Features

Probably most brilliant officer the Army ever had

Lt Col PVJ (Jayantha) de Silva, SL Light Infantry (1941-2023):

Maj. Gen. (Retd.) Lalin Fernando

“Do not stand at my grave and cry; I am not there; I did not die”

Late Lt Col PVJ (Jayantha) de Silva, Sri Lanka Light Infantry, (the oldest regiment in the Army – raised in 1881), served in the SL Army from 1964 to 1987.He sadly passed away in Australia after a fall just short of his 80th birthday.

He was probably the most brilliant officer the Army ever had; some say even a genius. He was also an unwavering, staunch, stubborn patriot as he was unforgiving of those, military or political who faltered. I admired him. He was my very good friend.

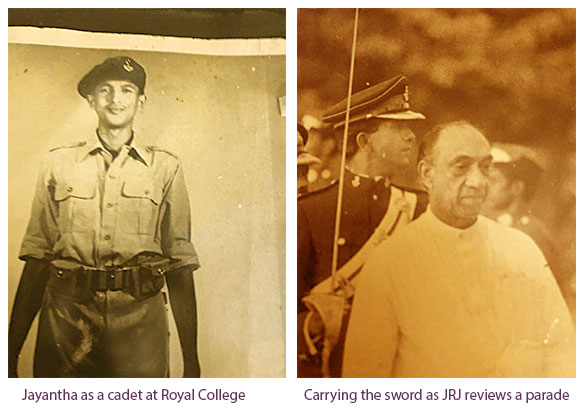

Educated at Royal College where he was prefect and Cadet Sergeant, he was also a national basketball player. He was in the first intake of five officer cadets to the Pakistan Military Academy in Kakul in 1964. He, showing extraordinary leadership potential to prove himself among Pakistani cadets from the famed martial races of Punjabis, Pathans and Baluchis being appointed Battalion Junior Under Officer in his final term. He was the first and only one from Ceylon (SL) to be so appointed on the regular long course of two and a half years (It is now a two-year course).

He came third (of over 200 cadets) in the order of merit. The others in the Ceylon intake of five included Srilal Weerasuriya, later General and Army Commander. He later graduated from the Indian Staff College, Wellington, being recommended for Operations and Training, the plum posting for the best achievers. He was excellent in the field and on the staff.

I came across some of his Light Infantry soldiers in Talaimannar on a search operation when on Anti Illicit Immigration duties in the late 1960s. They spoke with pride of their lean, six-foot-tall whipcord strong, platoon commander’s successes. Clearly, he had looked after their every need as indeed the regimental motto “Ich Dien” (I serve) expected him to do – to serve his men. Many senior officers in a politicized army do not understand the motto believing ‘I serve’ means serve politicians!

Jayantha’s extraordinary feats were many and legendary. When the Russians gifted 82 mm mortars after the 1971 JVP Insurgency, Jayantha was the leader of the army infantry team of officers and sergeants chosen to be instructed on the weapon. The Russians took the whole of the first day to introduce the new weapon in the belief that the locals had to learn from scratch probably unaware we were well trained on the British three-inch mortars albeit of WW 2 origin.

At the end of the first day Jayantha asked the bemused Russians to take the next day off. He asked the infantry team to assemble at the Panaluwa range the next morning. The team was taught everything about the weapon including how to fire it by Jayantha. The following morning the Russians were taken to the firing range instead of the weapon training area. The sections of the team then demonstrated the dismantling and assembling of the mortar.

The Russians were next taken to the field firing range where the mortar bombs (shells) were fired. The planned six-week course was over! That was PVJ.

When his SLLI commanding officer Lt Col (later Major General) HV (Henry) Athukorale wanted a regimental museum, he created one almost overnight. He was entrusted with revising the Regimental Standing Orders. When Military Assistant (MA) to the Commander of the Army, Lt Gen Denis Perera, he produced the most comprehensive Army Dress Regulations. All in quick time.

I remember Jayantha as the first ever MA to an Army Commander (Maj Gen Denis Perera) accompanying the Commander on the first of the Army Commander’s bi-annual Inspection team at HQ Task Force One at Pallaly (Jaffna). In the evening at the Officers’ Mess the mood was convivial with the gift of two bottles of whiskey from the Commander helping; but Jayantha was missing.

The next morning as the Commander and his staff left for the airport the Minutes of the inspection, accurate and critical with action to be taken, would be in my hands. This speed of response upset some commanding officers (who complained). They were used to ambling along previously. Now their command deficiencies were pinpointed. The Army was in a resurgent era.

At the Non-Aligned Conference held in Colombo, about 100 heads of state or government, attended. They had each to be given a Guard of Honour at Katunayake whatever time they arrived. Their arrivals were within a short intervals of each other. Jayantha was Deputy to Brig TI Weeratunge (later Army Commander). Brig Weeratunge had time on his hands as Jayantha had organized rehearsals, timings and dress inspections with passion. The ceremonials were outstanding.

