Features

Politics and Administrators in the 20th Century

The Kandy Man – An Autobiography, Volume one (1939-1977),

By Sarath Amunugam. Vijitha Yapa Publications (2020).548 pages

Reviewed by Leelananda De Silva

Introduction

In two years, Sri Lanka should celebrate 75 years since independence. During this period, there have been dramatic social, cultural and economic changes. The British inheritance is fading fast, whether it be in Government and administration, politics and constitution making, in education and in foreign relations. It is time for the university academics or some others to consider writing the history of Sri Lanka these last 75 years and capture the momentous changes that have occurred. Whether that history will be written in Sinhalese, Tamil or English is yet to be seen. Sarath Amunugama’s volume is an important building block in constructing that history.

Amunugama is one of the outstanding personalities of Sri Lanka in our generation. An academic, top administrator and leading politician, he has played an important role in Sri Lankan public life. He has lived in and served the country in an era of rapid change. Amunugama is one of the very few members of the Ceylon Civil Service to have moved into high level politics after 1948. The others were C. Suntheralingam, C. Sittampalam, Walwin. A. de Silva, Ronnie de Mel and Nissanka Wijeyaratne. The volume under review is only the first part of a three-volume autobiography. Broadly, the current volume addresses three broad areas – his education at Trinity College, Kandy in the 1940s and at the University of Ceylon at Peradeniya in the 1950s; as a high level district administrator in the 1960s; and at the centre of Government as Director of Information in the 1970s. He has straddled the demarcations between administration and politics with ease and he has worked with politicians of all hues comfortably.

Trinity College, Kandy

The first chapter of this volume deals with his school days at Trinity College, Kandy. He offers us a wide ranging picture of Trinity and also of Kandy of that time. He describes College academic life, sports and cadeting and student debates with other schools, especially the girls’ schools in Kandy. Regrettably, there is no reference to the subjects they debated about. Amunugama has great admiration for some of his teachers. Hillary Abeyaratne was one of his heroes, and others were R.R. Breckenridge, Willy Hensman and Gordon Burrows. He greatly admired his Principal, Norman Walter, probably one of the last school principals of British origin in Sri Lanka. Walter wrote to the Vice Chancellor of the University requesting that Amunugama be admitted to the University although he was underage, a request that could not be granted.

Our generation, whether it be from schools in Colombo or Galle, knew of Trinity largely because of a famous Principal, A.G. Fraser and a British teacher and preacher, Rev. W.S. Senior, who wrote some delightful, haunting poetry about Kandy. Amunugama’s story of Trinity could have been better if he dealt with the history of Trinity and the influence the College had on the Kandyan middle and upper classes. Trinity was a great inheritance from British days.

The University at Peradeniya

In the 1950s, the University at Peradeniya (part of the University of Ceylon) was unique in the history of universities in Sri Lanka. It had only about a thousand students, and the faculties were almost entirely of the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences. There was no Physical Science, Engineering or Medicine. This lasted for only a decade. The undergraduates lived in halls of residence not far from each other. All this tended to make the university a friendly and even homely place, with friendships across disciplines and residencies.

In the 1950s, the University at Peradeniya (part of the University of Ceylon) was unique in the history of universities in Sri Lanka. It had only about a thousand students, and the faculties were almost entirely of the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences. There was no Physical Science, Engineering or Medicine. This lasted for only a decade. The undergraduates lived in halls of residence not far from each other. All this tended to make the university a friendly and even homely place, with friendships across disciplines and residencies.

Amunugama seems to have enjoyed the university in his four years there and was fully engaged in its academic, political and cultural life. He was active in various groups, especially with E.R. Sarachchandra and Siri Gunasinghe. This was the time of Maname, a Sarachchandra play which revolutionized Sri Lankan drama and with which Amunugama was closely associated. He offers us an excellent picture of the cultural activities of the university at that time. This was also a time when undergraduates studied in the English medium and yet Sinhala culture was flourishing.

