Features

Seeing the market through the spectre

By Panduka Karunanayake

Leftist ideologues like to create an image of ‘the market’ as a terrible place, like how grown-ups frighten children with their ghost stories. The market is portrayed as a ruthless, heartless machine that thrives on unfairness and corruption, crushing the poor and fattening the rich. It must have become easier to create this image after the Soviet bloc fell in the 1990s and China emerged out of communism soon afterwards, because after that people quickly forgot that socialist and communist economies too have markets – even markets every bit as ruthless, heartless, unfair and corrupt as any capitalist market. Today, these ideologues can write as if the market and capitalism are synonyms. Everything ‘un-socialist’ can be easily ‘explained away’ by saying that it ‘promotes marketisation’.

No amount of argument or explanation would change these ideologues’ minds – after all, an ideologue is a person who pursues an ideology in an inflexible manner. But let me set out some related matters, for the benefit of the rest of us.

Emergence and evolution of the market

Markets have probably existed throughout human existence, because human beings are social animals that thrive on social interaction. There is an illuminating passage in Charles Darwin’s book The Voyage of the Beagle, where he described an encounter with the inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego in South America, who were ‘primitive’ hunter-gatherers and nomads with no previous encounter with civilisation:

“Some of the Feugians plainly showed that they had a fair notion of barter. I gave one man a large nail (a most valuable present) without making any signs for a return; but he immediately picked out two fish, and handed them up on the point of his spear. If any present was designed for one canoe, and it fell near another, it was invariably given to the right owner.”

This passage shows that they were well-versed in the moral principles – such as free choice, trust, fairness and reciprocity – associated with exchange of goods and services that form the basis of the functioning market.

The market became prominent after the emergence of agriculture about 10,000 year ago. Agriculture enabled farmers to produce a food surplus, which then enabled the rest of the villagers to work on other crafts – promoting division of labour and specialisation. This created an overall increase in the quality of the villagers’ lives, because they now had a wider variety of produce to consume. Villagers now depended on each other more, for the produce they wished to consume. As the village increased in size and complexity, a place where producers and consumers could meet, to exchange goods and services, became a necessity. In the physical realm this was the marketplace, and in the conceptual realm it was the market. Initially, exchange occurred through the barter system without a medium of exchange, but the invention of money made it easier.

But until industrialisation, this market was small and sluggish. It produced very little, compared to today. Most of what a village produced was consumed within it, and only a tiny proportion of it left the village, to be consumed by outsiders – the market was still not much more than the marketplace.

Reason for smallness

The reason for this smallness was not entirely because there were no industrial factories. The villagers could have produced more if they wanted to, but they didn’t, because they saw that any extra produce created problems. There were difficulties with storing it, protecting it, preserving it or transporting it elswhere, and in any event the lords could easily expropriate it under the feudalistic modes of production. Items that were considered luxury items were an exception; they were carried to distant destinations by camel, caravan or boat.

But starting in the eighteenth century, industrialisation changed all that. Factories produced large quantities of produce (or ‘commodities’) cheaply, and the market expanded to distribute a much larger variety and quantity of goods much more widely. Specialisation became the norm and a necessity. The crucial factor that made all this possible was probably the improvement in transport. Look at your lunch plate today, and try to figure out from where and how far each of the food items on it – not to mention the plate itself or the energy for the fire that cooked your lunch – have come from.

Today, production and consumption are almost totally separated from each other (with a few exceptions, like farmers who sell their produce by the roadside in front of their homes, and ‘factory outlets’). It is the market that enables this to happen. The market, which is no longer simply the marketplace, gives us access to a bewildering variety of goods and services, thereby enabling us – even the poorest amongst us – to enjoy a greater choice and higher quality of life, compared to pre-industrial times. The healthcare and education that even the poorest amongst us enjoy would not reach them if not for the market.

As an example, let us take soap. Until industrialisation this was a luxury item that only the elite enjoyed. In Roman times, even the elite cleaned themselves mostly by simply immersing themselves in their baths and rubbing off dirt; indeed, using soap would have made the bath too disgusting to get into. Soap was available only to those in the very highest echelons of society. The masses were ‘dirty’ and their skin was infested with scabies, pediculosis and lice, and they commonly suffered diseases like impetigo and erysipelas – they lacked even the water necessary to wash themselves (especially hot water in cold climates). But today, soap is so ubiquitous that we take it for granted – it was industrialisation that enabled its cheap mass production and the market that enabled its wide distribution.

Value of simple things

The real value of something as simple as soap was driven home powerfully to me in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami, when people had lost everything and were accommodated in make-shift camps. What did they ask for, from the donors and volunteers who went to help them? First, they asked for food, water and certain medicines. A few days later, they began asking for soap, a change of clothing and sanitary pads: after three or four days, they were itching and suffering with fungal skin infections. That was an unfortunate re-enactment and reminder of the pre-industrial life of the masses. I remembered how a textbook of public health that I had read a few decades earlier had cleverly classified infectious diseases according to whether they were prevented by soap and water, clean drinking water, safe food, and so on. The post-tsunami experience showed me the sagacity of that – and the value of the ubiquitous soap, industrialisation and the market.

In his book The Third Wave, Alvin Toffler compared a modern-day market to an efficient telephone exchange or switchboard. A switchboard connects thousands of senders and recipients accurately and enables messages to be sent across to their intended destinations – like producers, consumers, and goods and services in the market. Like telephone messages, goods and services are produced, sent across and consumed according to need and availability: demand and supply.

Such a market cannot exist on its own. It needs inputs from important sectors in society, such as law and order (which upholds the right to private property, prevents or punishes theft, and arbitrates when there are contractual disagreements), education (which creates an educated and trained workforce, not only for manufacture but also for distribution), communication, energy, transport, ports, etc. Such external supports have existed not only in capitalist markets but also in pre-capitalist and socialist markets. These supports are provided because everybody realises that markets are useful to everyone, especially when the population expands and the demand for commodities increases.