The VVIPs arriving included Mrs. Indira Gandhi, Sadat, Makarios (Cyprus), Hafiz al Assad and the eccentric Libyan leader Gaddafi. Marshal Tito arrived in his yacht in the Colombo harbour.

As Commandant of the Combat Training School in Ampara he revamped it entirely. Everything from theory lessons, conduct of field tactical exercises and Standard Operating Procedures were in writing. His successors had only to follow them.

While SL was laboring to match the terrorists early lead in technology, it was to Jayantha that the Army Commander turned to build SL’s first indigenous Armoured Personnel Carrier (APC) with a V shaped hull. It proved to be far superior against mines to the imported, much acclaimed South African APC. He did so with a team of technicians from the Electrical and Mechanical Engineers at their Colombo workshop. And he was just an infantry officer.

Had Jayantha remained in the Army instead of emigrating, he would have worked wonders with technology but he had no far thinking Gen Sundarji (brilliant Indian Chief of Army Staff and the only infantry officer to command the First Indian Armoured Division too) or any brass hat to back him in an unsophisticated army given to sycophancy and later even commanded by one who gifted weapons and ammo to the terrorists.

He could have given the Army a lead in AI too. Instead, his inputs were apparently in the Australian Defence Industry. He was last heard providing (unsolicited?) detailed inputs for Australia’s indigenous aircraft carrier. While Sundarji wrote “Blind Men of Hindustan” as his treatise on Indian Nuclear Policy was not too well received, Jayantha wrote a new Constitution for SL that he insisted I read to know how to resolve our problems. I was tactful in responding.

Jayantha had a Kodak camera with which he recorded many events in camp and on training. I requested him to photograph my wedding and gave him a roll of film. He gave me a whole lot of super wedding photos and returned the film as he was wont to do. When years later he found his camera outdated, he searched for the newfangled parts needed to upgrade it. He could not find any. Jayantha then manufactured them and soon had a camera that was uptodate.

He then sent the drawings of his work to many camera companies. Only Kodak responded. They asked whether he had registered for copyrights. He said no. Kodak asked whether they could come to an agreement about producing the parts. He told them there was no need for an agreement and they could just have it. They asked whether they could use his name. He said it was unnecessary as both knew who did the work!

I first met Jayantha when he was an officer cadet in 1964.I was on a Regimental Signals Officer’s course at Rawalpindi. He would come with four other cadets including Srilal Weerasuriya (later General and Commander of the Army) and stay in my officers’ mess quarters during the rare training breaks. They would each bring their bed rolls and lay it out in the sitting room so they had no problem about sleeping.

They also joined four officers (Capts Kamal Fernando and WM Weerasuriya, Lt SJ Weerasena and me to form a ‘Ceylon Army’ cricket team to play GHQ Pakistan. The five cadets were not very impressive cricketers. We were loaned two Pakistani officers who were not any better. We lost. They had a national player who had just played against the MCC. He scored a century.

The next time we met was in mid-1968 was when we were both appointed Instructors for the first ever Officer Cadets course held in SL at the Officer Cadet School (now the SL Military Academy) at the Army Training Center (ATC) Diyatalawa. We replaced the two instructors who had been there during the first term. This was a most rewarding posting ever as we were in charge of not just new officer cadets but of the promise of the army’s future. This intake, initially of 12, was incomparable.

We were very fortunate that Lt Col (later General and Commander of the Army from the first Ceylon Intake at Sandhurst Denis Perera was first the Deputy (to Col Lyn Wicramasuriya) and then Commandant of the ATC. He ensured that the cadets wanted in nothing. Maj MD Fernando was the Chief Instructor (CI).

We soon discovered that instructor sergeants and sergeant major whose duties were respectively drill and weapons, had been allowed to impose themselves on the cadets in their free time and in the cadets’ mess. A hurried meeting on the first day itself laid down the ground rules. The other rank instructors were told that the accommodation and cadets mess were not in their province and to desist from going there as everything there was the responsibility of Officer instructors alone.

This was a clean break from what had been going on when directly enlisted officers were trained and NCOs ran the roost after close of the days play. Warrant Officer Ahmath (Armoured Corps) was an excellent Wing Sergeant Major.

The cadets had been told to start digging a well at the top of the hill overlooking the Halangode Wewa! This was stopped on the first day itself. The foundation, standards, customs and traditions were set initially by the officer instructors. They were handed down inviolate by Intake One who by the time Intake Two and a volunteer force intake of young officers arrived, had matured enough to govern and set the pattern for the succeeding intakes. The term Beast Billet (for first termers) came into vogue then. Bullying and ragging were not allowed as Intake One had set the standard.

The first three intakes had the founder commander of the Commandos and two Army Commanders including SL’s only Field Marshal and a rifle shooting Olympian who twice contested!