He offers us a fascinating picture of the Sociology department at the university in its early days. S.J. Thambiah and Gananath Obeysekara were students and lecturers. Later on, they were to become world class academics, teaching at Princeton and Harvard in the U.S.A. Laksiri Jayasuriya and Ralph Pieris were other leading academics. There are engaging pen portraits of these academics. Amunugama appears to be an admirer of Ralph Pieris, who was his teacher. He tells us the story of Jennings’s hesitation in setting up departments of Sinhala culture and sociology as these subjects were strange to the Oxbridge traditions from which Jennings had emerged. He also tells us of the differences that Martin Wickramasinghe had with Jennings’ approach to Sinhala cultural studies and also of the pioneering role played by Professor Ratnasuriya who died young. The volume also offers us some insight into university politics but there is no space to get into detail here. However it must be noted that Amunugama was President of the Union Society at Peradeniya during his time there. Overall, the volume offers an engaging picture of the University at Peradeniya of the 1950s.

District Administration

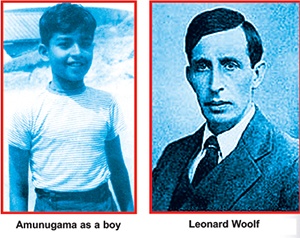

Since Amunugama entered the Ceylon Civil Service in 1963 (the CCS was abolished soon after), the next seven years of his career was in district administration. He served as AGA and Additional GA in Galle, Ratnapura and Kandy districts. Amunugama’s academic background was ideal to deal with the range of issues that he had to face in the districts. His 200-page story of his engagement in district administration reminds me of Leonard Woolf’s volume “Growing 1904 – 1911” (the second volume of his five volume autobiography, published in the 1960s), which is about his seven years in Ceylon and when he was engaged in district administration. Unlike in imperial days, the district administrator in the 1960s had to deal with politicians and a democratic government. They were no longer the rulers like Leonard Woolf.

The young Civil Servant’s interests were so expansive that he was in a position to fruitfully interact in the area of agriculture and lands and irrigation, culture, the arts and the temples and with the politics of these districts. In the Galle district, where he served for nearly three years, he established a good relationship with the legendary W. Dahanayake, MP for Galle and his Minister of Home Affairs in later years. Amunugama was immersed in the cultural life of the Galle district and he had a friendly relationship with the DROs of the area. When in Galle, he became very familiar with the backgrounds of two of the great cultural figures of our time – Martin Wickramasinghe and Gunadasa Amarasekara, visiting many of the villages and the scenes depicted in their novels.

In the Kandy district, Amunugama was again very involved in the political and cultural life of the district. He initiated the concept of mobile kacheries which enabled the villagers, instead of coming to Kandy, to have their problems addressed near their own villages. He also initiated a more effective approach to increase the productive capacity of farmers. Local village level officials who should assist the farmers were not living in the villages they were officially attached to, but were commuting to their own homes. Amunugama started the practice of giving these field officers lands of their own, so that they will live with the farmers and work with them. He has many stories to relate about his relationships with the politicians of the day like Anuruddha Ratwatte in Kandy. In the Ratnapura district, he was deeply engaged in land development in the Udawalawe and Chandrika weva colonization schemes.

Overall, the chapters entitled “The Ceylon Civil Service” and “Government Agent”, are in effect addressing issues in district administration. It’s a matter of some curiosity why he titled these two chapters in this way instead of making them chapters on district administration. By the time he was AGA and Additional GA and serving in the districts, the CCS had been abolished. The CCS lasted only the first year of his public service career. Since that time, he and other ex-CCS officers were members of the Ceylon Administrative Service (CAS).

I understand the hesitations of some of the ex-CCS personnel to use the new CAS nomenclature. However, difficult it is for them, to call themselves CCS after its abolition in 1963, is like Grama Sevakas calling themselves village headmen and DROs calling themselves Mudliyars. These were denominations of an imperial era. Amunugama tells us that when their batch joined the CCS, on their first day, the then Secretary to the Treasury and Head of the CCS, Shirley Amarasinghe addressed them on how to behave. Interestingly, within one year of that day, Shirley Amarasinghe (who was only 50 years old at the time) himself left the CCS and joined the Ceylon Overseas Service to go as High Commissioner to India.

