Midweek Review

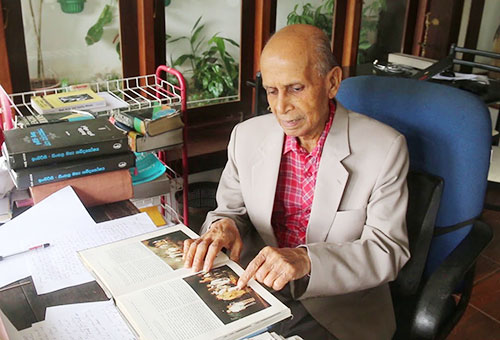

Prof.Carlo Fonseka and freedom of will

First death anniversary

By Dr. H.D.Goonetilleke

(dguna2@gmail.com)

Today, marks the first death anniversary of Prof. Carlo Fonseka, a great intellect and well-known physician, who is also fondly remembered by members of the Rationalist Association of Sri Lanka as one of its founding members. He wrote regularly to this newspaper, trying to promote rational thinking among all his fellow citizens. Here, in memory of Carlo’s lifelong commitment to seek rationality and reason in every aspect of his life, I wish to relate an instance of him trying to stimulate one’s own thinking and reasoning to counter one of the most convincing illusions we harbour – the illusion of ‘Free Will’.

Although I did not know him personally when I went to see his exploits in fire-walking at Attidiya in the early 70s, I came to know him closely many years later, having the occasion to talk to him at length on various matters. In one such conversation I had at his home, a few years before his death, he said to me that modern science was enabling us to link and associate human cognitive functions directly with different regions of the brain. However, he said that of the five main attributes of thinking, feeling, perceiving, memorizing and willing of human conduct, only the first four can be correlated precisely with any kind of neuronal activity of the brain. There seems to be no part of the brain engaged in the apparent act of ‘willing’, or actual decision making carried out by humans at any time.

Carlo was convinced that there is no ‘free will’ or freedom of choice in any decision we make, and he encouraged me to explore it further. He elaborated his position further by quoting 19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer;

“A man can do what he wills, but he cannot ‘will’ what he wills.”

Here, Schopenhauer was commenting on the illusory nature of free will.

As human beings capable of rational thought and self-reflection, we imagine ourselves to have ‘free will’ which makes us distinct from inanimate objects and animals. We believe that ‘we can do what we want’ and be the masters of our own destinies. But sadly for us, the humans, this is just a mental illusion. An illusion so powerful that we are compelled to believe that we have the ability to choose our own actions and be the sole creators of our own behaviour.

For example, you might believe that the reason why you are reading this article now is a free and conscious decision made by you, or your brain, sometime before you started reading it. Sure enough, you are clearly conscious of your initial resolve or the will to read this, but that desire or will was not free from all precursor conditions and circumstances which caused you to read this in the first place. Your ability to act with a conscious desire to read this, or to act with a will should not be confused with your ability to act out of free will, a will that arises ‘uncaused’ in your mind.

Similarly, in a simple choice task of (say) picking an item for dessert you may either quite promptly, or after some careful consideration, choose to eat a fruit rather than an ice-cream. What made you choose the fruit, you might ask. The answer is that as biological beings you and your brain – the organ that does the ‘choosing’-are all made of cells and neurons which are the products of both the genes you have inherited and your environment. All the atoms and molecules that make up your genes and the environment, which also includes everybody and everything else, must obey the laws of physics and behave according to such laws. The behaviour of these atoms and molecules down to the fundamental particles of quarks, leptons and bosons whose interactions are also subject to quantum unpredictability and chance, eventually makes it necessary that you choose a fruit, and not an ice-cream. You really had no role in the choice you made when you picked a fruit for dessert. And, it is so with everything else you say or do during any of the waking hours.

It appears that there are countless number of causal chains and events that influence all our decisions and actions leaving no room for us to make any choice independently. As social psychologist Joachim Krueger of Brown University puts it the totality of the natural causal forces in play generating ‘necessity’, along with random variations not reducible to causes adding an element of ‘chance’, dictate everything in the universe including human behaviour. If the notion of free will exists, it claims a special place for human conduct that is not governed by either necessity or chance, but by an ‘uncaused will’ that fundamentally violates the principle of cause and effect.

Neuroscientists studying how the brain works with latest imaging technologies such as EEG, fMRI and PET Scans also support the idea that free will is a complete illusion. Using computer aided mapping of brain activity, they have been able to predict the decisions made by their subjects a few seconds before actual choices are made by them, indicating the presence of unconscious processes prior to reaching their decisions. The unambiguous conclusion of these experimental observations is that if a choice is made well before the moment you think you made it; you cannot claim to have free will in any meaningful way.

However, many people find the illusion of free will an alarming prospect as it brings to question the individual moral responsibility. If there is no free will how can we judge people as moral or immoral? Why punish criminals for their crimes if their actions are not freely chosen? Evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne at University of Chicago suggests that although the will is not free it must be perceived as such, in order to maintain social order and harmony. Even in the absence of free will punishment and reward can be used to deter bad behavior and promote good behavior by causally influencing the minds of people.

The realisation that free will is a mental illusion like an optical illusion could bring about profound psychological and emotional implications for many, deeply affecting the way we think about ourselves – as autonomous or automatons. However, one can take consolation by the fact that we are no more special or different from any other object in the universe. By recognizing that there is no ‘I’ which can say “I could have done otherwise” we realize that in the end all of us are victims of circumstances. As Carlo put it, by losing free will and gaining empathy towards others who too cannot act on their own free will, we can go about building a kinder world.