Features

SRI LANKA’S KILLING FIELD

UNP’s Defeat-II

By Jayantha Somasundaram

“I survived once but he will finally get me killed. He will get Gamini Dissanayake killed. Then I am sure he himself will get killed.” Lalith Athulathmudali (The Print 27/12/17)

———————-

Though his ascent to the Presidency was heavily thwarted by the Govigama elite that created the UNP, Premadasa succeeded to the office in January 1989.

—————-

Even after he became President, the UNP’s Govigama establishment kept up a latent but relentless campaign to undermine Ranasinghe Premadasa. In August 1991 Gamini Dissanayake and Lalith Athulathmudali succeeded in surreptitiously getting the support of the opposition to present a motion in parliament to impeach the President, accusing him of everything from treason to corruption. It contained 123 signatures, including 47 of the 121 UNP MPs.

“As Premadasa walked into Parliament he was fiercely heckled by MPs. The President’s security men were concerned enough to have a helicopter on standby, in case the assaults turned from verbal to physical.” (Time 7 Oct 1991) Premadasa was able to get a sufficient number of UNP MPs to confess that they did not know what they had signed and narrowly avoided impeachment. Political Scientist Professor Jayadeva Uyangoda explained, “The attempt to impeach Premadasa can be seen as a backlash from the ruling stratum in Colombo that cut across the old guard of the UNP as well as the SLFP. They saw Premadasa as a usurper.”

“The two leaders of the impeachment were both drawn from the anglicised elite in Colombo. Premadasa put down the revolt by getting an acquiescent speaker of parliament (M. H. Mohamed) to deny the impeachment motion, but it fed his lifelong bitterness about caste discrimination.” (Far Eastern Economic Review 13/5/93) Athulathmudali and Dissanayake represented that elite, educated at Royal and Oxford, Trinity and Cambridge respectively, they commanded the loyalty of the Sinhala establishment who saw them as the natural leaders. They and their supporters were now expelled from the UNP. Lakshman Perera, one of Athulathmudali’s supporters, a municipal councillor who had authored a controversial play about Premadasa, Me kawda? Monawada karane? (Who is this? What is he doing?) disappeared. “The political rivalry between Premadasa and Athulathmudali led to a media war between the state-owned TV, radio and newspapers and the opposition-owned press. UNP thugs openly attacked journalists who covered opposition rallies.” (Asiaweek 12/5/93)

Premadasa had been trying to get the point across that he would not take kindly to schemes to unseat him, or media attempts to criticise him. “Scores of UNP goons, armed with bicycle chains, clubs, swords and small firearms, descended on a group of journalists covering a leaflet distribution campaign conducted by UNP dissidents Lalith and Gamini opposite the Fort Railway Station. Cameras were smashed and journalists beaten up mercilessly. When the victims tried to lodge a complaint with the Fort police the then OIC stood, blocking the entrance to the police station and declaring that it was closed for the day!” (Editorial The Island 25/5/16)

“One of Sri Lanka’s top cartoonists, Jiffrey Yunoos was stabbed and his home and vehicle were wrecked … Athulathmudali was fired on twice … his supporters were assaulted with iron bars and cricket stumps … The last year witnessed the destruction by police of an anti-government printing press, a grenade attack on a meeting of dissident members of the ruling party, death threats against human rights lawyers and assaults on opposition politicians,” reported Janes Foreign Report (24/9/92)

Richard de Zoysa

Richard de Zoysa epitomised the elite. He was the grandson of Manickasothy Saravanamuttu and Francis de Zoysa, belonging therefore to two of Colombo’s best-known families. “On the night of February 18th 1990 Ronnie Gunasinghe, Senior Superintendent of Police and a confidant of Premadasa, was having drinks with Deputy Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne. At one point says a senior police officer, Wijeratne called Premadasa and told him of a plan to pick up the journalist. The next day de Zoysa’s tortured body was found floating off a beach south of Colombo. Wijeratne was killed in a car bomb explosion in March 1991. Gunasinghe died with Premadasa.” (Asiaweek 12/5/93)

Sri Lanka had now become a political killing field.

Richard de Zoysa was involved in Psychological operations (PSYOP) and propaganda for the Army when Lalith Athulathmudali was Minister of National Security. His abduction occurred when Athulathmudali was out of Colombo and could not be contacted.