So, to say that something should be abhorred because it promotes ‘marketisation’ is disingenuous.

Organising the market

Markets can be organised in various ways. It helps to think of these as lying on a spectrum ranging from capitalism to communism, which are the extreme forms at the two ends. In-between, there are lots of compromises, combinations or ‘middle ways’. For instance, the current Chineses model is sometimes called state capitalism – a good example of a middle way.

But the natural form of the market that emerged spontaneously was the free market: a market where no authority-imposed restrictions or controls, nor introduced any encouragements or inducements. The activities in the free market merely recognised the concepts of private property and voluntary exchange, and operated on demand and supply. That was all.

Opponents

Throughout this time, the free market has had many opponents who have tried to impose limits or controls to it. Division of labour and specialisation were resisted – by the cultural elite who tried to maintain the status quo in society, such as the caste system in ancient society and feudal-peasant relations in medieval times. During industrialisation when factories came up, that was resisted too – by guildsmen who felt that their business was threatened, and those like the Luddites who felt threatened by the new manufacturing technology. Karl Marx proposed that private property, including ‘the means of production’, should be taken over by the state and brought under its control.

Some of the concepts that they used against the growth of the free market were traditional values such as loyalty and caste-based duties (especially upheld by the cultural elite), simplicity in life and charity as well as opposition to ‘ursury’ and banks (especially the clergy), and equality. It is only now, after centuries of change, that words like ‘industry’ (which initially meant industriousness), ‘entrepreneurship’ and ‘individualism’ have emerged as ‘good words’, to create an environment conducive to a free market. Charles Dickens’ novel Martin Chuzzlewit nicely captured the mood of the era when industrialisation was struggling to emerge through the feudal society, by portraying the struggle of a typical ‘upstart’ who had to go to America to make a fresh start.

According to Stephen Fry, even today, the typical British comedy mostly parodies the upstart’s ineptness (“celebrate failure”), whereas the typical American comedy glorifies the industrious entrepreneur or smart-aleck (“life is improvable”). When we read comments about the market, we must take care to ‘read’ this subtext too.

Inequality

Ironically, inequality had previously been tolerated and even celebrated, as long as the only inequality was between the elite and the masses – the masses were ‘equal’ in their poverty and the elite were rich by birthright. But after industrialisation, the moment the masses gradually became enriched and a middle class emerged, inequality became a big social issue. When a part of the masses remained poor and another part became better-off, socialism was born. Different segments of the masses quickly became each other’s enemies – thanks to socialism. It was an example of applying the brakes even before the vehicle had started to move in earnest. They were ennobled by socialism’s new words, like ‘fraternity’ and ‘equality’ – which basically meant, ‘Those who are not poor like you are not one of you, and have no right to be rich if you too cannot be rich’.

But while the leaders of socialism may have harboured such beliefs, their proletariat comrades had simpler minds. In his book The Road to Wigan Pier written after World War One, George Orwell, himself a socialist, reflecting on the tensions and contradictions in English society as it grappled with this new-found inequality and ‘class struggle’, wrote:

“To the ordinary working man, the sort you would meet in any pub on Saturday night, Socialism does not mean much more than better wages and shorter hours and nobody bossing you about….[No] genuine working man grasps the deeper implications of Socialism. Often, in my opinion, he is a truer Socialist than the orthodox Marxist, because he does remember what the other so often forgets, that Socialism means justice and common decency….His vision of the Socialist future is a vision of present society with the worst abuses left out, and with interest centring round the same things as at present – family life, the pub, football, and local politics.”

Orwell’s main message was that any effort to ‘improve’ society, by whatever name, that had lost touch with the common man was bound to deteriorate into a fascism. The remainder of the twentieth century proved him right.

Today, Orwell’s England has come through quite nicely in spite of the disintegration of the British Empire soon afterwards, and shows none of the class struggle and poverty Orwell’s and Dickens’ books have recorded. So, should we champion an equality of the poor, or should we patiently work towards a gradually enriching society with a tolerable level of inequality?

Necessary controls

At the same time, it is also advisable to control some forms of exchange in the market. For instance, if a country considers that it is necessary to ensure food security through its own, local cultivation of important crops, it is wise to put in place some safeguards to protect local agriculture from the adverse effects of competition from imported foods, at least for important foods. Even advanced capitalist countries like USA and Japan do this (for wheat and rice, respectively).

Similarly, it would be prudent to protect certain crucial markets, such as the energy sector and ports. It is also important to ensure distribution of crucial goods & services (such as healthcare, basic education, basic housing, basic clothing, basic transport) for all members of society, with a view to protecting the poor who have limited purchasing power. This requires the institution of safety nets and price control. In this age of climate change, resource depletion and environmental degradation, nobody would argue against environmental protection, which naturally requires the imposition of certain restrictions on the free market. Finally, nobody would argue that sectors such as national defence and law & order should be floated in the free market. So markets do need judicious controls and regulation.

More than ‘free’

On the flip side, in some markets there are mechanisms created specifically to encourage a bigger flow of goods & services than what the natural, ‘free’ market would sustain. These include patent laws, laws restricting monopolies, bankruptcy laws, the financial and share market, and so on; some of them may be good, while others are not.

The market is then not merely a place of exchange; it is also a place to make massive profits, where the falling crumbs accumulate to produce huge volumes of ‘wealth’. There are those who would profit exactly from this, while such ‘wealth generation’ or ‘productivity’ brings no intrinsic value to society while needlessly destroying our environment and culture – this can then become the new status quo that these new elite wish to protect.

Conclusion

A free market would promote exchange of goods & services and increase the volume of exchange, and this in turn would increase employment, productivity, taxation and funds for welfare expenditure. Both restricting it and encouraging it, while sometimes necessary, must be done only cautiously. Naturally, therefore, both extremes – and their supportive ideologies – are not good. What we need to have is a ‘middle-way’ market that enables enough economic activity and protects the poor, while protecting the environment for future generations.

