Features

POLICE PROMOTION MANIPULATION: VIOLATION OF THE LINE OF SENIORITY

Root cause of the decline of the force

(Excerpted from Merril Gunaratne’s ‘Perils of a Profession’ )

In a disciplined service, rank is sacrosanct. An officer has necessarily to aspire to higher rank through performance. If his work had been of exceptional merit and distinction, he may even be considered for a special promotion. A promotion can also be posthumous where the deceased officer had been exemplary in performance and achievement. An officer will therefore naturally like to safeguard his position in the line of seniority. He will be unhappy if a junior officer is placed over him merely because the latter wields influence. It is natural for an officer in a disciplined service to jealously protect his place in the line of seniority against encroachment.

Two matters of concern had emerged in the wake of the exacerbation of ‘interference’ that had plagued the police since 1977. Those who looked for undue favours from the police by baiting officers with assurances of recognition and promotion outside the line of seniority, had often found pliant policemen ready to do their bidding. Many have thus prospered without satisfying the required criteria for key posts and promotions. The pattern, so monotonous since 1977, had seriously demoralized the service. Some have been adept not only in the ” long jump,” but also in “hop, step, and jump”, by the acquisition of more than one rank promotion outside the ” eligibility criteria”.

The second matter for concern had been the ineptitude of IGPs to counter this pattern. The fundamental premise in leadership is the undiluted authority of the leader to reward the good and punish the errant. This foundation was uprooted in 1977 mostly because those at the helm of affairs in the police abdicated or surrendered to political demands without resistance to interference. If a united front was presented based on a cohesive policy, the political establishment may have found it formidable.

The inadequacies of those in the highest echelons to stand up and protest at the onset, enabled the entrenchment of a pernicious system. The good were often overlooked, whilst some of those with chequered careers but were favourites of patrons, found recognition. The IGP became a figurehead who watched passively. Attempts to resist such pressure and insist on the right course would have been costly. Cyril Herath alone stood up to such a demand and quit his position of IGP, rejecting a compensatory sop of a diplomatic assignment. Such honorable conduct was a noble alternative to taking the easy road, a lesson to the establishment, and an inspiration to the service.

A few instances of the violation of the line of security.

Following the sweeping victory of Chandrika Kumaratunga as the president in 1994, six police officers, after being away from the force for some time, were reinstated in the service in the rank of senior DIG. They were thereby restored to positions they enjoyed in the seniority line at the time they left the service. Of these six officers, Messrs Rajaguru, Wickramasuriya and Iddamalgoda were victims of persecution as extensions of service was denied them without valid reasons. The others did not fall into such a category, with two of them quitting on their own, while the third had been served notice of vacation of post. Those who were dislodged from their positions in the seniority line by such reinstatement had served without interruption in the most taxing and testing times. Somewhere in 2018 or 2019, three DIGs who had retired long time ago, decided to appeal for promotion to senior DIG rank. The ‘Yahapalanaya’ government promoted them through a political victimization committee. This was incredible.

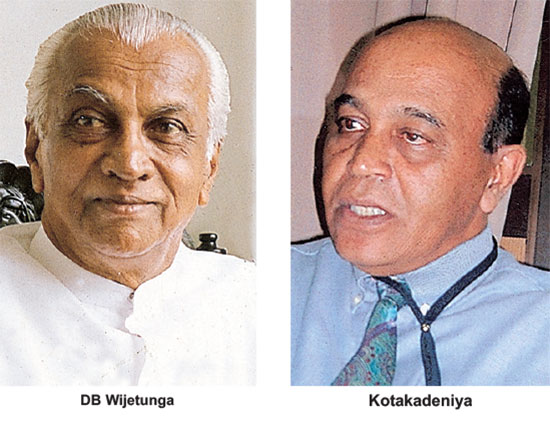

Inflation of the DIG cadre when D B Wijetunga was president.

Shortly after DB Wijetunga became president, the government suddenly took a decision to introduce a radical increase in the DIG cadre. The directive came from the president, and his proposals should have been examined in depth, before being implemented. The DIG cadre increased from 19 to 30 overnight. An SSP was able to secure a DIG rank from the ninth or 10th place in the line of seniority when the number of DIGs was raised to 11. The coincidence of the enlargement of the DIG cadre and the simultaneous accommodation of this officer close to the president at the tail end of the expanded number of 11 DIGs gave rise to considerable speculation. I had dealt with this controversy in my book “Cop in the Crossfire”.

