Features

Rescuing Sri Lankan history: Reflections on the past

By Uditha Devapriya

In his influential essay “The People of the Lion”, R. A. L. H. Gunawardana argues for a national historiography, devoid of Western ideology. He does not refute or call for the doing away of such ideology altogether, but suggests rather that it has intruded on studies of group identities to such an extent that the history we think we unearth is very different to the history that may actually have prevailed.

Thus, by imputing terms like “race” (a term originating in 16th century Europe) and “Aryan” (which gained prominence with attempts by Orientalist scholars to draw parallels between Indo-Lankan and European languages), we are, as he points out, “presenting a view of the past moulded by contemporary ideology.” If this is the case, which I personally think it must be, then what is the history we have and the history we must talk of?

What we know, from the inscriptions, the chronicles, and the reconstructed narratives, is that Sri Lankan society was never really rooted in the concept of race as it is today. Group ideology was determined by tribes that migrated from other societies. The first hunter-gatherers lacked iron implements, which is how they came to be assimilated by Indo-Aryan Iron Age settlers. While these hunter-gatherers are said to have approximated to Veddhas, the later Iron Age settlers are said to have approximated to Sinhala people.

The question of whether hunter-gatherers formed an agricultural group is debated: the Valahassa Jatakaya, for instance, tells us of she-yakkas devouring food from wrecked ships and enslaving, if not tormenting, the sailors aboard them, while the Mahavamsa relates an episode of Vijaya coming across these ships after his encounter with Kuveni. Fa-Hsien was, as K. M. de Silva observes, not being very helpful in these matters when he wrote that the country had been originally inhabited by yaksas and nagas who traded with merchants, simply because human settlements predated both those clans.

Such narratives divided not just scholars, but also littérateurs: Martin Wickramasinghe in Sinhala Sahithyaye Nageema argued that the existence of such ships showed the absence of an advanced pre-Vijayan agricultural society, while the pioneers of the Hela Havula stated that Kuveni having engaged herself with a spinning wheel at the time of Vijaya’s entrance showed that society had been advanced prior to Indo-Aryan colonisation.

The issue is that these texts were occupied more with idealising a religious or dynastic sect than with presenting a view of life as it was lived. If they presented such a view, which they occasionally did, they did so in a hazy, amorphous way. This requires us to turn to hard evidence, etched in stone and recorded for posterity.

The Brahmi inscriptions form arguably the most concrete evidence we have for the civilisation which developed, grew, and flourished after the Indo-Aryan migration. These inscriptions come to us from very early on, and they were made by the upper classes of their time. We have Yaksha, Naga, Vedic, and Puranic inscriptions, and they allude to the status of their authors, their families, and their occupations.

The Puranic inscriptions tell us of pre-Buddhist religious cults which revolved around the Mother Goddess, Vishnu, and Siva, a point that lends credence to G. P. Malalasekara’s view that Vijaya was tolerant of all faiths. Evidence from the inscriptions of Jain and Tamil settlements, as well as settlements by, inter alia, Kabojas (Kashmiris), Moriyas (Mauryas), and Baratas (merchants, or nobles according to Paranavitana) tells us that we were a multiracial country, at least in terms of “contemporary ideology.”

But these clans were so disparate that they found it hard to develop a cohesive identity. They identified themselves by a totem: Moriyas with the peacock, Lambakannas the hare, Kulingas the shrike, and Tarachchas the hyena. This continued into the evolution of group identities later, as evidenced by the use of the lion and the tiger: the former became the standard of the “Sinhala” people, whereas the latter was adopted by the Nayakkar kings of Kandy who ruled over those same “Sinhala” people.

Not surprisingly, in medieval Sri Lankan society the ideology of the ruling class became the identity of the State. What this meant was that there was no overriding racial consciousness of the sort we discern today, so much so that, for instance, when Dutugemunu went to war we had, not Sinhalas fighting Tamils, but one dynasty battling another.

“Sinhala Buddhism”

was probably not rooted in society the way it is now, and if it was, the needs of the sasana would have been considered more important than ethno-nationalist considerations: the author of the Mahavamsa, after all, has Dutugemunu say he’s fighting “not for the joy of sovereignty”, but for the preservation of the Order.

