Midweek Review

Politics of Public Security

By Shamindra Ferdinando

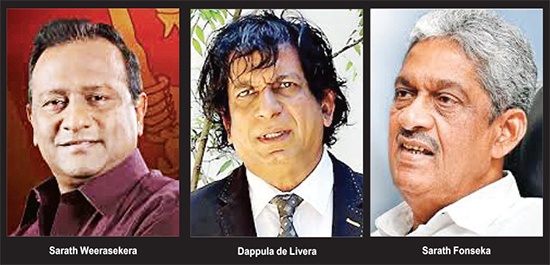

A smiling Public Security Minister, Sarath Weerasekera, MP, (Colombo District), last Thursday (Dec 3), said he was happy to have his school cadet platoon Sergeant Sarath Fonseka, in Parliament as an ordinary MP. The Former Navy Chief of Staff said so in response to Samagi Jana Balavegaya (SJB) lawmaker Fonseka’s reference to Weerasekera being a Corporal in the Ananda College cadet platoon, at the time he served as the Sergeant.

Recently, Viyathmaga member Weerasekera received appointment as the Public Security Minister (formerly Law and Order Minister). Following the parliamentary election in August, Weerasekera received appointment as the State Minister of Provincial Councils and Local Government. Many an eyebrow was raised when one of the strongest critics of the Provincial Council system was named the Minister in charge. Weerasekera gave up the Provincial Council and Local Government Ministry to accept the far more influential Public Security portfolio.

War-winning Army Chief Field Marshal Fonseka and Rear Admiral Weerasekera also exchanged words over the latter’s son, ASP Sachitra Weerasekera, in uniform, saluting the father and then embracing him.

The exchange between Fonseka and Weerasekera highlighted continuing tensions among some sections of the retired top brass, divided on political lines. Both entered Parliament at the 2010 April parliamentary election, the first since the successful conclusion of the war against the LTTE.

Lawmaker Fonseka reiterated accusations directed at Minister Weerasekera in parliament on Monday (7) in the latter’s absence. Weerasekera told the writer that there was absolutely no basis for Fonseka’s assertions and the claim that he received the post of DG, Civil Defence Force with the then Army Commander’s intervention.

Fonseka contested under the Democratic National Alliance (DNA) symbol, having lost badly to Mahinda Rajapaksa, at the 2010 January presidential election, whereas Weerasekera entered Parliament from the Digamadulla district. At the time, the UNP-led political alliance consisting of the TNA, the JVP and the SLMC fielded Fonseka as the common candidate although the Sinha Regiment veteran hadn’t even been registered as a voter anywhere in Sri Lanka at the time.

Along with Fonseka, the JVP-led DNA won seven seats, including two National List slots at the 2010 general election. The DNA group comprised Fonseka (now with Sajith Premadasa’s SJB), Arjuna Ranatunga (still in beleaguered UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe’s camp), Tiran Alles (National List member of the SLPP) and four JVPers. (Today the JVP group consists of three lawmakers – a 50 per cent drop from the previous 2015-2019 Parliament).

Political maneuvering deprived Fonseka of his seat in early Oct 2010. Jayantha Ketagoda, who replaced Fonseka in Parliament, finally ended up in the SLPP National List last August. Politics here is certainly a game of opportunity lacking in any principles.

At the August 2015 general election, Fonseka contested on the Democratic Party ticket. Fonseka led the party, while Ketagoda functioned as his deputy. The DP failed to secure a single seat. In the following year, thanks to UNP leader Wickremesinghe, Fonseka was accommodated on the UNP National List, in the wake of M.K.D.S. Gunawardena’s sudden death.

Before discussing the circumstances leading to the creation of the Public Security Ministry, and elevation of Weerasekera to cabinet rank, it would be pertinent to mention how the naval veteran created history by being the only lawmaker to vote against the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, enacted by yahapalana strategists in early 2015. Weerasekera, in spite of being repeatedly urged to vote for the much-touted piece of legislation, voted against it, whereas almost the entire UPFA grouping, including the Joint Opposition, backed the 19th Amendment.

Weerasekera received public admiration for always taking a tough stand against terrorism, regardless of consequences. Weerasekera risked his naval career during President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s tenure. Weerasekera earned the wrath of the government for resisting LTTE strategies. The then Maj. Gen. Fonseka, too, strongly opposed the LTTE strategy, though the government relentlessly pushed the military to give in. The nation should be eternally grateful to Fonseka for his unwavering stance, in his capacity as Security Forces Commander, Jaffna, to dismantle High Security Zones, in the peninsula. The TNA hated Fonseka so much so that the grouping demanded Fonseka’s removal from the vital Jaffna command, during the 2002-2003 period. Ironically, the TNA and Fonseka, in his capacity as the UNP- backed presidential candidate, reached a marriage of convenience just to oust Rajapaksas in 2010. Again proving that politics is nothing but a game for opportunists in this country, whatever the long term consequences could be.

The unholy alliance that failed to win the 2010 presidential election, succeeded five years later when Maithripala Sirisena defeated Mahinda Rajapaksa, who sought a third presidential term at the expense of political stability. The same alliance, sans the JVP, failed at the 2019 presidential election, to pave the way for wholly new political groups, the SLPP and the SJB to emerge as the main parties. The UNP and the SLFP are irrelevant in today’s context.

Having each served the armed forces, for well over three decades, Fonseka and Weerasekera, now represent the main Opposition (SJB with 54 seats) and the government (145 seats), respectively.

Weerasekera faces a daunting task

There is no point in denying politicization of the police. Successive governments brazenly exploited and abused police, while in return some in the police made hay by often milking the underworld and also getting promotions and perks. The previous yahapalana administration ruined the law enforcement apparatus to such an extent that the police, in spite of having specific foreign intelligence, as regards impending National Thowheed Jamaat (NTJ) strike, allowed the operation to go ahead. At that time of Sri Lanka’s worst security failure, a retired DIG functioned as the Chief of National Intelligence (CNI), a post previously held by veteran intelligence leaders like, then Maj. Gen. Kapila Hendawitharana, one-time head of the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI).