According to human rights lawyer Basil Fernando “when the abduction and disappearance became a scandal the government began a campaign to ridicule the personality of Richard de Zoysa.” (Sri Lanka Guardian 13/4/10) “Another was that RAW (Indian Intelligence) was the culprit; this idea was put forward by Premadasa’s man, (Information Minister) A. J. Ranasinghe.” (Sunday Observer 26/3/17)

“You keep referring to abduction and murder. What if it is not murder, but suicide or something else?” asked Ranil Wickeremesinghe, a government minister. ‘What I hate these people for is their lies,’” says (Richard’s mother) Manorani Saravanamuttu (The Washington Post 3/3/91).

“I see no reason to disbelieve Manorani’s claim that a week after Richard’s death Ranjan Wijeratne held a party at the BMICH and told the death squads that he would ensure immunity for anything that happened previously.” (The Island 25/3/01)

Denzil Kobbekaduwa

The UNP had always seen Lieutenant General Denzil Kobbekaduwa as a political threat. While still a young officer he had been sent on compulsory leave both in 1967 and again in 1977 by the Senanayake and Jayewardena Regimes. Educated at Trinity and Sandhurst, he had assumed command of the Northern Theatre and his strategy for overcoming the LTTE was meeting with success. This made him immensely popular not only with the armed forces but also among Sinhalese looking for a military hero who would lead them to victory in the Civil War. As a kinsman of Mrs Bandaranaike he was seen as a possible presidential candidate. “In June 1992 Brig Chula Seneviratne, who was in Military Intelligence was summoned one night by Gen Kobbekaduwa (who) told him of a threat to his life from within the Army.” (Daily News 2/5/98)

Kobbekaduwa was killed in Kayts in August 1992. A hundred thousand attended his funeral, they were chanting slogans and attacking government supporters injuring among others Minister A J Ranasinghe and Deputy Minister John Amaratunga. Riot Police had to fire tear gas to quell the protesters.

Mrs Kobbekaduwa called for an international commission to investigate her husband’s death. After the UNP had lost power an independent commission was established revealing that “from January 1990 Gen Kobbekaduwa, Lalith Athulathmudali and Gamini Dissanayake were investigating the secret delivery of weapons, arms and ammunition (to the LTTE by Premadasa and) … wanted to place all this before an international tribunal.” The Commission would determine that “the explosion was in the vehicle” in which Kobbekaduwa travelled and that it was able “to come to one conclusion only that President Premadasa targeted Maj Gen Kobbekaduwa for assassination.” (Daily News 11/3/98)

With Kobbekaduwa’s death Premadasa’s opposition came into the open. Gamini Dissanayake commissioned an investigation into the blast that killed Kobbekaduwa and brought in international experts. He and Athulathmudali formed their own party, the Democratic United National Front. “Within months it had more than 500,000 members. They held rally after rally denouncing the President to crowds of 50,000 or more. They were expected to win handsomely in the seven provincial elections to be held on May 17th 1993.” (Asiaweek 12/5/93)

Indian journalist Sekhar Gupta reported a conversation he had with Athulathmudali in June 1991. Pointing a finger at Premadasa, Athulathmudali had said: “I survived once but he will finally get me killed. He will get Gamini Dissanayake killed. Then I am sure he himself will get killed.” (The Print 27/12/17).

According to Colombo US Embassy staffer Daya Gamage, in August 1992 having finished her time in Colombo, the US Ambassador Marion Creekmore made a farewell call on Premadasa during which she warned “If any harm comes to one of them (Lalith and Gamini), the finger will be pointed at you.” (Asian Tribune) 5/1/18)

(To be continued)

Features

The hollow recovery: A stagnant industry – Part I

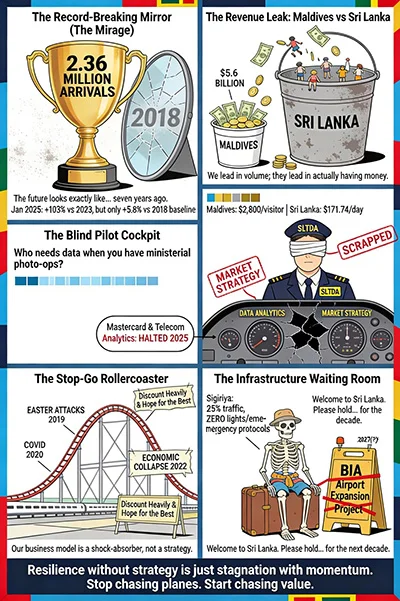

The headlines are seductive: 2.36 million tourists in 2025, a new “record.” Ministers queue for photo opportunities. SLTDA releases triumphant press statements. The narrative is simple: tourism is “back.”