So, there is no need to fear the market. What we need to do is understand it, be able to predict its behaviour, and try to modify it so that it creates the benefits we need and avoids harm. The child must grow up, overcome the fear of ghosts and learn to deal with darkness. Disingenuous, sleight-of-hand arguments that promote the darkness are of no use, and their supportive ideologies can only lead to fascism – as the twentieth century amply taught us.

The writer teaches medicine in the University of Colombo (email:

panduka@clinmed.cmb.ac.lk). He acknowledges helpful comments from Professor Sirimal Abeyratne (Professor of Economics, University of Colombo) and Dr G. Usvatte-aratchi.

Features

Why TV debates won’t stop the killing

On Friday, 5th December, ITN’s Hathweni Peya turned its spotlight on road safety, a subject as urgent as it is lethal. True to the grand tradition of Sri Lankan television panels, the discussion featured a consultant neurosurgeon and a professor representing the road safety subcommittee. Yet, conspicuously absent were voices that could have grounded the debate in lived reality: a traffic police representative, a Transport Ministry official armed with hard statistics, and grieving family members whose tragedies often provide the emotional anchor and, admittedly, the inevitable B-roll, for such conversations.

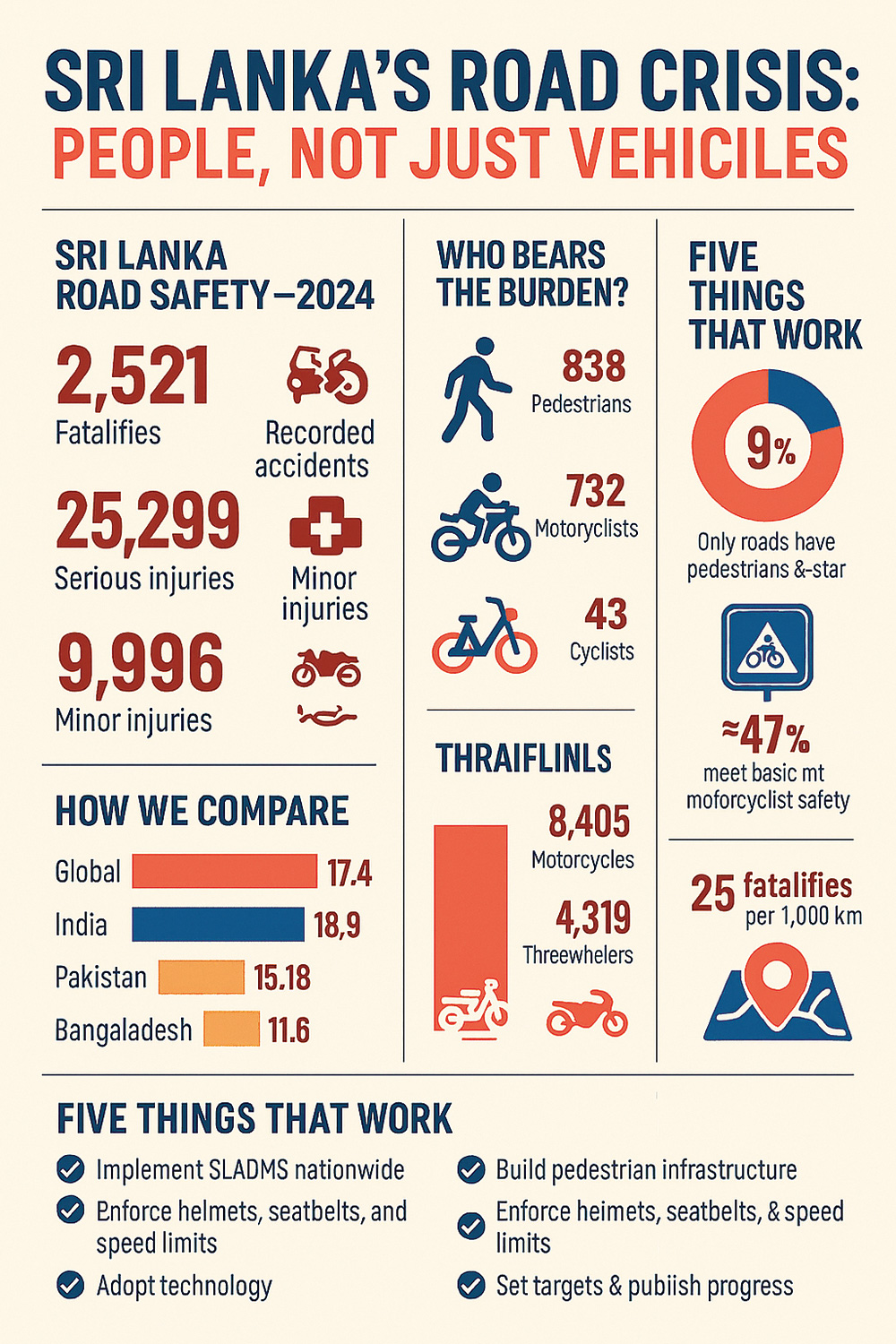

Having covered these performances for three decades, I can write the script with my eyes closed. In 2024, 2,521 people died on our roads, a 6.7% increase from 2020. While we recycle the same talking points about “reckless or stressful drivers,” the data suggests that the problem isn’t just not only the people behind the wheel but also the people behind the desks.

We are witnessing a systemic failure, disguised as a discipline problem. And, frankly, the numbers are screaming what our policymakers refuse to hear.

“Discipline” Myth vs. The Data

Let’s address the elephant in the room: Sri Lankan drivers are indeed chaotic. The police will tell you there were 1,651 speeding cases involving bus drivers last year alone. But here is the uncomfortable truth: we have been having this exact conversation about discipline for 20 years.