The vague position Buddhism occupied at this juncture can be gleaned from the fact that it was accorded a foremost status even by invading forces, at least in the case of Elara; the Mahavamsa valorises him as a just ruler, tainted only by his “false beliefs.” In contrast, after the 10th century we see a heightening of anti-Buddhist and anti-Jain sentiment among South Indian invaders, which in turn produces a backlash on Sri Lankan soil.

In an otherwise eloquent essay on the subject (“Buddhism, Identity, and Conflict”), H. L. Seneviratne contends that Sri Lankan society was never the ekeeya rajya it is touted as by ultra-nationalists. He is theoretically correct, yet there is an important caveat that must be inserted: that the Westphalian notion of sovereignty was alien to the rulers of the land and thus not totally applicable, at least not to the extent it is today.

To be sure, “particularism” persisted in Anuradhapura, and the absence of a proper central administration in Polonnaruwa contributed to the disintegration of the rajya, denuding it of any ekeeya pretensions. Yet, at the same time, group consciousness permeated society even at the level of a divided State. That is why regional polities tended to band together in the face of military incursions from India, and why the absorption of those polities into a central State in Polonnaruwa under Parakramabahu I deprived the Sinhala kingdom of a viable base from which it could strategise counter-campaigns against such incursions.

In the aftermath of Kalinga Magha’s military campaigns during the Polonnaruwa era, we see a strengthening of a local Buddhist identity in response to the threat of fragmentation of the State, ekeeya or otherwise. It was a classic case of hostility by an invading force giving rise to a group identity on the invaded terrain. Nissanka Malla’s decree that only a Buddhist could rule the land hence must be seen in the light of Magha’s later campaigns of destruction. The fact that this “Buddhist king” himself is said to have originated from the Kalinga line speaks volumes about the amorphous nature of group identity formation.

To be sure, there was opposition to an ethnic Other occupying the throne, but we must understand that it was never the kind of opposition ultra-nationalists project towards the prospect of an ethnic Other presiding over Sri Lanka today.

When Bhuvanekabahu VI faced an uprising in the south, for instance, it was later painted as an uprising against a ruler of Malayali blood; this did not stop chroniclers from celebrating him for his conquest of Jaffna. The case of Waththimi Kumaraya is also significant: while the records are unclear, what we have is an account of a Muslim pretender being killed by a group of nobles, only to be venerated later by Muslims and Buddhists – the latter of whom worship him as Gale Bandara Deviyo. The level of ignorance displayed by ultra-nationalists to such subtle nuances of history surfaced years ago when, after I noted that Gale Bandara Deviyo may have had Muslim origins, a young lad of 19 protested his origins and suggested to me that, because he was non-Buddhist, he should not be venerated!

We see such ambiguities in the Kandyan era as well. However, despite Gunawardana’s assertion that uprisings by the aristocracy against rulers were a common occurrence even prior to the advent of Nayakkar rule, we must admit that such uprisings became more and more common after the installation of the Nayakkar line on the throne.

The contrast between the Ingirisihatana and the Vadigahatana must be considered in this light: the former celebrated Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe for his victory over the British in 1803, while the latter was written by Kavisundara Mudali, a confidante of Eheliyapola Adikaram who was antagonistic towards the king, following the annexation of 1815.

If that sounds strange, consider that the writers of historical chronicles have always, since the time of the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa, tilted in favour of one group over another. That is why we see a great deal of Dutugemunu, and so little of Mahasen, who Mahanama Thera seems to have mentioned, if at all, for his efforts at developing the irrigation system of the land. Curious as such paradoxes may be, they survived well into the British era, when the continuation of the Mahavamsa depicted the British as heroic, even though the author, Yagirala Pannananda, received no proper backing from the State.

In any case, it’s one of the biggest ironies of history that the Vadigahatana and the Kirala Sandeshaya called out on the wickedness of Sri Wickrama Rajasinghe by identifying himself with an ethnic Other, when the Nayakkar line had been chosen after the death of Vira Parakrama Narendrasinghe to head the country because there had been no Sinhalese of kshatriya blood (a sine qua non of kinship in the post-Nissanka Malla era) available; certain nobles had wanted Unamboowe, but he was not “pure”.

It is also ironic that each and every anti-British uprising after 1815 required a Nayakkar pretender; the exception, after which no Nayakkars reclaimed the fight, was 1848. Such facets have long been forgotten by those who insert contemporary ideology into the past: perhaps the most grievous error we can commit, not just to history, but to our history. To rescue that history thus requires a radical re-evaluation of our past.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

Why are SL universities’ positions low in world ranking indices?