The headlines are seductive: 2.36 million tourists in 2025, a new “record.” Ministers queue for photo opportunities. SLTDA releases triumphant press statements. The narrative is simple: tourism is “back.”

But scratch beneath the surface and what emerges is not a success story but a cautionary tale of an industry that has mistaken survival for transformation, volume for value, and resilience for strategy.

Problem Diagnosis: The Mirage of Recovery

Yes, Sri Lanka welcomed 2.36 million tourists in 2025, marginally above the 2.33 million recorded in 2018. This marks a full recovery from the consecutive disasters of the Easter attacks (2019), COVID-19 (2020-21), and the economic collapse (2022). The year-on-year growth looks impressive: 15.1% above 2024’s 2.05 million arrivals.

But context matters. Between 2018 and 2023, arrivals collapsed by 36.3%, bottoming out at 1.49 million. The subsequent “rebound” is simply a return to where we were seven years ago, before COVID, before the economic crisis, even before the Easter attacks. We have spent six years clawing back to 2018 levels while competitors have leaped ahead.

Consider the monthly data. In 2023, January arrivals were just 102,545, down 57% from January 2018’s 238,924. By January 2025, arrivals reached 252,761, a dramatic 103% jump over 2023, but only 5.8% above the 2018 baseline. This is not growth; it is recovery from an artificially depressed base. Every month in 2025 shows the same pattern: strong percentage gains over the crisis years, but marginal or negative movement compared to 2018.

The problem is not just the numbers, but the narrative wrapped around them. SLTDA’s “Year in Review 2025” celebrates the 15.6% first-half increase without once acknowledging that this merely restores pre-crisis levels. The “Growth Scenarios 2025” report projects arrivals between 2.4 and 3.0 million but offers no analysis of what kind of tourism is being targeted, what yield is expected, or how market composition will shift. This is volume-chasing for its own sake, dressed up as strategic planning.

Comparative Analysis: Three Decades of Standing Still

The stagnation becomes stark when placed against Sri Lanka’s closest island competitors. In the mid-1990s, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, started from roughly the same base, around 300,000 annual arrivals each. Three decades later:

Sri Lanka: From 302,000 arrivals (1996) to 2.36 million (2025), with $3.2 billion

Maldives: From 315,000 arrivals (1995) to 2.25 million (2025), with $5.6 billion

The raw numbers obscure the qualitative difference. The Maldives deliberately crafted a luxury, high-yield model: one-island-one-resort zoning, strict environmental controls, integrated resorts layered with sustainability credentials. Today, Maldivian tourism generates approximately $5.6 billion from 2 million tourists, an average of $2,800 per visitor. The sector represents 21% of GDP and generates nearly half of government revenue.

Sri Lanka, by contrast, has oscillated between slogans, “Wonder of Asia,” “So Sri Lanka”, without embedding them in coherent policy. We have no settled model, no consensus on what kind of tourism we want, and no institutional memory because personnel and priorities change with every government. So, we match or slightly exceed competitors in arrivals, but dramatically underperform in revenue, yield, and structural resilience.

Root Causes: Governance Deficit and Policy Failure

The stagnation is not accidental; it is manufactured by systemic governance failures that successive governments have refused to confront.

1. Policy Inconsistency as Institutional Culture

Sri Lanka has rewritten its Tourism Act and produced multiple master plans since 2005. The problem is not the absence of strategy documents but their systematic non-implementation. The National Tourism Policy approved in February 2024 acknowledges that “policies and directions have not addressed several critical issues in the sector” and that there was “no commonly agreed and accepted tourism policy direction among diverse stakeholders.”

This is remarkable candor, and a damning indictment. After 58 years of organised tourism development, we still lack policy consensus. Why? Because tourism policy is treated as political property, not national infrastructure. Changes in government trigger wholesale personnel changes at SLTDA, Tourism Ministry, and SLTPB. Institutional knowledge evaporates. Priorities shift with ministerial whims. Therefore, operators cannot plan, investors cannot commit, and the industry lurches from crisis response to crisis response without building structural resilience.