Field training exercises were talked about long after they ended. The first initiative exercise was held in the Passara hills with planters being ‘friendly collaborators’ of ‘cadet saboteurs’, then in Ampara in a tropical thunderstorm at night that made the cadets think the exercise would be called off. It wasn’t. The two instructors accompanied each ‘sabotage’ patrol across flooded paddies and raging torrents near the airport. The third was in Trincomalee.

Conventional warfare exercises were held on Fox Hill, in Gurutalawa and Horton Plains. Jungle training was carried out in the South Eastern jungles off Kuda Oya by the British Far East Jungle Warfare School Malaya-trained Capt (later Major General) Wijaya Wimalaratne and Warrant Officer Jayasinghe, both from Gemunu Watch.

On parade Warrant Officer Dayananda, (Armoured Corps) trained at the Brigade of Guards Drill Depot Pirbright, UK) never failed to say after each rehearsal for the Commissioning parade that every officer must try to match Jayantha’s sword drill standard – that included the parade commander- me!

The rugby team with a galaxy of schoolboy players in Intake Three won the Clifford Cup C Division the first time it entered.

Jayantha had the very best leadership characteristics starting from unshakable integrity, physical and moral courage, in depth knowledge of his profession including its technical side, initiative, was lightning fast in taking decisions and implementing them. He was fair and just in all his dealings. He was straight, unafraid to speak his mind but not haughty or arrogant, pleasant mannered and adaptive, lean and hard, highly motivated and disciplined. He never spoke of race or religion in the best traditions of the Army. He was first class at everything he had to do in the Army except for playing cricket. He was a true friend and loyal.

He had little patience, never gossiped, was firm, hardly merciful, was uncompromising and not very flexible. When asked by a retired Army commander visiting Australia why he did not want to meet him (the former commander), he said simply ‘You saluted the terrorists’ (during the 2001-3 phony Norwegian sponsored peace initiative).

The question must then be asked why an outstanding mid ranking officer whose early promise blossomed throughout his career abruptly decided to quit the army and migrate to Australia as a Lt Col, when achieving the highest command rank was a probability. Clearly in SL it was not. I cannot think of any army other than SL’s where such an exceptional officer would have been allowed to go without an effort to retain him. Was there an exit interview? I doubt it as at that time the army had lost a lot of its confidence and a few army commanders had openly said the war could not be won, shamelessly contradicting their own appointments.

One had secretly followed treacherous orders and arranged weapons and ammo plus cash in dollars and cement to be given to the LTTE on the treasonable orders of a Commander-in Chief!

As for career planning it appeared that was in the hands of politicians. Shocking debacles followed. Thousands died. No senior commander was punished. Many were promoted. Sadly, it appeared that the deaths of thousands of soldiers and young officers mattered less than the need to protect the guilty Generals.

A guilty conscience pervaded the upper ranks. They did not in many cases serve their men. By 2006 the lessons were well learned, the surviving fighting elements had been to hell and back for decades They were ready to finish it off. They did so with a political leadership that for once made sure the Army and the forces in general lacked nothing to win the conflict.

Jayantha had not been given command of his battalion despite being the most outstanding mid ranking officer not only in his regiment but also in the army to deserve it. When asked, two former Army Commanders, one his intake mate to the Pakistan Military Academy and the other who he had trained, thought it was due to the fact that Jayantha’s last two bosses as Army Commanders (1981-88) made prolific use of his amazing grasp of technology for the army rather than release him to command his regiment, the vital starting point of higher command. This could have happened only in the SL Army as any career plan had to give command of one’s own regiment the highest priority.

It is probable that in many other armies a similar talent would have seen the incumbent given a double promotion straight to Brigadier. All this was not to be. In my humble opinion, had Jayantha stayed on he would have made the best and most effective and successful Army commander albeit in his time, after Gen Denis Perera.

On a personal note, I remember going with my family to Kandy for the Perahera. Jayantha who was the senior staff officer in Central, Command made all the arrangements for our stay. At night he saw that only my elder daughter and I were going out as my wife would stay with our two-year old second daughter. He immediately said he would look after the baby and asked for instructions. On our return about midnight, we saw Jayantha with a pen light torch reading a book having prepared and given the baby her milk on time. In his spare time Jayantha coached the Trinity College basketball team.

When Jayantha left SL, the Army lost her most talented officer, his friends lost a wonderful and close friend. His death in Australia came as a shock to all. The saddest part was that we in SL were sure he would outlive all of us even as most of us had not seen him for nearly 35 years; but he never forgot SL, the Army and us and kept our morale up during the darkest days of the conflict with his unrelenting confidence in final victory.

He will be much missed by all who knew him. May his stay in Samsara be short. He leaves his wife Chintha, daughter Piyumali and son Suresh.

Note

Intake one had the head prefects of Royal, S Thomas’, Kingswood and St John’s, Jaffna, the cricket captain of Ananda and Combined Schools, national rifle firing pool member (and twice future Olympian), three public school athletes, a Nalanda cricketer, vice-captain Royal College rugby, one Royal College rowing team member and a soldier entry who was a national rugby player.