Arespected law firm in New Zealand, when advertising positions for apprentice lawyers, tends to overlook applications from graduates who have not attended top-ranked institutions. Hence, it becomes crucial for universities to achieve international high rankings. Beyond scenarios like job searches, there are several reasons why a higher ranking holds significance for a university:

Arespected law firm in New Zealand, when advertising positions for apprentice lawyers, tends to overlook applications from graduates who have not attended top-ranked institutions. Hence, it becomes crucial for universities to achieve international high rankings. Beyond scenarios like job searches, there are several reasons why a higher ranking holds significance for a university:

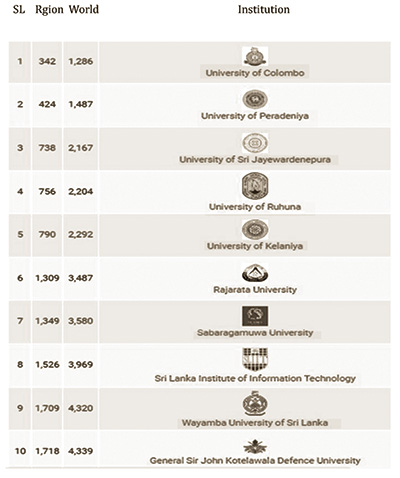

https://www.adscientificindex.com/university-ranking/?funding=All+Universities&country_code=lk

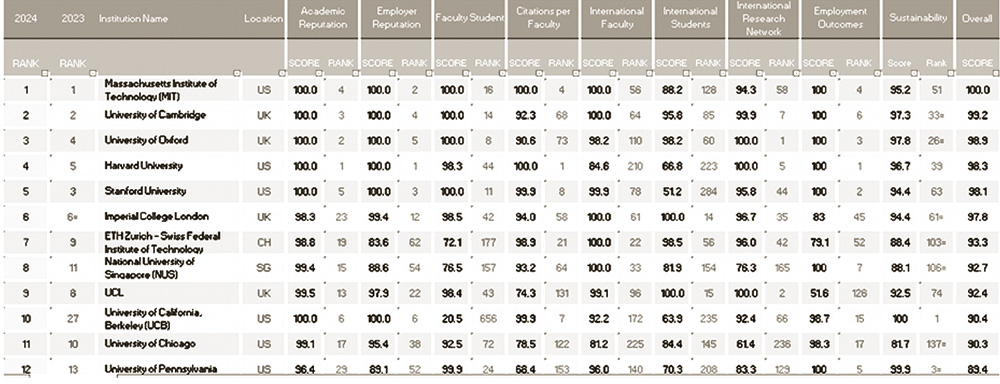

Source: https://www.topuniversities.com/world-university-rankings

Prestige, Reputation and Research

A higher rank enhances the prestige and reputation of a university both nationally and internationally. It signifies academic excellence, research prowess, and overall institutional quality, attracting top students, faculty, and researchers. A higher rank provides global recognition and visibility to the university, positioning it as a leader in higher education and research. This recognition opens doors to international collaborations, partnerships, and exchange programmes, enriching the academic and cultural experiences of students and faculty.

Higher-ranked universities tend to have greater research impact and influence. They attract top researchers, secure more research funding, and produce groundbreaking discoveries and innovations that address societal challenges and drive economic growth.

Competitiveness and Attracting Talents

A higher rank increases the competitiveness of the university in attracting funding, grants, and partnerships. Funding agencies, philanthropic organisations, and industry partners are more likely to collaborate with highly ranked universities, leading to increased opportunities for research, innovation, and economic development.

Universities with higher ranks are more attractive to talented students, faculty, and researchers. Top-ranked universities can recruit and retain the best minds in academia, fostering a vibrant intellectual community and facilitating knowledge creation and dissemination.

Higher-ranked universities typically experience higher student enrollment and retention rates. Students are drawn to universities with strong academic reputations, diverse programme offerings, and attractive campus environments, enhancing the university’s revenue and sustainability.

The reputation and network of a higher-ranked university can positively impact the career prospects and success of its alumni. Graduates from prestigious universities often have access to better job opportunities, higher salaries, and influential professional networks, contributing to their long-term success and the reputation of the university.