2. Fragmented Institutional Architecture

Tourism responsibilities are scattered across the Ministry of Tourism, Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB), provincial authorities, and an ever-expanding roster of ad hoc committees. The ADB’s 2024 Tourism Sector Diagnostics bluntly notes that “governance and public infrastructure development of tourism in Sri Lanka is fragmented and hampered.”

Tourism responsibilities are scattered across the Ministry of Tourism, Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB), provincial authorities, and an ever-expanding roster of ad hoc committees. The ADB’s 2024 Tourism Sector Diagnostics bluntly notes that “governance and public infrastructure development of tourism in Sri Lanka is fragmented and hampered.”

No single institution owns yield. No one is accountable for net foreign exchange contribution after leakages. Quality standards are unenforced. The tourism development fund, 1% of the tourism levy plus embarkation taxes, is theoretically allocated 70% to SLTPB for global promotion, but “lengthy procurement and approval processes” render it ineffective.

Critically, the current government has reportedly scrapped sophisticated data analytics programmes that were finally giving SLTDA visibility into spending patterns, high-yield segments, and tourist movement. According to industry reports in late 2025, partnerships with entities like Mastercard and telecom data analytics have been halted, forcing the sector to fly blind precisely when data-driven decision-making is essential.

3. Infrastructure Deficit and Resource Misallocation

The Bandaranaike International Airport Development Project, essential for handling projected tourist volumes, has been repeatedly delayed. Originally scheduled for completion years ago, it is now re-tendered for 2027 delivery after debt restructuring. Meanwhile, tourists in late 2025 faced severe congestion at BIA, with reports of near-miss flights due to immigration and check-in bottlenecks.

At cultural sites, basic facilities are inadequate. Sigiriya, which generates approximately 25% of cultural tourist traffic and charges $36 per visitor, lacks adequate lighting, safety measures, and emergency infrastructure. Tourism associations report instances of tourists being attacked by wild elephants with no effective safety protocols.

SLTDA Chairman statements acknowledge “many restrictions placed on incurring capital expenditure” and “embargoes placed not only on tourism but all Government institutions.” The frank admission: we lack funds to maintain the assets that generate revenue. This is governance failure in its purest form, allowing revenue-generating infrastructure to decay while chasing arrival targets.

The Stop-Go Trap: Volatility as Business Model

What truly differentiates Sri Lanka from competitors is not arrival levels but the pattern: extreme stop-go volatility driven by crisis and short-term stimulus rather than steady, strategic growth.

After each shock, the industry is told to “bounce back” without being given the tools to build resilience. The rebound mechanism is consistent: currency depreciation makes Sri Lanka “affordable,” operators discount aggressively to fill rooms, and visa concessions attract price-sensitive segments. Arrivals recover, until the next shock.

This is not how a strategic export industry operates. It is how a shock-absorber behaves, used to plug forex and fiscal holes after each policy failure, then left exposed again.

The monthly 2023-2025 data illustrate the cycle perfectly. Between January 2018 and January 2023, arrivals fell 57%. The “recovery” to January 2025 shows a 103% jump over 2023, but this is bounce-back from an artificially depressed base, not structural transformation. By September 2025, growth rates normalize into the teens and twenties, catch-up to a benchmark set six years earlier.

Why the Boom Feels Like Stagnation

Industry operators report a disconnect between headline numbers and ground reality. Occupancy rates have improved to the high-60% range, but margins remain below 2018 levels. Why?

Industry operators report a disconnect between headline numbers and ground reality. Occupancy rates have improved to the high-60% range, but margins remain below 2018 levels. Why?

Because input costs, energy, food, debt servicing, have risen faster than room rates. The rupee’s collapse makes Sri Lanka look “affordable” to foreigners, but it quietly transfers value from domestic suppliers and workers to foreign visitors and lenders. Hotels fill rooms at prices that barely cover costs once translated into hard currency and adjusted for inflation.

Growth is fragile and concentrated. Europe and Asia-Pacific account for over 92% of arrivals. India alone provides 20.7% of visitors in H1 2025, and as later articles in this series will show, this is a low-yield, short-stay segment. We have built recovery on market concentration and price competition, not on product differentiation or yield optimization.

There is no credible long-term roadmap. SLTDA’s projections focus almost entirely on volumes. There is no public discussion of receipts-per-visitor targets, market composition strategies, or institutional reforms required to shift from volume to value.