Features

The Great and Little Traditions and Sri Lankan Historiography

Power, Culture, and Historical Memory:

History, broadly defined, is the study of the past. It is a crucial component of the production and reproduction of culture. Studying every past event is neither feasible nor useful. Therefore, it is necessary to be selective about what to study from the countless events in the past. Deciding what to study, what to ignore, how to study, and how deeply to go into the past is a conscious choices shaped by various forms of power and authority. If studying the past is a main element of the production and reproduction of culture and History is its product, can a socially and culturally divided society truly have a common/shared History? To what extent does ‘established’ or ‘authentic’ History reflect the experiences of those remained outside the political, economic, social, and cultural power structures? Do marginalized groups have their own histories, distinct from dominant narratives? If so, how do these histories relate to ‘established’ History? Historiography today cannot ignore these questions, as they challenge the very notion of truth in History. Due to methodological shifts driven by post-positivist critiques of previously accepted assumptions, the discipline of history—particularly historiography—has moved into a new epistemological terrain.

The post-structuralism and related philosophical discourses have necessitated a critical reexamination of the established epistemological core of various social science disciplines, including history. This intellectual shift has led to a blurring of traditional disciplinary boundaries among the social sciences and the humanities. Consequently, concepts, theories, and heuristic frames developed in one discipline are increasingly being incorporated into others, fostering a process of cross-fertilization that enriches and transforms scholarly inquiry

In recent decades, the discipline of History has broadened its scope and methodologies through interactions with perspectives from the Social Sciences and Humanities. Among the many analytical tools adopted from other disciplines, the Great Tradition and Little Tradition have had a significant impact on historical methodology. This article examines how these concepts, originally developed in social anthropology, have been integrated into Sri Lankan historiography and assesses their role in deepening our understanding of the past.

The heuristic construct of the Great and Little Traditions first emerged in the context of US Social Anthropology as a tool/framework for identifying and classifying cultures. In his seminal work Peasant society and culture: an anthropological approach to civilization, (1956), Robert Redfield introduced the idea of Great and Little Traditions to explain the dual structure of cultural expression in societies, particularly in peasant communities that exist within larger civilizations. His main arguments can be summarized as follows:

a) An agrarian society cannot exist as a fully autonomous entity; rather, it is just one dimension of the broader culture in which it is embedded. Therefore, studying an agrarian society in isolation from its surrounding cultural context is neither possible nor meaningful.

b) Agrarian society, when views in isolation, is a ‘half society’, representing a partial aspect/ one dimension of the broader civilization in which it exits. In that sense, agrarian civilization is a half civilization. To fully understand agrarian society—and by extension, agrarian civilization—it is essential to examine the other half that contribute to the whole.

c) Agrarian society was shaped by the interplay of two cultural traditions within a single framework: the Great Tradition and the Little Tradition. These traditions together provided the unity that defined the civilization embedded in agrarian society.

d) The social dimensions of these cultural traditions would be the Great Society and the Little Society.

e) The Great Culture encompasses the cultural framework of the Great Society, shaped by those who establish its norms. This group includes the educated elite, clergy, theologians, and literati, whose discourse is often regarded as erudite and whose language is considered classical.

f) The social groups excluded from the “Great Society”—referred to as the “Little Society”—have their own distinct traditions and culture. The “Great Tradition” represents those who appropriate society’s surplus production, and its cultural expressions reflect this dominance. In contrast, the “Little Tradition” belongs to those who generate surplus production. While the “Great Tradition” is inherently tied to power and authority, the “Little Tradition” is not directly connected to them.

g) According to Robert Redfield, the Great and Little Traditions are not contradictory but rather distinct cultural elements within a society. The cultural totality of peasant society encompasses both traditions. As Redfield describes, they are “two currents of thought and action, distinguishable, yet overflowing into and out of each other.” (Redfield, 1956).

At the time Redfield published his book Peasant Society and Culture: an Anthropological Approach to Civilization (1956), the dominant analytical framework for studying non-Western societies was modernization theory. This perspective, which gained prominence in the post-World War II era, was deeply influenced by the US geopolitical concerns. Modernization theory became a guiding paradigm shaping research agendas in anthropology, sociology, political science, and development studies in US institutions of higher learning,

Modernization theory viewed societies as existing along a continuum between “traditional” and “modern” stages, with Western industrialized nations positioned near the modern end. Scholars working within this framework argued that economic growth, technological advancement, urbanization, and the rationalization of social structures drive traditional societies toward modernization. The theory often emphasized Western-style education, democratic institutions, and capitalist economies as essential components of this transition.

While engaging with aspects of modernization theory, Redfield offered a more nuanced perspective on non-Western societies. His concept of the “folk-urban continuum” challenged rigid dichotomies between tradition and modernity, proposing that social change occurs through complex interactions between rural and urban ways of life rather than through the simple replacement of one by the other.