Overall, a higher rank serves as a symbol of excellence, attracting talent, resources, and opportunities that contribute to the continued success and advancement of the university. The tables provide global rankings of universities, as well as rankings specific to the South Asian region and Sri Lanka.

Overall, a higher rank serves as a symbol of excellence, attracting talent, resources, and opportunities that contribute to the continued success and advancement of the university. The tables provide global rankings of universities, as well as rankings specific to the South Asian region and Sri Lanka.

Several factors contribute to Sri Lankan universities being ranked low:

Quality of Education and Research: Some Sri Lankan universities struggle to maintain high standards of education and research due to factors such as outdated curricula, inadequate teaching resources, and limited access to modern technologies and learning materials.

Low levels of research output and innovation contribute to the low rankings of Sri Lankan universities. Factors such as limited research funding, inadequate research infrastructure, and a lack of incentives for faculty to engage in research can hinder the production of high-quality research outputs.

Faculty Quality and funding: The quality and professional development of faculty members play a significant role in the rankings of universities. Challenges such as brain drain, where talented academics seek opportunities abroad due to better prospects, and limited opportunities for faculty development and training can impact the quality of teaching and research. Issues related to governance and management, including bureaucratic inefficiencies, lack of transparency, and political interference, can affect the overall functioning and performance of universities.

Sri Lankan universities often face challenges due to limited funding and investment in higher education. Insufficient financial resources can impact infrastructure development, research facilities, faculty recruitment, and student support services. Inadequate infrastructure and facilities, including outdated laboratories, libraries, and IT infrastructure, can hinder the ability of universities to provide quality education and conduct impactful research.

International Collaboration and Recognition: Limited international collaboration and recognition can also contribute to the low rankings of Sri Lankan universities. Engaging in partnerships with international institutions, participating in global research networks, and obtaining accreditation from reputable international organizations can enhance the visibility and reputation of universities.

The role of university administration

The factor of governance and management plays a significant role in influencing the encouragement or discouragement of research publication in quality journals indexed in databases like Scopus or Web of Science.

However, there seems to be a prevailing trend of publishing solely for the sake of meeting publication quotas in local journals that lack indexing, primarily to accumulate points for career advancement purposes.

Bureaucratic Inefficiencies: Inefficient bureaucratic processes within universities can create barriers and delays in the research publication process. For instance, complex administrative procedures for obtaining approvals such as ethical approval, funding, or accessing resources can discourage faculty members from pursuing research or submitting their work to quality indexed international journals. The time and effort required to navigate bureaucratic red tape may outweigh the benefits of publishing prestigious journals.

Lack of Transparency: Universities that lack transparency in their governance and decision-making processes may create an environment where researchers feel uncertain or insecure about the publication process. Without clear guidelines, criteria, and expectations for research publication, faculty members may hesitate to invest time and resources in producing high-quality research or submitting it to reputable journals. Additionally, concerns about favoritism, bias, or arbitrary decision-making in the publication process can undermine trust and confidence among researchers.

Political Interference: Political interference in university governance can have detrimental effects on research culture and academic freedom. When political agendas influence decision-making related to research priorities, funding allocation, or editorial policies, it may compromise the integrity and independence of academic research. Researchers may feel pressured to align their work with political interests or avoid controversial topics that could jeopardize their careers or funding opportunities. In such environments, there may be a tendency to prioritize quantity over quality in research output, with less emphasis on publishing in prestigious journals indexed in databases like Scopus or Web of Science.

Role of the Ministry of Education and the University Grant Commission

The University Grants Commission (UGC) serves as the governing authority for the university system in Sri Lanka, guided by nicely crafted vision, mission, and goals as per their website; https://www.ugc.ac.lk/

The absence of goals focused on “high impact research,” as outlined in the mission statement, highlights a potential gap in the UGC’s initiatives. This oversight may contribute to the lack of emphasis on promoting research publication in high-quality international journals, which is crucial for achieving higher ranks in ranking indices.

Further, in the promotion process for academics to the positions of Associate Professors and Professors, the University Grants Commission (UGC) has issued circulars outlining a point system; UGC Circular No. 723 of 12 December 1997, 869 of 30 November 2005, and 916 of 30 September 2009.