The Way Forward: From Arrivals Theater to Strategic Transformation

The path out of stagnation requires uncomfortable honesty and political courage that has been systematically absent.

First, abandon arrivals as the primary success metric. Tourism contribution to economic recovery should be measured by net foreign exchange contribution after leakages, employment quality (wages, stability), and yield per visitor, not by how many planes land.

Second, establish institutional continuity. Depoliticize relevant leaderships. Implement fixed terms for key personnel insulated from political cycles. Tourism is a 30-year investment horizon; it cannot be managed on five-year electoral cycles.

Third, restore data infrastructure. Reinstate the analytics programs that track spending patterns and identify high-yield segments. Without data, we are flying blind, and no amount of ministerial optimism changes that.

Fourth, allocate resources to infrastructure. The tourism development fund exists, use it. Online promotions, BIA expansion, cultural site upgrades, last-mile connectivity cannot wait for “better fiscal conditions.” These assets generate the revenue that funds their own maintenance.

Resilience without strategy is stagnation with momentum. And stagnation, however energetically celebrated, remains stagnation.

If policymakers continue to mistake arrivals for achievement, Sri Lanka will remain trapped in a cycle: crash, discount, recover, repeat. Meanwhile, competitors will consolidate high-yield models, and we will wonder why our tourism “boom” generates less cash, less jobs, and less development than it should.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

The call for review of reforms in education: discussion continues …

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The statement by 94 university teachers deplores the high handed manner in which the reforms were hastily formulated, and without public consultation. It underlines the problems with the substance of the reforms, particularly in the areas of the structure of education, and the content of the text books. The problem lies at the very outset of the reforms, with the conceptual framework. While the stated conceptualisation sounds fancifully democratic, inclusive, grounded and, simultaneously, sensitive, the detail of the reforms-structure itself shows up a scandalous disconnect between the concept and the structural features of the reforms. This disconnect is most glaring in the way the secondary school programme, in the main, the junior and senior secondary school Phase I, is structured; secondly, the disconnect is also apparent in the pedagogic areas, particularly in the content of the text books. The key players of the “Reforms” have weaponised certain seemingly progressive catch phrases like learner- or student-centred education, digital learning systems, and ideas like moving away from exams and text-heavy education, in popularising it in a bid to win the consent of the public. Launching the reforms at a school recently, Dr. Amarasuriya says, and I cite the state-owned broadside Daily News here, “The reforms focus on a student-centered, practical learning approach to replace the current heavily exam-oriented system, beginning with Grade One in 2026 (https://www.facebook.com/reel/1866339250940490). In an address to the public on September 29, 2025, Dr. Amarasuriya sings the praises of digital transformation and the use of AI-platforms in facilitating education (https://www.facebook.com/share/v/14UvTrkbkwW/), and more recently in a slightly modified tone (https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/PM-pledges-safe-tech-driven-digital-education-for-Sri-Lankan-children/108-331699).

The idea of learner- or student-centric education has been there for long. It comes from the thinking of Paulo Freire, Ivan Illyich and many other educational reformers, globally. Freire, in particular, talks of learner-centred education (he does not use the term), as transformative, transformative of the learner’s and teacher’s thinking: an active and situated learning process that transforms the relations inhering in the situation itself. Lev Vygotsky, the well-known linguist and educator, is a fore runner in promoting collaborative work. But in his thought, collaborative work, which he termed the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is processual and not goal-oriented, the way teamwork is understood in our pedagogical frameworks; marks, assignments and projects. In his pedagogy, a well-trained teacher, who has substantial knowledge of the subject, is a must. Good text books are important. But I have seen Vygotsky’s idea of ZPD being appropriated to mean teamwork where students sit around and carry out a task already determined for them in quantifying terms. For Vygotsky, the classroom is a transformative, collaborative place.

But in our neo liberal times, learner-centredness has become quick fix to address the ills of a (still existing) hierarchical classroom. What it has actually achieved is reduce teachers to the status of being mere cogs in a machine designed elsewhere: imitative, non-thinking followers of some empty words and guide lines. Over the years, this learner-centred approach has served to destroy teachers’ independence and agency in designing and trying out different pedagogical methods for themselves and their classrooms, make input in the formulation of the curriculum, and create a space for critical thinking in the classroom.