If the medicine hasn’t worked for two decades, maybe the diagnosis is wrong.

A 2023 study in “Accident Analysis & Prevention” found that developing countries stuck in the “awareness campaign” phase typically see fatality reductions of less than 2%. Countries that shift focus to infrastructure engineering and automated enforcement achieve reductions of 15-25%.

Between 2016 and 2021, Sri Lanka managed a pathetic 3.6% annual decrease in fatality rates. The Asia-Pacific region managed 19%. Even South Asia, hardly a beacon of safety, averaged a 10% reduction. We aren’t just failing; we are failing to be competitive at keeping our citizens alive.

The Global Context: A Comparative Shame

To understand the depth of our failure, we must look beyond our shores. Our officials like to claim our fatality rate (11.5 per 100,000 population) is “manageable” compared to the global average. This is a statistical sleight of hand.

Look at Ukraine. Despite fighting an active war, facing missile strikes and destroyed infrastructure, Ukraine manages to maintain a sophisticated accident data system. They know exactly that 41.5% of their accidents are speeding-related. They are deploying AI-driven enforcement. If a country under siege can modernise its road safety, what is our excuse?

Look at India. Dealing with 295 million vehicles and chaotic urbanisation, India has rolled out the iRAD (Integrated Road Accident Database) across 28 states. They are not just counting bodies; they are analysing causes.

The Infrastructure Nobody Wants to Discuss

Here is the statistic that should have stopped the show on Hathweni Peya: Only 9% of Sri Lankan roads are rated 3-stars or better for pedestrians. According to the International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP), this means 91% of our road network is statistically unsafe for anyone walking. Yet, pedestrians accounted for 838 deaths in 2024, the highest single category.

When an engineer designs a high-speed road through a town without a sidewalk or a safe crossing, and a pedestrian or cyclist is killed in a sidewalk it, we call the pedestrian/cyclist “undisciplined.” In reality, they are victims of design malpractice.

In advanced economies, motorists are required to maintain at least a one-meter clearance when overtaking a cyclist or pedestrian. In Sri Lanka, however, the reality feels alarmingly different—vehicles often whiz past so close that you can almost feel them brushing your ear, even when you’re walking on the correct side of the road. I’ve personally experienced this during my regular morning walks. Adding to the chaos, drivers frequently stop in the middle of the road to buy kola kenda (herbal porridge) or flowers. I’ve witnessed such scenes right in front of the Mahamevnawa Temple and even managed to capture a few incidents, which I’d like to share with our readers.

The situation for motorcyclists is equally grim. They accounted for 732 deaths and were involved in the highest number of accidents (8,405). Yet only 47% of our roads meet basic safety standards for two-wheelers. We have built a road network for cars in a country where the majority drive scooters or take the bus. (See Figure 1)

The Data Scandal: SLADMS

Perhaps the most infuriating aspect of this crisis is the “Sri Lanka Accident Data Management System” (SLADMS). This state-of-the-art system was developed to replace our antiquated paper-based records. It allows for GPS mapping of accidents, hotspot identification, and predictive modelling.

It exists. We paid for it. But it has not been implemented nationwide.

Instead, we continue to use the outdated Micro Accident Analysis Programme (MAAP), effectively shooting in the dark. While the world moves toward machine learning for accident prediction, our intervention strategy is wait for a crash, express outrage, repeat.

Every day SLADMS remains offline is an act of administrative negligence. You cannot fix what you cannot measure.

The Economic Cost of Inaction

If the moral argument doesn’t move our politicians, perhaps the financial one will. The WHO estimates that road crashes cost countries, like Sri Lanka, up to 3% of their GDP annually.

Do the math. We are hemorrhaging approximately Rs. 300-350 billion every year due to road accidents. This includes medical costs, lost productivity, property damage, and the long-term economic loss of young, working-age citizens.

In 2024 alone, 572 people were killed just in the first quarter. Young males aged 15-34 account for 60-80% of traffic deaths globally. We are wiping out our workforce and then complaining about economic stagnation.

A 2024 World Bank analysis suggests that every 1% reduction in traffic fatalities generates economic benefits equal to 0.12% of GDP. If we simply achieved the Asia-Pacific average for safety improvement, we could inject billions back into the national economy.

Getting driving license

In advanced economies, the process of earning a driver’s license begins with a learner’s permit, often issued as early as age 15, under strict conditions, such as prohibiting passengers. The subsequent driving test is so rigorous that even seasoned bus drivers from Sri Lanka, with 10–20 years of experience, often fail when attempting it abroad. I plan to write a separate article detailing this test, but in the meantime, I invite readers to explore platforms like Perplexity.ai or Google to see how these examinations are structured.

A Modest Proposal for Future Episodes

If Hathweni Peya, or any media outlet, truly wants to serve the public, we need to stop the theatre. The next time a Minister or Traffic Chief sits in that chair, don’t ask them how we can “improve discipline.” Ask them this:

SLADMS Deployment: Give Us a Date:

The Sri Lanka Accident Data Management System (SLADMS) has been in discussion for years.

Audit the Unsafe Roads:

Where is the audit for the 91% of roads classified as unsafe?

Automated Enforcement, Not 19th-Century Checkpoints:

Police checkpoints belong to another era. We need speed cameras and red-light cameras, systems that don’t take bribes, don’t get tired, and enforce the law consistently. When will automated enforcement become a reality?

Budget Transparency:

Road safety is not a cost, it’s an investment. Every $1 spent saves $4–$6 in avoided crashes and healthcare costs.

Rigorous Driving Tests:

When will Sri Lanka introduce written and practical driving tests comparable to advanced economies? Current standards are inadequate and contribute to systemic risk.

The Way Forward

The solutions are hiding in plain sight. They aren’t sexy. They involve building sidewalks, enforcing helmet laws with no exceptions, separating motorcycle lanes, and letting computers handle the ticketing.