According to these circulars, a senior lecturer in the university system must accumulate 105 points to qualify for the Professor position, with a minimum of 55 points required from Research and Creative work. However, the conditions for claiming these points are relatively lax, requiring only that publications appear in numbered volumes and pass peer review. While there are no restrictions on maximum points, a critical issue remains: there is no minimum requirement for points articles published in globally recognized indexed journals.

Consequently, some faculties of certain universities resort to publishing their own “journals” and organizing “international conferences” to claim points without conducting rigorous research or publishing them in internationally reputed indexed databases.

Crucially, there should be a cap on the maximum points awarded for local publications, even if they are published by “recognized publishers,” a term not clearly defined in the circular. Publishers like Sarasavi, Vijitha, and Gunasena are well-known, yet citations from their publications are not acknowledged by WoS, Scopus or Google, thus not factored into rankings by agencies.

The Way out.

To boost Sri Lankan universities in global rankings, the UGC and Ministry of Education should revise their missions and goals to include more research and internationally recognized indexed publications for universities and ensure clear communication to prospective university staff.

Staff should receive more than just recognition for publications, with rewards such as cash incentives and public appreciation. Making research projects compulsory for undergraduates, postgraduates, and masters, and incentivizing manuscript submissions with marks or cash rewards, could further motivate students.

Conclusions

Overall, addressing issues related to governance and management is essential for fostering a conducive environment for research publication in quality indexed journals. Universities need to streamline administrative processes, enhance transparency in decision-making, and safeguard academic freedom from political interference. By promoting a culture of excellence, integrity, and meritocracy, universities can encourage faculty members to actively engage in research and contribute to knowledge dissemination through publications in reputable indexed journals.

Addressing these challenges requires concerted efforts from various stakeholders, including government authorities, university administrations, faculty members, students, and funding agencies. To elevate Sri Lankan universities in global rankings, the UGC and Ministry of Education should update their missions to prioritize research and internationally recognized publications. Additionally, staff should be rewarded beyond recognition, with incentives like cash rewards and public appreciation. Implementing compulsory research projects and incentivizing manuscript submissions can enhance student motivation at all academic levels.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT University, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

Revival of Premadasaism: Way forward for Sri Lanka

By Dr. Mahim Mendis

Sri Lanka President’s Scholar, British Chevening Scholar, National University of Singapore Scholar and US State Department Post Doctoral Scholar

I was socialised in my childhood by an ardent Samasamajist father in Moratuwa. However, I became disillusioned in my youth, as I witnessed the ground level actions of the Samasamaja Party, working with Feudalists who pretended to be progressive.

I was not surprised when the LSSP was rejected by voters in the 1977 election. The void created in me was filled by Vijaya Kumaranatunge, when he formed the Mahajana Party with a principled position on social justice. When the JVP brutally murdered Vijaya in 1987, my hopes were dashed.

By the time I entered Kelaniya University, I was becoming a convert to ‘Premadasaism’ – the deep convictions found in the words and deeds of Ranasinghe Premadasa that I diligently followed.

I was mesmerised by the speeches of Premadasa, who articulated his pro-poor ideology of the UNP, the party, that my father opposed all his life. Today, I am convinced that Sri Lanka is fortunate that Premadasa has left for this nation a son named Sajith, who is inspired by Premadasa’s ideology and his simple lifestyle.

Pragmatic and Practical

While academics continue to talk about grand development theory, Ranasinghe Premadasa spent his life evolving a truly Sri Lankan development model to ensure and enable common people to reach excellence in all sectors of human development.

Youth of the land should not forget that Premadasa had the foresight to build the first ever, Day and Night Cricket Stadium, at Kettarama, long before we won the World Cup in 1996 and transformed Sugathadasa Stadium in line with top international benchmarks, encouraging younger athletes to reach excellence at the Olympics. He believed that Damayanthi Darsha, the South Asian Games Gold medalist should access the best schools of the land, paving the way for her to be educated at Ladies College, Colombo. He was impatient to see the bright rural youth shine unlike feudal politicians who preached one thing to the people and practiced another for their own children.

To serve the needs of common people, he established the Sevana Sarana Foster Parents scheme, to provide for the material needs of children. For this he mobilised the affluent to be socially sensitive to the bright, but poor children.

Today, it is not surprising to see his son Sajith inspired to do all this even before he forms a government.