Weerasekera will have to grapple with an extremely dicey situation with two key units – the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) and the Police Narcotic Bureau (PNB) under investigation over serious offenses. In both cases, police headquarters had no option but to hastily remove the DIGs, as well as Directors in charge of the CID and the PNB, pending investigations. Police headquarters is yet to reveal its findings. The PNB is under investigation for dealing in heroin, whereas the CID is under fire for releasing Riyaj Bathiudeen, SJB lawmaker Rishad Bathiudeen’s brother under mysterious circumstances after having been taken into custody under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA).

Previous CID head Shani Abeysekera is now in remand for framing a DIG. He has many other cases in the pipeline against him like fixing cases involving other victims, some of which are on tape him discussing them with actor turned politician Ranjan Ramanayake.

In both the PNB and Riyaj cases, no less a person than intrepid Attorney General Dappula de Livera, PC intervened. The AG demanded special investigation into the CID’s handling of Riyaj Bathiudeen’s case. The President’s Counsel certainly didn’t mince his words when he questioned the deliberate failure on the part of the police to conduct the inquiry and the deliberate denial of the required expertise to bring it to a successful conclusion.

The AG rapped the police in two other cases, namely the Negombo Prison officer’s misconduct and the inordinate delay in the Brandix investigation. In the wake of the Negombo Prison officer’s case, involving the disgraced superintendent of prison Anuruddha Sampayo, the AG called a media briefing, the first time by any AG in over 100 years to take a public stand. On behalf of the AG, Deputy Solicitor General Dileepa Peiris went to the extent of suggesting the deployment of the military to execute arrest warrants if the police found the task too difficult. In the high profile Brandix case, the AG directed an investigation into what his Coordinating Officer State Counsel Nishara Jayaratne called negligence on the part of Brandix, and government officials, in the deadly coronavirus second eruption.

Restoring confidence in law enforcement will certainly be a tough task for the new Minister. The public expected the new administration to take remedial measures. However, the damaging of a section of King Bhuvanekabahu II’s royal pavilion, while demolishing an appendage constructed in more recent times in Kurunegala, in July, on the orders of Kurunegala Mayor Thushara Sanjeewa, bulldozing of a section of the Anavilundawa Ramsar wetland, for shrimp farming, by former Arachchikattuwa Pradeshiya Sabha Chairman Jagath Samantha, brother of State Minister Sanath Nishantha, in September, caused quite a shock.

In the wake of the recent acquittal of former Presidential Secretary Lalith Weeratunga, and the then Director General of the Telecommunication Regulatory Commission Anusha Palpita by the Court of Appeal, in the high profile sil redi case, the focus is now on the police and the Office of the AG. Perhaps there should be a judicial review of the whole process, as successive governments and Oppositions, and vice versa, repeatedly accuse each other of politicizing the judiciary and the police. The nine-member Committee, headed by Romesh de Silva, PC, tasked with formulating a new Constitution, should explore ways and means of having an independent review mechanism.

The Public Security Ministry will have to be mindful of the overall developments, including political environment. Many an eyebrow was raised when Sivenesathurai Chandrakanthan aka Pilleyan, formerly a member of the LTTE fighting cadre, now a lawmaker, who had been arrested in Oct 2015 over his alleged involvement in the assassination of TNA MP Joseph Pararajasingham, in Batticaloa, 10 years before was granted bail after being in remand for about five years over a confession that is not admissible in a court. Chandrakanthan backed the SLPP presidential candidate, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, at the 2019 presidential election. Chandrakanthan also voted for the 20th Amendment to the Constitution. If those who had ordered Chandrakanthan arrested for political reasons, they owed an explanation.

The yahapalana Prime Minister appointed one-time Attorney General Tilak Marapana, PC, as the Law and Order Minister, in Sept 2015. Marapana was accommodated on the UNP National List. The CID arrested Chandrakanthan during Marapana’s short stint as the Law and Order Minister. Marapana resigned in the second week of Nov 2015 over the Avant Garde controversy as he did not see eye to eye with the yahapalana government on that issue like then Minister Wijeyadasa Rajapakse. His resignation paved the way for another Wickremesinghe favourite, Sagala Ratnayake, to assume the Law and Order portfolio. Ratnayake resigned close on the heels of the debilitating setback suffered by the UNP at the Feb 2018 Local Government polls.

Western backed civil society wanted Fonseka

A section of the UNP, as well as the powerful civil society grouping, faulted the Law and Order and Justice Minister Dr. Wijeyadasa Rajapakse, PC for the defeat. They alleged the UNP-led government experienced such a devastating defeat due to their failure to bring high profile cases against the Rajapaksa administration to a successful conclusion. Those who largely found fault with Sagala Ratnayake and Wijeyadasa Rajapakse demanded the appointment of Sarath Fonseka as the Law and Order Minister. President Sirisena, at the UNP’s behest, in mid-August 2017, replaced Wijeyadasa Rajapakse with Thalatha Atukorale. However, President Sirisena flatly refused to accommodate Fonseka as Law and Order Minister. The President’s stand was anyone but Fonseka, who had been harsh on the SLFP leader on many occasions.

The civil society, too, pushed President Sirisena hard to accommodate Fonseka. In the wake of the humiliating defeat suffered by the party, civil society leaders felt the yahapalana arrangement could collapse unless they made a special effort.

Close on the heels of the Feb 10, 2018 defeat, civil society representatives sought assurance from both President Sirisena and Premier Wickremesinghe that they wouldn’t quit the yahapalana alliance over debilitating polls setback. In a bid to pressure the SLFP and UNP leaders, co-conveners of Purawesi Balaya, Gamini Viyangoda, K.W. Janaranjana and Saman Ratnapriya briefed the media as regards their efforts at a hastily arranged media conference at the Centre for Society and Religion (CSR), Maradana on Feb 13, 2018. They acknowledged the possibility of an unceremonious end to the yahapalana arrangement, unless the simmering dispute between the two leaders could be settled. The delegation that made representations to the President and the Premier on Feb 12, 2010, consisted of Ven. Dambara Amila, ‘Annidda’ editor K.W. Janaranjana, Gamini Viyangoda and Saman Ratnapriya. Purawesi Balaya attributed the polls defeat primarily to the yahapalana leaders’ failure to introduce a new Constitution and their failure to punish those responsible for killings and corruption. The writer covered the Purawesi Balaya briefing (Last ditch attempt to prevent collapse of govt – The Island, Feb 14, 2020).

