Features

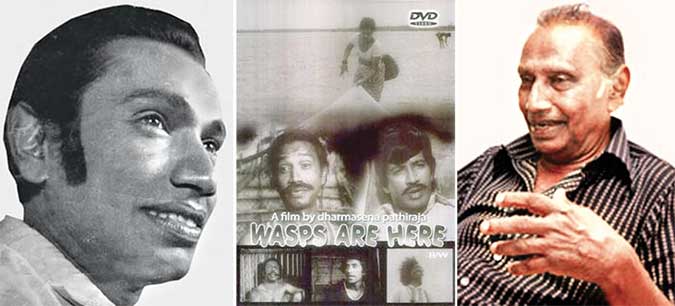

Reflecting on Cyril wickramage

By Uditha Devapriya

\Although the Colombo Film Society would become Asia’s oldest such group, Colombo lay a world or two away from the rest of Sri Lanka. The urban middle-classes encountered the best of regional and Western cinema before their counterparts in Bombay and Calcutta did, but they remained cut off from a vast multitude who never as much as came across English films. The rural middle-classes, on the other hand, had a somewhat different conception of the cinema. The idea of a film theatre was alien to them: they were familiar with travelling cinemas and drama troupes instead. It was later, when they migrated to Colombo, that they came across the world beyond the Madras studio and the Nurti drama.

Cyril Wickramage hailed from this milieu. Born in Kohilagedara in Kurunegala on January 26, 1932, Wickramage grew up on a diet of Sokari, Nadagam, and Nurti. Kohilagedara lay less than 75 kilometres from Negombo, and drama troupes from there would visit his village, enthralling him and his friends. The villagers grew to love these shows so much that they became the centrepiece of Avurudu festivities: “When April came, we would look forward to yet another Nurti drama.” Although neither he nor his friends wanted to act, they turned these encounters into an integral part of their common experience. Elsewhere in Lellopitiya in Ratnapura, Joe Abeywickrema was indulging in such encounters too.

Like Abeywickrema, Wickramage did not get to see many films in his early years. The closest movie theatre, the Imperial, was in Kurunegala town, and that lay 12 kilometres away from Kohilagedara. Yet he would not infrequently get together with his friends, and sometimes family, and just go there. “Back then we didn’t see many English films. Most of them were in Sinhala or Tamil.” Wickramage was about 15 when the Minerva Players released Kadawunu Poronduwa. He did not readily admit it to me, but perhaps the symbiotic link between the early Sinhala films and Nurti and Nadagam drama appealed to him. In any case, it wasn’t just Sinhala films that he liked: he remembered doting on Jayalalitha also.

Wickramage’s first love was the army. Having flirted with the idea of joining the military, however, he let it go in favour of a career in teaching. Having left school, he enrolled at the Peradeniya Training College for a two-year course. Thereafter he was employed as a teacher at a total of seven schools: they included the Ratmalana Deaf and Blind School and Wesley College in Colombo. These stints not only helped him get deep into a career he had grown to love, they also enabled him to pursue his love for music, drama, and dancing. More than any other institution, it was Wesley that got him thinking about the performing arts. Run by the very able and competent Shelton Wirasinha, Wesley College was seeing its peak years, a veritable flourishing of the arts. Wickramage could not escape this.

Participating in a school play, Wickramage made the acquaintance of Ananda Samarakoon. Samarakoon, whose talents were just as attuned to music as they were to the performing arts, encouraged the young teacher to try his hand at the theatre. While the muse beckoned him on, however, it was the cinema that would officially initiate him to the world of the performing arts. In 1965 Wickramage got his first role, opposite Vijitha Mallika in Kingsley Rajapakse’s Handapane. Though a minor role, it got him much praise from those who knew him. The connections he had set up during these years turned to his advantage when, a few months later, he was contacted by Siri Gunasinghe. Gunasinghe would doubtless have seen the man’s talent for playing introspective characters and he cast him in the role of the tragic protagonist in his first and only film, Sath Samudura, in 1966.