Director of Information

Amunugama moved into the centre of Government when he was appointed Director of Information in 1968 when Dudley Senanayake was Prime Minister. He continued his tenure under Mrs. Sirima Bandaranaike when she became Prime Minister in 1970. This is an assignment which suited Amunugama’s academic, administrative and political skills. His story of these years is compulsive reading and there are entertaining stories of politics at the highest level. At a young age, he was able to interact with the top politicians of his day. During this period, he also engaged in what looks to be his pastime – international travel – which he has done extensively over the years. In fact, the volume has many paragraphs and stories of his foreign travels including a long spell in Canada reading for a postgraduate degree.

As Director of Information, he was privy to much of the politics of his time. There are fascinating stories of the tensions between the LSSP and the SLFP when they were in coalition in the 1970s. There are engaging portraits of R. Premadasa when he was Minister of Local Government. Who could have known that Premadasa, when he was Deputy Minister of Local Government, had a very high regard for his Minister M. Tiruchelvam at the time when the UNP had formed a coalition with the Federal Party.

The writer relates the story of how the State Film Corporation was shifted from his ministry to the Ministry of Planning and Economic Affairs, where I had to handle its affairs. There are many other vignettes of his time as Director of Information of top politicians like Dudley Senanayake, Mrs. Bandaranaike, N.M. Perera and many others.

Conclusion

To conclude my review, let me refer to the long Preface of this book which addresses questions of writing biographies and autobiographies. Many biographies in Sri Lanka of leading politicians are largely hagiographies, praising them no end. This was the pattern of autobiographical writing too. In the early 1920s, there was a dramatic change in the art of biographical writing. Lytton Strachey, a member of the Bloomsbury group (a close friend of Leonard and Virginia Woolf) wrote his “Eminent Victorians” which changed the art of biography. Of his chosen few biographical topics, which included Queen Victoria and Florence Nightingale, he wrote about these leading icons of that generation, warts and all, bringing them down a peg or two.

This introduced a new form of biography, which was more investigative, critical and more true to the lives of their subjects. Autobiographies can never be swallowed whole. To paraphrase Robert Burns, the great Scottish poet, no power has given us the gift “to see ourselves as others see us.” That is the inherent weakness of autobiography. Amunugama’s first volume of a three volume autobiography is an outstanding work in its field, and is a great addition to our knowledge of our contemporary times. It was a pleasure to read.

Features

Inescapable need to deal with the past

by Jehan Perera

The sudden reemergence of two major incidents from the past, that had become peripheral to the concerns of people today, has jolted the national polity and come to its centre stage. These are the interview by former president Ranil Wickremesinghe with the Al Jazeera television station that elicited the Batalanda issue and now the sanctioning of three former military commanders of the Sri Lankan armed forces and an LTTE commander, who switched sides and joined the government. The key lesson that these two incidents give is that allegations of mass crimes, whether they arise nationally or internationally, have to be dealt with at some time or the other. If they are not, they continue to fester beneath the surface until they rise again in a most unexpected way and when they may be more difficult to deal with.

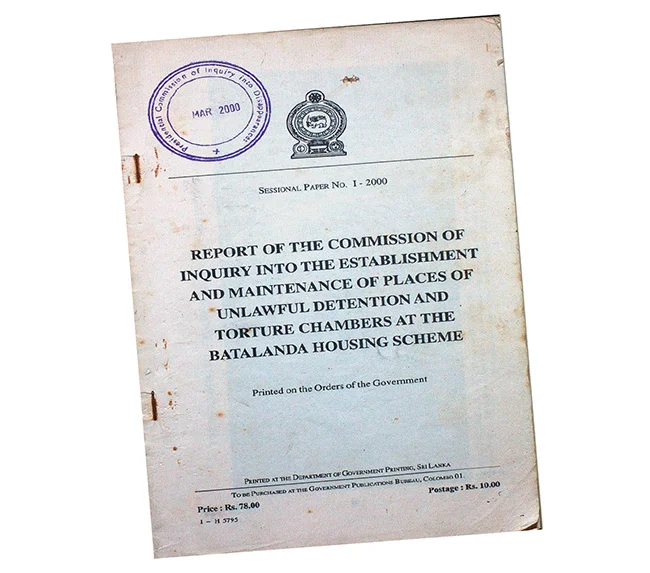

In the case of the Batalanda interrogation site, the sudden reemergence of issues that seemed buried in the past has given rise to conjecture. The Batalanda issue, which goes back 37 years, was never totally off the radar. But after the last of the commission reports of the JVP period had been published over two decades ago, this matter was no longer at the forefront of public consciousness. Most of those in the younger generations who were too young to know what happened at that time, or born afterwards, would scarcely have any idea of what happened at Batalanda. But once the issue of human rights violations surfaced on Al Jazeera television they have come to occupy centre stage. From the day the former president gave his fateful interview there are commentaries on it both in the mainstream media and on social media.

There seems to be a sustained effort to keep the issue alive. The issues of Batalanda provide good fodder to politicians who are campaigning for election at the forthcoming Local Government elections on May 6. It is notable that the publicity on what transpired at Batalanda provides a way in which the outcome of the forthcoming local government elections in the worst affected parts of the country may be swayed. The problem is that the main contesting political parties are liable to be accused of participation in the JVP insurrection or its suppression or both. This may account for the widening of the scope of the allegations to include other sites such as Matale.

POLITICAL IMPERATIVES

The emergence at this time of the human rights violations and war crimes that took place during the LTTE war have their own political reasons, though these are external. The pursuit of truth and accountability must be universal and free from political motivations. Justice cannot be applied selectively. While human rights violations and war crimes call for universal standards that are applicable to all including those being committed at this time in Gaza and Ukraine, political imperatives influence what is surfaced. The sanctioning of the four military commanders by the UK government has been justified by the UK government minister concerned as being the fulfilment of an election pledge that he had made to his constituents. It is notable that the countries at the forefront of justice for Sri Lanka have large Tamil Diasporas that act as vote banks. It usually takes long time to prosecute human rights violations internationally whether it be in South America or East Timor and diasporas have the staying power and resources to keep going on.

In its response to the sanctions placed on the military commanders, the government’s position is that such unilateral decisions by foreign government are not helpful and complicate the task of national reconciliation. It has faced criticism for its restrained response, with some expecting a more forceful rebuttal against the international community. However, the NPP government is not the first to have had to face such problems. The sanctioning of military commanders and even of former presidents has taken place during the periods of previous governments. One of the former commanders who has been sanctioned by the UK government at this time was also sanctioned by the US government in 2020. This was followed by the Canadian government which sanctioned two former presidents in 2023. Neither of the two governments in power at that time took visibly stronger stands.

In addition, resolutions on Sri Lanka have been a regular occurrence and have been passed over the Sri Lankan government’s opposition since 2012. Apart from the very first vote that took place in 2009 when the government promised to take necessary action to deal with the human rights violations of the past, and won that vote, the government has lost every succeeding vote with the margins of defeat becoming bigger and bigger. This process has now culminated in an evidence gathering unit being set up in Geneva to collect evidence of human rights violations in Sri Lanka that is on offer to international governments to use. This is not a safe situation for Sri Lankan leaders to be in as they can be taken before international courts in foreign countries. It is important for Sri Lanka’s sovereignty and dignity as a country that this trend comes to an end.

COMPREHENSIVE SOLUTION

A peaceful future for Sri Lanka requires a multi-dimensional approach that addresses the root causes of conflict while fostering reconciliation, justice, and inclusive development. So far the government’s response to the international pressures is to indicate that it will strengthen the internal mechanisms already in place like the Office on Missing Persons and in addition to set up a truth and reconciliation commission. The difficulty that the government will face is to obtain a national consensus behind this truth and reconciliation commission. Tamil parties and victims’ groups in particular have voiced scepticism about the value of this mechanism. They have seen commissions come and commissions go. Sinhalese nationalist parties are also highly critical of the need for such commissions. As the Nawaz Commission appointed to identify the recommendations of previous commissions observed, “Our island nation has had a surfeit of commissions. Many witnesses who testified before this commission narrated their disappointment of going before previous commissions and achieving nothing in return.”