Thus, when Dr. Amarasuriya says that our system should not be over reliant on text books, I have to disagree with her (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/29/education-reform-to-end-textbook-tyranny ). The issue is not with over reliance, but with the inability to produce well formulated text books. And we are now privy to what this easy dismissal of text books has led us into – the rabbit hole of badly formulated, misinformed content. I quote from the statement of the 94 university teachers to illustrate my point.

“The textbooks for the Grade 6 modules . . . . contain rampant typographical errors and include (some undeclared) AI-generated content, including images that seem distant from the student experience. Some textbooks contain incorrect or misleading information. The Global Studies textbook associates specific facial features, hair colour, and skin colour, with particular countries and regions, and refers to Indigenous peoples in offensive terms long rejected by these communities (e.g. “Pygmies”, “Eskimos”). Nigerians are portrayed as poor/agricultural and with no electricity. The Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy textbook introduces students to “world famous entrepreneurs”, mostly men, and equates success with business acumen. Such content contradicts the policy’s stated commitment to “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Is this the kind of content we want in our textbooks?”

Where structure is concerned, it is astounding to note that the number of subjects has increased from the previous number, while the duration of a single period has considerably reduced. This is markedly noticeable in the fact that only 30 hours are allocated for mathematics and first language at the junior secondary level, per term. The reduced emphasis on social sciences and humanities is another matter of grave concern. We have seen how TV channels and YouTube videos are churning out questionable and unsubstantiated material on the humanities. In my experience, when humanities and social sciences are not properly taught, and not taught by trained teachers, students, who will have no other recourse for related knowledge, will rely on material from controversial and substandard outlets. These will be their only source. So, instruction in history will be increasingly turned over to questionable YouTube channels and other internet sites. Popular media have an enormous influence on the public and shapes thinking, but a well formulated policy in humanities and social science teaching could counter that with researched material and critical thought. Another deplorable feature of the reforms lies in provisions encouraging students to move toward a career path too early in their student life.

The National Institute of Education has received quite a lot of flak in the fall out of the uproar over the controversial Grade 6 module. This is highlighted in a statement, different from the one already mentioned, released by influential members of the academic and activist public, which delivered a sharp critique of the NIE, even while welcoming the reforms (https://ceylontoday.lk/2026/01/16/academics-urge-govt-safeguard-integrity-of-education-reforms). The government itself suspended key players of the NIE in the reform process, following the mishap. The critique of NIE has been more or less uniform in our own discussions with interested members of the university community. It is interesting to note that both statements mentioned here have called for a review of the NIE and the setting up of a mechanism that will guide it in its activities at least in the interim period. The NIE is an educational arm of the state, and it is, ultimately, the responsibility of the government to oversee its function. It has to be equipped with qualified staff, provided with the capacity to initiate consultative mechanisms and involve panels of educators from various different fields and disciplines in policy and curriculum making.

In conclusion, I call upon the government to have courage and patience and to rethink some of the fundamental features of the reform. I reiterate the call for postponing the implementation of the reforms and, in the words of the statement of the 94 university teachers, “holistically review the new curriculum, including at primary level.”

(Sivamohan Sumathy was formerly attached to the University of Peradeniya)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Sivamohan Sumathy

Features

Constitutional Council and the President’s Mandate

The Constitutional Council stands out as one of Sri Lanka’s most important governance mechanisms particularly at a time when even long‑established democracies are struggling with the dangers of executive overreach. Sri Lanka’s attempt to balance democratic mandate with independent oversight places it within a small but important group of constitutional arrangements that seek to protect the integrity of key state institutions without paralysing elected governments. Democratic power must be exercised, but it must also be restrained by institutions that command broad confidence. In each case, performance has been uneven, but the underlying principle is shared.

Comparable mechanisms exist in a number of democracies. In the United Kingdom, independent appointments commissions for the judiciary and civil service operate alongside ministerial authority, constraining but not eliminating political discretion. In Canada, parliamentary committees scrutinise appointments to oversight institutions such as the Auditor General, whose independence is regarded as essential to democratic accountability. In India, the collegium system for judicial appointments, in which senior judges of the Supreme Court play the decisive role in recommending appointments, emerged from a similar concern to insulate the judiciary from excessive political influence.