The concepts of the Great and Little Traditions gained prominence in Sri Lankan social science discourse through the works of Gananath Obeyesekere, the renowned sociologist who recently passed away. In his seminal research essay, The Great Tradition and the Little in the Perspective of Sinhalese Buddhism (Journal of Asian Studies, 22, 1963), Gananath Obeyesekere applied and adapted this framework to examine key aspects of Sinhalese Buddhism in Sri Lanka. While Robert Redfield originally developed the concept in the context of agrarian societies, Obeyesekere employed it specifically to analyze Sinhala Buddhist culture, highlighting significant distinctions between the two approaches.

He identifies a phenomenon called ‘Sinhala Buddhism’, which represents a unique fusion of religious and cultural traditions: the Great Tradition (Maha Sampradaya) and the Little Traditions (Chuula Sampradaya). To fully grasp the essence of Sinhala Buddhism, it is essential to understand both of these dimensions and their interplay within society.

The Great Tradition represents the formal, institutionalized aspect of Buddhism, centered on the Three Pitakas and other classical doctrinal texts and commentaries of Theravāda Buddhism. It embodies the orthodoxy of Sinhala Buddhism, emphasizing textual authority, philosophical depth, and ethical conduct. Alongside this exists another dimension of Sinhala Buddhism known as the Little (Chuula) Tradition. This tradition reflects the popular, localized, and ritualistic expressions of Buddhism practiced by laypeople. It encompasses folk beliefs, devotional practices (Bali, Thovil), deity veneration, astrology, and rituals (Hadi and Huunium) aimed at securing worldly benefits. Unlike the doctrinally rigid Great Tradition, the Little Tradition is fluid, adaptive, and shaped by indigenous customs, ancestral practices, and even elements of Hinduism. These Sinhala Buddhist cultural practices are identified as ‘Lay-Buddhism’. Gananath Obeyesekera’s concepts and perspectives on Buddhist culture and society contributed to fostering an active intellectual discourse in society. However, the discussion on the concept of Great and Little Traditions remained largely within the domain of social anthropology.

The scholarly discourse on the concepts of Great and Little Tradition gained new socio-political depth through the work of Newton Gunasinghe, a distinguished Sri Lankan sociologist. He applied these concepts to the study of culture and socio-economic structures in the Kandyan countryside, reframing them in terms of production relations. Through his extensive writings and public lectures, Gunasinghe reinterpreted the Great and Little Tradition framework to explore the interconnections between economy, society, and culture.

Blending conventional social anthropology approach with Marxist analyses of production relations and Gramscian perspectives on culture and politics, he offered a nuanced understanding of these dynamics. In the context of our discussion, his key insights on culture, society, and modes of production can be summarized as follows.

a. The social and economic relations of the central highlands under the Kandyan Kingdom, the immediate pre-colonial social and economic order, were his focus. His analysis did not cover to the hydraulic Civilization of Sri Lanka.

b. He explored the organic and dialectical relationship between culture, forces of production, and modes of production. Drawing on the concepts of Antonio Gramsci and Louis Althusser, he examined how culture, politics, and the economy interact, identifying the relationship between cultural formations and production relations

c. Newton Gunasinghe’s unique approach to the concepts of Great Culture and Little Culture lies in his connection of cultural formations to forces and relations of production. He argues that the relationship between a society’s structures and its superstructures is both dialectical and interpenetrative.

d. He observed that during the Kandyan period, the culture associated with the Little Tradition prevailed, rather than the culture linked to the Great Tradition.

e. The limitations of productive forces led to minimal surplus generation, with a significant portion allocated to defense. The constrained resources sustained only the Little Tradition. Consequently, the predominant cultural mode in the Kandyan Kingdom was, broadly speaking, the Little Tradition.

(To be continued)

by Gamini Keerawella

Features

Celebrating 25 Years of Excellence: The Silver Jubilee of SLIIT – II

Founded in 1999, with its main campus in Malabe and multiple centres across the country—including Metro Campus (Colombo), Matara, Kurunegala, Kandy (Pallekele), and Jaffna (Northern Uni)—SLIIT provides state-of-the-art facilities for students, now celebrating 25 years of excellence in 2025.

Founded in 1999, with its main campus in Malabe and multiple centres across the country—including Metro Campus (Colombo), Matara, Kurunegala, Kandy (Pallekele), and Jaffna (Northern Uni)—SLIIT provides state-of-the-art facilities for students, now celebrating 25 years of excellence in 2025.

Kandy Campus

SLIIT is a degree-awarding higher education institute authorised and approved by the University Grants Commission (UGC) and Ministry of Higher Education under the University Act of the Government of Sri Lanka. SLIIT is also the first Sri Lankan institute accredited by the Institution of Engineering & Technology, UK. Further, SLIIT is also a member of the Association of Commonwealth Universities (ACU) and the International Association of Universities (IAU).

Founded in 1999, with its main campus in Malabe and multiple centres across the country—including Metro Campus (Colombo), Matara, Kurunegala, Kandy (Pallekele), and Jaffna (Northern Uni)—SLIIT provides state-of-the-art facilities for students, now celebrating 25 years of excellence in 2025.