Former minister Prof G L Peiris has written a detailed critique of the proposed truth and reconciliation law that the previous government prepared but did not present to parliament.

In his critique, Prof Peiris had drawn from the South African truth and reconciliation commission which is the best known and most thoroughly implemented one in the world. He points out that the South African commission had a mandate to cover the entire country and not only some parts of it like the Sri Lankan law proposes. The need for a Sri Lankan truth and reconciliation commission to cover the entire country and not only the north and east is clear in the reemergence of the Batalanda issue. Serious human rights violations have occurred in all parts of the country, and to those from all ethnic and religious communities, and not only in the north and east.

Dealing with the past can only be successful in the context of a “system change” in which there is mutual agreement about the future. The longer this is delayed, the more scepticism will grow among victims and the broader public about the government’s commitment to a solution. The important feature of the South African commission was that it was part of a larger political process aimed to build national consensus through a long and strenuous process of consultations. The ultimate goal of the South African reconciliation process was a comprehensive political settlement that included power-sharing between racial groups and accountability measures that facilitated healing for all sides. If Sri Lanka is to achieve genuine reconciliation, it is necessary to learn from these experiences and take decisive steps to address past injustices in a manner that fosters lasting national unity. A peaceful Sri Lanka is possible if the government, opposition and people commit to truth, justice and inclusivity.

Features

Unleashing Minds: From oppression to liberation

By Anushka Kahandagamage

Education should be genuinely ‘free’—not just in the sense of being free from privatisation, but also in a way that empowers students by freeing them from oppressive structures. It should provide them with the knowledge and tools necessary to think critically, question the status quo, and ultimately liberate themselves from oppressive systems.

Education should be genuinely ‘free’—not just in the sense of being free from privatisation, but also in a way that empowers students by freeing them from oppressive structures. It should provide them with the knowledge and tools necessary to think critically, question the status quo, and ultimately liberate themselves from oppressive systems.

Education as an oppressive structure

Education should empower students to think critically, challenge oppression, and envision a more just and equal world. However, in its current state, education often operates as a mechanism of oppression rather than liberation. Instead of fostering independent thinking and change, the education system tends to reinforce the existing power dynamics and social hierarchies. It often upholds the status quo by teaching conformity and compliance rather than critical inquiry and transformation. This results in the reproduction of various inequalities, including economic, racial, and social disparities, further entrenching divisions within society. As a result, instead of being a force for personal and societal empowerment, education inadvertently perpetuates the very systems that contribute to injustice and inequality.

Education sustaining the class structure

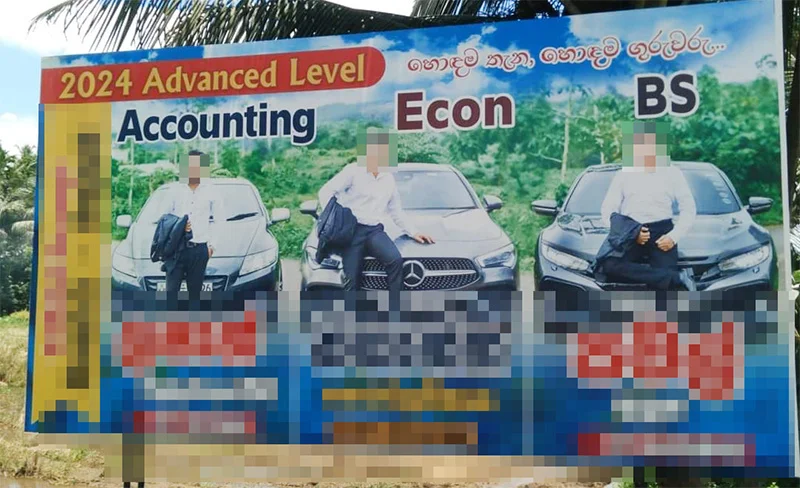

Due to the widespread privatisation of education, the system continues to reinforce and sustain existing class structures. Private tuition centres, private schools, and institutions offering degree programmes for a fee all play a significant role in deepening the disparities between different social classes. These private entities often cater to the more affluent segments of society, granting them access to superior education and resources. In contrast, students from less privileged backgrounds are left with fewer opportunities and limited access to quality education, exacerbating the divide between the wealthy and the underprivileged. This growing gap in educational access not only limits social mobility but also perpetuates a cycle where the privileged continue to secure better opportunities while the less fortunate struggle to break free from the constraints of their socio-economic status.