Birth of Premadasaism

Premadasa harboured these grand ideals of Pro-People Development when he was a child of 15 years of age. He established the Sucharitha Movement in his own habitat Keselwatta, in the Colombo Central electorate.

Premadasa’s vision was far beyond Marxism of Kueneman or Communist Trade Unionism of L. W Panditha and the Temperance policies of F.R. Senanayake. He saw the beauty of holistic human development, balancing physical and material self-sufficiency of people with spiritual, emotional, and cultural self-sufficiency. He knew clearly that building a ‘Total Man’, would contribute towards a holistic ‘Total Society.’

As a social worker at the early age of fifteen, he celebrated the First Anniversary of the Sucharitha Movement with S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike and Mrs. Bandaranaike as Chief Guests, long before Bandaranaike ever thought of forming the SLFP.

Having entered politics in his youth under the tutelage of the eminent Labour leader A. E. Goonesinghe, Premadasa realised just as his political guru Goonesinghe realised, that Marxist inspired politicians coming from affluent backgrounds had severe limitations in their capacities as they were overwhelmed by their own unparalleled revolutionary rhetoric that made them lag in actions.

Premadasa would turn in his grave if he heard the emotionally and spiritually sterile NPP/Marxist rhetoric of today that husbands should remunerate their wives for their domestic labour.

Communicating Revolutionary Ideas in a Language Common Man Understood

Premadasa soon became the Youth Front Leader of AE Gunasinghe’s Labour Party and was able to explain about social emancipation to the common people- what Marxists like Peter Kuenemann in Central Colombo or Dr. N. M Perera of Ruwanwella could not explain in lingo understood by the poor.

When Premadasa opted to join the UNP, its leader Dudley Senanayake had the wisdom to appreciate this capacity, pitting young Premadasa against Dr. N. M Perera in Dr. Perera’s own electorate Ruwanwella, at the 1956 Parliamentary elections.

The election proved that the Marxist giant Dr. Perera could defeat young Premadasa, only by a margin of mere 6,228 votes.

Ironically ten years later, Dr Peter Kueneman, Dr. Colvin R. De Silva, Dr. S. A. Wickramasinghe and the other LSSP and Communist Party Parliamentary stalwarts had to retire from Parliamentary politics when they were politically annihilated by the UNP campaign that was led by the same Premadasa who was Deputy Leader of the UNP at the 1977 Parliamentary elections.

Humility of Premadasa and Arrogance of Distractors

President Premadasa was an extraordinary leader with a broad imagination. He was prepared to embrace Oxford educated Susil Siriwardena, a former Theoretician of the JVP, and listen to Wijeweera, attending conscientiously the proceedings of the Criminal Justice Commission in the aftermath of the First JVP uprising in 1971.

He extended his hand of friendship to them with conviction. However, Wijeweera was not prepared. Susil, who was a JVP theoretician, was wiser in correctly perceiving the mind of Premadasa.

The difference between Premadasa and Wijeweera, as my respected friend Dr. Dayan Jayatilleke makes clear is that unlike Wijeweera, Premadasa saw no place for violence in social system change as violence would have to be suppressed by the State at a severe cost to the very people whom they tried to emancipate. Ironically, JVP failed to appreciate this, due to arrogance on their part as stated by Dr. Jayatilleke in a recent interview with Kusum Wijetilleke- a trait that they still have not shed due to the inherent tendency to overestimate themselves.

In the late 1980’s, Premadasa appointed the National Commission on Youth Unrest, chaired by Professor G. L. Peiris, who made serious recommendations such as meritocracy, based employment and youth participation in politics.

Professor Peiris, who was appointed Vice Chancellor of Colombo University by President Premadasa, and Founder Chair of Pohottuwa, recently opted to join with Sajith Premadasa as he was convinced that Sajith.

Premadasa’s as a Champion of Inclusive Development

The 1978 Constitution purposefully alienated anti-establishment as well as ethnic minority parties from being represented in parliament. For this, JR Jayewardene’s Constitution had a purposeful, but unrealistic cut off point of 12 % in electoral performance for representation.

The present-day JVP should appreciate that Premadasa not only released more than 1,000 JVP activists when he came to power but brought down the cut off point for representation to 5%. Today, the JVP is represented in parliament, together with ethnic minority parties which continue to advocate shared political power.