Purawesi Balaya

called a second media briefing on the same matter, on Feb 15, 2020, at the same venue, to demand an immediate solution to the failure on the government’s part to investigate killings and corruption. Amila thera demanded the immediate appointment of Fonseka as the Law and Order Minister. Flanked by Executive Director of the Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) Dr. Pakiasothy Saravanamuttu, Nimalka Fernando, Chameera Perera and Saman Ratnapriya, the yahapalana proponent urged the government to allow the police, under Fonseka, to operate outside what he called democratic norms. Ven. Amila demanded that the police operate beyond normal laws of the land. The openly hardcore right wing monk emphasized that the FCID (Financial Crimes Investigation Division), the CID and other law enforcement arms be placed under Fonseka and the military put on alert. Purawesi Balaya wanted Fonseka given six months to execute the operation. Reiterating their role in Sirisena winning the presidency, the grouping insisted that the yahapalana leaders couldn’t, under any circumstances, abandon the agreed agenda (Prez, PM urged to appoint SF Law & Order Minister – The Island, February 16, 2020).

Rear Admiral Weerasekera wouldn’t have envisaged him receiving the Public Security portfolio as he threw his weight behind the high profile Viyathmaga campaign meant to promote wartime Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa as the SLPP candidate. It would be pertinent to mention that at the time the Viyathmaga campaign got underway, the breakaway UPFA faction hadn’t registered a political outfit of its own.

Sand mining Mafia challenges police

Restoring public confidence in the police would be a herculean task. The police would have to seriously think beyond neutralizing the underworld. Bringing the underworld to its knees is certainly a necessity that needs urgent action. The powerful sand mining Mafia recently killed a 32-year-old policeman, attached to the Bingiriya police station. Although the police quickly arrested the 27-year-old driver of the tipper truck, that ran over the policeman, who signaled him to stop, police headquarters should ensure a proper investigation. Police spokesman Attorney-At-Law DIG Ajith Rohana is on record as having said that the police were deployed to thwart illegal mining at Deduru Oya, on a specific Supreme Court directive. Minister Weerasekera should, without further delay, examine the deteriorating ground situation. High profile case involving former Director of CID SSP Shani Abeysekera, now in remand, custody, fugitive Inspector Nishantha Silva, securing political asylum, in Switzerland, and the arrest of an officer over accusations that he helped the wife of Easter Sunday bomber Hasthun, underscored the need for special attention.

Minister Johnston Fernando, last Saturday (Dec 5) questioned the UNP/SJB, in Parliament over the late Makandure Madush fleeing the country, several years ago. Fernando, onetime UNP heavyweight, who switched his allegiance at the onset of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s first presidential term, alleged a former UNP minister brought the notorious underworld leader on the Southern highway to the Bandaranaike International Airport. Fernando should have named the former minister.

EPDP leader Douglas Devananda recently made a shocking claim in Parliament. One-time militant Devananda, who himself received weapons training, in India, alleged, in Parliament, that a lawmaker, from the Jaffna peninsula, currently serving Parliament, was involved in the abduction and killing of SSP Charles Wijewardena, in Jaffna, during the Ceasefire Agreement. The mainstream media, as well as the social media, conveniently refrained from providing sufficient coverage to the incident. A couple of weeks later, Devananda received appointment as the Prime Minister’s representative in the five-member Parliamentary Council, the successor to the former so called independent Constitutional Council, which in practice proved to be far from independent of the previous government. Minister Devananda’s statement hadn’t received the attention it deserved.

Wijewardena was kidnapped and killed in Jaffna, while he was travelling to Inuvil to investigate a shooting incident on August 4, 2005. The killing took place at Mallakam. Parliament also accommodated LTTE’s Eastern Commander, Karuna Amman, under whose command terrorists butchered over 400 unarmed surrendered policemen at the onset of the Eelam War II, in June 1990. Karuna served two terms as a lawmaker during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s tenure as the President. Karuna’s one-time junior associate LTTE cadre Pilleyan is now a Member of Parliament, whereas Karuna bid to enter Parliament, from Digamadulla, at the last general election, failed.

The JVP responsible for hundreds of deaths, if not thousands, too, is represented in Parliament – since 1994. The TNA that recognized the LTTE, in late 2001, as the sole representatives of the Tamil people, and then served them until the very end, is also represented in Parliament. The TNA includes three former terrorist groups, the TELO, PLOTE and EPRLF.

Sri Lanka’s politics is certainly an ‘explosive mix.’ Having failed to secure the presidency, Field Marshal Fonseka serves as a lawmaker. The war-winning Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa is the seventh executive President. Retired Rear Admiral Weerasekera is the Public Security Minister, whereas the LTTE and other Tamil groups, as well as the JVP, responsible for two bloody insurrections, are part of the system.

How Sajith Premadasa promoted Fonseka as his future Defence Minister, during the failed 2019 presidential campaign, and lawmaker and retired Supreme Court Justice C.W. Wigneswaran, exploiting the LTTE cause, as well as Gajendrakumar Ponnambalam’s fiery speeches in Parliament, are grim reminders the country is yet to achieve stability ten years after the war. Public Security Minister Weerasekera’s recent warning in Parliament that Tamil political parties promoted terrorism underscores the need to address security issue, regardless of political consequences.

Midweek Review

EPDP’s Devananda and missing weapon supplied by Army

After assassinating the foremost Sri Lankan Tamil political leader and one-time Opposition leader Appapillai Amirthalingam and ex-Jaffna MP Vettivelu Yogeswaran, in July 1989, in Colombo, the LTTE declared those who stepped out of line, thereby deviated from policy of separate state, would be killed. Ex-Nallur MP Murugesu Sivasithamparam was shot and wounded in the same incident. In 1994, the LTTE ordered the boycott of the general election but EPDP leader Douglas Devananda contested. His party won nine seats in the Jaffna peninsula.

The LTTE also banned the singing of the national anthem and the hoisting of the national flag at government and public functions in Tamil areas. Devananda defied this ban, too.

The Eelam People’s Democratic Party (EPDP) played a significant role in Sri Lanka’s overall campaign against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The EPDP threw its weight behind the war effort soon after the LTTE resumed hostilities in June 1990 after India withdrew forces deployed in terms of the Indo-Lanka Peace Accord signed on July 29, 1987, under duress, in the aftermath of the infamous uninvited ‘parippu drop’ over northern Sri Lanka by the Indian Air Force, a modern-day New Delhi version of the Western gunboat diplomacy.

India ended its military mission here in late March 1990. Having conducted an unprecedented destabilisation project against Sri Lanka, India ceased the mission with egg on her face. The monument erected near Sri Lanka Parliament for over 1,300 Indian military personnel, who made the supreme sacrifice here, is a grim reminder of the callous project.

In fact, the United National Party (UNP) government reached a consensus with the EPDP, PLOTE (People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam), ENDLF (Eelam National Democratic Liberation Front), TELO (Tamil Eelam Liberation Organisation) and EPRLF (Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front) for their deployment. Of them, the EPDP was among three groups ready to deploy cadres against the LTTE.

The LTTE ended its honeymoon (May 1989 to June 1990) with President Ranasinghe Premadasa. Within weeks after the resumption of hostilities, the government lost the Kandy-Jaffna A9 stretch of the road between north of Vavuniya and Elephant Pass.

It would be pertinent to mention that the above-mentioned groups suffered debilitating losses in the hands of the LTTE during the then Premadasa government’s honeymoon with the LTTE. At the behest of President Premadasa, the military provided tacit support for LTTE operations. But, in the wake of resumption of hostilities by the LTTE, the other groups grabbed the opportunity to reach consensus with the government, though they knew of President Premadasa’s treacherous actions.

On the invitation of the government, anti-LTTE Tamil groups set up ‘offices’ in Colombo. The writer first met Douglas Devananda at his ‘office’ at No. 22, Siripa Lane, Thimbirigasyaya, in November, 1990. There were scores of people. Some of them carried weapons. When Kathiravelu Nythiananda Devananda, wearing a sarong and short-sleeved banian, sat across a small table, facing the writer, he kept a pistol on the table. Devananda explained the role played by his group in Colombo and in the North-East region.

The so-called office had been used by the EPDP to question suspected LTTEers apprehended in Colombo. Those who are not familiar with the situation then may not be able to comprehend the complexity of overt and covert operations conducted by the military against Tiger terrorists. The EPDP, as well as other groups, namely the PLOTE and TELO, taking part in operations against the LTTE not only apprehended suspects but subjected them to strenuous interrogation. There had been excesses.

The UNP government provided funding for these groups, as well as weapons. In terms of the Indo-Lanka Accord signed on July 29, 1987, India and Sri Lanka agreed to disarm all groups, including the LTTE.

Following is the relevant section of the agreement: 2.9 The emergency will be lifted in the Eastern and Northern Provinces by Aug. 15, 1987. A cessation of hostilities will come into effect all over the island within 48 hours of signing of this agreement. All arms presently held by militant groups will be surrendered in accordance with an agreed procedure to authorities to be designated by the Government of Sri Lanka.

Consequent to the cessation of hostilities and the surrender of arms by militant groups, the Army and other security personnel will be confined to barracks in camps as on 25 May 1987. The process of surrendering arms and the confinement of security forces personnel moving back to barracks shall be completed within 72 hours of the cessation of hostilities coming into effect.

Formation of EPDP

An ex-colleague of Devananda, now living overseas, explained the circumstances of the one-time senior EPRLF cadre, EPDP leader switched his allegiance to the Sri Lankan government. Devananda formed the EPDP in the wake of a serious rift within the top EPRLF leadership. However, Devananda, at the time he had received training in Lebanon as a result of intervention made by UK based Tamils, served the Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students (EROS). Subsequently, a group that included K. Padmanabah formed the General Union of Students (GUES) before the formation of the EPRLF.

The formation of the EPDP should be examined taking into consideration Devananda’s alleged involvement in Diwali-eve murder in Chennai in 1986. Devananda’s ex-colleague claimed that his friend hadn’t been at the scene of the killing but arrived there soon thereafter.

Devananda, who had also received training in India in the ’80s, served as the first commander of the EPRLF’s military wing but never achieved a major success. However, the eruption of Eelam War II, in June, 1990, gave the EPDP an unexpected opportunity to reach an agreement with the government. In return for the deployment of the EPDP in support of the military, the government ensured that it got recognised as a registered political party. The government also recognised PLOTE, EPRLF and TELO as political parties. President Premedasa hadn’t been bothered about their past or them carrying weapons or accusations ranging from extrajudicial killings to extortions and abductions.

Some of those who found fault with President Premadasa for granting political recognition for those groups conveniently forgot his directive to then Election Commissioner, the late Chandrananda de Silva, to recognise the LTTE, in early Dec. 1989.

The writer was among several local and foreign journalists, invited by the late LTTE theoretician Anton Balasingham, to the Colombo Hilton, where he made the announcement. Chain-smoking British passport holder Balasingham declared proudly that their emblem would be a Tiger in a red flag of rectangular shape. Neither Premadasa, nor the late Chandrananda de Silva, had any qualms about the PFLT (political wing of the LTTE) receiving political recognition in spite of it being armed. The LTTE received political recognition a couple of months before Velupillai Prabhakaran resumed Eelam War II.

Devananda, in his capacity as the EPDP Leader, exploited the situation to his advantage. Having left Sri Lanka for India in May 1986, about a year before the signing of the Indo-Lanka Accord, Devananda returned to the country in May 1990, a couple of months after India ended its military mission here.

Of all ex-terrorists, Devananda achieved the impossible unlike most other ex-terrorist leaders. As the leader of the EPDP and him being quite conversant in English, he served as a Cabinet Minister under several Presidents and even visited India in spite of the Madras High Court declaring him as a proclaimed offender in the Chennai murder case that happened on Nov. 1, 1986. at Choolaimedu.

Regardless of his inability to win wider public support in the northern and eastern regions, Devananda had undermined the LTTE’s efforts to portray itself as the sole representative of the Tamil speaking people. In 2001, the LTTE forced the Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi (ITAK)-led Tamil National Alliance (TNA) to recognise Velupillai Prabhakaran as the sole representative of the Tamil speaking people.

