Opinion

Remembering “Walloops”: Father of Cardiology in SL

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

The pioneering Cardiologist Dr Narendradas Jayaratnam Wallooppillai, affectionately referred to as “Walloops” by his friends, who succumbed to heart failure on 6th January 2011, surely deserves the title ‘The Father of Cardiology in Sri Lanka’ because it was during his tenure that Cardiology came to its own as a speciality. However, he was not the first to head the Cardiology Unit of the General hospital, Colombo. That distinction goes to Dr Ivor Obeysekara who, in spite of fighting against all odds to establish a dedicated Cardiology Unit, took early retirement and left for Australia. Dr Obeysrekara’s tenure was short, not having sufficient time to develop the speciality, the Cardiology Unit functioning as a Cardiology ward during his time.

Dr Wallooppillai was born on 6th June 1925, to the wealthy and influential Velupillai family which settled in Balangoda thanks to the hospitality of the Ratwatte family; the ancestors of Mrs Sirimavo Ratwatte Dias Bandaranaike. It is said that when he was admitted to St. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia, the warden, Canon De Saram, changed the spelling of his name from Velupillai to Wallooppillai as he thought it was more user friendly. He graduated from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Ceylon in 1951 and proceeded soon after to UK. He obtained MRCP (London) and MRCP Cardiology (Edinburgh), undergoing training in Cardiology in Manchester.

On his return he was appointed Consultant Physician, General Hospital, Jaffna. Subsequently he was appointed the first Physician-in-charge of the Cardiac Investigation Unit (CIU) in General Hospital, Colombo which was set up around the same time as the Cardiology Unit. Dr Mahinda Weerasena was appointed the Consultant Cardiac Radiologist to this Unit and Dr Thistle Jayawardena, Consultant Anaesthetist, who was instrumental in setting up the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (the first intensive care unit in the country), joined later.

I was fortunate to know Dr Wallooppillai from June 1968, when I became his Registrar, and owe my entire training in Cardiology to him. I pride myself in being the first Cardiologist to be trained entirely in Sri Lanka and it is a credit to his tutelage that even after leaving Sri Lanka, I was able not only to practice Cardiology in UK but also set up an acclaimed Cardiology service in Grantham Hospital. For this, I am eternally indebted to him.

How I got to working with Walloops is an interesting story. Whilst working as the Registrar in the Professorial Medical Unit of the Peradeniya Medical Faculty under Professor Ajwad Macan Markar and Senior Lecturer Dr T. Varagunam, I obtained M D (Ceylon) degree in December 1967. Though I had a further 18 months of my secondment to the Professorial Unit left, the Department of Health withdrew me and appointed me Resident Physician, General Hospital Kandy. To my surprise, I got a call from the Department inquiring whether I would be interested in the post of Registrar CIU in General Hospital, Colombo. Having ascertained that this unexpected offer was simply because there were no applicants in spite of the post being advertised twice, I decided to meet Dr ‘Kalu’ Jayasinghe, the Assistant Director of Hospitals to have a chat. Whilst admitting that Wallops is a tough task-master, he advised me to take it as it would be my opening to the speciality of Cardiology which was in its infancy at the time. I owe a debt of gratitude to Dr Jayasinghe for that sound advice which changed my life forever.

My initial reservations soon vanished as I found Dr Wallooppillai to be a great teacher, very inspirational one at that, as well as an efficient organiser. He shaped the career of many, including myself, who practice/d Cardiology not only in Sri Lanka but around the world. I enjoyed the work so much that it was with a very heavy heart I left the CIU in September 1969 to go to UK on a Departmental Scholarship for Post-graduate qualifications.

On my return with MRCP (UK) in early 1972, I was appointed Consultant Physician, General Hospital, Badulla. Shortly after that Dr Wallooppillai was appointed Cardiologist and he suggested that I state my claim to succeed him as the Physician-in-charge of CIU. Before I could do so, the Director of Health Services appointed another without even an advertisement, contrary to existing regulations! A long battle ensued and, finally, the Department offered to appoint two physicians to CIU but Dr Wallooppillai advised against taking up that appointment. Instead, he created a post of Registrar in Cardiology which I accepted in June 1973, in spite of having to step down from the position of a Consultant in a provincial hospital. I do not regret that decision as I was able to assist Walloops in developing Cardiology as a speciality. In 1975 Coronary Care Unit, the first medical intensive care unit in the country, opened and progress was relentless since. He gave me a free hand, as well as all the support, to develop the permanent pacing programme. The seeds that were sown blossomed out, Cardiology being one of the most advanced specialities in the country today.

My batch-mate as well as Jeewaka hostel-mate, Dr D. P.Atukorale was due to return after training in Cardiology in Manchester in late September 1973 and Walloops got information that he would be sent to Ratnapura where there were no facilities at all. He tasked me to meet Atu at the airport and take him home with the advice not to report to work till he sorted something out which he did. Atu joined us as another Registrar. During George Rajapaksa’s time as the Minister of Health, we were re-designated Assistant Cardiologists at the suggestion of Walloops.

On his retirement on 6th June 1985, I succeeded Dr Wallooppillai after a much-publicised ‘Cardiology Stake’. For about a month, newspapers were full of articles as a trade union claimed that two others were more suited to the job but I ‘won the battle’ because I had the highest number of points according to the system of selection in place. Ultimately, it was left for President Jayewardene to check the tally in front of the Minister to make the decision, it was rumoured! Undeterred, the trade union continued with strikes and other trade union actions which led to an effective division of the unit in March 1987. I was appointed the Senior Cardiologist-in-charge of the Institute of Cardiology, the other two being appointed Cardiologists. I was given the option of early retirement which I took in April 1988 which opened a new era for me.

During all these turbulent times, Dr Wallooppillai was my ‘rock’. I could depend on him for advice and support in all matters. He taught me not only Cardiology but also how to fight for principles. He was like a second father to me. His wife, Yoges, who pre-deceased him, showered kindness. They had no children but brought up Yoges’ sister’s daughter, Mala, till she passed ‘O’ levels at Ladies College and returned to her family living in London.

What was most impressive to me about Walloops was his absolute honesty and integrity. He reinforced the values imparted to me by my parents. He was held in high esteem and held many high positions. He was the President of the Ceylon College of Physicians, President of the Sri Lanka Heart Association for many years and the President of the Orchid Circle. His hobby was growing orchids and his garden was filled with wonderful, rare blooms. However, most remarkable was his time as the President of the Sri Lanka Medical Association in 1980, when I was the Honorary Secretary. I have served many Presidents as Assistant Secretary and Secretary of SLMA but no one equals Walloops. The monthly council meetings were a pleasure to attend. There was no straying from the points under discussion and the meetings were crisp, concise and always finished on time.

Though shy by nature avoiding large gatherings and a man of a few words, paradoxically, he was a trade union leader too! He was the President of the Association of Medical Specialists for many years and demonstrated to other trade unionists that justice for members could be extracted without confrontation and trade union action like strikes, by using the art of diplomacy which he excelled in.

After leaving Sri Lanka, on every trip back home I never missed seeing him. It was sad to see him gradually developing heart failure following a silent heart attack. When I saw him in February 2010, I did not expect to see him again but to my surprise I saw him again in October the same year, seeing private patients in Healthcare Laboratories.

The day before his death, Mala rang me to get my address as ‘Appa’ wanted to send me a note. When I received it, after his death, I realised it was his Goodbye message.

If there an afterlife, Walloops is one colossus I would love to meet again. Until then Sir, pleasant memories of a great life of service to rich and poor alike!

Opinion

The science of love

A remarkable increase in marriage proposals in newspapers and the thriving matchmaking outfits in major cities indicate the difficulty in finding the perfect partners. Academics have done much research in interpersonal attraction or love. There was an era when young people were heavily influenced by romantic fiction. They learned how opposites attract and absence makes the heart grow fonder. There was, of course, an old adage: Out of sight out of mind.

Some people find it difficult to fall in love or they simply do not believe in love. They usually go for arranged marriages. Some of them think that love begins after marriage. There is an on-going debate whether love marriages are better than arranged marriages or vice versa. However, modern psychologists have shed some light on the science of love. By understanding it you might be able to find the ideal life partner.

To start with, do not believe that opposites attract. It is purely a myth. If you wish to fall in love, look for someone like you. You may not find them 100 per cent similar to you, but chances are that you will meet someone who is somewhat similar to you. We usually prefer partners who have similar backgrounds, interests, values and beliefs because they validate our own.

Common trait

It is a common trait that we gravitate towards those who are like us physically. The resemblance of spouses has been studied by scientists more than 100 years ago. According to them, physical resemblance is a key factor in falling in love. For instance, if you are a tall person, you are unlikely to fall in love with a short person. Similarly, overweight young people are attracted to similar types. As in everything in life, there may be exceptions. You may have seen some tall men in love with short women.

If you are interested in someone, declare your love in words or gestures. Some people have strong feelings about others but they never make them known. If you fancy someone, make it known. If you remain silent you will miss a great opportunity forever. In fact if someone loves you, you will feel good about yourself. Such feelings will strengthen love. If someone flatters you, be nice to them. It may be the beginning of a great love affair.

Some people like Romeo and Juliet fall in love at first sight. It has been scientifically confirmed that the longer a pair of prospective partners lock eyes upon their first meeting they are very likely to remain lovers. They say eyes have it. If you cannot stay without seeing your partner, you are in love! Whenever you meet your lover, look at their eyes with dilated pupils. Enlarged pupils signal intense arousal.

Body language

If you wish to fall in love, learn something about body language. There are many books written on the subject. The knowledge of body language will help you to understand non-verbal communication easily. It is quite obvious that lovers do not express their love in so many words. Women usually will not say ‘I love you’ except in films. They express their love tacitly with a shy smile or preening their hair in the presence of their lovers.

Allan Pease, author of The Definitive Guide to Body Language says, “What really turn men on are female submission gestures which include exposing vulnerable areas such as the wrists or neck.” Leg twine was something Princess Diana was good at. It involves crossing the legs hooking the upper leg’s foot behind the lower leg’s ankle. She was an expert in the art of love. Men have their own ways. In order to look more dominant than their partners they engage in crotch display with their thumbs hooked in pockets. Michael Jackson always did it.

If you are looking for a partner, be a good-looking guy. Dress well and behave sensibly. If your dress is unclean or crumpled, nobody will take any notice of you. According to sociologists, men usually prefer women with long hair and proper hip measurements. Similarly, women prefer taller and older men because they look nice and can be trusted to raise a family.

Proximity rule

You do not have to travel long distances to find your ideal partner. He or she may be living in your neighbourhood or working at the same office. The proximity rule ensures repeated exposure. Lovers should meet regularly in order to enrich their love. On most occasions we marry a girl or boy living next door. Never compare your partner with your favourite film star. Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder. Therefore be content with your partner’s physical appearance. Each individual is unique. Never look for another Cleopatra or Romeo. Sometimes you may find that your neighbour’s wife is more beautiful than yours. On such occasions turn to the Bible which says, “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife.”

There are many plain Janes and penniless men in society. How are they going to find their partners? If they are warm people, sociable, wise and popular, they too can find partners easily. Partners in a marriage need not be highly educated, but they must be intelligent enough to face life’s problems. Osho compared love to a river always flowing. The very movement is the life of the river. Once it stops it becomes stagnant. Then it is no longer a river. The very word river shows a process, the very sound of it gives you the feeling of movement.

Although we view love as a science today, it has been treated as an art in the past. In fact Erich Fromm wrote The Art of Loving. Science or art, love is a terrific feeling.

karunaratners@gmail.com

By R.S. Karunaratne

Opinion

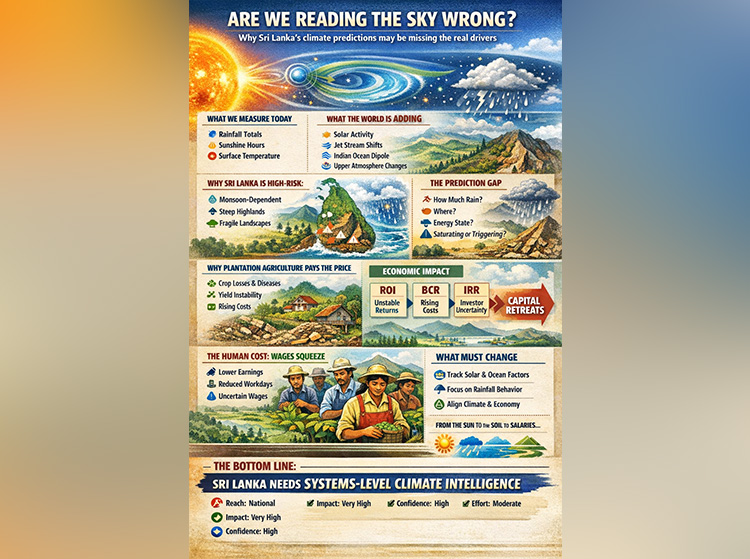

Are we reading the sky wrong?

Rethinking climate prediction, disasters, and plantation economics in Sri Lanka

For decades, Sri Lanka has interpreted climate through a narrow lens. Rainfall totals, sunshine hours, and surface temperatures dominate forecasts, policy briefings, and disaster warnings. These indicators once served an agrarian island reasonably well. But in an era of intensifying extremes—flash floods, sudden landslides, prolonged dry spells within “normal” monsoons—the question can no longer be avoided: are we measuring the climate correctly, or merely measuring what is easiest to observe?

Across the world, climate science has quietly moved beyond a purely local view of weather. Researchers increasingly recognise that Earth’s climate system is not sealed off from the rest of the universe. Solar activity, upper-atmospheric dynamics, ocean–atmosphere coupling, and geomagnetic disturbances all influence how energy moves through the climate system. These forces do not create rain or drought by themselves, but they shape how weather behaves—its timing, intensity, and spatial concentration.

Sri Lanka’s forecasting framework, however, remains largely grounded in twentieth-century assumptions. It asks how much rain will fall, where it will fall, and over how many days. What it rarely asks is whether the rainfall will arrive as steady saturation or violent cloudbursts; whether soils are already at failure thresholds; or whether larger atmospheric energy patterns are priming the region for extremes. As a result, disasters are repeatedly described as “unexpected,” even when the conditions that produced them were slowly assembling.

This blind spot matters because Sri Lanka is unusually sensitive to climate volatility. The island sits at a crossroads of monsoon systems, bordered by the Indian Ocean and shaped by steep central highlands resting on deeply weathered soils. Its landscapes—especially in plantation regions—have been altered over centuries, reducing natural buffers against hydrological shock. In such a setting, small shifts in atmospheric behaviour can trigger outsized consequences. A few hours of intense rain can undo what months of average rainfall statistics suggest is “normal.”

Nowhere are these consequences more visible than in commercial perennial plantation agriculture. Tea, rubber, coconut, and spice crops are not annual ventures; they are long-term biological investments. A tea bush destroyed by a landslide cannot be replaced in a season. A rubber stand weakened by prolonged waterlogging or drought stress may take years to recover, if it recovers at all. Climate shocks therefore ripple through plantation economics long after floodwaters recede or drought declarations end.

From an investment perspective, this volatility directly undermines key financial metrics. Return on Investment (ROI) becomes unstable as yields fluctuate and recovery costs rise. Benefit–Cost Ratios (BCR) deteriorate when expenditures on drainage, replanting, disease control, and labour increase faster than output. Most critically, Internal Rates of Return (IRR) decline as cash flows become irregular and back-loaded, discouraging long-term capital and raising the cost of financing. Plantation agriculture begins to look less like a stable productive sector and more like a high-risk gamble.

The economic consequences do not stop at balance sheets. Plantation systems are labour-intensive by nature, and when financial margins tighten, wage pressure is the first stress point. Living wage commitments become framed as “unaffordable,” workdays are lost during climate disruptions, and productivity-linked wage models collapse under erratic output. In effect, climate misprediction translates into wage instability, quietly eroding livelihoods without ever appearing in meteorological reports.

This is not an argument for abandoning traditional climate indicators. Rainfall and sunshine still matter. But they are no longer sufficient on their own. Climate today is a system, not a statistic. It is shaped by interactions between the Sun, the atmosphere, the oceans, the land, and the ways humans have modified all three. Ignoring these interactions does not make them disappear; it simply shifts their costs onto farmers, workers, investors, and the public purse.

Sri Lanka’s repeated cycle of surprise disasters, post-event compensation, and stalled reform suggests a deeper problem than bad luck. It points to an outdated model of climate intelligence. Until forecasting frameworks expand beyond local rainfall totals to incorporate broader atmospheric and oceanic drivers—and until those insights are translated into agricultural and economic planning—plantation regions will remain exposed, and wage debates will remain disconnected from their true root causes.

The future of Sri Lanka’s plantations, and the dignity of the workforce that sustains them, depends on a simple shift in perspective: from measuring weather, to understanding systems. Climate is no longer just what falls from the sky. It is what moves through the universe, settles into soils, shapes returns on investment, and ultimately determines whether growth is shared or fragile.

The Way Forward

Sustaining plantation agriculture under today’s climate volatility demands an urgent policy reset. The government must mandate real-world investment appraisals—NPV, IRR, and BCR—through crop research institutes, replacing outdated historical assumptions with current climate, cost, and risk realities. Satellite-based, farm-specific real-time weather stations should be rapidly deployed across plantation regions and integrated with a central server at the Department of Meteorology, enabling precision forecasting, early warnings, and estate-level decision support. Globally proven-to-fail monocropping systems must be phased out through a time-bound transition, replacing them with diversified, mixed-root systems that combine deep-rooted and shallow-rooted species, improving soil structure, water buffering, slope stability, and resilience against prolonged droughts and extreme rainfall.

In parallel, a national plantation insurance framework, linked to green and climate-finance institutions and regulated by the Insurance Regulatory Commission, is essential to protect small and medium perennial growers from systemic climate risk. A Virtual Plantation Bank must be operationalized without delay to finance climate-resilient plantation designs, agroforestry transitions, and productivity gains aligned with national yield targets. The state should set minimum yield and profit benchmarks per hectare, formally recognize 10–50 acre growers as Proprietary Planters, and enable scale through long-term (up to 99-year) leases where state lands are sub-leased to proven operators. Finally, achieving a 4% GDP contribution from plantations requires making modern HRM practices mandatory across the sector, replacing outdated labour systems with people-centric, productivity-linked models that attract, retain, and fairly reward a skilled workforce—because sustainable competitive advantage begins with the right people.

by Dammike Kobbekaduwe

(www.vivonta.lk & www.planters.lk ✍️

Opinion

Disasters do not destroy nations; the refusal to change does

Sri Lanka has endured both kinds of catastrophe that a nation can face, those caused by nature and those created by human hands. A thirty-year civil war tore apart the social fabric, deepening mistrust between communities and leaving lasting psychological wounds, particularly among those who lived through displacement, loss, and fear. The 2004 tsunami, by contrast, arrived without warning, erasing entire coastal communities within minutes and reminding us of our vulnerability to forces beyond human control.

These two disasters posed the same question in different forms: did we learn, and did we change? After the war ended, did we invest seriously in repairing relationships between Sinhalese and Tamil communities, or did we equate peace with silence and infrastructure alone? Were collective efforts made to heal trauma and restore dignity, or were psychological wounds left to be carried privately, generation after generation? After the tsunami, did we fundamentally rethink how and where we build, how we plan settlements, and how we prepare for future risks, or did we rebuild quickly, gratefully, and then forget?

Years later, as Sri Lanka confronts economic collapse and climate-driven disasters, the uncomfortable truth emerges. we survived these catastrophes, but we did not allow them to transform us. Survival became the goal; change was postponed.

History offers rare moments when societies stand at a crossroads, able either to restore what was lost or to reimagine what could be built on stronger foundations. One such moment occurred in Lisbon in 1755. On 1 November 1755, Lisbon-one of the most prosperous cities in the world, was almost completely erased. A massive earthquake, estimated between magnitude 8.5 and 9.0, was followed by a tsunami and raging fires. Churches collapsed during Mass, tens of thousands died, and the royal court was left stunned. Clergy quickly declared the catastrophe a punishment from God, urging repentance rather than reconstruction.

One man refused to accept paralysis as destiny. Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, later known as the Marquês de Pombal, responded with cold clarity. His famous instruction, “Bury the dead and feed the living,” was not heartless; it was revolutionary. While others searched for divine meaning, Pombal focused on human responsibility. Relief efforts were organised immediately, disease was prevented, and plans for rebuilding began almost at once.

Pombal did not seek to restore medieval Lisbon. He saw its narrow streets and crumbling buildings as symbols of an outdated order. Under his leadership, Lisbon was rebuilt with wide avenues, rational urban planning, and some of the world’s earliest earthquake-resistant architecture. Moreover, his vision extended far beyond stone and mortar. He reformed trade, reduced dependence on colonial wealth, encouraged local industries, modernised education, and challenged the long-standing dominance of aristocracy and the Church. Lisbon became a living expression of Enlightenment values, reason, science, and progress.

Back in Sri Lanka, this failure is no longer a matter of opinion. it is documented evidence. An initial assessment by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) following Cyclone Ditwah revealed that more than half of those affected by flooding were already living in households facing multiple vulnerabilities before the cyclone struck, including unstable incomes, high debt, and limited capacity to cope with disasters (UNDP, 2025). The disaster did not create poverty; it magnified it. Physical damage was only the visible layer. Beneath it lay deep social and economic fragility, ensuring that for many communities, recovery would be slow, uneven, and uncertain.

The world today offers Sri Lanka another lesson Lisbon understood centuries ago: risk is systemic, and resilience cannot be improvised, it must be planned. Modern climate science shows that weather systems are deeply interconnected; rising ocean temperatures, changing wind patterns, and global emissions influence extreme weather far beyond their points of origin. Floods, landslides, and cyclones affecting Sri Lanka are no longer isolated events, but part of a broader climatic shift. Rebuilding without adapting construction methods, land-use planning, and infrastructure to these realities is not resilience, it is denial. In this context, resilience also depends on Sri Lanka’s willingness to learn from other countries, adopt proven technologies, and collaborate across borders, recognising that effective solutions to global risks cannot be developed in isolation.

A deeper problem is how we respond to disasters: we often explain destruction without seriously asking why it happened or how it could have been prevented. Time and again, devastation is framed through religion, fate, karma, or divine will. While faith can bring comfort in moments of loss, it cannot replace responsibility, foresight, or reform. After major disasters, public attention often focuses on stories of isolated religious statues or buildings that remain undamaged, interpreted as signs of protection or blessing, while far less attention is paid to understanding environmental exposure, construction quality, and settlement planning, the factors that determine survival. Similarly, when a single house survives a landslide, it is often described as a miracle rather than an opportunity to study soil conditions, building practices, and land-use decisions. While such interpretations may provide emotional reassurance, they risk obscuring the scientific understanding needed to reduce future loss.

The lesson from Lisbon is clear: rebuilding a nation requires the courage to question tradition, the discipline to act rationally, and leadership willing to choose long-term progress over short-term comfort. Until Sri Lanka learns to rebuild not only roads and buildings, but relationships, institutions, and ways of thinking, we will remain a country trapped in recovery, never truly reborn.

by Darshika Thejani Bulathwatta

Psychologist and Researcher

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoGeneral education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSuspension of Indian drug part of cover-up by NMRA: Academy of Health Professionals

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoChief selector’s remarks disappointing says Mickey Arthur

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoUS Ambassador to Sri Lanka among 29 career diplomats recalled

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoA very sad day for the rule of law