Countries poorer and more chaotic than Sri Lanka have managed to lower their death tolls. Vietnam reduced motorcycle deaths by 32% in five years through infrastructure changes. Rwanda achieved a 40% reduction in fatalities through strict vehicle inspections.

We can continue to blame the “reckless or stressful driver” if it is a convenient scapegoat that absolves the state of its duty to protect its citizens.

The next traffic death will occur in approximately 1-2 hours. It is not an accident. It is a predictable result of a system we have chosen not to fix.

Features

Handunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

“My tongue in English chains.

I return, after a generation, to you.

I am at the end

of my Dravidic tether

hunger for you unassuaged

I falter, stumble.”

– Indian poet R. Parthasarathy

When Minister Sunil Handunnetti addressed the World Economic Forum’s ‘Is Asia’s Century at Risk?’ discussion as part of the Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2025 in June 2025, I listened carefully both to him and the questions that were posed to him by the moderator. The subsequent trolling and extremely negative reactions to his use of English were so distasteful that I opted not to comment on it at the time. The noise that followed also meant that a meaningful conversation based on that event on the utility of learning a powerful global language and how our politics on the global stage might be carried out more successfully in that language was lost on our people and pundits, barring a few commentaries.

When Minister Sunil Handunnetti addressed the World Economic Forum’s ‘Is Asia’s Century at Risk?’ discussion as part of the Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2025 in June 2025, I listened carefully both to him and the questions that were posed to him by the moderator. The subsequent trolling and extremely negative reactions to his use of English were so distasteful that I opted not to comment on it at the time. The noise that followed also meant that a meaningful conversation based on that event on the utility of learning a powerful global language and how our politics on the global stage might be carried out more successfully in that language was lost on our people and pundits, barring a few commentaries.

Now Handunnetti has reopened the conversation, this time in Sri Lanka’s parliament in November 2025, on the utility of mastering English particularly for young entrepreneurs. In his intervention, he also makes a plea not to mock his struggle at learning English given that he comes from a background which lacked the privilege to master the language in his youth. His clear intervention makes much sense.

The same ilk that ridiculed him when he spoke at WEF is laughing at him yet again on his pronunciation, incomplete sentences, claiming that he is bringing shame to the country and so on and so forth. As usual, such loud, politically motivated and retrograde critics miss the larger picture. Many of these people are also among those who cannot hold a conversation in any of the globally accepted versions of English. Moreover, their conceit about the so-called ‘correct’ use of English seems to suggest the existence of an ideal English type when it comes to pronunciation and basic articulation. I thought of writing this commentary now in a situation when the minister himself is asking for help ‘in finding a solution’ in his parliamentary speech even though his government is not known to be amenable to critical reflection from anyone who is not a party member.

The remarks at the WEF and in Sri Lanka’s parliament are very different at a fundamental level, although both are worthy of consideration – within the realm of rationality, not in the depths of vulgar emotion and political mudslinging.

The problem with Handunnetti’s remarks at WEF was not his accent or pronunciation. After all, whatever he said could be clearly understood if listened to carefully. In that sense, his use of English fulfilled one of the most fundamental roles of language – that of communication. Its lack of finesse, as a result of the speaker being someone who does not use the language professionally or personally on a regular basis, is only natural and cannot be held against him. This said, there are many issues that his remarks flagged that were mostly drowned out by the noise of his critics.

Given that Handunnetti’s communication was clear, it also showed much that was not meant to be exposed. He simply did not respond to the questions that were posed to him. More bluntly, a Sinhala speaker can describe the intervention as yanne koheda, malle pol , which literally means, when asked ‘Where are you going?’, the answer is ‘There are coconuts in the bag’.

He spoke from a prepared text which his staff must have put together for him. However, it was far off the mark from the questions that were being directly posed to him. The issue here is that his staff appears to have not had any coordination with the forum organisers to ascertain and decide on the nature of questions that would be posed to the Minister for which answers could have been provided based on both global conditions, local situations and government policy. After all, this is a senior minister of an independent country and he has the right to know and control, when possible, what he is dealing with in an international forum.

This manner of working is fairly routine in such international fora. On the one hand, it is extremely unfortunate that his staff did not do the required homework and obviously the minister himself did not follow up, demonstrating negligence, a want for common sense, preparedness and experience among all concerned. On the other hand, the government needs to have a policy on who it sends to such events. For instance, should a minister attend a certain event, or should the government be represented by an official or consultant who can speak not only fluently, but also with authority on the subject matter. That is, such speakers need to be very familiar with the global issues concerned and not mere political rhetoric aimed at local audiences.

Other than Handunnetti, I have seen, heard and also heard of how poorly our politicians, political appointees and even officials perform at international meetings (some of which are closed door) bringing ridicule and disastrous consequences to the country. None of them are, however, held responsible.

Such reflective considerations are simple yet essential and pragmatic policy matters on how the government should work in these conditions. If this had been undertaken, the WEF event might have been better handled with better global press for the government. Nevertheless, this was not only a matter of English. For one thing, Handunnetti and his staff could have requested for the availability of simultaneous translation from Sinhala to English for which pre-knowledge of questions would have been useful. This is all too common too. At the UN General Assembly in September, President Dissanayake spoke in Sinhala and made a decent presentation.

The pertinent question is this; had Handunetti had the option of talking in Sinhala, would the interaction have been any better? That is extremely doubtful, barring the fluency of language use. This is because Handunnetti, like most other politicians past and present, are good at rhetoric but not convincing where substance is concerned, particularly when it comes to global issues. It is for this reason that such leaders need competent staff and consultants, and not mere party loyalists and yes men, which is an unfortunate situation that has engulfed the whole government.