While progressive Sri Lankans appreciate these social democratic political reforms, the very beneficiaries of these policies may not appreciate what Premadasa achieved for them with his powerful ethos of inclusive, value centered development for the common good of all Sri Lankans. However, many people will remember him as a genuine seeker of a new Social Contract.

Knowing Difference Between Extreme Capitalism and Extreme Socialism

Truly, cultured men and women have the capacity to be thankful for the progressive measures taken by Ranasinghe Premadasa. He was a true embodiment of social democracy, governing the entire social, political, cultural, and moral order. He was not a mere propagator of a social market economy, when he took over leadership from a right wing, J.R. Jayewardene led the UNP that tried to deprive Deputy Leader Premadasa of his well-earned presidential candidature in 1989. The same right-wing forces in the UNP, tried to impeach him together with Feudalist sympathizers, who lost all their social status due to Premadasaism

Cost of Disowning Premadasa Programme and Vision

Ironically, the so-called educated people of the land, who were found guilty of bankrupting the Sri Lankan economy are among those who disowned the Premadasa legacy that brought recognition, human dignity, and prosperity to our people.

As emphasised by world renowned social scientist, Dr. Howard Nicholas in an interview with Kusum Wijetilleke, his pessimism about Sri Lanka, turned into great optimism in late 1980s with the pro-people contribution of Ranasinghe Premadasa. This, as he says, was a time Sri Lanka was in a perilous condition with a total breakdown of institutions, aggravated by JVP and LTTE terrorism.

Promise for the Future: The Need for a Likeminded Leader

We need a visionary leader with the right mindset with a heart for the poor and for those who can generate wealth and transform Sri Lanka. We know that the options are very few. The heart and the mind of Premadasa is what is absent in the very people that Premadasa groomed for leadership, including the current President, Ranil Wickramasinghe.

Today, the only hope we see for our nation is Sajth Premadasa; Premadasa’s son who has the courage and foresight to commence an unprecedented Social Democratic programme.

Ranasinghe Premadasa, expounding his grand development vision as far back as 04 April, 1973, stated:

“Political power has been diffused amongst the people through the exercise of the franchise. In like manner, the economic wealth of the country should also be diffused amongst the people. We should evolve a scheme under which the public sector, the co-operative sector, the private sector, and a combination of all these three sectors – a joint sector – could function in competition with each other. Such competition will bring the maximum benefit to the people who need not become slaves of either a public or private monopoly. The government should ensure through its legislative and planning processes that the people participate in all aspects of development without allowing monopolies — state or individual.”

As a petitioner of the historic Supreme Court Case, in 2022, on bankrupting of the economy, which led to a historic verdict in favour of our petition, I would not have been moved to file action on behalf of the country’s entire citizenry, if not for my respect for the Premadasa ideology, which is continued and adapted to meet the challenges of modern Sri Lanka by his son, Sajith Premadasa.

Features

No escape from international human rights scrutiny

by Jehan Perera

In March 2020, the Sri Lankan government believed that the massive mandate President Gotabaya Rajapaksa had received gave it a licence to get out of the cycle of UN Human Rights Council resolutions by unilaterally opting out of the process. It announced that it would no longer consider itself bound to implement the resolution in force at that time. It stated its position was “backed by a people’s mandate and is in the interest of Sri Lanka and its people, instead of opting to continue with a framework driven externally that has failed to deliver genuine reconciliation for over four and half years.” However, the government also sought to keep itself within the framework of the UN system. The government stated that within a new framework of national reconciliation it was proposing it would continue to welcome the visits, advice and technical support from the UN system.

The re-emergence of the Easter Sunday bombing of 2019 into the mainstream of political debate is bound to have both domestic and international political consequences. Presidential elections are scheduled for October the latest. The UN Human Rights Council will meet in Geneva in September. The role played by Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith who gives leadership to the Catholic Church in the country is proving to be important in both. He has openly accused the government of being unresponsive to their search for the truth and justice. He complained that he and other members of the church had addressed a letter to the president “calling for a fresh and independent investigation into these attacks, but not even a letter of acknowledgement was sent to us.”

In a recent media interview, Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith stated that two political parties had met him and submitted their proposals for investigations of the Easter bombing if they win the forthcoming elections. The Cardinal has called upon those in his church not to vote for parties that have failed to make a commitment to truth and justice and presented concrete plans regarding this. The implications of this will have a bearing on the Catholic vote at the forthcoming elections. In addition, the Cardinal has announced that the Catholic Church is planning to present a proposal to the UNHRC. This is likely to have a detrimental effect on the government’s plan to extricate itself from the UNHRC process in Geneva.