Gender Oppression

Education subtly perpetuates gender oppression in society by reinforcing stereotypes, promoting gender insensitivity, and failing to create a gender-sensitive education system. And some of the policymakers do perpetuate this gender insensitive education by misinforming people. In a recent press conference, one of the former members of Parliament, Wimal Weerawansa, accused gender studies of spreading a ‘disease’ among students. In the year 2025, we are still hearing such absurdities discouraging gender studies. It is troubling and perplexing to hear such outdated and regressive views being voiced by public figures, particularly at a time when societies, worldwide, are increasingly embracing diversity and inclusion. These comments not only undermine the importance of gender studies as an academic field but also reinforce harmful stereotypes that marginalise individuals who do not fit into traditional gender roles. As we move forward in an era of greater social progress, such antiquated views only serve to hinder the ongoing work of fostering equality and understanding for all people, regardless of gender identity.

Students, whether in schools or universities, are often immersed in an educational discourse where gender is treated as something external, rather than an essential aspect of their everyday lives. In this framework, gender is framed as a concern primarily for “non-males,” which marginalises the broader societal impact of gender issues. This perspective fails to recognise that gender dynamics affect everyone, regardless of their gender identity, and that understanding and addressing gender inequality is crucial for all individuals in society.

A poignant example of this issue can be seen in the recent troubling case of sexual abuse involving a medical doctor. The public discussion surrounding the incident, particularly the media’s decision to disclose the victim’s confidential statement, is deeply concerning. This lack of respect for privacy and sensitivity highlights the pervasive disregard for gender issues in society.

What makes this situation even more alarming is that such media behaviour is not an isolated incident, but rather reflects a broader pattern in a society where gender sensitivity is often dismissed or ignored. In many circles, advocating for gender equality and sensitivity is stigmatised, and is even seen as a ‘disease’ or a disruptive force to the status quo. This attitude contributes to a culture where harmful gender stereotypes persist, and where important conversations about gender equity are sidelined or distorted. Ultimately, this reflects the deeper societal need for an education system that is more attuned to gender sensitivity, recognising its critical role in shaping the world students will inherit and navigate.

To break free from these gender hierarchies there should be, among other things, a gender sensitive education system, which does not limit gender studies to a semester or a mere subject.

Ragging

The inequality that persists in class and regional power structures (Colombo and non-Colombo division) creeps into universities. While ragging is popularly seen as an act of integrating freshers into the system, its roots lie in the deeply divided class and ethno-religious divisions within society.

In certain faculties, senior students may ask junior female students to wear certain fabrics typically worn at home (cheetta dresses) and braid their hair into two plaits, while male students are required to wear white, long-sleeved shirts without belts. Both men and women must wear bathroom slippers. These actions are framed as efforts to make everyone equal, free from class divisions. However, these gendered and ethicised practices stem from unequal and oppressive class structures in society and are gradually infiltrating university culture as mechanisms of oppression.The inequality that persists in gradually makes its way into academic institutions, particularly universities.

These practices are ostensibly intended to create a sense of uniformity and equality among students, removing visible markers of class distinction. However, what is overlooked is that these actions stem from deeply ingrained and unequal social structures that are inherently oppressive. Instead of fostering equality, they reinforce a system where hierarchical power dynamics in the society—rooted in class, gender, and region—are confronted with oppression and violence which is embedded in ragging, creating another system of oppression.

Uncritical Students

In Sri Lanka, and in many other countries across the region, it is common for university students to address their lecturers as ‘Sir’ and ‘Madam.’ This practice is not just a matter of politeness, but rather a reflection of deeply ingrained societal norms that date back to the feudal and colonial eras. The use of these titles reinforces a hierarchical structure within the educational system, where authority is unquestioned, and students are expected to show deference to their professors.