Since its inception, SLIIT has played a pivotal role in shaping the technological and educational landscape of Sri Lanka, producing graduates who have excelled in both local and global arenas. This milestone is a testament to the institution’s unwavering commitment to academic excellence, research, and industry collaboration.

Summary of SLIIT’s

History and Status

Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology (SLIIT) operates as a company limited by guarantee, meaning it has no shareholders and reinvests all surpluses into academic and institutional development.

* Independence from Government: SLIIT was established in 1999 as an independent entity without government ownership or funding, apart from an initial industry promotion grant from the Board of Investment (BOI).

* Mahapola Trust Fund Involvement & Malabe Campus: In 2000, the Mahapola Trust Fund (MTF) agreed to support SLIIT with funding and land for the Malabe Campus. In 2015, SLIIT fully repaid MTF with interest, ending financial ties.

* True Independence (2017-Present): In 2017, SLIIT was officially delisted from any government ministry, reaffirming its status as a self-sustaining, non-state higher education institution.

Today, SLIIT is recognised for academic excellence, global collaborations, and its role in producing IT professionals in Sri Lanka

.A Journey of Growth and Innovation

SLIIT began as a pioneering institution dedicated to advancing information technology education in Sri Lanka. Over the past two and a half decades, it has expanded its academic offerings, establishing itself as a multidisciplinary university with programmess in engineering, business, architecture, and humanities, in addition to IT. The growth of SLIIT has been marked by continuous improvement in infrastructure, faculty development, and curriculum enhancement, ensuring that students receive world-class education aligned with industry needs.

Looking Ahead: The Next 25 Years

As SLIIT celebrates its Silver Jubilee, the institution looks forward to the future with a renewed commitment to excellence. With advancements in technology, the rise of artificial intelligence, and the increasing demand for skilled professionals, SLIIT aims to further expand its academic offerings, enhance research capabilities, and continue fostering a culture of innovation. The next 25 years promise to be even more transformative, as the university aspires to make greater contributions to national and global progress.

Sports Achievements:

A Legacy of Excellence

SLIIT has not only excelled in academics but has also built a strong reputation in sports. Over the years, the university has actively promoted athletics and competitive sports by organising inter-university and inter-school competitions, fostering a culture of teamwork, discipline, and resilience. SLIIT teams have secured victories in national and inter-university competitions across various sports, including cricket, basketball, badminton, rugby, football, swimming, and athletics. SLIIT’s sports achievements reflect its dedication to holistic student development, encouraging students to excel beyond the classroom.

Kings of the pool!

Once again, our swimmers have brought glory to SLIIT by emerging as champions at the Asia Pacific Institute of Information and Technology Extravaganza Swimming Championship 2024. They won the Men’s, Women’s, and Overall Championships. Congratulations to all swimmers for their dedication and hard work in the pool, bringing honour to SLIIT.

Winning International Competitions

SLIIT students have participated in and excelled in various international competitions, including Robofest, Codefest, and the University of Queensland – Design Solution for Impact Competition, showcasing their skills and talent on a global stage.

Here’s a more detailed look at SLIIT’s involvement in international competitions:

Robofest:

SLIIT’s Faculty of Engineering organises the annual Robofest competition, which aims to empower students with skills in electronics, robotics, critical thinking, and problem-solving, preparing them to compete internationally and bring recognition to Sri Lankan talent.

Codefest:

CODEFEST is a nationwide Software Competition organized by the Faculty of Computing of Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology (SLIIT) geared towards exhibiting the software application design and developing talents of students island-wide. It is an effort of SLIIT to elevate the entire nation’s ICT knowledge to achieve its aspiration of being the knowledge hub in Asia. CODEFEST was first organised in 2012 and this year it will be held for the 8th consecutive time in parallel with the 20th anniversary celebrations of SLIIT.

University of Queensland – Design Solution for Impact Competition:

SLIIT hosted the first-ever University of Queensland – Design Solution for Impact Competition in Sri Lanka, with 16 school teams from across the country participating.

International Open Day:

SLIIT organises an International Open Day where students can connect with distinguished lecturers and university representatives from prestigious institutions like the University of Queensland, Liverpool John Moores University, and Manchester Metropolitan University.

Brain Busters:

SLIIT Brain Busters is a quiz competition organised by SLIIT. The competition is open to students of National, Private and International Schools Island wide. The programme is broadcast on TV1 television as a series.

Inter-University Dance Competition:

SLIIT Team Diamonds for being selected as finalists and advancing to the Grand Finale of Tantalize 2024, the inter-university dance competition organised by APIIT Sri Lanka. The 14 talented team members from various SLIIT faculties have showcased their skills in Team Diamonds and earned their spot as finalists, competing among over 30 teams from state universities, private universities, and higher education institutes.