OTHER CONFLICTS

The previous government’s bid to extricate itself from the UNHRC resolution by the strategy of unilateral withdrawal was not successful. Instead it led to a stronger resolution being passed the next time around which set up a special monitoring mechanism in Geneva to collect and safeguard evidence of human rights violations in Sri Lanka. This is especially worrisome to those in the government, especially those who can be accused of having violated human rights, as it opens the door to prosecution by any government or individual who files a case in an international court that accepts the principle of universal jurisdiction.

President Wickremesinghe is generally believed to have a special relationship with the international community and particularly with those Western countries that give special attention to international human rights. There has been considerable media coverage of his easy familiarity with heads of states at international conferences where the top leaders of the world fraternize with each other and with him. His latest achievement was in welcoming the President of Iran to Sri Lanka as a state guest at a time when the world is on tenterhooks due to Iran’s open clash with Israel which is backed by the Western world. The state media reported that “As in other countries, many people in Sri Lanka thought that the Iranian President Dr. Ibrahim Raisi would cancel the visit at the last minute. The current issue with the West is the proximate cause of this. But it is President Ranil Wickremesinghe who is leading Sri Lanka on a Non-Aligned path without angering the West and without angering the neighbour.”

There is a further reason for believing that Sri Lanka might be able to surmount the challenge of the UNHRC at the present time. This is due to the change in the international environment in which the Israel-Palestine conflict has taken a special place with the intensity of violence in Gaza exceeding that of Ukraine. These are both ongoing conflicts which ought to take priority in contrast to the Sri Lankan conflict which ended 15 years ago. Unlike Ukraine and Gaza, Sri Lanka is today a country without large-scale violence. Indeed, it is remarkable that there has not been a single incident of large-scale violence after the end of the war except for the mystery of the Easter bombing to which answers are not being found.

HIDDEN SUFFERING

International tourist guide books have selected Sri Lanka as the safest country in the world for a single woman to travel through on account of warmth and civility of the people and, of course, a well-functioning security system. In addition, where the post-war situation is concerned, the government is able to show a plethora of state mechanisms, ranging from multiple commissions of inquiry, the Office on Missing Persons, the Office of Reparations and most recently a Commission for Truth, Unity and Reconciliation which will be established soon. On the other hand, though Sri Lanka is at peace and able to offer a standard of hospitality that is seeing a boom in tourist arrivals, there is pain and suffering inside the society that needs to be taken care of and not neglected.

The largest scale of pain and suffering is due to the economic deprivation that suddenly hit people who were making ends meet, but who have found for the past two years that prices have tripled whilst their salaries remain the same. The World Bank’s most recent study on the impact of the economic collapse states that poverty has increased over the past four years—from 11 percent in 2019 to almost 26 percent in 2024 in Sri Lanka. It further states that approximately 60 percent of Sri Lankan households have decreased incomes, with many facing increased food insecurity, malnutrition and stunted growth.

The decision of Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith and the Catholic Church to take their unaddressed grievance to the UNHRC in Geneva is a sign of the pain and suffering due to injustice that continues to burn within the hearts and minds of people, especially those who fell victim and those who are involved with them. Whether or not Ukraine and Gaza figure in the forthcoming resolutions of the UNHRC, it can be expected that Sri Lanka which has been on the agenda will continue to remain on the agenda. Sustaining the present peace in Sri Lanka requires that change that goes beyond a change of faces in government. It requires a new governmental commitment that the two main opposition political parties are promising and the government needs to match.

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka Resorts of Cinnamon Hotels & Resorts mark Earth Day with impactful eco-initiatives

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog Axiata recognised as the Most Significant FDI Contributor by BOI

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoUNESCAP Technical Cooperation Highlights Report flags significant strides in its partnership with Sri Lanka

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoComBank crowned ‘Best Bank in Sri Lanka’ by Global Finance for 22nd year

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoCinnamon Lakeside Colombo welcomes Nazoomi Azhar as its new General Manager

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGerman research ship allowed Sri Lanka port call after Chinese-protest led clarification

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSri Lankan Oil and Gas exploration grinds to a standstill amid protracted legal battle

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoShocks from Bills