Gunasinghe’s film was a watershed in many ways. As the title implies, Sath Samudura was set in a fishing community. It was not the first Sinhala film to be set in such a milieu: just the previous year Gamini Fonseka and Joe Abeywickrema had enthralled audiences with their performances in Getawarayo, which wound up as the Best Film at that year’s Sarasavi Awards. Yet Sath Samudura was the first Sinhala film to explore realistically, with no artifice or contrivance, the torments and agonies of the country’s fishing community. While far from being a docudrama, the story rang true in ways that other films based in such settings did not. Wickramage’s performance, as with the other performances – Denawaka Hamine’s and Swarna Mallawarachchi’s – helped make the film more authentic.

These were, by all accounts, exhilarating years for the local cinema. The revolution that Lester Peries unleashed through Rekava (1956) was still being felt everywhere, and by everyone. Following him in his wake were an entirely different generation of cineastes, who owed their careers to him but sought to go beyond his vision. Siri Gunasinghe’s film was a landmark in the Sinhala cinema, yet it did not fundamentally question or challenge Lester’s conception of the medium: it too belonged to the humanist-realist mode. During this time, Wickramage associated with three people who would figure in the next stage in the Sri Lankan cinema: Dr Linus Dissanayake, producer of Sath Samudura, Vasantha Obeyesekere, Gunasinghe’s Assistant Director, and Dharmasena Pathiraja.

Dissanayake helped finance and produce Obeyesekere’s debut film, Wes Gaththo, in 1970. Cast as the protagonist, Wickramage revelled in a role he was to typify in the years to come: the uprooted, wayward urban dweller. Five years later he gave one of his best performances in Obeyesekere’s next film, Walmath Wuwo. Cast opposite the likes of Tony Ranasinghe, the film explores the plight of unemployed university graduates, who seek fairer climes and greener pastures and migrate to the city with much expectation, but instead find a life of perpetual drudgery. It depicts rather accurately the hopes, dreams, wishes, the torments and the agonies, of an assertive but frustrated Sinhala rural petty bourgeoisie. Hailing from such a milieu himself, Wickramage gave a remarkably true to life performance: in one scene he performs a Nadagam song, no doubt going back to his childhood years.

Between Wes Gaththo and Walmath Wuwo Wickramage took part in a great many films and made friends with a great many directors, actors, and other crew members. Among those he befriended very closely were Dharmasena Pathiraja and Daya Tennakoon. Through his films, Pathiraja had brought together a group of actors that, while not formally constituting a repertoire, nevertheless became a regular feature of his films. These included Tennakoon as well as Amarasiri Kalansuriya and Vijaya Kumaratunga. Wickramage made friends with them all, and in doing so went on to epitomise the spirit of a new age: as far away from the 1960s as the 1960s had been from the 1950s. The films made during this time were full of rebellion, and the directors who made their mark at this juncture wanted to break free from the limits of the past. No director symbolised this more fittingly than Pathiraja.

Wickramage’s best performance in a Pathiraja film would have to be in Bambaru Avith (1977). The film is an allegory about the intrusion of capitalism into the lives and ways of a fishing community. Wickramage is affianced to Helen, a beautiful fisherman’s daughter played by Malini Fonseka. The protagonist of the story, Victor (Vijaya Kumaratunga) soon becomes infatuated with her. The film does not explain why exactly Wickramage’s character hates Victor so passionately, but the conflict between Victor and the fishing community exacerbates because of Helen’s relationship with these two men.

When television came to Sri Lanka in the late 1970s Wickramage found a very different niche. While on film he had been content in playing a certain role, on television he played diverse characters from different milieux. Sometimes these characters are sympathetic, often they are not. In Ella Langa Walawwa, for instance, it is Wickramage who holds the narrative together as the servant, and in Kadulla he epitomises – through his death – the conflict between the old order and the new in 19th century colonial society. Both these productions were directed by Pathiraja; they would be followed by other serials, the most memorable of which, from this decade at least, would have to be Ananda Abeynayake’s Kande Gedara. Here, in contrast to his earlier roles, he plays a conman who dreams of going up and exhibits one mannerism after another to pass off as respectable.

Over the next few years and decades, Wickramage would mellow gracefully. Though he does not act as much as he used to, his recent performances depict a more empathetic, world-weary, sagacious side to him. His career resembles that of other supporting actors, like Daya Tennakoon, who never became leading men, but who became indispensable parts of the films they starred in. Today, at 91, Wickramage has become an elder statesman in the world of the Sinhala film. Whether or not his due honours have been paid is debatable. That he is deserving of these honours, of course, there is no doubt.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@-gmail.com

Features

More state support needed for marginalised communities

Message from Malaiyaha Tamil community to govt:

Insights from SSA Cyclone Ditwah Survey

When climate disasters strike, they don’t affect everyone equally. Marginalised communities typically face worse outcomes, and Cyclone Ditwah is no exception. Especially in a context where normalcy is far from “normal”, the idea of returning to normalcy or restoring a life of normalcy makes very little sense.