The Constitutional Council in Sri Lanka was developed to ensure that the highest level appointments to the most important institutions of the state would be the best possible under the circumstances. The objective was not to deny the executive its authority, but to ensure that those appointed would be independent, suitably qualified and not politically partisan. The Council is entrusted with oversight of appointments in seven critical areas of governance. These include the judiciary, through appointments to the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, the independent commissions overseeing elections, public service, police, human rights, bribery and corruption, and the office of the Auditor General.

JVP Advocacy

The most outstanding feature of the Constitutional Council is its composition. Its ten members are drawn from the ranks of the government, the main opposition party, smaller parties and civil society. This plural composition was designed to reflect the diversity of political opinion in Parliament while also bringing in voices that are not directly tied to electoral competition. It reflects a belief that legitimacy in sensitive appointments comes not only from legal authority but also from inclusion and balance.

The idea of the Constitutional Council was strongly promoted around the year 2000, during a period of intense debate about the concentration of power in the executive presidency. Civil society organisations, professional bodies and sections of the legal community championed the position that unchecked executive authority had led to abuse of power and declining public trust. The JVP, which is today the core part of the NPP government, was among the political advocates in making the argument and joined the government of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga on this platform.

The first version of the Constitutional Council came into being in 2001 with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution during the presidency of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. The Constitutional Council functioned with varying degrees of effectiveness. There were moments of cooperation and also moments of tension. On several occasions President Kumaratunga disagreed with the views of the Constitutional Council, leading to deadlock and delays in appointments. These experiences revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of the model.

Since its inception in 2001, the Constitutional Council has had its ups and downs. Successive constitutional amendments have alternately weakened and strengthened it. The 18th Amendment significantly reduced its authority, restoring much of the appointment power to the executive. The 19th Amendment reversed this trend and re-established the Council with enhanced powers. The 20th Amendment again curtailed its role, while the 21st Amendment restored a measure of balance. At present, the Constitutional Council operates under the framework of the 21st Amendment, which reflects a renewed commitment to shared decision making in key appointments.

Undermining Confidence

The particular issue that has now come to the fore concerns the appointment of the Auditor General. This is a constitutionally protected position, reflecting the central role played by the Auditor General’s Department in monitoring public spending and safeguarding public resources. Without a credible and fearless audit institution, parliamentary oversight can become superficial and corruption flourishes unchecked. The role of the Auditor General’s Department is especially important in the present circumstances, when rooting out corruption is a stated priority of the government and a central element of the mandate it received from the electorate at the presidential and parliamentary elections held in 2024.

So far, the government has taken hitherto unprecedented actions to investigate past corruption involving former government leaders. These actions have caused considerable discomfort among politicians now in the opposition and out of power. However, a serious lacuna in the government’s anti-corruption arsenal is that the post of Auditor General has been vacant for over six months. No agreement has been reached between the government and the Constitutional Council on the nominations made by the President. On each of the four previous occasions, the nominees of the President have failed to obtain its concurrence.

The President has once again nominated a senior officer of the Auditor General’s Department whose appointment was earlier declined by the Constitutional Council. The key difference on this occasion is that the composition of the Constitutional Council has changed. The three representatives from civil society are new appointees and may take a different view from their predecessors. The person appointed needs to be someone who is not compromised by long years of association with entrenched interests in the public service and politics. The task ahead for the new Auditor General is formidable. What is required is professional competence combined with moral courage and institutional independence.

New Opportunity

By submitting the same nominee to the Constitutional Council, the President is signaling a clear preference and calling it to reconsider its earlier decision in the light of changed circumstances. If the President’s nominee possesses the required professional qualifications, relevant experience, and no substantiated allegations against her, the presumption should lean toward approving the appointment. The Constitutional Council is intended to moderate the President’s authority and not nullify it.

A consensual, collegial decision would be the best outcome. Confrontational postures may yield temporary political advantage, but they harm public institutions and erode trust. The President and the government carry the democratic mandate of the people; this mandate brings both authority and responsibility. The Constitutional Council plays a vital oversight role, but it does not possess an independent democratic mandate of its own and its legitimacy lies in balanced, principled decision making.

Sri Lanka’s experience, like that of many democracies, shows that institutions function best when guided by restraint, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to the public good. The erosion of these values elsewhere in the world demonstrates their importance. At this critical moment, reaching a consensus that respects both the President’s mandate and the Constitutional Council’s oversight role would send a powerful message that constitutional governance in Sri Lanka can work as intended.

by Jehan Perera

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition