commons, and leaving her office and residence in Downing Street in tears. A few years after that, I hosted her successor, John Major in my office at Le Meridien Jamaica Pegasus Hotel.

Terrorism

The civil war in Sri Lanka which commenced in July 1983 before we left for UK was getting worse. Although we thought that UK was peaceful, that country had its large share of terrorism, predominately in the hands of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). During my first stay in UK in 1979, I was shocked to see on TV that IRA claimed responsibility for the assassination of Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. As the supreme allied commander for Southeast Asia, he had commanded the British troops from his base in Ceylon during the latter part of World War II.

My first direct exposure to terrorism in UK was when I was working at Bombay Brasserie in Kensington, London. “Chandi, be careful, when going home today. Avoid the circle line and don’t go near Knightsbridge. IRA bombed Harrods!”, an Indian work colleague warned me. Harrods, world famous upmarket department store in the affluent Knightsbridge district, near Buckingham Palace, had been subject to two IRA bomb attacks earlier. Although the IRA had sent a warning 37 minutes before a car bomb that exploded outside Harrods on December 17, 1983, the area had not been evacuated. Due to this car bomb, six people died and 90 were injured. This was the 40th terrorist attack in UK since early 1970s.

On October 12, 1984, a powerful IRA bomb went off with deadly effect in the Grand Hotel in Brighton, England, where members of Britain’s Conservative Party were gathered for a party conference. IRA’s target was to assassinate the British Prime Minister and the other key members of her government. The bomb ripped a hole through several storeys of the 120-year-old hotel.

When the bomb went off just before 3:00 am, Margaret Thatcher was still awake at the time, working in her suite on her conference speech for the next day. The blast badly damaged her suite’s bathroom, but left its sitting room and bedroom untouched. She and her husband were fortunate to escape serious injury, although 34 people were injured and another five killed. The next day, when we watched her on TV delivering an excellent party conference speech with a brave face, I remarked to my wife, “She truly is a real Iron Lady!”

On October 31, 1984 when I was going to work at the Dorchester, I heard a loud celebration in some parts of London. Some Sikh men were lighting fire crackers while celebrating and distributing sweets and fruits to onlookers. I assumed that it must be a Sikh holiday event, but soon realised that they were celebrating an assassination. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had been assassinated at her residence in New Delhi, early morning that day, by her Sikh bodyguards.

I knew that five months prior to that day, Indira Gandhi had ordered the removal of a prominent orthodox Sikh religious leader and his rebel followers from the Golden Temple of Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar, Punjab. The collateral damage included the death of approximately 500 Sikh pilgrims. The military action on the sacred temple was criticized both inside and outside India. Indira Gandhi’s assassination sparked four days of riots that left more than 8,000 Indian Sikhs dead in revenge attacks. The world is a dangerous place to live in.

Features

Wishes, Resolutions and Climate Change

Exchanging greetings and resolving to do something positive in the coming year certainly create an uplifting atmosphere. Unfortunately, their effects wear off within the first couple of weeks, and most of the resolutions are forgotten for good. However, this time around, we must be different, because the nation is coming out of the most devastating natural disaster ever faced, the results of which will impact everyone for many years to come. Let us wish that we as a nation will have the courage and wisdom to resolve to do the right things that will make a difference in our lives now and prepare for the future. The truth is that future is going to be challenging for tropical islands like ours.

We must not have any doubts about global warming phenomenon and its impact on local weather patterns. Over its 4.5-billion-year history, the earth has experienced drastic climate changes, but it has settled into a somewhat moderate condition characterised by periods of glaciation and retreat over the last million years. Note that anatomically modern Homo sapiens have been around only for two to three hundred thousand years, and it is reasoned that this stable climate may have helped their civilisation. There have been five glaciation periods over the last five hundred thousand years, and these roughly hundred-thousand-year cycles are explained by the astronomical phenomenon known as the Milankovitch Cycle (the lows marked with stars in Figure 1). At present, the earth is in an inter glacial period and the next glaciation period will be in about eighty thousand years.

(See Figure 1. Glaciation Cycles)

(See Figure 1. Glaciation Cycles)

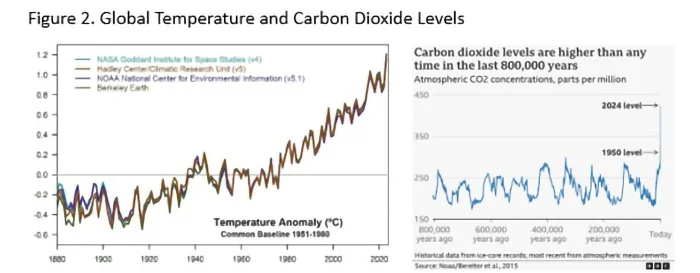

During these cycles, the global mean temperature has changed by about 7-8 degrees Centigrade. In contrast to this natural variation, earth has been experiencing a rapid temperature increase over the past hundred years. There is ample scientific evidence from multiple sources that this is caused by the increase in carbon dioxide gas in the atmosphere, which has seen a 50% increase over the historical levels in just hundred years (Figure 2). Carbon dioxide is one of the greenhouse gases which traps heat from the sun and slows the natural cooling process of the earth. This increase of carbon dioxide is due to human activities: fossil fuel burning, industrial processes, deforestation, and agricultural practices. Ironically, those who suffer from the consequences did not contribute to these changes; those who did contribute are trying their best to convince the world that the temperature changes we see are natural, and nothing should be done. We must have no illusions that global warming is a human-caused phenomenon, and it has serious repercussions.

(See Figure 2. Global Temperature and Carbon Dioxide Levels)

Why should we care about global warming? Well, there are many reasons, but let us focus on earth’s water cycle. Middle schoolers know that water evaporates from the oceans, rises into the atmosphere where it cools, condenses, and falls back onto earth as rain or snow. When the oceans warm, the evaporation increases, and the warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour. Water laden atmosphere results in severe and erratic weather. Ironically, water vapour is also a greenhouse gas, and this has a snowballing effect. The increased ocean temperature also disrupts ocean currents that influence the weather on land. The combined result is extreme and severe weather: violent storms and droughts depending on the geographic location. What is happening on the West coast of the USA is an example. The net result will be major departures from what is considered normal weather over millennia.

International organisations have been talking for 30 years about limiting global temperature increase to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels by curtailing greenhouse gas emissions. But not much has been done and the temperature has risen by 1.2oC already. The challenge is that even if we can stop greenhouse gas emissions completely, right now, we have the problem of removing already existing 2,500 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere, for which there are no practical solutions yet. Scientists worry about the consequences of runaway temperature increase and its effect on human life, which are many. It is not a doomsday prediction of life disappearing from earth, but a warning that life will be quite different from what humans are used to. All small tropical nations like ours are burdened with mitigating the consequences; in other words, get ready for more Ditwahs, do not wait for the twelve-day forecast.

Some opined that not enough warning was given regarding Ditwah; the truth is that the tools available for long-term prediction of the path or severity of a weather event (cyclone, typhoon, hurricane, tornado) are not perfect. There are multitude of rapidly changing factors contributing to the behavior of weather events. Meteorologists feed most up to date data to different computer models and try to identify the prediction with the highest probability. The multiple predictions for the same weather event are represented by what is known as spaghetti plots. Figure 3 shows the forecasted paths of a 2019 Atlantic hurricane five days ahead on the right and the actual path it followed on the left. While the long-term prediction of the path of a cyclone remains less accurate, its strength can vary within hours. There are several Indian ocean cyclones tracking sites online accessible to the public.

Figure 3. Forecasting vs Reality

There is no argument that short-term forecasts of this nature are valuable in saving lives and movable assets, but having long term plans in place to mitigate the effects of natural disasters is much more important than that. If a sizable section of the population must start over their lives from ground zero after every storm, how can a country economically develop?

The degree of our unpreparedness came to light during Ditwah disaster. It is not for lack of awareness; judging by the deluge of newspaper articles, blogs, vlogs, and speeches made, there is no shortage of knowledge and technical expertise to meet the challenge. The government has assured the necessary resources, and there is good reason to trust that the funds will be spent properly and not to line the pockets as happened during previous disasters. However, history tells us that despite the right conditions and good intentions, we could miss the opportunity again. Reasons for such skepticisms emerged during the few meetings the President held with the bureaucrats while visiting effected areas. Also, the COPE committee meetings plainly display the inherent inefficiencies and irregularities of our system and the absence of work ethics among all levels of the bureaucracy.

What it tells us is that we as a nation have an attitude problem. There are ample scholarly analyses by local as well as international researchers on this aspect of Sri Lankan psyche, and they label it as either island or colonial mentality. The first refers to the notion of isolated communities perceiving themselves as exceptional or superior to the rest of the world, and that the world is hell-bent on destroying or acquiring what they have. This attitude is exacerbated by the colonial mentality that promoted the divide and conquer rules and applied it to every societal characteristic imaginable; and plundered natural resources. As a result, now we are divided along ethnic, linguistic, religious, political, class, caste, geography, wealth, and many more real and imagined lines. Sadly, politicians, some religious leaders, and other opportunists keep inflaming these sentiments for their benefit when most of the population is willing to move on.

The first wish, therefore, is to get the strength, courage, and wisdom to think rationally, and discard outdated and outmoded belief systems that hinder our progress as a nation. May we get the courage to stop venerating elite who got there by exploiting the masses and the country’s wealth. More importantly, may we get the wisdom to educate the next generation to be free thinkers, give them the power and freedom to reject fabrications, myths, and beliefs that are not based on objective facts.

This necessitates altering our attitude towards many aspects of life. There is no doubt that free thinking does not come easily, it involves the proverbial ‘exterminating the consecrated bull.’ We are rightfully proud about our resplendent past. It is true that hydraulic engineering, art, and architecture flourished during the Anuradhapura period.

However, for one reason or another, we have lost those skills. Nowadays, all irrigation projects are done with foreign aid and assistance. The numerous replicas of the Avukana statue made with the help of modern technology, for example, cannot hold a candle to the real one. The fabled flying machine of Ravana is a figment of marvelous imagination of a skilled poet. Reality is that today we are a nation struggling with both natural and human-caused disasters, and dependent on the generosity of other nations, especially our gracious neighbor. Past glory is of little help in solving today’s problems.

Next comes national unity. Our society is so fragmented that no matter how beneficial a policy or an idea for the nation could be, some factions will oppose it, not based on facts, but by giving into propaganda created for selfish purposes. The island mentality is so pervasive, we fail to trust and respect fellow citizens, not to mention the government. The result is absence of long-term planning and stability. May we get the insight to separate policy from politics; to put nation first instead of our own little clan, or personal gains.

With increasing population and decreasing livable and arable land area, a national land management system becomes crucial. We must have an intelligent zoning system to prevent uncontrolled development. Should we allow building along waterways, on wetlands, and road easements? Should we not put the burden of risk on the risk takers using an insurance system instead of perpetual public aid programs? We have lost over 95% of the forest cover we had before European occupation. Forests function as water reservoirs that release rainwater gradually while reducing soil erosion and stabilizing land, unlike monocultures covering the hill country, the catchments of many rivers. Should we continue to allow uncontrolled encroachment of forests for tourism, religious, or industrial purposes, not to mention personal enjoyment of the elite? Is our use of land for agricultural purposes in keeping with changing global markets and local labor demands? Is haphazard subsistence farming viable? What would be the impact of sea level rising on waterways in low lying areas?

These are only a few aspects that future generations will have to grapple with in mitigating the consequences of worsening climate conditions. We cannot ignore the fact that weather patterns will be erratic and severe, and that will be the new normal. Survival under such conditions involves rational thinking, objective fact based planning, and systematic execution with long term nation interests in mind. That cannot be achieved with hanging onto outdated and outmoded beliefs, rituals, and traditions. Weather changes are not caused by divine interventions or planetary alignments as claimed by astrologers. Let us resolve to lay the foundation for bringing up the next generation that is capable of rational thinking and be different from their predecessors, in a better way.

by Geewananda Gunawardana

Features

From Diyabariya to Duberria: Lanka’s Forgotten Footprint in Global Science

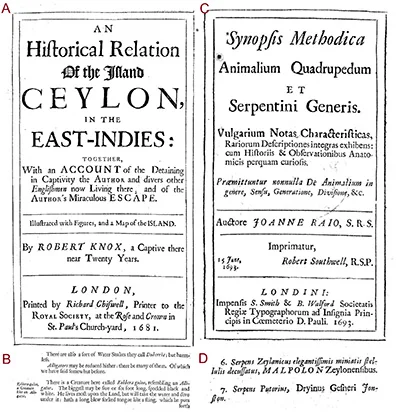

For centuries, Sri Lanka’s biological knowledge travelled the world — anonymously. Embedded deep within the pages of European natural history books, Sinhala words were copied, distorted and repurposed, eventually fossilising into Latinised scientific names of snakes, bats and crops found thousands of kilometres away.

Africa’s reptiles, Europe’s taxonomic catalogues and global field guides still carry those echoes, largely unnoticed and uncredited.

Now, a Sri Lankan herpetologist is tracing those forgotten linguistic footprints back to their source.

Through painstaking archival research into 17th- and 18th-century zoological texts, herpetologist and taxonomic researcher Sanjaya Bandara has uncovered compelling evidence that several globally recognised scientific names — long assumed to be derived from Greek or Latin — are in fact rooted in Sinhala vernacular terms used by villagers, farmers and hunters in pre-colonial Sri Lanka.

“Scientific names are not just labels. They are stories,” Bandara told The Island. “And in many cases, those stories begin right here in Sri Lanka.”

Sanjaya Bandara

At the heart of Bandara’s work is etymology — the study of word origins — a field that plays a crucial role in zoology and taxonomy.

While classical languages dominate scientific nomenclature, his findings reveal that Sinhala words were quietly embedded in the foundations of modern biological classification as early as the 1700s.

One of the most striking examples is Ahaetulla, the genus name for Asian vine snakes. “The word Ahaetulla is not Greek or Latin at all,” Bandara explained. “It comes directly from the Sinhala vernacular used by locals for the Green Vine Snake.” Remarkably, the term was adopted by Carl Linnaeus himself, the father of modern taxonomy.

Another example lies in the vespertilionid bat genus Kerivoula, described by British zoologist John Edward Gray. Bandara notes that the name is a combination of the Sinhala words kiri (milky) and voula (bat). Even the scientific name of finger millet, Eleusine coracana, carries linguistic traces of the Sinhala word kurakkan, a cereal cultivated in Sri Lanka for centuries.

Yet Bandara’s most intriguing discoveries extend far beyond the island — all the way to Africa and the Mediterranean.

In a research paper recently published in the journal Bionomina, Bandara presented evidence that two well-known snake genera, Duberria and Malpolon, both described in 1826 by Austrian zoologist Leopold Fitzinger, likely originated from Sinhala words.

The name Duberria first appeared in Robert Knox’s 1681 account of Ceylon, where Knox refers to harmless water snakes called “Duberria” by locals. According to Bandara, this was a mispronunciation of Diyabariya, the Sinhala term for water snakes.

“Mispronunciations are common in Knox’s writings,” Bandara said. “English authors of the time struggled with Sinhala phonetics, and distorted versions of local names entered European literature.”

Over time, these distortions became formalised. Today, Duberria refers to African slug-eating snakes — a genus geographically distant, yet linguistically tethered to Sri Lanka.

Bandara’s study also proposes the long-overdue designation of a type species for the genus, reviving a 222-year-old scientific name in the process.

Equally compelling is the case of Malpolon, the genus of Montpellier snakes found across North Africa, the Middle East and southern Europe. Bandara traced the word back to a 1693 work by English zoologist John Ray, which catalogued snakes from Dutch India — including Sri Lanka.

“The term Malpolon appears alongside Sinhala vernacular names,” Bandara noted. “It is highly likely derived from Mal Polonga, meaning ‘flowery viper’.” Even today, some Sri Lankan communities use Mal Polonga to describe patterned snakes such as the Russell’s Wolf Snake.

Bandara’s research further reveals Sinhala roots in the African Red-lipped Herald Snake (Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia), whose species name likely stems from Hothambaya, a regional Sinhala term for mongooses and palm civets.

“These findings collectively show that Sri Lanka was not just a source of specimens, but a source of knowledge,” Bandara said. “Early European naturalists relied heavily on local names, local guides and local ecological understanding.”

Perhaps the most frequently asked question Bandara encounters concerns the mighty Anaconda. While not a scientific name, the word itself is widely believed to be a corruption of the Sinhala Henakandaya, another snake name recorded in Ray’s listings of Sri Lankan reptiles.

Perhaps the most frequently asked question Bandara encounters concerns the mighty Anaconda. While not a scientific name, the word itself is widely believed to be a corruption of the Sinhala Henakandaya, another snake name recorded in Ray’s listings of Sri Lankan reptiles.

“What is remarkable,” Bandara reflected, “is that these words travelled across continents, entered global usage, and remained there — often stripped of their original meanings.”

For Bandara, restoring those meanings is about more than taxonomy. It is about reclaiming Sri Lanka’s rightful place in the history of science.

“With this study, three more Sinhala words formally join scientific nomenclature,” he said.

“Who would have imagined that a Sinhala word would be used to name a snake in Africa?”

Long before biodiversity hotspots became buzzwords and conservation turned global, Sri Lanka’s language was already speaking through science — quietly, persistently, and across continents.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Children first – even after a disaster

However, the children and their needs may be forgotten after a disaster.

Do not forget that children will also experience fear and distress although they may not have the capacity to express their emotions verbally. It is essential to create child-friendly spaces that allow them to cope through play, draw, and engage in supportive activities that help them process their experiences in a healthy manner.

The Institute for Research & Development in Health & Social Care (IRD), Sri Lanka launched the campaign, titled “Children first,” after the 2004 Tsunami, based on the fundamental principle of not to medicalise the distress but help to normalise it.

The Island picture page

The IRD distributed drawing material and play material to children in makeshift shelters. Some children grabbed drawing material, but some took away play material. Those who choose drawing material, drew in different camps, remarkably similar pictures; “how the tidal wave came”.

“The Island” supported the campaign generously, realising the potential impact of it.

The campaign became a popular and effective public health intervention.

“A public health intervention (PHI) is any action, policy, or programme designed to improve health outcomes at the population level. These interventions focus on preventing disease, promoting health, and protecting communities from health threats. Unlike individual healthcare interventions (treating individuals), which target personal health issues, public health interventions address collective health challenges and aim to create healthier environments for all.”

The campaign attracted highest attention of state and politicians.

The IRD continued this intervention throughout the protracted war, and during COVID-19.

The IRD quick to relaunch the “children first” campaign which once again have received proper attention by the public.

While promoting a public health approach to handling the situation, we would also like to note that there will be a significant smaller percentage of children and adolescents will develop mental health disorders or a psychiatric diagnosis.

We would like to share the scientific evidence for that, revealed through; the islandwide school survey carried out by the IRD in 2007.

During the survey, it was found that the prevalence of emotional disorder was 2.7%, conduct disorder 5.8%, hyperactivity disorder was 0.6%, and 8.5% were identified as having other psychiatric disorders. Absenteeism was present in 26.8%. Overall, previous exposure to was significantly associated with absenteeism whereas exposure to conflict was not, although some specific conflict-related exposures were significant risk factors. Mental disorder was strongly associated with absenteeism but did not account for its association with tsunami or conflict exposure.

During the survey, it was found that the prevalence of emotional disorder was 2.7%, conduct disorder 5.8%, hyperactivity disorder was 0.6%, and 8.5% were identified as having other psychiatric disorders. Absenteeism was present in 26.8%. Overall, previous exposure to was significantly associated with absenteeism whereas exposure to conflict was not, although some specific conflict-related exposures were significant risk factors. Mental disorder was strongly associated with absenteeism but did not account for its association with tsunami or conflict exposure.

The authors concluded that exposure to traumatic events may have a detrimental effect on subsequent school attendance. This may give rise to perpetuating socioeconomic inequality and needs further research to inform policy and intervention.

Even though, this small but significant percentage of children with psychiatric disorders will need specialist interventions, psychological treatment more than medication. Some of these children may complain of abdominal pain and headaches or other physical symptoms for which doctors will not be able to find a diagnosable medical cause. They are called “medically unexplained symptoms” or “somatization” or “bodily distress disorder”.

Sri Lanka has only a handful of specialists in child and adolescent psychiatric disorders but have adult psychiatrists who have enough experience in supervising care for such needy children. Compared to tsunami, the numbers have gone higher from around 20 to over 100 psychiatrists.

Most importantly, children absent from schools will need more close attention by the education authorities.

In conclusion, going by the principles of research dissemination sciences, it is extremely important that the public, including teachers and others providing social care, should be aware that the impact of Cyclone Ditwah, which was followed by major floods and landslides, which is a complex emergency impact, will range from normal human emotional behavioural responses to psychiatric illnesses. We should be careful not to medicalise this normal distress.

It’s crucial to recall an important statement made by the World Health Organisation following the Tsunam

Prof. Sumapthipala MBBS, DFM, MD Family Medicine, FSLCFP (SL), FRCPsych, CCST (UK), PhD (Lon)]

Director, Institute for Research and Development in Health and Social Care, Sri Lanka

Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Keele University, UK

Emeritus Professor of Global Mental Health, Kings College London

Secretary General, International society for Twin Studies

Visiting Professor in Psychiatry and Biomedical Research at the Faculty of Medicine, Kotelawala Defence University, Sri Lanka

Associate Editor, British Journal Psychiatry

Co-editor Ceylon Medical Journal.

Prof. Athula Sumathipala

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoGeneral education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoSuspension of Indian drug part of cover-up by NMRA: Academy of Health Professionals

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoChief selector’s remarks disappointing says Mickey Arthur

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoA very sad day for the rule of law

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoUS Ambassador to Sri Lanka among 29 career diplomats recalled