Historically, during colonial rule, the education system was structured around European models, which often emphasised rigid social distinctions and the authority of those in power. The titles ‘Sir’ and ‘Madam’ served to uphold this structure, positioning lecturers as figures of authority who were to be respected and rarely challenged. Even after the end of colonial rule, these practices continued to permeate the education system, becoming normalised as part of the culture.

This practice perpetuates a culture of obedience and respect for authority that discourages critical thinking and active questioning. In this context, students are conditioned to see their lecturers as figures of unquestionable authority, discouraging dialogue, dissent, or challenging the status quo. This hierarchical dynamic can limit intellectual growth and discourage students from engaging in open, critical discussions that could lead to progressive change within both academia and society at large.

Unleashing minds

The transformation of these structures lies in the hands of multiple parties, including academics, students, society, and policymakers. Policymakers must create and enforce policies that discourage the privatisation of education, ensure equal access for all students, regardless of class dynamics, gender, etc. Education should be regarded as a fundamental right, not a privilege available only to a select few. Such policies should also actively promote gender equality and inclusivity, addressing the barriers that prevent women, LGBTQ+ individuals, and other marginalised genders from accessing and succeeding in education. Practices that perpetuate gender inequality, such as sexism, discrimination, or gender-based violence, need to be addressed head-on. Institutions must prioritise gender studies and sensitivity training to cultivate an environment of respect and understanding, where all students, regardless of gender, feel safe and valued.

At the same time, the micro-ecosystems of hierarchy within institutions—such as maintaining outdated power structures and social divisions—must be thoroughly examined and challenged. Universities must foster environments where critical thinking, mutual respect, and inclusivity—across both class and gender—are prioritised. By creating spaces where all minds can flourish, free from the constraints of entrenched hierarchies, we can build a more equitable and intellectually vibrant educational system—one that truly unleashes the potential of all students, regardless of their social background.

(Anushka Kahandagamage is the General Secretary of the Colombo Institute for Human Sciences)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

Features

New vision for bassist Benjy

It’s a known fact that whenever bassist Benjy Ranabahu booms into action he literally lights up the stage, and the exciting news I have for music lovers, this week, is that Benjy is coming up with a new vision.

One thought that this exciting bassist may give the music scene a layoff, after his return from the Seychelles early this year.

At that point in time, he indicated to us that he hasn’t quit the music scene, but that he would like to take a break from the showbiz setup.

“I’m taking things easy at the moment…just need to relax and then decide what my future plans would be,” he said.

However, the good news is that Benjy’s future plans would materialise sooner than one thought.

Yes, Benjy is putting together his own band, with a vision to give music lovers something different, something dynamic.

He has already got the lineup to do the needful, he says, and the guys are now working on their repertoire.

The five-piece lineup will include lead, rhythm, bass, keyboards and drums and the plus factor, said Benjy, is that they all sing.

A female vocalist has also been added to this setup, said Benjy.

“She is relatively new to the scene, but with a trained voice, and that means we have something new to offer music lovers.”

The setup met last week and had a frank discussion on how they intend taking on the music scene and everyone seems excited to get on stage and do the needful, Benjy added.

Benjy went on to say that they are now spending their time rehearsing as they are very keen to gel as a team, because their skills and personalities fit together well.

“The guys I’ve got are all extremely talented and skillful in their profession and they have been around for quite a while, performing as professionals, both here and abroad.”

Benjy himself has performed with several top bands in the past and also had his own band – Aquarius.

Aquarius had quite a few foreign contracts, as well, performing in Europe and in the Middle East, and Benjy is now ready to do it again!

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoCelebrating 25 Years of Excellence: The Silver Jubilee of SLIIT – PART I

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCEB calls for proposals to develop two 50MW wind farm facilities in Mullikulam

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAIA Higher Education Scholarships Programme celebrating 30-year journey

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoNotes from AKD’s Textbook

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSanctions by The Unpunished