In fact if a cohesive policy with fixed quotas based on cogent reasoning was firmly in place, there may have been space and scope to explain why such a sudden increase in the DIG cadre would have been difficult to accommodate. Anyway, the president’s suggestion required a careful study to assess whether it was possible to accede to the request. I was then third or fourth in line of seniority from the IGP down but my views were not solicited. I think a study in regard to the request of the president should have included “inter alia”, the following: Did the service face additional responsibilities to warrant an expansion? Above all, did numbers in subordinate ranks – SSPs, SPs, ASPs, inspectorate, sergeants and constables, justify a sudden increase in the DIG cadre? Would the radical increase have disturbed ratios, proportions and balance? In actual fact, even if we assume that the request was to increase the cadre by one or two more, a rational decision had to depend on a proper study.

President Wijetunga was generous in interfering with, or fragmenting police ranges to placate officers. Two weeks before my promotion to the rank of senior DIG, T.V. Sumanasekara was appointed as DIG of Mt Lavinia and Kalutara divisions which actually were within my range. I promptly telephoned the president and requested him to carve out the new range after my promotion, so that I would not be embarrassed. The president agreed, and as a result, the dismemberment of my range was suspended till my promotion. Such was the level of interference at that time.

Even the cadre of senior DIGs which stood at three when president Wijetunga assumed duties, rose to five in the same manner as the increase in the cadre of DIGs. A DIG secured a promotion to the rank of SDIG shortly before retirement. The officer concerned was in a post which had, before such promotion and even after, been assigned only to a DIG. Therefore this promotion was secured despite there being no vacancies in the cadre. The cadre of senior DIGs then became five since the officer lying ahead of the officer who thus secured a promotion, rushed to the president and argued that he would lose his position in the line of seniority unless he was also promoted. The largesse of president Wijetunga bestowing promotions disregarding standards, rules and procedures of a service knew no limits.

POSTSCRIPT (this is not part of the book)

Responding to a perceptive review of the book, “Perils of a Profession” by Shamindra Ferdinando in the daily “Island” paper, veteran retired Senior DIG HMGB Kotakadeniya had pointed out in the issue of Jan. 20, 2021 that when DB Wijetunga was president, the DIG cadre was increased from 19 to over 40, and not 30, as stated in my book. He had also pointed out that such an increase in the cadre was possibly done to elevate Senior Superintendent of Police Mahinda Balasuriya who was lying 44th in the line of seniority, to the rank of DIG.

Never in the history of the police had the cadre of DIGs been increased in such a manner. This political decision was shocking. It also shed light on how a self seeking officer can abuse and bend standards at will and acquire benefits when two factors are in place: first, when enjoying a post close to the head of state/government; second, when the head of the service fails to preserve the required balance between the interests of the service and those of officers.

The usual tactic of those who aspire to steal others’ places in the line of seniority and become DIG is to overtake a few officers through the influence of patrons. Balasuriya could not adopt this ruse because he was very junior, being 44th in the line of seniority, with 25 SSPs/SPs ahead of him. Climbing over such large numbers would have earned the ire of a large number of officers facing displacement. He therefore appears to have used his position to persuade the president to enlarge the DIG cadre from 19 to 44 to reach him.

But before doing so in such a sweeping manner, President Wijetunga had first invited the views of Senior DIG Kotakadeniya whom he knew, and who was serving in a key position in police headquarters, whether DIGs could be posted to police ranges as “Welfare” DIGs. SDIG Kotakadeniya had said in all sincerity that such an arrangement would have been superfluous and therefore absurd. Had he agreed to the proposal, the president may have justified the inflation on the score that the service required a large number of DIGs to supervise welfare arrangements.

Having failed in this subtle bid, the order for the enlargement of the DIG cadre far out of proportion to necessity to accommodate Balasuriya appears to have been brazenly imposed on the police service by President Wijetunga. The most reasonable inference that could be drawn was that there was not only clear collusion between the President and Balasuriya, but that Snr DIG Kotakadeniya had apparently been victimized by being shifted out of his key post for his dissent. An honest, professional opinion had resulted in persecution. Frank de Silva was IGP when the massive inflation of the DIG cadre occurred, resulting in Balasuriya being the beneficiary. I am thankful to the retired Senior DIG for providing the backdrop to the subtle plan. They was truly “scenes behind the scenes”.

The organisation of any institution, particularly the police, has to resemble a pyramidal structure. It has to be narrow at the top, as the IGP and his deputies (DIGs) would be numerically few, being vested with the task of coordinating large bodies of men and large areas or territory than SPs and ASPs relatively junior in rank. The higher the rank, the role of coordination of work would entail far greater territory and oversight. The responsibility to determine numbers in senior ranks rests with the IGP and his deputies, and should be underscored by specific criteria and standards. As a result of what Balasuriya unjustly acquired, the cadre of DIGs enlarged to a point disproportionate to the strength of the numbers in ranks below them.

Consequently, many DIGs’ had to perform “coordination functions” of SSPs and SPs overlooking police divisions. To have called such a unit in the range of a DIG would have been a misnomer. The excess committed by Balasuriya was analogous to a bottle where the mouth was wider in diameter than the girth at it’s center. Such a distorted shape cannot be ideal to hold water or anything else. As a result of there being far too many DIGs than necessary, vacancies for promotion were also galore, and some SSPs reached DIG rank and DIGs, Senior DIG rank, without being adequately tried and tested in their previous ranks. Could this be one reason why the IGP, senior DIGS and DIGs had failed to react with responsibility and maturity in the face of intelligence received from India about plans by the NTJ to commit terror strikes on Easter Sunday in 2019? Many of those who acquired benefits also displayed greater loyalties to their patrons rather than to the service.

The sudden expansion in the DIG and Senior DIG cadre between 1989 and 1995 out of proportion to necessity may have been one of the major contributory factors toward the gradual decline of police standards. In fact the staggering increase of DIGs on a political diktat, saw implementation without even a discussion in police headquarters with officers in the highest echelons. The cornerstones or fundamental prerequisites which help any institution to prosper are first the organization’s vision, concepts and goals; second, the identification of the ideal administrative structure to run it and third, the posting of competent persons to the senior slots in the structure.

Once the structure loses shape, and corresponding postings lose meaning or purpose, the “out of shape” organization becomes far less effective. If the excess or surfeit of DIGs had an adverse impact on performance, the remedy would obviously have been a drastic reduction in the DIG cadre. But this was not possible because once promoted, an officer cannot be reduced or demoted, unless for disciplinary reasons. The harm caused to the service had therefore been irreversible. Knowing the capricious nature of humans, an institution such as the police should hold the balance between self seeking officers one the one hand, and the interests and well being of the service on the other. The interests of the service should always predominate or prevail over devious designs of self-seekers.

This balance has to be maintained by the IGP. His abdication of this responsibility would allow self-seekers to abuse standards at will. The submission and surrender by police heads to demands from the politicl establishment for arbitrary cadre increases and backdoor promotions contrasted sharply with what prevails int he the armed services. Their chiefs always held the policy in regard to senior cadre and promotions as their exclusive preserve.

The undesirable process had it’s roots in the days of IGP Ernest Perera in 1987 when the Ministry of Defence commenced holding interviews among senior superintendents to select DIGs. It was a move to wrest the authority previously enjoyed by the IGP to nominate SSPs to fill the vacancies in the DIG Cadre. Submission without a murmur to this arrangement paved the way for greater encroachment.

Features

Challenges faced by the media in South Asia in fostering regionalism

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

That South Asian governments have had a hand in the ‘SAARC debacle’ is plain to see. For example, it is beyond doubt that the India-Pakistan rivalry has invariably got in the way, particularly over the past 15 years or thereabouts, of the Indian and Pakistani governments sitting at the negotiating table and in a spirit of reconciliation resolving the vexatious issues growing out of the SAARC exercise. The inaction had a paralyzing effect on the organization.

Unfortunately the rest of South Asian governments too have not seen it to be in the collective interest of the region to explore ways of jump-starting the SAARC process and sustaining it. That is, a lack of statesmanship on the part of the SAARC Eight is clearly in evidence. Narrow national interests have been allowed to hijack and derail the cooperative process that ought to be at the heart of the SAARC initiative.

However, a dimension that has hitherto gone comparatively unaddressed is the largely negative role sections of the media in the SAARC region could play in debilitating regional cooperation and amity. We had some thought-provoking ‘takes’ on this question recently from Roman Gautam, the editor of ‘Himal Southasian’.

Gautam was delivering the third of talks on February 2nd in the RCSS Strategic Dialogue Series under the aegis of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, Colombo, at the latter’s conference hall. The forum was ably presided over by RCSS Executive Director and Ambassador (Retd.) Ravinatha Aryasinha who, among other things, ensured lively participation on the part of the attendees at the Q&A which followed the main presentation. The talk was titled, ‘Where does the media stand in connecting (or dividing) Southasia?’.

Gautam singled out those sections of the Indian media that are tamely subservient to Indian governments, including those that are professedly independent, for the glaring lack of, among other things, regionalism or collective amity within South Asia. These sections of the media, it was pointed out, pander easily to the narratives framed by the Indian centre on developments in the region and fall easy prey, as it were, to the nationalist forces that are supportive of the latter. Consequently, divisive forces within the region receive a boost which is hugely detrimental to regional cooperation.

Two cases in point, Gautam pointed out, were the recent political upheavals in Nepal and Bangladesh. In each of these cases stray opinions favorable to India voiced by a few participants in the relevant protests were clung on to by sections of the Indian media covering these trouble spots. In the case of Nepal, to consider one example, a young protester’s single comment to the effect that Nepal too needed a firm leader like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was seized upon by the Indian media and fed to audiences at home in a sensational, exaggerated fashion. No effort was made by the Indian media to canvass more opinions on this matter or to extensively research the issue.

In the case of Bangladesh, widely held rumours that the Hindus in the country were being hunted and killed, pogrom fashion, and that the crisis was all about this was propagated by the relevant sections of the Indian media. This was a clear pandering to religious extremist sentiment in India. Once again, essentially hearsay stories were given prominence with hardly any effort at understanding what the crisis was really all about. There is no doubt that anti-Muslim sentiment in India would have been further fueled.

Gautam was of the view that, in the main, it is fear of victimization of the relevant sections of the media by the Indian centre and anxiety over financial reprisals and like punitive measures by the latter that prompted the media to frame their narratives in these terms. It is important to keep in mind these ‘structures’ within which the Indian media works, we were told. The issue in other words, is a question of the media completely subjugating themselves to the ruling powers.

Basically, the need for financial survival on the part of the Indian media, it was pointed out, prompted it to subscribe to the prejudices and partialities of the Indian centre. A failure to abide by the official line could spell financial ruin for the media.

A principal question that occurred to this columnist was whether the ‘Indian media’ referred to by Gautam referred to the totality of the Indian media or whether he had in mind some divisive, chauvinistic and narrow-based elements within it. If the latter is the case it would not be fair to generalize one’s comments to cover the entirety of the Indian media. Nevertheless, it is a matter for further research.

However, an overall point made by the speaker that as a result of the above referred to negative media practices South Asian regionalism has suffered badly needs to be taken. Certainly, as matters stand currently, there is a very real information gap about South Asian realities among South Asian publics and harmful media practices account considerably for such ignorance which gets in the way of South Asian cooperation and amity.

Moreover, divisive, chauvinistic media are widespread and active in South Asia. Sri Lanka has a fair share of this species of media and the latter are not doing the country any good, leave alone the region. All in all, the democratic spirit has gone well into decline all over the region.

The above is a huge problem that needs to be managed reflectively by democratic rulers and their allied publics in South Asia and the region’s more enlightened media could play a constructive role in taking up this challenge. The latter need to take the initiative to come together and deliberate on the questions at hand. To succeed in such efforts they do not need the backing of governments. What is of paramount importance is the vision and grit to go the extra mile.

Features

When the Wetland spoke after dusk

By Ifham Nizam

As the sun softened over Colombo and the city’s familiar noise began to loosen its grip, the Beddagana Wetland Park prepared for its quieter hour — the hour when wetlands speak in their own language.

World Wetlands Day was marked a little early this year, but time felt irrelevant at Beddagana. Nature lovers, students, scientists and seekers gathered not for a ceremony, but for listening. Partnering with Park authorities, Dilmah Conservation opened the wetland as a living classroom, inviting more than a 100 participants to step gently into an ecosystem that survives — and protects — a capital city.

Wetlands, it became clear, are not places of stillness. They are places of conversation.

Beyond the surface

In daylight, Beddagana appears serene — open water stitched with reeds, dragonflies hovering above green mirrors.

Yet beneath the surface lies an intricate architecture of life. Wetlands are not defined by water alone, but by relationships: fungi breaking down matter, insects pollinating and feeding, amphibians calling across seasons, birds nesting and mammals moving quietly between shadows.

Participants learned this not through lectures alone, but through touch, sound and careful observation. Simple water testing kits revealed the chemistry of urban survival. Camera traps hinted at lives lived mostly unseen.

Demonstrations of mist netting and cage trapping unfolded with care, revealing how science approaches nature not as an intruder, but as a listener.

Again and again, the lesson returned: nothing here exists in isolation.

Learning to listen

Perhaps the most profound discovery of the day was sound.

Wetlands speak constantly, but human ears are rarely tuned to their frequency. Researchers guided participants through the wetland’s soundscape — teaching them to recognise the rhythms of frogs, the punctuation of insects, the layered calls of birds settling for night.

Then came the inaudible made audible. Bat detectors translated ultrasonic echolocation into sound, turning invisible flight into pulses and clicks. Faces lit up with surprise. The air, once assumed empty, was suddenly full.

It was a moment of humility — proof that much of nature’s story unfolds beyond human perception.

Sethil on camera trapping

The city’s quiet protectors

Environmental researcher Narmadha Dangampola offered an image that lingered long after her words ended. Wetlands, she said, are like kidneys.

“They filter, cleanse and regulate,” she explained. “They protect the body of the city.”

Her analogy felt especially fitting at Beddagana, where concrete edges meet wild water.

She shared a rare confirmation: the Collared Scops Owl, unseen here for eight years, has returned — a fragile signal that when habitats are protected, life remembers the way back.

Small lives, large meanings

Professor Shaminda Fernando turned attention to creatures rarely celebrated. Small mammals — shy, fast, easily overlooked — are among the wetland’s most honest messengers.

Using Sherman traps, he demonstrated how scientists read these animals for clues: changes in numbers, movements, health.

In fragmented urban landscapes, small mammals speak early, he said. They warn before silence arrives.

Their presence, he reminded participants, is not incidental. It is evidence of balance.

Narmadha on water testing pH level

Wings in the dark

As twilight thickened, Dr. Tharaka Kusuminda introduced mist netting — fine, almost invisible nets used in bat research.

He spoke firmly about ethics and care, reminding all present that knowledge must never come at the cost of harm.

Bats, he said, are guardians of the night: pollinators, seed dispersers, controllers of insects. Misunderstood, often feared, yet indispensable.

“Handle them wrongly,” he cautioned, “and we lose more than data. We lose trust — between science and life.”

The missing voice

One of the evening’s quiet revelations came from Sanoj Wijayasekara, who spoke not of what is known, but of what is absent.

In other parts of the region — in India and beyond — researchers have recorded female frogs calling during reproduction. In Sri Lanka, no such call has yet been documented.

The silence, he suggested, may not be biological. It may be human.

“Perhaps we have not listened long enough,” he reflected.

The wetland, suddenly, felt like an unfinished manuscript — its pages alive with sound, waiting for patience rather than haste.

The overlooked brilliance of moths

Night drew moths into the light, and with them, a lesson from Nuwan Chathuranga. Moths, he said, are underestimated archivists of environmental change. Their diversity reveals air quality, plant health, climate shifts.

As wings brushed the darkness, it became clear that beauty often arrives quietly, without invitation.

Sanoj on female frogs

Coexisting with the wild

Ashan Thudugala spoke of coexistence — a word often used, rarely practiced. Living alongside wildlife, he said, begins with understanding, not fear.

From there, Sethil Muhandiram widened the lens, speaking of Sri Lanka’s apex predator. Leopards, identified by their unique rosette patterns, are studied not to dominate, but to understand.

Science, he showed, is an act of respect.

Even in a wetland without leopards, the message held: knowledge is how coexistence survives.

When night takes over

Then came the walk: As the city dimmed, Beddagana brightened. Fireflies stitched light into darkness. Frogs called across water. Fish moved beneath reflections. Insects swarmed gently, insistently. Camera traps blinked. Acoustic monitors listened patiently.

Those walking felt it — the sense that the wetland was no longer being observed, but revealed.

For many, it was the first time nature did not feel distant.

Faunal diversity at the Beddagana Wetland Park

A global distinction, a local duty

Beddagana stands at the heart of a larger truth. Because of this wetland and the wider network around it, Colombo is the first capital city in the world recognised as a Ramsar Wetland City.

It is an honour that carries obligation. Urban wetlands are fragile. They disappear quietly. Their loss is often noticed only when floods arrive, water turns toxic, or silence settles where sound once lived.

Commitment in action

For Dilmah Conservation, this night was not symbolic.

Speaking on behalf of the organisation, Rishan Sampath said conservation must move beyond intention into experience.

“People protect what they understand,” he said. “And they understand what they experience.”

The Beddagana initiative, he noted, is part of a larger effort to place science, education and community at the centre of conservation.

Listening forward

As participants left — students from Colombo, Moratuwa and Sabaragamuwa universities, school environmental groups, citizens newly attentive — the wetland remained.

It filtered water. It cooled air. It held life.

World Wetlands Day passed quietly. But at Beddagana, something remained louder than celebration — a reminder that in the heart of the city, nature is still speaking.

The question is no longer whether wetlands matter.

It is whether we are finally listening.

Features

Cuteefly … for your Valentine

Valentine’s Day is all about spreading love and appreciation, and it is a mega scene on 14th February.

Valentine’s Day is all about spreading love and appreciation, and it is a mega scene on 14th February.

People usually shower their loved ones with gifts, flowers (especially roses), and sweet treats.

Couples often plan romantic dinners or getaways, while singles might treat themselves to self-care or hang out with friends.

It’s a day to express feelings, share love, and make memories, and that’s exactly what Indunil Kaushalya Dissanayaka, of Cuteefly fame, is working on.

She has come up with a novel way of making that special someone extra special on Valentine’s Day.

Indunil is known for her scented and beautifully turned out candles, under the brand name Cuteefly, and we highlighted her creativeness in The Island of 27th November, 2025.

She is now working enthusiastically on her Valentine’s Day candles and has already come up with various designs.

“What I’ve turned out I’m certain will give lots of happiness to the receiver,” said Indunil, with confidence.

In addition to her own designs, she says she can make beautiful candles, the way the customer wants it done and according to their budget, as well.

Customers can also add anything they want to the existing candles, created by Indunil, and make them into gift packs.

Customers can also add anything they want to the existing candles, created by Indunil, and make them into gift packs.

Another special feature of Cuteefly is that you can get them to deliver the gifts … and surprise that special someone on Valentine’s Day.

Indunil was originally doing the usual 9 to 5 job but found it kind of boring, and then decided to venture into a scene that caught her interest, and brought out her hidden talent … candle making

And her scented candles, under the brand ‘Cuteefly,’ are already scorching hot, not only locally, but abroad, as well, in countries like Canada, Dubai, Sweden and Japan.

“I give top priority to customer satisfaction and so I do my creative work with great care, without any shortcomings, to ensure that my customers have nothing to complain about.”

“I give top priority to customer satisfaction and so I do my creative work with great care, without any shortcomings, to ensure that my customers have nothing to complain about.”

Indunil creates candles for any occasion – weddings, get-togethers, for mental concentration, to calm the mind, home decorations, as gifts, for various religious ceremonies, etc.

In addition to her candle business, Indunil is also a singer, teacher, fashion designer, and councellor but due to the heavy workload, connected with her candle business, she says she can hardly find any time to devote to her other talents.

Indunil could be contacted on 077 8506066, Facebook page – Cuteefly, Tiktok– Cuteefly_tik, and Instagram – Cuteeflyofficial.

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoGovt. provoking TUs

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition