Features

Oscars 2025: The list of winners from the 97th Academy Awards

Anora, a screwball comedy-drama about a sex worker who marries a Russian oligarch’s son, walked away with the biggest prizes at the 97th annual Academy Awards. The film won the awards for Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Director, Best Editing and Best Original Screenplay.

The musical Emilia Perez, which had the highest total nominations with 13 nods, scooped up wins for Best Original Song and Best Supporting Actress on Sunday night.

Adrien Brody won Best Actor for The Brutalist – his second Oscar. In 2003, Brody became the youngest person to win the Best Actor award for The Pianist at the age of 29. Mikey Madison won Best Actress for Anora.

Kieran Culkin bagged the Best Supporting Actor award for A Real Pain, and Paul Tazewell became the first Black man to win the award for Best Costume Design for Wicked.

No Other Land nabbed Best Documentary Feature for its stark portrayal of Israeli settler violence against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank.

Best picture

- Anora – Winner

- The Brutalist

- A Complete Unknown

- Conclave

- Dune: Part Two

- Emilia Perez

- I’m Still Here

- Nickel Boys

- The Substance

- Wicked

Best Actor

- Adrien Brody, for The Brutalist – Winner

- Timothee Chalamet, for A Complete Unknown

- Colman Domingo, for Sing Sing

- Ralph Fiennes, for Conclave

- Sebastian Stan, for The Apprentice

Best Actress

- Mikey Madison, for Anora – Winner

- Cynthia Erivo, for Wicked

- Karla Sofia Gascon, for Emilia Perez

- Demi Moore, for The Substance

- Fernanda Torres, for I’m Still Here

Best Supporting Actress

- Zoe Saldana for Emilia Perez – Winner

- Ariana Grande, for Wicked

- Monica Barbaro, for A Complete Unknown

- Felicity Jones, for The Brutalist

- Isabella Rossellini, for Conclave

Best Supporting Actor

- Kieran Culkin for A Real Pain – Winner

- Yura Borisov, for Anora

- Edward Norton, for A Complete Unknown

- Guy Pearce, for The Brutalist

- Jeremy Strong, for The Apprentice

International Feature Film

- I’m Still Here – Winner

- The Girl with the Needle

- Emilia Perez

- The Seed of the Sacred Fig

- Flow

Documentary Feature

- No Other Land – Winner

- Black Box Diaries

- Porcelain War

- Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat

- Sugarcane

Original Song

- El Mal from Emilia Perez – Winner

- Never Too Late from Elton John: Never Too Late

- Mi Camino from Emilia Perez

- Like A Bird from Sing Sing

- The Journey from The Six Triple Eight

Original Screenplay

- Sean Baker for Anora – Winner

- Brady Corbet and Mona Fastvold for The Brutalist

- Jesse Eisenberg for A Real Pain

- Moritz Binder, Tim Fehlbaum, Alex David for September 5

- Coralie Fargeat for The Substance

Adapted Screenplay

- Peter Straughan for Conclave – Winner

- Jay Cocks and James Mangold for A Complete Unknown

- Jacques Audiard for Emilia Perez

- RaMell Ross and Joslyn Barnes for Nickel Boys

- Clint Bentley and Greg Kwedar for Sing Sing

Animated Feature Film

- Flow – Winner

- Inside Out 2

- Memoir of a Snail

- Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl

- The Wild Robot

Visual Effects

- Dune: Part Two – Winner

- Alien: Romulus

- Better Man

- Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

- Wicked

Costume Design

- Paul Tazewell for Wicked – Winner

- Linda Muir for Nosferatu

- Arianne Phillips for A Complete Unknown

- Lisy Christl for Conclave

- Janty Yates and Dave Crossman for Gladiator II

Cinematography

- The Brutalist – Winner

- Dune: Part Two

- Emilia Perez

- Maria

- Nosferatu

Documentary Short Film

- The Only Girl in the Orchestra – Winner

- Death by Numbers

- I Am Ready, Warden

- Incident

- Instruments of a Beating Heart

Best Sound

- Dune: Part Two – Winner

- A Complete Unknown

- Emilia Perez

- Wicked

- The Wild Robot

Production Design

- Wicked – Winner

- The Brutalist

- Dune: Part Two

- Nosferatu

- Conclave

Makeup and Hairstyling

- The Substance – Winner

- A Different Man

- Emilia Perez

- Nosferatu

- Wicked

Film Editing

- Sean Baker for Anora – Winner

- David Jancso for The Brutalist

- Nick Emerson for Conclave

- Juliette Welfling for Emilia Perez

- Myron Kerstein for Wicked

Live Action Short Film

- I’m Not a Robot – Winner

- Anuja

- The Last Ranger

- A Lien

- The Man Who Could Not Remain Silent

Animated Short Film

- In the Shadow of the Cypress – Winner

- Beautiful Men

- Magic Candies

- Wander to Wonder

- Yuck!

[Aljazeera]

Features

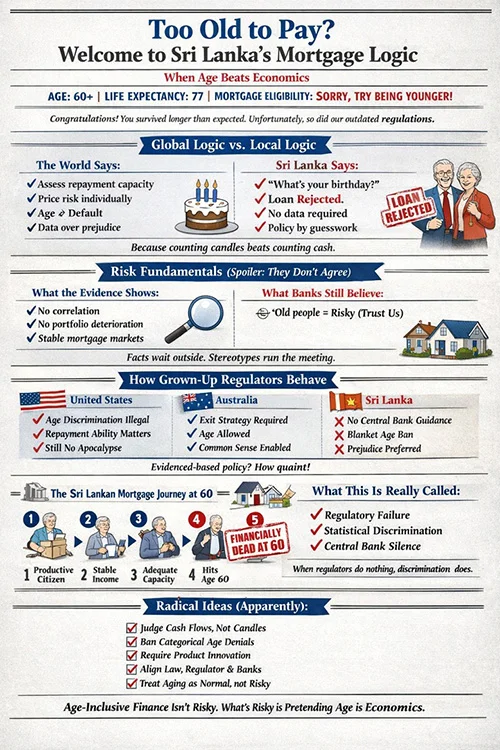

The world welcomes senior home buyers while Sri Lanka shuts the door at 60

Imagine you are 58 years old, financially stable with a decent pension plan, and finally ready to build your dream home in the suburbs of Colombo. You walk into a bank, application in hand, only to be told: “Sorry, your repayment period would extend past 60. We can’t help you”. In Sri Lanka, this scenario plays out daily, leaving thousands of mature, creditworthy citizens locked out of homeownership. But, step outside our shores, you’ll find a drastically different story.

Imagine you are 58 years old, financially stable with a decent pension plan, and finally ready to build your dream home in the suburbs of Colombo. You walk into a bank, application in hand, only to be told: “Sorry, your repayment period would extend past 60. We can’t help you”. In Sri Lanka, this scenario plays out daily, leaving thousands of mature, creditworthy citizens locked out of homeownership. But, step outside our shores, you’ll find a drastically different story.

From the gleaming towers of Singapore to the countryside cottages of the United Kingdom, older borrowers aren’t just tolerated; they’re actively courted by lenders who understand that age doesn’t determine creditworthiness. While Sri Lankan banks remain trapped in outdated policies that effectively discriminate against anyone over 50, the rest of the world has moved on, creating flexible, dignified pathways for seniors to access home loans.

Role of the Central Bank and the Government

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka has failed in its fiduciary duty by not directing financial institutions to refrain from arbitrarily denying home loans, solely on the basis of age. The Ministry of Finance, therefore, the government, is equally responsible for this failure.

This regulatory vacuum enables systematic discrimination against creditworthy older citizens, contradicting modern banking principles and harming an ageing population desperately needing progressive, not punitive, financial policies.

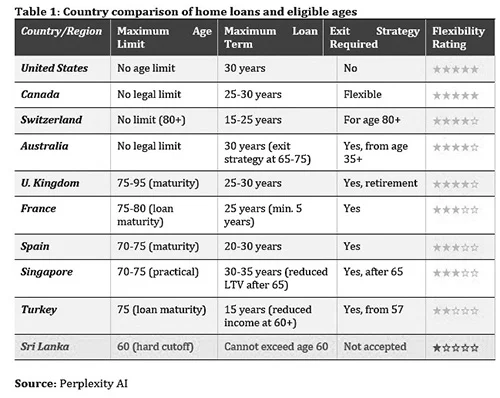

The Global Picture: Where Age is Just a Number

Many advanced economies, such as the United States and Canada, etc., there is no maximum age limit, whatsoever, for obtaining a 30-year mortgage. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act explicitly prohibits age discrimination, meaning an 80-year-old American can walk into a bank and apply for the same three-decade loan term as a 30-year-old, provided they meet income and credit requirements. Lenders evaluate based on current financial stability, not birth certificates. A 65-year-old Canadian with a solid pension can secure a mortgage extending well into their seventies, with the understanding that income, not age, determines repayment capacity.

Australia sets the typical retirement age benchmark at 65-75, and borrowers, over 65, can still obtain mortgages by demonstrating an exit strategy; a credible plan for repayment that might include downsizing, superannuation funds, or ongoing retirement income. The system acknowledges that life doesn’t end at 60, and neither should financial opportunity.

Global Home Loan Conditions:

A Comparative Analysis

The following table ranks countries from most to least affordable for older home loan applicants, based on maximum age limits, flexibility of terms, and accessibility of financing (Table 1).

What Makes These Systems Work?

The countries at the top of our affordability ranking share several key characteristics. First, they recognise that retirement doesn’t mean financial incapacity. Banks in these countries evaluate total financial health, not just employment status.

Second, they embrace the concept of exit strategies, in Australia, for instance, acceptable exit strategies include downsizing property, selling investment assets, or using superannuation (retirement) funds. These strategies are actually considered and evaluated, not dismissed out of hand. Australian lenders assess whether someone’s superannuation balance is sufficient to clear the debt, or if their investment property provides adequate cash flow. It’s a conversation, not a closed door.

Third, many of these countries offer specialised products for older borrowers. The UK, for example, has retirement interest-only mortgages where borrowers pay only interest during their lifetime, with the principal cleared when the property is eventually sold.

Australia provides reverse mortgages for those aged 60 and above. Under this arrangement, the bank pays the homeowner, rather than the homeowner paying the bank, using the house as security. The full outstanding balance is then recovered when the property is eventually sold.

These may not be perfect solutions, but they represent creative thinking about how to serve an ageing population’s housing needs.

The Hidden Cost of Age Discrimination

Sri Lanka’s rigid age-60 cutoff carries consequences that ripple far beyond individual borrowers. In a nation where life expectancy now exceeds 77 years, we’re telling people they are 17 years of ‘too old’ to be trusted ahead of them. This isn’t just unfair; it’s economically counterproductive.

Consider the broader impact. Sri Lanka has one of Asia’s fastest-aging populations. By 2050, one in four Sri Lankans will be over 60. These aren’t economic liabilities; many are professionals with decades of experience, stable incomes, and substantial assets. A 58-year-old doctor with thriving practice and pension security poses less default risk than a 28-year-old in an uncertain job market, yet our banking system treats them as if the opposite were true.

Learning from Singapore: A Regional

Success Story

We don’t need to look to distant Western nations for alternatives. Singapore, our regional neighbour facing similar demographic challenges, has crafted a more balanced approach. While Singapore’s Monetary Authority hasn’t imposed a hard age limit, banks do apply careful scrutiny to loans extending past age 65.

A Singaporean borrower, over 65, can still obtain financing, but with reduced loan-to-value ratios. If you’re buying a property worth one million dollars and you’re under 65, you might borrow up to 75 percent. Over 65, that drops to 60 percent. It’s more conservative, certainly, but it preserves opportunity.

This approach acknowledges risk without eliminating possibility. It says to older borrowers: Yes, we’ll lend it to you, but we need you to have more equity in the game. Compare this to Sri Lanka’s approach, which effectively says: “We don’t care how much equity you have or how stable your income is, you’re too old”.

A Path Forward for Sri Lanka

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka could issue guidelines similar to Singapore’s loan-to-value adjustments. For borrowers whose loan terms extend past 65, reduce the maximum LTV from 90 percent to 70 or 75 percent.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka could issue guidelines similar to Singapore’s loan-to-value adjustments. For borrowers whose loan terms extend past 65, reduce the maximum LTV from 90 percent to 70 or 75 percent.

This protects banks from excessive risk while allowing creditworthy older borrowers to access financing. It’s a middle ground that respects both prudent lending standards and individual dignity.

Additionally, Sri Lanka could develop specialised products for its ageing population. Retirement interest-only loans, similar to those in the UK, could serve retirees who have substantial home equity but limited monthly income. Reverse mortgages, properly regulated with strong consumer protections, could help elderly Sri Lankans tap into home equity without monthly payments.

Beyond Banking: A Cultural Shift

Ultimately, changing Sri Lanka’s approach to older borrowers requires more than policy adjustments; it demands a cultural reckoning with how we value our ageing citizens. The countries that lead in age-friendly lending, the United States, Canada, Australia, share a broader commitment to recognising that people can remain economically active and financially responsible well into their later years.

These nations have moved beyond viewing retirement as an endpoint and recognised it as a transition. A 65-year-old today might have 20 or more active years ahead, years in which they’ll continue working part-time, managing investments, drawing stable pensions, and yes, making mortgage payments. Our banking sector needs to catch up to this reality.

Conclusion: Time for Change

As our table demonstrates, Sri Lanka stands alone at the bottom of the global ranking for age-friendly home lending. We’re more restrictive than Turkey with its 15-year maximum terms, more inflexible than Singapore with its sliding loan-to-value scales, and incomparably more rigid than the United States, Canada, or Switzerland, where age barely factors into lending decisions at all.

This isn’t about being soft on risk or abandoning prudent lending standards. Countries with no age limits still assess income, evaluate debt-to-income ratios, and verify creditworthiness. They simply don’t use age as a crude proxy for financial competence. The initiative lies with the Ministry of Finance, which must direct the Central Bank accordingly.

For Sri Lanka’s 58-year-old aspiring homeowner, the current system isn’t just frustrating; it’s a form of systematic discrimination that would be illegal in most developed economies. As our population ages and life expectancy increases, maintaining this policy becomes increasingly untenable. The question isn’t whether Sri Lankan banks will change their approach to older borrowers, but when and how many dreams will be deferred or destroyed in the meantime.

The world has shown us better ways forward. It’s time Sri Lanka joined the 21st century in recognising that 60 isn’t the end of financial opportunity for many, it’s just the beginning.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Securing public trust in public office: A Christian perspective – Part II

This is an adapted version of the Bishop Cyril Abeynaike Memorial Lecture delivered on 14 June 2025 at the invitation of the Cathedral Institute for Education and Formation, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

(Continued from yesterday)

The public are entitled to expect their public servants to be intrinsically committed to the truth. From a consequentialist perspective, to secure public trust, public office must be oriented towards justice. Public officers ought to lend their mind to responding to the injustices that they can address within their mandate. This is precisely what Lalith Ambanwela did. His job was to audit the accounts, which he did truthfully and thereby revealed injustices. If he had paused to worry about the risks involved or if he had wondered whether he could have rid the entire system of corruption, the obvious answer to that would have stopped him from taking any truthful action. Rather, he responded to the injustice that he saw, in a truthful manner, thereby improving the trust the public could have in his office.

Notwithstanding the Ambanwela example, one may still ask, in a place like Sri Lanka, what is the point in a single public official being truthful in a context where the problems are institutional, systemic, generational and entrenched – such as corruption or abuse of power? Many of us are familiar with the line of reasoning which suggests that there is no point in being truthful as a single individual, at any level of public service- there will be no impact except for trouble and stress; that one person cannot change systems; that one must wait for a more suitable time; that one must be strategic; that one must think of one’s children safety and future; and that one must be cautious and not attract trouble. Women, in particular, are told – do not be difficult or extreme, just let this go because you cannot change the world.

This is where we come back to the intrinsic justification for truthfulness and a Christian perspective helps us understand the need to cultivate such an intrinsic motivation. The commitment to truthfulness, the Christian faith suggests, is not subject to whether the consequences are palatable or not, as to whether you may be successful or not, but rather, regardless of those consequences. But to sustain such a commitment to truthfulness, I think we need a nurturing environment – a point which I do not have time to speak to today.

Before moving to the second attribute, which is rationality, I want to mention a few other points that I will not be dealing with today. We need to acknowledge that there can be different approaches to discovering the truth and there can be, at least in some instances, different truths. This is reflected in the fact that we have four Gospels that account for the life and ministry of Jesus, reminding us that pursuing the truth has its own in-built challenges. Furthermore, truth is inter-dependent with many other attributes, including trust and freedom.

·

1. Rationality

I now turn to rationality, the second attribute that I think is necessary for securing public trust in public office. In public law, which is the area of law that I specialise in, rationality is a core value and a foundational principle. In contrast, it is fair to say that religion is commonly understood as requiring a faith-based approach – often considered to be the anti-thesis of rationality. However, the creation account in the Bible suggests to us that we were created in the image of God and that at least one of the attributes of human nature is rationality. Furthermore, it has been argued that even Science, generally considered to be a discipline based on rationality and objectivity, is also ultimately based on assumptions and therefore on belief. A previous lecture in this lecture series, by Prof Priyan Dias, explored these ideas in detail.

In my study of public law and in my own experiences in exercising public power, I have observed, of myself and of others like me, that cultivating rationality and maintaining a commitment to it, is a challenge. The need for rationality arises when we are given discretion. Academics, for instance, are given discretion in grading student exams or when supervising doctoral students. Members of the judiciary exercise significant discretion in hearing cases. In Sri Lanka’s Constitutional Council, the members have discretion to approve or disapprove the nominations made by the President to constitutional high office including to the office of the Chief Justice and Inspector General of Police. As I mentioned earlier, where there is discretion, the law requires the person exercising that discretion to be rational.

How should public officials practice rationality? In my view, there are five aspects to practicing rationality in decision-making. First, public officials ought to be able to think objectively about each decision they are required to make. Second, to think objectively, we have to be able to identify the purpose for which discretionary power has been given to us. Third, where necessary, we ought to consult others and/or seek advice and fourth, we have to be able to resist any pressure that might be cast on us, to be biased. Fifth, we should have reasons for our decision and consider it our duty to state those reasons to the world at large.

Let me say a bit more about these five aspects. When, as public officials, we exercise discretionary power, we ought to cultivate the habit of separating the personal from the professional. In public law we say that we should adopt the perspective of a fair minded and reasonable observer. But we know that our own situations often shape even our very idea of objectivity. For example, if a decision-making body comprises only men, or if a public institution has been only headed by men or has very few women at decision-making levels, objectivity could very well lead to decision-making that does not take account of the different issues that women face. All this to say, that objectivity is not simply the absence of personal bias but a way of making decisions where a public official is committed to taking account of all relevant perspectives and thinking rationally about them. No easy task, but that, I think, is what is required of public officials who seek to secure public trust.

The second aspect to rationality is having an appreciation and commitment to the purpose for which discretion has been vested in us. To do so, as public officials, whether we like it or not, we need to have some appreciation for the legal or policy basis on which discretionary power has been vested in us. You may think that this makes the job easier for lawyers. Well, I can tell you that it has not been uncommon for me to be in decision-making situations where even lawyers do not know or have not done their homework to understand what the law requires of us. Recall here the second example I cited, that of Thulsi Madonsela, the former Public Protector of South Africa. She was very clear about the purpose of her office – to ensure accountability. The rationality of her reports on the excessive spending on the President’s house and the report on state capture, have withstood the test of time and spoken truth to power, rationally.

Permit me to make a further point here. The law itself can, and, sometimes is, unjust or unclear. In such contexts, what is the role of a public official? In Sri Lanka, only the Parliament can change laws. Those who hold public office and who derive power from a specific law can only implement it. But and this is very significant, almost always, public officials are required to interpret the law in order to understand its purpose, scope etc. For instance, in Sri Lanka, the law does not lay down the minimum qualifications for several key constitutional offices. The nomination of persons to these offices is through a process of convention, that is to say practice. In my view, this is far from desirable. However, while the law remains this way, the President has the discretion to nominate persons to these constitutional offices and the Constitutional Council is required to approve or disapprove such nominations. The lack of clarity in the relevant constitutional provisions casts a heavy duty on both the President and the Constitutional Council to ensure that they all exercise the discretion vested in them, for the purpose for which such discretion has been given. To do so, both the President and the Council ought to have an appreciation for each of these constitutional high offices, such as that of the Attorney-General or Auditor General and exercise their discretion rationally for the benefit of the people.

Consulting relevant parties and obtaining advice is the third aspect of rationality that I identified. It is not unusual for public officials to consult or obtain advice. Complex decisions are often best made with feedback from suitably qualified and experienced persons. who will share their independent opinion with you and where necessary, disagree with you. However, what I have observed in my work so far is the following. Public officials who seek advice, often select other public officials or experts who they like, or ones with whom they have a transactional relationship or ones who may not think differently from them. Correspondingly, the advice givers, often public officials themselves, seek to agree and please (or even appease) rather than give independent, subject based rational advice. This type of advice subverts the purpose of the law, bends it to political will and is disingenuous. I am sure, we can all think of examples from Sri Lanka where this has happened, sometimes even causing tragic loss of life or irreversible harm to human dignity.

Permit me to give you a personal example which is now etched in my mind. In November, 2023, the then President proposed to the Parliament that due to the non-approval of a nomination he had made to judicial office, that a Parliamentary Select Committee should be appointed to inquire into the Constitutional Council (The Sunday Times 26 November 2023). Feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of being hauled before a Parliamentary Select Committee while also recalling experiences of some public officials before such proceedings, the day after this announcement was made, I sat at my desk and typed out my letter of resignation (Daily Mirror 23 November 2023). I then rang up one of my lawyers to discuss this. I told him that I am resigning as I could not take what was to come. He responded very gently and made two points: 1) that I ought to not resign and need to see this through, whatever the process might entail and 2) that he and others will stand by me every step of the way. As you can imagine, that was not what I wanted to hear and it distressed me even more. Today, I recall that conversation with much humility and appreciation. That advice was certainly not what I wanted to hear that night but most certainly what I needed to hear.

The fourth aspect of rationality is resisting pressure which I will address later.

I will only speak briefly on the fifth aspect of rationality – that of having and stating reasons for decisions. In my view, if a public official is not able to provide reasons for a decision, it is a good indication of the need to rethink that decision. The external dimension of this aspect is one we all know. When a public official exercises public power, they are obliged to explain the reasons for their decisions. This is essential for securing the trust of the people and they owe it to us because they exercise public power, on our behalf. It goes without saying that public officials and the public should know the difference between rational reasons and reasons which are disingenuous – reasons which seek to hide rather than reveal.

So, to sum up on the points I made about rationality, I highlighted five features of this attribute, being objective in decision-making, being limited and guided by the purpose for which discretionary power has been given, consulting and/or seeking honest and expert-based advice, resisting any pressure to be biased and recording reasons for decisions. (To be continued)

by Dinesha Samararatne

Professor, Dept of Public & International Law, Faculty of Law, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka and independent member, Constitutional Council of Sri Lanka (January 2023 to January 2026)

Features

From disaster relief to system change

The impact of Cyclone Ditwah was asymmetric. The rains and floods affected the central hills more severely than other parts of the country. The rebuilding process is now proceeding likewise in an asymmetric manner in which the Malaiyaha Tamil community is being disadvantaged. Disasters may be triggered by nature, but their effects are shaped by politics, history and long-standing exclusions. The Malaiyaha Tamils who live and work on plantations entered this crisis already disadvantaged. Cyclone Ditwah has exposed the central problem that has been with this community for generations.

A fundamental principle of justice and fair play is to recognise that those who are situated differently need to be treated differently. Equal treatment may yield inequitable outcomes to those who are unequal. This is not a radical idea. It is a core principle of good governance, reflected in constitutional guarantees of equality and in international standards on non-discrimination and social justice. The government itself made this point very powerfully when it provided a subsidy of Rs 200 a day to plantation workers out of the government budget to do justice to workers who had been unable to get the increase they demanded from plantation companies for nearly ten years. The same logic applies with even greater force in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah.

A discussion last week hosted by the Centre for Policy Alternatives on relief and rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah brought into sharp focus the major deprivation continually suffered by the Malaiyaha Tamils who are plantation workers. As descendants of indentured labourers brought from India by British colonial rulers over two centuries ago, plantation workers have been tied to plantations under dreadful conditions. Independence changed flags and constitutions, but it did not fundamentally change this relationship. The housing of plantation workers has not been significantly upgraded by either the government or plantation companies. Many families live in line rooms that were not designed for permanent habitation, let alone to withstand extreme weather events.

Unimplementable Promise

In the aftermath of the cyclone disaster, the government pledged to provide every family with relief measures, starting with Rs 25,000 to clean their houses and going up to Rs 5 million to rebuild them. Unfortunately, a large number of the affected Malaiyaha Tamil people have not received even the initial Rs 25,000. Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers do not own the land on which they live or the houses they occupy. As a result, they are not eligible to receive the relief offered by the government to which other victims of the cyclone disaster are entitled. This is where a historical injustice turns into a present-day policy failure. What is presented as non-partisan governance can end up reproducing discrimination.

The problem extends beyond housing. Equal rules applied to unequal conditions yield unequal outcomes. Plantation workers cannot register their small businesses because the land on which they conduct their businesses is owned by plantation companies. As their businesses are not registered, they are not eligible for government compensation for loss of business. In addition, government communication largely takes place in the Sinhala language. Many families have no clear idea of the processes to be followed, the documents required or the timelines involved. Information asymmetry deepens powerlessness. It is in this context that Malaiyaha Tamil politicians express their feeling that what is happening is racism. The fact is that a community that contributes enormously to the national economy remains excluded from the benefits of citizenship.

What makes this exclusion particularly unjust is that it is entirely unnecessary. There is anything between 200,000-240,000 hectares available to plantation companies. If each Malaiyaha Tamil family is given ten perches, this would amount to approximately one and a half million perches for an estimated one hundred and fifty thousand families. This works out to about four thousand hectares only, or roughly two percent of available plantation land. By way of contrast, Sinhala villages that need to be relocated are promised twenty perches per family. So far, the Malaiyaha Tamils have been promised nothing.

Adequate Land

At the CPA discussion, it was pointed out that there is adequate land on plantations that can be allocated to the Malaiyaha Tamil community. In the recent past, plantation land has been allocated for different economic purposes, including tourism, renewable energy and other commercial ventures. Official assessments presented to Parliament have acknowledged that substantial areas of plantation land remain underutilised or unproductive, particularly in the tea sector where ageing bushes, labour shortages and declining profitability have constrained effective land use. The argument that there is no land is therefore unconvincing. The real issue is not availability but political will and policy clarity.

Granting land rights to plantation communities needs also to be done in a systematic manner, with proper planning and consultation, and with care taken to ensure that the economic viability of the plantation economy is not undermined. There is also a need to explain to the larger Sri Lankan community the special circumstances under which the Malaiyaha Tamils became one of the country’s poorest communities. But these are matters of design, not excuses for inaction. The plantation sector has already adapted to major changes in ownership, labour patterns and land use. A carefully structured programme of land allocation for housing would strengthen rather than weaken long term stability.

Out of one million Malaiyaha Tamils, it is estimated that only 100,000 to 150,000 of them currently work on plantations. This alone should challenge outdated assumptions that land rights for plantation communities would undermine the plantation economy. What has not changed is the legal and social framework that keeps workers landless and dependent. The destruction of housing is now so great that plantation companies are unlikely to rebuild. They claim to be losing money. In the past, they have largely sought to extract value from estates rather than invest in long term community development. This leaves the government with a clear responsibility. Disaster recovery cannot be outsourced to entities that disclaim responsibility when it becomes inconvenient in dealing with citizens of the country with the vote.

The NPP government was elected on a promise of system change. The principle of equal treatment demands that Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers be vested with ownership of land for housing. Justice demands that this be done soon. In a context where many government programmes provide land to landless citizens across the country, providing land ownership to Malaiyaha Tamil families is good governance. Land ownership would allow plantation workers to register homes, businesses and cooperatives and would enable them to access credit, insurance and compensation which are rights of citizens guaranteed by the constitution. Most importantly, it would give them a stake that is not dependent on the goodwill of companies or the discretion of officials. The question now is whether the government will use this moment to rebuild houses and also a common citizenship that does not rupture again.

by Jehan Perera

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days ago‘Building Blocks’ of early childhood education: Some reflections