Softskills+

For the 11th consecutive year, Softskills+ returns with an exciting lineup of events aimed at honing essential soft skills among students. The program encompasses an interschool quiz contest and a comprehensive workshop focused on developing teamwork, problem-solving abilities, leadership qualities, and fostering creative thinking.

Recently, the Faculty of Business at SLIIT organised its annual Inter-school Quiz Competition and Soft Skills Workshop, marking its fifth successive year. Targeting students in grades 11 to 13 from Commerce streams across State, Private, and International schools, the workshop sought to ignite a passion for soft skills development, emphasising teamwork, problem-solving, creativity, and innovative thinking. Recognising the increasing importance of these soft skills in today’s workforce, the programme aims to fill the gap often left unaddressed in the school curriculum.”

The winners of the soft skill competition with Professor Lakshman Rathnayake: Chairman/Chancellor, Vice Chancellor/MD Professor Lalith Gamage, Professor Nimal Rajapakse: Senior Deputy Vice – Chancellor & Provost, Deputy Vice Chancellor – Research and International Affairs Professor Samantha Thelijjagoda, and Veteran Film Director Somarathna Dissanayake.

VogueFest 2024:

SLIIT Business School organised VogueFest 2024, a platform for emerging fashion designers under 30 to showcase their work and win prizes.

T-shirt Design Competition with Sheffield Hallam University:

SLIIT and Sheffield Hallam University (SHU) UK collaborated on a T-shirt designing competition, with a voting procedure to select the best design.

SLIIT’s Got Talent

: The annual talent show, SLIIT’s Got Talent 2024, was held for the 10th consecutive year at the Nelum Pokuna Mahinda Rajapaksa Theatre on 27th September 2024. SLIIT’s Got Talent had the audience energised with amazing performances, showcasing mind-blowing talent by the orchestra and the talented undergraduates from all faculties.

Other events:

* SLIIT also participates in events like the EDUVision Exhibition organised by the Richmond College Old Boys’ Association.

* They hosted the first-ever University of Queensland – Design Solution for Impact Competition in Sri Lanka.

* SLIIT Business School also organised the Business Proposal Competition.

SLIIT Academy:

SLIIT Academy (Pvt.) Ltd. provides industrial-oriented learning experiences for students.

International Partnerships:

SLIIT has strong international partnerships with universities like Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), The University of Queensland (UQ), Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), and Curtin University Australia, providing opportunities for students to study and participate in international events.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT University, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala).

Features

Inescapable need to deal with the past

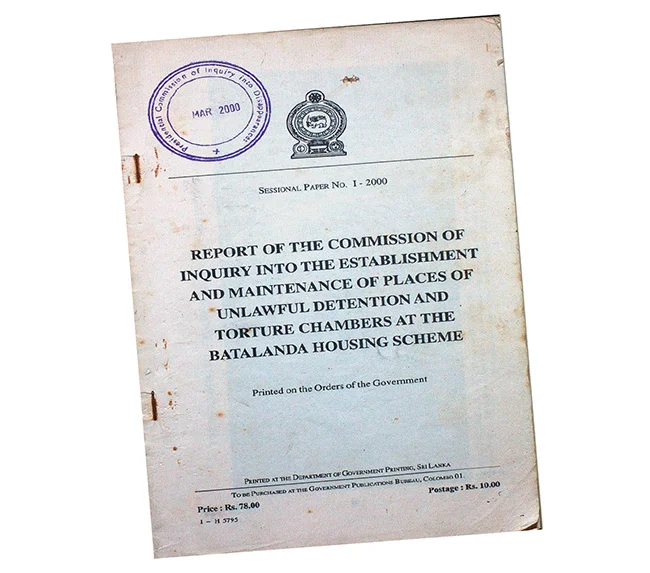

The sudden reemergence of two major incidents from the past, that had become peripheral to the concerns of people today, has jolted the national polity and come to its centre stage. These are the interview by former president Ranil Wickremesinghe with the Al Jazeera television station that elicited the Batalanda issue and now the sanctioning of three former military commanders of the Sri Lankan armed forces and an LTTE commander, who switched sides and joined the government. The key lesson that these two incidents give is that allegations of mass crimes, whether they arise nationally or internationally, have to be dealt with at some time or the other. If they are not, they continue to fester beneath the surface until they rise again in a most unexpected way and when they may be more difficult to deal with.

In the case of the Batalanda interrogation site, the sudden reemergence of issues that seemed buried in the past has given rise to conjecture. The Batalanda issue, which goes back 37 years, was never totally off the radar. But after the last of the commission reports of the JVP period had been published over two decades ago, this matter was no longer at the forefront of public consciousness. Most of those in the younger generations who were too young to know what happened at that time, or born afterwards, would scarcely have any idea of what happened at Batalanda. But once the issue of human rights violations surfaced on Al Jazeera television they have come to occupy centre stage. From the day the former president gave his fateful interview there are commentaries on it both in the mainstream media and on social media.

There seems to be a sustained effort to keep the issue alive. The issues of Batalanda provide good fodder to politicians who are campaigning for election at the forthcoming Local Government elections on May 6. It is notable that the publicity on what transpired at Batalanda provides a way in which the outcome of the forthcoming local government elections in the worst affected parts of the country may be swayed. The problem is that the main contesting political parties are liable to be accused of participation in the JVP insurrection or its suppression or both. This may account for the widening of the scope of the allegations to include other sites such as Matale.

POLITICAL IMPERATIVES

The emergence at this time of the human rights violations and war crimes that took place during the LTTE war have their own political reasons, though these are external. The pursuit of truth and accountability must be universal and free from political motivations. Justice cannot be applied selectively. While human rights violations and war crimes call for universal standards that are applicable to all including those being committed at this time in Gaza and Ukraine, political imperatives influence what is surfaced. The sanctioning of the four military commanders by the UK government has been justified by the UK government minister concerned as being the fulfilment of an election pledge that he had made to his constituents. It is notable that the countries at the forefront of justice for Sri Lanka have large Tamil Diasporas that act as vote banks. It usually takes long time to prosecute human rights violations internationally whether it be in South America or East Timor and diasporas have the staying power and resources to keep going on.

In its response to the sanctions placed on the military commanders, the government’s position is that such unilateral decisions by foreign government are not helpful and complicate the task of national reconciliation. It has faced criticism for its restrained response, with some expecting a more forceful rebuttal against the international community. However, the NPP government is not the first to have had to face such problems. The sanctioning of military commanders and even of former presidents has taken place during the periods of previous governments. One of the former commanders who has been sanctioned by the UK government at this time was also sanctioned by the US government in 2020. This was followed by the Canadian government which sanctioned two former presidents in 2023. Neither of the two governments in power at that time took visibly stronger stands.

In addition, resolutions on Sri Lanka have been a regular occurrence and have been passed over the Sri Lankan government’s opposition since 2012. Apart from the very first vote that took place in 2009 when the government promised to take necessary action to deal with the human rights violations of the past, and won that vote, the government has lost every succeeding vote with the margins of defeat becoming bigger and bigger. This process has now culminated in an evidence gathering unit being set up in Geneva to collect evidence of human rights violations in Sri Lanka that is on offer to international governments to use. This is not a safe situation for Sri Lankan leaders to be in as they can be taken before international courts in foreign countries. It is important for Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and dignity as a country that this trend comes to an end.

COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTION

A peaceful future for Sri Lanka requires a multi-dimensional approach that addresses the root causes of conflict while fostering reconciliation, justice, and inclusive development. So far the government’s response to the international pressures is to indicate that it will strengthen the internal mechanisms already in place like the Office on Missing Persons and in addition to set up a truth and reconciliation commission. The difficulty that the government will face is to obtain a national consensus behind this truth and reconciliation commission. Tamil parties and victims’ groups in particular have voiced scepticism about the value of this mechanism. They have seen commissions come and commissions go. Sinhalese nationalist parties are also highly critical of the need for such commissions. As the Nawaz Commission appointed to identify the recommendations of previous commissions observed, “Our island nation has had a surfeit of commissions. Many witnesses who testified before this commission narrated their disappointment of going before previous commissions and achieving nothing in return.”

Former minister Prof G L Peiris has written a detailed critique of the proposed truth and reconciliation law that the previous government prepared but did not present to parliament.

In his critique, Prof Peiris had drawn from the South African truth and reconciliation commission which is the best known and most thoroughly implemented one in the world. He points out that the South African commission had a mandate to cover the entire country and not only some parts of it like the Sri Lankan law proposes. The need for a Sri Lankan truth and reconciliation commission to cover the entire country and not only the north and east is clear in the reemergence of the Batalanda issue. Serious human rights violations have occurred in all parts of the country, and to those from all ethnic and religious communities, and not only in the north and east.

Dealing with the past can only be successful in the context of a “system change” in which there is mutual agreement about the future. The longer this is delayed, the more scepticism will grow among victims and the broader public about the government’s commitment to a solution. The important feature of the South African commission was that it was part of a larger political process aimed to build national consensus through a long and strenuous process of consultations. The ultimate goal of the South African reconciliation process was a comprehensive political settlement that included power-sharing between racial groups and accountability measures that facilitated healing for all sides. If Sri Lanka is to achieve genuine reconciliation, it is necessary to learn from these experiences and take decisive steps to address past injustices in a manner that fosters lasting national unity. A peaceful Sri Lanka is possible if the government, opposition and people commit to truth, justice and inclusivity.

by Jehan Perera

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAIA Higher Education Scholarships Programme celebrating 30-year journey

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoBid to include genocide allegation against Sri Lanka in Canada’s school curriculum thwarted

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSanctions by The Unpunished

-

Latest News1 day ago

Latest News1 day agoIPL 2025: Rookies Ashwani and Rickelton lead Mumbai Indians to first win

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoMore parliamentary giants I was privileged to know