Whatever various people say in the final analysis, Devananda served the interests of Sri Lanka like a true loyal son, thereby risked his life on numerous occasions until the military brought the war to a successful conclusion in May 2009. Devananda’s EPDP may have not participated in high intensity battles in the northern and eastern theatres but definitely served the overall military strategy.

During the conflict and after the EPDP maintained a significant presence in Jaffna islands, the US and like-minded countries resented the EPDP as they feared the party could bring the entire northern province under its domination by manipulating parliamentary, Provincial Council and Local Government elections. The West targeted the EPDP against the backdrop of the formation of the TNA under the late R. Sampanthan’s leadership to support the LTTE’s macabre cause, both in and outside Parliament. At the onset, the TNA comprised EPRLF, TELO, PLOTE and even TULF. But, TULF pulled out sooner rather than later. The EPDP emerged as the major beneficiary of the State as the LTTE, at gun point, brought all other groups under its control.

During the honeymoon between the government and the LTTE, the writer had the opportunity to meet Mahattaya along with a group of Colombo-based Indian journalists and veteran journalist, the late Rita Sebastian, at Koliyakulam, close to Omanthai, where LTTE’s No. 02 Gopalswamy Mahendrarajah, alias Mahattaya, vowed to finish off all rival Tamil groups. That meeting took place amidst a large-scale government backed campaign against rival groups, while India was in the process of de-inducting its troops (LTTE pledges to eliminate pro-Indian Tamil groups, The Island, January 10, 1990 edition).

Devananda survives two suicide attacks

The Ceasefire Agreement (CFA) worked out by Norway in 2002, too, had a clause similar to the one in the Indo-Lanka Accord of July 1987. While the 1987 agreement envisaged the disarming of all Tamil groups, the Norwegian one was meant to disarm all groups, other than the LTTE.

Devananda’s EPDP had been especially targeted as by then it remained the main Tamil group opposed to the LTTE, though it lacked wide public support due to the conservative nature of the Tamil society to fall in line with long established parties and their leaders. A section of the Tamil Diaspora that still couldn’t stomach the LTTE’s eradication were really happy about Devananda’s recent arrest over the recovery of a weapon issued to him by the Army two decades ago ending up with the underworld. The weapon, issued to Devananda, in 2001, was later recovered following the interrogation of organised criminal figure ‘Makandure Madush’ in 2019. Devananda has been remanded till January 9 pending further investigations.

Being the leader of a militant group forever hunted by Tiger terrorists surely he must have lost count of all the weapons he received on behalf of his party to defend themselves. Surely the Army has lost quite a number of weapons and similarly so has the police, but never has an Army Commander or an IGP remanded for such losses. Is it because Devananda stood up against the most ruthless terrorist outfit that he is now being hounded to please the West? Then what about the large quantities of weapons that Premadasa foolishly gifted to the LTTE? Was anyone held responsible for those treacherous acts?

Then what action has been taken against those who took part in the sinister Aragalaya at the behest of the West to topple a duly elected President and bring the country to its knees, as were similar putsch in Pakistan, Bangladesh effected to please white masters. Were human clones like the ‘Dolly the Sheep’ also developed to successfully carry out such devious plots?

Let me remind you of two suicide attacks the LTTE planned against Devananda in July 2004 and Nov. 2007. The first attempt had been made by a woman suicide cadre later identified as Thiyagaraja Jeyarani, who detonated the explosives strapped around her waist at the Kollupitiya Police station next to the Sri Lankan Prime Minister’s official residence in Colombo killing herself and four police personnel, while injuring nine others. The woman triggered the blast soon after the Ministerial Security Division (MSD) assigned to protect the then Hindu Cultural Affairs Minister Devananda handed her over to the Kollupitiya police station on suspicion. Investigations revealed that the suicide bomber had been a servant at the Thalawathugoda residence of the son of a former UNP Minister for about one and half years and was considered by the family as an honest worker (Bomber stayed with former UNP Minister’s son, The Island, July 12, 2004).

She had been planning to assassinate Devananda at his office situated opposite the Colombo Plaza. The police identified the person who provided employment to the assassin as a defeated UNP candidate who contested Kandy district at the April 2004 parliamentary election.

The second attempt on Devananda was made at his Ministry at Narahenpita on 28 Nov. 2007. Several hours later, on the same day, the LTTE triggered a powerful blast at Nugegoda, killing 10 persons and causing injuries to 40 others. The bomb had been wrapped in a parcel and was handed over to a clothing store security counter and detonated when a policeman carelessly handled the parcel after the shop management alerted police.

Having lost control of areas it controlled in the Eastern Province to the military by July 2007, the LTTE was battling two Army formations, namely 57 Division commanded by Brigadier Jagath Dias and Task Force 1 led by Colonel Shavendra Silva on the Vanni west front. The LTTE sought to cause chaos by striking Colombo. Obviously, the LTTE felt quite confident in eliminating Devananda, though the EPDP leader survived scores of previous assassination attempts. Devananda had been the Social Welfare Minister at the time. The Minister survived, but the blast triggered in his office complex killed one and inflicted injuries on two others.

Hardcore LTTE terrorists held at the Jawatte Jail, in Kalutara attacked Devananda on June 30, 1998, made an attempt on Devananda’s life when he intervened to end a hunger strike launched by a section of the prisoners. One of Devananda’s eyes suffered permanent impairment.

Devananda loses Jaffna seat

Having served as a Jaffna District MP for over three decades, Devananda failed to retain his seat at the last parliamentary election when the National People’s Power (NPP) swept all electoral districts. The NPP, in fact, delivered a knockout blow not only to the EPDP but ITAK that always enjoyed undisputed political power in the northern and eastern regions. Devananda, now in his late 60, under the present circumstances may find it difficult to re-enter Parliament at the next parliamentary elections, four years away.

Devananda first entered Parliament at the 1994 August general election. He has been re-elected to Parliament in all subsequent elections.

The EPDP contested the 1994 poll from an independent group, securing just 10,744 votes but ended up having nine seats. The polling was low due to most areas of the Jaffna peninsula being under LTTE control. But of the 10,744 votes, 9,944 votes came from the EPDP-controlled Jaffna islands. Devananda managed to secure 2,091 preference votes. That election brought an end to the 17-year-long UNP rule. By then Devananda’s first benefactor Ranasinghe Premadasa had been killed in a suicide attack and Devananda swiftly aligned his party with that of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s People’s Alliance (PA).

The LTTE mounted an attack on Devananda’s Colombo home on the night of Oct. 9, 1995. It had been one of 12 such attempts on his life

Devananda, who had survived the July 1983 Welikada Prison riot where Sinhala prisoners murdered 53 Tamils detainees. He then got transferred to Batticaloa Prison from where he escaped along with 40 others in September of the same year, received his first Cabinet position as Minister of Development, Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of the North, and Tamil Affairs, North and East following the 1994 general election. Devananda lost his Cabinet position following the PA’s defeat at the 2001 parliamentary election. Devananda entered the Cabinet as the Minister of Agriculture, Marketing Development, Hindu Education Affairs, Tamil Language & Vocational Training Centres in North following the UPFA’s victory at the 2004 general election.

Devananda further consolidated his position during Mahinda Rajapaksa’s presidency (2005 to 2015). He earned the wrath of the LTTE and Tamil Diaspora for his support for the government that eradicated the LTTE. Over the years, the EPDP’s role in overall security strategy diminished though the group maintained a presence in Jaffna islands.

There had been accusations against the EPDP. There had also been excesses on the part of the EPDP. But, Devananda and his men played an important role though not in numbers deployed against the LTTE. The EPDP proved that all Tamils didn’t follow the LTTE’s destructive path.

Three years after the eradication of the LTTE, in May 2009, President Mahinda Rajapaksa sent Devananda to the UN Human Rights Council as part of the official government delegation to Geneva.

Dr. Dayan Jayatilleka, Ambassador/ Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the United Nations Office in Geneva, comment on Devananda’s arrest is a must read. Devananda’s fate would have been different if he remained with the EPRLF, one of the Indian backed terrorist groups installed as the first North East Provincial Administration in which Jayatilleke served as Minister of Planning and Youth Affairs.

The EPRLF administration was brought to an unceremonious end when India ended its military mission here in 1990.

While multiple LTTE attempts to assassinate Devananda failed during the war with the last attempt made in late 2007, less than two years before the end of the conflict, obviously the EPDP leader remains a target. Those who still cannot stomach the LTTE’s humiliating defeat, seem to be jubilant over Devananda’s recent arrest over a missing weapon.

Therefore it is incumbent upon the NPP/JVP government to ensure the safety of Devananda under whatever circumstances as he has been a true patriot unlike many a bogus revolutionary in the present government from top to bottom, who are nothing more than cheap opportunists. Remember these same bogus zealots who threatened to sacrifice their lives to fight Indian threat to this country, no sooner they grabbed power became turncoats and ardent admirers of India overnight as if on a cue from Washington.

Various interested parties, including the US, relentlessly targeted the EPDP. US Embassy cable originating from Colombo quoted Stephen Sunthararaj, the then-Coordinator for the Child Protection Unit of World Vision in Jaffna directing a spate of allegations against the EPDP. In attempting to paint black the relationship between the military and the EPDP, Sunthararaj even accused the latter of child trafficking, sexual violence and running Tamil prostitution rings for soldiers.

The diplomatic cable also quoted the World Vision man as having said… because of the large number of widows in Jaffna, men associated with the EPDP, often from neighbouring villages, are used to seduce women with children, especially girls, with the promise of economic protection. After establishing a relationship, the men then take the children, sometimes by force and sometimes with the promise that they will be provided a better life.

The children are sold into slavery, usually boys to work camps and girls to prostitution rings, through EPDP’s networks in India and Malaysia.”

It would be interesting to examine whether World Vision at any time during the conflict took a stand against the use of child soldiers and indiscriminate use of women and children in high intensity battles and suicide missions by the LTTE. Did World Vision at least request the LTTE not to depend on human shields on the Vanni east front as the area under LTTE control gradually shrank? Have we ever heard of those who had been shedding crocodile tears for civilians opposing the LTTE’s despicable strategies? Never.

Against the backdrop of such accusations the non-inclusion of Devananda in some sanctioned list is surprising. Devananda, however, is receiving the treatment meted out to those Tamils who opposed the LTTE or switched allegiance to the government. Ex-LTTE Pilleyan and his one-time leader Karuna are among them. But unlike them, Devananda never served the LTTE’s despicable cause.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

Historical context of politicisation of Mahavamsa, and Tamil translation of the last volume

The sixth volume of the Mahavamsa, covering the period 1978-2010 has been rendered into Tamil by N. Saravanan, a well-known Tamil journalist and activist based in Norway. The first three volumes of the Mahavamsa (including the Culavamsa) are now a part of the UNESCO world heritage. They were the work of individual scholar monks, whereas the modern volumes (V to VI) were produced through state-sponsored collective efforts [1].

Although state-sponsored writing of history has been criticised, even the first Mahavamsa, presumably written by the Thera Mahanama in the 5th CE, probably enjoyed Royal Patronage. Furthermore, while it is not at all a sacred text, it is clearly a “Buddhist chronicle” compiled for the “serene joy of the pious” rather than a History of Ceylon, as compiled by, say the University of Ceylon. The latter project was a cooperative venture modeled after the Cambridge Histories. Unlike the Mahavamsa, which is a religious and poetic chronicle, the University effort was an academic work using critical historical methods and archaeological evidence. Hence the criticism [2] leveled against the Mahavamsa editorial board for lack of “inclusivity” (e.g., lack of Muslim or Hindu scholars in the editorial board) may be beside the point. The objection should only be that the ministry of culture has not so far sponsored histories written by other ethno-religious Lankan groups presenting their perspectives. In the present case the ministry of culture is continuing a unique cultural tradition of a Pali Epic, which is some nine centuries old. There has been no such continuous tradition of cultural historiography by other ethno-religious groups on this island (or elsewhere), for the cultural ministry to support.

Consequently, there is absolutely nothing wrong in stating (as Saravanan seems to say) that the Mahavamsa has been written by Buddhists, in the Pali language, “to promote a Sinhala-Buddhist historical perspective”. There IS no such thing as unbiased history. Other viewpoints are natural and necessary in history writing, and they too should be sponsored and published if there is sufficient interest.

While this is the first translation of any of the volumes of the Mahavamsa into Tamil, there were official translations of the Mahavamsa (by Ven. Siri Sumangala and others) into Sinhalese even during British rule, commissioned by the colonial government to make the text accessible to the local people. Although the Legislative Council of the country at that time was dominated by Tamil legislators (advisors to the Governor), they showed no interest in a Tamil translation.

The disinterest of the Tamil community regarding the Mahavamsa changed dramatically after the constitutional reforms of the Donoughmore commission (1931). These reforms gave universal franchise to every adult, irrespective of ethnicity, caste, creed or gender. The Tamil legislators suddenly found that the dominant position that they enjoyed within the colonial government would change dramatically, with the Sinhalese having a majority of about 75%, while the “Ceylon Tamils” were no more than about 12%. The Tamil community, led by caste conscious orthodox members became a minority stake holder with equality granted to those they would not even come face to face, for fear of “caste pollution”.

There was a sudden need for the Tamils to establish their “ownership” of the nation vis-a-vis the Sinhalese, who had the Pali chronicles establishing their historic place in the Island. While the Mahawamsa does not present the Sinhalese as the original settlers of the Island, colonial writers like Baldeus, de Queroz, Cleghorn, Emerson Tennant, promoted the narrative that the Sinhalese were the “original inhabitants” of the Island, while Tamils were subsequent settlers who arrived mostly as invaders. This has been the dominant narrative among subsequent writers (e.g., S. G. Perera, G. C. Mendis), until it was challenged in the 1940s with the rise of Tamil nationalism. Modern historians such as Kartihesu Indrapala, or K. M. de Silva consider that Tamil-speaking people have been present in Sri Lanka since prehistoric or proto-historic times, likely arriving around the same time as the ancestors of the Sinhalese (approx. 5th century BCE). Given that Mannar was a great seaport in ancient times, all sorts of people from the Indian subcontinent and even the Levant must have settled in the Island since pre-historic times.

Although Dravidian people have lived on the land since the earliest times, they have no Epic chronicle like the Mahavamsa. The Oxford & Peradeniya Historian Dr. Jane Russell states [3] that Tamils “had no written document on the lines of the Mahavamsa to authenticate their singular and separate historical authority in Sri Lanka, a fact which Ceylon Tamil communalists found very irksome”. This lack prompted Tamil writers and politicians, such as G. G. Ponnambalam, to attack the Mahavamsa or to seek to establish their own historical narratives. Using such narratives and considerations based on wealth, social standing, etc., a 50-50 sharing of legislative power instead of universal franchise was proposed by G. G. Ponnambalam (GGP), including only about 5% of the population in the franchise, in anticipation of the Soulbury commission. Meanwhile, some Tamil writers tried to usurp the Mahavamsa story by suggesting that King Vijaya was Vijayan, and King Kashyapa was Kasi-appan, etc., while Parakramabahu was “two-thirds” Dravidian. These Tamil nationalists failed to understand that the Mahavamsa authors did not care that its kings were “Sinhalese” or “Tamil”, as long as they were Buddhists! Saravanan makes the same mistake by claiming that Vijaya’s queen from Madura was a Tamil and suggesting a “race-based” reason for Vijaya’s action. This would have had no significance to the Mahavamsa writer especially as Buddhism had not yet officially arrived in Lanka! However, it may well be that Vijaya was looking for a fair-skinned queen from the nearest source, and Vijaya knew that south Indian kings usually had fair-skinned (non-Dravidian) North Indian princesses as their consorts. In fact, even today Tamil bride grooms advertising in matrimonial columns of newspapers express a preference for fair-complexioned brides.

The 1939 Sinhala-Tamil race riot was triggered by a speech where GGP attacked the Mahavamsa and claimed that the Sinhalese were really a “mongrel race”. It was put down firmly within 24 hours by the British Raj. Meanwhile, E. L. Tambimuttu published in 1945 a book entitled Dravida: A History of the Tamils, from Pre-historic Times to A.D. 1800. It was intended to provide a historical narrative for the Tamils, to implicitly rival the Sinhalese chronicle, the Mahavamsa. SJV Chelvanayakam was deeply impressed by Tambimuttu’s work and saw in it the manifesto of a nationalist political party that would defeat Ponambalam’s Tamil congress. So, the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kadchi, seeking a high degree of self rule for Tamils in their “exclusive traditional homelands”, saw the light of day in 1949, in the wake of Ceylon’s independence from the British.

G. G. Ponnambalam and SWRD Bandaranaike were the stridently ethno-nationalist leaders of the Tamils and Sinhalese respectively, until about 1956. After the passage of the “Sinhala only” act of SWRD, Chelvanayagam took the leadership of Tamil politics. The ensuing two decades generated immense distrust and communal clashes between Sinhalese and Tamils parties, with the latter passing the Vaddukoddai resolution (1976) that called for even taking up arms to establish an Independent Tamil state – Eelam– in the “exclusive” homelands of the Tamils. It is a historical irony that Vaddukkodai was known as “Batakotta” until almost 1900 and indicated a “garrison fort” used by Sinhalese kings to station soldiers (bhata) to prevent local chiefs from setting up local lordships with the help of south Indian kings.

The last volume of the Mahavamsa that has been translated into Tamil by N. Saravanan, covers the contentious period (1978-2010) following the Vaddukkodai resolution and the Eelam wars. This is the period regarding which a militant Tamil writer would hold strong dissenting views from militant Sinhalese. The tenor of Saravanan’s own writings emphasises what he calls the “genocidal nature” of “Sinhala-Buddhist politics” via vis the Tamils. He asserts that the Sri Lankan state used this “Mahavamsa-based ideology” to justify the Eelam War and subsequent actions he characterises as genocidal, including the alleged “Sinhalisation” of Tamil heritage sites.

We should remember that the Eelam wars spanned three decades, while many attempts to resolve the conflict via “peace talks” failed. A major sticking point was the LTTE’s position that even if it would not lay down arms. Saravanan may have forgotten that the Vaddukkodai resolution, though a political declaration, used the language of a “sacred fight” and its demand for absolute separation provided the political framework for the ensuing civil war. So, if the justification for the Eelam wars is to be found in the Mahavamsa, no mention of it was made at Vaddukkoddai. Instead, the “sacred fight” concept goes back to the sacrificial traditions of Hinduism. The concept of a “sacred” or “righteous” fight in Hinduism is known as Dharma-yuddha. While featured and justified in the Mahabharata and Ramayana, its foundational rules and legal frameworks are codified across several other ancient Indian texts. The Bhagavad Gita provides the spiritual justification for Arjuna’s participation in the Kurukshetra War, framing it as a “righteous war” where fighting is a moral obligation. The Arthashastra is a treatise that categorises warfare, distinguishing Dharmayuddha from Kutayuddha (war using deception) and Gudayuddha (covert warfare). While acknowledging Dharmayuddha as the ideal, it pragmatically advocates deception when facing an “unrighteous” enemy.

Saravanan claims that “the most controversial portion is found in the first volume of the Mahavamsa“. He highlights specific passages, such as the Dutugemunu-Elara episode, where monks allegedly tell the king that “killing thousands of Tamils” was permissible because they were “no better than beasts”. This statement is untrue as the monks did not mention Tamils.

What did the monks say to console the king? The king had said: ‘How can there be peace for me, venerable ones, when countless lives have been destroyed by my hand?’ The Theras replied: ‘By this act, there is no obstacle to your path to heaven, O ruler of men. In truth, you have slain only one and a half human beings. One of them sought refuge in the Three Jewels, and the other took the Five Precepts. The rest were unbelievers, evil men who are not to be valued higher than beasts.

This discourse does not even single out or target “Tamils”, contrary to Saravanan’s claim. It mentions unbelievers. The text is from the 5th Century CE. As a person well versed in the literature of the subcontinent, Saravanan should know how that in traditional Hindu scripture killing a Brahmin or a holy person is classified as one of the most heinous sins, ranked higher than the killing of an ordinary layman or killing a person holding onto miccātiṭṭi – (misbelief). The ranking of the severity of such sins is given in texts like the Manusmriti and Chandogya Upanishad, and align with the concepts in the Hindu Manu Dharma that dictate how “low caste” people have been treated in Jaffna society from time immemorial. Hence it is indeed surprising that Sravanan finds the discourse of the monks as something unusual and likely to be the cause of an alleged genocide of the Tamils some 16 centuries later. It was a very mild discourse for that age and in the context of Hindu religious traditions of the “sacred fight” invoked at Vaddukoddai.

Furthermore, Sarvanan should be familiar with the Mahabharat, and the justification given by Krishna for killing his opponents. In the Mahabharata, Krishna justifies the killing of his opponents by prioritising the restoration of Dharma (righteousness) over rigid adherence to conventional rules of war or personal relationships. This was exactly the sentiment contained in the statement of the monks, that “Oh king, you have greatly advanced the cause of the Buddha’s doctrine. Therefore, cast away your sorrow and be comforted.’

So, are we to conclude that Sarvanan is unaware of the cultural traditions of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism and the ranking of sins that exist in them, and is he now using the Human Rights concepts of modern times in trying to damn the Mahavamsa? Does he really believe that the majority of the 15 million Sinhala Buddhists have read the Mahavamsa and are activated to kill “unbelievers”? Does he not know that most of these Buddhists also frequent Hindu shrines and hardly regard Hindus beliefs as Mithyadristi? How is it that the majority of Tamils reside in Sinhalese areas peacefully if the Sinhalese are still frenzied by the words of the monks given to console King Dutugamunu 16 centuries ago?

Instead of looking at the ranking of sins found in Indian religions during the time Mahanama wrote the Mahavamsa, let us look at how unbelievers were treated in the Abrahamic religions during those times, and even into recent times. As unbelievers, infidels and even unbaptised men and women of proper faith were deemed to certainly go to hell, and killing infidels was no sin. Historical massacres were justified as divine mandates for the protection of the faith. The Hebrew Bible contains instances where God commanded the Israelites to “utterly destroy all (unbelievers) that breathed”. Medieval Christian and Islamic authorities viewed non-believers or heretics as a spiritual “infection.” Prelates like Augustine of Hippo argued for the state’s use of force to “correct” heretics or eliminate them. Some theologians argued that God being the creator of life, His command to end a life (specially of an “infidel”) is not “murder”.

In contrast, in the Mahavamsa account the king killed his enemies in battle, and the monks consoled him using the ranking of sins recognised in the Vedic, Jain and Buddhist traditions.

If looked at in proper perspective, Sarvanan’s translation of the last volume of at least the Mahavamsa is a valuable literary achievement. But his use of parts of the 5th century Mahavamsa that is not even available to the Tamil reader is nothing but hate writing. He or others who think like him should first translate the old Mahavamsa and allow Tamil-speaking people to make their own judgments about whether it is a work that would trigger genocide 16 centuries later or recognise that there is nothing in the Mahavamsa that is not taken for granted in religions of the Indian subcontinent.

References:

[1]https://www.culturaldept.gov.lk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=36&Itemid=178&lang=en#:~:text=The%20Mahavamsa%20(%22Great%20Chronicle%22%20is%20the%20meticulously,epic%20poem%20written%20in%20the%20Pali%20language.

[2] https://www.jaffnamonitor.com/the-roots-of-sri-lankas-genocidal-mindset-and-anti-indian-sentiment-lie-in-the-mahavamsa-writer-n-saravanan-on-his-bold-new-translation/#:~:text=Share%20this%20post,have%20been%20silenced%20or%20overlooked.

[3] Jane Russell, Communal Politics in Ceylon under the Donoughmore Constitution, 1931-1948. Ceylon Historical Journal, vol. 36, and Tisara Publishers, Dehiwala, Sri Lanka (1982).

by Chandre Dharmawardana

chandre.dharma@yahoo.ca

Midweek Review

Historic Citadel Facing Threat

The all-embracing august citadel,

Which blazed forth a new world order,

Promising to protect the earth’s peoples,

But built on the embers of big power rivalry,

Is all too soon showing signs of crumbling,

A cruel victim, it’s clear, of its own creators,

And the hour is now to save it from falling,

Lest the world revisits a brink of the forties kind.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoBroad support emerges for Faiszer’s sweeping proposals on long- delayed divorce and personal law reforms

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoInterception of SL fishing craft by Seychelles: Trawler owners demand international investigation

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoPharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoUS raid on Venezuela violation of UN Charter and intl. law: Govt.

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoEducational reforms under the NPP government