The island-wide survey (https://ssalanka.org/reports/) conducted by the Social Scientists’ Association (SSA), between early to mid-January on Cyclone Ditwah shows stark regional disparities in how satisfied or dissatisfied people were with the government’s response. While national satisfaction levels were relatively high in most provinces, the Central Province tells a different story.

Only 35.2% of Central Province residents reported that they were satisfied with early warning and evacuation measures, compared to 52.2% nationally. The gap continues across every measure: just 52.9% were satisfied with immediate rescue and emergency response, compared with the national figure of 74.6%. Satisfaction with relief distribution in the Central Province is 51.9% while the national figure stands at 73.1%. The figures for restoration of water, electricity, and roads are at a low 45.9% in the central province compared to the 70.9% in national figures. Similarly, the satisfaction level for recovery and rebuilding support is 48.7% in the Central Province, while the national figure is 67.0%.

A deeper analysis of the SSA data on public perceptions reveals something important: these lower satisfaction rates came primarily from the Malaiyaha Tamil population. Their experience differed not just from other provinces, but also from other ethnic groups living in the Central Province itself.

The Malaiyaha Tamil community’s vulnerability didn’t start with the cyclone. Their vulnerability is a historically and structurally pre-determined process of exclusion and marginalisation. Brought to Sri Lanka during British rule to work for the empire’s plantation economies, they have faced long-term economic exploitation and have repeatedly been denied access to state support and social welfare systems. Most estate residents still live in ‘line rooms’ and have no rights to the land they cultivate and live on. The community continues to be governed by an outdated estate management system that acts as a barrier to accessing public and municipal services such as road repair, water, electricity and other basic infrastructures available to other citizens.

As far as access to improved water sources is concerned, the Sri Lanka Demographic Health Survey (2016) shows that 57% of estate sector households don’t have access to improved water sources, while more than 90% of households in urban and rural areas do. With regard to the level of poverty, as the Department of Census and Statistics (2019) data reveals, the estate sector where most Malaiyaha Tamils live had a poverty headcount index of 33.8%; more than double the national rate of 14.3%. These statistics highlight key indicators of the systemic discrimination faced by the Malaiyaha Tamil community.

Some crucial observations from the SSA data collectors who enumerated responses from estate residents in the survey reveal the specific challenges faced by the Malaiyaha Tamils, particularly in their efforts to seek state support for compensation and reconstruction.

First, the Central Province experienced not just flooding but also the highest number of landslides in the island. As a result, some residents in the region lost entire homes, access roadways, and other basic infrastructures. The loss of lives, livelihoods and land was at a higher intensity compared to the provinces not located in the hills. Most importantly, the Malaiyaha Tamil community’s pre-existing grievances made them even more vulnerable and the government’s job of reparation and restitution more complex.

Early warnings hadn’t reached many areas. Some data collectors said they themselves never heard any warnings in estate areas, while others mentioned that early warnings were issued but didn’t reach some segments of the community. According to the resident data collectors, the police announcements reached only as far as the sections where they were able to drive their vehicles to, and there were many estate roads that were not motorable. When warnings did filter through to remote locations, they often came by word of mouth and information was distorted along the way. Once the disaster hit, things got worse: roads were blocked, electricity went out, mobile networks failed and people were cut off completely.

Emergency response was slow. Blocked roads meant people could not get to hospitals when they needed urgent care, including pregnant mothers. The difficult terrain and poor road conditions meant rescue teams took much longer to reach affected areas than in other regions.

Relief supplies didn’t reach everyone. The Grama Niladhari divisions in these areas are huge and hard to navigate, making it difficult for Grama Niladharis to reach all places as urgently as needed. Relief workers distributed supplies where vehicles could go, which meant accessible areas got help while remote communities were left out.