What about the speech in parliament? Again, as in the WEF event, his presentation was crystal clear and, in this instance, contextually sensible. But he did not have to make that speech in English at all when decent simultaneous translation services were available. In so far as content was concerned, he made a sound argument considering local conditions which he knows well. The minister’s argument is about the need to ensure that young entrepreneurs be taught English so that they can deal with the world and bring investments into the country, among other things. This should actually be the norm, not only for young entrepreneurs, but for all who are interested in widening their employment and investment opportunities beyond this country and in accessing knowledge for which Sinhala and Tamil alone do not suffice.

As far as I am concerned, Handunetti’s argument is important because in parliament, it can be construed as a policy prerogative. Significantly, he asked the Minister of Education to make this possible in the educational reforms that the government is contemplating.

He went further, appealing to his detractors not to mock his struggle in learning English, and instead to become part of the solution. However, in my opinion, there is no need for the Minister to carry this chip on his shoulder. Why should the minister concern himself with being mocked for poor use of English? But there is a gap that his plea should have also addressed. What prevented him from mastering English in his youth goes far deeper than the lack of a privileged upbringing.

The fact of the matter is, the facilities that were available in schools and universities to learn English were not taken seriously and were often looked down upon as kaduwa by the political spectrum he represents and nationalist elements for whom the utilitarian value of English was not self-evident. I say this with responsibility because this was a considerable part of the reality in my time as an undergraduate and also throughout the time I taught in Sri Lanka.

Much earlier in my youth, swayed by the rhetoric of Sinhala language nationalism, my own mastery of English was also delayed even though my background is vastly different from the minister. I too was mocked, when two important schools in Kandy – Trinity College and St. Anthony’s College – refused to accept me to Grade 1 as my English was wanting. This was nearly 20 years after independence. I, however, opted to move on from the blatant discrimination, and mastered the language, although I probably had better opportunities and saw the world through a vastly different lens than the minister. If the minister’s commitment was also based on these social and political realities and the role people like him had played in negating our English language training particularly in universities, his plea would have sounded far more genuine.

If both these remarks and the contexts in which they were made say something about the way we can use English in our country, it is this: On one hand, the government needs to make sure it has a pragmatic policy in place when it sends representatives to international events which takes into account both a person’s language skills and his breadth of knowledge of the subject matter. On the other hand, it needs to find a way to ensure that English is taught to everyone successfully from kindergarten to university as a tool for inclusion, knowledge and communication and not a weapon of exclusion as is often the case.

This can only bear fruit if the failures, lapses and strengths of the country’s English language teaching efforts are taken into cognizance. Lamentably, division and discrimination are still the main emotional considerations on which English is being popularly used as the trolls of the minister’s English usage have shown. It is indeed regrettable that their small-mindedness prevents them from realizing that the Brits have long lost their long undisputed ownership over the English language along with the Empire itself. It is no longer in the hands of the colonial masters. So why allow it to be wielded by a privileged few mired in misplaced notions of elitism?

Features

Finally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

Clandestine visit to Speaker’s residence:

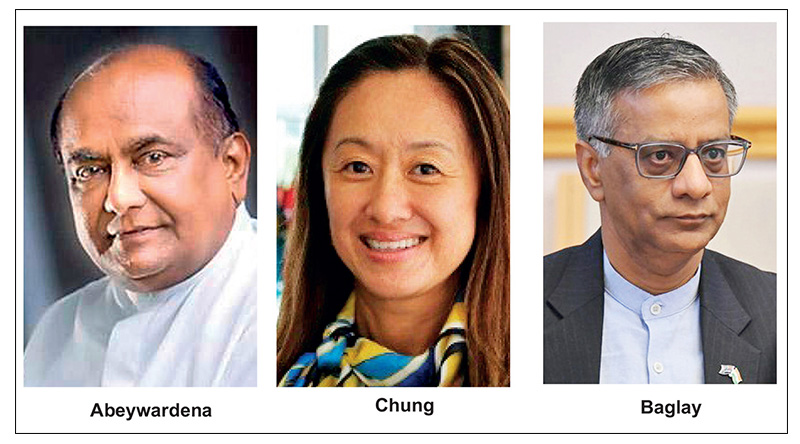

Finally, former Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena has set the record straight with regard to a controversial but never properly investigated bid to swear in him as interim President. Abeywardena has disclosed the circumstances leading to the proposal made by external powers on the morning of 13 July, 2022, amidst a large scale staged protest outside the Speaker’s official residence, situated close to Parliament.

Lastly, the former parliamentarian has revealed that it was then Indian High Commissioner, in Colombo, Gopal Baglay (May 2022 to December 2023) who asked him to accept the presidency immediately. Professor Sunanda Maddumabandara, who served as Senior Advisor (media) to President Ranil Wickremesinghe (July 2022 to September 2024), disclosed Baglay’s direct intervention in his latest work, titled ‘Aragalaye Balaya’ (Power of Aragalaya).

Prof. Maddumabandara quoted Abeywardena as having received a startling assurance that if he agreed to accept the country’s leadership, the situation would be brought under control, within 45 minutes. Baglay had assured Abeywardena that there is absolutely no harm in him succeeding President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, in view of the developing situation.

The author told the writer that only a person who had direct control over the violent protest campaign could have given such an assurance at a time when the whole country was in a flux.

One-time Vice Chancellor of the Kelaniya University, Prof. Maddumabandara, launched ‘Aragalaye Balaya’ at the Sri Lanka Foundation on 20 November. In spite of an invitation extended to former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the ousted leader hadn’t attended the event, though UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe was there. Maybe Gotabaya felt the futility of trying to expose the truth against evil forces ranged against them, who still continue to control the despicable agenda.

Obviously, the author has received the blessings of Abeywardena and Wickremesinghe to disclose a key aspect in the overall project that exploited the growing resentment of the people to engineer change of Sri Lankan leadership.