Some people didn’t even try to go to safety centres or evacuation shelters set up in local schools because the facilities there were already so poor. The perceptions of people who did go to safety centres, as shown in the provincial data, reveal that satisfaction was low compared to other affected regions of the country. Less than half were satisfied with space and facilities (42.1%) or security and protection (45.0%). Satisfaction was even lower for assistance with lost or damaged documentation (17.9%) and information and support for compensation applications (28.2%). Only 22.5% were satisfied with medical care and health services below most other affected regions.

Restoring services proved nearly impossible in some areas. Road access was the biggest problem. The condition of the roads was already poor even before the cyclone, and some still haven’t been cleared. Recovery is especially difficult because there’s no decent baseline infrastructure to restore, hence you can’t bring roads and other public facilities back to a “good” condition when they were never good, even before the disaster.

Water systems faced their own complications. Many households get water from natural sources or small community projects, and not the centralised state system. These sources are often in the middle of the disaster zone and therefore got contaminated during the floods and landslides.

Long-term recovery remains stalled. Without basic infrastructure, areas that are still hard to reach keep struggling to get the support they need for rebuilding.

Taken together, what do these testaments mean? Disaster response can’t be the same for everyone. The Malaiyaha Tamil community has been double marginalised because they were already living with structural inequalities such as poor infrastructure, geographic isolation, and inadequate services which have been exacerbated by Cyclone Ditwah. An effective and fair disaster response needs to account for these underlying vulnerabilities. It requires interventions tailored to the historical, economic, and infrastructural realities that marginalized communities face every day. On top of that, it highlights the importance of dealing with climate disasters, given the fact that vulnerable communities could face more devastating impacts compared to others.

(Shashik Silva is a researcher with the Social Scientists’ Association of Sri Lanka)

by Shashik Silva ✍️

Features

Crucial test for religious and ethnic harmony in Bangladesh

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

The apprehensions are mainly on the part of religious and ethnic minorities. The parliamentary poll of February 12th is expected to bring into existence a government headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Islamist oriented Jamaat-e-Islami party and this is where the rub is. If these parties win, will it be a case of Bangladesh sliding in the direction of a theocracy or a state where majoritarian chauvinism thrives?

Chief of the Jamaat, Shafiqur Rahman, who was interviewed by sections of the international media recently said that there is no need for minority groups in Bangladesh to have the above fears. He assured, essentially, that the state that will come into being will be equable and inclusive. May it be so, is likely to be the wish of those who cherish a tension-free Bangladesh.

The party that could have posed a challenge to the above parties, the Awami League Party of former Prime Minister Hasina Wased, is out of the running on account of a suspension that was imposed on it by the authorities and the mentioned majoritarian-oriented parties are expected to have it easy at the polls.

A positive that has emerged against the backdrop of the poll is that most ordinary people in Bangladesh, be they Muslim or Hindu, are for communal and religious harmony and it is hoped that this sentiment will strongly prevail, going ahead. Interestingly, most of them were of the view, when interviewed, that it was the politicians who sowed the seeds of discord in the country and this viewpoint is widely shared by publics all over the region in respect of the politicians of their countries.

Some sections of the Jamaat party were of the view that matters with regard to the orientation of governance are best left to the incoming parliament to decide on but such opinions will be cold comfort for minority groups. If the parliamentary majority comes to consist of hard line Islamists, for instance, there is nothing to prevent the country from going in for theocratic governance. Consequently, minority group fears over their safety and protection cannot be prevented from spreading.

Therefore, we come back to the question of just and fair governance and whether Bangladesh’s future rulers could ensure these essential conditions of democratic rule. The latter, it is hoped, will be sufficiently perceptive to ascertain that a Bangladesh rife with religious and ethnic tensions, and therefore unstable, would not be in the interests of Bangladesh and those of the region’s countries.

Unfortunately, politicians region-wide fall for the lure of ethnic, religious and linguistic chauvinism. This happens even in the case of politicians who claim to be democratic in orientation. This fate even befell Bangladesh’s Awami League Party, which claims to be democratic and socialist in general outlook.

We have it on the authority of Taslima Nasrin in her ground-breaking novel, ‘Lajja’, that the Awami Party was not of any substantial help to Bangladesh’s Hindus, for example, when violence was unleashed on them by sections of the majority community. In fact some elements in the Awami Party were found to be siding with the Hindus’ murderous persecutors. Such are the temptations of hard line majoritarianism.

In Sri Lanka’s past numerous have been the occasions when even self-professed Leftists and their parties have conveniently fallen in line with Southern nationalist groups with self-interest in mind. The present NPP government in Sri Lanka has been waxing lyrical about fostering national reconciliation and harmony but it is yet to prove its worthiness on this score in practice. The NPP government remains untested material.

As a first step towards national reconciliation it is hoped that Sri Lanka’s present rulers would learn the Tamil language and address the people of the North and East of the country in Tamil and not Sinhala, which most Tamil-speaking people do not understand. We earnestly await official language reforms which afford to Tamil the dignity it deserves.

An acid test awaits Bangladesh as well on the nation-building front. Not only must all forms of chauvinism be shunned by the incoming rulers but a secular, truly democratic Bangladesh awaits being licked into shape. All identity barriers among people need to be abolished and it is this process that is referred to as nation-building.

On the foreign policy frontier, a task of foremost importance for Bangladesh is the need to build bridges of amity with India. If pragmatism is to rule the roost in foreign policy formulation, Bangladesh would place priority to the overcoming of this challenge. The repatriation to Bangladesh of ex-Prime Minister Hasina could emerge as a steep hurdle to bilateral accord but sagacious diplomacy must be used by Bangladesh to get over the problem.

A reply to N.A. de S. Amaratunga

A response has been penned by N.A. de S. Amaratunga (please see p5 of ‘The Island’ of February 6th) to a previous column by me on ‘ India shaping-up as a Swing State’, published in this newspaper on January 29th , but I remain firmly convinced that India remains a foremost democracy and a Swing State in the making.

If the countries of South Asia are to effectively manage ‘murderous terrorism’, particularly of the separatist kind, then they would do well to adopt to the best of their ability a system of government that provides for power decentralization from the centre to the provinces or periphery, as the case may be. This system has stood India in good stead and ought to prove effective in all other states that have fears of disintegration.

Moreover, power decentralization ensures that all communities within a country enjoy some self-governing rights within an overall unitary governance framework. Such power-sharing is a hallmark of democratic governance.

Features

Celebrating Valentine’s Day …

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Merlina Fernando (Singer)

Yes, it’s a special day for lovers all over the world and it’s even more special to me because 14th February is the birthday of my husband Suresh, who’s the lead guitarist of my band Mission.

We have planned to celebrate Valentine’s Day and his Birthday together and it will be a wonderful night as always.

We will be having our fans and close friends, on that night, with their loved ones at Highso – City Max hotel Dubai, from 9.00 pm onwards.

Lorensz Francke (Elvis Tribute Artiste)

On Valentine’s Day I will be performing a live concert at a Wealthy Senior Home for Men and Women, and their families will be attending, as well.

I will be performing live with romantic, iconic love songs and my song list would include ‘Can’t Help falling in Love’, ‘Love Me Tender’, ‘Burning Love’, ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’, ‘The Wonder of You’ and ‘’It’s Now or Never’ to name a few.

To make Valentine’s Day extra special I will give the Home folks red satin scarfs.

Emma Shanaya (Singer)

I plan on spending the day of love with my girls, especially my best friend. I don’t have a romantic Valentine this year but I am thrilled to spend it with the girl that loves me through and through. I’ll be in Colombo and look forward to go to a cute cafe and spend some quality time with my childhood best friend Zulha.

JAYASRI

Emma-and-Maneeka

This Valentine’s Day the band JAYASRI we will be really busy; in the morning we will be landing in Sri Lanka, after our Oman Tour; then in the afternoon we are invited as Chief Guests at our Maris Stella College Sports Meet, Negombo, and late night we will be with LineOne band live in Karandeniya Open Air Down South. Everywhere we will be sharing LOVE with the mass crowds.

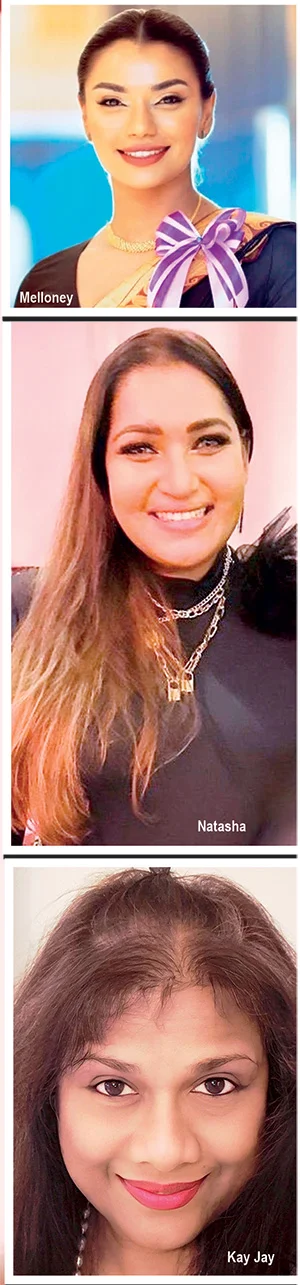

Kay Jay (Singer)

I will stay at home and cook a lovely meal for lunch, watch some movies, together with Sanjaya, and, maybe we go out for dinner and have a lovely time. Come to think of it, every day is Valentine’s Day for me with Sanjaya Alles.

Maneka Liyanage (Beauty Tips)

On this special day, I celebrate love by spending meaningful time with the people I cherish. I prepare food with love and share meals together, because food made with love brings hearts closer. I enjoy my leisure time with them — talking, laughing, sharing stories, understanding each other, and creating beautiful memories. My wish for this Valentine’s Day is a world without fighting — a world where we love one another like our own beloved, where we do not hurt others, even through a single word or action. Let us choose kindness, patience, and understanding in everything we do.

Janaka Palapathwala (Singer)

Janaka

Valentine’s Day should not be the only day we speak about love.

From the moment we are born into this world, we seek love, first through the very drop of our mother’s milk, then through the boundless care of our Mother and Father, and the embrace of family.

Love is everywhere. All living beings, even plants, respond in affection when they are loved.

As we grow, we learn to love, and to be loved. One day, that love inspires us to build a new family of our own.

Love has no beginning and no end. It flows through every stage of life, timeless, endless, and eternal.

Natasha Rathnayake (Singer)

We don’t have any special plans for Valentine’s Day. When you’ve been in love with the same person for over 25 years, you realise that love isn’t a performance reserved for one calendar date. My husband and I have never been big on public displays, or grand gestures, on 14th February. Our love is expressed quietly and consistently, in ordinary, uncelebrated moments.

With time, you learn that love isn’t about proving anything to the world or buying into a commercialised idea of romance—flowers that wilt, sweets that spike blood sugar, and gifts that impress briefly but add little real value. In today’s society, marketing often pushes the idea that love is proven by how much money you spend, and that buying things is treated as a sign of commitment.

Real love doesn’t need reminders or price tags. It lives in showing up every day, choosing each other on unromantic days, and nurturing the relationship intentionally and without an audience.

This isn’t a judgment on those who enjoy celebrating Valentine’s Day. It’s simply a personal choice.

Melloney Dassanayake (Miss Universe Sri Lanka 2024)

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I’m incredibly blessed because, for me, every day feels like Valentine’s Day. My special person makes sure of that through the smallest gestures, the quiet moments, and the simple reminders that love lives in the details. He shows me that it’s the little things that count, and that love doesn’t need grand stages to feel extraordinary. This Valentine’s Day, perfection would be something intimate and meaningful: a cozy picnic in our home garden, surrounded by nature, laughter, and warmth, followed by an abstract drawing session where we let our creativity flow freely. To me, that’s what love is – simple, soulful, expressive, and deeply personal. When love is real, every ordinary moment becomes magical.

Noshin De Silva (Actress)

Valentine’s Day is one of my favourite holidays! I love the décor, the hearts everywhere, the pinks and reds, heart-shaped chocolates, and roses all around. But honestly, I believe every day can be Valentine’s Day.

It doesn’t have to be just about romantic love. It’s a chance to celebrate love in all its forms with friends, family, or even by taking a little time for yourself.

Whether you’re spending the day with someone special or enjoying your own company, it’s a reminder to appreciate meaningful connections, show kindness, and lead with love every day.

And yes, I’m fully on theme this year with heart nail art and heart mehendi design!

Wishing everyone a very happy Valentine’s Day, but, remember, love yourself first, and don’t forget to treat yourself.

Sending my love to all of you.

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Midweek Review4 days ago

Midweek Review4 days agoA question of national pride

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Midweek Review4 days ago

Midweek Review4 days agoTheatre and Anthropocentrism in the age of Climate Emergency