The declaration of Baglay’s intervention has contradicted claims by National Freedom Front (NFF) leader Wimal Weerawansa (Nine: The hidden story) and award-winning writer Sena Thoradeniya (Galle Face Protest: System change for anarchy) alleged that US Ambassador Julie Chung made that scandalous proposal to Speaker Abeywardena. Weerawansa and Thoradeniya launched their books on 25 April and 05 July, 2023, at the Sri Lanka Foundation and the National Library and Documentation Services Board, Independence Square, respectively. Both slipped in accusing Ambassador Chung of making an abortive bid to replace Gotabaya Rajapaksa with Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena.

Ambassador Chung categorically denied Weerawansa’s allegation soon after the launch of ‘Nine: The hidden story’ but stopped short of indicating that the proposal was made by someone else. Chung had no option but to keep quiet as she couldn’t, in response to Weerawansa’s claim, have disclosed Baglay’s intervention, under any circumstances, as India was then a full collaborator with Western designs here for its share of spoils. Weerawansa, Thoradeniya and Maddumabandara agree that Aragalaya had been a joint US-Indian project and it couldn’t have succeeded without their intervention. Let me reproduce the US Ambassador’s response to Weerawansa, who, at the time of the launch, served as an SLPP lawmaker, having contested the 2020 August parliamentary election on the SLPP ticket.

“I am disappointed that an MP has made baseless allegations and spread outright lies in a book that should be labelled ‘fiction’. For 75 years, the US [and Sri Lanka] have shared commitments to democracy, sovereignty, and prosperity – a partnership and future we continue to build together,” Chung tweeted Wednesday 26 April, evening, 24 hours after Weerawansa’s book launch.

Interestingly, Gotabaya Rajapaksa has been silent on the issue in his memoirs ‘The Conspiracy to oust me from Presidency,’ launched on 07 March, 2024.

What must be noted is that our fake Marxists, now entrenched in power, were all part and parcel of Aragalaya.

A clandestine meeting

Abeywardena should receive the appreciation of all for refusing to accept the offer made by Baglay, on behalf of India and the US. He had the courage to tell Baglay that he couldn’t accept the presidency as such a move violated the Constitution. In our post-independence history, no other politician received such an offer from foreign powers. When Baglay stepped up pressure, Abeywardena explained that he wouldn’t change his decision.

Maddumabandara, based on the observations made by Abeywardena, referred to the Indian High Commissioner entering the Speaker’s Official residence, unannounced, at a time protesters blocked the road leading to the compound. The author raised the possibility of Baglay having been in direct touch with those spearheading the high profile political project.

Clearly Abeywardena hadn’t held back anything. The former Speaker appeared to have responded to those who found fault with him for not responding to allegations, directed at him, by revealing everything to Maddumabandara, whom he described in his address, at the book launch, as a friend for over five decades.

At the time, soon after Baglay’s departure from the Speaker’s official residence, alleged co-conspirators Ven. Omalpe Sobitha, accompanied by Senior Professor of the Sinhala Faculty at the Colombo University, Ven. Agalakada Sirisumana, health sector trade union leader Ravi Kumudesh, and several Catholic priests, arrived at the Speaker’s residence where they repeated the Indian High Commissioner’s offer. Abeywardena repeated his previous response despite Sobitha Thera acting in a threatening manner towards him to accept their dirty offer. Shouldn’t they all be investigated in line with a comprehensive probe?

Ex-President Wickremesinghe with a copy of Aragalaye Balaya he received from its author, Prof. Professor Sunanda Maddumabandara, at the Sri Lanka Foundation recently (pic by Nishan S Priyantha)

On the basis of what Abeywardena had disclosed to him, Maddumabanadara also questioned the circumstances of the deployment of the elite Special Task Force (STF) contingent at the compound. The author asked whether that deployment, without the knowledge of the Speaker, took place with the intervention of Baglay.

Aragalaye Balaya

is a must read for those who are genuinely interested in knowing the unvarnished truth. Whatever the deficiencies and inadequacies on the part of the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration, external powers had engineered a change of government. The writer discussed the issues that had been raised by Prof. Maddumabandara and, in response to one specific query, the author asserted that in spite of India offering support to Gotabaya Rajapaksa earlier to get Ranil Wickremesinghe elected as the President by Parliament to succeed him , the latter didn’t agree with the move. Then both the US and India agreed to bring in the Speaker as the Head of State, at least for an interim period.

If Speaker Abeywardena accepted the offer made by India, on behalf of those backing the dastardly US backed project, the country could have experienced far reaching changes and the last presidential election may not have been held in September, 2004.

After the conclusion of his extraordinary assignment in Colombo, Baglay received appointment as New Delhi’s HC in Canberra. Before Colombo, Baglay served in Indian missions in Ukraine, Russia, the United Kingdom, Nepal and Pakistan (as Deputy High Commissioner).

Baglay served in New Delhi, in the office of the Prime Minister of India, and in the Ministry of External Affairs as its spokesperson, and in various other positions related to India’s ties with her neighbours, Europe and multilateral organisations.

Wouldn’t it be interesting to examine who deceived Weerawansa and Thoradeniya who identified US Ambassador Chung as the secret visitor to the Speaker’s residence. Her high-profile role in support of the project throughout the period 31 March to end of July, 2022, obviously made her an attractive target but the fact remains it was Baglay who brought pressure on the then Speaker. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena’s clarification has given a new twist to “Aragalaya’ and India’s diabolical role.

Absence of investigations

Sri Lanka never really wanted to probe the foreign backed political plot to seize power by extra-parliamentary means. Although some incidents had been investigated, the powers that be ensured that the overall project remained uninvestigated. In fact, Baglay’s name was never mentioned regarding the developments, directly or indirectly, linked to the devious political project. If not for Prof. Maddumabandara taking trouble to deal with the contentious issue of regime change, Baglay’s role may never have come to light. Ambassador Chung would have remained the target of all those who found fault with US interventions. Let me be clear, the revelation of Baglay’s clandestine meeting with the Speaker didn’t dilute the role played by the US in Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s removal.

If Prof. Maddumabandara propagated lies, both the author and Abeywardana should be appropriately dealt with. Aragalaye Balaya failed to receive the desired or anticipated public attention. Those who issue media statements at the drop of a hat conveniently refrained from commenting on the Indian role. Even Abeywardena remained silent though he could have at least set the record straight after Ambassador Chung was accused of secretly meeting the Speaker. Abeywardena could have leaked the information through media close to him. Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Ranil Wickremesinghe, too, could have done the same but all decided against revealing the truth.

A proper investigation should cover the period beginning with the declaration made by Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s government, in April 2022, regarding the unilateral decision to suspend debt repayment. But attention should be paid to the failure on the part of the government to decide against seeking assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to overcome the crisis. Those who pushed Gotabaya Rajapaksa to adopt, what they called, a domestic solution to the crisis created the environment for the ultimate collapse that paved the way for external interventions. Quite large and generous Indian assistance provided to Sri Lanka at that time should be examined against the backdrop of a larger frightening picture. In other words, India was literally running with the sheep while hunting with the hounds. Whatever the criticism directed at India over its role in regime change operation, prompt, massive and unprecedented post-Cyclone Ditwah assistance, provided by New Delhi, saved Sri Lanka. Rapid Indian response made a huge impact on Sri Lanka’s overall response after having failed to act on a specific 12 November weather alert.

It would be pertinent to mention that all governments, and the useless Parliament, never wanted the public to know the truth regarding regime change project. Prof. Maddumabandara discussed the role played by vital sections of the armed forces, lawyers and the media in the overall project that facilitated external operations to force Gotabaya Rajapaksa out of office. The author failed to question Wickremesinghe’s failure to launch a comprehensive investigation, with the backing of the SLPP, immediately after he received appointment as the President. There seems to be a tacit understanding between Wickremesinghe and the SLPP that elected him as the President not to initiate an investigation. Ideally, political parties represented in Parliament should have formed a Special Parliamentary Select Committee (PSC) to investigate the developments during 2019 to the end of 2022. Those who had moved court against the destruction of their property, during the May 2022 violence directed at the SLPP, quietly withdrew that case on the promise of a fresh comprehensive investigation. This assurance given by the Wickremesinghe government was meant to bring an end to the judicial process.

When the writer raised the need to investigate external interventions, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) sidestepped the issue. Shame on the so-called independent commission, which shows it is anything but independent.

Sumanthiran’s proposal

Since the eradication of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in May 2009, the now defunct Tamil National Alliance’s (TNA) priority had been convincing successive governments to withdraw the armed forces/ substantially reduce their strength in the Northern and Eastern Provinces. The Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi (ITAK)-led TNA, as well as other Tamil political parties, Western powers, civil society, Tamil groups, based overseas, wanted the armed forces out of the N and E regions.

Abeywardena also revealed how the then ITAK lawmaker, M.A. Sumanthiran, during a tense meeting chaired by him, in Parliament, also on 13 July, 2022, proposed the withdrawal of the armed forces from the N and E for redeployment in Colombo. The author, without hesitation, alleged that the lawmaker was taking advantage of the situation to achieve their longstanding wish. The then Speaker also disclosed that Chief Opposition Whip Lakshman Kiriella and other party leaders leaving the meeting as soon as the armed forces reported the protesters smashing the first line of defence established to protect the Parliament. However, leaders of minority parties had remained unruffled as the situation continued to deteriorate and external powers stepped up efforts to get rid of both Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Ranil Wickremesinghe to pave the way for an administration loyal and subservient to them. Foreign powers seemed to have been convinced that Speaker Abeywardena was the best person to run the country, the way they wanted, or till the Aragalaya mob captured the House.

The Author referred to the role played by the media, including social media platforms, to promote Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s successor. Maddumamabandara referred to the Hindustan Times coverage to emphasise the despicable role played by a section of the media to manipulate the rapid developments that were taking place. The author also dealt with the role played by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) in the project with the focus on how that party intensified its actions immediately after Gotabaya Rajapaksa stepped down.

Disputed assessment

The Author identified Ministers Bimal Rathnayaka, Sunil Handunetti and K.D. Lal Kantha as the persons who spearheaded the JVP bid to seize control of Parliament. Maddumabanda unflinchingly compared the operation, mounted against Gotabaya Rajapaksa, with the regime change operations carried out in Iraq, Libya, Egypt and Ukraine. Asserting that governments loyal to the US-led Western block had been installed in those countries, the author seemed to have wrongly assumed that external powers failed to succeed in Sri Lanka (pages 109 and 110). That assertion is utterly wrong. Perhaps, the author for some unexplained reasons accepted what took place here. Nothing can be further from the truth than the regime change operation failed (page 110) due to the actions of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana and Ranil Wickremesinghe. In case, the author goes for a second print, he should seriously consider making appropriate corrections as the current dispensation pursues an agenda in consultation with the US and India.

The signing of seven Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with India, including one on defence, and growing political-defence-economic ties with the US, have underscored that the JVP-led National People’s Power (NPP) may not have been the first choice of the US-India combine but it is certainly acceptable to them now.

The bottom line is that a democratically elected President, and government, had been ousted through unconstitutional means and Sri Lanka meekly accepted that situation without protest. In retrospect, the political party system here has been subverted and changed to such an extent, irreparable damage has been caused to public confidence. External powers have proved that Sri Lanka can be influenced at every level, without exception, and the 2022 ‘Aragalaya’ is a case in point. The country is in such a pathetic state, political parties represented in Parliament and those waiting for an opportunity to enter the House somehow at any cost remain vulnerable to external designs and influence.

Cyclone Ditwah has worsened the situation. The country has been further weakened with no hope of early recovery. Although the death toll is much smaller compared to that of the 2004 tsunami, economic devastation is massive and possibly irreversible and irreparable.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Catastrophic Impact of Tropical Cyclone Ditwah on Sri Lanka: